Abstract

Targeting nanoparticles (NPs) loaded with drugs and probes to precise locations in the body may improve the treatment and detection of many diseases. Generally, to achieve targeting, affinity ligands are introduced on the surface of NPs that can bind to molecules present on the cell of interest. Optimization of ligand density is a critical parameter in controlling NP binding to target cells and a higher ligand density is not always the most effective. In this study, we investigated how NP avidity affects targeting to the pulmonary vasculature, using NPs targeted to ICAM-1. This cell adhesion molecule is expressed by quiescent endothelium at modest levels and is upregulated in a variety of pathological settings. NP avidity was controlled by ligand density, with the expected result that higher avidity NPs demonstrated greater pulmonary uptake than lower avidity NPs in both naïve and pathological mice. However, in comparison with high avidity NPs, low avidity NPs exhibited several-fold higher selectivity of targeting to pathological endothelium. This finding was translated into a PET imaging platform that was more effective in detecting pulmonary vascular inflammation using low avidity NPs. Furthermore, computational modeling revealed that elevated expression of ICAM-1 on the endothelium is critical for multivalent anchoring of NPs with low avidity, while high avidity NPs anchor effectively to both quiescent and activated endothelium. These results provide a paradigm that can be used to optimize NP targeting by manipulating ligand density, and may find biomedical utility for increasing detection of pathological vasculature.

Keywords: Nanoparticle, Targeted Drug Delivery, Endothelial Targeting, ICAM-1, Molecular Imaging, Multivalent Interactions

Targeting nanoparticles (NPs) to desired destinations in the body holds the promise of advancing diagnostic and therapeutic interventions to a new level of precision and efficacy.1–9 In most cases, this goal is achieved by coupling a nanoparticle’s surface with affinity ligands that bind to molecules expressed on target cells (e.g., antibodies). NPs with size ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers can carry multiple copies of affinity ligands, enabling multivalent interactions of NPs with their target determinants, which generally enhances NP avidity and therefore favors preferential delivery to sites of interest.10–15

One of the key aspects of affinity targeting is to define the optimal ligand density on the surface of the NP, a parameter that may vary depending on the NP design and application. However, the highest density may not necessarily be the most desirable. For example, excessive ligand coating beyond the density that saturates NP binding will not further improve targeting, but may result in increased adverse effects and economic implications.16 In the case of stealth PEG-carriers, the ligand density should be kept at a minimal level sufficient to avoid NP unmasking and elimination by the reticuloendothelial system.17, 18 In some instances, lowering density of ligand molecules enhances their congruency to the surface presentation of the target molecules, providing more effective binding and uptake by target cells.19, 20 Furthermore, an excessive avidity to cellular receptors may impair NP dissociation in endosomes and subsequent cellular transport of cargoes.21

One of the key determinants of optimal ligand density is tissue selectivity of NP targeting. In many cases, especially in detection and imaging of pathology, the biomedical utility of a given drug delivery system is less dependent on the absolute amount of cargo delivered, than on the “target/non-targetratio”.22, 23 Very often, so called “specific” markers expressed on target cells are also expressed at lower levels in other areas of the body.24–29 Due to this, the relative expression, organization, and accessibility of the anchoring molecules on target cells, as compared to the rest of the body, are critical considerations in determining optimal ligand coating. Increasing NP avidity above a certain optimum may enhance “off-target” uptake by tissues expressing basal low levels of the target antigen. When translated from the laboratory to clinical application, this change in tissue selectivity can be the difference between an effective targeting agent, rather than one with side effects or inadequate signal-to-noise ratio.

In the present study, we explored the effect of varying surface density of an antibody to Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on targeting NPs to normal and inflamed pulmonary vasculature in mice. ICAM-1 is constitutively expressed at a basal level on endothelial cells in quiescent vasculature and its expression is markedly elevated in pathologically activated endothelium. Therefore, ICAM-1 represents an attractive target for detection of and intervention in pathologically altered vasculature, for example, in acute lung injury (ALI) and other conditions involving vascular inflammation.11, 30, 31 We found that controlled reduction of anti-ICAM-1 on a NP surface enhances selectivity of targeting to inflamed compared to normal vasculature, which improves positron emission tomography (PET) detection of pulmonary inflammation. To elucidate the mechanism of this phenomenon, we performed simulations of anti-ICAM-1/NPs binding to target cells, which revealed the key role of multivalent anchoring of low-avidity NPs to the inflamed versus quiescent endothelium.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of the animal model: enhancement of ICAM-1 expression in the pulmonary vasculature of mice challenged with endotoxin

ICAM-1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that supports firm adhesion of activated leukocytes to the endothelium at sites of inflammation.32, 33 It is expressed constitutively in quiescent vasculature at the level of approximately 1–2 × 105 binding sites per endothelial cell and its expression is elevated 3–5 fold in pathological vasculature, as a result of NFκB-mediated inflammatory activation of endothelium by cytokines, oxidants and abnormal flow.34–36

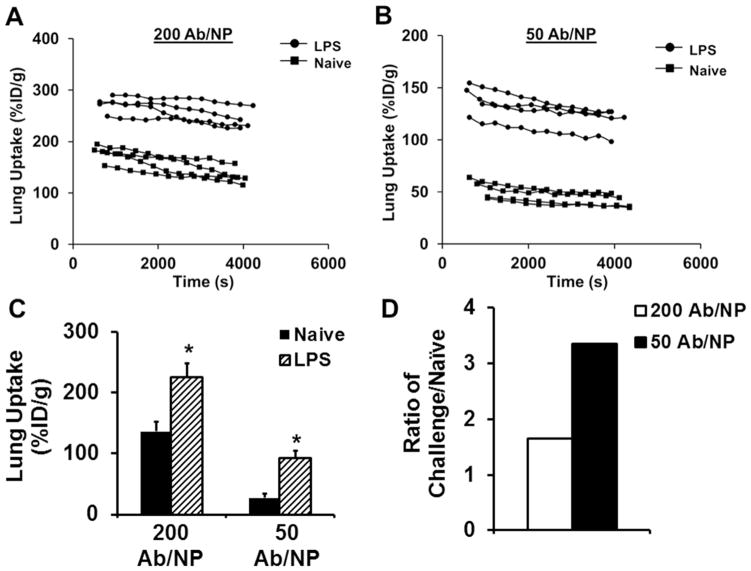

In order to study targeting of anti-ICAM-1/NPs to inflamed endothelium in vivo, we employed a mouse model of Acute Lung Injury (ALI) using intratracheal installation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 8mg/kg). This challenge caused approximately four-fold elevation of ICAM-1 mRNA in lung tissue within several hours and this up-regulation of at least two-fold continued through 24 hours. Protein levels correlated with these data and exhibited over a two-fold increase in ICAM-1 expression after 24 hours (Fig. 1A and 1B). These data are in good accordance with the literature.34, 35, 37, 38 Furthermore, pulmonary uptake of radiolabeled ICAM-1 antibody injected intravenously in mice 24 hours after LPS challenge was ~2.5 times higher than in control mice (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the pulmonary uptake of radiolabeled non-specific IgG was at the low basal level (<10–15 %ID/g) in both naïve and LPS-challenged mice (not shown). This control affirmed the specificity of targeting ICAM-1 antibody, mediated by binding to the antigen in the vascular lumen, but not tissue edema or binding to leukocytes and other Fc-receptor bearing cells in the tissue. In contrast with PCR and western blotting which characterize the total content of ICAM-1 in the lung tissue, including airway cells that also respond to the insult by elevated expression, specific uptake of radiolabeled ICAM-1 antibody injected in the circulation characterizes ICAM-1 on the luminal surface of the blood vessels. This sub-population of ICAM-1 molecules is of great interest, since it is involved in leukocyte trafficking and accessible to targeted interventions administered intravenously.

Figure 1.

Model of acute lung injury in mice. (A) Messenger RNA levels of ICAM-1 in LPS-treated mice at a dose of 8 mg/kg. (B) Western blot analysis and quantification of up-regulation of ICAM-1 in this model of inflammation. (C) Anti-ICAM-1Ab localization in the blood and lung in naïve and LPS-challenged mice. Data represented as mean ± S.D.;*, p < 0.05.

Reduction of ICAM-1 ligand density on NP surface enhances selectivity of detection for inflamed pulmonary vasculature

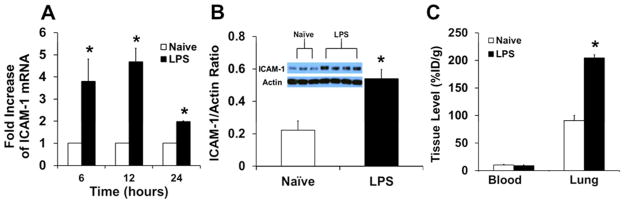

Next, we examined pulmonary uptake of anti-ICAM-1/NPs after intravenous injection in mice (~200 nm diameter spheres carrying 0–200 antibody molecules per particle, Supporting Figure 1 & Supporting Table 1). In naive animals, pulmonary uptake of anti-ICAM-1/NPs was markedly higher than control IgG-coated NPs (IgG/NPs) and was a function of anti-ICAM-1 surface density (Fig. 2A). Reduction of a surface coverage below ~120 anti-ICAM-1 molecules per NP (i.e., below ~60% NP surface coverage) led to a decrease in pulmonary uptake of anti-ICAM-1/NPs. Decreasing surface coverage below 50 anti-ICAM-1 molecules per NP (below ~25% surface coverage) practically ablated ICAM-1-specific targeting, i.e., pulmonary uptake of anti-ICAM-1/NPs was no different from that of IgG/NPs.

Figure 2.

Utilization of Ab density to control lung localization. (A) In vivo lung accumulation as a function of anti-ICAM-1 surface density. Data points highlighted in red correspond to ICAM-1 surface densities used to examine tissue selectivity (dashed line denotes control IgG NPs). (B) Using anti-ICAM-1 surface density to increase tissue selectivity in a model of acute lung injury (dashed line denotes control IgG in LPS treated mice). (C) Tissue selectivity of different ICAM-1 formulations. Data represented as mean ± S.D. (n = 4), p < 0.05.

Another critical factor to take into account is how antigen expression can influence the interactions with NPs. There have been reports that have looked at the effect of antigen density of targeted NPs in vitro but this aspect has yet to be examined in vivo. 20, 37, 39, 40 Here we addressed this aspect of anti-ICAM-1/NP targeting using the LPS-induced model of ALI characterized in the previous section. As expected, LPS-challenge led to a marked elevation in the pulmonary uptake of anti-ICAM-1/NPs, to the level of ~300 and 90 %ID/g for high (200 Ab/NP) and low (50 Ab/NP) avidity NP formulations, respectively (Fig 2B). Thus, absolute value of pulmonary uptake of the low avidity NPs was three-fold lower than that of high avidity NPs. However, in relative terms, LPS-challenge led to ~2.5-fold versus ~5-fold increase in the pulmonary uptake of high versus low avidity NPs (Fig. 2C & Table 1). Since the difference between normal and pathological tissue is the most important parameter for the detection of pathology, a 2-fold increase in selectivity between quiescent and inflamed endothelium by reduction of NP avidity may provide an advantage for this application, for example, for investigative and diagnostic imaging.

Table 1.

a Lung Tissue Selectivity Summary

| Formulation | Lung Uptake (% ID/g)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | Challenged | C/N | |

| ICAM-1Ab | 81 | 193 | 2.4 |

| 200Ab/NP | 116 | 280 | 2.4 |

| 50 Ab/NP | 14 | 74 | 5.3 |

Mice were injected via jugular vein with different ICAM-1 formulations, and organs harvested 30 min post-injection. Naïve and Challenged are lung uptake values represented as % of injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g). C/N denotes the ratio of Challenged versus Naïve lung uptake. IgG levels were subtracted off raw values to account for non-specificity.

Enhanced detection of pulmonary vascular inflammation using PET imaging of low avidity nanoparticles

Selective targeting of low avidity anti-ICAM-1/NPs to pathological endothelium may provide non-invasive, real-time detection and visualization of inflamed vasculature. In particular, PET imaging has the potential to yield a clinically applicable diagnostic platform that could serve this purpose. We have tested this approach in mice using anti-ICAM-1/NPs labeled with the 124 I PET isotope (t1/2 ~4.2 days) covalently bound to the polymer backbone. As we reported in a recent paper describing these radiolabeled probes, this labeling methodology eliminates artifacts of isotope detachment from nanoparticles.10

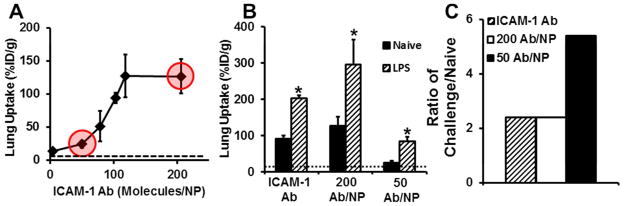

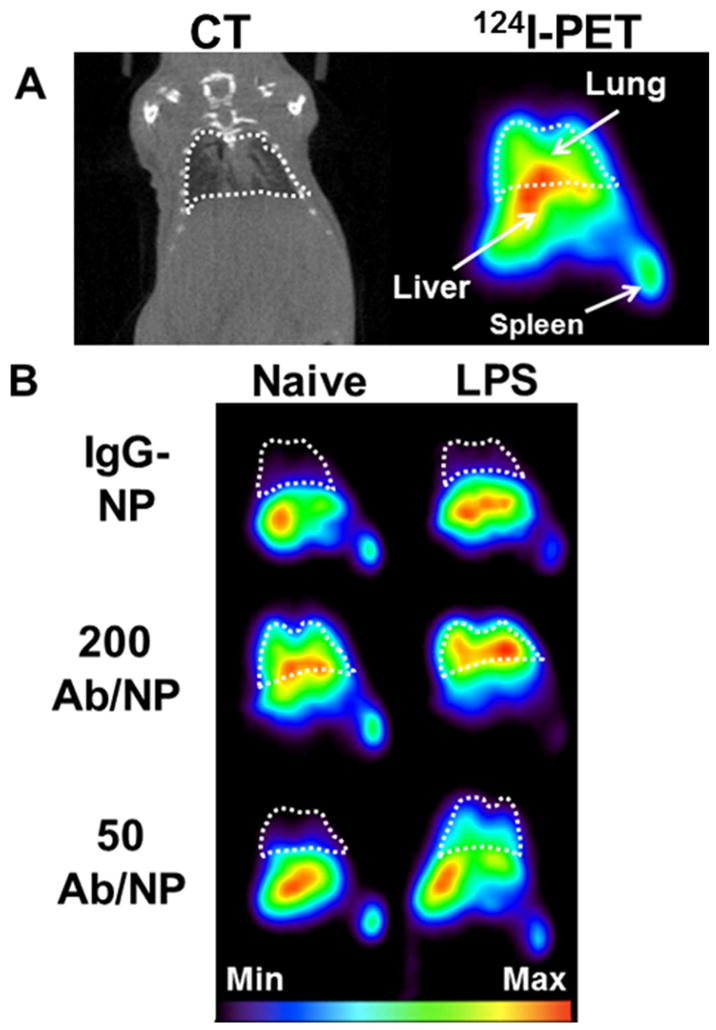

Similar to the biodistribution study in Fig. 2, mice were challenged with LPS 24 hours prior to IV injection of either high or low avidity anti-ICAM-1/NPs, or control IgG/NPs and imaged using dynamic micro-PET and computed tomography (CT) over a period of 1 hour. Figure 3 and Supporting Figures S2–S4 display PET/CT imaging results, revealing the signal of anti-ICAM-1/NPs in the thorax and major splanchnic organs, predominantly the liver. For quantitative analysis of pulmonary PET radiotracer signal, CT images were used to anatomically define the lung region-of-interest (ROI) in the thorax. ROI analysis in real-time affirmed that low avidity anti-ICAM-1/NPs consistently displayed more profound elevation of pulmonary signal in LPS-challenged versus naïve mice relative to the difference displayed by high avidity NPs (Figure 4A & B). Figure 4C represents lung targeting averaged over the scan for each animal and this exhibited similar trends to the 125 I radiotracing data and correlated with image observations. Furthermore, when determining the ratio of lung targeting of challenged over naïve mice for both NP formulations, pulmonary uptake increased 1.7-fold for the high avidity formulation and 3.4-fold in the low avidity formulation (Figure 4D). Therefore, lowering of anti-ICAM-1/NP avidity by controlled reduction of antibody surface density does provide a tangible benefit of a two-fold enhancement of the selectivity of imaging pathological endothelium.

Figure 3.

(A) Coronal sections of real-time in vivo CT(left) and PET(right) images acquired after administration of ICAM-1-targeted (200 Ab/NP) [124I]-NP in a naïve mouse to demonstrate organs of interest and anatomical orientation (white dashed-line corresponds to lung space defined from CT images). (B) Different formulations of IgG controls and anti-ICAM-1 (Ab coverage: 50 and 200 Ab/NP) in naïve and LPS-treated mice were examined for lung localization over a period of 1 hour by 124I-PET. Each image represents a summed image of all frames captured within the 1 hour time frame.

Figure 4.

(A & B) Lung uptake (%ID/g) in real-time extrapolated from regions-of-interest (ROIs) drawn on lung volumes from PET images over the 1 hour scan time for both ICAM-1 targeted formulations in naïve and LPS-challenged mice. (C) Average lung uptake of anti-ICAM-1 formulations extrapolated from regions-of-interest (ROIs) drawn on lung volumes from PET images at 1 hour p.i. with IgG levels subtracted to account for non-specificity (D) Ratio of LPS-challenged over naïve animals targeted with anti-ICAM-1 formulations extrapolated from ROIs. Data represented as mean ± S.D. (n = 4); *, p < 0.05.

Computational analysis of anti-ICAM-1/NP selectivity to inflamed endothelium

The practical utility of improved outcomes in imaging specificity warranted a more elaborate mechanistic analysis of our empirical findings. Computational analysis and modeling of NPs binding to target molecules may provide more general insight and thus assist in devising optimal delivery systems.41, 42 This dynamic process is determined by affinity, surface density, spatial organization and orientation of ligand molecules on the carrier surface, as well as surface density, accessibility and spatial organization of target determinants, among other factors including kinetics of blood clearance and perfusion pattern in the target tissue. The interplay of these factors (many of which are not fully understood for any targeting system) is extremely complex. The majority of studies in this area use data obtained in vitro in oversimplified model systems. For example, endothelial cells in culture normally express ICAM-1 at markedly lower basal levels than quiescent endothelial cells in vivo. However, in vitro studies by several groups documented that: i) binding of anti-ICAM-1/NPs to both quiescent and cytokine-activated endothelial cells is dependent on anti-ICAM-1 surface density; ii) anti-ICAM-1/NPs with avidity below a certain threshold do not bind to quiescent endothelial cells, yet still are capable of binding to cytokine-activated cells; and, iii) this trend is further accentuated by the shear stress in the range of flow typical of veins, the vascular segment where the majority of ICAM-1-mediated transmigration of activated leukocytes occurs.19, 43–45 Based on this, we used computational analysis of anti-ICAM-1/NPs binding to quiescent versus inflamed endothelium to examine the molecular interactions of these binding events.

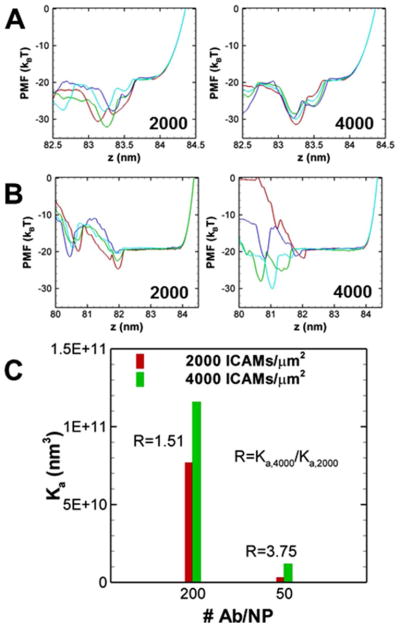

For the computational analysis, we modeled binding of anti-ICAM-1/NPs coated with 50 and 200 Ab/NP to endothelial cells expressing approximately 2000 or 4000 ICAM-1 molecules/μm2 to mimic resting or pathologically activated endothelium, respectively.46, 47 An experimentally measurable quantity which is central to quantifying the avidity is the association constant (Ka) of NP binding to a cell surface. We have shown in earlier work that using our model, 48–50 we can compute the association constant through the calculation of the potential of mean force (PMF); this procedure is outlined in the Methods section. Specifically, the negative of the PMF at a given distance between the NP and the cell surface (z) physically corresponds to the log probability of locating the NP at a given distance from the surface (z). Figure 5A and B depict the individual PMF profiles of high and low avidity NPs. The different colored traces of PMF in these figures correspond to calculations performed using four independent simulations. The calculated association constants of the NP binding to cells for the different antibody densities and for different antigen densities are depicted in Figure 5C. Figure 5C shows that increasing the antibody density from 50 to 200 per NP enhances the binding affinity Ka by an order of magnitude (at both values of the ICAM-1 surface densities investigated). As can be inferred by counting the number of minima between the unbound state and the bound state at equilibrium (the state or value of z corresponding to the lowest PMF value) and consistent with previous simulations, the enhancement in the binding affinity is due to an increase in multivalent interaction. At a given antibody density, an increase in the ICAM-1 density on cell surface also enhances the binding affinity. We define the selectivity factor as the ratio of R = Ka,4000/Ka,2000, as shown in Fig. 5, where R=1.51 and 3.75 for 200 and 50 Ab/NP, respectively. This is consistent with experimental observations, which also report that the selectivity factor is larger at the lower antibody density and is in accord with prior simulations describing selectivity.51

Figure 5.

(A) The individual PMF profiles at antibody coverage of Nab=200/NP and ICAM-1 density of 2000 ICAM-1/μm2 (left) and 4000 ICAM-1/μm2 (right). (B) The individual PMF profiles at antibody coverage of NAb=50/NP and ICAM density of 2000 ICAM-1/μm2 (left) and 4000 ICAM-1/μm2 (right). Different colors correspond to four independent realizations based on which the statistical error in the binding affinity is computed and reported as one standard deviation. (C) The binding affinities (Ka) at different antibody coverage and ICAM-1 surface coverages.

The ICAM-1 surface density impacts association constant Ka by two mechanisms (two terms in Eq. (1)): the accessible area for ICAM-1 in unbound state and the PMF W(z). Here, r0 is the outer radius of the annulus distribution and Aaccess is the accessible area or surface area per free ICAM-1 molecule (which is the reciprocal of ICAM-1 surface density). From the PMF profiles in Figure 5, it can be inferred that in both 2000 and 4000 ICAM-1/μm2 cases, there are statistically three firm ICAM-1 bonds formed at the equilibrium state. As a result, the last term in Eq. (1) due to the PMF does not vary significantly. In this case, the selectivity factor is influenced mainly by the area term and remains modest. At low antibody density, however, all four realizations of PMF for the 2000 ICAM-1/μm2 system show two bonds per NP at equilibrium; whereas, some realizations for the 4000 ICAM-1/μm2 show three bonds per NP at equilibrium. Given that the change in multivalency exponentially impacts the PMF, the selectivity factor is significantly higher in the NP with lower antibody coverage.

Conclusion

The presented results support the strategy that optimization of ligand density on NPs to fit with anchoring molecules optimizes targeting. In general, higher avidity targeting NPs typically enhance binding to the target.4, 10–12, 15, 52 Yet, in many cases there is a tradeoff between absolute level of delivery and its selectivity. Our data provide the first evidence in vivo that in some cases carriers with lower ligand density can be more advantageous in the detection of a pathological target than its higher ligand density counterpart. In particular, low avidity NPs more selectively detected vascular pulmonary inflammation due to multivalent interactions between NPs and a target expressed at an elevated density by pathological endothelium. The particular target molecule examined in this study, ICAM-1, can be used for directing carriers to normal endothelium as a prophylactic, and permits even higher uptake of NPs by abnormal endothelium.30, 53–56 Radiolabeled ICAM-1 targeted ligands and NPs have also been used for detection of inflamed endothelium for this same reason.57–59 Delivery of drugs by low avidity anti-ICAM-1/NPs may be inferior to high avidity NPs due to the dose limitation, yet imaging of inflammation would likely benefit from using NPs with marginal avidity due to enhanced selectivity at the site of interest. It will be interesting to investigate whether the paradigm for enhanced selectivity of targeting guided by multivalent anchoring is expandable to other targets.

Methods

Materials and Instrumentation

Deionized (DI) water (18 MΩ-cm resistivity) was dispensed by a Millipore water purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Control rat IgG was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). The rat anti-mouse CD54/ICAM-1 Ab (YN1 clone) was purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Poly(4-vinylphenol, PVPh) (25,000 average Mw) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

PVPh-NP Preparation and Characterization

PVPh polymer was dissolved in acetone at desired concentrations. One part PVPh/acetone solution was added (5 mL/min) to five parts DI water with vigorous stirring at the highest vortex setting (Vortex Genie 2, Scientific Industries Inc, Bohemia, NY). The mixture was continuously vortexed for 1 min following addition of polymer. Acetone was removed by evaporation under ambient conditions. NP diameter was determined via dynamic light scattering (DLS, 90 Plus Particle Sizer, Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY). All particle preparations were reproduced a minimum of three times and independent DLS measurements were made of each individual preparation.

Synthesis and Characterization of anti-ICAM-1-NPs

Spherical polymeric NPs were synthesized from a 25 kDa poly-4-vinyl phenol (PVPh) polymer as described Simone et al.10 For targeting studies, PVPh-NPs were radiolabeled (with either 124I or 125I) and then coated with antibody (Ab) directed to ICAM-1, control IgG, or the combination of the two. A saturating antibody coverage (~200 Ab/NP) was used for fully coated (100% coverage) NPs. This was based off antibody packing approximations on the surface of a NP and confirmed by tracing radiolabeled IgG adsorption onto NPs. Instances where lower anti-ICAM coverages were used, the total amount of antibody added was balanced to a saturating coverage with control IgG molecules. NP formulations ranged from 180–210 nm in hydrodynamic radius as measured by dynamic light scattering after coating.

Direct PVPh-NP radioiodination

PVPh-NPs were radiolabeled directly with either [125I]NaI (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA), or [124I]NaI (IBA Molecular, Dulles, VA). Briefly, 100 μL of PVPh-NPs (4 mg/mL, in DI water) was incubated with iodination beads (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, IL) and a radioiodine solution (40 μCi to 2 mCi of 125/124I in 10–100 μL 20 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen)). The reaction was terminated by separating radiolabeled NPs from iodination beads. Due to the high labeling efficiency, [125/124I]PVPh-NP were used for Ab-coating without further purification. [125/124I]PVPh-NP labeling efficiency and free radioiodide content was determined with a standard trichloroacetic acid (TCA) assay traditionally used for characterizing radiochemical purity of labeled protein preparations.

Ab coating of [125/124I]PVPh-NP

[125/124I]PVPh-NP coating with Abs was performed using established adsorption techniques based on interactions between the hydrophobic domains on the surface of Abs and the relatively hydrophobic PVPh-NP surface. Ab (in aqueous buffered solution containing ≤0.09 % sodium azide) was added to PVPh-NP suspension in DI water, vigorously vortexed for 1 min, and then placed on a rotating shaker for 1 h at room temperature. Ab coating efficiency was determined by measuring [125I]IgG adsorbed onto NP relative to IgG mass added. Briefly, the NP/Ab mixture was centrifuged at 12,000×g for 3 min and the supernatant (unbound [125I]IgG) was separated from the NP pellet (with [125I]IgG bound). To determine NPs coating densities, NPs were coated with IgG with a tracer amount of 125I-labeled IgG. A saturating antibody density of the PVPh surface was ~206 ± 5 molecules/NP (~8000 antibody molecules/μm2). For variable anti-ICAM-1 coating densities, total antibody density was balanced to saturation with IgG. For in vivo targeted NPs, Abs were added at a theoretical maximum concentration based upon calculations of total surface area available on the PVPh-NP for protein adsorption. Briefly, using A = 4πr2, NP surface area was approximated to ~27 μm2 (where NP diameter is 92 nm, from TEM analysis).10 Treating Ab as a block, its footprint equates to ~120 nm2. Ultimately, this corresponds to a theoretical approximation of ~225 mAbs/NP.

Biodistribution studies

All animal studies were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted by the US National Institutes of Health and approved by the University of Pennsylvania IACUC. Naïve or LPS-challenged C57BL/6 female mice (18–22 g; n = 3–5 per group) were anesthetized and injected intravenously (IV) via jugular vein with approximately 2 μCi [125I]PVPh-NPs coated with anti-ICAM-1 formulations or control IgG. LPS-challenged mice were administered LPS (B5, 8 mg/kg) intra-tracheally 24 h prior to NP injection. Formulations were sterilized by passing through a 0.2 μM filter prior to injection. Mice were injected with approximately 10 mg/kg Ab-PVPh-NP formulated with a tracer amount of Ab-[125I]PVPh-NPs in 200 μL 1 wt % BSA/PBS. At 30 min post-injection (p.i.) of NP, blood was collected from the retro-orbital sinus and organs (heart, kidneys, liver, spleen, lungs, brain, and thyroid) were collected and weighed. Tissue radioactivity was measured in a γ-counter, and targeting parameters including percent of injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g) have been determined as described.60 Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test, where p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

PET and CT Image Acquisition and Analysis

Imaging studies were performed on a Philips Mosaic Animal PET (A-PET) scanner 61 and a MicroCATII scanner (CTI-Imtek Co.). Naïve or LPS-challenged C57Bl/6 male mice (22–29 g) were anesthetized with 1–2 % vaporized isoflurane and injected via tail-vein with approximately 150–250 μCi of Ab-[124I]PVPh-NP (approximately 10 mg/kg in 200 μL 1 wt % BSA/PBS). LPS-challenged mice were administered LPS (B5, 8 mg/kg) intra-tracheally 24 h prior to NP injection. To minimize resolution artifacts associated with thoracic motions, mice were affixed with a respiratory gating device. PET Image acquisition commenced 5–10 min post-injection, with dynamic scans carried out over one hour (5 min per frame; image voxel size 0.5 mm3). MicroCT images were acquired following PET scanning. Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was performed using AMIDE (http://amide.sourceforge.net) on reconstructed images, guided by detailed mouse anatomy from microCT images of each imaged animal. ROI’s were drawn over the lungs of each mouse.

Computational Methods

In our computational method, the nanoparticle is modeled as a rigid sphere with diameter of 100 nm, the NP is decorated by a number of anti-ICAM-1Ab (NAb) which are uniformly distributed on its surface. The cell surface is treated as a rigid flat surface with a number of diffusive ICAM-1 (NICAM-1). The interactions between the NP and cell surface are through the interactions between antibodies and antigens, and the interactions are modeled as the Bell model 62:ΔGr(d) = ΔG0 + 1/2 kd2, where d is the distance between the reaction sites of the interacting antibody and antigen, k is the interaction bond force constant and ΔG0the free energy change at equilibrium state (d=0). We choose ΔG0 from the experimental measurements of Muro et al.46, the bond spring constant by fitting rupture force distribution data reported from single-molecule force spectroscopy.47, 63 We also account for the ICAM-1’s flexural movement by allowing it to bend and rotate; the flexural rigidity is set at 7000 pN · nm2 7000 pN.nm2. Metropolis Monte Carlo steps are employed for: (i) bond formation/breaking, (ii) NP translation and rotation, and (iii) and ICAM-1 translation. Move (i) is selected randomly with a probability of 50%, and in the remaining 50%, the NP translation, rotation, and ICAM-1 translation are selected randomly with probability of 0.5 NAb/Nt, and (Nt − NAb)/Nt, respectively; Nt is the combined total number of antibodies (NAb) and ICAM-1 molecules(NICAM-1). An adaptive step size for NP translation/rotation and ICAM-1 diffusion is implemented to ensure a Metropolis acceptance rate of 50%.

To compute the potential of mean force (PMF), we first choose a reaction coordinate z, which is the vertical displacement between the center of NP and cell surface, then along z we perform umbrella sampling in multiple windows with harmonic biasing potentials to facilitate the sampling. The window size of the umbrella sampling is chosen as Δz=0.05 nm and the harmonic biasing potential in each window is chosen to be 0.5 ku (z − zo.i)2 = 0.5·ku (Δz)2 = 1.0×10−20 J, where ku is the harmonic force constant and zo,i is the vertical coordinate of the center of window i. By updating the zo,i values, the NP is slowly pushed toward to the cell surface. A total of 200 million Monte Carlo steps are performed in each window and the histogram is saved. All the relevant parameters including the window size Δz, strength of the biasing potential ku and the sampling size in each window have been tested to ensure convergence. The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) algorithm64 is used to unbias and combine the histograms in different windows to form a complete PMF (W(z)) profile using a tolerance factor of 10−6. Using the potential of mean force (PMF) profiles we compute the binding affinity48–50 as:

| (1) |

where NAb is the number of antibodies on NP, Nb the number of bonds formed, Δω the rotational mobility of NP, the accessible area for the ith ICAM-1 in bound state, the accessible area for the ith ICAM-1 in unbound state, ANC,b the accessible area for the NP and W(z) the calculated PMF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eric Simone, Divya Menon and Jenny Arguiri for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant (HL-087036-01A2) to V.R.M.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Nanoparticle characterization of size, polydispersity and antibody coverage are detailed in Supporting Figure 1 and Table 1. PET/CT coronal sections of full experimental groups can be found in in Supporting Figures 2–4 This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Poon Z, Lee JA, Huang S, Prevost RJ, Hammond PT. Highly Stable, Ligand-Clustered “Patchy” Micelle Nanocarriers for Systemic Tumor Targeting. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nahrendorf M, Keliher E, Marinelli B, Leuschner F, Robbins CS, Gerszten RE, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK, Weissleder R. Detection of Macrophages in Aortic Aneurysms by Nanoparticle Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:750–757. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H, Lytton-Jean AK, Chen Y, Love KT, Park AI, Karagiannis ED, Sehgal A, Querbes W, Zurenko CS, Jayaraman M, et al. Molecularly Self-Assembled Nucleic Acid Nanoparticles for Targeted in Vivo Sirna Delivery. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shuvaev VV, Ilies MA, Simone E, Zaitsev S, Kim Y, Cai S, Mahmud A, Dziubla T, Muro S, Discher DE, et al. Endothelial Targeting of Antibody-Decorated Polymeric Filomicelles. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6991–6999. doi: 10.1021/nn2015453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan H, Myerson JW, Hu L, Marsh JN, Hou K, Scott MJ, Allen JS, Hu G, San Roman S, Lanza GM, et al. Programmable Nanoparticle Functionalization for in Vivo Targeting. FASEB J. 2013;27:255–264. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimoni O, Postma A, Yan Y, Scott AM, Heath JK, Nice EC, Zelikin AN, Caruso F. Macromolecule Functionalization of Disulfide-Bonded Polymer Hydrogel Capsules and Cancer Cell Targeting. ACS Nano. 2012;6:1463–1472. doi: 10.1021/nn204319b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perche F, Patel NR, Torchilin VP. Accumulation and Toxicity of Antibody-Targeted Doxorubicin-Loaded Peg-Pe Micelles in Ovarian Cancer Cell Spheroid Model. J Control Release. 2012;164:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hood E, Simone E, Wattamwar P, Dziubla T, Muzykantov V. Nanocarriers for Vascular Delivery of Antioxidants. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:1257–1272. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearce TR, Shroff K, Kokkoli E. Peptide Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles for Anticancer Drug Delivery. Adv Mater. 2012;24:3803–3822. 3710. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simone EA, Zern BJ, Chacko AM, Mikitsh JL, Blankemeyer ER, Muro S, Stan RV, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial Targeting of Polymeric Nanoparticles Stably Labeled with the Pet Imaging Radioisotope Iodine-124. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5406–5413. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muro S, Gajewski C, Koval M, Muzykantov VR. Icam-1 Recycling in Endothelial Cells: A Novel Pathway for Sustained Intracellular Delivery and Prolonged Effects of Drugs. Blood. 2005;105:650–658. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang W, Kim BY, Rutka JT, Chan WC. Nanoparticle-Mediated Cellular Response Is Size-Dependent. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Tian S, Petros RA, Napier ME, Desimone JM. The Complex Role of Multivalency in Nanoparticles Targeting the Transferrin Receptor for Cancer Therapies. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11306–11313. doi: 10.1021/ja1043177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao Z, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Alexis F, Luptak A, Teply BA, Chan JM, Shi J, Digga E, Cheng J, Langer R, et al. Engineering of Targeted Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy Using Internalizing Aptamers Isolated by Cell-Uptake Selection. ACS Nano. 2012;6:696–704. doi: 10.1021/nn204165v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shokeen M, Pressly ED, Hagooly A, Zheleznyak A, Ramos N, Fiamengo AL, Welch MJ, Hawker CJ, Anderson CJ. Evaluation of Multivalent, Functional Polymeric Nanoparticles for Imaging Applications. ACS Nano. 2011;5:738–747. doi: 10.1021/nn102278w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Z, Al Zaki A, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR, Tsourkas A. Multifunctional Nanoparticles: Cost Versus Benefit of Adding Targeting and Imaging Capabilities. Science. 2012;338:903–910. doi: 10.1126/science.1226338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hak S, Helgesen E, Hektoen HH, Huuse EM, Jarzyna PA, Mulder WJ, Haraldseth O, de Davies CL. The Effect of Nanoparticle Polyethylene Glycol Surface Density on Ligand-Directed Tumor Targeting Studied in Vivo by Dual Modality Imaging. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5648–5658. doi: 10.1021/nn301630n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu F, Zhang L, Teply BA, Mann N, Wang A, Radovic-Moreno AF, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Precise Engineering of Targeted Nanoparticles by Using Self-Assembled Biointegrated Block Copolymers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2586–2591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711714105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakhari A, Baoum A, Siahaan TJ, Le KB, Berkland C. Controlling Ligand Surface Density Optimizes Nanoparticle Binding to Icam-1. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:1045–1056. doi: 10.1002/jps.22342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elias DR, Poloukhtine A, Popik V, Tsourkas A. Effect of Ligand Density, Receptor Density, and Nanoparticle Size on Cell Targeting. Nanomedicine. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu YJ, Zhang Y, Kenrick M, Hoyte K, Luk W, Lu Y, Atwal J, Elliott JM, Prabhu S, Watts RJ, et al. Boosting Brain Uptake of a Therapeutic Antibody by Reducing Its Affinity for a Transcytosis Target. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:84ra44. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tlaxca JL, Rychak JJ, Ernst PB, Prasad KM, Shevchenko TI, Pizzaro T, Rivera-Nieves J, Klibanov AL, Lawrence MB. Ultrasound-Based Molecular Imaging and Specific Gene Delivery to Mesenteric Vasculature by Endothelial Adhesion Molecule Targeted Microbubbles in a Mouse Model of Crohn’s Disease. J Control Release. 2013;165:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight LC. Non-Oncologic Applications of Radiolabeled Peptides in Nuclear Medicine. Q J Nucl Med. 2003;47:279–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agadjanian H, Ma J, Rentsendorj A, Valluripalli V, Hwang JY, Mahammed A, Farkas DL, Gray HB, Gross Z, Medina-Kauwe LK. Tumor Detection and Elimination by a Targeted Gallium Corrole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6105–6110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901531106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbst RS, Shin DM. Monoclonal Antibodies to Target Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Positive Tumors: A New Paradigm for Cancer Therapy. Cancer. 2002;94:1593–1611. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker N, Turk MJ, Westrick E, Lewis JD, Low PS, Leamon CP. Folate Receptor Expression in Carcinomas and Normal Tissues Determined by a Quantitative Radioligand Binding Assay. Anal Biochem. 2005;338:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nair P. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Family and Its Role in Cancer Progression. Current Science. 2005;88:890–898. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatter KC, Brown G, Trowbridge IS, Woolston RE, Mason DY. Transferrin Receptors in Human Tissues: Their Distribution and Possible Clinical Relevance. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:539–545. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prutki M, Poljak-Blazi M, Jakopovic M, Tomas D, Stipancic I, Zarkovic N. Altered Iron Metabolism, Transferrin Receptor 1 and Ferritin in Patients with Colon Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2006;238:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atochina EN, Balyasnikova IV, Danilov SM, Granger DN, Fisher AB, Muzykantov VR. Immunotargeting of Catalase to Ace or Icam-1 Protects Perfused Rat Lungs against Oxidative Stress. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:806–817. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.4.L806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blankenberg S, Barbaux S, Tiret L. Adhesion Molecules and Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muro S, Muzykantov VR. Targeting of Antioxidant and Anti-Thrombotic Drugs to Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2383–2401. doi: 10.2174/1381612054367274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hopkins AM, Baird AW, Nusrat A. Icam-1: Targeted Docking for Exogenous as Well as Endogenous Ligands. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:763–778. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komatsu S, Panes J, Russell JM, Anderson DC, Muzykantov VR, Miyasaka M, Granger DN. Effects of Chronic Arterial Hypertension on Constitutive and Induced Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 Expression in Vivo. Hypertension. 1997;29:683–689. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murciano JC, Muro S, Koniaris L, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Harshaw DW, Albelda SM, Granger DN, Cines DB, Muzykantov VR. Icam-Directed Vascular Immunotargeting of Antithrombotic Agents to the Endothelial Luminal Surface. Blood. 2003;101:3977–3984. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chacko AM, Hood ED, Zern BJ, Muzykantov VR. Targeted Nanocarriers for Imaging and Therapy of Vascular Inflammation. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;16:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calderon AJ, Bhowmick T, Leferovich J, Burman B, Pichette B, Muzykantov V, Eckmann DM, Muro S. Optimizing Endothelial Targeting by Modulating the Antibody Density and Particle Concentration of Anti-Icam Coated Carriers. J Control Release. 2011;150:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamaru M, Tomura K, Sakamoto S, Tezuka K, Tamatani T, Narumi S. Interleukin-1beta Induces Tissue- and Cell Type-Specific Expression of Adhesion Molecules in Vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1292–1303. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.8.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saul JM, Annapragada A, Natarajan JV, Bellamkonda RV. Controlled Targeting of Liposomal Doxorubicin Via the Folate Receptor in Vitro. J Control Release. 2003;92:49–67. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SM, Chen H, O’Halloran TV, Nguyen ST. “Clickable” Polymer-Caged Nanobins as a Modular Drug Delivery Platform. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9311–9320. doi: 10.1021/ja9017336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muzykantov VR, Radhakrishnan R, Eckmann DM. Dynamic Factors Controlling Targeting Nanocarriers to Vascular Endothelium. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13:70–81. doi: 10.2174/138920012798356916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swaminathan TN, Liu J, Balakrishnan U, Ayyaswamy PS, Radhakrishnan R, Eckmann DM. Dynamic Factors Controlling Carrier Anchoring on Vascular Cells. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:640–647. doi: 10.1002/iub.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calderon AJ, Muzykantov V, Muro S, Eckmann DM. Flow Dynamics, Binding and Detachment of Spherical Carriers Targeted to Icam-1 on Endothelial Cells. Biorheology. 2009;46:323–341. doi: 10.3233/BIR-2009-0544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Charoenphol P, Mocherla S, Bouis D, Namdee K, Pinsky DJ, Eniola-Adefeso O. Targeting Therapeutics to the Vascular Wall in Atherosclerosis--Carrier Size Matters. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haun JB, Hammer DA. Quantifying Nanoparticle Adhesion Mediated by Specific Molecular Interactions. Langmuir. 2008;24:8821–8832. doi: 10.1021/la8005844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muro S, Dziubla T, Qiu W, Leferovich J, Cui X, Berk E, Muzykantov VR. Endothelial Targeting of High-Affinity Multivalent Polymer Nanocarriers Directed to Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1161–1169. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.098970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agrawal NJ, Radhakrishnan R. The Role of Glycocalyx in Nanocarrier-Cell Adhesion Investigated Using a Thermodynamic Model and Monte Carlo Simulations. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2007;111:15848–15856. doi: 10.1021/jp074514x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, Weller GE, Zern B, Ayyaswamy PS, Eckmann DM, Muzykantov VR, Radhakrishnan R. Computational Model for Nanocarrier Binding to Endothelium Validated Using in Vivo, in Vitro, and Atomic Force Microscopy Experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16530–16535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu J, Agrawal NJ, Calderon A, Ayyaswamy PS, Eckmann DM, Radhakrishnan R. Multivalent Binding of Nanocarrier to Endothelial Cells under Shear Flow. Biophys J. 2011;101:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, Bradley R, Eckmann DM, Ayyaswamy PS, Radhakrishnan R. Multiscale Modeling of Functionalized Nanocarriers in Targeted Drug Delivery. Curr Nanosci. 2011;7:727–735. doi: 10.2174/157341311797483826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang S, Dormidontova EE. Nanoparticle Design Optimization for Enhanced Targeting: Monte Carlo Simulations. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1785–1795. doi: 10.1021/bm100248e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cu Y, LeMoellic C, Caplan MJ, Saltzman WM. Ligand-Modified Gene Carriers Increased Uptake in Target Cells but Reduced DNA Release and Transfection Efficiency. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garnacho C, Dhami R, Simone E, Dziubla T, Leferovich J, Schuchman EH, Muzykantov V, Muro S. Delivery of Acid Sphingomyelinase in Normal and Niemann-Pick Disease Mice Using Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1-Targeted Polymer Nanocarriers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:400–408. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.133298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chittasupho C, Shannon L, Siahaan TJ, Vines CM, Berkland C. Nanoparticles Targeting Dendritic Cell Surface Molecules Effectively Block T Cell Conjugation and Shift Response. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1693–1702. doi: 10.1021/nn102159g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang S, Park T, Chen X, Dickens G, Lee B, Lu K, Rakhilin N, Daniel S, Jin MM. Tunable Physiologic Interactions of Adhesion Molecules for Inflamed Cell-Selective Drug Delivery. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3487–3498. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunawan RC, Auguste DT. Immunoliposomes That Target Endothelium in Vitro Are Dependent on Lipid Raft Formation. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:1569–1575. doi: 10.1021/mp9003095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rossin R, Muro S, Welch MJ, Muzykantov VR, Schuster DP. In Vivo Imaging of 64cu-Labeled Polymer Nanoparticles Targeted to the Lung Endothelium. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:103–111. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jayagopal A, Russ PK, Haselton FR. Surface Engineering of Quantum Dots for in Vivo Vascular Imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1424–1433. doi: 10.1021/bc070020r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shao X, Zhang H, Rajian JR, Chamberland DL, Sherman PS, Quesada CA, Koch AE, Kotov NA, Wang X. 125i-Labeled Gold Nanorods for Targeted Imaging of Inflammation. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8967–8973. doi: 10.1021/nn203138t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Muzykantov VR, Atochina EN, Ischiropoulos H, Danilov SM, Fisher AB. Immunotargeting of Antioxidant Enzyme to the Pulmonary Endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5213–5218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Surti S, Karp JS, Perkins AE, Cardi CA, Daube-Witherspoon ME, Kuhn A, Muehllehner G. Imaging Performance of a-Pet: A Small Animal Pet Camera. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2005;24:844–852. doi: 10.1109/tmi.2005.844078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bell GI, Dembo M, Bongrand P. Cell Adhesion. Competition between Nonspecific Repulsion and Specific Bonding. Biophys J. 1984;45:1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, Wojcikiewicz E, Moy VT. Force Spectroscopy of the Leukocyte Function-Associated Antigen-1/Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 Interaction. Biophys J. 2002;83:2270–2279. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73987-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roux B. The Calculation of the Potential of Mean Force Using Computer Simulations. Comput Phys Commun. 1995;91:275–282. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.