Abstract

Objectives

To characterize the spectrum, symptoms, progression and effects of endocrine dysfunction on sinonasal disease in polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (PFD) and McCune-Albright Syndrome (MAS).

Study Design

Retrospective review.

Methods

A prospectively followed cohort of subjects with PFD/MAS underwent a comprehensive evaluation that included otolaryngologic and endocrine evaluation, and imaging studies. Head and facial CT scans were analyzed, and the degree of fibrous dysplasia (FD) was graded using a modified Lund-MacKay scale. Those followed for more than 4 years were analyzed for progression.

Results

A total of 106 patients meeting inclusion criteria were identified with craniofacial FD. A majority (92%) demonstrated sinonasal involvement. There were significant positive correlations between the sinonasal FD scale score and chronic congestion, hyposmia, growth hormone excess and hyperthyroidism (p < 0.05 for all). Significant correlations were not found for headache/facial pain or recurrent/chronic sinusitis. Thirty-one subjects met the criteria for longitudinal analysis (follow-up mean 6.3 years, range 4.4 – 9 years). Those demonstrating disease progression were significantly younger than those who did not (mean age = 11 vs. 25 years). Progression after age of 13 years was uncommon (n=3) and minimal. Concomitant endocrinopathy or bisphosphonate use did not have any significant effect on progression of disease.

Conclusion

Sinonasal involvement of fibrous dysplasia in PFD/MAS is common. Symptoms are usually few and mild, and disease progression occurs primarily in young subjects. Concomitant endocrinopathy is associated with disease severity, but not progression.

Keywords: Fibrous dysplasia, McCune Albright Syndrome, sinonasal

Introduction

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia (MFD), polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (PFD), and McCune-Albright Syndrome (MAS) are disease processes linked in their common etiology and represent a spectrum of phenotypic severity. MFD and PFD are characterized by fibro-dysplastic bone of one or more skeletal sites. Initially characterized by McCune and Albright1,2, MAS has been classically described as a triad of precocious puberty, café-au-lait spots, and PFD. The present day definition has been broadened to not only include precocious puberty, but other hyper-functioning endocrinopathies as well3,4. The once enigmatic etiology of these three disorders has been further elucidated with the discovery of a somatic mutation of the GNAS gene on chromosome 20q13, which leads to impaired GTPase activity in the protein Gsα, with altered cAMP signaling 5, and increased proliferation of the cells of the osteogenic lineage in the bone marrow 6,7. The degree of phenotypic severity depends on the migration and survival of the mutated cell during embryonic development 8,9.

While PFD and MAS are relatively uncommon entities, craniofacial fibrous dysplasia is frequently found in these patients and has been reported in the literature to occur in up to 50–100% of cases10. Many aspects of the craniofacial involvement have not been well-characterized, due in large part to the relative rarity of the disorders. The significance of sinonasal disease, in particular, is poorly understood. The body of the published literature is dominated by case reports and small case series that are limited, and provide only partial insight into the true nature of this aspect of FD. It is important to further define sinonasal FD so as to be able to accurately predict the course of the disease. Such knowledge enables more appropriate treatment and aids in determining which cases warrant aggressive surgical intervention versus a conservative approach. The current investigation is a retrospective review of prospectively gathered data in a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of a large cohort of PFD and MAS patients with craniofacial FD aimed to further clarify the natural history, progression, clinical symptoms, and the effect of endocrinopathy with specific regards to their sinonasal disease.

Patients and Methods

From 1998 to 2010, patients diagnosed with PFD and MAS were enrolled in an IRB-approved, natural history study of PFD/MAS at the National Institutes of Health. All subjects or their parent/guardian gave informed consent to participate. Diagnoses were confirmed by a combination of clinical features and/or molecular confirmation of a GNAS mutation. Patients underwent inpatient baseline evaluation that included a medical history and physical exam, extensive endocrine evaluation (thyroid function testing, prolactin, growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor-1, oral glucose tolerance test, overnight GH testing, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, testosterone, estrogen, parathyroid hormone, comprehensive metabolic panel, and others as indicated), 99technetium-methylene-diphosphonate bone scanning and craniofacial computed tomography (CT). The majority of patients further underwent complete otolaryngologic exam. Additional consultative services were employed as indicated and included but were not limited to ophthalmology, dental, and cardiology evaluation. Yearly follow-up was attempted for all patients.

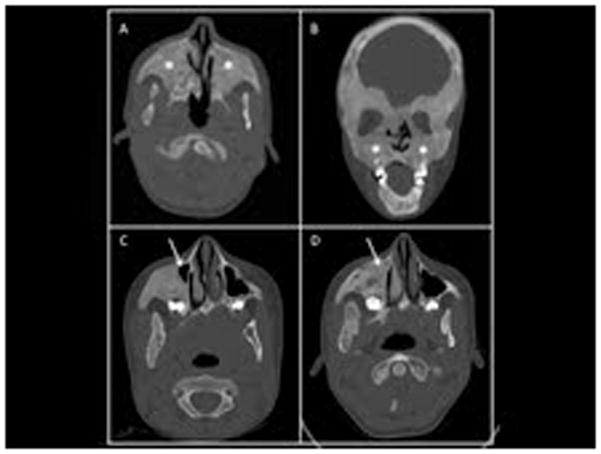

The medical record was reviewed with the following information collected: demographics, results of endocrine evaluation, clinical symptoms with regard to sinonasal disease, prior sinonasal operations, and treatment with bisphosphonates. Radiologic analysis of craniofacial CT scans was performed using axial and reconstructed coronal planes in a bone window algorithm (Figure 1). All CT scans visualized the entire sinonasal tract. In the majority of the studies the slices were 2.5 mm thick; in all studies the slices were ≤ 5mm thick.

Figure 1.

Representative computed tomography (CT) images of maxillary sinus fibrous dysplasia (FD). An example of obliteration of the maxillary sinuses by FD (asterisk) are demonstrated in these axillary (A) and coronal (B) CT images of a 13-year-old boy with sinus FD. Progression of maxillary FD in a girl with FD is demonstrated in panels C & D. At the age of 5 (C) only a small part of the right maxillary sinus is patent (arrow). By the age of 13 (D), the area is now filled in with FD (arrow).

The Lund-Mackay score, which is a tool widely used in CT imaging assessment of chronic rhinosinusitis, was modified to stage sinus involvement with FD. The modified score (defined in Table I) was used as an objective measure of the bony disease in contrast to its classically described use for characterizing mucosal disease. Bony septal involvement refers primarily to the vomer as the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid was often indistinguishable from ethmoid involvement if FD was significant. The summed score was termed the fibrous dysplasia (FD) score. Patients were included for analysis if any degree of craniofacial bony involvement was identified on CT, as well as if imaging incorporated the entire sinonasal tract. Patients were excluded from analysis if there was evidence of surgery to the sinonasal tract prior to imaging, as this could have the potential to make staging of their bony disease inaccurate.

TABLE I.

Sinonasal fibrous dysplasia staging system.

| Fibrous Dysplasia (FD) Score | |

|---|---|

| Sinuses+ (Frontal, Maxillary, Ethmoid, Sphenoid): | |

| No involvement: | 0 |

| < 50% obliteration/involvement: | 1 |

| >50% obliteration/involvement: | 2 |

| 100% obliteration/involvement: | 3 |

| Inferior+ & Middle Turbinates+, Nasal Floor+, Septum: | |

| No involvement: | 0 |

| Partial involvement: | 1 |

| Total involvement: | 2 |

| Total FD Score possible: | 38 |

Bilateral structures each scored independently.

To assess for disease progression, patients had to have been followed for greater than four years and had to have had a baseline head CT and a follow-up scan at least four years later. The CT scans were individually graded in the same manner as previously described and the difference between the first and last FD scores were recorded. Statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft® Excel (Student’s t-test) and Graph Pad Prism (regression analysis) and were considered significant with a p-value of <0.05.

Results

Demographics

A total of 130 patients were entered into the PFD/MAS NIH protocol and 112 (86%) were found to have fibrous dysplasia of the craniofacial skeleton. Six patients (5%) had a history of prior sinonasal surgery or evidence of this on their CT scans at presentation and were excluded from further baseline and longitudinal analysis. There was a slight female-to-male predominance with a ratio of 1.3 to 1. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table II. Endocrine dysfunction was identified in 84 of 112 patients (75%); a single endocrine system was involved in 48 (43%), and two or more in 36 (32%).

TABLE II.

Demographics – Cross-sectional Analysis

| Characteristic | N: |

|---|---|

| Total patients: | 106 |

| Gender (male: female): | 1 : 1.3 |

| Mean age (years) at Diagnosis (range): | 6.7 (0.2 – 79) |

| Mean age (years) at CT (range): | 24.1 (3.3 – 84.2) |

| Median age (years) at CT: | 18.4 |

| Café-au-lait spots: | 72 |

| Precocious Puberty: | 55 |

| Hyperthyroidism: | 32 |

| Growth Hormone Excess: | 27 |

| Renal Phosphate Wasting: | 38 |

| Cushing’s Syndrome: | 4 |

| Hyperparathyroidism: | 3 |

| Hyperprolactinemia: | 2 |

| Bisphosphonate use (current or prior): | 38* |

data available for n =98.

Cross-sectional analysis

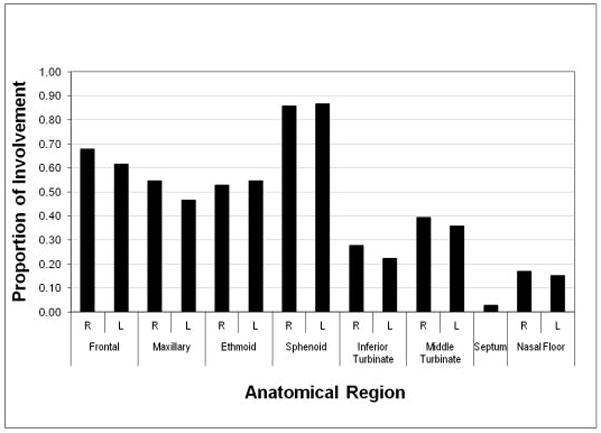

The distribution of involved sinonasal sites is displayed in Figure 2, with the most commonly involved site being the sphenoid sinus. The mean FD score for the total cohort was 13.9 (range 1 – 38). The mean FD scores for both male and female were the same as the total cohort with no statistical significance between to two (p = 0.5). The effect of endocrinopathy on the severity of bony disease was evaluated and is presented in Table III. Individuals affected with growth hormone excess or hyperthyroidism were found to have significantly higher FD scores (p= 0.01 and 0.004, respectively) compared to those unaffected, while those who had precocious puberty demonstrated no difference (p=0.11).

Figure 2.

Degree of sinonasal involvement by anatomical distribution. The proportion of the right (R) and left (L) sinus involvement for the cohort of subjects by anatomical region is shown.

TABLE III.

The effect of endocrinopathy on sinonasal fibrous dysplasia score.

| FD score – affected (mean): | FD score – unaffected (mean): | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Hormone Excess (n=27): | 17.85 | 12.28 | .01 |

| Hyperthyroidism (n=32): | 17.78 | 11.43 | .004 |

| Precocious Puberty (n=55): | 14.80 | 12.50 | .11 |

The severity of the FD score was evaluated in relation to clinical symptoms and is presented in Table IV. The incidence of headache or facial pain was reported in 33% (31/93) of individuals, chronic nasal congestion in 29% (23/79), recurrent or chronic sinusitis in 7% (5/74), and hyposmia in 7% (8/112). Only chronic congestion and hyposmia were found to have a significant association (p < 0.05 for both) with a higher FD score. Only 1 patient that reported a history of recurrent or chronic sinusitis demonstrated any evidence of sinusitis on CT and this was distant from any site of involvement of sinonasal FD. No significant difference was found between the FD scores for those that reported a history of recurrent or chronic sinusitis versus those that did not (mean 8.6 and 13.97, respectively, p=0.12).

TABLE IV.

Sinonasal fibrous dysplasia score severity and clinical symptoms.

| Clinical Symptom (affected/total) | FD score - affected (mean) | FD score – un-affected (mean) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache or Facial Pain (31/93) | 13.87 | 13.31 | .39 |

| Chronic Congestion (23/79) | 16.34 | 12.13 | <.05 |

| Recurrent or Chronic Sinusitis (5/74) | 8.60 | 13.97 | .12 |

| Hyposmia (8/112) | 22.60 | 13.30 | <.05 |

Progression analysis

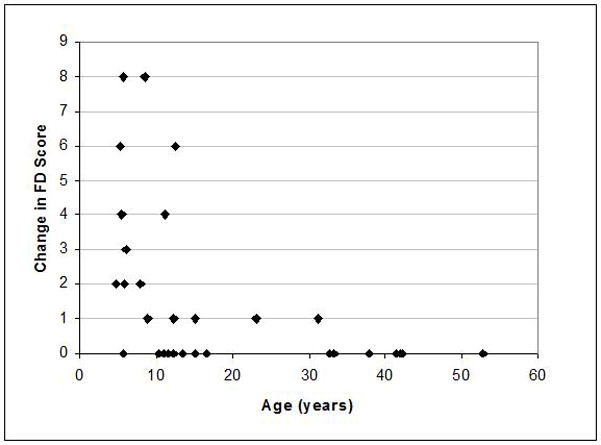

A total of 31(28%) patients met the criteria for progression analysis. The length of follow-up was 6.3 ± 1.4 years, (range 4.4 – 9.0 years). The mean age of the group at first analysis was 19 years old (range 5–53) which was not statistically different from the entire cohort at 24.1 years old (range 3.3– 84.2). Nor was the progression analysis group different from the overall cohort in terms of endocrine dysfunction and/or baseline FD score. Progression was analyzed as a function of age, and demonstrated that progression was much more common in younger patients (Figure 3). The mean age of subjects whose FD score increased was significantly less than those in whom there was no progression ((11.1 years old (range 4.8–31.2) versus 25.2 years old (range 5.6–52.8), p = 0.001, Table V)). Within the progression analysis subgroup, there was no difference in length of follow-up according to age (regression analysis of length of follow-up versus age, slope = 0.007, R2 = 0.005), confirming that the change in FD score was not biased by an age-related length of follow-up, i.e. patients who were younger at presentation were not followed longer than patients who were older at presentation. The effect of endocrinopathy and use of bisphosphonates on disease progression were evaluated and found to have no significant effect (all p-values > 0.4) (Table VI).

Figure 3.

Sinonasal FD progression. To determine the ages at which an increase in the involvement sinonasal FD occurred (disease progression), the change in the FD score (modified Lund-Mackay score, see Methods) and the age at which it occurred was determined in 31 subjects. The mean length of follow-up was 6.3 ± 1.4 years, range 4.4 –9.0 years. Each point on the graph represents a subject, the age at first evaluation, and the change in FD score at the end of follow-up. The mean age of subjects whose FD score increased was significantly less than those in whom there was no progression ((11.1 (range 4.8–31.2) versus 25.2 (range 5.6–52.8), p = 0.001), indicating that sinonasal progression mostly only occurs in childhood and that there is little progression after the age of 13.

TABLE V.

Sinonasal fibrous dysplasia progression

| (+) Progression of Disease | (−) Progression of Disease | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients: | 14 | 17 |

| Mean Age (range): | 11.1 (4.8 – 31.2) | 25.2 (5.6 – 52.8) |

| Median Age: | 8.5 | 16.6 |

| FD score change: | +2.92 | 0 |

TABLE VI.

The effect of endocrinopathy or bisphosphonate usage on progression.

| FD score change – affected (mean): | FD score change – unaffected (mean): | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth Hormone Excess (n=7/31): | 1.57 | 1.63 | .48 |

| Hyperthyroidism (n=12/31): | 1.64 | 1.68 | .41 |

| Bisphosphonate Usage (n=17/31): | 1.65 | 1.57 | .47 |

Discussion

Due to the relative rarity of PFD and MAS, sinonasal disease has not been well characterized. As a result, the literature is dominated by case reports or small case series with a focus on symptomatic effects or complications of the disease. Several authors have reported on the relatively benign findings of nasal obstruction or cosmetic defects 10–16 and others have reported on more serious complications. Ferguson 17 and Furin et al.18 reported on cases of fibrous dysplasia causing sinusitis secondary to obstruction of sinus ostia and/or mucopyocele formation, both requiring surgical intervention. Ikeda et al. 19, Berlucchi et al. 20, and Simovic et al. 14 each report on a case of visual impairment (visual loss or diplopia) secondary to optic nerve or orbital compression extending from paranasal sinus bony disease. The inherent referral bias present in such case reports and small series are not able to provide the spectrum of disease and perspective necessary to define the natural history and incidence of symptoms and complications.

Contrary to prior reports 17, involvement of the sinuses and/or nasal cavity is not rare and was found in 92% of patients in this study. This high prevalence may reflect the fact that the NIH cohort is probably a group with more severe disease, but it is also likely that many cases of FD of the sinuses and nasal cavity go undetected in patients with PFD because screening necessary to detect it (head CT or/and whole body bone scan) is often not performed. The most common problems reported in association with PFD in this cohort were headache or facial pain (33%) and chronic nasal congestion (29%). Sinusitis and hyposmia were infrequently noted in this cohort (7% each). Interestingly, only chronic nasal congestion and hyposmia were found to be significantly related to the severity of FD disease based upon the staging of the CT scans via the modified Lund-MacKay score.

Only 6 of 112 subjects had undergone prior sinonasal surgery (at an outside institution) for chronic congestion, chronic/recurrent sinusitis, transsphenoidal hypophysectomy or orbital decompression and only 7% of the study population had reported being diagnosed with chronic/recurrent sinusitis. Of those that reported chronic or recurrent symptoms, only one demonstrated any mucosal disease on CT. This finding is not unexpected since FD does not commonly obstruct the paranasal sinus ostium but rather obliterates the air-filled spaces. None of the patients have had any serious complications of sinus disease (intracranial extension, orbital extension, etc.).

The only endocrine dysfunctions found to be associated with sinonasal FD severity were with GH excess and hyperthyroidism. Other reports have noted a correlation between GH excess and craniofacial FD disease severity. Cutler et al. found that subjects with GH had a higher degree of optic neuropathy, and others have found GH excess to be associated with a greater degree of hearing deficits in FD patients21. In contrast, hyperthyroidism has not been previously associated with more significant craniofacial disease.

GH and thyroid hormone play integral roles in bone metabolism and it is not surprising that elevations from their normal levels can affect diseases of bony growth. GH has an anabolic effect on a large number of tissues including bone and cartilage. In bone, GH stimulates osteoblastic proliferation and osteoprogenitor differentiation 22. Thyroid hormone plays a key role in endochondral and intramembranous bone development, with thyrotoxicosis leading to advanced bone age, and accelerated growth23. Elevated thyroid hormone levels are associated with bone resorption and formation, uncoupled higher levels of remodeling, and a decrease in mineralization23. FD-derived osteogenic cells likely retain GH and thyroid hormone responsivity.

This study demonstrates that FD disease progression in the sinonasal region is rare after adolescence. In the subgroup in which disease progression was assessed, only three subjects demonstrated any progression after age 13, and that progression was clinically insignificant. As has been shown in regard to FD in general4,24,25, bisphosphonate treatment appeared to have no effect on the natural history of sinonasal FD.

The literature is unclear on the role of surgical treatment of sinonasal FD. Some advocate for radical resection in an effort for cure10, while others counter this argument citing significant morbidity and deformity19. Recurrence rates have been reported as high as 25% after surgical resection 26. A conservative approach appears to be the more commonly practiced treatment paradigm16,19,27,28 with surgery reserved for significant symptoms or compression of vital structures. While it is uncommon, FD lesions have the potential for malignant transformation, which may be precipitated by radiation therapy29,30. Any rapid change in the size of a lesion requires biopsy to rule out this possibility, or another bone disease such as aneurysmal bone cyst, Paget’s disease and non-ossifying fibroma.

Surgical treatment of diseased bone should be withheld except for when associated with significant symptoms and then a minimalist approach is probably most prudent. Radical resection is advised against, as we have demonstrated the incidence of complications from normal disease progression is exceedingly rare. The extent of resection should be based on the location of the pathological bone and its proximity to important sinus structures, as radical or complete resection may not be necessary or possible. Conservative surgical therapy for sinonasal disease can be accomplished with functional endoscopic sinus surgery combined with a traditional external approach if necessary to alleviate significant chronic congestion, recurrent or chronic sinusitis, and mucocele formation. Stereotactic navigation is recommended for selective cases as the disease process often distorts normal intranasal landmarks used in sinus surgery. If a surgery is indicated, it is important to control GH and thyroid hormone excess in an effort to prevent regrowth requiring additional surgery.

One limitation of this study is the referral bias of the cohort studied at our clinical research center. This is a group that tends to have more severe disease. Even in this group with significant disease the sinonasal-related morbidity was relatively mild. Another potential limitation is the use of the modified Lund-Mackay grading scale. While it appears to be useful in this context of evaluating severity of FD involvement, it will need to be validated in further studies. An additional limitation is grading of involvement of the frontal sinus in a population that included children. While usually clear, at times it could be difficult to determine whether the sinus had been obliterated by disease or had not yet developed (either due to the patient’s age or because of the disease process). To control for this potential confounder, the data were analyzed both with and without evaluation of the frontal sinus. The significance (or non-significance) of the findings was not different by either analysis (data not shown). Six subjects with a prior paranasal sinus surgery were excluded since their surgical records from outside institutions were unavailable or their surgeries were done for non-related sinusitis such as an optic nerve decompression and transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Therefore, the true incidence of chronic/recurrent sinusitis might be underestimated. However, a CT scan finding suggestive of sinusitis was documented in only one patient with symptomatic disease. The low incidence sinusitis is probably reflective of FD often obliterating the potential sinus cavity that is necessary for the development of sinusitis. Finally, bisphosphonate therapy may be a potential confounder. However, given that these drugs have not been shown to affect the course of the natural history of FD lesions in the appendicular skeleton 24,25 it may be safe to assume that this is the case in the sinonasal region.

Conclusions

Sinonasal involvement of fibrous dysplasia in MAS or PFD patients with craniofacial involvement is common, with the sphenoid sinus being the most frequently affected. Headache or facial pain, recurrent or chronic sinusitis, chronic congestion and hyposmia are common complaints in these patients, but only the latter two are clearly associated with the severity of their disease. In the case of MAS, GH and thyroid hormone excess were found to be associated with a greater degree of sinonasal bony involvement, but not associated with post pubertal progression. This suggests sinonasal disease establishment but not progression may be, at least in part, hormonally dependent. Disease progression is rare after puberty and when it occurs, it tends to be minor. Surgical intervention for sinonasal disease is infrequently indicated, but if it is required, a conservative approach is recommended.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Carter van Waes for his critical review of the manuscript

Financial Support:

Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, and Office of Clinical Director, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: none Conflict of Interest: none

References

- 1.McCune DJ. Osteitis fibrosa cystica; the case of a nine year old girl who also exhibits precocious puberty, multiple pigmentation of the skin and hyperthyroidism. Am J Dis Child. 1936;52:743–744. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albright F, Butler AM, Hampton AO, Smith PH. Syndrome characterized by osteitis fibrosa disseminata, areas of pigmentation and endocrine dysfunction, with precocious puberty in females, report of five cases. N Engl J Med. 1937;216:727–746. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins MT. Spectrum and natural history of fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21 (Suppl 2):P99–P104. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.06s219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumitrescu CE, Collins MT. McCune-Albright syndrome. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2008;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein LS, Shenker A, Gejman PV, Merino MJ, Friedman E, Spiegel AM. Activating mutations of the stimulatory G protein in the McCune-Albright syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1688–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112123252403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianco P, Riminucci M, Majolagbe A, et al. Mutations of the GNAS1 gene, stromal cell dysfunction, and osteomalacic changes in non-McCune-Albright fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:120–128. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianco P, Robey P. Diseases of bone and the stromal cell lineage. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:336–341. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riminucci M, Saggio I, Robey PG, Bianco P. Fibrous dysplasia as a stem cell disease. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21 (Suppl 2):P125–131. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.06s224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robey PG, Kuznetsov S, Riminucci M, Bianco P. The role of stem cells in fibrous dysplasia of bone and the Mccune-Albright syndrome. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2007;4 (Suppl 4):386–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valentini V, Cassoni A, Marianetti TM, Terenzi V, Fadda MT, Iannetti G. Craniomaxillofacial fibrous dysplasia: conservative treatment or radical surgery? A retrospective study on 68 patients. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009;123:653–660. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318196bbbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman AM, Ray PE, Bristow MR. Expression of α-subunits of G proteins in failing human heart: A reappraisal utilizing quantitative polymerase chain reaction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1991;23:1355–1358. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90182-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camilleri AE. Craniofacial fibrous dysplasia. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1991;105:662–666. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100116974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolger WE, Ross AT. McCune-Albright syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2002;65:69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(02)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simovic S, Klapan I, Bumber Z, Bura M. Fibrous dysplasia in paranasal cavities. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 1996;58:55–58. doi: 10.1159/000276797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stompro BE, Bunkis J. Surgical treatment of nasal obstruction secondary to craniofacial fibrous dysplasia. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1990;85:107–111. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199001000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman MD, Rao VM, Lowry LD, Kelly M. Fibrous dysplasia of the paranasal sinuses. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1986;95:222–225. doi: 10.1177/019459988609500217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson BJ. Fibrous dysplasia of the paranasal sinuses. American journal of otolaryngology. 1994;15:227–230. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furin MM, Eisele DW, Carson BS. McCune-Albright syndrome (polyostotic fibrous dysplasia) with intracranial frontoethmoid mucocele. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;116:559–562. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda K, Suzuki H, Oshima T, Shimomura A, Nakabayashi S, Takasaka T. Endonasal endoscopic management in fibrous dysplasia of the paranasal sinuses. American journal of otolaryngology. 1997;18:415–418. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(97)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berlucchi M, Salsi D, Farina D, Nicolai P. Endoscopic surgery for fibrous dysplasia of the sinonasal tract in pediatric patients. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2005;69:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutler CM, Lee JS, Butman JA, et al. Long-term outcome of optic nerve encasement and optic nerve decompression in patients with fibrous dysplasia: risk factors for blindness and safety of observation. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:1011–1017. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000254440.02736.E3. discussion 1017–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohlsson C, Vidal O. Effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factors on human osteoblasts. European journal of clinical investigation. 1998;28:184–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassett JH, Williams GR. The molecular actions of thyroid hormone in bone. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2003;14:356–364. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plotkin H, Rauch F, Zeitlin L, Munns C, Travers R, Glorieux FH. Effect of pamidronate treatment in children with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4569–4575. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiMeglio LA. Bisphosphonate therapy for fibrous dysplasia. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2007;4 (Suppl 4):440–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edgerton MT, Persing JA, Jane JA. The surgical treatment of fibrous dysplasia: with emphasis on recent contributions from cranio-maxillo-facial surgery. Ann Surg. 1985;202:459–479. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198510000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uzun C, Adali MK, Koten M, Karasalihoglu AR. McCune-Albright syndrome with fibrous dysplasia of the paranasal sinuses. Rhinology. 1999;37:122–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JS, FitzGibbon E, Butman JA, et al. Normal vision despite narrowing of the optic canal in fibrous dysplasia. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1670–1676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruggieri P, Sim FH, Bond JR, Unni KK. Malignancies in fibrous dysplasia. Cancer. 1994;73:1411–1424. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940301)73:5<1411::aid-cncr2820730516>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggieri P, Sim FH, Bond JR, Unni KK. Osteosarcoma in a patient with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia and Albright’s syndrome. Orthopedics. 1995;18:71–75. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19950101-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]