Abstract

Background

Obese individuals with binge eating disorder (BED) frequently experience impairments in mood and quality of life which improve with surgical or behavioral weight loss interventions. It is unclear if these improvements are due to weight loss itself, or to additional aspects of treatment such as group support, or acquisition of cognitive-behavioral skills provided in behavioral interventions.

Objectives

To compare changes in weight, symptoms of depression, and quality of life, in extremely obese individuals with BED undergoing bariatric surgery or a lifestyle modification intervention.

Setting

University Hospital

Methods

Symptoms of depression and quality of life were assessed at baseline and 2, 6, and 12 months in participants undergoing bariatric surgery but no lifestyle intervention (n=36) and non-surgery participants receiving a comprehensive program of lifestyle modification (n=49).

Results

Surgery participants lost significantly more weight than lifestyle participants at 2, 6 and 12 months (p’s<0.001). Significant improvements in both mood (as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory-II) and quality of life (as measured by the Short Form-36) were observed in both groups across the year, but there were no differences between the groups at month 12 (even when controlling for reductions in binge eating). A positive correlation was observed between the magnitude of weight loss and change in BDI-II score when collapsing across groups. Moreover, weight loss at one time point predicted BDI-II score at the next time point, but BDI-II score did not predict subsequent weight loss.

Conclusions

We conclude that similar improvements in mood and quality of life can be expected from either bariatric surgery or lifestyle modification treatments for periods up to 1 year.

Keywords: depression, obesity, bariatric surgery, lifestyle modification, quality of life, binge-eating

Introduction

Symptoms of depression and impaired quality of life are common in obese individuals who have binge eating disorder (BED). (1–3) BED is characterized by the consumption of an objectively large amount of food in a small period of time (2 hours or less), accompanied by a sense of loss of control, as well as feelings of distress following the episode. The presence of BED increases the risks of depression and poor quality of life above those associated with obesity alone. (4–6)

Obese patients with BED who receive a comprehensive behavioral weight loss program report improvements in both mood and quality of life. (7, 8) Researchers are uncertain whether improvements are attributable to weight loss, to participants’ receipt of group social support, or to cognitive behavioral elements of the treatment (present in most lifestyle modification programs), designed to correct maladaptive thinking habits that affect eating and mood. Surgically-induced weight loss also is associated with improvements in mood(9, 10) typically in the absence of adjunctive lifestyle modification or significant social support. These findings suggest that weight loss alone is sufficient to improve mood (at least in the short-term).

The present prospective observational study compared changes in mood and quality of life in obese participants with BED who received a 1-year behavioral weight loss intervention with changes in the same outcomes in patients with BED who underwent bariatric surgery. Participants were assessed at baseline, 2, 6, and 12 months follow-up. We hypothesized that participants undergoing bariatric surgery (provided without any adjunctive group lifestyle modification), would experience greater improvements in mood and quality of life than participants receiving a comprehensive behavioral intervention which induced weight loss and provided cognitive skills training and social support. Previous work has shown that greater reductions in body weight are associated with larger reductions in symptoms of depression (11). . In addition, we hypothesized that psychosocial improvements would be positively related to weight loss, collapsing across the two treatment groups.

Methods

Procedures

Participants were enrolled in the study as described previously in detail.(10) All procedures were approved by the xxxxxxxxx Institutional Review Board. Surgery participants were recruited from the Bariatric Surgery Program at the xxxxxxxx and underwent behavioral assessment by a mental health professional to ensure that they did not have any behavioral contraindications to surgery (the usual practice for all bariatric surgery candidates at xxxxxxxxx). At the end of this evaluation, the assessor referred participants to a research coordinator if they expressed interest in the study. The research coordinator presented the study in detail, performed relevant screening assessments, and obtained written informed consent.

Candidates for the lifestyle modification group were recruited via advertisements in the local media. Those who appeared to meet eligibility criteria attended an in-person interview with a psychologist who obtained written informed consent. Participants had to be at least 18 years of age and have a body mass index ≥ 40 kg/m2 or ≥ 35 kg/m2 in the presence of obesity-related co-morbidities. Candidates with a history of cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, kidney, or liver disease, type 1 diabetes, or uncontrolled hypertension, as well as those reporting severe symptoms of depression (defined by a score of >28 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II(12)), were excluded. Participants could not be pregnant or lactating, use medications known to affect body weight (e.g., oral steroids or psychiatric medications that induce weight gain), or have lost ≥ 5% of their initial weight in the prior 3 months. (These were the same general guidelines used to evaluate candidates’ appropriateness for surgery, as described previously (10).)

At the screening visit, all candidates (surgery and lifestyle modification) completed the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns,(13) which assesses binge-eating behavior. As described previously,(11) trained assessors then administered an abbreviated version of the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE),(14) to assess for the presence of objective binge episodes (OBEs). These refer to eating an objectively large amount of food in a short (2 hr) period of time, accompanied by loss of control and associated feelings of distress. Participants were diagnosed with BED if they reported at least one OBE per week for the past 3 months, reported associated distress, and were free of bulimic symptoms. All participants in the current analysis met these criteria for BED, using these proposed DSM V criteria. (15)

Intervention

In this observational study, participants chose to undergo either bariatric surgery or lifestyle modification

Surgery

Surgery participants chose Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or adjustable gastric banding surgery, based on their own preference and the medical advice of their surgeon. Each procedure was performed laparoscopically following methods described previously.(10) The research team was not responsible for any aspects of the patients’ medical eligibility to undergo surgery.

Lifestyle intervention

A group program of lifestyle modification was provided to the participants in the lifestyle intervention group (who did not seek surgery). They attended weekly group sessions from weeks 1 to 20, every-other-week meetings from week 22 to 40, and monthly sessions through week 52. Sessions were led by a clinical psychologist, who followed a written protocol (described previously(10)). Sessions lasted 90 minutes, and included 7–10 participants. From weeks 3–14 participants were prescribed a 1200–1300 kcal/d diet that combined 4 servings of liquid shakes (Health Management Resources (HMR) 800; HMR; Boston, MA) with a frozen food entrée. At week 14, participants reduced their liquid shake intake so that by week 18 they consumed a diet of conventional foods of 1400–1600 kcal/d. Participants were encouraged to gradually increase their physical activity to 180 min per week of aerobic exercise (principally brisk walking).

Outcome Measures

Weight

Participants were weighed on a digital scale (Detecto 6800A, Detecto, Webb City, MO), dressed in light clothing without shoes. Baseline weight measurements were taken 1 week prior to the lifestyle modification intervention and 1–2 weeks prior to surgery. Assessments were also obtained at months 2, 6, and 12. The self-report questionnaires described below were completed prior to the weight assessment.

Depression

Symptoms of depression were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses mood over the previous week. Total scores range from 0–63, with higher scores indicating greater symptoms of depression. Scores of 0–13 reflect minimal (i.e., subclinical) symptoms, whereas values of 14–19, 20–28 and > 29 indicate mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of depression, respectively.(12)

Quality of Life

The Medical Outcomes Scale, Short Form-36 version 2 (SF-36 v2) was used to assess quality of life.(16) The SF-36 is a 36-item health questionnaire that yields an overall profile of functional health scores, as well as two summary variables -- the physical component score and the mental component score -- which are calculated to reflect quality of life related to physical and mental functioning, respectively. The SF-36 assesses multiple indicators of health, including behavioral function and dysfunction, distress and well-being, objective reports and subjective ratings, and both favorable and unfavorable self-evaluations of general health status. (17, 18)

Binge-Eating

The number of days (in the previous 28 days) in which participants experienced OBEs was assessed using the EDE (14).

Statistical Analyses

For the main analyses examining changes in weight, mood and quality of life, data were included for all participants who received treatment (i.e., surgery or at least one lifestyle modification session) and provided at least one post-baseline measure of body weight and BDI-II. Participants who only provided baseline measures were excluded because we were most interested in changes in outcomes over time, and the linear mixed models used to analyze longitudinal change in the outcomes (described below) required at least one post-baseline measure.

Using this modified intention-to-treat (mITT) sample, differences in baseline characteristics between the surgery and lifestyle modification groups were first analyzed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Changes in weight, mood, and quality of life were examined using linear mixed models with maximum likelihood estimation, which accounted for the correlation among repeated measures. These analyses controlled for initial BMI, type of surgery, age, gender, ethnicity and the baseline value of the outcome. As stated above, this analytic approach allowed all participants with at least one post-baseline measure were able to contribute to the analyses.

The primary outcome was change in BDI-II scores at month 12 for participants receiving surgery vs. lifestyle modification, with an alpha set at p<0.05. Secondary analyses included changes in BDI-II score at months 2 and 6, as well as changes in SF-36 subscale scores at months 2, 6, and 12. All secondary comparisons were examined at p≤0.016, using Bonferroni adjustment for comparisons at multiple time points.

In addition, we examined whether the magnitude of weight loss was associated with greater changes in depression or quality of life via a completer’s analysis (n=59). Coefficients yielded by these analyses indicate the magnitude of change in the dependent variable (BDI-II score) that can be expected with every unit of change in the independent variable (percent weight loss).

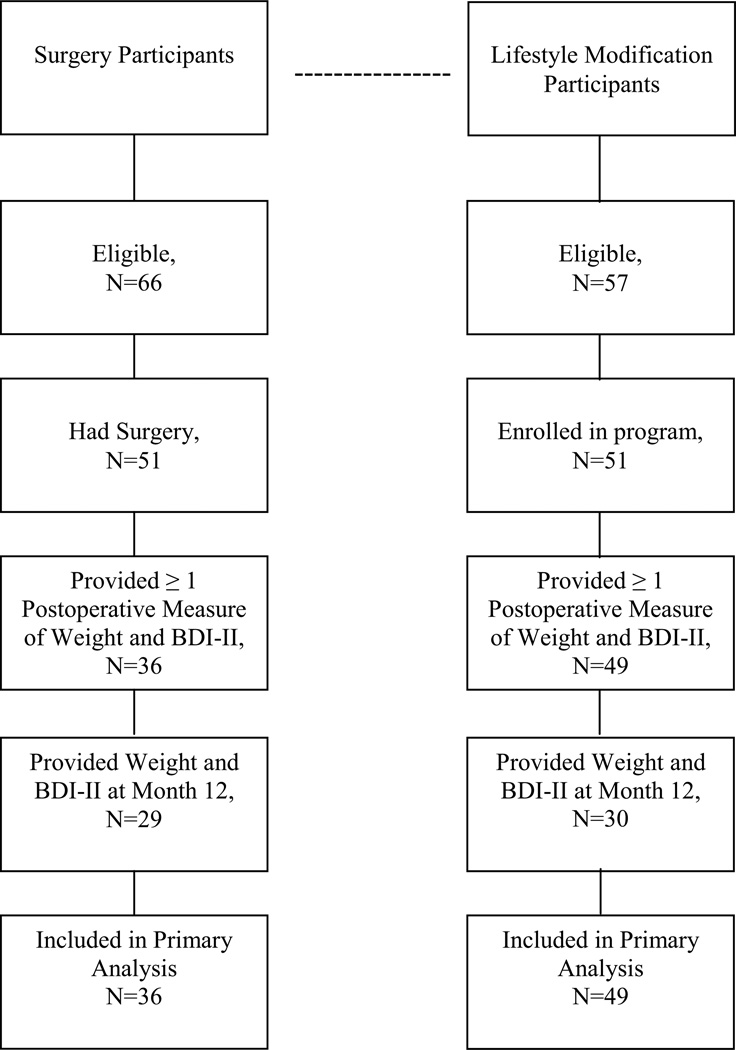

Participant Enrollment and Retention

As shown in Figure 1a total of 66 surgery applicants were identified who wished to participate, of whom 51 ultimately had surgery. (Fifteen participants either were denied insurance coverage or decided against surgery.) Of these 51, 36 (70.6%) returned for at least one post-operative assessment of both body weight and mood (at 2, 6, or 12 months). At month 12, 30 (58.8%) of surgery candidates returned for a weight measurement, and 29 (56.9%) returned for both assessments. For the lifestyle modification participants, a total of 82 individuals completed an initial evaluation with the psychologist, of whom 57 met inclusion/exclusion criteria. Fifty-one participants enrolled in the study, 49 (96.1%) provided a post-baseline measurement of both body weight and depression, and 42 (82.4%) provided a weight at month 12, and 30 (58.8%) provided both measures at month 12. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing participant recruitment.

BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II

Results

Participants’ Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of participants in the surgery and lifestyle modification groups are shown in Table 1. The two groups were similar on age (47.0 ± 1.6 vs. 43.8 ± 1.4 yr) and baseline BDI-II score (12.2 ± 1.3 vs. 15.5 ± 1.6), but significantly different on other baseline variables, such as BMI (48.9 ± 1.1 vs. 44.3 ± 0.7 kg/m2), as expected. (Participants seeking surgery are typically heavier than those who seek weight reduction with diet and exercise.) The surgery group had a lower percentage of African American participants than did the lifestyle modification group (22.2% vs. 53.1%), and surgery participants reported lower scores on the Bodily Pain subscale of the SF-36 (39.5 ± 1.6 vs. 44.8 ± 1.6). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the Surgery and Lifestyle Modification groups.

| Surgery (% or ± SE) |

Lifestyle Modification (% or ± SE) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 36 | 49 | |

| Gender | .450 | ||

| Female | 26 (72.2%) | 39 (79.6%) | |

| Male | 10 (27.8%) | 10 (20.4%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | .005 | ||

| African American | 8 (22.2%) | 26 (53.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 0 | 3 (6.3%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 27 (75%) | 18 (36.7%) | |

| Other | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| Education | .632 | ||

| <12th grade | 1 (2.8%) | 3 (6.1%) | |

| High school/GED | 12 (33.3%) | 12 (24.5%) | |

| Some College | 7 (19.4%) | 14 (28.6%) | |

| Bachelors Degree | 9 (25%) | 14 (28.6%) | |

| Graduate Degree | 7 (19.4%) | 6 (12.2%) | |

| Age (yr) | 47.0 ± 1.6 | 43.8 ± 1.4 | .141 |

| Weight (kg) | 139.7 ± 4.3 | 125.8 ± 2.9 | .006 |

| Height (cm) | 168.8 ± 1.5 | 168.2 ± 1.2 | .743 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 48.9 ± 1.1 | 44.3 ± 0.7 | .001 |

| BDI-II | 12.2 ± 1.3 | 15.5 ± 1.6 | .130 |

| OBE days | 9.5 ± 1.2 | 13.0 ± 0.9 | .022 |

| SF-36 | |||

| Physical Functioning | 34.9 ± 1.9 | 37.3 ± 1.5 | .324 |

| Role Physical | 41.8 ± 1.7 | 43.7 ± 1.5 | .406 |

| Bodily Pain | 39.5 ± 1.6 | 44.8 ± 1.6 | .024 |

| General Health | 38.6 ± 1.7 | 41.4 ± 1.4 | .208 |

| Vitality | 39.0 ± 1.6 | 42.7 ± 1.4 | .087 |

| Social Functioning | 38.3 ± 2.0 | 42.7 ± 1.7 | .107 |

| Role Emotional | 42.3 ± 1.7 | 43.7 ± 1.8 | .596 |

| Mental Health | 43.5 ± 1.8 | 44.8 ± 1.7 | .612 |

| Physical Component | 37.7 ± 1.7 | 40.8 ± 1.3 | .155 |

| Mental Component | 43.1 ± 1.6 | 45.4 ± 2.0 | .422 |

Note: Only 31 participants in the Surgery group completed the full SF-36 at baseline. SE = standard error; GED = general education diploma; BMI = body mass index; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; OBE = objective binge episode; SF-36 = Short Form 36

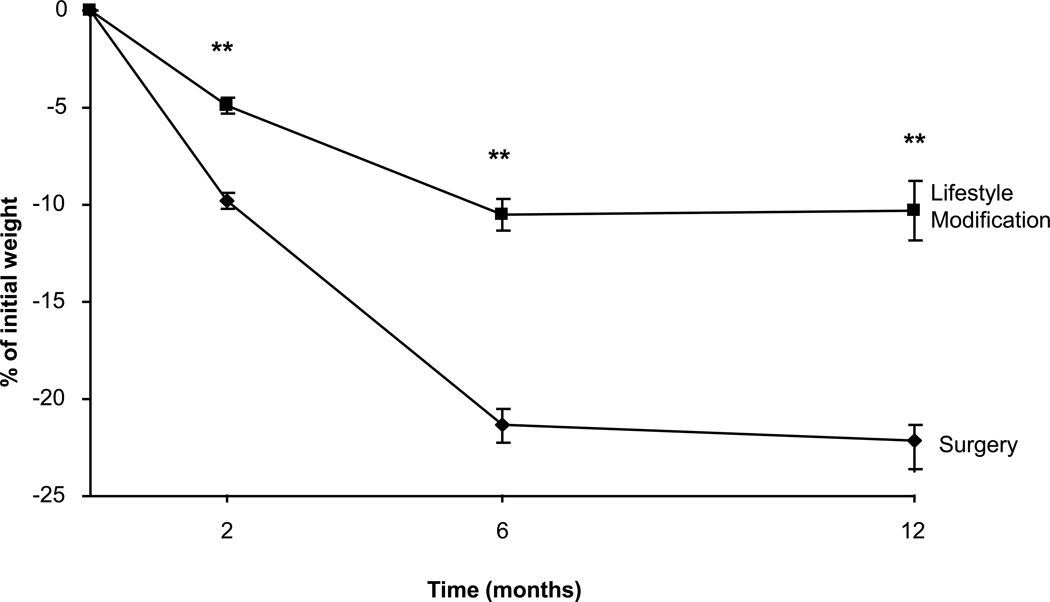

Weight

As reported previously(10) (and shown in Figure 2), participants who received bariatric surgery lost significantly more weight at all assessments than those who received lifestyle modification (all p values < 0.001). Mean losses at 2 months were 9.8 ± 0.4% vs. 4.9 ± 0.4% of initial weight; at 6 months were 21.3 ± 0.9% vs. 10.5 ± 0.8%; and at 12 months were 22.1 ± 1.7% vs. 10.3 ± 1.5%, respectively. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Mean (± SE) changes in percent weight lost by participants in the surgery (diamond; n = 36) and lifestyle modification (squares; n = 49) groups at 2, 6 and 12 months. ** indicate p’s <0.001

Binge-Eating Behavior

As reported previously (10), the number of days in which participants experienced OBEs declined sharply in both the surgery and lifestyle groups during the first 6 months (mean reductions of 9.5± 0.9 and 13.0 ± 0.8 days, respectively, ns), with slight increases in the number of days at month 12 (mean reductions of 7.7 ± 1.5 and 9.1 ± 1.5 days, respectively, from baseline, ns). There were no significant differences between groups in changes in binge days at any time points (all p’s >0.18)

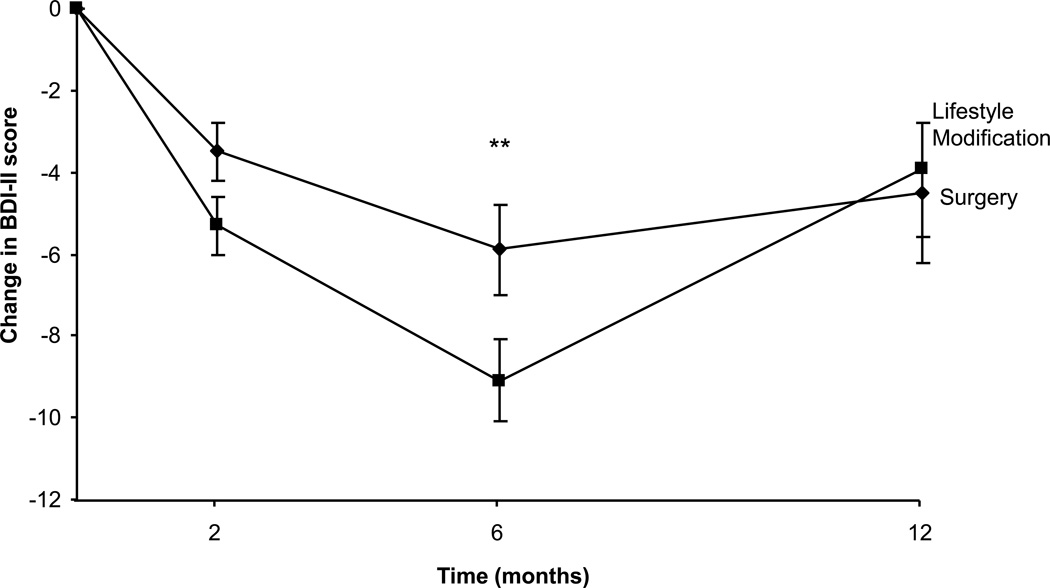

Symptoms of Depression

The primary outcome, which compared changes in BDI-II score at month 12 in the surgery and lifestyle modification groups, yielded a null result (p=0.801); there was no significant difference between groups in changes in symptoms of depression (decreases of 4.5 ± 1.7 vs. 3.9 ± 1.7, respectively; Figure 3). The pattern of results was preserved when controlling for change in OBE days (data not shown). Secondary analyses showed that there were also no significant differences in changes in symptoms of depression at month 2. At 6 months participants in the lifestyle modification group reported a decrease of 9.1 ± 1.0 points on the BDI-II, compared to 5.9 ± 1.1 points for the surgery group, which approached statistical significance using the Bonferroni correction (p=0.039). Collapsing across participants in both groups, BDI-II scores declined from 14.1 ± 1.1 at baseline to 8.7 ± 1.1 at month 12 (p<0.001), indicating significant improvements in symptoms of depression. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Mean (± SE) changes in Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) score reported by participants in the surgery (diamonds; n = 36) and lifestyle modification (squares; n = 49) groups at 2, 6 and 12 months. ** indicate p’s <0.001

Quality of Life

Changes in SF-36 scores are presented in Table 2. Secondary outcomes were changes in the mental component summary (MCS) score and physical component summary (PCS) score at month 12. There were no significant differences between groups in changes in the MCS (p=0.523) or PCS scores (p=0.221) at 12 months. Additional analyses also compared differences between groups on these two measures and on the 8 individual subscales at each assessment period. At month 6, the surgery group showed significantly greater improvements in the MCS score (p<0.007), social functioning (p<0.001), and mental health scores (p<0.010) than did the lifestyle modification group. A similar pattern of results was observed at month 2. These differences were not significant at 12 months. No differences in the physical component summary (PCS) score, or in any of the subscales that contribute to that score, were observed between the two groups at any time. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Changes in the Short Form-36 scores across the year in Surgery and Lifestyle Modification groups.

| Variable | 2 months |

6 months |

12 months |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Lifestyle | p-value | Surgery | Lifestyle | p-value | Surgery | Lifestyle | p-value | |

| Physical Component | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 0.34 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 1.0 | 0.674 | 8.7 ± 2.1 | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 0.221 |

| Mental Component | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.016 | 7.5 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 0.007 | 2.4 ± 2.7 | 0.1 ± 2.4 | 0.523 |

| Subscales: | |||||||||

| Physical Functioning | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± .06 | 0.687 | 10.7 ± 1.3 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 0.164 | 10.9 ± 2.1 | 6.9 ± 1.9 | 0.172 |

| Role Physical | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 0.982 | 8.4 ± 1.4 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 0.207 | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 1.9 | 0.499 |

| Bodily Pain | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | 0.551 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 0.066 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 0.465 |

| General Health | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 0.328 | 7.4 ± 1.3 | 7.6 ± 1.0 | 0.915 | 8.4 ± 2.0 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 0.086 |

| Vitality | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 0.508 | 11.4 ± 1.5 | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 0.107 | 7.5 ± 2.6 | 5.2 ± 2.2 | 0.520 |

| Social Functioning | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 0.034 | 11.2 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 0.001 | 5.3 ± 2.5 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 0.382 |

| Role Emotional | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 0.163 | 6.2 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.067 | 3.2 ± 2.5 | 2.3 ± 2.2 | 0.789 |

| Mental Health | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.016 | 6.9 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.2 | 0.010 | 1.8 ± 2.4 | 0.1 ± 2.1 | 0.601 |

Note: Values shown are mean (± SE) changes from baseline, as assessed at month 2, 6, and 12. P values show the comparison between the Surgery and Lifestyle Groups at each time point. Bolded values represent statistical significance at the p≤0.016 level (to account for comparisons at multiple time points). Increases on the Short Form-36 subscales represent improved functioning.

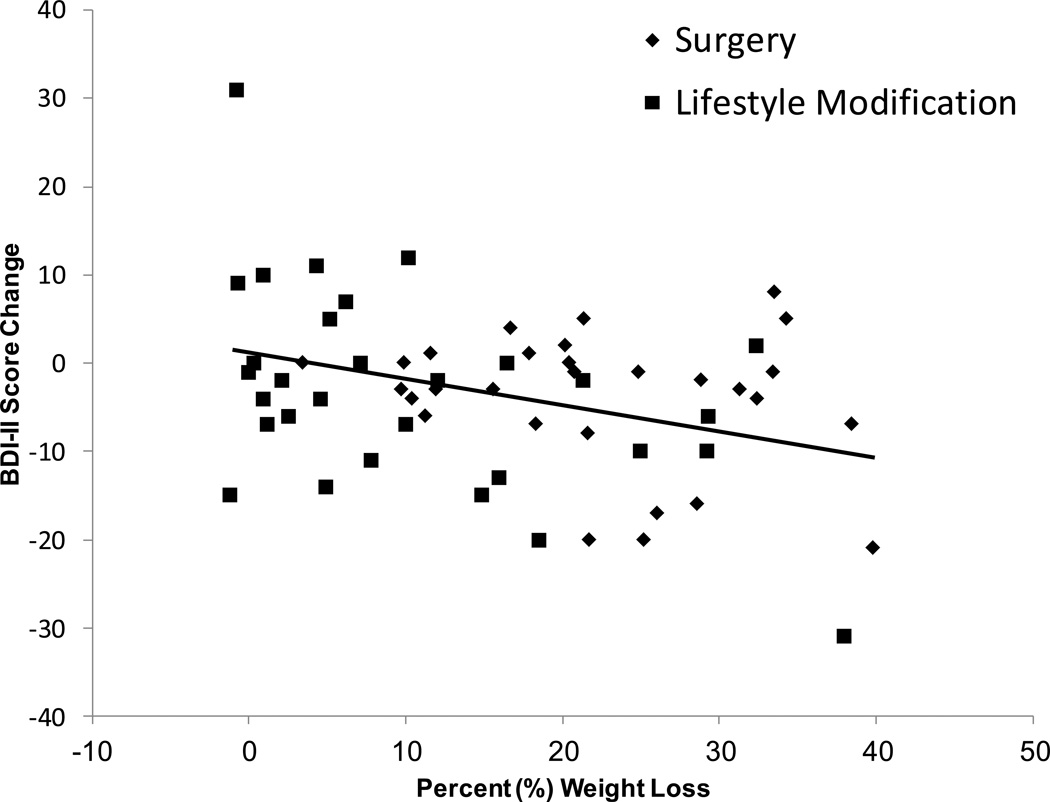

Relationship between Magnitude of Weight Loss and Changes in Symptoms of Depression

We used a completers analysis to examine the relationship between weight loss and changes in BDI-II score. Fifty-nine participants (29 surgery and 30 lifestyle participants) were weighed and completed BDI-IIs at baseline and 1 year. Collapsing across the surgery and lifestyle groups (n = 59), percent weight loss and change in BDI-II score were significantly associated (coefficient = 32.7, SE = 10.1, t = 3.25, p < 0.002), indicating that the greater the weight loss, the greater the improvement in symptoms of depression, see Figure 4. The model suggested that each 1% of initial body weight lost was associated with an improvement in BDI-II score of approximately 0.33 (e.g., a 10% weight loss was associated with an estimated improvement of approximately 3.3 in BDI score). Furthermore, percent weight loss prospectively predicted (p < 0.003) change in BDI-II score at the subsequent assessment time point (e.g., percent weight loss at month 2 predicted change in BDI-II score at month 6 and weight loss at month 6 predicted change in BDI-II score at month 12), which was independent of the treatment received (coefficient = 10.7, SE = 12.6, t = 0.87, p = 0.39). In contrast, BDI-II score change did not prospectively predict weight loss, either across the sample (coefficient = 0.0004, SE = 0.0009, t = 0.625, p = 0.625) or in the surgery and lifestyle modification groups (coefficient = 0.001, SE = 0.009, t = 1.697, p = 0.091). (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Change in Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) score by percent weight loss for individual participants in the surgery (diamonds; n = 36) and lifestyle modification (squares; n = 49) groups at 12 months.

Discussion

The current analysis was undertaken to examine whether surgery participants with BED (receiving no behavioral intervention) would show greater improvements in mood and quality of life than non-surgery participants with BED undergoing a typical treatment of lifestyle modification. Our primary outcome assessed changes in symptoms of depression at 12 months and yielded no differences between the two intervention groups, including when controlling for changes in binge-eating behavior. These results suggest that participants choosing surgery or lifestyle modification treatments can expect comparable changes in symptoms of depression up to 1 year. These findings support earlier work suggesting clinically significant improvements in mood following surgical interventions in the absence of additional treatment factors provided by behavior modification.(20, 21)

Regression analyses (which combined the two groups) showed a positive relationship between weight loss and symptoms of depression at month 12, indicating that the greater the weight loss, the greater the reduction in symptoms of depression. These data notwithstanding, it is likely that weight loss alone does not fully explain the reductions in symptoms of depression, otherwise the participants in the surgery group (who lost significantly more weight than participants in the lifestyle group) would have shown even greater reductions in their symptoms of depression. Alternatively, it is possible that we did not have adequate power to detect differences in mood between the two intervention groups.

Secondary analyses, which examined changes in mood in the short term (after 6 months of treatment), showed slightly larger improvements in mood in participants who received lifestyle modification compared to those who received bariatric surgery (clinically meaningful reductions of 9.1 vs. 5.9 points on the BDI-II, respectively). The difference approached statistical significance using Bonferroni adjustment, despite the fact that the surgery group lost almost twice as much weight as the lifestyle group. The short-term improvements in mood in the lifestyle group may reflect the beneficial effect of weight loss combined with group social support and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Support for this belief is suggested by the worsening in mood observed in the lifestyle participants between months 6 and 12. BDI-II scores increased from 6.3 points at 6 months to 11.7 points at 12 months (data not shown), even though participants maintained the level of weight loss (~10% of initial weight) achieved at month 6. It is noteworthy that weekly treatment visits were terminated at month 6, and the groups met every-other-week until month 9, and then only once every 4 weeks between months 9 and 12. This dilution in the “dose” of lifestyle modification may have contributed to the worsening in mood observed between 6 and 12 months. Alternatively it is possible that participants became discouraged as their weight plateaued during months 6–12 when they wanted to continue losing weight. A randomized controlled trial will be necessary to determine the possible short- and long-term contributions of social support and/or cognitive therapy to changes in mood within a lifestyle intervention.

Across all study participants, change in weight at one time point predicted change in BDI-II score at the next time point; conversely, change in BDI-II score did not predict weight loss at the next time point. These results suggest that improvements in symptoms of depression follow weight loss, but that weight loss does not necessarily follow improvements in mood. Longer-term follow-up is required to determine whether improvements in mood persist in surgery patients who receive no cognitive-behavioral teaching or group support, and in those who do (or don’t) maintain large weight losses.

Quality of life, as measured by the mental and physical component summary scores on the SF-36, improved in both groups across the year. Surgery participants reported greater improvements than lifestyle participants in social functioning, mental health, and the mental health component summary (MCS) score at 6 months, but there were no differences between the groups by 12 months. These results support our general conclusions that participants choosing surgery or lifestyle modification can expect similar improvements in both mental and physical dimensions of quality of life at 1 year.

Our study was limited by the relatively non-depressed sample from which to judge improvements in symptoms of depression. The baseline BDI-II score for both groups indicated mild symptoms of depression, limiting the room for large improvements to be observed, although approximately half of each group reported scores >14 on the BDI-II, indicating at least mild symptoms of depression at baseline. Moreover, improvements of at least 5 points were observed in both groups at 6 months, a change considered clinically meaningful.(19) It is possible, however, that participants with Major Depressive Disorder, as diagnosed by a structured clinical interview, may have shown greater (or lesser) changes in mood. In addition, this study was observational and participants opted for treatment (surgery or lifestyle modification) rather than being randomly assigned to either one. Attrition rates in both the surgery and lifestyle groups were high, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Finally, caution is advised in interpreting the results for participants with BED who received bariatric surgery vs. lifestyle modification: the two groups may differ in important ways beyond their motivation for their respective treatments.

Conclusion

These limitations notwithstanding, our results highlight the beneficial effects of either surgery or lifestyle modification program on symptoms of depression and quality of life for obese individuals with BED. We hope that these results provide encouragement for individuals for whom surgery is not an option by showing that alternative treatments can produce comparable benefits in mood and quality of life for periods up to 1year. As noted previously, the dose of lifestyle modification in this study was reduced to every other week at 6 months, and to once a month at 9 months (as is standard practice), which may explain some of the deterioration in mood observed in these participants by month 12. It is possible that maintaining a higher “dose” of lifestyle modification treatment may help bolster mood over the longer term. Future studies should monitor the longer-term outcomes in both surgery and lifestyle participants, as they potentially regain lost weight, and compare improvements in mood and weight in participants receiving combined treatments (surgery plus lifestyle modification or pharmacotherapy) to the individual treatments provided in the current study.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grants DK069652 and K23HL109235.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kolotkin RL, Westman EC, Ostbye T, Crosby RD, Eisenson HJ, Binks M. Does binge eating disorder impact weight-related quality of life? Obes Res. 2004;12:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malone M, Alger-Mayer S. Binge status and quality of life after gastric bypass surgery: a one-year study. Obes Res. 2004;12:473–481. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pagoto S, Bodenlos JS, Kantor L, Gitkind M, Curtin C, Ma Y. Association of major depression and binge eating disorder with weight loss in a clinical setting. Obesity. 2007;15:2557–2559. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DE, Marcus MD, Lewis CE, Fitzgibbon M, Schreiner P. Prevalence of binge eating disorder, obesity, and depression in a biracial cohort of young adults. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02884965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Specker S, de Zwaan M, Raymond N, Mitchell J. Psychopathology in subgroups of obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35:185–190. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, Spitzer RL. Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1472–1479. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladis MM, Wadden TA, Foster GD, Vogt RA, Wingate BJ. A comparison of two approaches to the assessment of binge eating in obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23:17–26. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199801)23:1<17::aid-eat3>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nauta H, Hospers H, Jansen A. One-year follow-up effects of two obesity treatments on psychological well-being and weight. Br J Health Psychol. 2001;6:271–284. doi: 10.1348/135910701169205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadden TA, Faulconbridge LF, Jones-Corneille LR, et al. Binge eating disorder and the outcome of bariatric surgery at one year: a prospective, observational study. Obesity. 2011;19:1220–1228. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruusunen A, Voutilainen S, Karhunen L, Lehto SM, Tolmunen T, Keinänen- Kiukaanniemi S, Eriksson J, Tuomilehto J, Uusitupa M, Lindström J. How does lifestyle intervention affect depressive symptoms? Results from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabet Med. 2012;29:e126–e132. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck A, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) San Antonio, Tx: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spitzer RL, Devlin M, Walsh TB, et al. Binge eating disorder: A multisite field trial of the diagnostic criteria. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. 12th ed. New York: Guildford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. [Assessed 22 April 2010];DSM-5 Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Binge Eating Disorder. http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=372.

- 16.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to Score Version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. Lincoln, Rhode Island: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE. Measuring patients' views: the optimum outcome measure. BMJ. 1993;306:1429–1430. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faulconbridge LF, Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, et al. Changes in symptoms of depression with weight loss: Results of a randomized trial. Obesity. 2009;17:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O'Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2058–2065. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson J, Taft C, Rydén A, Sjöström L, Sullivan M. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes. 2007;31:1248–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]