Abstract

Dehydroquinate dehydratase (DHQD) catalyzes the third reaction in the biosynthetic shikimate pathway. Type I DHQDs are members of the greater aldolase superfamily, a group of enzymes that contain an active site lysine that forms a Schiff base intermediate. Three residues (Glu86, His143, and Lys170 in the Salmonella enterica DHQD) have previously been proposed to form a triad vital for catalysis. While the roles of Lys170 and His143 are well defined—Lys170 forms the Schiff base with the substrate and His143 shuttles protons in multiple steps in the reaction—the role of Glu86 remains poorly characterized. To probe Glu86′s role, Glu86 mutants were generated and subjected to biochemical and structural study. The studies presented here demonstrate that mutant enzymes retain catalytic proficiency, calling into question the previously attributed role of Glu86 in catalysis and suggesting that His143 and Lys170 function as a catalytic dyad. Structures of the Glu86Ala (E86A) mutant in complex with covalently bound reaction intermediate reveal a conformational change of the His143 side chain. This indicates a predominant steric role for Glu86, to maintain the His143 side chain in position consistent with catalysis. The structures also explain why the E86A mutant is optimally active at more acidic conditions than the wild-type enzyme. In addition, a complex with the reaction product reveals a novel, likely nonproductive, binding mode that suggests a mechanism of competitive product inhibition and a potential strategy for the design of therapeutics.

Keywords: dehydroquinate dehydratase, nonproductive binding, Schiff base, shikimate pathway

Introduction

Dehydroquinate dehydratase (DHQD), the third enzyme in the biosynthetic shikimate pathway, catalyzes the conversion of dehydroquinate (DHQ) to dehydroshikimate (DHS). Two nonhomologous types of DHQDs are known to exist.1,2 Members of the greater Class I aldolase superfamily,3 Type I DHQDs establish a Schiff base with the substrate that acts as an electron sink to promote the dehydration.4,5 In contrast, the Type II DHQDs employ an unrelated noncovalent intermediate mechanism that contains an enolate intermediate.6,7

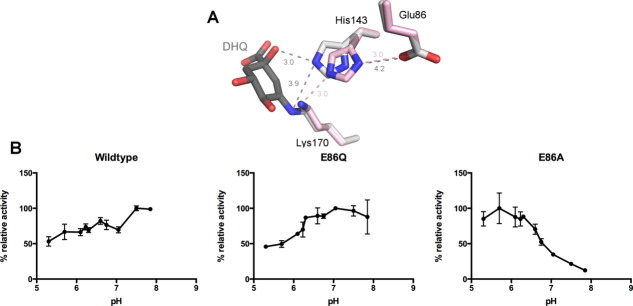

Previously, three active site residues of the Salmonella enterica Type I DHQD (seDHQD) have been hypothesized to establish a catalytic triad [Fig. 1(A)].8 Within this triad, Lys170 forms the covalent Schiff base with the substrate and His143 acts as the general acid and general base that catalyzes multiple proton transfer events within the formation and hydrolysis of the Schiff base and the catalytic dehydration event.9–12 The final member of the triad, Glu86, hydrogen bonds with His143 but its role in catalysis remains unclear.

Figure 1.

(A) Superposition of seDHQD unliganded (pink, PDB code: 3L2I) and bound DHQ reaction intermediate (gray, PDB code: 3M7W) structures, displaying the putative catalytic triad: Glu86, His143, and Lys170. Distances are shown in angstroms and colored by structure. (B) Maximal DHQD activity by pH of wild-type, E86Q, and E86A variants. Activity is normalized to the most active pH for each variant. Standard deviations are indicated as error bars.

Membership of Glu86 in the triad was originally inferred from the residue's prominent position and the pH dependence of enzymatic activity—a drop in DHQD activity at acidic pH was attributed to the protonation of Glu86.8 Further fueling speculation about Glu86′s functional involvement in catalysis was the similarity of the Glu86-His143-Lys170 network to the analogous serine protease catalytic triad.2 Subsequent crystal structures revealed that the interaction between Glu86 and His143 present in the unliganded state [pink, Fig. 1(A)] is broken upon the formation of the Schiff base intermediate [gray, Fig. 1(A)], as His143 rotates to interact with the DHQ leaving group.13 Thus, a plausible role for Glu86 is to participate in the shuttling of protons between His143, Lys170, and leaving group in Schiff base formation and hydrolysis and/or the catalytic dehydration. Despite this conceptual framework, the role of Glu86 has never been experimentally addressed. Therefore, to probe the functional role of Glu86, biochemical and structural studies of seDHQD Glu86 mutants were undertaken.

Results

E86A and E86Q kinetics and E86A unliganded structure

SeDHQD Glu86Ala (E86A) and Glu86Gln (E86Q) mutants were generated and their enzymatic activity assayed. Consistent with the expectation of functional involvement of Glu86 in catalysis but not substrate binding, values for kcat but not Km are significantly altered in the mutants. The E86Q mutation rather modestly affects kcat, decreasing it by a factor of 4 (Table I). The E86A mutation has a greater effect, reducing kcat 17-fold (Table I).

Table I.

Kinetic Characterization of DHQD Variants (pH 7.5)

| kcat (s–1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (s—1 μM–1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 310 ± 12 | 53 ± 7 | 5.8 |

| E86Q | 78 ± 1.7 | 30 ± 2 | 2.6 |

| E86A | 18 ± 0.6 | 46 ± 5 | 0.4 |

Errors calculated by fitting of the kinetic data to Michaelis-Menten equation and expressed as ±standard error.

Interestingly, the E86A but not E86Q variant displays a significant shift in pH optimum relative to the wild-type enzyme. The wild-type and E86Q variants are most active at slightly basic pH (7.5), whereas the E86A variant is maximally active at acidic pH (5.7), with only marginal activity above pH 7.5 [Fig. 1(B)].

To understand the effects of the E86A mutation on the seDHQD pH profile and the role of Glu86 in the reaction, a crystal structure of the unliganded E86A mutant was determined at a resolution of 1.50 Å (Table II). Superposition to the previously described wild-type seDHQD structure reveals no global changes in structure (RMSD = 0.21 Å over 222 Cα atoms). At the site of the mutation, two ordered water molecules are observed in the space opened by the E86A mutation and the His143 side chain is slightly displaced from its wild-type conformation.

Table II.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for E86A Structuresa

| Unliganded | DHQ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| “cocrystallized” | “soaked” | DHQ | |

| PDB code | 4GUF | 4GUG | 4GUH |

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P1 | P21 | P212121 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | a = 36.77 | a = 45.70 | a = 36.84 |

| b = 45.50 | b = 64.20 | b = 71.67 | |

| c = 81.06 | c = 81.05 | c = 171.75 | |

| α, β, γ (degrees) | α = 93.90 | α = 90.00 | α = 90.00 |

| β = 101.41 | β = 93.89 | β = 90.00 | |

| γ = 105.90 | γ = 90.00 | γ = 90.00 | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.00–1.50 | 30.00–1.62 | 30.00–1.95 |

| (1.53–1.50) | (1.65–1.62) | (1.98–1.95) | |

| Completeness (%) | 94.7 (86.5) | 97.0 (93.5) | 99.8 (100.0) |

| Redundancy | 2.3 (2.1) | 3.8 (3.6) | 7.1 (6.9) |

| [I/σ(I)] | 13.9 (2.7) | 21.2 (2.6) | 21.5 (3.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 5.6 (43.4) | 5.4 (52.5) | 8.1 (61.1) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.43–1.50 | 29.86–1.62 | 28.63–1.95 |

| (1.54–1.50) | (1.66–1.62) | (2.00–1.95) | |

| No. of reflections | 74584 (5073) | 57824 (4078) | 34213 (1655) |

| R-factor (Rwork/Rfree) b | 16.7/19.1 | 17.5/20.8 | 19.0/24.7 |

| Protomers/asymmetric unit | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 3541 | 3561 | 3824 |

| Waters | 548 | 359 | 243 |

| DHS | — | 23 | 24 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 21.2 | 36.8 | 35.1 |

| Waters | 33.0 | 40.4 | 36.9 |

| DHS | — | 28.6 | 31.1 |

| R.M.S. deviations | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.50 | 1.97 | 1.44 |

| Ramachandran analysis | |||

| Favored regions (%) | 97.9 | 97.9 | 97.0 |

| Allowed regions (%) | 99.5 | 100 | 100 |

| Disallowed regions (%) | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

Highest resolution shell in parenthesis.

Definition of Rwork, Rfree: R = Σhkl | | Fobs | – | Fcalc | | / Σhkl |Fobs|, where hkl are the reflection indices used in refinement for Rwork, and 5% not used in refinement for Rfree. Fobs and Fcalc are structure factors deduced from measured intensities or calculated from the model, respectively.

E86A-complexes

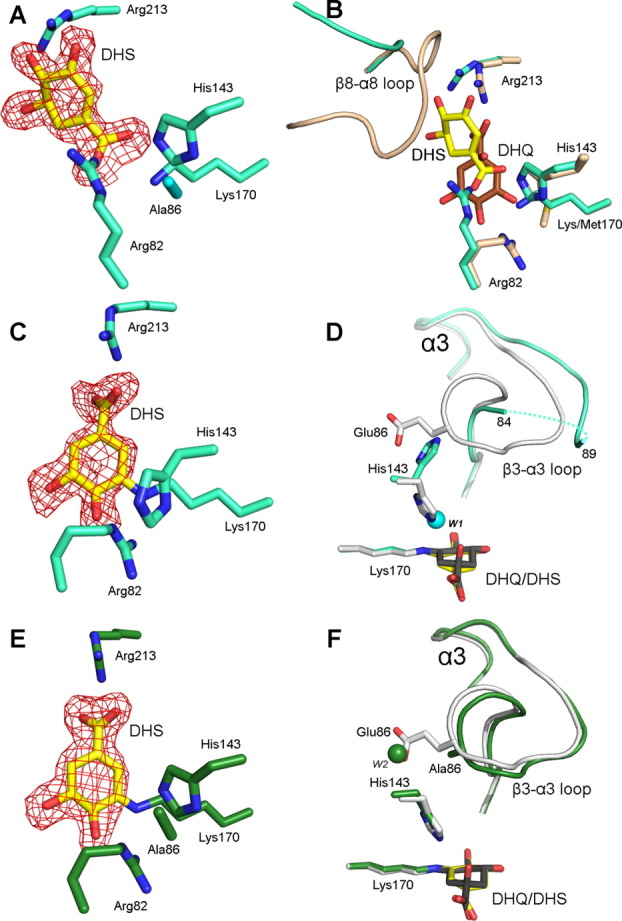

To better understand the role of Glu86 in catalysis, structures of E86A reaction complexes were pursued. To this end, two crystallization strategies were employed: cocrystallizing the E86A mutant in the presence of 3 mM of the reaction substrate, DHQ, and soaking a preformed unliganded crystal in 25 mM DHQ. Both strategies yielded crystal structures with reaction product, DHS, electron density at the active site, indicating that catalytic turnover has occurred (Table II). Interestingly, distinct DHS binding modes are evident within the “cocrystallized” and “soaked” structures and between the two protomers in the crystallographic asymmetric unit of the cocrystallized complex.

In the first protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex, DHS binds noncovalently in a flipped orientation relative to that observed in previous seDHQD wild-type structures [Fig. 2(A)].13 Despite interacting with the same active site residues, DHS binding differs markedly from all previously described reaction complexes [Fig. 2(B)]. The Schiff base-forming Lys170 interacts with the DHS 1-carboxyl and the Arg82 guanidinium group is rotated ∼ 90° to a position where it too interacts with the 1-carboxyl. The functionally important loop that connects β-strand 8 to α-helix 8 (β8-α8 loop), which is observed open and partially disordered in unliganded structures but closed over the active site and hydrogen bonding with the reacting molecule in complexed structures,14 assumes an intermediate conformational state. The β8-α8 loop residue, Gln236, which mutagenesis studies demonstrate is vital for efficient substrate binding and catalysis,14 adopts an intermediate conformation where it interacts with DHS 4- and 5-hydroxyl groups, while the N-terminal portion of the β8-α8 loop (Lys229-Ala233) is disordered. Notably, the observed binding mode is incompatible with the closed conformation of the β8-α8 loop, which would sterically clash with the substrate [Fig. 2(B)].

Figure 2.

Three modes of DHS binding from two E86A mutant crystal structures. (A) Stick model of the first protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex. The product, DHS, is colored yellow in all panels. Select active site residues are colored cyan. Throughout the figure, fo-fc electron density maps (red) calculated with ligand omitted from the model are contoured at 2.5σ. (B) Superposition of the first protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex (cyan) to the K170M-DHQ complex (beige, PDB code: 3NNT). DHQ is colored brown. (C) Stick model of second protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex. (D) Superposition of the second protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex to wild-type the Schiff base bound reaction intermediate structure (light gray, PDB code: 3M7W). The ordered water molecule (W1) in the E86A-DHS structure situated in the position vacated by the His143 imidazole is represented as a cyan sphere. A dashed line traces disordered residues Lys85-Gly88. (E) Stick model of the soaked E86A-DHS complex (green). (F) Superposition of the soaked E86A-DHS complex (green) to the wild-type Schiff base bound reaction intermediate (light gray). DHQ is colored dark gray. The ordered water molecule (W2) in the E86A-DHS structure situated in the position vacated by the Glu86 side chain is represented as a green sphere.

In the second protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex, DHS is covalently linked to Lys170 in its Schiff base bound intermediate state [Fig. 2(C)]. A comparison to previously reported Schiff base reaction complexes reveals a high degree of similarity in the position of the reaction intermediate but a significant divergence in neighboring residues [Fig. 2(D)]. In this E86A complex, the His143 side chain has flipped outward and its imidazole group is situated where the Glu86 side chain is found in the wild-type structure. An ordered water molecule (W1) assumes the position now vacated by the His143 imidazole moiety. This His143 conformation is inconsistent with the β3-α3 loop conformation present in the wild-type structure. Indeed, the Ala86 containing β3-α3 loop is partially disordered in this protomer [Fig. 2(D)].

In the soaked E86A-DHS complex, DHS assumes identical binding modes within the two protomers of the asymmetric unit. In both protomers, DHS has formed a Schiff base intermediate state similar to the one observed in the second protomer of the cocrystallized complex [Fig. 2(E)]. However, perhaps the result of distinct crystal packing in this crystal form, this structure differs from the cocrystallized complex in that His143 and the β3-α3 loop retain their wild-type conformation [Fig. 2(F)]. The soaked E86A-DHS complex thus demonstrates that the intermediate state conformational behavior observed in the cocrystallized complex is not a universal feature of the E86A mutant.

Discussion

Distinct kinetic and structural properties of E86A mutant

Kinetic analyses reveal that the two Glu86 mutants are reasonably active. While Glu86 clearly influences catalysis, it is significantly less important than the other members of the so-called catalytic triad, Lys170 and His143—mutants of which exhibit >10,000-fold reduction in activity.9,13 Considering that the Glu86 mutants display activity comparable to mutants of other residues that clearly do not directly participate in catalysis,9,14 grouping Glu86 with the catalytically indispensable Lys170 and His143 seems inappropriate. Thus, we propose that the Type I DHQD catalytic apparatus consists of a Lys170/His143 dyad, a similar arrangement as observed in other Schiff base forming enzymes.3

While demonstrating the dispensability of Glu86, the Glu86 mutants bear interesting kinetic distinctions from the wild-type enzyme (in particular, a lower pH optimum for the E86A mutant) and the crystal structures provide hints as to the possible roles of Glu86. The near wild-type activity of the E86Q mutant (kcat/Km reduced only by a factor of 2, Table I) suggests that the primary role of the Glu86 (retained by Gln86 in the E86Q mutant) is to sterically orient His143. In the E86A variant, the space opened up by the smaller side chain allows for mispositioning of His143 [as seen in protomer 2 of the cocrystallized complex, Fig. 2(D)]. Given the important general acid/general base role of His143 in catalysis, this conformational change could account for the more dramatic effect of the E86A mutation, as compared to the E86Q mutation, on catalytic rate.

Based upon the small activity loss of the E86Q variant, Glu86 may also have an ionization function, that is, the ability to donate and accept a proton from His143. As E86Q is significantly more active than E86A, this function must be less important than the steric function. However, it may explain the perturbed pH-rate profile of the E86A variant. Specifically, the lower pH optimum for the E86A variant may result from one of two prominently positioned water molecules observed in the void left by the mutation. In the second protomer of the cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex, an ordered water molecule [W1 in Fig. 2(D)] assumes the position vacated by the His143 imidazole. In the soaked E86A-DHS structure, an ordered water molecule [W2 in Fig. 2(F)] assumes the position vacated by the Glu86 carboxylate. The assumption of a general acid role in catalysis by either of these waters could account for the higher activity of the E86A variant at acidic pH.

Significance of the noncovalent DHS binding mode

The observation of a novel noncovalent binding mode in the first protomer of the cocrystallized complex structure was unexpected and its significance is not entirely clear. One possibility is that the cocrystallized complex represents a nonproductive conformation that is off the productive reaction trajectory. Contacting only critical active site residues, it is possible that this binding mode results from an unavoidable property of the near optimally evolved catalytic apparatus, and therefore has no functional purpose but also negligible effect on relative catalytic output. On the other hand, it is possible that this binding mode evolved to establish competitive product inhibition, thereby conferring a regulatory control over DHQD activity.

At the very least, the noncovalent complex is interesting in that it demonstrates the existence of a stable open β8-α8 loop binding mode [Fig. 2(B)]. Because DHQD activity is essential in pathogenic bacteria but lacks a homologous mammalian counterpart, the enzyme has been considered a viable target for the design of novel antimicrobials.15,16 However, finding a molecule that binds with high affinity to the small, enclosed DHQD active site presents a considerable drug discovery challenge. The open β8-α8 loop conformation provides a window for expanding a molecule to extend out of the active site. In this way, the demonstration that a small molecule can bind to the active site while the loop adopts its open conformation provides a proof of principle, illustrating the feasibility of targeting the more tractable conformational state, and a potential starting point for future inhibitor design efforts.

Methods

Site-directed mutagenesis, protein expression, and purification

E86A and E86Q mutants were produced using the QuikChange XL Site-Direct Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) and conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's manual. Expression and purification protocols were followed as described for the wild-type protein.13,14

DHQD activity assay

Activity assays were performed in 100 mM potassium phosphate at 37°C. DHQD activity was spectroscopically assayed by following the increase in absorbance (λ = 234) resulting from the formation of the conjugated enone carboxylate in DHS (ε = 12 mM–1 cm–1).13,14,17,18 Reaction rates were measured in triplicate and kinetic parameters calculated by fitting this data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using the enzyme kinetics module in SigmaPlot version 8.02.

Protein crystallization and data collection

Sitting drop crystallization experiments were performed at room temperature by adding 1 μL of enzyme (7.5 mg/mL) to 1 μL of reservoir. Cocrystallization with 3 mM DHQ yielded the cocrystallized E86A-DHS structure. A ∼ 5-min soak in reservoir solution + 25 mM DHQ yielded the soaked E86A-DHS structure. Crystals were harvested from conditions containing: 0.2M sodium chloride and 20% PEG 3350 (unliganded structure); 0.19M sodium chloride and 17.9% PEG 3350 (cocrystallized E86A-DHS complex); 0.1M MIB buffer (pH 9) and 25% PEG 1500 (soaked E86A-DHS complex). Note that the unliganded crystal used for the soaking experiment was generated in a different condition than the crystal used to determine the unliganded structure and thus their difference in crystal form cannot be attributed to the soaking regime. Crystals were frozen in liquid nitrogen and diffraction data were collected at 100°K at the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team at the Advance Photon Source, Argonne, IL.

Structure determination and refinement

Data were indexed, integrated, and scaled in HKL-3000.19 Structures were solved by molecular replacement in Phaser,20 with the unliganded DHQD structure (PDB code: 3L2I) serving as the search model. Structures were refined with Refmac.21 Models displayed in Coot22 were manually corrected based on electron density maps. Structure figures were prepared in the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3 (Schrödinger, LLC).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DHQ

Dehydroquinate

- DHQD

DHQ dehydratase

- DHS

dehydroshikimate

- seDHQD

Salmonella enterica DHQD

REFERENCES

- 1.Kleanthous C, Deka R, Davis K, Kelly SM, Cooper A, Harding SE, Price NC, Hawkins AR, Coggins JR. A comparison of the enzymological and biophysical properties of two distinct classes of dehydroquinase enzymes. Biochem J. 1992;282:687–695. doi: 10.1042/bj2820687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gourley DG, Shrive AK, Polikarpov I, Krell T, Coggins JR, Hawkins AR, Isaacs NW, Sawyer L. The two types of 3-dehydroquinase have distinct structures but catalyze the same overall reaction. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:521–525. doi: 10.1038/9287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi KH, Lai V, Foster CE, Morris AJ, Tolan DR, Allen KN. New superfamily members identified for Schiff-base enzymes based on verification of catalytically essential residues. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8546–8555. doi: 10.1021/bi060239d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler JR, Alworth WL, Nugent MJ. Mechanism of dehydroquinase catalyzed dehydration. I. Formation of a Schiff-base intermediate. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:1617–1618. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson KR, Rose IA. Absolute stereochemical course of citric acid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1963;50:981–988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.5.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JM, Gonzalez-Bello C, Kleanthous C, Hawkins AR, Coggins JR, Abell C. Evidence from kinetic isotope studies for an enolate intermediate in the mechanism of type II dehydroquinases. Biochem J. 1996;319:333–336. doi: 10.1042/bj3190333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker EJ, Bello CG, Coggins JR, Hawkins AR, Abell C. Mechanistic studies on type I and type II dehydroquinase with (6R)- and (6S)-6-fluoro-3-dehydroquinic acids. Bioorgan Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leech AP, Boetzel R, McDonald C, Shrive AK, Moore GR, Coggins JR, Sawyer L, Kleanthous C. Re-evaluating the role of His-143 in the mechanism of type I dehydroquinase from Escherichia coli using two-dimensional 1H,13C NMR. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9602–9607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leech AP, James R, Coggins JR, Kleanthous C. Mutagenesis of active site residues in type I dehydroquinase from Escherichia coli. Stalled catalysis in a histidine to alanine mutant. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25827–25836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yao Y, Li ZS. The reaction mechanism for dehydration process catalyzed by type I dehydroquinate dehydratase from gram-negative Salmonella enterica. Chem Phys Lett. 2012;519/520:100–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan Q, Yao Y, Li ZS. New insights into the mechanism of the Schiff base formation catalyzed by type I dehydroquinate dehydratase from S. enterica. Theoret Chem Acc. 2012:131. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25605c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao Y, Li ZS. New insights into the mechanism of the Schiff base hydrolysis catalyzed by type I dehydroquinate dehydratase from S. enterica: a theoretical study. Organ Biomol Chem. 2012;10:7037–7044. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25605c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Light SH, Minasov G, Shuvalova L, Duban ME, Caffrey M, Anderson WF, Lavie A. Insights into the mechanism of type I dehydroquinate dehydratases from structures of reaction intermediates. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3531–3539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Light SH, Minasov G, Shuvalova L, Peterson SN, Caffrey M, Anderson WF, Lavie A. A conserved surface loop in type I dehydroquinate dehydratases positions an active site arginine and functions in substrate binding. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2357–2363. doi: 10.1021/bi102020s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cersini A, Salvia AM, Bernardini ML. Intracellular multiplication and virulence of Shigella flexneri auxotrophic mutants. Infect Immun. 1998;66:549–557. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.549-557.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller IA, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Desilva L, Joysey HS, Hormaeche C. Bacteriophage-P22 as a vehicle for transducing cosmid gene banks between smooth strains of Salmonella typhimurium—use in identifying a role for arod in attenuating virulent Salmonella strains. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;215:312–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00339734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri S, Lambert JM, Mccoll LA, Coggins JR. Purification and characterization of 3-dehydroquinase from Escherichia-coli. Biochem J. 1986;239:699–704. doi: 10.1042/bj2390699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noble M, Sinha Y, Kolupaev A, Demin O, Earnshaw D, Tobin F, West J, Martin JD, Qiu C, Liu WS, DeWolf WE, Jr, Tew D, Goryanin II. The kinetic model of the shikimate pathway as a tool to optimize enzyme assays for high-throughput screening. Biotech Bioengin. 2006;95:560–573. doi: 10.1002/bit.20772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Macromol Cryst. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Cryst. 2005;D61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Lebedev A, Wilson KS, Dodson EJ. Efficient anisotropic refinement of macromolecular structures using FFT. Acta Cryst. 1999;D55:247–255. doi: 10.1107/S090744499801405X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]