Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Diabetes has been shown to be associated with worse survival and repeat target vessel revascularization (TVR) after primary angioplasty. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the impact of diabetes on long-term outcome in patients undergoing primary angioplasty treated with bare metal stents (BMS) and drug-eluting stents (DES).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Our population is represented by 6,298 ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients undergoing primary angioplasty included in the DESERT database from 11 randomized trials comparing DES with BMS.

RESULTS

Diabetes was observed in 972 patients (15.4%) who were older (P < 0.001), more likely to be female (P < 0.001), with higher prevalence of hypertension (P < 0.001), hypercholesterolemia (P < 0.001), and longer ischemia time (P < 0.001), and without any difference in angiographic and procedural characteristics. At long-term follow-up (1,201 ± 441 days), diabetes was associated with higher rates of death (19.1% vs. 7.4%; P < 0.0001), reinfarction (10.4% vs. 7.5%; P < 0.001), stent thrombosis (7.6% vs. 4.8%; P = 0.002) with similar temporal distribution—acute, subacute, late, and very late—between diabetic and control patients, and TVR (18.6% vs. 15.1%; P = 0.006). These results were confirmed in patients receiving BMS or DES, except for TVR, there being no difference observed between diabetic and nondiabetic patients treated with DES. The impact of diabetes on outcome was confirmed after correction for baseline confounding factors (mortality, P < 0.001; repeat myocardial infarction, P = 0.006; stent thrombosis, P = 0.007; TVR, P = 0.027).

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that among STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty, diabetes is associated with worse long-term mortality, reinfarction, and stent thrombosis in patients receiving DES and BMS. DES implantation, however, does mitigate the known deleterious effect of diabetes on TVR after BMS.

Primary angioplasty currently represents the best reperfusion therapy for the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (1–2). Further improvement has been obtained by optimization of antithrombotic therapies and adjunctive mechanical devices (3–5). Special attention has been given in the last years to diabetes, because it has been associated with higher rates of impaired reperfusion, mortality, and target vessel revascularization (TVR) after primary angioplasty (6–8). In fact, even though bare metal stents implantation (BMS) has reduced the occurrence of restenosis as compared with balloon angioplasty in selected STEMI patients (9,10), the results seem to be worse in unselected populations (11,12), especially among diabetic patients (13–15). Drug-eluting stents (DES) have been shown in several randomized trials to reduce restenosis and TVR in both elective (16,17) or STEMI patients (18,19) compared with BMS. However, concerns have emerged on the potential higher risk of stent thrombosis and death with DES (20,21), which might be even more pronounced among STEMI patients (22,23). Few data have been reported on the impact of diabetes on long-term outcome with both BMS and DES in STEMI; therefore, that was the aim of the current study.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Our population is represented by STEMI patients included in the DESERT cooperation. Detailed data have been previously described (19). Briefly, we collected data from 11 randomized trials on DES in STEMI, including baseline characteristics (age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, previous revascularization, infarct location, ischemia time) and major angiographic variables (preprocedural thrombolysis in myocardial infarction [TIMI] flow, infarct-related artery, postprocedural TIMI flow, use of Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors), and complete follow-up data, such as mortality, reinfarction, TVR, and stent thrombosis (defined according to Academic Research Consortium definite or probable definition). A temporal analysis was performed for stent thrombosis events that were divided into four groups: acute (within 24 h); subacute (between 24 h and 30 days); late (between 1 and 12 months); and very late (later than 12 months of follow-up).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 15.0 statistical package. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD and categorical data as percentage. The ANOVA was appropriately used for continuous variables. The χ2 test or the Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. The differences in event rates between groups during the follow-up period were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier method using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards method analysis was used to calculate relative risks adjusted for differences in baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics that were all entered in block.

RESULTS

Patient population

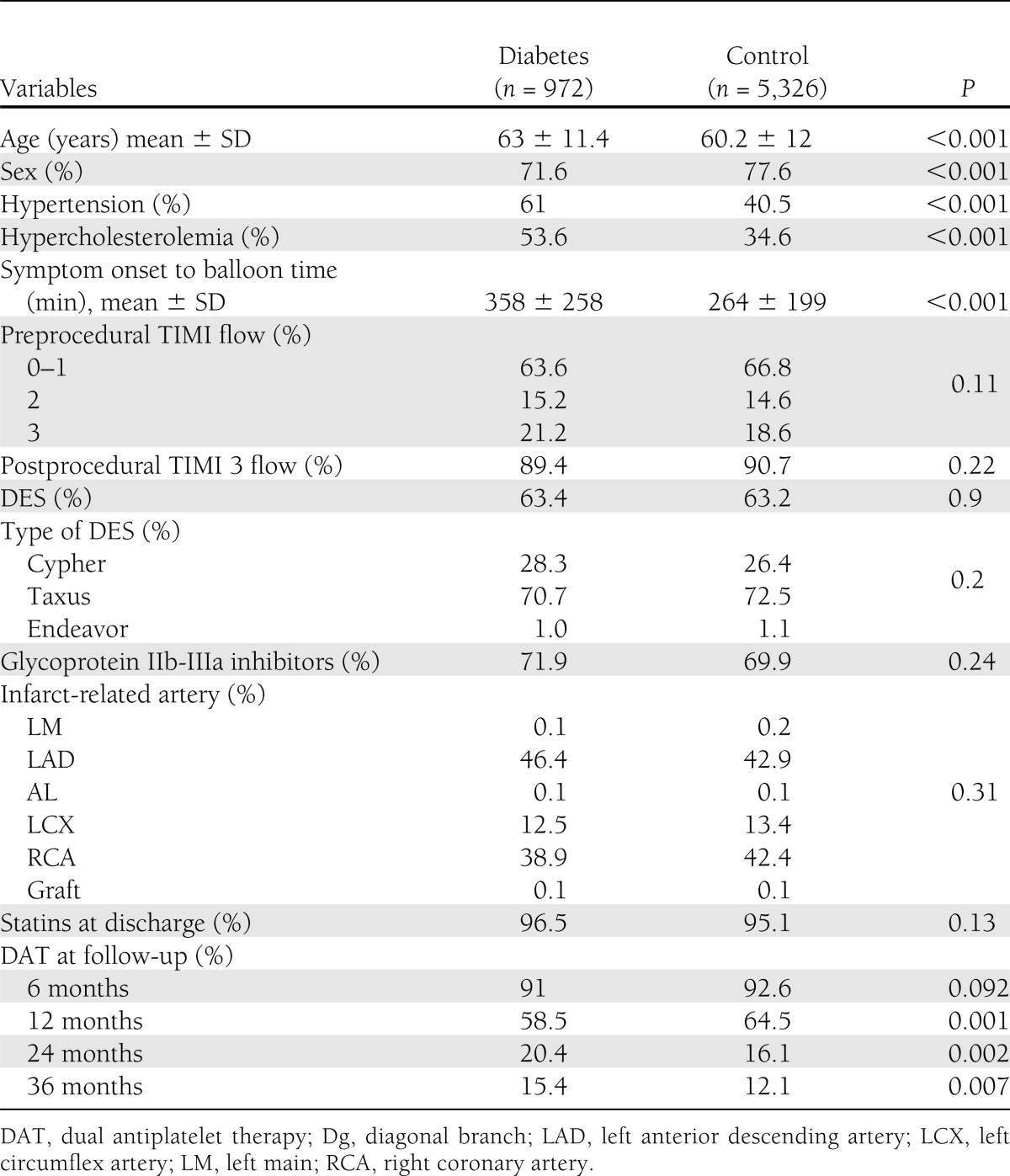

Our population is represented by 6,298 STEMI patients. Diabetes was observed in 972 (15.4%) patients. As shown in Table 1, patients with diabetes were older (63 ± 11.4 vs. 60.2 ± 12 years; P < 0.001), more likely to be female (71.6% vs. 77.6%; P < 0.001), and more likely to have hypertension (61% vs. 40.5%; P < 0.001), hypercholesterolemia (53.6% vs. 34.6%; P < 0.001), and longer ischemia time (358 ± 258 vs. 264 ± 199 min; P < 0.001). No difference was observed in terms of angiographic and procedural characteristics. Almost 50% of patients underwent PCI of left anterior descending artery. Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors were equally administrated in both groups (71.9% vs. 69.9%), as much as statin therapy at discharge (96.5% vs. 95.1%). As reported in Table 1, diabetic patients were less often using clopidogrel at follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to diabetes

Diabetes and long-term outcome

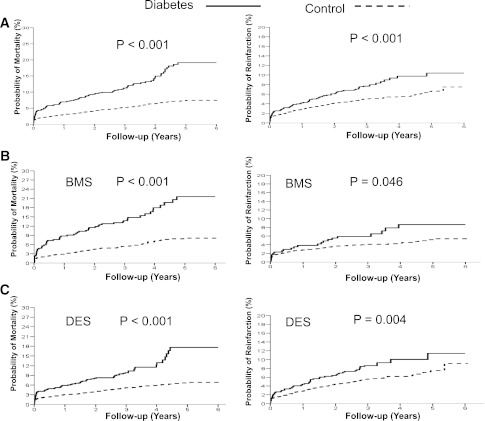

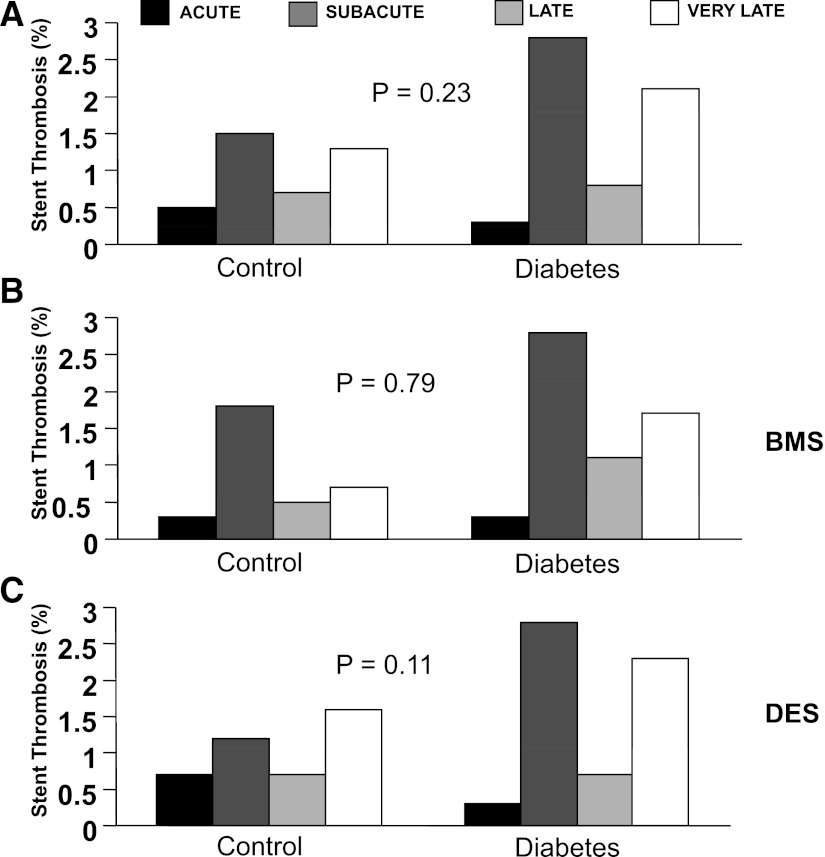

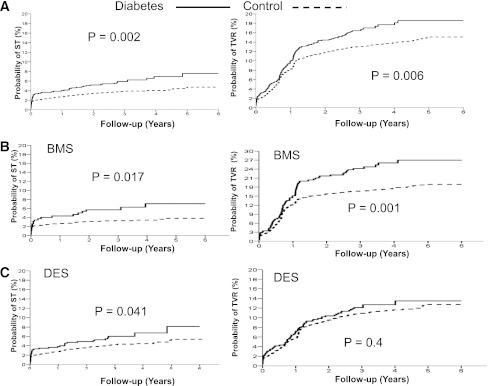

Follow-up data were available at a mean of 1,201 ± 441 days. At long-term follow-up, diabetes was associated with a significantly higher rate of death (19.1% vs. 7.4%; hazard ratio [HR] 2.38 [95% CI 1.97–2.93]; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1) and reinfarction (10.4% vs. 7.5%; HR 1.58 [1.23–2.04]; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1), stent thrombosis (7.6% vs. 4.8%; 1.573 [1.17–2.11]; P = 0.002) (Fig. 2), with similar temporal distribution (acute, subacute, late, and very late) between diabetic and control patients (Fig. 3) and TVR (18.6% vs. 15.1%; 1.28 [1.07–1.52]; P = 0.006) (Fig. 2). These results were confirmed in patients receiving BMS or DES, except for TVR, in which no difference was observed between diabetic and nondiabetic patients treated with DES (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the impact of diabetes on survival (left graphs) and reinfarction (right graphs) in the overall population (A), in patients with BMS (B), and in patients with DES (C).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the impact of diabetes on event-free survival from stent thrombosis (ST; left graphs) and TVR (right graphs) in the overall population (A), in patients with BMS (B), and in patients with DES (C).

Figure 3.

Bar graphs show time distribution of stent thrombosis in overall population. BMS Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the impact of diabetes on event-free survival from stent thrombosis in overall population (A), in patients with BMS (B), and in patients with DES (C).

The impact of diabetes on outcome was confirmed after correction for baseline confounding factors (age, gender, hypertension hypercholesterolemia, ischemia time) (mortality: HR 1.76 [95% CI 1.35–2.29]; P < 0.001; reinfarction: 1.48 [1.12–1.97]; P = 0.006; stent thrombosis: 1.5 [1.12–2.02]; P = 0.007; TVR: 1.22 [1.02–1.46]; P = 0.027).

CONCLUSIONS

The main finding of the current study was that diabetes was associated with a significantly higher mortality, reinfarction, TVR, and stent thrombosis. These results were similarly observed among patients treated with BMS or DES, except for TVR, in which no difference was observed among patients treated with DES.

Several studies have demonstrated that hyperglycemia at admission, even independently from the presence of diabetes (stress hyperglycemia), is associated with larger infarct size and higher mortality in patients with STEMI (24–28). In fact, several in vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that hyperglycemia may be involved in the reperfusion injury (29–34). Acute hyperglycemia increases intercellular adhesion molecule-1 levels (29), which could augment plugging of leukocytes in the capillaries (30). Hyperglycemia also may augment thrombus formation. Blood glucose has been demonstrated to be an independent predictor of platelet-dependent thrombosis, even in the normal range (31). A recent study suggested that a microthrombus in the capillaries play a crucial role in the no-reflow phenomenon after STEMI (32).

In a recent report, De Luca et al. (7) found that among patients treated with glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors, diabetes was associated with higher occurrences of distal embolization and impaired myocardial reperfusion and higher mortality.

However, diabetes is associated with a significantly higher rates of restenosis (13,14). In a previous report, De Luca et al. (35) found that BMS did not provide significant benefits in outcome as compared with balloon angioplasty in unselected diabetic patients undergoing primary angioplasty. The recent introduction of DES certainly has reduced the risk of restenosis, which may be counterbalanced by a higher rate of late in-stent thrombosis, especially among STEMI. Few data have been reported regarding diabetic patients with STEMI in the era of DES. A recent individual patient data meta-analysis showed that among STEMI diabetic patients undergoing primary angioplasty, the use of DES was safe and associated with a significant reduction in TVR at 1-year follow-up. However, a late catch-up phenomenon in terms of restenosis has been described with a potential risk of late in-stent thrombosis. A subanalysis of the PASEO trial showed that at 5-year follow-up, diabetes was associated with a significantly worse outcome with both DES and BMS (36,37). However, diabetes did not affect the long-term occurrence of TVR among patients treated with DES.

This is first large report on the impact of diabetes on long-term outcome of STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty with BMS or DES. We found that diabetes was associated with significantly higher mortality, reinfarction, and in-stent thrombosis, irrespective of DES or BMS. However, although diabetes was associated with a significantly higher rate of TVR among patients treated with DES, it did increase TVR among patients treated with DES. A similar temporal distribution was observed in terms of stent thrombosis between diabetic and control patients with both BMS and DES.

Limitations

Our patients were enrolled in randomized trials, and few patients had cardiogenic shock. Thus, the conclusion of this meta-analysis cannot be extended to all patients undergoing primary PCI for STEMI. The results of the current analysis apply only to sirolimus-eluting stent and paclitaxel-eluting stent because substantial randomized studies in STEMI have not yet been performed with newer DES. Admission glucose and HbA1c levels that have been shown as major determinants of outcome in STEMI patients were not routinely collected. Data regarding the duration of diabetes and the therapeutic regimen were not available, and the type of diabetes was not uniformly defined among studies (IDDM/NIDDM in some or any insulin-requiring diabetes in some others). Therefore, the prognostic impact of such variables could not be analyzed. Finally, the levels of LDL, triglyceride, and BMI were not collected in our database. Their availability certainly would have improved our results.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that among STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty, diabetes is associated with worse long-term mortality, reinfarction, and in-stent thrombosis, even with DES implantation, which was able to overcome the known deleterious effect of diabetes on TVR. Diabetes did not impact on the temporal distribution of stent thrombosis events with BMS and DES.

Acknowledgments

M.S. received research grants from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Biotronik. C.K. is on the advisory board at Ely Lilly and received research/travel support from Abbott Vascular. G.W.S. is a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

G.D.L. and G.W.S. conceived and designed the study. G.D.L. performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. G.D.L., M.T.D., C.S., H.K., M.S., L.T., B.v.d.H., M.A.V., C.K., C.M., T.C., G.S., L.S.D.d.l.L., V.P., E.D.L., R.V., H.S., and G.W.S. interpreted data. M.T.D., C.S., H.K., M.S., L.T., B.v.d.H., M.A.V., C.K., C.M., T.C., G.S., L.S.D.d.l.L., V.P., E.D.L., R.V., H.S., and G.W.S. performed critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content of the article. G.D.L. had full access to the data and takes full responsibility for this work as a whole, including the study design and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

References

- 1.De Luca G, Cassetti E, Marino P. Percutaneous coronary intervention-related time delay, patient’s risk profile, and survival benefits of primary angioplasty vs lytic therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med 2009;27:712–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Luca G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Marino P. Transferring patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction for mechanical reperfusion: a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52:665–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Luca G, Cassetti E, Verdoia M, Marino P. Bivalirudin as compared to unfractionated heparin among patients undergoing coronary angioplasty: A meta-analyis of randomised trials. Thromb Haemost 2009;102:428–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Luca G, Navarese E, Marino P. Risk profile and benefits from Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty: a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2009;30:2705–2713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Luca G, Navarese EP, Suryapranata H. A meta-analytic overview of thrombectomy during primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 2012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Luca G, Małek LA, Maciejewski P, et al. STEMI 2003 Registry Collaborators Impact of diabetes on survival in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty: insights from the POLISH STEMI registry. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:516–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Luca G, Gibson CM, Bellandi F, et al. Diabetes mellitus is associated with distal embolization, impaired myocardial perfusion, and higher mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty and glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors. Atherosclerosis 2009;207:181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmer JR, van der Horst IC, de Luca G, et al. Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group Comparison of myocardial perfusion after successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction with versus without diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:1375–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone GW, Grines CL, Cox DA, et al. Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Investigators Comparison of angioplasty with stenting, with or without abciximab, in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2002;346:957–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Stone GW, et al. Coronary stenting versus balloon angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Int J Cardiol 2008;126:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antoniucci D, Migliorini A, Parodi G, et al. Abciximab-supported infarct artery stent implantation for acute myocardial infarction and long-term survival: a prospective, multicenter, randomized trial comparing infarct artery stenting plus abciximab with stenting alone. Circulation 2004;109:1704–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suryapranata H, De Luca G, van ’t Hof AW, et al. Is routine stenting for acute myocardial infarction superior to balloon angioplasty? A randomised comparison in a large cohort of unselected patients. Heart 2005;91:641–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elezi S, Kastrati A, Pache J, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the clinical and angiographic outcome after coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:1866–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolognese L, Carrabba N, Santoro GM, Valenti R, Buonamici P, Antoniucci D. Angiographic findings, time course of regional and global left ventricular function, and clinical outcome in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:544–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, et al. SIRIUS Investigators Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1315–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, et al. TAXUS-IV Investigators A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:221–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spaulding C, Henry P, Teiger E, et al. TYPHOON Investigators Sirolimus-eluting versus uncoated stents in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1093–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Lorenzo E, De Luca G, Sauro R, et al. The PASEO (PaclitAxel or Sirolimus-Eluting Stent Versus Bare Metal Stent in Primary Angioplasty) Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009;2:515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Luca G, Dirksen MT, Spaulding C, et al. Drug-Eluting Stent in Primary Angioplasty (DESERT) Cooperation Drug-eluting vs bare-metal stents in primary angioplasty: a pooled patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:611–621; discussion 621–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2005;293:2126–2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagerqvist B, James SK, Stenestrand U, Lindbäck J, Nilsson T, Wallentin L, SCAAR Study Group Long-term outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in Sweden. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1009–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kernis SJ, Cohen D, Rein K. Clinical outcome associated with use of drug-eluting stents compared with bare metal stent for primary percutaneous intervention. Am J Cardiol 2005;96(Suppl. 7A):47H [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent placement: results from the PREMIER registry. Circulation 2006;113:2803–2809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 2000;355:773–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolk J, van der Ploeg T, Cornel JH, Arnold AE, Sepers J, Umans VA. Impaired glucose metabolism predicts mortality after a myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2001;79:207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter A, Assali AR, Zahalka A, et al. Impaired fasting glucose and outcomes of ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome treated with primary percutaneous intervention among patients without previously known diabetes mellitus. Am Heart J 2008;155:284–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marso SP, Miller T, Rutherford BD, et al. Comparison of myocardial reperfusion in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction with versus without diabetes mellitus (from the EMERALD Trial). Am J Cardiol 2007;100:206–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishihara M, Kagawa E, Inoue I, et al. Impact of admission hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus on short- and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction in the coronary intervention era. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1674–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marfella R, Esposito K, Giunta R, et al. Circulating adhesion molecules in humans: role of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Circulation 2000;101:2247–2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Booth G, Stalker TJ, Lefer AM, Scalia R. Elevated ambient glucose induces acute inflammatory events in the microvasculature: effects of insulin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001;280:E848–E856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shechter M, Merz CN, Paul-Labrador MJ, Kaul S. Blood glucose and platelet-dependent thrombosis in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakuma T, Leong-Poi H, Fisher NG, Goodman NC, Kaul S. Further insights into the no-reflow phenomenon after primary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction: the role of microthromboemboli. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nitenberg A, Valensi P, Sachs R, Dali M, Aptecar E, Attali JR. Impairment of coronary vascular reserve and ACh-induced coronary vasodilation in diabetic patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries and normal left ventricular systolic function. Diabetes 1993;42:1017–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishihara M, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Diabetes mellitus prevents ischemic preconditioning in patients with a first acute anterior wall myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1007–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Timmer J, et al. Impact of routine stenting on clinical outcome in diabetic patients undergoing primary angioplasty for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care 2006;29:920–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Lorenzo E, Sauro R, Varricchio A, et al. Benefits of drug-eluting stents as compared to bare metal stent in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: four year results of the PaclitAxel or Sirolimus-Eluting stent vs bare metal stent in primary angiOplasty (PASEO) randomized trial. Am Heart J 2009;158:e43–e50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Luca G, Sauro R, Varricchio A, et al. Impact of diabetes on long-term outcome in STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty with glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors and BMS or DES. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2010;30:133–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]