Abstract

IgG is a molecule that functionally combines facets of both innate and adaptive immunity and therefore bridges both arms of the immune system. On the one hand, IgG is created by adaptive immune cells, but can be generated by B cells independently of T cell help. On the other hand, once secreted, IgG can rapidly deliver antigens into intracellular processing pathways, which enable efficient priming of T cell responses towards epitopes from the cognate antigen initially bound by the IgG. While this process has long been known to participate in CD4+ T cell activation, IgG-mediated delivery of exogenous antigens into a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I processing pathway has received less attention. The coordinated engagement of IgG with IgG receptors expressed on the cell-surface (FcγR) and within the endolysosomal system (FcRn) is a highly potent means to deliver antigen into processing pathways that promote cross-presentation of MHC class I and presentation of MHC class II-restricted epitopes within the same dendritic cell. This review focuses on the mechanisms by which IgG-containing immune complexes mediate such cross-presentation and the implications that this understanding has for manipulation of immune-mediated diseases that depend upon or are due to the activities of CD8+ T cells.

Keywords: Fcγ receptor, FcRn, Cross-presentation, IgG, Immune complex, Dendritic cells

Introduction

Multicellular organisms continuously encounter potential pathogens and damaged cells and have thus developed a multilayered defense arsenal to maintain physiological homeostasis. Integration of the various branches of this immunological defense system is critical for efficient and optimal protection against invasive threats. The initiation point for much of this cross-talk between the humoral and cellular components of innate and adaptive immunity is the manner in which the perturbation is first sensed, which has an important role in determining the direction of the ensuing immune response. Typically, recognition of an immunological target is mediated by receptors which either bind to conserved sequences localized on the cell surface, such as pattern recognition receptors (PRR) specific for pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), or to unique sequences contained within secreted molecules such as complement or immunoglobulins (Ig), which in the latter case can be secreted or expressed on the cell surface [1]. Immunoglobulins, including IgG, are unique in that they may be produced and function in both the innate and adaptive arenas of the immune response. Specifically, IgG can be produced by B cells via both T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms, the latter of which allows for IgG participation in immediate defense as well as in the initial orchestration of an immune response through a variety of processes [2, 3]. For example, the interaction of IgG with a ligand is commonly associated with neutralization or targeting for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) [4]. However, it is being increasingly recognized that Ig, particularly of the abundant IgG isotype, are potent integrators of innate and cellular immunity by virtue of their ability to deliver opsonized antigen(s) to antigen presenting cells (APC) lacking antigen specific receptors, thereby enabling the priming of T cell responses towards cognate antigen.

Monomeric IgG, either unbound by antigen or bound to a single antigenic epitope, are efficiently recycled out of most cells, including epithelial, endothelial, and B cells [5–8]. This process of exocytosis, which has also indirectly been shown for APC such as dendritic cells (DC), accounts for the long half-life of IgG in circulation [9, 10]. In contrast, multivalent IgG-opsonized antigens are able to bind to low-affinity IgG receptors on APC via their Fc region resulting in cross-linking of the receptors and subsequent internalization of the antigens. Once internalized, such extracellular antigens are typically routed to intracellular compartments capable of processing and presenting nominal peptides from the antigens in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, which are displayed on the cell surface for interactions with CD4+ T cells [11]. Such IgG-binding Fcγ receptor (FcγR)-mediated endocytosis, processing, and presentation are an important and effective means of promoting T cell activation to extracellular antigens [11, 12]. In turn, these responses are important in the protection against extracellular pathogens through the elicitation of CD4+ T cell help for the generation of antibodies with high affinity and avidity [13–15]. Presentation of epitopes from such exogenously acquired antigen on MHC class I molecules, however, also occurs in a process known as cross-presentation which, when first described, countered the long-held dogma that MHC class I could only be loaded with endogenously acquired antigen [16–19]. Such cross-presentation allows the APC to effectively prime CD8+ T cells to antigens associated with pathogens that target intracellular locales and which need such effector functions for their cytolytic removal. As such, a single APC can simultaneously cross-present antigens via MHC class I to CD8+ T cells and present antigens via MHC class II to CD4+ T cells which provide the T cell help necessary for initiating CD8+ T cell effector responses [20–22]. This elegant system allows for a unique geographic localization of both pathways for optimal efficacy. While a variety of APC are capable of presenting exogenously derived antigens on MHC class II molecules, only DC have so far been recognized to efficiently cross-present antigens in vivo [23, 24]. In large part, this has been attributed to their specialized intracellular processing machinery yet the sensitivity of the process can be greatly enhanced by targeted delivery of antigen to specific membrane receptors such as DEC-205 [25–27]. The presence of members of the FcγR family on the surface of most DC in addition to the expression of an intracellular routing IgG receptor, the neonatal Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn), within DC generates a natural system for highly efficient delivery of antigen into a cross-presentation pathway capable of promoting defense against intracellular pathogens and tumor cells while also contributing to the balance between tolerance and autoimmunity [28, 29]. This review will focus on recent insights into the mechanisms of cross-presentation when initiated by IgG-containing immune complexes and IgG-opsonized antigens and the pathophysiological importance of this process.

Cross-presentation of soluble antigens

We will introduce this topic by first considering DC and the manner in which this subset of cells cross-present non-opsonized (or soluble) antigens as a basis for understanding the cross-presentation of IgG-associated antigens. DC are a very diverse population of cells consisting of a variety of different subsets, the frequency of which varies according to both tissue localization and context [30, 31]. Two broad populations of DC can be described, conventional CD11c+ DC, which originate from a myeloid precursor, and plasmacytoid DC (pDC), which originate from a lymphoid precursor [32]. Conventional DC can further be subdivided into CD8+CD11b− and CD8−CD11b+ subsets within lymphatic tissue and CD103+CXCR3−CD8+CD11b− and CD103−CXCR3+CD8−CD11b+ subsets within tissues [32–35]. Under inflammatory conditions, tissues are also commonly invaded by a population of monocyte-derived CD8−CD11b+ DC which arise from circulating monocytes yet are capable of DC functions [36]. Critically, while considerable plasticity exists within DC populations, it is likely that the complement of cell-surface and intracellular machinery exhibited by a particular DC at any point in time will dictate its functional capacity [30, 32].

It is thus not surprising that DC subsets are heterogeneous in their ability to cross-present soluble antigens. In mice, it is largely the CD8+ or CD103+ subsets of DC which drive this process whereas in humans, cross-presenting DC are CD141+ (BDCA3+) [37–39]. Although recent studies have also documented the ability of other DC subsets to drive cross-presentation of soluble antigen in vitro, in the absence of additional stimuli, as discussed below, the efficiency with which these other DC subsets have been found to activate CD8+ T cells is consistently inferior to that of CD8+ DC [40, 41]. Thus, while a role for other DC types in driving cross-presentation of soluble antigen cannot be ignored, particularly in in vivo settings where considerable cross-talk is likely to occur between cell populations at different stages of their development, the extreme potency of CD8+ DC to conduct this process has been the prime focus of cross-presentation research to date. To this effect, while the mode of antigen delivery to a DC can modulate the efficiency of cross-presentation, it is not specialized antigen capture which endows the CD8+ DC lineage with superior cross-presenting capabilities for soluble antigen [40, 42]. Rather, their specific phenotype is associated with a specialized intracellular machinery that allows these cells to exhibit slow antigen degradation that results in the prolonged persistence of relatively intact antigen and the resulting preservation of epitopes conducive to loading onto MHC class I molecules [43–45]. A key element of this behavior is the manner in which the endosomes of such DC subsets undergo acidification. The endosomal compartments of typical phagocytes such as macrophages and neutrophils acidify to pH <5.0, which corresponds well with the optimal proteolytic activity of many lysosomal proteases located within these compartments [46]. While this permits highly efficient neutralization of potentially harmful phagocytic cargo and the generation of antigens for loading onto MHC class II molecules, it is generally believed that this also destroys epitopes capable of being loaded into the MHC class I groove, thereby precluding efficient cross-presentation by these cells. In contrast, the pH within endosomes and phagosomes of immature CD8+ DC, which excel at the cross-presentation of soluble antigens, remains stabilized in a neutral range (pH 7.0–7.5) [47]. This can be attributed to several processes, including the inefficient assembly of the vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) within these compartments, the delayed maturation kinetics of the phagosomes and the increased recruitment of ER proteins, the latter two of which have both been attributed to the actions of Sec22b [48–50]. Concomitantly, recruitment of an active NADPH oxidase, NOX2, to the phagosomal membrane within these DC leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); a process which actively consumes protons and thereby generates a sustained alkalinizing effect which is required for maintaining the compartmental pH near neutral [43]. NOX2 is delivered to phagosomes within these cells by fusion of “lysosome-related organelles” which are recruited in a Rab27a- and Rac2-dependent manner [44, 51]. While this process also delivers lysosomal proteins such as lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP) to the phagosomes, the continuous recruitment and action of NOX2 is sufficient to buffer the pH within these compartments and thus prevent the acidification seen in phagosomes of other phagocytes.

Details of how antigens are processed within this specialized cross-presentation pathway within CD8+ DC continue to emerge. Early studies have indicated that at least two major routes, dubbed the vacuolar or cytosolic pathways, exist by which the antigen may be processed [24]. The pathway which predominates likely depends upon the nature of the antigen and the mode of delivery into the cell. Soluble antigen in the vacuolar pathway is degraded in situ within the endosome or phagosome by resident proteases and the resulting peptides are then loaded directly onto empty endosomal MHC class I within the compartment [52–55]. This process is independent of both the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) and proteasomal degradation and depends on specific proteases such as cathepsin S [53, 56]. In contrast, antigen within the cytosolic cross-presentation pathway is first exported into the cytosol from the initial endosome or phagosome and, subsequent to ubiquitination, is proteasomally processed [57–59]. The peptides generated by this process are then either reimported into cross-presentation competent phagosomes or endosomes, in which they undergo further processing by the insulin regulated amino-peptidase (IRAP), or are transported back to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) at which point they can enter into the classical MHC class I loading pathway involving the related ER aminopeptidase (ERAP) [56, 60–62]. The latter conclusion has been based upon the TAP dependency often observed for this process and the known residence of TAP in the ER. Increasing evidence, however, indicates that fusion between the ER and various other intracellular compartments is not uncommon and that TAP might indeed be present in the phagosomes, thereby supporting early conclusions that phagosomes may be able to function as self-sufficient cross-presentation bodies [19, 57, 58].

Controversy persists as to which, if either, of these pathways predominates and under what circumstances an antigen is preferentially directed towards one mechanism or another. An important caveat likely lying at the heart of this dispute is that these studies have utilized not only a variety of DC in which to conduct mechanistic investigations but also a diverse array of antigens. In particular, most mechanistic studies have limited themselves to studying cross-presentation in the context of soluble antigens delivered in the absence of any co-stimulatory or maturation inducing signal. Given that the latter signals are known to drastically alter the microenvironment within internalizing endosomes or phagosomes, it is critical to consider such variables when attempting to generalize conclusions from a single study [48]. This point is made very salient by recent evidence demonstrating that plasmacytoid DC (pDC), which very inefficiently cross-present soluble antigen, are potent cross-presenters when the antigen is delivered in conjunction with a costimulatory signal such as CpG [63–67]. When considering the bulk of studies performed to date in which cross-presentation has been studied in the context of secondary co-stimulation, particularly that of PRR engagement by a microbial ligand, a clearer consensus emerges from the data. For example, in CD8+ DC isolated from mice suffering from mycobacterial peritonitis, IRAP is required for their cross-presentation function whereas it is dispensable for cross-presentation in steady-state CD8+ DC [68]. Furthermore, the vast majority of studies published to date having examined in vivo cross-presentation of bacterial (Salmonella typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli), viral (Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus) or protozoan (Toxoplasma gondii) antigen sources have identified proteasomal degradation as a critical step for the efficient induction of CD8+ T cell activation by DC [57, 69–75]. While not excluding a role for vacuolar proteases, these data imply that the antigen is preferentially shuttled into the cytosolic cross-presentation pathway when delivered in the context of an additional immunological stimulus which induces DC activation or maturation and thereby alters the intracellular environment. The precise mechanism behind this remains unknown in spite of the fact that a large proportion of in vivo antigenic stimuli are complex and likely to trigger such modulatory innate PRR during their uptake or subsequent processing.

Receptor contribution to cross-presentation

One of the first natural PRR recognized to play a role in cross-presentation of soluble antigen was the mannose receptor (MR), which is a C-type lectin receptor expressed both on the cell surface and intracellularly in a variety of cell types including macrophages and DC [76, 77]. This collagen-sensitive receptor mediates the uptake of soluble antigens by DC and directs this antigen into the early endosomal system, thereby segregating the antigen away from harshly degradative lysosomal compartments and promoting cross-presentation of the antigen [77, 78]. Furthermore, this receptor has been linked to cytosolic translocation of imported soluble antigen in a manner consistent with that seen for antigens delivered in the context of other secondary stimuli, as discussed above [79].

The greatly enhanced ability of MR-internalized antigen to elicit effective cross-presentation has not gone unnoticed by those seeking to target therapeutic molecules into this pathway [80]. Conjugates of antigen, such as the cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1, and MR-specific monoclonal antibodies have been shown to greatly improve cross-presentation of the desired antigen above that of the soluble protein alone [81]. Furthermore, this conjugate was shown to stimulate the activation of NY-ESO-1-specific CD8+ T cells, a process known as cross-priming, as well as of CD4+ T cells. Similar efficacies in driving specific CD8+ T cell responses were seen when NY-ESO-1 was fused to a monoclonal antibody specific for another receptor, DEC-205, which is also highly expressed on CD8+ DC [81–84]. Indeed, additional groups have successfully targeted antigen into a cross-presentation pathway using fusions with DEC-205-specific monoclonal antibodies [82, 85]. The success of this strategy has so far been attributed entirely to the ability of the antibodies to target the selected extracellular receptor. However, these fusions were constructed either by conjugating whole IgG with the desired protein or by including the protein as a genetically engineered in-frame fusion with the IgG heavy chain and, as such, the Fc region in the therapeutic molecule remains intact [81, 82, 85]. Thus, the interaction of the Fc region in these constructs with additional receptors capable of IgG binding by the DC cannot be entirely excluded when explaining their mode of action. Indeed, it is notable that the first receptors ever demonstrated to potentiate cross-presentation of antigen by DC were in fact FcγR [29, 86–88].

The extended IgG binding receptor family

The family of receptors which bind IgG was originally limited strictly to FcγR, which are expressed on the surface of a wide variety of hematopoietic cells. This family includes both activating and inhibitory Fc receptors and thus forms a tunable system capable of finely controlling the effects of IgG, the abundant levels of which in the blood can play a significant role in driving immune responses. Activating FcγR function largely through the action of an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motif (ITAM) which, in most cases, is located not in the alpha chain of the receptors themselves but rather in a co-associating dimeric adaptor molecule which, in APC, is known as the common γ-chain [89, 90]. Following ligand-induced phosphorylation of the ITAMs in the γ-chain dimer by SRC family kinases, the protein tyrosine kinase SYK is recruited via its two SH2 domains and then autophosphorylated, initiating a complex downstream signaling cascade [91–94]. The activating family of FcγR includes FcγRI, FcγRIII and FcγRIV in mice [90]. The human family is more complex, including several variants of FcγRI as well as additional activating FcγRIIa and FcγRIIc receptors, both of which possess an ITAM in their cytoplasmic tail and are thus capable of signaling independently of the common γ-chain [95–99]. In contrast, the inhibitory FcγR in both humans and mice is FcγRIIb, in which a single immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) is located in the cytoplasmic tail. Phosphorylation of this ITIM leads to the recruitment of phosphatases, particularly SHIP-1, which subsequently mediates the immunosuppressive effects caused by FcγRIIb ligation [100]. An additional layer of complexity in the FcγR system is that various gain-of-function and loss-of-function polymorphisms for most of these receptors have been described, some of which are known to alter either ligand binding or downstream signaling [101–103].

While the downstream signaling pathways initiated by ligand binding are remarkably similar between the different activating FcγR, ligand binding affinity varies widely depending on the IgG subclass as well the valency of the ligand. FcγRI has a very high affinity for monomeric human IgG1 and, considering that this subclass is the most abundant in the serum, this receptor is typically saturated with ligand under physiological conditions [104]. In contrast, FcγRII and FcγRIII bind with low affinity to monomeric IgG of any subclass but bind extremely strongly to multimeric IgG within immune complexes (IC). Binding of such multivalent ligands cross-links the receptors and potently initiates the signaling cascades described above. The relative strength of the signal is largely determined by the balance between the frequency of activating and inhibitory FcγR which are triggered, as well as by the valence of the complex and nature of the ligand to which the IgG is bound.

The family of IgG binding receptors was expanded beyond FcγR upon the discovery of an additional IgG binding receptor, FcRn, which is an MHC class I-like molecule requiring interaction with β2-microglobulin for proper folding and functioning [105–107]. While expression of this receptor was initially described only in the intestinal epithelial cells of neonatal rodents where it functions in the passive acquisition of IgG from the mother’s milk, it has since been shown to be expressed throughout life not only in adult human intestinal epithelial cells but also in epithelial cells of the placenta, lung and liver as well as in endothelial cells and the majority of hematopoietic cells in humans and rodents [108, 109]. Although transcytosis of maternal IgG across the placenta, in humans, or across the intestinal epithelium of suckling pups, in rodents, were the first functions ascribed to FcRn, this molecule is now known to play a critical role in the maintenance of circulating IgG levels as well as in mucosal and systemic immune regulation [9, 28, 110–115]. Importantly, the binding site for FcRn on the Fc region of IgG is distinct from that where FcγR binds and FcRn–IgG binding is independent of glycosylation at amino acid Asn297 which is critical for FcγR–IgG interactions [116]. The wide variety of functions carried out by FcRn can largely be attributed to a combination of its predominantly intracellular distribution and its highly specialized binding characteristics. Specifically, FcRn binds IgG specifically at pH ≤6.0 such that binding is minimal at the neutral pH of the cell surface but strong in the acidic environment of the endocytic and phagocytic compartments, thereby enabling FcRn to act as an intracellular receptor and transporter for IgG [117]. While it is known that the short cytoplasmic domain of FcRn contains both tryptophan- and dileucine-based basolateral targeting signals, two endocytosis signals (one each based on the combination of Trp311 with Leu314 and Leu322/Leu323 with Asp317/Asp318) and two serine phosphorylation sites (Ser313 and Ser319), the contribution, if any, of these domains to FcRn’s function in hematopoietic cells, particularly DC, remains unknown [118–120].

The diversity of receptors having evolved with IgG binding function as well as their distribution across a variety of cellular compartments and their relative evolutionary conservation across species clearly demonstrates the importance of both extracellular and intracellular IgG transport to organismal functioning. Although the first demonstration of IgG-driven cross-presentation by FcγR occurred many years ago, characterization of the mechanisms involved including possible cooperativity between the different IgG receptors and the physiological consequences of the process have only recently begun to be elucidated. Critically, the importance of cross-presentation in the context of concomitant signaling by IgG for the activation of specific CD8+ T cell responses is increasingly being recognized [121].

The contribution of cell-surface FcγR to cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigens

IgG binding by FcγR was first recognized to greatly increase the sensitivity of MHC class II presentation of exogenously derived IgG-complexed antigens and skew the repertoire of peptide epitopes generated for presentation [11, 12]. This was shown to depend upon signaling by the common γ-chain of activating FcγR but to be inhibited by ligation of the inhibitory FcγRIIb [11]. Shortly after this discovery, it was demonstrated that FcγR within immature DC also efficiently deliver antigens into an intracellular pathway conducive to cross-presentation [87]. Critically, delivery of antigen in this manner induced the concomitant maturation of the DC, as is typical for antigen delivery via a PRR, rendering it refractory to the cross-presentation of subsequent antigens contained within other IC likely by permanently altering the endolysosomal environment [48]. Cross-presentation of antigen delivered as an IC was shown in this study and a follow-up study to be dependent upon the common γ-chain and to depend upon both proteasomal processing of the antigen and peptide transport by TAP1–TAP2 [87, 88]. While DC were highly efficient at transferring IC-delivered antigen into the cytosol and inducing subsequent CD8+ T cell activation, similarly treated macrophages, which also express high levels of FcγR, retained protein within vesicles expressing high levels of the acid protease, cathepsin D, and failed to prime CD8+ T cells. This finding is supported by the observation that ligation of identical FcγR in DC and macrophages leads to differential intracellular signaling [122, 123]. Thus, while FcγR-binding by IgG IC is critical for initial antigen uptake, it is not sufficient to drive cross-presentation in the absence of an intracellular environment that is conducive to appropriate antigen degradation.

Nonetheless, the ability of FcγR to efficiently capture and internalize IgG-complexed antigens exerts potent effects on the ability of a given cell to cross-present. This point was emphasized by a study looking specifically at in vivo cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigen by CD8+ or CD8− DC subsets expressing equivalent levels of FcγR. While the former were found to cross-present IC-delivered ovalbumin (OVA) in either the presence or absence of functional FcγR, consistent with the known facility of this DC subset to cross-present soluble antigen, loss of FcγR function via deletion of the common γ-chain abrogated the ability of CD8− DC to cross-present IgG-complexed OVA [124]. Perhaps even more convincing is that transfection of a non-professional APC epithelial cell coexpressing H2-Kb with FcγRIIa, which is capable of signaling in the absence of the common γ-chain, successfully conferred cross-presenting ability upon these cells when the antigen was delivered as an IgG IC [97, 125]. Indeed, the initial study describing FcγR-mediated cross-presentation demonstrated that antigen delivered as an IgG IC was cross-presented with 3–4 orders of magnitude greater efficiency than the same antigen delivered in soluble form [87]. However, it is not simply the presence of FcγR on APC subsets but rather the relative proportion of activating versus inhibitory FcγR that may alter the cross-presenting capacity of the cell. While it is abundantly clear that engagement of the inhibitory FcγRIIb receptor by IgG IC is inhibitory towards cross-presentation and that an over-abundance of this receptor in pDC may account for their poor capacity to cross-present, the relative contribution of the various activating FcγR remains controversial [126–128]. While some groups have shown in vivo that equivalent levels of CD8+ T cell activation are achieved upon administration of IgG-complexed OVA in WT, FcγRI/FcγRIII−/− and FcγRI/FcγRII/FcγRIII−/− mice, other groups have demonstrated that ligation of FcγRIII with multimeric IC leads to more efficient cross-presentation than ligation of FcγRI [121, 129]. The latter is perhaps not surprising given that different intracellular signaling cascades have been documented upon IgG IC ligation of FcγRI versus FcγRIII and that these affect both the trafficking of downstream mediators through the endosomal compartments and the differential induction of cytokine secretion [130]. While the details of how each FcγR contributes to cross-presentation are complex, as outlined in Table 1, the emerging consensus is that ligation of activating FcγR by IgG-complexed antigen and the subsequent downstream activation of SYK are critical steps to enabling cross-presentation in some cell types and to boosting the cross-presentation capacity of other cell types [131].

Table 1.

Contribution of known IgG receptors to cross-presentation of IgG IC

| IgG receptor | Cell localization | Effect on cross-presentation | Cell type | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FcγR | Plasma membrane | + | [85, 86, 122, 133, 134] | |

| m/hFcγRI | Plasma membrane | + | CD8+ DC, CD8−CD11b+ DC, pDC | [119, 129, 136] |

| m/hFcγRIIa | Plasma membrane | + | CD8+ DC, CD8−CD11b+ DC, pDC | [119, 123, 129] |

| mFcγRIIb | Plasma membrane | – | CD8+ DC, CD8−CD11b+ DC, pDC | [124, 126] |

| m/hFcγRIII | Plasma membrane | + | CD8+ DC and CD8−CD11b+ DC | [119, 127, 129] |

| mFcγRIV | Plasma membrane | ? | ? | |

| mFcRn | Endolysomal vesicles | + | CD8−CD11b+ DC | [26] |

An important consideration raised by this knowledge is the fact that a wide variety of factors known to modulate surface expression levels or function of FcγR in DC will also affect the ability of these cells to cross-present complexed antigens. Whereas IL-4 is known to increase expression of the inhibitory FcγRIIb receptor and downregulate expression of activating FcγR, exposure of cells to IFNγ has the opposite effect [132]. Exposure of monocytes and macrophages to low doses of galectin-1, a carbohydrate-binding protein, not only increases expression of FcγRI but also increases the rate of FcγRI-dependent phagocytosis by inducing the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 [133]. Interaction of periplakin with the cytoplasmic domain of FcγRI has also been shown to increase the ability of this FcγR to bind to and endocytose IgG-complexed antigen and also to increase the resulting stimulation of CD4+ T cells [134]. Additionally, at least two complement proteins, C3 and C1q, have been documented to enhance the cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigens although whether FcγR are required for this modulation remains unresolved [135, 136]. An additional layer of complexity to be considered is the nature of the antigen contained within the immune complex, particularly if this contains ligands for additional PRR that might be triggered during or subsequent to FcγR-mediated internalization. Specifically, the TLR9 activating ligand CpG has been found to stimulate DC cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigen by FcγRI but to inhibit FcγRIIa-driven antigen presentation by pDC [137, 138]. While the effect of other TLR ligands specifically on the cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigen remain unexplored, ligation of many other TLR ligands, including TLR2, TLR7, TLR9, are known to affect cross-presentation and could thus alter how IgG-bound antigen is processed [64, 67, 139–141].

Despite such potentially mitigating variables, it is clear that uptake of IgG-complexed antigens enhances cross-presentation in the majority of cells. The importance of the initial uptake event in determining the eventual fate of an antigen has been clearly documented, particularly as it pertains to receptor-mediated endocytosis or phagocytosis by molecules such as FcγR [40, 52]. Critically, however, the ability of cells highly enabled for cross-presentation, such as CD8+ DC, cannot be explained by differential antigen capture and different DC subsets (CD11c+ DC vs. Langerhans cells) which take up identical antigen in different manners are able to cross-present antigen with equivalent efficiency [42, 142]. While FcγR are highly efficient at binding IgG at the neutral pH levels found at the cell surface and in driving the subsequent internalization of IgG IC, FcγR–IgG binding is increasingly impaired as pH drops into the acidic range typical of endolysosomal compartments [28]. While this may not affect the ability of FcγR to contribute to cross-presentation of antigen in CD8+ DC, where a near-neutral endosomal pH is maintained, it is unlikely that FcγR can contribute to active intracellular routing of IgG IC in most other subsets of DC as well as in monocytes and macrophages. While these latter cell types have not been described as efficient cross-presenters of soluble antigen, they are widely known to be capable of presentation of exogenous antigens on MHC class II molecules in a process that is enhanced by IgG complexing of the ligand [68, 143, 144]. Given that such IC would not be expected to be actively trafficked by FcγR within these cells, it is vitally important to consider the contribution of receptor-mediated intracellular IgG trafficking in all cells where antibody has been shown to enhance antigen presentation.

Receptor-mediated intracellular trafficking of IgG IC optimizes cross-presentation

Receptor-mediated intracellular IgG trafficking was first described in epithelial cells, where FcRn was demonstrated to be capable of bidirectionally translocating IgG and IgG IC across a polarized cell with distinct apical and basal membrane surfaces in both in vitro model systems and in vivo in the intestines [107, 145, 146]. This has subsequently been confirmed in other polarized epithelia and is a common property of such cell types when FcRn is expressed [147–154]. Several details regarding the biology of FcRn strongly suggested that it might be an attractive candidate as an intracellular IgG receptor within DC capable of driving FcγR-internalized IC towards cross-presentation. Chief among these were its lifelong expression in both human and murine DC, its predominantly intracellular distribution and its ability to bind IgG in the acidic pH range typically found within the endosomal system of APC [47, 155, 156]. Furthermore, FcRn is known to increase the efficiency of MHC class II presentation of IgG-complexed antigens above that for soluble antigen in both DC and macrophages, thereby confirming its ability to intracellularly route IgG IC within APC [9, 157]. A series of both in vitro and in vivo data generated using either FcRn-deficient DC or genetically altered IgG incapable of FcRn binding clearly indicated that FcRn ligation greatly increased cross-presentation efficiency for IgG IC-containing antigen of various sizes [28]. FcRn-driven augmentation of cross-presentation was strongest at very low concentrations of antigen and was strictly dependent on initial IgG IC internalization by FcγR based upon studies which utilized mutation N297A as a means to disable this type of IgG binding [28]. In fact, at high antigen doses in the range at which soluble antigen are efficiently cross-presented, FcRn did not contribute to cross-presentation by either DC or macrophages [28, 43, 44, 124, 157, 158]. Critically, FcRn-mediated enhancement was predominantly seen in CD8−CD11b+ DC, which are not typically known to cross-present soluble antigen but in which the pH of the endolysosomal system has been demonstrated to reach acidic conditions permissive for FcRn–IgG binding but inhibitory for FcγR–IgG binding [28]. Indeed, while FcRn–IgG binding remained stable at pH 6.5–5.0, the pH of the phagosomal compartments in which FcRn localized was shown to stabilize at approximately pH 6.0 thereby enabling FcRn to remain bound to IgG IC in these compartments for extended periods of time [28]. This is in stark contrast to the endosomal pH conditions of CD8+CD11b− DC which are strictly buffered at approximately pH 7.0 by the actions of the NADPH oxidase NOX2 and do not decrease to levels in which FcRn is capable of IgG binding [43, 47].

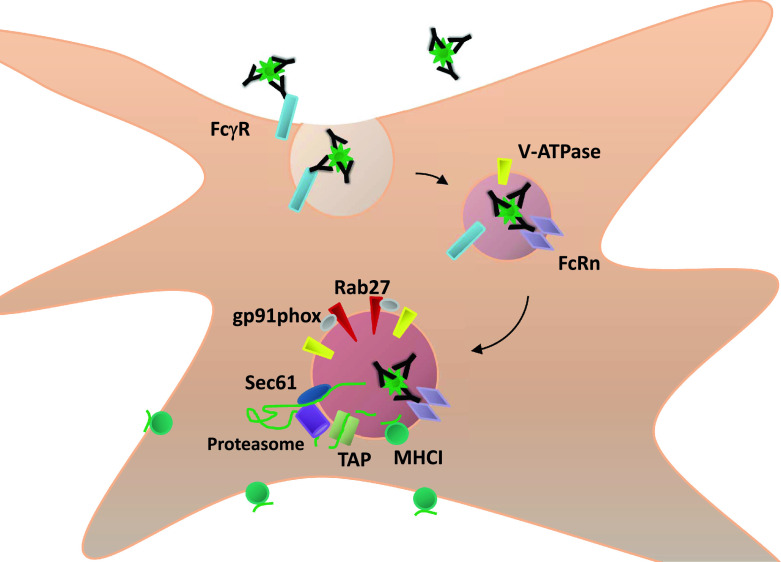

Unexpectedly, FcRn ligation of IgG IC was found to participate not only in the acidification of the IC-containing phagosome but also in the regulation of the oxidative environment within this compartment since V-ATPase, Rab27a and gp91phox were all found to be enriched in the vesicles where FcRn was cross-linked [28]. The mechanism of this enrichment remains unknown and could involve either the active recruitment of these molecules, regulation of the fusion and/or maturation of different endocytic compartments, or the active trafficking of IgG IC into a specialized intracellular compartment. Consistent with all previous reports of FcγR-mediated cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigen, antigenic degradation of FcRn-trafficked IC was shown to involve typical ER proteins, to depend upon export of the antigen from the initial compartment into the cytosol and to require proteasomal processing [58, 88, 159]. The observed prolonged retention of FcRn-bound IgG IC within the intracellular compartment is also consistent with another published study demonstrating that IgG complexed antigens are stored for extended periods of time within intracellular vesicles capable of acting as antigen reservoirs for continuous loading onto MHC class I [160]. While this observation may at first seem at odds with the need for proteasomal processing of the IgG-delivered antigen, a plausible explanation is that FcRn-ligation of IgG IC permits a slower and more controlled antigenic degradation in a manner akin to that which is necessary for epitope preservation and efficient cross-presentation of soluble antigen by CD8+ DC [19, 24, 28, 43]. As outlined in Figure 1, the combined effects of efficient FcγR-mediated internalization and FcRn-directed trafficking within DC subsets not typically conducive to cross-presentation of soluble antigen thus transform these cells into sensitive and potent primers of cytotoxic CD8+ T cell immunity.

Fig. 1.

IgG immune complexes are directed into a cross-presentation processing pathway via sequential interaction with IgG receptors. IgG-containing immune complexes (IgG IC) are bound by FcγR on the surface of DC, leading to their initial internalization. In the acidic environment of the endosomal system, generated at least in part by the actions of V-ATPase, the IgG IC is released from FcγR but tightly bound by FcRn, which only binds to IgG at pH ≤6.0. By an as yet unknown FcRn-dependent mechanism, the IgG IC is shuttled into a vesicular compartment equipped with oxidative machinery (gp91phox), delivered in a Rab27a-dependent manner, antigen exporting molecules (Sec61), peptide importing molecules (TAP1/2) and MHC class I itself. Subsequent to cytoplasmic proteasomal processing, epitopes from the antigen initially imported by the IgG IC are loaded onto MHC class I and trafficked to the cell membrane where they may engage CD8+ T cells, thereby priming cytotoxic T cell-mediated immunity

Implications of the cross-presentation of IgG IC in health and disease

The implications of IgG’s ability to augment the cross-presentation of opsonized antigens and drive the subsequent priming of CD8+ T cell responses should not be underestimated. Cross-priming of IgG-complexed self-antigens has been shown to contribute to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases such as diabetes, where engagement of the inhibitory FcγRIIb by IgG IC contributes to regulating development of both systemic and oral tolerance by a mechanism which at least partly involves suppression of cross-presentation by simultaneously ligated activating FcγR [126, 128]. Failure of this regulatory system can lead to loss of tolerance to self-antigens, as evidenced by the fact that administration of anti-OVA IgG to mice whose pancreatic β cells express OVA leads to the development of CD8+ T cell driven diabetes [161]. Furthermore, IgG IC have been shown to drive colitis in an FcRn-dependent manner and the recent identification of a potential pathogenic role for CD8+ T cells in this disease is likely attributable at least in part to activation of CD8+ T cells by cross-presentation of IgG-complexed bacteria or bacterial ligands [28, 115, 162]. Indeed, it is likely that the modest ameliorative effect of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment when administered to patients with IgG-mediated diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) functions at least partly through inhibition of the cross-presentation of IgG-complexed autoantigens [115, 163–167]. Likewise, inhibition of SYK signaling downstream of FcγR activation in DC has been shown to protect mice against the development of autoimmune diabetes, the onset of which was previously demonstrated to depend upon IgG-mediated presentation of self-antigen [161, 168]. Conversely, IgG-mediated cross-presentation is protective towards Salmonella infections and can be presumed to contribute to the defense against other pathogenic diseases and viruses [69, 169]. Together, these studies highlight the fact that the cross-presentation of IgG IC occurs under physiological contexts for both IgG bound soluble antigens, such as proteinaceous self-antigens [126, 128, 161], as well as IgG bound particulate antigens, such as microbes [28, 69, 115, 162, 169]. Further, they emphasize the importance of IgG IC-induced cross-priming in both homeostatic and inflammatory immunity. Indeed, it is likely that Fc-receptor-mediated cross-presentation is a central component of immune responses against a wide range of pathogens, particularly intracellular microbes, and aberrant self-cells, such as cancers. While details of the specific contribution of the individual Fc receptors to this process remain to be fully explored, it can be expected that perturbations in either IgG IC uptake or intracellular routing would disrupt cross-presentation and impair the host’s ability to respond in these circumstances.

Perhaps the aspect of IgG IC-driven cross-presentation which has generated the most attention is its therapeutic applications—namely the potential to use low levels of IgG complexed antigen to induce potent cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses against bacterial, viral and tumor antigens. At least two separate studies have demonstrated the importance of anti-viral IgG in driving cross-presentation-mediated protection against immunodeficiency viruses. In the first of these, anti-p55-Gag IgG enhanced the presentation of SIV Gag on MHC class I and improved the generation of specific cytotoxic T cell precursors in a process requiring proteasomal degradation [170]. In the second study, sublingual vaccination with HIV-1 proteins and an adjuvant led to the development of both antigen-specific IgG and CD8+ T cells, the latter of which accumulate in the vaginal mucosa [171]. Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated the successful generation of anti-tumor CD8+ T cell immunity using vaccines composed of either whole, inactivated or apoptotic tumor cells opsonized with IgG and thereby efficiently targeting tumor antigens for presentation on MHC class I molecules without the limitation of needing to first define individual tumor antigens [172–175]. While this technique is not without limitations, it highlights the potential benefits which can be gained from a better understanding of the cross-presentation of IgG-complexed antigens and which will allow for more effective therapeutic manipulations of this potent system.

Cross-presentation by other immunoglobulin receptors

Given the potency of IgG IC-mediated cross-presentation and the prevalence of receptors for other immunoglobulin isotypes, determining whether these other Ig are also capable of driving antigen towards a cross-presented fate will be important to explore. For some isotypes, data already exists on their ability to stimulate CD4+ T cells and thus a precedent has been set for their ability to activate cell-mediated immunity. Specifically, IC formed with IgA and antigen have been shown to promote antigen loading onto MHC class II molecules in an FcαRI (CD89)-dependent manner which was enhanced by signaling from the common γ-chain [176, 177]. Similarly, IgE is known to be able to drive antigen internalization in a manner which drives the activation of CD4+ T cells [178–180]. Recently, an insightful review has presented the as yet unproven idea that cross-presentation of antigen bound to IgE and internalized via either or both FcεRI or FcεRII is the mechanism by which IgE-driven responses can be linked to CD8+ T cell activation [181]. Furthermore, targeting antigen for receptor-mediated uptake on B cells via surface-expressed IgM can introduce the antigen into a cross-presentation pathway in B cells [182]. Perhaps most importantly of all is the consideration that immune complexes are likely to simultaneously contain multiple different Ig isotypes such that multiple Fc receptors would be triggered upon IC binding and uptake. Indeed, at least one study has demonstrated that both FcεRI and FcγR contribute to the development of atopic dermatitis, although each receptor was found to drive a different aspect of the pathology [183]. Thus, in addition to investigating the ability of different Ig and their receptors to singularly drive cross-presentation, a true understanding of the impact of Ig in both physiological and pathophysiological situations will require an investigation of the cooperative effects of the different Ig–receptor pairs when simultaneously ligated within a cell.

Conclusions

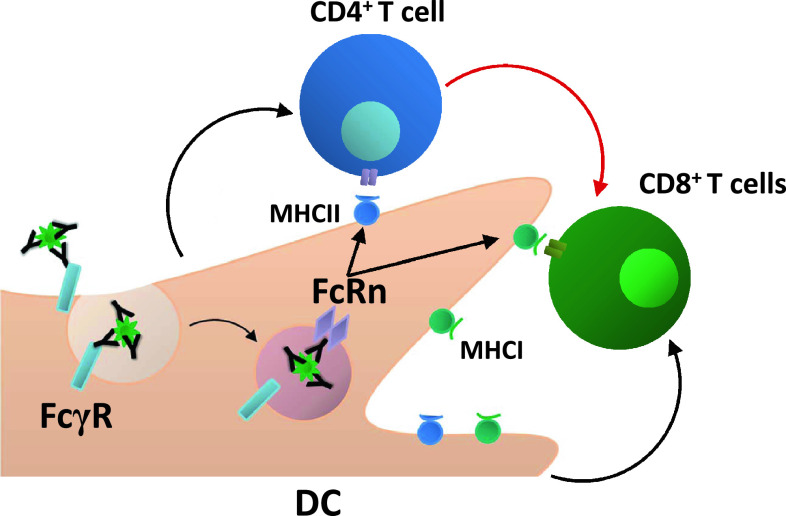

The complexity of the vertebrate immune system is such that coordination between its different branches is required in order to optimize protection against potential pathogens. Due to their dual nature which combines the ability to specifically bind unique ligands with a conserved Fc region, immunoglobulins are capable of bridging a gap between innate and adaptive immunity. This is particularly the case for IgG, an abundant Ig for which various different receptors exist over a distribution of subcellular localizations. When the Fc region of IgG within an immune complex is bound by their specific receptors on DC, the antigen is delivered into an intracellular pathway allowing for efficient processing and subsequent presentation of epitopes specific for the unique antigen. Thus, an antigen-specific T cell response can be generated by a cell entirely lacking a specific receptor for the antigen. A final aspect that deserves mention is that since IgG-containing immune complexes can potently deliver antigen to both MHC class I and MHC class II antigen presentation pathways in DC, the DC which contains both internalization (FcγR) and routing (FcRn) receptors is able to assume the critically central role of a single site for CD4+ and CD8+ T cell docking that allows for optimal priming of both helper and cytotoxic responses; the latter of which depends upon T cell help from CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2) [20–22]. While we have only begun to understand the mechanisms behind IgG-mediated cross-presentation enhancement and how it compares to that of soluble antigen, the exquisite sensitivity demonstrated for this system makes it an attractive target for further study. Not only will this generate a better understanding of how this process naturally confers immunological protection under conditions of homeostasis or infection but also of how it can be therapeutically manipulated to target and resolve a multitude of pathological conditions.

Fig. 2.

Delivery of antigen within an IgG IC leads to effective priming of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by the same DC. FcγR and FcRn cooperate to deliver IgG IC into antigen processing pathways conducive to the generation of epitopes for loading onto both MHC class I and MHC class II. This enables activation of CD4+ T cells, which, in turn, provide the additional stimuli required for efficient activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses

Acknowledgments

K.B. was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. T.R. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (RA 2040/1-1). E.F is supported by NIH AI075037. W.I.L. is supported by NIH DK084424. R.S.B is supported by NIH DK053056, DK053162, DK088199 and DK044319. W.I.L. and R.S.B. are also supported by the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center (NIH P30DK034854). The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerutti A, Puga I, Cols M. Innate control of B cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(5):202–211. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He B, Xu W, Santini PA, Polydorides AD, Chiu A, Estrella J, Shan M, Chadburn A, Villanacci V, Plebani A, Knowles DM, Rescigno M, Cerutti A. Intestinal bacteria trigger T cell-independent immunoglobulin A2 class switching by inducing epithelial-cell secretion of the cytokine APRIL. Immunity. 2007;26(6):812–826. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Antibody-mediated regulation of cellular immunity and the inflammatory response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24(9):474–478. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00228-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodewald R, Kraehenbuhl JP. Receptor-mediated transport of IgG. J Cell Biol. 1984;99(1):159s–164s. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.159s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mi W, Wanjie S, Lo ST, Gan Z, Pickl-Herk B, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Targeting the neonatal fc receptor for antigen delivery using engineered fc fragments. J Immunol. 2008;181(11):7550–7561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ober RJ, Martinez C, Lai X, Zhou J, Ward ES. Exocytosis of IgG as mediated by the receptor, FcRn: an analysis at the single-molecule level. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(30):11076–11081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402970101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ober RJ, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ward ES. Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor. FcRn. J Immunol. 2004;172(4):2021–2029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiao SW, Kobayashi K, Johansen FE, Sollid LM, Andersen JT, Milford E, Roopenian DC, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(27):9337–9342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akilesh S, Christianson GJ, Roopenian DC, Shaw AS. Neonatal FcR expression in bone marrow-derived cells functions to protect serum IgG from catabolism. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4580–4588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amigorena S, Lankar D, Briken V, Gapin L, Viguier M, Bonnerot C. Type II and III receptors for immunoglobulin G (IgG) control the presentation of different T cell epitopes from single IgG-complexed antigens. J Exp Med. 1998;187(4):505–515. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simitsek PD, Campbell DG, Lanzavecchia A, Fairweather N, Watts C. Modulation of antigen processing by bound antibodies can boost or suppress class II major histocompatibility complex presentation of different T cell determinants. J Exp Med. 1995;181(6):1957–1963. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrington RA, Pozdnyakova O, Zafari MR, Benjamin CD, Carroll MC. B lymphocyte memory. J Exp Med. 2002;196(9):1189–1200. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Meckel T, Tolar P, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. Antigen affinity discrimination is an intrinsic function of the B cell receptor. J Exp Med. 2010;207(5):1095–1111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macardle PJ, Mardell C, Bailey S, Wheatland L, Ho A, Jessup C, Roberton DM, Zola H. FcγRIIb expression on human germinal center B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(12):3736–3744. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3736::AID-IMMU3736>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bevan MJ. Cross-priming for a secondary cytotoxic response to minor H antigens with H-2 congenic cells which do not cross-react in the cytotoxic assay. J Exp Med. 1976;143(5):1283–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.5.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bevan MJ. Minor H antigens introduced on H-2 different stimulating cells cross-react at the cytotoxic T cell level during in vivo priming. J Immunol. 1976;117(6):2233–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rock KL, Gamble S, Rothstein L. Presentation of exogenous antigen with class I major histocompatibility complex molecules. Science. 1990;249(4971):918–921. doi: 10.1126/science.2392683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreer C, Rauen J, Zehner M, Burgdorf S. Cross-presentation: how to get there—or how to get the ER. Front Immunol. 2012;2:87. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumamoto Y, Mattei LM, Sellers S, Payne GW, Iwasaki A. CD4+ T cells support cytotoxic T lymphocyte priming by controlling lymph node input. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(21):8749–8754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100567108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science. 2003;300(5617):337. doi: 10.1126/science.1082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiser M, Wieland A, Plachter B, Mertens T, Greiner J, Schirmbeck R. The immunodominant CD8 T cell response to the human cytomegalovirus tegument phosphoprotein pp 65(495–503) epitope critically depends on CD4 T cell help in vaccinated HLA-A*0201 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2172–2180. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ackerman AL, Cresswell P. Cellular mechanisms governing cross-presentation of exogenous antigens. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(7):678–684. doi: 10.1038/ni1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amigorena S, Savina A. Intracellular mechanisms of antigen cross presentation in dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(1):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Idoyaga J, Lubkin A, Fiorese C, Lahoud MH, Caminschi I, Huang Y, Rodriguez A, Clausen BE, Park CG, Trumpfheller C, Steinman RM. Comparable T helper 1 (Th1) and CD8 T-cell immunity by targeting HIV gag p24 to CD8 dendritic cells within antibodies to Langerin, DEC205, and Clec9A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(6):2384–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019547108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bozzacco L, Trumpfheller C, Siegal FP, Mehandru S, Markowitz M, Carrington M, Nussenzweig MC, Piperno AG, Steinman RM. DEC-205 receptor on dendritic cells mediates presentation of HIV gag protein to CD8+ T cells in a spectrum of human MHC I haplotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(4):1289–1294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610383104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheong C, Choi J-H, Vitale L, He L-Z, Trumpfheller C, Bozzacco L, Do Y, Nchinda G, Park SH, Dandamudi DB, Shrestha E, Pack M, Lee H-W, Keler T, Steinman RM, Park CG. Improved cellular and humoral immune responses in vivo following targeting of HIV Gag to dendritic cells within human anti-human DEC205 monoclonal antibody. Blood. 2010;116(19):3828–3838. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker K, Qiao S-W, Kuo TT, Aveson VG, Platzer B, Andersen J-T, Sandlie I, Chen Z, de Haar C, Lencer WI, Fiebiger E, Blumberg RS. Neonatal Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) regulates cross-presentation of IgG immune complexes by CD8−CD11b+dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(24):9927–9932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019037108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amigorena S, Bonnerot C. Fc receptors for IgG and antigen presentation on MHC class I and class II molecules. Semin Immunol. 1999;11(6):385–390. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segura E, Villadangos JA. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells in vivo. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(1):105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P. Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(7):543–555. doi: 10.1038/nri2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pulendran B, Tang H, Denning TL. Division of labor, plasticity, and crosstalk between dendritic cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelsall BL, Leon F. Involvement of intestinal dendritic cells in oral tolerance, immunity to pathogens, and inflammatory bowel disease. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:132–148. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelsall B. Recent progress in understanding the phenotype and function of intestinal dendritic cells and macrophages. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(6):460–469. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Hardt W-D, Shakhar G, Jung S. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31(3):502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, Greenshtein L, Gildor B, Margalit R, Kalchenko V, Geissmann F, Jung S. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(1):171–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heath WR, Carbone FR. Dendritic cell subsets in primary and secondary T cell responses at body surfaces. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(12):1237–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, Calderon B, Schraml BU, Unanue ER, Diamond MS, Schreiber RD, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322(5904):1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jongbloed SL, Kassianos AJ, McDonald KJ, Clark GJ, Ju X, Angel CE, Chen C-JJ, Dunbar PR, Wadley RB, Jeet V, Vulink AJE, Hart DNJ, Radford KJ. Human CD141+ (BDCA-3)+ dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. J Exp Med. 2010;207(6):1247–1260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamphorst AO, Guermonprez P, Dudziak D, Nussenzweig MC. Route of antigen uptake differentially impacts presentation by dendritic cells and activated monocytes. J Immunol. 2010;185(6):3426–3435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee H-W, Park CG, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315(5808):107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnorrer P, Behrens GM, Wilson NS, Pooley JL, Smith CM, El-Sukkari D, Davey G, Kupresanin F, Li M, Maraskovsky E, Belz GT, Carbone FR, Shortman K, Heath WR, Villadangos JA. The dominant role of CD8+ dendritic cells in cross-presentation is not dictated by antigen capture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(28):10729–10734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601956103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savina A, Jancic C, Hugues S, Guermonprez P, Vargas P, Moura IC, Lennon-Duménil A-M, Seabra MC, Raposo G, Amigorena S. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2006;126(1):205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jancic C, Savina A, Wasmeier C, Tolmachova T, El-Benna J, Dang PM-C, Pascolo S, Gougerot-Pocidalo M-A, Raposo G, Seabra MC, Amigorena S. Rab27a regulates phagosomal pH and NADPH oxidase recruitment to dendritic cell phagosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(4):367–378. doi: 10.1038/ncb1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jusforgues-Saklani H, Uhl M, Blachere N, Lemaitre F, Lantz O, Bousso P, Braun D, Moon JJ, Albert ML. Antigen persistence is required for dendritic cell licensing and CD8+ T cell cross-priming. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3067–3076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savina A, Amigorena S. Phagocytosis and antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;219(1):143–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell DG. New ways to arrest phagosome maturation. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/ncb0407-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trombetta ES, Ebersold M, Garrett W, Pypaert M, Mellman I. Activation of lysosomal function during dendritic cell maturation. Science. 2003;299(5611):1400–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delamarre L, Pack M, Chang H, Mellman I, Trombetta ES. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science. 2005;307(5715):1630–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1108003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cebrian I, Visentin G, Blanchard N, Jouve M, Bobard A, Moita C, Enninga J, Moita Luis F, Amigorena S, Savina A. Sec22b regulates phagosomal maturation and antigen crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2011;147(6):1355–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Savina A, Peres A, Cebrian I, Carmo N, Moita C, Hacohen N, Moita LF, Amigorena S. The small GTPase Rac2 controls phagosomal alkalinization and antigen crosspresentation selectively in CD8+ dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;30(4):544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belizaire R, Unanue ER. Targeting proteins to distinct subcellular compartments reveals unique requirements for MHC class I and II presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(41):17463–17468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908583106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen L, Sigal LJ, Boes M, Rock KL. Important role of cathepsin S in generating peptides for TAP-independent MHC class I crosspresentation in vivo. Immunity. 2004;21(2):155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rock KL, Farfan-Arribas DJ, Shen L. Proteases in MHC class I presentation and cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):9–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Basha G, Lizee G, Reinicke AT, Seipp RP, Omilusik KD, Jefferies WA. MHC class I endosomal and lysosomal trafficking coincides with exogenous antigen loading in dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(9):e3247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saveanu L, Carroll O, Weimershaus M, Guermonprez P, Firat E, Lindo V, Greer F, Davoust J, Kratzer R, Keller SR, Niedermann G, Endert P. IRAP identifies an endosomal compartment required for MHC class I cross-presentation. Science. 2009;325(5937):213–217. doi: 10.1126/science.1172845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Houde M, Bertholet S, Gagnon E, Brunet S, Goyette G, Laplante A, Princiotta MF, Thibault P, Sacks D, Desjardins M. Phagosomes are competent organelles for antigen cross-presentation. Nature. 2003;425:402. doi: 10.1038/nature01912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guermonprez P, Saveanu L, Kleijmeer M, Davoust J, van Endert P, Amigorena S. ER-phagosome fusion defines an MHC class I cross-presentation compartment in dendritic cells. Nature. 2003;425(6956):397–402. doi: 10.1038/nature01911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merzougui N, Kratzer R, Saveanu L, van Endert P. A proteasome-dependent, TAP-independent pathway for cross-presentation of phagocytosed antigen. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(12):1257–1264. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Cresswell P. A role for the endoplasmic reticulum protein retrotranslocation machinery during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Immunity. 2006;25(4):607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ackerman AL, Kyritsis C, Tampe R, Cresswell P. Early phagosomes in dendritic cells form a cellular compartment sufficient for cross presentation of exogenous antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(22):12889–12894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735556100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cresswell P, Ackerman AL, Giodini A, Peaper DR, Wearsch PA. Mechanisms of MHC class I-restricted antigen processing and cross-presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207(1):145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ito T, Inaba M, Inaba K, Toki J, Sogo S, Iguchi T, Adachi Y, Yamaguchi K, Amakawa R, Valladeau J, Saeland S, Fukuhara S, Ikehara S. A CD1a+/CD11c+ subset of human blood dendritic cells is a direct precursor of Langerhans cells. J Immunol. 1999;163(3):1409–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salio M, Palmowski MJ, Atzberger A, Hermans IF, Cerundolo V. CpG-matured murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells are capable of in vivo priming of functional CD8 T cell responses to endogenous but not exogenous antigens. J Exp Med. 2004;199(4):567–579. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mouries J, Moron G, Schlecht G, Escriou N, Dadaglio G, Leclerc C. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells efficiently cross-prime naive T cells in vivo after TLR activation. Blood. 2008;112(9):3713–3722. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoeffel G, Ripoche AC, Matheoud D, Nascimbeni M, Escriou N, Lebon P, Heshmati F, Guillet JG, Gannage M, Caillat-Zucman S, Casartelli N, Schwartz O, De la Salle H, Hanau D, Hosmalin A, Maranon C. Antigen crosspresentation by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity. 2007;27(3):481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nierkens S, den Brok MH, Garcia Z, Togher S, Wagenaars J, Wassink M, Boon L, Ruers TJ, Figdor CG, Schoenberger SP, Adema GJ, Janssen EM. Immune adjuvant efficacy of CpG oligonucleotide in cancer treatment is founded specifically upon TLR9 function in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(20):6428–6437. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Segura E, Albiston AL, Wicks IP, Chai SY, Villadangos JA. Different cross-presentation pathways in steady-state and inflammatory dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(48):20377–20381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910295106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tobar JA, Gonzalez PA, Kalergis AM. Salmonella escape from antigen presentation can be overcome by targeting bacteria to Fc{gamma} receptors on dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(6):4058–4065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pfeifer JD, Wick MJ, Roberts RL, Findlay K, Normark SJ, Harding CV. Phagocytic processing of bacterial antigens for class I MHC presentation to T cells. Nature. 1993;361(6410):359–362. doi: 10.1038/361359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Svensson M, Wick MJ. Classical MHC class I peptide presentation of a bacterial fusion protein by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(1):180–188. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199901)29:01<180::AID-IMMU180>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Palmowski MJ, Gileadi U, Salio M, Gallimore A, Millrain M, James E, Addey C, Scott D, Dyson J, Simpson E, Cerundolo V. Role of immunoproteasomes in cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2006;177(2):983–990. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lautscham G, Haigh T, Mayrhofer S, Taylor G, Croom-Carter D, Leese A, Gadola S, Cerundolo V, Rickinson A, Blake N. Identification of a TAP-independent, immunoproteasome-dependent CD8+ T-cell epitope in Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2. J Virol. 2003;77(4):2757–2761. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2757-2761.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hutchinson S, Sims S, O’Hara G, Silk J, Gileadi U, Cerundolo V, Klenerman P. A dominant role for the immunoproteasome in CD8+ T cell responses to murine cytomegalovirus. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e14646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tu L, Moriya C, Imai T, Ishida H, Tetsutani K, Duan X, Murata S, Tanaka K, Shimokawa C, Hisaeda H, Himeno K. Critical role for the immunoproteasome subunit LMP7 in the resistance of mice to Toxoplasma gondii infection. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(12):3385–3394. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burgdorf S, Lukacs-Kornek V, Kurts C. The mannose receptor mediates uptake of soluble but not of cell-associated antigen for cross-presentation. J Immunol. 2006;176(11):6770–6776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burgdorf S, Kautz A, Bohnert V, Knolle PA, Kurts C. Distinct pathways of antigen uptake and intracellular routing in CD4 and CD8 T cell activation. Science. 2007;316(5824):612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1137971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burgdorf S, Schuette V, Semmling V, Hochheiser K, Lukacs-Kornek V, Knolle PA, Kurts C. Steady-state cross-presentation of OVA is mannose receptor-dependent but inhibitable by collagen fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(13):E48–E49. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000598107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zehner M, Chasan AI, Schuette V, Embgenbroich M, Quast T, Kolanus W, Burgdorf S. Mannose receptor polyubiquitination regulates endosomal recruitment of p97 and cytosolic antigen translocation for cross-presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(24):9933–9938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102397108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kratzer R, Mauvais F-X, Burgevin A, Barilleau E, van Endert P. Fusion proteins for versatile antigen targeting to cell-surface receptors reveal differential capacity to prime immune responses. J Immunol. 2010;184(12):6855–6864. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsuji T, Matsuzaki J, Kelly MP, Ramakrishna V, Vitale L, He L-Z, Keler T, Odunsi K, Old LJ, Ritter G, Gnjatic S. Antibody-targeted NY-ESO-1 to mannose receptor or DEC-205 in vitro elicits dual human CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses with broad antigen specificity. J Immunol. 2010;186(2):1218–1227. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bonifaz LC, Bonnyay DP, Charalambous A, Darguste DI, Fujii S, Soares H, Brimnes MK, Moltedo B, Moran TM, Steinman RM. In vivo targeting of antigens to maturing dendritic cells via the DEC-205 receptor improves T cell vaccination. J Exp Med. 2004;199(6):815–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vremec D, Shortman K. Dendritic cell subtypes in mouse lymphoid organs: cross-correlation of surface markers, changes with incubation, and differences among thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1997;159(2):565–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.del Hoyo GM, Martin P, Arias CF, Martin AR, Ardavin C. CD8alpha+ dendritic cells originate from the CD8alpha- dendritic cell subset by a maturation process involving CD8alpha, DEC-205, and CD24 up-regulation. Blood. 2002;99(3):999–1004. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.3.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bonifaz L, Bonnyay D, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8 + T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2002;196(12):1627–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Amigorena S, Bonnerot C. Fc receptor signaling and trafficking: a connection for antigen processing. Immunol Rev. 1999;172:279–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1999.tb01372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Regnault A, Lankar D, Lacabanne V, Rodriguez A, Thery C, Rescigno M, Saito T, Verbeek S, Bonnerot C, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Amigorena S. Fcgamma receptor-mediated induction of dendritic cell maturation and major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen presentation after immune complex internalization. J Exp Med. 1999;189(2):371–380. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rodriguez A, Regnault A, Kleijmeer M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Amigorena S. Selective transport of internalized antigens to the cytosol for MHC class I presentation in dendritic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(6):362–368. doi: 10.1038/14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Antibody-mediated modulation of immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2010;236(1):265–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fc-gamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kiener PA, Rankin BM, Burkhardt AL, Schieven GL, Gilliland LK, Rowley RB, Bolen JB, Ledbetter JA. Cross-linking of Fc gamma receptor I (Fc gamma RI) and receptor II (Fc gamma RII) on monocytic cells activates a signal transduction pathway common to both Fc receptors that involves the stimulation of p72 Syk protein tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(32):24442–24448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kurosaki T, Johnson SA, Pao L, Sada K, Yamamura H, Cambier JC. Role of the Syk autophosphorylation site and SH2 domains in B cell antigen receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 1995;182(6):1815–1823. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ghazizadeh S, Bolen JB, Fleit HB. Physical and functional association of Src-related protein tyrosine kinases with Fc gamma RII in monocytic THP-1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(12):8878–8884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang AV, Scholl PR, Geha RS. Physical and functional association of the high affinity immunoglobulin G receptor (Fc gamma RI) with the kinases Hck and Lyn. J Exp Med. 1994;180(3):1165–1170. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang MM, Indik Z, Brass LF, Hoxie JA, Schreiber AD, Brugge JS. Activation of Fc gamma RII induces tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins including Fc gamma RII. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(8):5467–5473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Indik ZK, Park JG, Hunter S, Schreiber AD. The molecular dissection of Fc gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Blood. 1995;86(12):4389–4399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Indik ZK, Park J-G, Hunter S, Mantaring M, Schreiber AD. Molecular dissection of Fc-gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Immunol Lett. 1995;44(2–3):133–138. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mitchell MA, Huang MM, Chien P, Indik ZK, Pan XQ, Schreiber AD. Substitutions and deletions in the cytoplasmic domain of the phagocytic receptor Fc gamma RIIA: effect on receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and phagocytosis. Blood. 1994;84(6):1753–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Breunis WB, van Mirre E, Bruin M, Geissler J, de Boer M, Peters M, Roos D, de Haas M, Koene HR, Kuijpers TW. Copy number variation of the activating FCGR2C gene predisposes to idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2008;111(3):1029–1038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ono M, Bolland S, Tempst P, Ravetch JV. Role of the inositol phosphatase SHIP in negative regulation of the immune system by the receptor Fe[gamma]RIIB. Nature. 1996;383(6597):263–266. doi: 10.1038/383263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang W, Gordon M, Schultheis AM, Yang DY, Nagashima F, Azuma M, Chang H-M, Borucka E, Lurje G, Sherrod AE, Iqbal S, Groshen S, Lenz H-J. FCGR2A and FCGR3A polymorphisms associated with clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor-expressing metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with single-agent cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(24):3712–3718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Binstadt BA, Geha RS, Bonilla FA. IgG Fc receptor polymorphisms in human disease: implications for intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(4):697–703. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bournazos S, Woof JM, Hart SP, Dransfield I. Functional and clinical consequences of Fc receptor polymorphic and copy number variants. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157(2):244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bruhns P, Iannascoli B, England P, Mancardi DA, Fernandez N, Jorieux S, Daeron M. Specificity and affinity of human Fc-gamma receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood. 2009;113(16):3716–3725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Simister NE, Mostov KE. An Fc receptor structurally related to MHC class I antigens. Nature. 1989;337(6203):184–187. doi: 10.1038/337184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Simister NE, Rees AR. Isolation and characterization of an Fc receptor from neonatal rat small intestine. Eur J Immunol. 1985;15(7):733–738. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830150718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Claypool SM, Dickinson BL, Yoshida M, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Functional reconstitution of human FcRn in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells requires co-expressed human beta 2-microglobulin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(31):28038–28050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202367200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Baker K, Qiao SW, Kuo T, Kobayashi K, Yoshida M, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS. Immune and non-immune functions of the (not so) neonatal Fc receptor FcRn. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31(2):223–236. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0160-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]