Abstract

Present within bacteria, plants, and some lower eukaryotes 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (DAHPS) catalyzes the first committed step in the synthesis of a number of metabolites, including the three aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan. Catalyzing the first reaction in an important biosynthetic pathway, DAHPS is situated at a critical regulatory checkpoint—at which pathway input can be efficiently modulated to respond to changes in the concentration of pathway outputs. Based on a phylogenetic classification scheme, DAHPSs have been divided into three major subtypes (Iα, Iβ, and II). These subtypes are subjected to an unusually diverse pattern of allosteric regulation, which can be used to further subdivide the enzymes. Crystal structures of most of the regulatory subclasses have been determined. When viewed collectively, these structures illustrate how distinct mechanisms of allostery are applied to a common catalytic scaffold. Here, we review structural revelations regarding DAHPS regulation and make the case that the functional difference between the three major DAHPS subtypes relates to basic distinctions in quaternary structure and mechanism of allostery.

Keywords: allostery, chorismate mutase, 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase, feedback regulation, inhibition, phenylalanine, shikimate pathway, tryptophan, tyrosine

Introduction

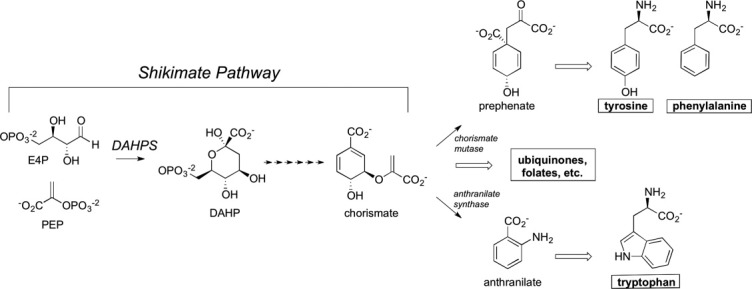

Present in bacteria, plants, and some eukaryotes, the shikimate pathway consists of seven enzymes that convert phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and erythrose 4-phosphate (E4P) to chorismate.1,2 Chorismate is situated at a biosynthetic branch point from which the paths that lead to phenylalanine/tyrosine and tryptophan (as well as a number of other aromatic metabolites) first diverge (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Abridged aromatic metabolite biosynthetic tree. Emphasis is placed on the DAHPS catalyzed reaction, the chorismate branch point, and the metabolite end products. Chorismate mutase and anthranilate synthase catalyze the first committed steps in the respective phenylalanine/tyrosine and tryptoplan shunts.

3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase (DAHPS) catalyzes the conversion of PEP and E4P to 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate, the first reaction in the shikimate pathway (Fig. 1). As the pathway's first enzyme, DAHPS is situated at a pivotal gateway where changes in the cellular concentration of pathway outputs can efficiently feedback to affect pathway input. Evolutionary processes have devised and maintained an array of mechanisms for rendering DAHPS responsive to downstream reaction products. A number of studies have revealed complex networks of transcriptional and allosteric controls that interact to maintain DAHPS activity.3–5 Although organismal variability in DAHPS transcriptional control is interesting in its own right, the diversity of mechanisms of DAHPS allostery is truly exceptional—perhaps the most characterized for any enzyme.1 This evolutionary quirk has established DAHPS as an intriguing evolutionary case study, allowing distinct mechanisms of allosteric inhibition to be studied in relation to a common catalytic scaffold and making the enzyme an exemplary model system for the study of allostery.

A widely employed classification system divides DAHPSs into two classes (type I and II) based upon phylogenetic reconstructions. Relying upon finer sequence distinctions, the type I class has been parsed into subtypes (Iα and Iβ).6–10 These subtypes can be further divided based upon features of allostery. Subtle sequence differences determine whether type Iα enzymes are inhibited by phenylalanine, tyrosine, or tryptophan, whereas the presence or absence of distinct N- or C-terminal extensions are associated with unregulated, phenylalanine/tyrosine regulated, and chorismate/prephenate regulated type Iβ enzymes.

Since the first crystal structure was reported in 1999, more than 30 DAHPS structures—encompassing Iα, Iβ, and II types and most of the known regulatory subclasses—have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB). When viewed collectively, the enzymes that make up the DAHPS family exhibit surprising structural diversity but also unexpected similarities. Here, we review recent structural findings (see Table I for summary of covered structures) and discuss what they reveal about the mechanism and evolution of DAHPS allostery.

Table I.

DAHPS Structures Discussed in Manuscript

| Organism | Quaternary state | Relevant PDB codes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype Iβ | |||

| Unregulated | P. furiosus | Dimer or tetramer | 1ZCO11 |

| A. pernix | Dimer or tetramer | 1VS112 | |

| Tyrosine/Phenylalanine | T. maritima | Tetramer | 1RZM,133PG914 |

| Chorismate/Prephenate | L. monocytogenes | Tetramer | 3NVT15 |

| Subtype Iα | |||

| Phenylalanine | E. coli | Tetramer | 1QR7,161KFL17 |

| Tyrosine | S. cerevisiae | Dimer | 1OFP,181OF6,191OG020 |

| Tryptophan | – | – | – |

| Type II | |||

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine + Tryptophan | M. tuberculosis | Tetramer | 2B7O,212W19,223KGF23 |

Unregulated Type Iβ DAHPSs

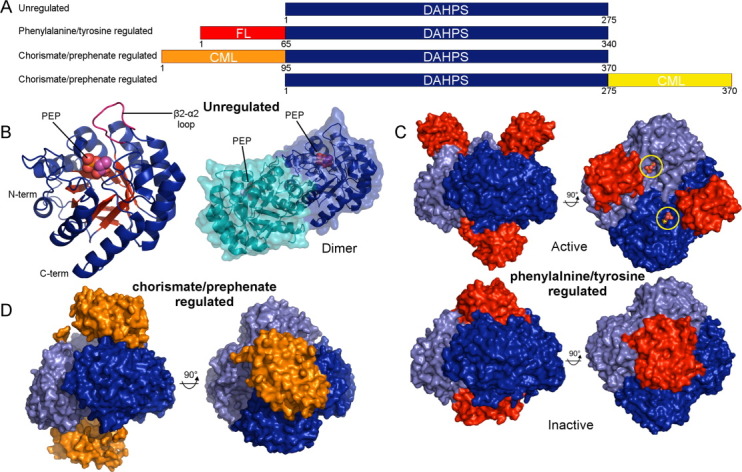

The structural architecture of DAHPS is best illustrated by the unregulated type Iβ subtype [Fig. 2(a)], [the Iα/Iβ designation is somewhat unfortunate as the Iβ enzymes appear to be the more primitive subtype]. Structures of these ∼275 amino acid enzymes from Aeropyrum pernix and Pyrococcus furiosus reveal a catalytic core unencumbered by allosteric appendages.11,12,24,25 An analysis of the structure reveals that the catalytic apparatus adopts a classic TIM barrel (α/β)8 fold with an extended 2β-2α connecting loop that caps the barrel top and defines a wall of the active site [Fig. 2(b)]. Both of the unregulated Iβ DAHPSs that have been structurally studied are dimeric in solution conditions but in crystals exhibit tetrameric arrangements, similar to subsequently discussed regulated Iβ enzymes.11,12,24,25 Although the physiological oligomeric state remains uncertain, since the dimeric form retains catalytic proficiency and is useful for subsequent comparisons, our analysis of the enzyme will focus on the homodimeric state [Fig. 2(b)].

Figure 2.

Overview of type Iβ DAHPS structure and allostery. (A) Schematic representation of domain construction in type Iβ regulatory subclasses with approximate chain lengths noted. Chorismate mutase-like (CML) and ferredoxin-like (FL) regulatory domains are labeled. (B) The tertiary and quaternary structures of the P. furiosus type Iβ unregulated DAHPS (PDB code 1ZCO) are depicted in cartoon representation with bound PEP molecules depicted as spheres. (C) Top panel: structure of the T. maritima phenylalanine/tyrosine regulated type Iβ DAHPS in complex with E4P (yellow circles) + PEP (PDB code 1RZM). Bottom panel: in the inhibited state the regulatory domains dimerize and tyrosine molecules (not visible in this representation) bind at the domain-domain interface (PDB code 3PG9). (D) The L. monocytogenes N-terminal chorismate/prephenate regulated type Iβ DAHPS structure (PDB code 3NVT). In (C) and (D) the two catalytic dimers that form the tetramer are colored different shades of blue and the regulatory domains are colored red and orange. An interactive view is available in the electronic version of the article

A comparison of structures of unregulated type Iβ DAHPS and 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate synthase (KDO8PS) underscores the close relationship of these enzymes. Using PEP and arabinose 5-phosphate as substrates, KDO8PS employs a related mechanism to catalyze a similar reaction to DAHPS. Phylogenetic analyses had previously demonstrated that type Iβ DAHPS and KDO8PS share a common ancestry.7–10 However, even considering these mechanistic and phylogenetic similarities, the degree of structural conservation between type Iβ DAHPS and KDO8PS is somewhat surprising. The two enzymes are exceedingly similar both in tertiary (RMSD = 1.2 Å over 165 Cα atoms, P. furiosus DAHPS to E. coli KDO8PS) and quaternary structure, with the type Iβ enzyme exhibiting a higher degree of structural conservation to KDO8PS than to related type Iα or II DAHPS subtypes.26,27

Phenylalanine/Tyrosine Regulated Type Iβ DAHPS

Relative to the unregulated variant, a subset of Iβ DAHPSs contain a characteristic ∼65 amino acid N-terminal extension [Fig. 2(a)]. Falling within this family, the Thermotoga maritima DAHPS is allosterically regulated by tyrosine (and to a significantly lesser extent by phenylalanine).28 Crystal structures of the T. maritima phenylalanine/tyrosine regulated enzyme reveal that the N-terminal extension establishes a discrete domain that adopts a fold described as ACT28 or ferredoxin-like (FL).13,26 The presence of the FL domain causes the dimer observed in the unregulated DAHPS structures to itself dimerize to produce the homotetrameric functional assembly.28 How the FL domain facilitates tetramer formation is unclear from the inhibitor-free structure, which reveals that the four FL domains splay away from the tetramer interface, leaving the active sites open and accessible [Fig. 2(c), top panel].26

A recently reported tyrosine complex clarifies the mechanism by which the FL domain promotes tetramer assembly.28 This structure reveals that inhibitor binding is associated with dramatic FL domain repositioning. In the inhibited state the two FL domains on either side of the catalytic tetramer have rotated toward the central axis of the tetramer, creating a pair of regulatory dimers that sandwich the catalytic tetramer [Fig. 2(c), bottom panel]. The inhibitor bound conformational state is stabilized by a pair of tyrosine molecules that bind and bridge the newly established regulatory domain-domain interface.14,28

The mechanism by which this unusual induced regulatory domain oligomerization inhibits activity remains somewhat ambiguous. It was recently shown that fusing the T. maritima FL domain to the P. furiosus unregulated catalytic core yields a chimeric protein responsive, but less so than the T. maritima DAHPS, to tyrosine and phenylalanine.29 This implies that the proper positioning of the regulatory domain is sufficient for inhibition but also suggests that specific interactions with the catalytic core present in the T. maritima but not chimeric protein are required for maximal inhibitory effect. In inhibitor bound structures of the T. maritima and chimeric protein, the FL dimer caps the TIM barrel and a narrow channel presents the only route to the active site. It is likely that this conformational state decreases activity to some extent by occluding substrate binding or product release. As the regulatory domains directly interact with the catalytic domain—specifically with the 2β-2α and 8β-8α connecting loops, both of which are directly involved in substrate/cofactor binding—inhibition is likely also mediated by a conventional induced conformational change mechanism.

Chorismate/Prephenate Regulated Type Iβ DAHPSs

Chorismate, the product of the shikimate pathway, is also positioned at an important biosynthetic branch point. The conversion of chorismate to prephenate by chorismate mutase directly leads to the biosynthesis of phenylalanine and tyrosine, while a handful of other chorismate utilizing enzymes direct flux towards the synthesis of other metabolites, including tryptophan (Fig. 1). Situated at such a critical biosynthetic node, chorismate/prephenate represent logical mid-pathway regulatory checkpoints.

It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that a subclass of Iβ enzymes have evolved allosteric responses to chorismate and/or prephenate.30–32 In most cases these enzymes contain a ∼95 amino acid N-terminal extension that has sequence homology to the chorismate mutase enzyme [Fig. 2(a)]. Fascinatingly, DAHPSs with a similar C-terminal extension that also respond to chorismate/prephenate have been described [Fig. 2(a)].32 The existence of two distinct domain constructions clearly demonstrates that chorismate/prephenate regulated DAHPSs must have independently arisen at least twice over the course of evolutionary history.32

We recently reported a structure of the L. monocytogenes N-terminal chorismate/prephenate regulated DAHPS.15,33 This structure reveals that the catalytic tetramer core is similar to the phenylalanine/tyrosine regulated enzyme. Two chorismate mutase-like extensions emerge on either side of this tetramer and interact to form a pair of dimers strikingly similar in structure to the chorismate mutase enzyme [Fig. 2(d)]. In this crystal, the two regulatory dimers awkwardly tilt away from the catalytic tetramer.

It remains unclear whether the asymmetry observed in the crystal structure captures the dominant solution state behavior of the regulatory domain or was arbitrarily selected for by crystal packing forces. In either case, the paucity of interactions between the discrete catalytic and regulatory domains combined with an analysis of patterns of sequence conservation suggests that chorismate/prephenate binding induces a large-scale regulatory domain repositioning and the creation of a stable inhibitory domain–domain interface.33 This proposed mechanism of inhibition also helps to explain the existence of the C-terminal chorismate/prephenate regulated DAHPS. As the model presumes that the domain linker assumes only indirect involvement in inhibition—solely functioning to ensure domain proximity—the chorismate mutase-like domain can be tethered to either end of the enzyme with minimal consequence on regulatory function. Nevertheless, a complete understanding of inhibition will ultimately require additional structural information about the inhibited states of the two chorismate/prephenate regulated variants.

Interestingly, it is not only the C- and N-terminally chorismate/prephenate regulated enzymes that bear a resemblance. Reflecting their close phylogenetic relationship, the chorismate/prephenate regulated enzyme is architecturally similar to its phenylalanine/tyrosine regulated cousin (Fig. 2). The catalytic tetramer is nearly identical within these two type Iβ regulatory subclasses. Moreover, both enzymes contain discrete N-terminal regulatory domains that minimally interact with the catalytic core in the enzymatically active state and likely undergo dramatic repositioning upon inhibitor binding. It is thus feasible that despite unique extensions and disparate inhibitors the two type Iβ regulatory subclasses employ a conserved mechanism of allostery—whether characterized by active site occlusion or catalytic domain induced conformational change.

Phenylalanine, Tyrosine, and Tryptophan Regulated Type Iα DAHPSs

With ∼20% sequence identity to type Iβ enzymes, the type Iα DAHPSs establish a distinct phylogenetic subtype.8 Sequencing efforts have revealed that organisms often encode multiple type Iα paralogs. For example, E. coli have three type Iα enzymes, whereas Saccharomyces cerevisiae have orthologs of two of these enzymes. Interestingly, despite high sequence conservation, each of the three Iα paralogs is allosterically regulated by a different aromatic amino acid (S. cerevisiae lack the tryptophan responsive variant).1,34

The phenylalanine regulated E. coli enzyme was the first DAHPS to be structurally characterized.16,35 This structure reveals that the enzyme is similar to the unregulated Iβ DAHPSs, but a ∼25 amino acid N-terminal helical extension and a ∼20 amino acid β-hairpin insertion modify the catalytic core [Fig. 3(a,b)]. The N-terminal helical extension establishes an interface for the formation of a distinct homotetramer by the pairing of unregulated type Iβ-like dimers [Fig. 3(c)] and, additionally, interacts with the β-hairpin insert to form a small cavity more than 15 Å from the active site [Fig. 3(b), top panel]. A complex with phenylalanine revealed that the inhibitor binds at this pocket and propagates conformational changes across the subunit.17,36 These conformational changes extend to the 2β-2α connecting loop, which directly interacts with substrate [Fig. 3(b), bottom panel). Interestingly, PEP continues to bind the inhibited conformational state but adopts a flipped, non-productive, orientation.36

Figure 3.

Overview of type Iα DAHPS structure and allostery. (A) Schematic representation of type Iα domain construction highlighting the characteristic N-terminal extension and β-hairpin insertion. (B) Top panel: cartoon representation of the phenylalanine regulated E. coli type Iα DAHPS monomer in complex with PEP (PDB code 1QR7). Bottom panel: structure of the monomer in complex with PEP and phenylalanine (PDB code 1KFL). Phenylalanine binding at the regulatory pocket induces subtle conformational changes in the 3β-3α connecting loop (green), which in turn affect the critical 2β-2α connecting loop (pink). (C) Surface representation of the distinct physiological tetramer. The two stable dimers are colored different shades of blue and the bound PEP is depicted in sphere representation. (D) A surface representation of the DAHPS monomer highlights phenylalanine binding to the allosteric pocket. The serine residue responsible for phenylalanine specificity is colored red. An interactive view is available in the electronic version of the article.

Shortly after structures of the phenylalanine regulated variant were described a structure of the S. cerevisiae tyrosine regulated DAHPS was published.18,37 This enzyme forms a homodimer similar to the unregulated type Iβ enzyme. A comparison to the phenylalanine regulated E. coli enzyme revealed a high degree of structural similarity (RMSD = 0.4 Å over 290 Cα atoms), suggesting that the two Iα variants employ related mechanisms of inhibition.37 An analysis of the allosteric binding site showed that a serine in the characteristic Iα subtype β-hairpin insert is replaced by a glycine in the tyrosine regulated enzyme [Fig. 3(d)]. The removal of the serine side chain expands the allosteric pocket, raising an obvious question about whether this increase in volume is what permits the larger tyrosine molecule to bind.

To test this hypothesis site directed mutants were generated and assayed.37 Converting the glycine to serine in the tyrosine regulated DAHPS drastically decreased tyrosine inhibition while increasing phenylalanine inhibition.37 Conversely, converting the serine to glycine in the phenylalanine regulated variant had the opposite effect.37 These results support the hypothesis that subtle differences in the binding pocket confer inhibitor specificity and hint at the evolutionary origin of these two distinct regulatory classes, suggesting that they may have arisen by a gene duplication event followed by a single functionally differentiating point mutation.37

Structures of the wild-type S. cerevisiae enzyme in complex with tyrosine and the glycine to serine mutant in complex with phenylalanine were later deposited to the PDB (accession codes 1OF619 and 1OG020) but, to this date, a manuscript describing the structures has not been published. An analysis of these structures reveals that in both cases inhibitor binding induces a set of conformational changes similar to those observed in the E. coli phenylalanine complex. The glycine to serine phenylalanine complex shows that if tyrosine bound in the same orientation in the mutant enzyme, its hydroxyl group would sterically clash with the serine side chain, thus confirming the hypothesis that regulatory pocket shrinkage in the phenylalanine regulated variant selectively occludes tyrosine binding. By contrast, how the presence of the serine side chain increases phenylalanine affinity is not readily apparent. Addressing this question will require a thorough analysis of the free energy of phenylalanine binding to the two regulatory pockets (± the serine side chain).

Although crystal structures have addressed key aspects of phenylalanine and tyrosine regulation, structures of the tryptophan regulated Iα variant have yet to be described. Such structural data will ultimately be necessary to develop a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism of type Iα allostery. However, in the absence of direct data, due to the degree of their sequence conservation, the phenylalanine and tyrosine regulated variants provide template structures that can be referenced to clarify the mechanism of tryptophan regulation.

If the tryptophan allosteric site is generally similar to the phenylalanine and tyrosine binding sites found in the related type Iα DAHPSs, it stands to reason that differences in the tryptophan binding pocket must be necessary to accommodate the bulkier side chain. Sequence alignments reveal that, among other differences, a prominently positioned glycine is substituted for a proline in the tryptophan regulated enzyme.38 Site directed mutagenesis studies performed on the S. cerevisiae tyrosine regulated enzyme revealed that mutating the glycine to proline rendered the enzyme more responsive to tryptophan and less responsive to tyrosine, suggesting that point mutation accounts for much, but not all, of the difference in inhibitor specificity.38

Synergistic Phenylalanine + Tyrosine + Tryptophan Regulated Type II DAHPS

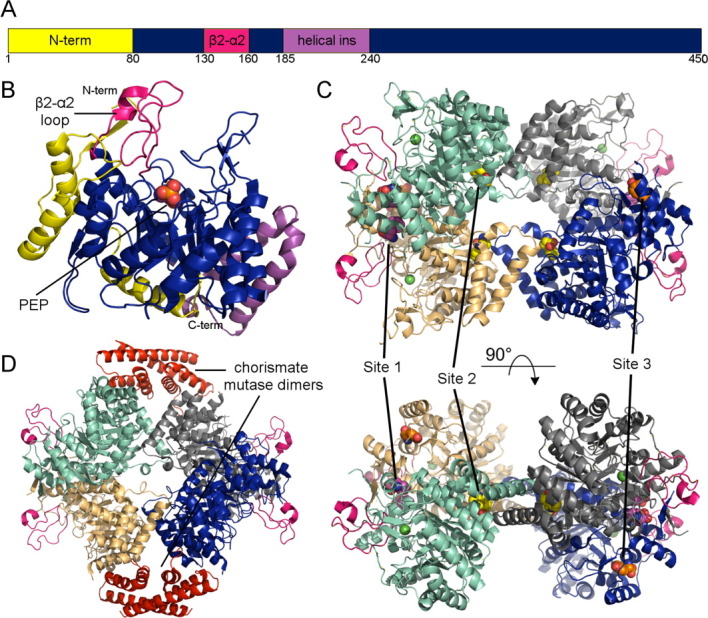

With less than 10% sequence homology, smaller type I and larger (∼450 amino acid) type II DAHPSs [Fig. 4(a)] bear only a distant relation. Although a subset of type II DAHPSs have been implicated in the biosynthesis of secondary (non-amino acid) metabolites,39 the majority of characterized type II enzymes appear to function in aromatic amino acid biosynthesis.6,9,40–43 Of these, several different feedback sensitivities been reported. Type II DAHPSs insensitive to chorismate and the aromatic amino acids,40 inhibited by tryptophan,6,41–43 and inhibited by chorismate + tryptophan9 have been described. At least one type II DAHPS seems to be subjected to a complex mechanism of regulatory control. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis type II enzyme exhibits an intricate inhibitory synergy. In isolation, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine are poor DAHPS inhibitors. However, various combinations of these pathway endpoints act together to efficiently shutdown DAHPS activity.44–46

Figure 4.

Overview of type II DAHPS structure and allostery. (A) Schematic representation of type II domain construction highlighting the three most prominent insertions (B) The M. tuberculosis DAHPS (PDB code 2B7O) monomer highlighting the characteristic type II inserts. (C) The type II DAHPS (PDB code 2YPQ) tetramer complexed with tryptophan (site 1, yellow) + phenylalanine (site 2, purple and site 3). The active site manganese ion is depicted as a green sphere. (D) Structure of the M. tuberculosis DAHPS + chorismate mutase (red) complex (PDB code 2W19). An interactive view is available in the electronic version of the article.

A crystal structure of the M. tuberculosis DAHPS reveals that type II enzyme forms a similar TIM-barrel core, which is decorated with two major and several minor type II specific insertions, including a considerable extension to the catalytically important 2β-2α connecting loop [Fig. 4(b)].21,47 Although the type II enzyme also forms a homotetramer, the assembly is unrelated to the type I quaternary structure [Fig. 4(c)]. Despite these differences the type II active site is very similar to its type I counterparts.

An initial study on the mechanism of M. tuberculosis DAHPS allostery reported complexes with phenylalanine, tryptophan, and phenylalanine + tryptophan.23,44 These structures, obtained by soaking the amino acids into unliganded crystals, revealed the existence of one tryptophan binding site (site 1) and two distinct phenylalanine binding sites (sites 2 and 3). However, subsequent co-crystallization experiments performed at a lower, more physiologically relevant, phenylalanine concentration suggested that only one of these phenylalanine binding sites (site 2) is functional [Fig. 4(c)].45 Interestingly, these complexes reveal that phenylalanine and tryptophan bind at some distance from each other and the active site. Despite the magnitude of this separation, amino acid binding induces only subtle conformational changes and thus neither the origin of synergy nor the mechanism of inhibition is immediately obvious.44

A set of follow up studies focused on identifying the mechanism of phenylalanine + tryptophan inhibition.45 Based on an analysis of protein temperature factors and supported by molecular dynamic simulations, it was argued that phenylalanine + tryptophan binding affects main chain flexibility, in particular increasing the mobility of the 2β-2α connecting loop.45 As substrate bound complexes had revealed that the 2β-2α connecting loop interacts with E4P,26,48 the increased mobility of the 2β-2α connecting loop in the inhibitor bound state was hypothesized to increase the entropic cost of substrate binding.45 As a perturbation of the 2β-2α connecting loop clearly underpins type Iα inhibition and may be mechanistically important for type Iβ inhibition, this proposed mechanism of type II inhibition suggests that the 2β-2α connecting loop may represent a conserved target across the multiple classes of DAHPS allostery.

Most recently, it was shown that in the presence of the other aromatic amino acids tyrosine contributes to the inhibitory synergy exhibited by the M. tuberculosis DAHPS.46 Crystal structures of the protein showed that tyrosine binds at the same sites (2 and 3) at which phenylalanine was previously observed.46 To determine which site was important for tyrosine inhibition, site directed mutants were generated with compromised binding sites 2 or 3. Kinetic and binding analysis of these mutants confirmed that a functional site 2 was essential for phenylalanine inhibition and demonstrated that a functional site 3 was required for tyrosine inhibition [Fig. 4(c)].46

A separate set of studies have shown that the M. tuberculosis DAHPS stably interacts with the organism's chorismate mutase enzyme.49 A crystal structure of this complex reveals chorismate mutase dimers associate with opposite sides of the DAHPS tetramer [Fig. 4(d)].22,49 Despite the distinct quaternary structure and non-covalent basis of interaction, this domain organization is reminiscent of the previously described chorismate/prephenate regulated type Iβ DAHPS [Fig. 2(d)]. Both structural assemblies are characterized by DAHPS tetramer cores sandwiched by external chorismate mutase-like dimers. However, while conferring chorismate/prephenate allosteric control appears to be the primary purpose of association in the type Iβ chorismate/prephenate regulated enzyme, the functional implications of association in the type II M. tuberculosis DAHPS are multifaceted.

Although it has been suggested that chorismate mutase association may similarly impart chorismate/prephenate control over DAHPS activity,49 this regulatory role has yet to be conclusively established. A clearer consequence of the interaction is the drastic increase in chorismate mutase activity (more than 100-fold). The magnitude of this enhancement argues that the association is essential for physiological chorismate mutase function.

Why might chorismate mutase activity be yoked to DAHPS? Perhaps because complex formation establishes a regulatory control over this important downstream branch point. Within the complex, chorismate mutase is synergistically inhibited by phenylalanine + tyrosine.49 Thus, in addition to the established phenylalanine + tryptophan + tyrosine DAHPS regulation, phenylalanine + tyrosine chorismate mutase regulation provides a second form of inhibitory synergy within the DAHPS/chorismate mutase functional complex. This design allows a single system to integrate intricate information about the concentration of the three most important pathway outputs to modulate flux through two critical pathway checkpoints.

Structural Analyses Provide Insight into DAHPS Evolution

Despite a clear-cut phylogenetic breakdown, the identification of defining type Iα, Iβ, and II functional characteristics has presented significant challenges. Kinetic rationalizations, suggesting systematic differences in metal cofactor dependency or substrate specificity, were initially proposed.8,10 However, subsequent efforts failed to identify any such differences and crystal structures revealed that the active site is highly conserved across class/subtype.9,40,47,50 Clear regulatory distinctions prompted speculation that classes/subtypes might be defined by allosteric inhibitor, but the identification of multiple type I regulatory subtypes eliminated this possibility.10,37,50 Revising the allostery-based hypothesis, it was most recently postulated that class/subtype distinctions might not relate to the inhibitor itself but rather the mechanism of inhibition.32 The analysis presented here is largely supportive of this mechanism based hypothesis. The type Iα structures reveal that the different regulatory subtypes result from minor alterations in the allosteric binding pocket, whereas structures of type Iβ enzymes suggest that the tyrosine and two chorismate/prephenate regulated proteins employ similar domain repositioning mechanisms of allostery.

In addition to allowing for the identification of commonalities that conceptually support the mechanism of inhibition hypothesis, structural characterization of the DAHPS subtypes provides insight into the basis of the phylogeny-allostery connection. The relationship between phylogenetic class/subtype and oligomeric assembly is quite striking. While the structurally characterized unregulated DAHPSs are possibly homodimeric, the type Iβ and type II enzymes are homotetrameric (Table I). Despite this seeming similarity, the two tetramers are formed by distinct assembly of the subunits. In this way, DAHPS phylogeny correlates with oligomeric organization. What is more, in both subclasses the organization of the tetramer is integrally linked to the mechanism of allostery. In the type Iβ enzymes, the tetrameric layout is crucial for positioning the regulatory domains so that they can cap the active sites in their inhibitor bound state. In the type II enzymes, the unique domain–domain interface interacts with the chorismate mutase enzyme and establishes the phenyalanine allosteric binding pocket.

In light of these observations it is clear that phylogeny, allostery, and quaternary structure fundamentally interrelate. Moreover, as quaternary structure is prerequisite for the mechanisms of allostery, it can be inferred that quaternary distinctions must evolutionarily predate the acquirement of type Iβ and type II allostery. This suggests that the development of distinct oligomeric assemblies may represent the defining event that set in motion divergent evolutionary courses that directly lead to the establishment of the discrete subtypes with their unique mechanisms of allostery.

Although this analysis provides insight into the likely sequence of events underpinning the parallel evolution of the DAHPS classes, why such allosteric diversity has persisted throughout evolutionary history remains an open question. The regulatory controls reviewed in this paper utilize distinct mechanisms to respond to different pathway outputs, yet perform similar feedback functions. If one of these regulatory mechanisms conferred a robust evolutionary advantage then it might be expected to outcompete the others and predominate. The persistence of a diverse set of regulatory mechanisms suggests that organismal variability may produce a wrinkle in feedback optimality. However, the factors that best suit a regulatory system for a particular organism remain entirely unclear. Correlating DAHPS regulatory control with other functional properties will be key in addressing the fascinating question of why evolutionary processes have produced and maintained such a diverse array of mechanisms of DAHPS allostery.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DAHPS

3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase

- E4P

erythrose 4-phosphate

- FL

ferredoxin-like

- KDO8PS

3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate synthase

- PEP

phosphoenolpyruvate

References

- 1.Bentley R. The shikimate pathway—a metabolic tree with many branches. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;25:307–384. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts F, Roberts CW, Johnson JJ, Kyle DE, Krell T, Coggins JR, Coombs GH, Milhous WK, Tzipori S, Ferguson DJ, Chakrabarti D, McLeod R. Evidence for the shikimate pathway in apicomplexan parasites. Nature. 1998;393:801–805. doi: 10.1038/31723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krappmann S, Lipscomb WN, Braus GH. Coevolution of transcriptional and allosteric regulation at the chorismate metabolic branch point of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13585–13590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240469697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho BK, Federowicz S, Park YS, Zengler K, Palsson BO. Deciphering the transcriptional regulatory logic of amino acid metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson GS, Rellos P, Davidson BE. Two promoters control the aroH gene of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;102:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90544-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker GE, Dunbar B, Hunter IS, Nimmo HG, Coggins JR. Evidence for a novel class of microbial 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), Streptomyces rimosus and Neurospora crassa. Microbiology. 1996;142:1973–1982. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen RA, Xie G, Calhoun DH, Bonner CA. The correct phylogenetic relationship of KdsA (3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate synthase) with one of two independently evolved classes of AroA (3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase) J Mol Evol. 2002;54:416–423. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0031-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subramaniam PS, Xie G, Xia T, Jensen RA. Substrate ambiguity of 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate synthase from Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the context of its membership in a protein family containing a subset of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthases. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:119–127. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.119-127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosset G, Bonner CA, Jensen RA. Microbial origin of plant-type 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthases, exemplified by the chorismate- and tryptophan-regulated enzyme from Xanthomonas campestris. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4061–4070. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.4061-4070.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birck MR, Woodard RW. Aquifex aeolicus 3-deoxy-D-manno-2-octulosonic acid 8-phosphate synthase: a new class of KDO 8-P synthase? J Mol Evol. 2001;52:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s002390010149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schofield LR, Anderson BF, Patchett ML, Norris GE, Jameson GB, Parker EJ. 2005. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1zco/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Shumilin IA, Zhou L, Wu J, Woodard RW, Bauerle R, Kretsinger RH. 2006. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1vs1/pdb.

- 13.Shumilin IA, Bauerle R, Wu J, Woodard RW, Kretsinger RH. 2004. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1rzm/pdb.

- 14.Cross PJ, Dobson RCJ, Patchett ML, Parker EJ. 2011. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb3pg9/pdb.

- 15.Halavaty AS, Light SH, Minasov G, Shuvalova L, Kwon K, Anderson WF. 2010. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb3nvt/pdb.

- 16.Shumilin IA, Kretsinger RH, Bauerle RH. 1999. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1qr7/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Shumilin IA, Zhao C, Bauerle R, Kretsinger RH. 2002. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1kfl/pdb.

- 18.Koenig V, Pfeil A, Heinrich G, Braus GH, Schneider TR. 2004. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1ofp/pdb.

- 19.Koenig V, Pfeil A, Heinrich G, Braus G, Schneider TR. 2004. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1of6/pdb.

- 20.Koenig V, Pfeil A, Heinrich G, Braus GH, Schneider TR. 2004. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb1og0/pdb.

- 21.Webby CJ, Baker HM, Lott JS, Baker EN, Parker EJ. 2005. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb2b7o/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Okvist M, Sasso S, Roderer K, Gamper M, Codoni G, Krengel U, Kast P. 2009. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb2w19/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Parker EJ, Jameson GB, Jiao W, Webby CJ, Baker EN, Baker HM. 2010. Protein Data Bank, DOI 10.2210/pdb3kgf/pdb.

- 24.Zhou L, Wu J, Janakiraman V, Shumilin IA, Bauerle R, Kretsinger RH, Woodard RW. Structure and characterization of the 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase from Aeropyrum pernix. Bioorg Chem. 2012;40:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schofield LR, Anderson BF, Patchett ML, Norris GE, Jameson GB, Parker EJ. Substrate ambiguity and crystal structure of Pyrococcus furiosus 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase: an ancestral 3-deoxyald-2-ulosonate-phosphate synthase? Biochemistry. 2005;44:11950–11962. doi: 10.1021/bi050577z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shumilin IA, Bauerle R, Wu J, Woodard RW, Kretsinger RH. Crystal structure of the reaction complex of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Thermotoga maritima refines the catalytic mechanism and indicates a new mechanism of allosteric regulation. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:455–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radaev S, Dastidar P, Patel M, Woodard RW, Gatti DL. Structure and mechanism of 3-deoxy-D-manno-octulosonate 8-phosphate synthase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9476–9484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cross PJ, Dobson RC, Patchett ML, Parker EJ. Tyrosine latching of a regulatory gate affords allosteric control of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:10216–10224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cross PJ, Allison TM, Dobson RC, Jameson GB, Parker EJ. Engineering allosteric control to an unregulated enzyme by transfer of a regulatory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2111–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217923110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nester EW, Lorence JH, Nasser DS. An enzyme aggregate involved in the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids in Bacillus subtilis. Its possible function in feedback regulation. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1553–1563. doi: 10.1021/bi00857a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J, Sheflyan GY, Woodard RW. Bacillus subtilis 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase revisited: resolution of two long-standing enigmas. Biochem J. 2005;390:583–590. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J, Woodard RW. New insights into the evolutionary links relating to the 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase subfamilies. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4042–4048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Light SH, Halavaty AS, Minasov G, Shuvalova L, Anderson WF. Structural analysis of a 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase with an N-terminal chorismate mutase-like regulatory domain. Protein Sci. 2012;21:887–895. doi: 10.1002/pro.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen RA, Nasser DS. Comparative regulation of isoenzymic 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthetases in microorganisms. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:188–196. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.1.188-196.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shumilin IA, Kretsinger RH, Bauerle RH. Crystal structure of phenylalanine-regulated 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. Structure. 1999;7:865–875. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shumilin IA, Zhao C, Bauerle R, Kretsinger RH. Allosteric inhibition of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase alters the coordination of both substrates. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00545-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartmann M, Schneider TR, Pfeil A, Heinrich G, Lipscomb WN, Braus GH. Evolution of feedback-inhibited beta /alpha barrel isoenzymes by gene duplication and a single mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:862–867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337566100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helmstaedt K, Strittmatter A, Lipscomb WN, Braus GH. Evolution of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase-encoding genes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9784–9789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504238102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silakowski B, Kunze B, Muller R. Stigmatella aurantiaca Sg a15 carries genes encoding type I and type II 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthases: involvement of a type II synthase in aurachin biosynthesis. Arch Microbiol. 2000;173:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s002030000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webby CJ, Patchett ML, Parker EJ. Characterization of a recombinant type II 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Helicobacter pylori. Biochem J. 2005;390:223–230. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuart F, Hunter IS. Purification and characterization of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Streptomyces rimosus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1161:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90215-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nimmo GA, Coggins JR. Some kinetic-properties of the tryptophan-sensitive 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase from Neurospora-crassa. Biochem J. 1981;199:657–665. doi: 10.1042/bj1990657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorisch H, Lingens F. 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase of Streptomyces aureofaciens tu 24. 2. Repression and inhibition by tryptophan and tryptophan analogues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1971;242:630–636. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webby CJ, Jiao W, Hutton RD, Blackmore NJ, Baker HM, Baker EN, Jameson GB, Parker EJ. Synergistic allostery, a sophisticated regulatory network for the control of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30567–30576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.111856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiao W, Hutton RD, Cross PJ, Jameson GB, Parker EJ. Dynamic cross-talk among remote binding sites: The molecular basis for unusual synergistic allostery. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:716–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blackmore NJ, Reichau S, Jiao W, Hutton RD, Baker EN, Jameson GB, Parker EJ. Three sites and you are out: Ternary synergistic allostery controls aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol. 2012;S0022–2836:00952–00957. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Webby CJ, Baker HM, Lott JS, Baker EN, Parker EJ. The structure of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals a common catalytic scaffold and ancestry for type I and type II enzymes. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konig V, Pfeil A, Braus GH, Schneider TR. Substrate and metal complexes of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae provide new insights into the catalytic mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2004;337:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sasso S, Okvist M, Roderer K, Gamper M, Codoni G, Krengel U, Kast P. Structure and function of a complex between chorismate mutase and DAHP synthase: efficiency boost for the junior partner. EMBO J. 2009;28:2128–2142. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu J, Howe DL, Woodard RW. Thermotoga maritima 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP) synthase: the ancestral eubacterial DAHP synthase? J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27525–27531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]