Abstract

In the mammalian testis, extensive restructuring takes place across the seminiferous epithelium at the Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell interface during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis, which is important to facilitate changes in the cell shape and morphology of developing germ cells. However, precise communications also take place at the cell junctions to coordinate the discrete events pertinent to spermatogenesis, namely spermatogonial renewal via mitosis, cell cycle progression and meiosis, spermiogenesis, and spermiation. It is obvious that these cellular events are intimately related to the underlying actin-based cytoskeleton which is being used by different cell junctions for their attachment. However, little is known on the biology and regulation of this cytoskeleton, in particular its possible involvement in endocytic vesicle-mediated trafficking during spermatogenesis, which in turn affects cell adhesive function and communication at the cell-cell interface. Studies in other epithelia in recent years have shed insightful information on the intimate involvement of actin dynamics and protein trafficking in regulating cell adhesion and communications. The goal of this critical review is to provide an updated assessment of the latest findings in the field on how these complex processes regulate spermatogenesis. We also provide a working model based on the latest findings in the field to provide our thoughts on an apparent complicated subject, which also serves as the framework for investigators in the field. It is obvious that this model will be rapidly updated when more data are available in future years.

Keywords: Testis, spermatogenesis, seminiferous epithelial cycle, actin cytoskeleton, ectoplasmic specialization, protein trafficking

1. Introduction

In mammals, spermatogenesis is a highly complicated biological process that takes place in the epithelium of the seminiferous tubule – the functional unit of the testis, which produces >100 million spermatozoa per day in a human male since puberty (Cheng and Mruk, 2002; Cheng and Mruk, 2010; de Kretser and Kerr, 1988; Sharpe, 1994). This process is under the regulation of LH and FSH released from the pituitary gland under the influence of GnRH from the hypothalamus, and also tightly controlled by testosterone and estradiol-17β that produced locally in the testis to serve as the feedback regulatory loop, in the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis (Carreau and Hess, 2010; Cheng and Mruk, 2012b; de Kretser and Kerr, 1988; Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; O'Donnell et al., 2001; O'Donnell et al., 2006; Steinberger, 1971; Winters and Moore, 2004; Winters and Moore, 2007). Anatomically, the seminiferous epithelium is divided into the basal and the adluminal (apical) compartment by the blood-testis barrier (BTB) (Figure 1). Thus, meiosis I/II to be followed by post-meiotic development of spermatids via spermiogenesis all take place in a specialized microenvironment in the adluminal compartment behind the BTB and segregated from the systemic circulation. The BTB is located near the basement membrane of the seminiferous epithelium, between adjacent Sertoli cells, and constituted by desmosome and coexisting tight junction (TJ), basal ectoplasmic specialization (ES, a testis-specific atypical AJ), and gap junction (GJ) (Cheng and Mruk, 2012b; Franca et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Pelletier, 2011; Wong et al., 2008a). During the seminiferous epithelial cycle, the BTB remains intact so that germ cell-specific antigens, some of which appear transiently in post-meiotic spermatids during spermiogenesis, can be sequestered from the immune responding cells in the systemic circulation, in order to avoid the production of antibodies against “self-antigens”, many of which are oncogenes known as cancer/testis antigens (Cheng et al., 2011b). At stage VIII of the epithelial cycle, the BTB, however, undergoes extensive restructuring to facilitate the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes residing at the basal compartment, traversing the barrier to enter the adluminal compartment for further development (Russell, 1977). Interestingly, even at the time of restructuring, the barrier integrity at the BTB is maintained via a unique mechanism in which “new” TJ-barrier is assembled behind the spermatocytes in transit before the “old” TJ-barrier is disassembled (Cheng and Mruk, 2010; Cheng and Mruk, 2012a; Mruk and Cheng, 2011) as earlier shown in a lanthanum study that tracked the BTB integrity (Mruk and Cheng, 2008; Yan et al., 2008). Besides BTB restructuring, developing germ cells including spermatocytes and all steps of spermatids also traverse progressively across the epithelium from near the basement membrane towards to the luminal edge of the seminiferous tubule, and elongating spermatids also move “up” and “down” of the epithelium during spermiogenesis (Cheng and Mruk, 2012b; Mruk et al., 2008; Parvinen, 1982). This cyclic restructuring of the BTB and the cyclic events of germ cell movement across the epithelium are undoubtedly crucial to spermatogenesis, but they also involve extensive restructuring of cell junctions at the Sertoli-Sertoli and Sertoli-germ cell interface in particular the underlying cytoskeleton of these cell junctions.

Fig.1. Schematic drawing illustrating the distribution of actin filament bundles in the seminiferous epithelium of adult rat testis and their relationship with developing germ cells and different cell junctions during spermatogenesis.

The BTB physically divides the seminiferous epithelium into the basal and the adluminal (apical) compartment. The BTB is constituted by desmosomes, and coexisting tight junctions (TJs), basal ectoplamic specializations [basal ESs, a testis-specific adherens junction (AJ)], and gap junctions (GJs). The most notable ultrastructural feature of the BTB is the presence of actin filament bundles that lie perpendicular to the apposing Sertoli-Sertoli (basal ES) or Sertoli-spermatid (apical ES) plasma membranes sandwiched between the cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum and the apposing plasma membranes, known as the ES. At the apical ES, the actain filament bundles, however, are restricted to the Sertoli cell, not the apposing germ cells. As discussed in the text, during the seminiferous epithelial cycle, the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes across the BTB and the releasing of developed elongated spermatids involve a simultaneous restructuring of cell junctions at the apical ES and the BTB the lie at the opposite ends of the epithelium. This process alongside with spermiogenesis are intimately related to changes in organization and/or confirguration of the actin filament bundles at the ES. [Colored version of this figure can be found in the on-line version of this issue of the journal]

Recent studies have shown that the constitution and cyclic restructuring of the adhesion devices at the cell-cell interface in the testis are closely related to the restricted and localized actin cytoskeleton organization in the seminiferous epithelium. At the basal ES, tightly packed actin filament (F-actin) bundles, that lie perpendicular to the Sertoli cell plasma membrane and sandwiched between the apposing Sertoli cell membranes and cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum and confers to the unusual tightness of the BTB among other blood-tissue barriers in mammals, must undergo extensive re-organization when proleptotene spermatocytes traverse the BTB at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (Cheng and Mruk, 2010; Cheng and Mruk, 2012b; Lie et al., 2010a; Vogl et al., 2000). On the other hand, in order to facilitate spermatids migration and to maintain spermatid orientation and polarity, the actin bundles at the apical ES also undergo continuous reorganization from a “bundled” to a “de-bundled” state, such as forming a highly branched actin network at late stage VII of the cycle, which initiates at the concave side of elongating/elongated spermatid head. Studies have shown that F-actin bundles at the apical and basal ES are maintained and regulated by actin binding proteins (ABPs), such as actin bundling and barded end-capping proteins [e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8)] (Lie et al., 2009a), branched-actin polymerization proteins [e.g., actin related protein 3 (Arp3)] (Lie et al., 2010b), actin filament cross-linking proteins (e.g., filamin A) (Su et al., 2012a; Su et al., 2012b), and actin binding/regulatory protein recruiters (e.g., drebrin E that recruits Arp3, but not Eps8, to specific domain in the seminiferous epithelium, such as apical ES to induce branched actin polymerization) (Cheng and Mruk, 2011a; Li et al., 2011).

Besides serving as a“gate”and a“fence”in the testis to restrict paracellular and transcellular exchange of water and other biomolecules between the systematic circulation or the basal compartment and the apical compartment, the BTB also confers cell polarity via differential distribution of functional proteins along the apical and basolateral membrane domains of the Sertoli cell epithelium (Wong and Cheng, 2009). To date, the homologs of the three polarity protein complexes that were firstly found in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, namely the Crumb (CRB) protein complex, the partitioning-defective (PAR) protein complex, and the Scribble protein complex, have been studied in the rat testis and were shown to play important roles in Sertoli cell and spermatid adhesion and polarity, maintaining a functional BTB and apical ES via their effects, at least in part, on the actin filament bundles at these sites in the epithelium during spermatogenesis (Su et al., 2012c; Su et al., 2012d; Wong et al., 2008b; Wong et al., 2010). For instance, some of the polarity proteins and their associated proteins, such as Par3/Par6, Scribble, Lgl, 14-3-3, and Cdc42, were found to participate in cell junction protein recruitment and protein endocytosis, which are likely mediated by changes in F-actin re-organization during BTB restructuring and spermiogenesis.

In this review, we first summarize recent findings in the field regarding the involvement and the mechanistic function of different actin binding/regulatory and polarity proteins during spermatogenesis, to be followed by a critical evaluation on how these two types of molecules exert their intriguing effects to regulate actin dynamics and protein trafficking so that extensive restructuring can take place across the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis. We also provide a new biochemical model to explain how the cellular events that take place at the BTB and the apical ES are coordinated and regulated during spermatogenesis.

2. Actin-based cytoskeleton in the seminiferous epithelium

2.1. Overviews of actin organization in the seminiferous epithelium

In polarized epithelial cells, contractile actomyosin ring of actin filaments together with the adherens junction that constitute the typical zonula adhesion plaque is located immediately behind the TJ, segregated as discrete ultrastructures (Cavey et al., 2008; Mege et al., 2006). In the mammalian testis, TJs that contribute significantly to the barrier function at the BTB, however, coexist with unique actin-rich structure ectoplasmic specialization (ES) at the Sertoli cell-cell interface near the basal compartment known as the basal ES (Cheng and Mruk, 2012b; Franca et al., 2012; Pelletier, 2011) (Figure 1). However, ES is also found in the adluminal (apical) compartment known as apical ES at the Sertoli-spermatid interface (step 8–19 spermatids in the rat testis) which will transform into a transitional ultrastructure formerly designated as tubulobulbar complex (TBC) (Cheng and Mruk, 2010; Cheng and Mruk, 2011b; Vogl et al., 2008), which represents apical ES undergoing extensive endocytic vesicle-mediated protein endocytosis (Vaid et al., 2007; Young et al., 2009a; Young et al., 2009b), and the organized actin filament bundles are also replaced with the branched actin network (Russell, 1979; Vogl et al., 2008), thereby de-stabilizing the apical ES to facilitate intracellular protein trafficking. Thus, apical ES proteins from the degenerating apical ES during spermiation can be recycled to assemble newly developed apical ES that arises from spermiogenesis (Cheng and Mruk, 2010). These testis-specific ES, namely the basal and the apical ES, exhibit distinctly different pattern of organization of F-actin from all other epithelia and are unique to the testis.

Studies by electron microscopy have shown that the ES is a tripartite ultrastructure in which actin filament bundles that lie perpendicular to the Sertoli cell plasma membrane are sandwiched in-between cisternae of endoplasmic reticulum and the: (i) apposing Sertoli cell plasma membranes (at the basal ES) or (ii) apposing Sertoli-spermatid plasma membranes (at the apical ES) (Cheng and Mruk, 2010; Cheng and Mruk, 2012b; Vogl et al., 2000) (Figure 1). The apical ES shares the same ultrastructural features as of the basal ES, except that these unique actin bundles are restricted to the side of the Sertoli cell, and there is no identifiable ultrastructures at or near the plasma membrane in the elongating/elongated spermatid (steps 8–19) (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Russell and Peterson, 1985; Russell et al., 1990; Vogl et al., 2008; Vogl et al., 2000). Interestingly, recent studies have shown that these spermatids express similar cell adhesion integral membranes proteins as of the Sertoli cell and are localized to the apical ES site (e.g., N-cadherin, E-cadherin, nectin-2, nectin-3) and their associated adaptors (e.g., α-/β-catenin, afadin, vinculin) and regulatory proteins (e.g., c-Src, ILK, p-FAK-Tyr397, p-FAK-Tyr407) without the underlying network of actin filament bundles (Cheng and Mruk, 2002; Cheng and Mruk, 2010; Lie et al., 2012), and thereby invisible even under electron microscopy. Furthermore, these spermatids express unique proteins that are not found in the Sertoli cell at the apical ES, such as nectin-3, laminin-α3, -β3, and -γ3 chains (Koch et al., 1999; Ozaki-Kuroda et al., 2002; Yan and Cheng, 2006). This unique feature perhaps is physiologically necessary that provides an efficient mechanism to induce rapid “adhesion” and “de-adhesion” at the Sertoli-spermatid interface during spermiogenesis since the “break-down” of adhesion protein complexes, such as nectin-3-afadin and laminin-α3/β3/γ3 with their counterparts, namely nectin-2/-3-afadin and α6β1-integrin residing in Sertoli cells, do not involve “re-organization” of the extensive F-actin since spermatids are metabolically quiescence cells when compared to the Sertoli cells. Recent studies have shown that many of the integral membrane proteins at the ES use actin for attachment in studies by co-immunoprecipitation with and without the use of a chemical cross-linker (Lee et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004). However, unlike F-actin found in other epithelial cells, such as fibroblasts, keratinocytes or macrophages, F-actin bundles at the ES are not contractile (Vogl and Soucy, 1985; Vogl et al., 2000), and spermatids per se are not motile cells during spermiogenesis but rely on the cytoplasmic processes of the Sertoli cells, which in conjunction with the polarized microtubule network that serves as the track, for the “up-and-down” movement across the epithelium during the epithelial cycle (Amlani and Vogl, 1988; Redenbach and Vogl, 1991; Wang et al., 2008). Nonetheless, this unique arrangement of actin filament bundles at the ES also confers its remarkable adhesive strength, which was previously shown to be significantly stronger than desmosome at the Sertoli-pre-step 8 spermatid interface when the force required to “breakdown” these junctions were quantified (Wolski et al., 2005), even though desmosome, such as in skin, is considered to be one of the strongest anchoring junctions (Green and Simpson, 2007; Green et al., 2010; Simpson et al., 2011).

In this context, it is of interest to note that in stage VII of the epithelial cycle, on the ventral (or concave) side of the spermatid heads, the orderly packed F-actin bundles in Sertoli cells at the ES are replaced by highly branched networks, creating tubular protrusions from the plasma membrane of spermatid heads in steps 18–19 spermatids into the associated Sertoli cell membrane formerly designated apical TBC which are visible under fluorescence and also electron microscopy (Russell, 1979; Vogl et al., 2008). Subsequent studies have shown that these tubulobulbar complexes represent “giant” endocytic vesicles composed of proteins involved in the formation of endocytic vesicles, such as dynamin III (Vaid et al., 2007), clathrin, cortactin, and N-WASP (Lie et al., 2010b; Young et al., 2009a; Young et al., 2009b). In fact, recent studies have shown that proteins that are necessary to induce branched actin polymerization, such as Arp3, are up-regulated at the concave side of the spermatid heads at stage VII of the epithelial cycle (Lie et al., 2010b), which is likely being used to induce changes in the F-actin configuration at the site from its “bundled” to its “de-bundled” and “branched” state to facilitate protein endocytosis, so that apical ES proteins (e.g., integrins, laminins, nectins) can be transcytosed and recycled to the newly formed apical ES as the result of spermiogenesis, and to prepare the “old” apical ES to undergo degeneration to facilitate spermiation (Figure 2). While the biochemical and molecular mechanism(s) underlying the shifting of F-actin network from its “bundled” to “branched” state during the epithelial cycle remains largely unknown, multiple actin-binding and regulatory proteins must be involved. For instance, it was shown that drebrin E, an actin binding proteins also found in Sertoli cells at the concave side of the spermatid head at stage VII tubules, was also up-regulated in parallel to Arp3, and drebrin E was found to have high affinity for Arp3, illustrating it may be used to recruit Arp3 to the site to facilitate the formation of endocytic vesicles for protein endocytosis (Li et al., 2011). In fact, recent studies in other epithelia have demonstrated an intimate relationship between actin dynamics and endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking (Anitei and Hoflack, 2011; Gonnord et al., 2012). For instance, Arp2/3 is also involved in endosome dynamics necessary for the maintenance of Par-mediated apico-basal polarity in C. elegans (Shivas and Skop, 2012). More important, protein endocytosis is now known to be more than just a cellular mechanism to regulate protein/receptor recycling, instead it is part of the integrated network of cell signaling (Gonnord et al., 2012). In this section, we provide a critical evaluation of recent findings in the field, providing some insightful thoughts on this event.

Fig.2. Effects of actin-regulating and -binding proteins, Arp2/3 complex, Eps8, and drebrin E on actin cytoskeleton organization to facilitate BTB restructuring during the epithelial cycle.

(A) Eps8 acts as an actin bundling protein via its association with insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate (IRSp53). The Arp2/3 complex, however, is composed of 7 subunits (i.e., Arp2, Arp3, and ARPC1–5) which can induce branched actin polymerization (i.e., inducing actin filaments from “bundled” configuration to “branched’ actin network) after activated by N-WASP and WAVE. Thus, these two important actin regulatory proteins found in the testis are known to confer actin filaments in a “bundled” or a “de-bundled and branched” state at the apical and basal ES to facilitate ES restructuring. (B, C) The highly restricted spatiotemporal but differential expression of Eps8, Arp3, and drebrin E (an actin-binding protein that recruits Arp3 to the ES during the epithelial cycle to induce branched actin polymerization and then ES restructuring) in the seminiferous epithelium facilitate the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes and spermiation at the apical ES (B) and the apical ES at the BTB (C), respectively, by affecting the status or organization/configuration of actin filament bundles. Although lacking intrinsic activity to regulate actin filament organization directly, drebrin E functions by recruiting Arp3 to the ES for remodeling of F-actin. The “de-bundling” of actin filament at the apical and basal ES by activated Arp2/3 complex is accompanied by a disruption of ES, which is mediated, at least in part, via an increase in protein endocytosis of the component proteins, which are either targeted to endosome-mediated degradation or recycling back to cell-cell interface where the “new” junctions are arisen during the epithelial cycle. [Colored version of this figure can be found in the on-line version of this issue of the journal]

2.2. Actin binding and regulating proteins in regulating actin filament bundles at the ES during spermatogenesis

Actin is the most abundant cytoskeleton besides the intermediate- and microtubule-based cytoskeletons in eukaryotic cells, approximately half of which is kept in monomeric form as globular actin (G-actin) and the other half exists in a polymer form as filamentous actin (F-actin). Each actin filament has intrinsic polarity, possessing a fast-growing end (the barbed end) and a slow-growing end (the pointed end) (Pellegrin and Mellor, 2007). The dynamics of actin are composed of a series of biochemical events which include polymerization, depolymerization, bundling, nucleation, branching cross-linking, severing, and capping, that require the participation of an array of actin-binding and regulatory proteins (Table 1) (Cheng and Mruk, 2011a; Cheng et al., 2011a; Lie et al., 2010a). Interestingly, some of these proteins that regulate actin dynamics also contribute to endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking (Anitei and Hoflack, 2011; Mooren et al., 2012), which can in turn affects cell adhesion function, facilitating spermatid movement across the epithelium during the epithelial cycle (Cheng and Mruk, 2011b; Lie et al., 2010a). Recent studies have shown that the configuration of actin filaments at the ES in the testis is regulated by two unique mechanisms discussed herein.

Table 1.

Actin-binding proteins of different functions in the testis.

| Protein |

Mr

* (kDa) |

Effects on actin | Localization in testis |

Role in spermatogenesis |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eps8 | 97 | Actin capping and bundling | Apical ES, BTB | Actin bundle formation | (Lie et al., 2009a) |

| Espin | 110 | Actin bundling | Apical ES, BTB | Actin bundle formation | (Bartles et al., 1996) |

| α-Actinin | 100 | Actin bundling | BTB | Actin bundle formation | (Yazama et al., 1991) |

| Fascin | 55 | Actin bundling | Elongating spermatid | Germ cell morphogenesis | (Tubb et al., 2002) |

| Profilin III | 15 | Actin monomer binding | Spermatid nuclear | Germ cell morphogenesis | (Hara et al., 2008) |

| Cofilin | 19–21 | Actin depolymerization | Apical TBC | Actin turnover | (Guttman et al., 2004) |

| Arp3 | 45 | Actin nucleation and branching | Apical TBC, basal TBC | Actin network formation | (Lie et al., 2010b) |

| cortactin | 80 | Arp2/3 actinvation | Apical TBC | Actin network formation | (Young et al., 2009b) |

| mDia1/2 | 140 | Actin nucleation | Cytoplasm | Not determined | (Mironova and Millette, 2008) |

| Filamin A | 280 | Actin branching | Developing BTB | Actin network organization during BTB formation | (Su et al., 2012b) |

This apparent Mr denoted here is based on studies in the testis by SDS-PAGE using the corresponding specific antibodies.

2.2.1. Regulation of ES via restricted spatiotemporal expression of Arp3 and Eps8 during the epithelial cycle

Eps8 can act as an actin bundling or barbed end capping protein via its association with specific binding partners. For instance, its interaction with Abi-1 (Abelson interacting protein-1), IRSp53 (insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate), or Abi-1 and Sos1 (son of sevenless 1) elicits its actin barbed end capping activity, actin bundling activity, or activation of Rac GTPase (which in turn modulates lamelliopodia), respectively (Ahmed et al., 2010; Cheng and Mruk, 2011b; Hertzog et al., 2010; Vaggi et al., 2011) (Figure 2). The Arp2/3 protein complex, however, is an actin nucleating machinery that induces branched actin polymerization on preexisting actin filaments that yields a branched actin network following its activation by Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) family proteins [e.g., neuronal WASP (N-WASP), WASP family verprolin-homologous protein (WAVE)], ARPC1–5 (Arp2/3 complex subunits 1–5), cortactin (Cheng and Mruk, 2011b; Insall and Machesky, 2009; Weaver et al., 2003; Weaver et al., 2002) (Figure 2). Thus, Eps8 and Arp2/3 complex and their associated binding partners, if found in the testis, can regulate actin dynamics by conferring the actin filament “bundled” or “de-bundled/branched” state at the apical and basal ES depending on their stage-specific and spatiotemporal expression at these sites during the epithelial cycle. Indeed, recent studies have demonstrated the presence and expression of Eps8 and Arp3, as well as their corresponding binding partners (e.g., Sos1, IRSp53 and Abi-1 for Eps 8; N-WASP and cortactin for Arp3) by Sertoli and/or germ cells in the rat testis (Lie et al., 2009a; Lie et al., 2010b).

In stage V-VI tubules, Eps8 is highly expressed at the apical ES and the BTB when F-actin bundles are needed to maintain strong cell adhesive function at these sites (Lie et al., 2009a). Beginning at stage VII, when apical ES undergoes morphological transformation to prepare for spermiation (such as endocytosis of apical ES proteins to “reduce” spermatid adhesive function) that takes place in stage VIII, the expression of Eps8 in Sertoli cells at the apical ES shifted to the concave side of the elongated spermatid head and its expression began to decrease considerably, coinciding with the appearance of the apical TBC (Lie et al., 2009a; O'Donnell et al., 2011; Russell, 1979; Young et al., 2009a), an ultrastructure representing the degenerating (or disassembling) apical ES (Cheng and Mruk, 2010). At stage VIII, Eps8 is diminished at both the apical ES and the BTB to a level virtually undetectable, and this down-regulation thus contributes to the formation of a “de-bundled” F-actin state at the ES, leading to junction disassembly at the apical ES to facilitate spermiation and BTB restructuring to induce the transit of preleptotene spermatocytes across BTB (Lie et al., 2009a). On the other hand, Arp3 of the Arp2/3 complex exhibits a distinctly different expression pattern at the BTB in contrast to Eps8, instead of a down-regulation, the Arp3 expression exhibited a considerably surge at stage VIII, possibly being used to induce the formation of branched actin network to facilitate BTB restructuring (Lie et al., 2010b). At the apical ES in stage VII tubules, Arp3 is also localized predominantly at the concave side of the spermatids head to facilitate apical ES disassembly, such as by reorganizing the actin filament bundles, converting to a branched network via its intrinsic branched actin-polymerization activity (Lie et al., 2010b). At stage VIII, when spermiation takes place and apical ES ceases to undergo restructuring, Arp3 diminishes to a virtually undetectable level (Lie et al., 2010b). Thus, it is via this unusual restrictive spatiotemporal up- and down-regulation of the actin bundling/barbed end capping protein Eps8 that favors actin filament bundles, and the branched-actin polymerizing protein Arp3 that favors branched actin network, the actin configuration that facilitates spermatid adhesion or de-adhesion can be efficiently and tightly regulated during the epithelial cycle (Figure 2). This notion is also supported by a recent study using a genetic model in which N-WASP was selectively knockout in Sertoli cells (cKO), and these mice were found to be infertile versus the corresponding wild-type even though meiosis was not perturbed but round spermatids failed to develop into functional spermatozoa via spermiogenesis because of the disruption of the actin dynamics (Rotkopf et al., 2011). These findings also illustrate how the restrictive spatiotemporal expression of these two actin regulatory proteins can coordinate the events of spermiation and BTB restructuring that occur at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle. Interestingly, a recent report has shown that the restrictive spatiotemporal expression of Arp3, but not Eps8, at the ES is regulated, at least in part, by the similar restrictive expression of p-FAK-Tyr407, since Arp3 was found to be structurally interacted with p-FAK-Tyr407 (Lie et al., 2012), which may recruit additional regulatory proteins, such as mTORC1 (Mok et al., 2012b) to the site to elicit the formation of branched actin network.

2.2.2. Cooperation with other actin regulatory proteins

2.2.2.a. Drebrin E (developmentally regulated brain protein E)

Drebrin E is a member of the drebrin family of actin-binding proteins that regulate various cellular functions, including actin bundles formation (Shirao et al., 1994), dendritic spine building and gap junction stabilization (Majoul et al., 2007), actin remodeling (Biou et al., 2008), and lamellipodia and filopodia formation (Peitsch et al., 2001). Although lacking intrinsic activity in directly regulating actin dynamics (Grintsevich et al., 2010; Hayashi et al., 1999; Ishikawa et al., 1994), drebrins regulate F-actin network via competitive binding with other actin-binding proteins (e.g., α-actinin, fascin, and tropomyosin) via its actin binding domain (Hayashi et al., 1999; Li et al., 2011; Peitsch et al., 1999; Shirao, 1995). In the rat testis, the stage-specific and spatiotemporal expression of drebrin E at the apical ES and the BTB closely mimics that of Arp3 (Li et al., 2011). More interestingly, drebrin E structurally interacts with Arp3, perhaps recruiting Arp3, to the ES to induce F-actin remodeling, creating the branched actin network to favor apical ES disruption at spermiation, and BTB restructuring at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (Cheng and Mruk, 2011a; Li et al., 2011) (Figure 2). This interaction between drebrin E and Arp3 was shown to induced following treatment of TGFβ3 and TNFα (Li et al., 2011), which are also known to be expressed stage-specifically by Sertoli and germ cells and participate in endocytic-vesicle mediated protein trafficking to prepare the restructuring of the BTB and apical ES at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (Li et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2006). These results thus suggest that drebrin E may serve as a platform to recruit other actin regulatory proteins to the apical ES and the BTB for the restructuring of actin filament bundles to accommodate changes in spermatid shape and spermatid movement during spermiogenesis, and BTB restructuring to facilitate preleptotene transit at the BTB, respectively.

2.2.2.b. Filamin A

Filamin A, formerly known as actin-binding protein 280 (ABP280) (Hartwig and Stossel, 1975), is a nonmuscle actin filament cross-linker that participates in F-actin network organization and cell adhesion (Nakamura et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2010). Moreover, filamin A is known to serve as scaffold and binding partner for multiple proteins, many of which are intimately related to spermatogenesis, which include vinculin, 14-3-3, JNK, ROCK, Pak1, PKC, Smads, caspase, caveolin-1 (Nakamura et al., 2011; Whitmarsh, 2009). Recent studies in the rat testis have shown that filamin A structurally interacts with JAM-A, a TJ-integral membrane protein at the BTB, in Sertoli cells cultured in vitro with an established function TJ-permeability barrier (Su et al., 2012b). Furthermore, a knockdown of FLNa by RNAi was found to partially perturb the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier both in vitro and in vivo, which are accompanied by a mis-localization of junction proteins (e.g., JAM-A/ZO-1, N-cadherin/β-catenin) and a dis-organization of F-actin network in which F-actin failed to localize at the Sertoli cell-cell interface, thereby disrupting the TJ-barrier (Su et al., 2012b), since integral membrane proteins could no longer be recruited to maintain the TJ-fibrils. This thus suggests the notion that filamin A may be important to recruit proteins to the ES via its effects on actin dynamics during spermatogenesis. Indeed, filamin A was found to prompt the recruitment of proteins to the basal ES at the BTB during development since its knockdown in neonatal rats in vivo by RNAi was found to delay the assembly of the BTB during post-natal development in which the F-actin network was disrupted so that integral membrane proteins (e.g., JAM-A, N-cadherin) failed to localize properly at the BTB (Su et al., 2012b).

In short, these observations support the notion that actin dynamics in the testis are regulated by multiple regulators, such as drebrin E and filamin A, that confer the optimal actin configuration to maintain the homeostasis of the ES during spermatogenesis via their intrinsic activity or by recruiting other partner proteins to the site.

3. Regulation of actin dynamics in the testis during spermatogenesis by some unlikely partners - polarity proteins

Establishment of cell polarity in epithelia, including the seminiferous epithelium, is crucial for maintaining cell morphology and function. The presence of apico-basal polarity in any cell epithelium requires precisely targeting of membrane and peripheral proteins to either apical or basal lateral membrane domain which are physically separated by the TJs that serve as a selectively permeable barrier to paracellular and transcellular diffusion of molecules under physiological and pathophysiological conditions (Boggiano and Fehon, 2012; Ellenbroek et al., 2012; Iden and Collard, 2008; Mogilner et al., 2012; Tepass, 2012). Recent studies, however, have demonstrated that polarity proteins are not only associated with TJs in determining cell polarity, but they are also involved in vesicular transport of integral membrane proteins (Balklava et al., 2007; Iden et al., 2006; Macara and Spang, 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Wells et al., 2006). Indeed, studies have shown that many polarity proteins are components of the cell junctions in the seminiferous epithelium, participating in polarity maintenance and cell junction restructuring during spermatogenesis (Table 2) (Su et al., 2012c; Wong et al., 2008b; Wong et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2009). However, unlike polarity proteins in other epithelia in which Par- and Crumb-based protein complexes are located at or close to the TJ whereas Scribble-based complex is at the baso-lateral region of the cell epithelium, displaying mutual exclusive distribution pattern; Par-based proteins (e.g., Par3, Par6, 14-3-3) and Crumb-based proteins (e.g., Patj, Pals1) are found at both the apical ES and the basal ES at the BTB (Wong et al., 2008b; Wong et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2009), whereas the Scribble-based proteins (e.g., Scribble) were found mostly at the BTB (Su et al., 2012c). Also, unlike the actin-associated proteins that are found mostly at the concave side of the elongating spermatids at the apical ES, such as Arp3 and Eps8 (Lie et al., 2009a; Lie et al., 2010b), polarity proteins present at the apical ES, such as Par6 and 14-3-3, are localized at the convex side of the cell (Wong et al., 2008b; Wong et al., 2009). A recent report has shown that these polarity proteins, in particular the Scribble complex, are also regulators of actin organization in the seminiferous epithelium (Su et al., 2012c).

Table 2.

Components of polarity protein complexes in the rat testis

| Polarity complex |

Components | Mr (kDa) * | Distribution and expression in testis |

Known interacting proteins |

Role in protein trafficking in testis |

Role in actin organization in testis |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Par | Par3 | 100/150/180 | Apical ES and the BTB, with a decline in stage VIII tubules | Cdc42 Src 14-3-3 JAM-C Pals1 Lgl |

Stabilize JAM-A and α-catenin at cell-cell interface | Not determined | (Wong et al., 2008b) |

| Par6 | 37/45/60 | ||||||

| aPKC | 80 | ||||||

| Crb | Crb3 | 24 | Mainly in germ cells, detectable in Sertoli cells | JAM-C Lin-7 Par6 |

Not determined | Not determined | (Kamberov et al., 2000; Makarova et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2008b) |

| Pals1 | 77 | ||||||

| Patj | 55/100 | ||||||

| Scribble | Scribble | 250 | BTB, with an increase in stage VIII tubules | ZO-2 aPKC myosin II p32 |

Endocytosis of occludin and β-catenin | Re-distribution of F-actin at the BTB and apical ES | (Bialucha et al., 2007; Chlenski et al., 2000; Su et al., 2012c) |

| Lgl | 130 | ||||||

| Dlg | 130 |

This apparent Mr denoted here is mostly based on studies in the testis by SDS-PAGE using the corresponding specific antibodies.

3.1. The partitioning-defective complex (Par)

3.1.1. Par3/Par6

The Par proteins were first identified in Caenorhabditis elegans zygote as regulators of anterior-posterior polarity which also share similar functionality in vertebrates (Goldstein and Macara, 2007; Noatynska and Gotta, 2012; Su et al., 2012d; Wong and Cheng, 2009). Mammalian Par homologs, namely Par3 and Par6, were found to form an evolutionarily conserved protein complex with Cdc42, atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) and several other components, involved in regulating epithelial cell polarity (Assemat et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008a). In mammalian cell epithelia, Par6 is a key adaptor that associates with Par3, Cdc42/Rac1 and aPKC and recruits these proteins to induce TJ formation, and thus, the Par-based protein complex is restricted to the apical region of a cell epithelium, close to the TJ (Joberty et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Suzuki et al., 2001) (Figure 3). In neuroepithelial cells of embryonic telencephalon, Par3 was detected to co-localize and interact directly with AJ protein nectin-3, which was considered to be crucial in targeting Par3 to AJ (Manabe et al., 2002; Takekuni et al., 2003). In endothelial cells, a direct association was also found between vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) and a distinct Par complex (Iden et al., 2006). Some recent studies have probed the presence and function of Par protein complex in Sertoli and germ cells (Fujita et al., 2007; Gliki et al., 2004; Lui et al., 2003b; Wong et al., 2008b). Using dual-labeled immunofluorescence analysis, Par6 was shown to be co-localized with occludin, N-cadherin, and γ-catenin at the BTB near the basement membrane in the seminiferous epithelium, and also with JAM-C at the apical ES in a stage-specific manner at stage V-VIII, but its expression at these sites were found to be down-regulated at stage VIII during BTB restructuring and spermiation (Wong et al., 2008b). In addition, the in vitro knockdown of either Par3 or Par6 by RNAi using specific siRNA duplexes in Sertoli cells with an established TJ-permeability barrier that mimicked the BTB in vivo led to a redistribution of JAM-A and α-catenin at the Sertoli cell-cell interface, with these proteins moved from the cell surface into the cell cytosol, thereby destabilizing the TJ permeability barrier (Wong et al., 2008b). These findings also implicate that changes of protein localization and/or distribution in the Sertoli cell epithelium following the knockdown of either Par3 or Par6 that eventually perturbs the TJ barrier function is likely the result of an increase in endocytic-vesicle mediated protein endocytosis, perhaps mediated, at least in part, by changes in the underlying actin organization at the basal ES. Furthermore, using testes from adjudin-treated rats in which adjudin is known to induce germ cell depletion from the seminiferous epithelium as a result of apical ES degeneration without perturbing the BTB function (Mok et al., 2012a; Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Siu et al., 2005; Su et al., 2010; Yan and Cheng, 2005), a truncation and “de-bundling” of actin filaments at the apical ES were detected (Wong et al., 2008b). Also, a loss of Par6 staining was detected at the apical ES which was associated with misoriented spermatids before their depletion, illustrating a loss of spermatid polarity (Wong et al., 2008b). Remarkably, studies by using co-immunoprecipatation, a tighter association between Par6/Pals1 and Src after adjudin treatment was detected which sequestered Par6/Pals1 from their association with JAM-C (Wong et al., 2008b), and an earlier report suggested that JAM-C was crucial to form heterophilic interaction with JAM-B to confer adhesion function at the apical ES (Gliki et al., 2004). Thus, such changes in association of Par6/Pals1 and Src versus Par6/Pals1 and JAM-C provides an efficient mechanism to regulate spermatid adhesion at the apical ES (Wong et al., 2008b). In short, these findings illustrate that the Par-based polarity proteins are working in concert with the Crumbs-based proteins (e.g., Patj, Pals1) and non-receptor protein kinases (e.g., c-Src) that confer cell adhesion besides their involvement in spermatid polarity. More important, such changes in cell adhesion mediated by Par-based proteins may involve changes in protein endocytosis regulated by the underlying actin network via changes in organization. This latter possibility is supported by a recent study in which the knockdown of 14-3-3 (also known as Par5) by RNAi in the Sertoli cell epithelium was found to accelerate the kinetics of endocytosis of JAM-A (Wong et al., 2009).

Fig.3. Schematic drawing illustrating the functional domains of the components of the three known polarity protein complexes: Par-, Crb- and Scribble-based complexes (A), and the interactions between polarity proteins and junction proteins or signaling molecules in Sertoli cells during spermatogenesis (B).

Interacting polarity proteins are connected by double-arrowheads in “black”. Polarity proteins interacting with integral membrane proteins or other signaling molecules are indicated by gray arrowhead. The connecting line ended with a short bar represents inhibitory effect between proteins. Abbreviations used: PB1, Phox and Bem1p domain; semi-CRIB, semi-Cdc42/Rac interactive binding motif; PDZ, PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1 conserved domain; C1, protein kinase C conserved region 1; L27, Lin2 and Lin7 binding domain; SH3, Src homology 3 domain; GUK, guanylate kinase homologs conserved domain; LRR, leucine-rich repeats; LAPSD, LAP specific domain; WD, WD-40 repeats. [Colored version of this figure can be found in the on-line version of this issue of the journal]

3.1.2. GTPases

Cdc42 (cell division cycle 42), a small Rho GTPase known to work in concert with the Par-based polarity protein complex to regulate apico-basal polarity in mammalian epithelia (Iden and Collard, 2008; Joberty et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000; Yamada and Nelson, 2007). Cdc42 is also a component of the apical and basal ES in the rat testis (Lui et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2010) and it is also part of the Par6-based protein complex in the testis (Wong and Cheng, 2009; Wong et al., 2010). Cdc42 mediates its effects via protein trafficking in mammalian epithelial cells by targeting newly synthesized proteins as well as their recycling to the basolateral region of cells (Cohen et al., 2001; Kroschewski et al., 1999; Musch et al., 2001). Indeed, a recent report using dominant negative mutant of Cdc42 in Sertoli cells with an established TJ-barrier in vitro has shown that Cdc42 is a crucial regulator of endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking involving in the TGF-β3-induced acceleration of protein [e.g., coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) and ZO-1] endocytosis from cell surface to cell cytosol (Wong et al., 2010). In short, overexpression of dominant-negative Cdc42 in Sertoli cells was found to block the TGF-β3-mediated protein endocytosis that led to destabilizing the Sertoli cell TJ-permeability barrier, thereby blocking TGF-β3-induced TJ disruption (Wong et al., 2010). Overexpression of the Cdc42 dominant negative mutant also blocked the TGF-β3-induced re-distribution of CAR and ZO-1, retaining these proteins to the Sertoli cell-cell interface to strengthen the TJ-permeability barrier hereby blocking (Wong et al., 2010). Studies in other epithelia have shown that Cdc 42 is also an actin polymerization regulator that exerts its effects through three protein complex, i.e., WASPs/Arp2/3, formins/mDia (mammalian diaphanous), and LIMK/ROCK/cofilin (Heasman and Ridley, 2008; Jaffe and Hall, 2005; Lui et al., 2003a; Lui et al., 2003b; Ridley, 2006; Witte and Bradke, 2008). By altering the distribution of actin filaments and E-cadherin, Cdc42 was found to regulate cell tension and cell shape in MDCK and Caco-2 cells (Musch et al., 2001; Otani et al., 2006). Much work is needed to investigate the role of Cdc42 in actin organization in the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle.

3.1.3. 14-3-3s

14-3-3 is composed of a family of proteins, which are the mammalian homologs of Par5 in C.elegans (Morton et al., 2002), recently shown to be involved in cell adhesion and protein endocytosis at the BTB, resembling the function of Par6 (Sun et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2009). 14-3-3, a family of highly acidic proteins of about 30 kDa ubiquitously present in all mammalian tissues including the testis with different isoforms: 14-3-3α, β, θ, γ, δ, and ζ, and 14-3-3 was more abundant in germ cells versus Sertoli cells (Aitken, 2006; Chaudhary and Skinner, 2000; Morrison, 2009; Perego and Berruti, 1997; Sun et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2009). 14-3-3 proteins are capable of interacting with more than 200 proteins, which can exert their effects in various cellular processes, such as protein transcription, cell-cycle control and protein trafficking, and also act as scaffolding proteins to recruit target proteins to specific cellular domain to induce enzymatic activity or phorsphorylation (Jin et al., 2004; Pozuelo Rubio et al., 2004). In the Sertoli cell BTB in vitro, a knockdown of 14-3-3θ led to a mis-localization of N-cadherin and ZO-1, moving from the cell-cell interface into the cell cytosol, followed by a loss of cell adhesion function (Wong et al., 2009). These changes in protein localization were found to be the result of changes in protein endocytosis via an enhanced internalization of JAM-A and N-cadherin in the Sertoli cell epithelium (Wong et al., 2009). In adult rat testes, 14-3-3θ was found to be restrictively and spatiotemporally expressed at the BTB and the apical ES stage-specifically, with a significant decrease at the apical ES before spermiation at late stage VIII, indicating the involvement of 14-3-3θ in stabilizing the apical ES (Wong et al., 2009). Since earlier studies have suggested the involvement of 14-3-3s in integrin-based cell adhesion in other epithelia (Fagerholm et al., 2002; Han et al., 2001), and integrin is one of the major cell adhesion components at the apical ES (Mulholland et al., 2001; Siu and Cheng, 2004; Yan and Cheng, 2006), it remains to be determined whether 14-3-3 proteins regulate the breakdown and reassembly of the α6β1-integrin/laminin-α3β3γ3 complex at the apical ES during spermiogenesis. Additionally, 14-3-3s can also exert their effects on actin filament organization by binding to phosphorylated cofilin, which inactivates actin severing and depolymerization in BHK-21 cells (Gohla and Bokoch, 2002). In adjudin-treated rat testis, a loss of 14-3-3θ expression was detected in the seminiferous epithelium before actin network disruption and premature release of spermatid were detected (Wong et al., 2009). These findings implicate the possible role of 14-3-3θ, though the mechanism(s) still needs further investigations, in actin filament organization during spermatid detachment from the Sertoli cell in the seminiferous epithelium during the epithelial cycle.

3.2 The Crumbs (Crb) complex

The mammalian Crb3/Pals1 (Protein Associated with Lin Seven 1)/Patj (Pals1-Associated Tight Junction protein) complex was identified as the homolog of the Crb/Stardust/DmPATJ complex in Drosophila (Lemmers et al., 2002; Makarova et al., 2003). Of the three mammalian Crb isoforms of Crb1–3, Crb3 is the one that displays a predominant expression in epithelial cells including Sertoli cells in rat testes, possessing a small extracellular domain and a conserved cytoplasmic domain for interactions with Pals1 and Patj (Makarova et al., 2003; Roh et al., 2002b) (Figure 3). Pals1 is a membrane associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) protein that interacts with Lin-7, which is involved in endosomal sorting by inducing endocytosed proteins to basolateral membrane instead of lysosomes for degradation (Kamberov et al., 2000; Straight et al., 2001). Patj is another member of the Crb complex which physically interacts with Pals1, ZO-3, and claudin-1 via its PDZ domains (Lemmers et al., 2002; Roh et al., 2002a; Roh et al., 2002b). The Crb-based protein complex has been found to regulate TJ formation and confers cell polarity. For instance, overexpression of Crb3 or a disassociation between Crb3 and Pals1 was shown to delay TJ formation, destroying the apical-basal polarity in mammalian epithelial cells (Roh and Margolis, 2003; Roh et al., 2003; Shin et al., 2006). In MDCK cells, a knockdown of Patj expression by RNAi also led to a delay in TJ formation and redistribution of occludin (Michel et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2005). In addition to TJ formation, studies also detected the role of CRB complex in AJ dynamics by regulating E-cadherin trafficking (Wang et al., 2007). The three components of the Crb-based complex have all been found in the rat testis, and surprisingly with their predominantly expression in germ cells versus Sertoli cells (Wong et al., 2008b). Interestingly, Pals1 was found to structurally associate with JAM-C, the integral membrane protein at the apical ES in rodents and humans that confers cell adhesion, illustrating its function in conferring spermatid polarity during spermiogenesis (Wong et al., 2008b). Thus, crosstalks between the Crb- and Par-based polarity protein complexes are important in the adhesion of spermatids to Sertoli cells before spermiation (Wong et al., 2008b). In short, it is of interest to note that both the Par- and Crb-based protein complexes are localized both at the basal and the apical ES in the seminiferous epithelium instead of being restricted to the apical region of an epithelium in other mammalian tissues.

3.3. The Scribble/discs large (Dlg)/lethal giant larvae complex (Lgl) complex

3.3.1. Scribble

The Scribble protein complex composed of three tumor suppressors, namely Scribble, discs large (Dlg), and lethal giant larvae (Lgl), which are restricted to the baso-lateral region in a cell epithelium near the basal lamina, displaying mutually exclusive distribution versus the Par- and the Crb-based polarity complexes that restricted to the apical region at the location of the TJ (Assemat et al., 2008; Iden and Collard, 2008; Wong and Cheng, 2009). In the rat testis, both the Par- and the Crb-based component proteins are found at the apical and basal ES (Wong et al., 2008b; Wong et al., 2009), however, Scribble is mostly restricted to the basal ES at the BTB (Su et al., 2012c) (Figure 3). But all these proteins display highly restrictive spatiotemporal expression at the corresponding site in the epithelium during the epithelial cycle, illustrating the mutually exclusive distribution pattern of these three protein complexes is less distinctive in the seminiferous epithelium. Scribble was initially identified in Drosophila as a LAP [LRR (leucine-rich repeats) and PDZ (PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1) domain] protein containing 16 LRRs, 1 LAPSD (LAP specific domain, located between LRR and PDZ domain) and 4 PDZ domains (Bilder and Perrimon, 2000; Nakagawa and Huibregtse, 2000) (Figure 3). The LRR and the LAPSD domains are responsible for anchoring members of this protein family to the membrane while the PDZ domains are found to be involved in epithelial polarization and cell proliferation regulation (Legouis et al., 2003; Zeitler et al., 2004). Although the biological roles of mammalian Scribble (hScrib) are largely unknown, hScrib silencing in MCF10A cells led to defects in wound closure, failing to polarize and to recruit Cdc42 and Rac1 to the leading edge, which is crucial for cell polarization and migration (Dow et al., 2007). A study in mammary epithelial cells also revealed a disrupted 3D acinar morphogenesis after hScrib depletion via an inhibition on the establishment of apico-basal polarity (Zhan et al., 2008). Besides cell polarity regulation, hScrib is also involved in epithelial cell adhesion. For example, hScrib was found to directly interact with ZO-2, a TJ adaptor protein (Chlenski et al., 2000; Glaunsinger et al., 2001), in COS-7 cells via the PDZ domain of hScrib and the carboxyl-terminus of ZO-2 (Metais et al., 2005). Interestingly, a disruption of cell adhesion in MDCK cells by hScrib knockdown could be partially rescued by overexpressing E-cadherin-α-catenin fusion protein but not E-cadherin alone (Qin et al., 2005). This indicates that Scribble stabilizes epithelial cell adhesion by enhancing or stabilizing the coupling between E-cadherins and catenins.

3.3.2. Lgl

Lgl gene encodes a 130-kDa protein that contains stretches of sequences that are similar to several cell adhesion proteins (Lutzelschwab et al., 1987). Mammalian Lgl proteins (Lgl 1–4) contain at least 4–5 putative WD-40 repeat motifs (Klezovitch et al., 2004), which often function as coordinators of macromolecular protein complexes, such as for protein-protein interaction, receptor-ligand interaction in signal transduction, pre-mRNA processing, cell cycle regulation, and cytoskeleton assembly (Baek, 2004; Dubrovskaya et al., 1996; Klezovitch et al., 2004; Li and Roberts, 2001; Ohtoshi et al., 2000) (Figure 3). Resembling its homolog in Drosophila (Betschinger et al., 2003; Betschinger et al., 2005), mammalian Lgl in MDCK cells was found to compete with Par3 for interaction with aPKC-Par6 (Yamanaka et al., 2003). Further study revealed that the suppression of interaction between aPKC-Par6 and Par3 (or Cdc42) by mLgl led to the suppression of aPKC-Par6-Par3 activity (Yamanaka et al., 2006). More importantly, Lgl was dissociated with Par6 after the phosphorylation of Lgl within a highly conserved region by aPKC, which determined restrictive localization of mammalian Lgl to the lateral domain and was crucial for epithelial polarization (Musch et al., 2002). These reports thus confirmed the role of mutual inhibition between Lgl and aPKC-Par6 in regulating mammalian epithelial cell polarity.

3.3.3. Dlg

Dlg was also identified as a member of the MAGUK family that often distributes at cell junctions and contains distinct peptide domains such as PDZ1–3, SH3, HOOK, and GUK (Hough et al., 1997; Woods and Bryant, 1991) (Figure 3). In mammals, hDlg1 was found to co-localize with E-cadherin at cell-cell interface in renal and intestinal epithelial cells (Laprise et al., 2004). RNAi knockdown of hDlg was shown to alter AJ integrity and deterred PI3K/p85 recruitment to cell-cell contact site, which is known to participate in AJ assembly and the association of AJ components with the cytoskeleton (Laprise et al., 2004; Laprise et al., 2002). These findings demonstrate that hDlg is a key regulator of junction assembly in mammalian epithelia, even though the underlying mechanism(s) requires further investigations.

3.3.4. The Scribble-based protein complex regulates actin dynamics in the testis

Scribble, Lgl2 and Dlg1 are recently shown to be expressed by Sertoli and germ cells in the rat testis (Su et al., 2012c). While immunoreactive Scribble was also detected at the apical ES, Scribble was predominantly restricted to the BTB, co-localized with occludin and ZO-1 (Su et al., 2012c), analogous to the finding in the intestinal monolayers (Ivanov et al., 2010), displaying a stage-specific expression pattern with highest expression at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle (Su et al., 2012c). This reciprocal relationship between the expression of Scribble and BTB restructuring indicated the likely involvement of the Scribble complex in BTB dynamics. In fact, while the silencing of Scribble or Dlg1 by RNAi failed to affect the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function, the simultaneous knockdown of Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 or the single knockdown of Lgl2 in cultured Sertoli cells was found to promote the TJ-permeability barrier function, confirming the notion that the Scribble complex is involved in BTB dynamics and that Lgl2 appears to be a more dominating regulatory member (Su et al., 2012c). This promoting effect on the BTB function following the knockdown of Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 in Sertoli cells in vitro was confirmed in vivo when all three genes were knocked down, which led to an increase in occludin localization and distribution at the BTB (Su et al., 2012c). Also consistent with the in vitro findings, a single knockdown of Lgl2, but not Scribble alone, was found to promote the localization of occludin at the BTB (Su et al., 2012c). This effect, however, is highly stage-specific in vivo, since it only affects stage VIII tubules (Su et al., 2012c). Furthermore, all three proteins, namely Scribble/Dlg1/Lgl2 are required to maintain the polarity of spermatids in stage VII-VIII tubules since only triple silencing of Scribble/Lg12/Dlg1, but not either protein alone, was found to alter the spermatid polarity in vivo (Su et al., 2012c). These findings thus support the role of the Scribble/Lgl2/Dlg1 complex in regulating spermatid polarity, consistent with earlier reports regarding the role of this complex in maintaining mammalian cell polarity (Musch et al., 2002; Yamanaka et al., 2006). The striking observation in this study is that many of the effects summarized herein following the knockdown of different components of the Scribble complex appears to be mediated by changes in F-actin organization in the Sertoli cell in vitro and in vivo, which modulates protein recruitment at either the apical or the basal ES that led to changes in protein localization or distribution at these sites, which in turn modulate cell adhesion at the Sertoli-Sertoli or Sertoli-spermatid interface. For instance, a simultaneous knockdown of Scribble, Lgl2, and Dlg1, by RNAi in primary Sertoli cells cultured in vitro that led to an increase in localization of β-catenin and occludin to the Sertoli cell-cell interface which contributed to a “tightening” of the TJ-permeability barrier was associated with a re-organization of actin filaments, in which F-actin was found to be concentrated to cell cortex close to the plasma membrane instead of evenly distributed in cell cytosol (Su et al., 2012c). This thus strengthens the Sertoli cell TJ function. The in vivo data also confirm the role of the Scribble complex in strengthening the TJ barrier following the simultaneous knockdown of Scribble/Lgl2/Dlg1 in the testis by re-organization of the F-actin network in the epithelium in which F-actin was found to be increased at the BTB while weakened and reduced at the apical ES in stage VIII tubules (Su et al., 2012c). In short, such an increase in F-actin at the BTB promotes the recruitment of occludin to the BTB, but the reduced F-actin at the apical ES also led to considerable loss of laminin-γ3 chain, an apical ES and elongating/elongated spermatid-associated cell adhesion protein (Yan and Cheng, 2006), thereby inducing a loss of spermatid polarity in these stage VIII tubules (Su et al., 2012c). These recent data thus demonstrate that the Scribble/Dlg/Lgl complex is involved in conferring cell polarity in the seminiferous epithelium epithelium, but it also plays a crucial role in cell adhesion via its effects on protein recruitment and/or localization, and it appears that these effects are mediated, at least in part, by changes in F-actin organization in the Sertoli cell during the epithelial cycle.

4. Cytokines, steroids, mTOR signaling complexes and non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases on actin dynamics in the seminiferous epithelium

At stage VIII of the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis, restructuring of the BTB involves the assembly of “new” TJ-fibrils below preleptotene spermatocytes connected in clones that are crossing the BTB before the disassembly of the “old” TJ-fibrils above these transiting cells, thus the integrity of the immunological barrier is maintained during BTB restructuring. In other stages of the epithelial cycle, the apical ES also undergoes extensive restructuring due to reshaping and relocation of developing spermatids, such as moving towards the tubule lumen at stage XIV-III, downwards to the basement membrane at stage IV-V, to be followed by moving upwards to the luminal edge during stage VI-VIII. Since both the basal ES at the BTB and the apical ES are actin filament-rich cell adhesion ultrastructures, it is conceivable that there are rapid changes in F-actin organization to maintain the polarity of Sertoli cells and spermatids during the epithelial cycle. Herein we summarize and critically evaluate findings in the past decade on the regulation of F-actin network in the epithelium by cytokines and other signaling complexes.

4.1. TGF-βs, TNFα, and testosterone modulate protein endocytosis and actin dynamics

Cytokines, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β3 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α (Li et al., 2006; Lui et al., 2001; Xia et al., 2006), and steroids (e.g., testosterone) (Chung and Cheng, 2001; Janecki et al., 1992; Meng et al., 2005; Siu et al., 2009a; Wang et al., 2006) were reported to regulate junction restructuring at the Sertoli cell BTB in vitro and in vivo, consistent with earlier reports regarding their roles in other epithelia, such as small intestine and kidney (Al-Sadi et al., 2009; Walsh et al., 2000). The disruptive and the promoting effects of cytokines and testosterone on BTB integrity, respectively, were subsequently shown to be mediated by changes in endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking in which both cytokines (e.g., TGF-β2) and testosterone were found to accelerate protein endocytosis at the Sertoli cell BTB (Yan et al., 2008). However, cytokines facilitate and target endocytosed proteins to late endosomes for their eventual degradation whereas testosterone promotes recycling of the endocytosed proteins back to the Sertoli cell surface (Yan et al., 2008). These androgen-induced junction restructuring changes apparently were not mediated via the classical androgen receptor pathway, instead, it appears to involve an activation of c-Src and MAPK downstream (Cheng et al., 2007; Walker, 2010; Walker, 2011). These effects may also involve changes in F-actin re-organization at the Sertoli cell BTB, which in turn, facilitates endocytic vesicle-mediated trafficking. Indeed, cytokines (e.g., TNFα) and testosterone were found to affect F-actin organization in cultured Sertoli cells with an established TJ-permeability barrier in vitro (Su et al., 2012b). For example, in Sertoli cells treated with TNFα, but not TGF-β3, F-actin displayed a remarkably re-organization versus control cells in which actin filaments were considerably concentrated around cell nuclei instead of a uniform distribution in control cells; however, in cells treated with testosterone, F-actin and also filamin A localized more predominantly at the cell cortex near the plasma membrane, apparently being used to strength the intensity of Sertoli cell TJ-barrier (Su et al., 2012b). Indeed, Sertoli cells treated with testosterone display a tighter TJ-barrier (Xiao et al., 2011) and testosterone could also protect the Sertoli cell TJ-barrier from cadmium-induced TJ disruption (Siu et al., 2009a). It is of interest to note that the TNFα- or testosterone-induced F-actin re-distribution in Sertoli cells may be mediated, at least in part, via filamin A since filamin A also displayed similar changes in its re-organization following these treatments versus controls (Su et al., 2012b). Other studies have shown that filamin A is a non-muscle actin filament cross-linker (Su et al., 2012a) known to be involved in recruiting TJ-, basal ES-, and GJ-proteins to the BTB for its assembly during post-natal development (Su et al., 2012b).

The effects on protein endocytosis and actin dynamics mediated by cytokines and testosterone likely involve the MAPK signaling cascade. In the testis, MAPK is involved in virtually all steps of spermatogenesis, such as mitotic renewal of spermatogonia and stem cells, meiosis, spermiogenesis, and spermiation (Li et al., 2009a; Lie et al., 2009b). Furthermore, p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 were identified as two putative signaling pathways utilized by TGF-β3 to regulate BTB dynamics and junction restructuring in the seminiferous epithelium (Li et al., 2006; Lui et al., 2003c; Wong et al., 2004; Xia and Cheng, 2005). The ERK pathway was also reported to be activated by androgen receptor via Src in Sertoli cells in the nongenomic pathway (Cheng et al., 2007). In addition, studies using the adjudin model have revealed that the adjudin-induced anchoring junction restructuring is mediated via an activation of cytokines and ERK signaling pathway (Siu et al., 2003a; Siu et al., 2005; Xia and Cheng, 2005). Furthermore, ERK was also shown to take part in spermatids adhesion since the use of a specific MEK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, was found to delay the adjudin-induced spermatid loss from the seminiferous epithelium (Xia and Cheng, 2005), and adjudin was also shown to mediate its effects via changes in F-actin organization at the Sertoli cell BTB (Mruk and Cheng, 2004a). Additionally, the knockdown of either Lgl2 alone (but not Scribble or Dlg1 alone) or a triple knockdown of Scribble, Dlg1 and Lgl2 that induced F-actin organization in the seminiferous epithelium by strengthening F-actin at the basal ES and thereby promoting Sertoli cell TJ-barrier function, but reducing F-actin at the apical ES and thus perturbing spermatid polarity, was found to associate with an up-regulation of pERK1/2 (Su et al., 2012c). This finding is consistent with earlier reports in which Scribble, a tumor suppressor, was shown to reduce mammalian cancer cell invasion and mitotic proliferation by promoting ERK phosphorylation and its nuclear translocation (Dow et al., 2008; Nagasaka et al., 2010). Collectively, these findings suggest that the Scribble protein complex knockdown-induced pERK1/2 upregulation may be associated, directly or indirectly, with endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking, such as via changes in protein localization via protein endocytosis, transcytosis and recycling, which requires further investigations.

4.2. Interleukin-1α and actin dynamics

Interleukin-1α (IL-1α), a pro-inflammatory cytokine known to induce actin stress fiber formation in different cell types (Singh et al., 1999), was found to facilitate BTB restructuring and induced mis-orientation of elongated spermatocytes in stage VII-VIII tubules (Sarkar et al., 2008). The effectors of IL-1α signaling are members of the Rho GTPase family, such as RhoA, Rac and Cdc42, which are known regulators of actin cytoskeleton, cell polarity and vesicular transport (Heasman and Ridley, 2008; Ridley, 2006). Previous studies have demonstrated a high level of expression of IL-1α throughout the seminiferous epithelial cycle except for a considerable decline at stage VII, which was followed by a distinctive up-regulation at stage VIII (Gerard et al., 1992; Li et al., 2009b; Syed et al., 1995; Wahab-Wahlgren et al., 2000). This suggests that an up-regulation of IL-1α expression may facilitate BTB restructuring as well as spermatid release at spermiation at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle. This postulate is supported by earlier findings which illustrated local administration of recombinant IL-1α to the testis was found to perturb the BTB integrity and Sertoli-germ cell adhesion, causing a “leaky” barrier which was coupled with unwanted spermatid release mimicking “spermiation” (Sarkar et al., 2008). A recent study using polarized Sertoli cells cultured in vitro with an established functional TJ-permeability barrier has shown that the IL-1α-induced BTB remodeling is mediated via changes in F-actin re-organization associated with its effects on actin binding proteins (Lie et al., 2011). For instance, treatment of the Sertoli cell epithelium with IL-1α was found to cause mis-localization of Eps8, an actin barded end capping and bundling protein, in this in vitro system, resulting in an uncontrolled capping of the actin filaments, causing an overgrowth of actin filaments and the loss of bundle-like appearance, resembling those phenotypes after Eps8 knockdown by RNAi (Lie et al., 2011; Lie et al., 2009a). Similarly, an increased in Arp3 protein level, which is part of the Arp2/3-N-WASP protein complex that induces branched actin polymerization, was detected in the Sertoli cell epithelium after IL-1α treatment (Lie et al., 2011). This thus caused the loss of properly organized actin filament bundles but a branched actin network across the Sertoli cell (Lie et al., 2011). Collectively, these findings have demonstrated that IL-1α regulates BTB function via its effects on actin dynamics even though its effectors require further investigation.

4.3. mTORC1 complex affects actin dynamics and protein recruitment in the testis

Ribosomal protein S6 (rpS6), the downstream signaling molecule of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway, which is known for its role in cell growth and proliferation by regulating protein synthesis (Conn and Qian, 2011; Magnuson et al., 2012; Mok et al., 2013a; Zhou and Huang, 2010), was recently shown to be involved in F-actin organization and protein recruitment at the Sertoli cell BTB both in vitro and in vivo (Mok et al., 2012b). The activated form of rpS6, p-rpS6, was found to be up-regulated at the BTB in stage VIII-IX tubules at the time of BTB restructuring (Mok et al., 2012b), implicating its involvement in BTB dynamics. Indeed, its knockdown by shRNA was found to promote the Sertoli cell TJ barrier function via an increase in recruitment of adhesion proteins, such as occludin and claudin-11 to the BTB, and an extensive re-alignment of F-actin bundles at the cell-cell interface, which in turn contributed to a tightening of the BTB (Mok et al., 2012b). More important, these findings in vitro were reproduced in vivo by transfecting rat testes with rpS6 shRNA (Mok et al., 2012b). Furthermore, these findings in the testis is also in agreement with recent studies in other epithelia which have illustrated the involvement of mTORC1 pathway in barrier function regulation and F-actin organization, such as the TJ barrier in kidney glomerulus and in mouse bladder except that the effector molecule(s) in these other studies was unknown (Aronova et al., 2007; Inoki et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2008; Shorning et al., 2011). It is likely that rpS6 mediates its effects via changes in the kinetics of protein internalization, recycling, or degradation, since TOC1 was found to functionally associated with endocytosis related genes and rapamycin-induced TOC1 inhibition was accompanied with actin polarization disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Aronova et al., 2007). In short, the rpS6-mediated effects in actin organization may contribute to changes in endocytic vesicle-mediated protein trafficking. In the rat testis, a direct interaction between rpS6 and other two actin-binding proteins, namely Arp3 and Eps8, was not detected (Mok et al., 2012b), except that the knockdown of rpS6 in Sertoli cell cultures was associated with a mild but persistent decline in the Eps8 level (Mok et al., 2012b). In short, these results illustrate that mTORC1 pathway is crucial to maintain BTB integrity during spermatogenesis by mediating protein recruitment and protein localization via changes in F-actin organization in the Sertoli cell.

4.4. Non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases regulate actin dynamics via activation of actin binding/regulatory proteins

Recent studies have shown that non-receptor protein tyrosine kinases, such as c-Yes (a member of the nonreceptor Src protein kinase family) and FAK, are involved in regulating actin organization in the Sertoli cell epithelium at the BTB (Xiao et al., 2011) (Lie et al., 2012) via a unique mechanism. In a study using an inhibitor, SU6656, that blocked c-Yes catalytic activity selectively in the Sertoli cell epithelium, F-actin was found to be re-organized, in which actin filaments were considerably diminished at the Sertoli cell cortical region but retrieved and more concentrated at the cell cytosol, failed to support the TJ, thereby inducing re-distribution of occludin and N-cadherin, moving away from the cell surface and into the cell cytosol (Xiao et al., 2011). The net results of these changes led to a disruption of the Sertoli cell TJ barrier function (Xiao et al., 2011). Yet the molecular mechanism(s) underlying these changes was not known. Another line of studies that examines the role of FAK in the testis has shed new lights into a novel mechanism on how protein kinases regulate actin dynamics. FAK, as its name implies, exerts its effects at the focal adhesion complex (or focal contact), an actin-based cell-matrix anchoring junction type in epithelia at the cell-matrix interface; which together with c-Src, they are two important mediators of integrin-based signaling functions (Boutros et al., 2008; Cheng and Mruk, 2009; Hall et al., 2011; Mitra and Schlaepfer, 2006; Wong and Cheng, 2011; Xiao et al., 2012). However, FAK is found at the Sertoli cell-cell interface at the BTB instead of at the Sertoli-basement membrane interface (Siu et al., 2009b; Siu et al., 2003b). More important, p-FAK-Tyr397 is restricted exclusively to the apical ES and highly expressed in stage VII-early VIII tubules and virtually diminished by late stage VIII when spermiation takes place (Beardsley et al., 2006; Siu et al., 2003b); whereas p-FAK-Tyr407 is found at both the BTB and the apical ES but displayed a highly restrictive spatiotemporal expression during the epithelial cycle (Lie et al., 2012). Using different phosphomimetic (e.g., FAK Y397E, FAK Y407E, or FAK Y397E & Y407 E double mutant) and non-phosphorylatable (e.g., FAK Y397F, FAK Y407F) mutants of FAK, it was found that p-FAK-Tyr397 and -Tyr407 displayed antagonistic effects on the Sertoli cell BTB function with the former perturbs and the latter promotes TJ-permeability barrier, respectively (Lie et al., 2012). Interestingly, these effects are mediated via the Arp2/3-N-WASP protein complex that induces branched actin polymerization, thereby affecting actin dynamics (Lie et al., 2012). In short, overexpression of FAK Y407E that “tightens” the TJ-permeability barrier was shown to be mediated by an increase in association between Arp3 and N-WASP, thereby promoting F-actin re-organization in the Sertoli cell epithelium with more actin filaments localized to the Sertoli cell-cell interface, thereby strengthening the basal ES at the BTB (Lie et al., 2012). These findings thus suggest that p-FAK-Tyr407 that promotes the Sertoli TJ function is likely mediated by an increase in phosphorylation of N-WASP, which induces the formation of the activated Arp2/3-N-WASP complex to activate branched actin polymerization, altering the F-actin organization in Sertoli cells that leads to an increase in actin filaments at the basal ES of the BTB. Much work is needed to confirm these observations in vivo to assess if p-FAK-Tyr397 and -Tyr407 serve as molecular “switches” to turn “on” and “off” of adhesion function at the apical and basal ES during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis via their effects on the F-actin at these sites.

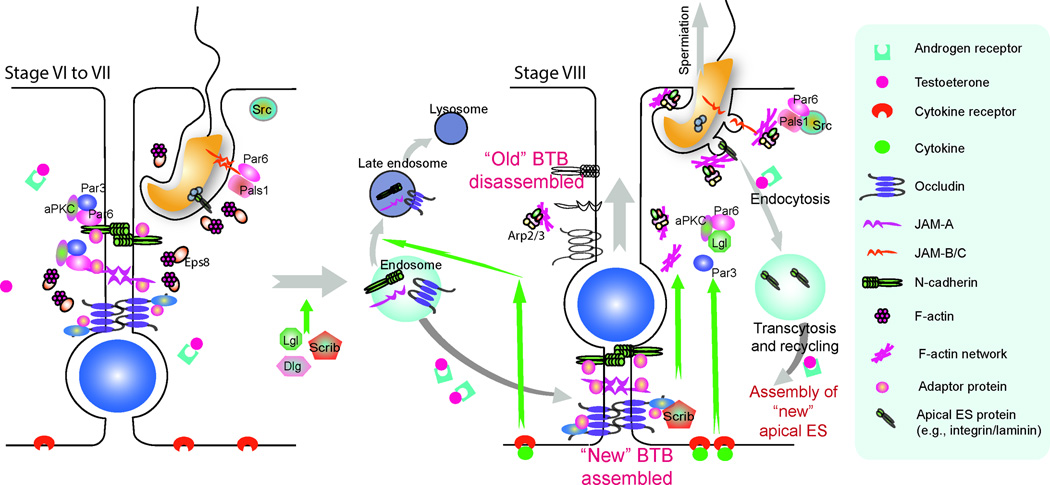

5. An integrated model on the regulation of actin dynamics in the seminiferous epithelium

Based on the latest findings in the field as summarized in the above sections, it is increasingly clear that intact actin filament bundles that are abundantly found: (i) at the apical ES that confer cell adhesion at the Sertoli-spermatid (step 8–19 spermatids) interface and (ii) at the the basal ES that confer cell adhesion at the BTB between Sertoli cells, are maintained by a combination of actin-binding proteins (e.g., drebrin E), actin regulatory proteins (e.g., Arp2/3 complex, Eps8), polarity proteins (e.g., Par6, 14-3-3, Scribble, Dlg, Lgl) and nonreceptor protein kinase (e.g., c-Src) under the influence of testosterone and cytokines (e.g., TNFα, TGF-ß3) (Figure 4). For instance, the Par-based proteins form a stable complex with JAM-B/C to confer apical ES adhesion (Wong et al., 2008b), and the actin filament bundles are stabilized by the presence of Eps8 (Lie et al., 2009a) at stage VI-VII of the epithelial cycle under the influence, at least in part, of testosterone (Figure 4). However, at stage VIII of the epithelial cycle, actin filament bundles become “de-bundled”, replaced by the “branched” actin network that destabilizes the apical ES and basal ES, facilitating protein endocytosis, which are mediated via the combined action of: (i) Arp2/3 complex activation that favors branched actin polymerization (Lie et al., 2010b), (ii) association of the Par6/Pals1 with c-Src in which Par6/Pals1 no longer tight associated with JAM-B/C (Wong et al., 2008b), and (iii) an increased expression of Scribble/Dlg/Lgl at the ES (Su et al., 2012c). These changes are also regulated, at least in part, by an increase in the levels of cytokines (e.g., TGF-ß3 and TNFα) in the microenvironment (Cheng and Mruk, 2010), as well as by changes in the spatiotemporal expression of p-FAK-Tyr407 and -Tyr397 at the apical ES and basal ES (Lie et al., 2012). The sum of these changes leads to a disruption of the apical ES and basal ES to facilitate spermiation and BTB restructuring, respectively. Furthermore, changes in the actin configuration from its “bundled” to “de-bundled” and “branched” state also facilitate endocytic-vesicle mediated protein trafficking events that either lead to endosome-mediated protein degradation or transcytosis and recycling, so that proteins from the “old” apical ES or “old” basal ES can be “recycled” to assemble “new” apical or basal ES, providing an efficient mechanism to facilitate continuous cycles of spermatogenesis (Figure 4).

Fig.4. A hypothetical model illustrating BTB and apical ES restructuring during the epithelial cycle is mediated via cooperation of F-actin reorganization and endosome-mediated protein trafficking involving polarity proteins and actin regulatory/binding proteins, under the influence of testosterone and cytokines.