Abstract

Molecules containing multiple lanthanide ions have unique potential in applications for medical imaging including the areas of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and fluoresence imaging. The study of multilanthanide complexes as contrast agents for MRI and as biologically responsive fluorescent probes has resulted in an improved understanding of the structural characteristics that govern the behavior of these complexes. This review will survey the last five years of progress in multinuclear lanthanide complexes with a specific focus on the structural parameters that impact potential medical imaging applications. The patents cited in this review are from the last five years and describe contrast agents that contain multiple lanthanide ions.

Keywords: Contrast agent, coordination chemistry, dimetallic, dinuclear, gadolinium, lanthanide, luminescence, macrocycle, macromolecule, magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, multilanthanide, optical imaging, PARACEST, rare earth, relaxivity, sensitized luminescence, trinuclear

INTRODUCTION

Multimetallic lanthanide (Ln) complexes are widely studied because of their magnetic and luminescent properties. Due to these properties, multilanthanide complexes are potentially useful in nanomedicine, provided the complexes are chemically and kinetically inert, nontoxic, monodisperse, and well characterized. While many multimetallic lanthanide complexes have been studied, few meet all of these requirements [1–4]. The focus of this review is discrete multilanthanide complexes reported during the last five years that exhibit covalently linked chelates known to bind lanthanide ions tightly (log KGdL > 18). Generally, this category of coordination compounds falls in an intermediate molecular weight range (1–6 kDa) and exhibits relatively short metal-metal distances (<600 nm). Characterization of these discrete complexes allows for structure-function relationships to be definitively analyzed, and these relationships are important for understanding larger systems including polymers and dendrimers [5–21]. The scope of lanthanide-containing materials is too vast to be adequately described in a single review article; consequently, this review will not address dendrimeric, polymeric, or bioconjugated poly lanthanide complexes. Reviews for these types of molecules are available elsewhere [1, 4, 22–27].

A unique feature of the lanthanides is that the most stable oxidation state for all of these elements is +3, yet they display a wide range of magnetic and luminescent properties over a relatively narrow size range (the +3 ionic radii of elements 58–71 are in the range of 102-86 pm) [28]. A consequence of these properties is that lanthanide ions tend to form nearly isostructural complexes that commonly exhibit coordination numbers of 8–10. From a synthetic perspective, the near-isostructural nature of lanthanides is advantageous because a single ligand can be used to generate lanthanide complexes for a variety of medical applications including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), optical imaging, and immunogenic assays. With such a wide variety of properties incorporated into almost isostructural elements, ligand design is a key focus for researchers interested in exploring applications of these elements.

Two applications for which multilanthanide complexes are studied include contrast agents for MRI and luminescent imaging probes. This review will cover these two topics with a brief introduction to each topic preceding a detailed discussion of the ligand design and multilanthanide complexes that have been investigated for each application. The article will conclude with a final summary of the contributions made to each field and a discussion of the future potential for this class of complexes.

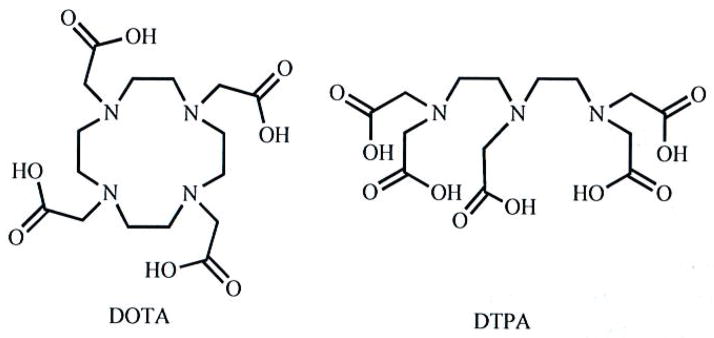

MULTIMERIC LIGAND DESIGN

A variety of ligand motifs have been used to form multimetallic lanthanide complexes for medical applications. Discussion of the specific syntheses of multimeric ligands is beyond the scope of this article. The techniques employed have been developed in monomeric ligand syntheses that are thoroughly reviewed elsewhere [29]. As a result of the extensive research of monomeric polyamino polycarboxylates, the majority of multimeric ligands are derivatives of the monomeric chelators diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) (Fig. 1). Both DOTA and DTP A form kinetically inert complexes with lanthanides under physiological conditions (kd = 1.2 × 103 and 21 s−1 for GdDTPA and GdDOTA, respectively), and the gadolinium complexes of these ligands are clinically approved contrast agents for MRI [2, 3]. While this review is not focused on monometallic lanthanide complexes, the basic chemistry of these complexes strongly influences the design of ligands for multilanthanide complexes. Thus, a brief discussion of the properties of monomeric complexes will be useful in understanding the design of their multimeric analogs.

Fig. 1.

Molecular structures of macrocyclic DOTA and acyclic DTPA.

Most kinetically inert lanthanide complexes contain polydentate chelates with nitrogen- and oxygen-based donors [2, 3]. The majority of these ligands are octadentate, leaving one coordination site for a solvent molecule or other ligand to bind to the metal ion. Two factors contribute to the inertness of these complexes: (1) the chelate effect and (2) electrostatic attraction. Furthermore, macrocyclic-based ligands such as DOTA gain additional stability over their acyclic counterparts due to the macrocyclic effect. Consequently, many multimeric ligands feature macrocyclic chelates, and a common scaffold for these chelates is 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (cyclen).

Due to the success of GdDOTA as a contrast agent for MRI, N-functionalized-cyclen-based chelates are common in multilanthanide complexes. Cyclen has been functionalized with a variety of substituents including acetates, amides, phosphonates, alcohols, and ketones [30–33]. Due to the difference in basicity and nucleophilicity of its four nitrogen atoms, cyclen can be selectively functionalized such that one, two, or three nitrogens remain available for substitution after one substituent is attached [29]. Thus, ligands can be designed in which three substituents serve as donors to the metal center while the remaining substituent covalently links multiple chelating moieties together (for example DO3A, Fig. 2). The linking substituent is often designed with a donor atom such that eight donors are maintained and the kinetic stability of the chelate is minimally compromised [3]. This popular strategy was demonstrated in early contrast agent research by Tweedle and coworkers with the DO3A synthon [34].

Fig. 2.

Common chelates in multimeric ligands. Arrows point to positions where linking substituents can be attached.

Although macrocyclic chelates are the most popular motifs used in multilanthanide complexes, acyclic chelates offer a different set of structural variations. A common acyclic chelate motif is diethylenetriaminetetraacetic acid (DTTA) (Fig. 2). Multimeric ligands featuring this motif sometimes require sequential protection and deprotection steps to attach a linking moiety selectively [35]. The kinetic stability of the resulting lanthanide complexes is reduced relative to the parent DTPA complex when the linking moiety does not contain a donor atom, leaving the chelate with only seven metal-binding sites [35]. The reduced stability of seven-coordinate acyclic chelates has limited their use in multilanthanide complexes.

Of equal importance to chelate design is the choice of linking moieties to provide functionality. Linkers are used to determine the number of chelates, control metal-metal distance, rigidify the relative motion of metal ions, interact with analytes, and function as antennas for absorbance and energy transfer. Linker structure and function will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

CONTRAST AGENTS FOR MRI

The first application of multilanthanide systems that this review will describe is contrast agents for MRI, which is an important diagnostic technique for the medical field. Roughly 30% of images acquired in a clinical setting involve the administration of a contrast agent to increase the diagnostic information available from the images [2]. Contrast agents are paramagnetic substances that decrease the longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times of water protons, thereby increasing contrast in images. Detailed reviews of relaxation theory have been published [3, 36, 37]. With seven unpaired electrons, GdIII is highly paramagnetic and especially well suited for use as a T1-shortening contrast agent for MRI. However, GdIII is toxic as the free ion and, therefore, must be chelated in a kinetically inert ligand for use in vivo [38].

In addition to kinetic inertness, a variety of other parameters can be tuned by changing ligand structure. These parameters ultimately influence a measurable value of contrast-agent efficiency called relaxivity, which has units of mM−1s−1. According to the Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan (SBM) and Freed equations that describe the behavior of T1-shortening contrast agents, optimal relaxivity (r1) is achieved when the condition in Equation 1 is satisfied [2, 3].

| Equation 1 |

In Equation 1, ω1 is the proton Larmor frequency, 1/τR is the rotational correlation rate, 1/τm is the bound-water exchange rate, and 1/T1e is the electronic relaxation rate of GdIII. A common magnetic field strength for the study of multilanthanide complexes is 0.47 T, which corresponds to a proton Larmor frequency of 20 MHz, whereas a common clinical field strength is 1.5 T, which corresponds to a Larmor frequency of 64 MHz. While field strength influences relaxivity, the trends that we will elucidate from the studies of multilanthanide complexes are valid at clinical magnetic fields because at either field strength, the sum of 1/τR, 1/τm, and 1/T1e must be on the order of 107 s−1 to achieve maximum relaxivity. Additionally, as magnet technology improves and higher field strengths become available, optimal values of these three parameters will need to be achieved through ligand design. The need to tune the structure of contrast agents for MRI to reach specific values of the three parameters listed above has resulted in decades of studies of monometallic lanthanide chelates, and several detailed reviews have been published on this topic [39–41]. Due to the multitude of studies focused on the relationship between the structural features of lanthanide chelates and their corresponding ability to function as contrast agents, a functional understanding of the effects of molecular structure on 1/τR, 1/τm, and, to a lesser degree, 1/Tle has been developed. We will now discuss the relationships between these parameters and the structure of multilanthanide complexes.

ROTATIONAL CORRELATION RATE

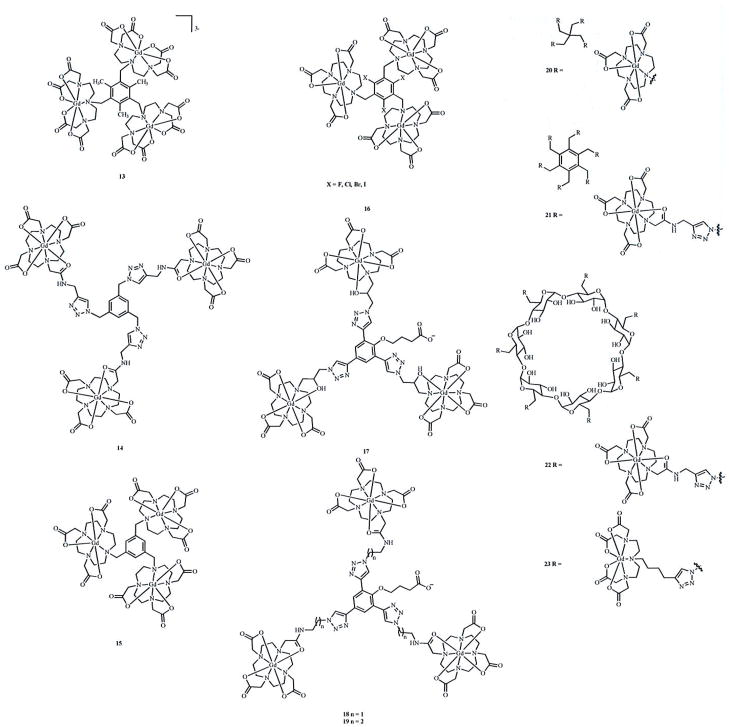

The rotational correlation rate, 1/τR, describes the rotation of the Gd-H vector. Therefore, both the global and local motions of chelates affect the magnitude of 1/τR. The local component of 1/τR has been referred to as 1/τ1O or 1/τR* and has been analyzed as a separate component from the global 1/τR with the Lipari-Sazbo method [35, 42, 43]. While higher molecular weights result in slower values of 1/τR for monometallic chelates, this relationship is essentially nonexistent for multilanthanide complexes of intermediate molecular weight such as those shown in Fig. (3a, b). Studies on the behavior of intermediate to high molecular weight compounds with multiple lanthanide chelates indicate that the local motion of one chelate relative to another limits the degree to which a high molecular weight can decrease 1/τR. An early study demonstrated the influence of local motion on 1/τR and relaxivity using a cyclic moiety to bridge two DO3A-type chelates (Fig. 4) [34]. Relative to the more flexible linker on complex 24, a slightly higher relaxivity was achieved with 25. However, inspection of molecular structure reveals that even the cyclic-linked structure retains some degree of freedom between chelates due to potential ring inversion suggesting that even more rigidity is needed in linker design.

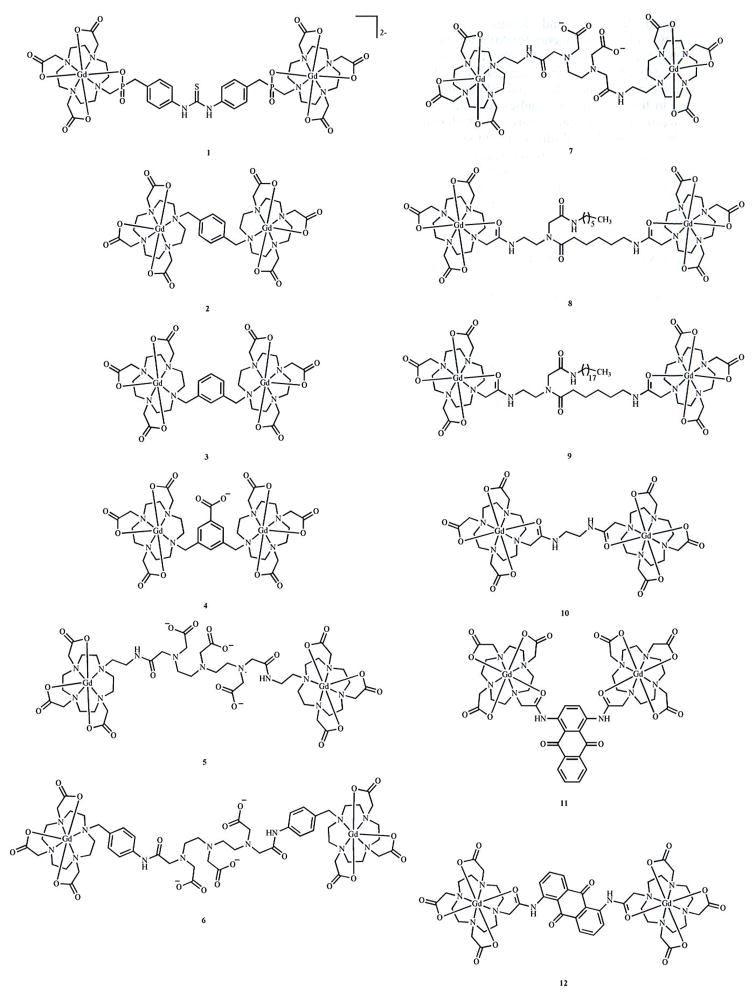

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3a. Multilanthanide complexes studied for use as contrast agents for MRI reported since 2006. Due to a lack of data necessary for comparison to other complexes described in this article, complex 10 is not discussed in the text [51]. Coordinated water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

Fig. 3b. Multilanthanide complexes studied for use as contrast agents for MRI reported since 2006. Due to a lack of relevant data, complexes 16 and 20 are not discussed in the text [52, 53]. Coordinated water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

Fig. 4.

Multilanthanide complexes with nonrigid (24) and rigid (25) linkages deviate from the MW-1/τR relationship observed in larger complexes.

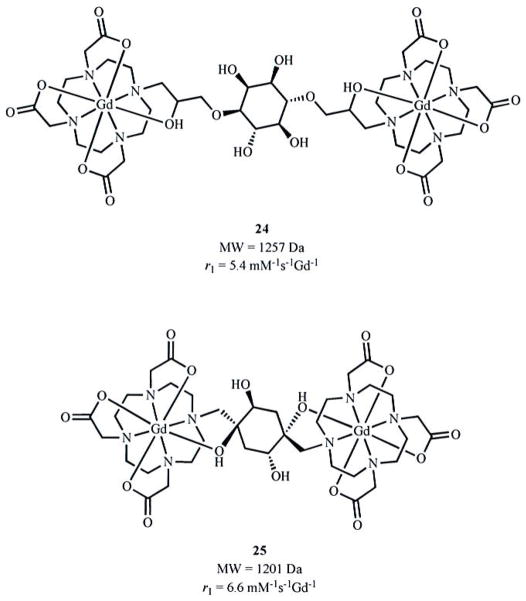

Analysis of recently reported dimetallic complexes also reveals that 1/τR is not strictly dependent on molecular weight. Of the 23 complexes presented in this review, only 14 were reported with 1/τR values calculated by fitting nuclear magnetic resonance dispersion (NMRD) data at 298 K. (Values of 1/τR determined using 17O-NMR spectroscopy cannot be directly compared to NMRD-derived values because the 17O-NMR technique assesses 1/τR of the Gd-O vector, which is different than 1/τR of the Gd-H vector that is assessed using NMRD data.) Plotting 1/τR for these complexes against molecular weight reveals no apparent relationship (Fig. 5) [35, 44–50]. The lack of a correlation between 1/τR and molecular weight may be due in part to the narrow molecular weight range (1100–6000 Da) of this class of compounds, but it is also attributable to the lack of a quantitative model to predict the degree to which the local motion of the chelates contributes to 1/τR. For instance, inspection of 2 and 3 suggests that steric repulsion between the chelates in 3 should restrict the local motion of the chelates relative to the chelates in 2 [45]. Therefore, 1/τR might be expected to be slower for 3 than 2 due to a slower 1/τR*. However, 1/τR is 36% slower for 2 than it is for 3. The reason behind this apparent disagreement may be that the hydrodynamic radius of 2 is slightly larger than that of 3 due to para- versus meta-substitution of the linker. In cases where the hydrodynamic radius can be regarded as similar, such as for 3 and 4, the molecular weight appears to correlate inversely with 1/τR.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of molecular weight to 1/τR for complexes 1–8, 11–13, 15, and 17. Values of 1/τR were determined by fitting NMRD data acquired at 298 K. The number at each point corresponds to the number of the complex shown in Fig. (3a, b).

Complexes 5–7 also show an inverse correlation between 1/τR and molecular weight [46]. In this case, 1/τR and relaxivity both follow the expected trends of decreasing and increasing, respectively, with increasing molecular weight. Although the authors refer to the rigidity of the structure of 6 relative to 5 as an explanation for its slower 1/τR and higher relaxivity, it is important to note that 6 also has the highest molecular weight of the three similar complexes [46]. The influence of molecular weight on 1/τR was not of particular interest to the study, which focused on CaII binding, but demonstrates the combined effect of rigidity and molecular weight on 1/τR in multimetallic species. The lessons learned from studying multilanthanide complexes indicate that the rigidity of macromolecular structure is paramount to achieving maximum relaxivity; however, in spite of a qualitative understanding of the value of 1/τR, 1/τR for new multilanthanide complexes is difficult to estimate. Further fundamental studies exploring the modulation of 1/τR and 1/τR* are necessary to enable rational improvements to the design of multilanthanide and macromolecular complexes as contrast agents for MRI. These improvements include the use of ultra-high-field magnets that generate higher resolution images in shorter scan times, properties that are likely to improve clinical diagnosis.

WATER-EXCHANGE RATE

Water-exchange-rate, 1/τm, is usually not the limiting factor in relaxivity for low to intermediate molecular weight contrast agents. However, 1/τm becomes limiting as magnetic field strength increases, and 1/τm will need to be modulated to generate effective contrast agents at ultra-high magnetic field strengths (≥7 T). Methods of modulating 1/τm include changing ligand basicity or changing the number of coordinating atoms [54–56]. More basic chelates decrease Lewis acidity of coordinated lanthanide ions, which in turn results in weaker water-lanthanide interactions and a concomitant increase in 1/τm. Also, complexes formed from heptacoordinate chelates typically exhibit a faster 1/τm than complexes formed with octadentate chelates, consistent with an associative water-exchange mechanism allowed by the second available coordination site. As a point of reference, 1/τm values for GdDOTA and GdDTPA are 4.1 × 106 s−1 and 3.3 × 106 s−1, respectively, an order of magnitude slower than optimal at 0.47 T and even less optimal at higher fields [57]. Therefore, a faster 1/τm is desirable regardless of field strength. Values of 1/τm are especially important for higher molecular weight complexes where 1/τR is near an optimal value and 1/τm begins to be the limiting factor in optimizing relaxivity.

The charge and denticity of a chelate are the primary structural features that affect 1/τm. As many synthetic strategies have centered upon DO3A- or DTTA-type chelating moieties, the charge of the ligand is typically only determined by the charges of the substituents on the cyclen or ethylene triamine backbone. Consequently, many multimeric ligands carry three acetate groups per GdIII ion to form neutral complexes.

An alternative method to increase 1/τm is to sterically crowd the water-binding site [54–56]. Designing a ligand that introduces steric interference without eliminating the coordinated water molecule is a challenging task. As a result, little research has been conducted with an aim to modulate water exchange in multilanthanide complexes, although several multilanthanide complexes exhibit a faster water exchange rate compared to their monometallic counterparts. For instance, 1 exhibits a nearly optimal 1/τm, value of 1.9 × 107 s−1 at 0.47 T where ω1 is 2.0 × 107 s−1 [44]. Complexes 3, 4, 7, and 15 have 1/τm, values roughly an order of magnitude closer to ω1 than GdDOTA [45, 46, 49]. The faster 1/τm for 3, 4, 7, and 15 can be attributed to the associative exchange mechanism induced by the heptacoordinate chelates and is probably not due to steric crowding. However, the steric effect of packing several chelates close together is evidenced by the hydration number, q, of these complexes. Rather than the expected q = 2, heptacoordinate chelates 3, 4, and 7 are monohydrated at each lanthanide [45, 46].

Conversely, complexes 8, 9, 11, and 12 have slower exchange rates than GdDOTA and GdDTPA which can be attributed to the substitution of an acetate with an amide attached to the linker [47, 48]. Therefore, the Lewis acidity of GdIII in these complexes is likely greater compared to tetra- or pentaacetate analogues, leading to stronger water-Gd interactions. However, the Lewis acidity of the GdIII ions is not the only factor affecting the water-exchange rates observed for multilanthanide complexes.

Complex 13 is a unique example of a multilanthanide complex that contains three DTTA-based chelates [35]. Surprisingly, the water-exchange rate for 13 (1/τm = 9.01 × 106 s−1) is three times slower than that of the DO3A-based analog, 15(1/τm = 32 × 106 s−1), even though the GdIII ions in 13 are less Lewis acidic than those in 15 [35, 49]. Further, 1/τm is slower in 13 than in 1, 3, 4, and 7, all of which are reported with q = 1 and would be expected, therefore, to exchange water more slowly [35, 44–46, 49]. It is not obvious what structural features cause this difference in water-exchange rates and, in particular, what causes the water-exchange rate of 13 to be slower than what we might expect relative to the DO3A-based 15. With this difference in mind, it would be intriguing to compare the water-exchange rates of the heptagadolinium β-cyclodextran-based 22 and 23 that presumably have high enough molecular weights that the water-exchange rates will contribute to relaxivity [58–60]. Complexes 22 and 23 differ in their chelates, and a comparison of their water-exchange rates would be useful to study the effect of chelate structure on relaxivity. However, 1/τm was not reported for these complexes.

In general, a challenge associated with directly studying water exchange in multilanthanide complexes is the complexity of synthesizing multimeric ligands. However, comparison of 1/τm to ωI at higher magnetic fields reveals that 1/τm may become limiting for many multilanthanide complexes [2, 3]. Further, the relaxivity of macromolecular systems with 1/τR approaching ωI will be limited by 1/τm indicating a need to optimize 1/τm in these larger systems; therefore, there is a need in contrast agent research to address 1/τm modulation in multilanthanide systems.

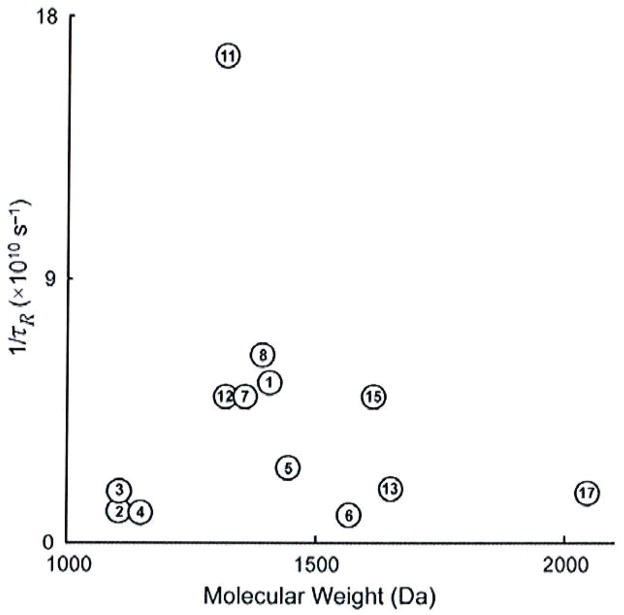

GdIII ELECTRONIC RELAXATION RATE

The potential of multilanthanide complexes to be used as contrast agents for MRI should be discussed noting that changes in electronic relaxation rate, 1/T1e, have been observed in multilanthanide complexes [61–63]. The electronic relaxation rate is typically estimated based on the zero field splitting parameter, Δ2, and the electronic-relaxation correlation time, τv [64]. Substituting the reported Δ2 and τv values for GdDOTA into Equation 2 [64], we calculated 1/T1e for field strengths from 0.5 T to 10 T and plotted these values and ωI versus field strength (Fig. 6). Equation 2 is considered to be valid only in the range where ωs2τv2 ≪ 1, where ωs is the electron Larmor frequency and S is the GdIII electron spin (S = 7/2) [64]. Therefore, these values are our best estimate due to the lack of empirical analysis of 1/T1e outside this range. Comparison of the two functions shows that 1/T1e is 750% faster than optimum at 1.5 T. While 1/T1e is an order of magnitude closer to ωI than 1/τR for the monometallic GdDOTA, 1/T1e and 1/τR are on the same order of magnitude (109 s−1) for several multilanthanide complexes. Of the complexes presented in this review, four have 1/T1e-Iimited relaxivity based on a comparison of 1/τR, 1/τm and 1/T1e values. It is likely that 1/T1e is also limiting for higher molecular weight complexes. While the need to understand and manipulate 1/T1e is apparent, studies of monometallic GdIII-containing complexes to determine structural features that influence electronic relaxation have been inconclusive. Interestingly, the study of multilanthanide complexes could contribute to the improvement of contrast agents through increasing our understanding of 1/T1e.

Fig. 6.

Plot of ωI (◆) and 1/T1e for GdDOTA (■) over the low to ultra-high magnetic field strength range. The gray bar represents the range of field strengths at which most multilanthanide complexes have been studied up to common clinical field strengths.

| Equation 2 |

Previous reports describing multilanthanide complexes have suggested a dipolar relaxation mechanism as an explanation for shorter 1/T1e values in multimetallic systems [62, 63]. However, if a dipolar relaxation mechanism is responsible for modulating 1/T1e in multilanthanide complexes, 1/T1e will likely depend on Gd-Gd distances and could be studied with a series of identical chelates and variable-length linkers. The results of these studies would enable the rational synthesis of systems with optimized 1/T1e to fulfill the condition in Equation 1. Currently, the design of macromolecular lanthanide-containing complexes for contrast agents is essentially limited to attempts to optimize 1/τR and 1/τm.

Although previous studies of dinuclear complexes 5–7 did not focus on electronic-relaxation rate [46], we made an effort to elucidate a relationship between the distance separating the chelates (estimated by the number of atoms between Gd ions) and 1/T1e (calculated from reported Δ2 and τv values and Equation 2). Our choice to compare only complexes 5–7 is based on the similarity in structure of the chelates and linkers. Other complexes were not considered part of the series due to the lack of structural similarity or published data. In complexes 5–7, 1/T1e decreases from complex 7 (16-atom-separation) to complex 5 (19-atom-separation) to complex 6 (24-atom separation) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the Distance Between GdIII Chelates to Calculated Electronic Relaxation Times at 0.47 T [46]

| Complex | Atom Separation | T1e (ps) |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 16 | 41.5 |

| 5 | 19 | 58.5 |

| 6 | 24 | 87.0 |

The purpose of this observation is not to make conclusions or a quantitative assessment of the data but to present the possibility that, with further study of multimetallic and in particular dimetallic lanthanide complexes, a method to modulate and understand 1/T1e could be developed. Currently, the absence of empirical data and direct experimental techniques to interrogate 1/T1e represents a challenging opportunity for exploration. Gaining a fundamental understanding of 1/T1e is necessary to improve contrast agents for current clinical fields and to understand how effective high-field contrast agents can be synthesized.

HYDRATION NUMBER

Another important factor in determining relaxivity is the hydration number of the lanthanide, q. According to the SBM equations, q scales directly with r1 [3]. As mentioned, the disadvantage of chelates with a hydration number greater than one (with a few exceptions [65]) is that these complexes tend to be kinetically labile and, therefore, toxic. Despite this limitation, researchers have synthesized multilanthanide complexes with linking moieties that do not contribute a coordinating atom, resulting in q = 2 chelates. This design has resulted in some of the highest relaxivity multilanthanide complexes such as 13 (r1 = 15.70 mM−1s−1Gd−1, 310 K, 0.47 T) [35]. However, these dihydrated metal ions will likely be limited to preclinical studies because of their labile nature.

PARACEST MRI

In the last decade, paramagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (PARACEST) agents have been developed for MRI [66–68]. A PARACEST agent is a molecule that has exchangeable protons (for example alcohols, amides and metal-bound water) that are shifted by a paramagnet. Paramagnetic substances such as lanthanide ions are able to shift some exchangeable protons 100 parts per million (ppm) or more [66–68]. Detailed reviews on the mechanism of PARACEST and lanthanide-based PARACEST agents are available [66–69]; therefore, we will only briefly describe the features of PARACEST agents that are relevant to multilanthanide systems.

PARACEST imaging relies on the exchange of one or more protons from a paramagnetic complex with protons from the bulk water. A PARACEST image is generated by subtracting two maps of bulk-water-peak intensity: a reference map acquired without a presaturation pulse and a map acquired after a presaturation pulse at the resonance frequency of the exchanging protons. The PARACEST image is the difference in bulk-water-peak-intensity between the reference and presaturated maps. Because the PARACEST phenomenon causes a decrease in bulk-water peak intensity, the scale of a PARACEST image represents the degree of bulk-water-peak suppression.

The efficiency of a PARACEST agent is determined by two factors: (1) the proton-exchange rate, kex, and (2) the difference between the exchanging-proton and bulk-water chemical shifts, Δω [66–69]. For a paramagnetic substance to effectively transfer saturated protons to the bulk water, kex should be less than or equal to |Δω| [66–69]. Therefore, greater differences in chemical shift (large Δω) allow for faster proton-exchange rates. PARACEST imaging is advantageous compared to T1- and T2-based MRI because there is no background signal in a PARACEST image. However, like other MR imaging techniques, PARACEST imaging is insensitive and requires a high concentration (mM) of agent to generate satisfactory images. Therefore, an agent with a large number of exchangeable protons is desirable for decreasing the concentration of agent required [70, 71].

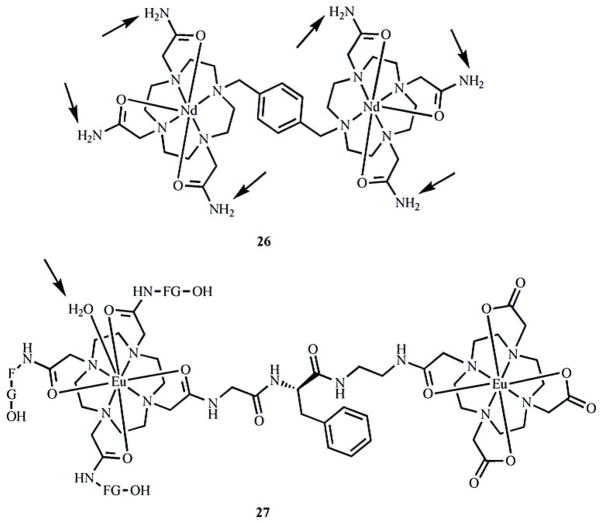

Of reported PARACEST agents, only two dimetallic lanthanide complexes fit the category of complexes described in this review. Complex 26 (Fig. 7) contains 12 amide protons with chemical shifts that are shifted 12 ppm from the bulk water peak [72]. Although this shift is small and partial overlap with the bulk water peak exists, a PARACEST effect was observed to reduce the bulk water signal by 30% for a 10 mM solution of complex 26 [72]. With complex 27, PARACEST is due to the exchange of coordinated and bulk water molecules (Fig. 7) [73]. The chemical shift of the coordinated water protons is shifted 45 ppm from the bulk water signal, and a 30% reduction in the bulk-water signal was observed for a 10 mM solution of complex 27 [73]. This result is similar to the PARACEST effect observed for a EuIIIDOTA tetra(amide) mononuclear analog [29], indicating that the effect is not augmented by the presence of the second chelate. A potentially more useful molecule may contain two covalently linked amide-based chelates and, therefore, double the number of exchanging water molecules. These preliminary successes of multilanthanide complexes as PARACEST agents provide proof-of-concept that this class of complexes can be used as PARACEST agents. Further exploration of ligands designed to have more highly shifted exchangeable proton peaks is an important direction of future research in this field. Additionally, water exchange in some multilanthanide complexes has been shown to be slower than their monometallic counterparts studied for T1-based MRI. Thus, we expect that these ligands could be useful for making PARACEST agents with lanthanides other than GdIII. The use of these multimeric ligands in PARACEST agents has not been reported, but the water-exchange rates reported for their GdIII complexes indicate that their complexes with other lanthanides could be useful as PARACEST contrast agents for MRI. Studies of multilanthanide systems will likely lead to an understanding of how a sufficient chemical shift of a large number of exchangeable protons can be achieved. This understanding has the potential to be applied to macromolecules that contain many exchangeable protons and, therefore, produce highly sensitive PARACEST contrast agents.

Fig. 7.

Multilanthanide PARACEST agents that contain exchangeable protons capable of reducing the bulk-water-signal intensity (arrows point to exchangeable protons). Water molecules not observable by PARACEST have been omitted for clarity.

MULTILANTHANIDE-BASED LUMINESCENT PROBES

While lanthanides other than GdIII are used in PARACEST imaging, they also lend themselves to optical imaging. Lanthanides exhibit luminescent behavior that results from 4f electronic transitions [74]. These transitions are Laporte forbidden and result in narrow, low intensity emission bands compared to organic fluorophores. The narrow line width of lanthanide emission peaks generates characteristic emission spectra that enable identification of lanthanide-based probes. Additionally, the lifetimes of lanthanide emissions can be on the order of micro- to milliseconds, much longer than organic molecules including biomolecules [74–79]. These exceptionally long luminescence lifetimes are the key advantage to lanthanide-based probes for medical applications [74–79]. Background autofluorescence from organic biomolecules decays much faster than lanthanide luminescence such that a delay between excitation and detection in an imaging experiment will eliminate non-lanthanide-based background fluorescence. The possibility that zero-background images could be acquired using luminescent lanthanide probes makes their study a worthwhile pursuit to the medical field. Luminescent lanthanide complexes that are responsive to medically relevant biochemical events could become useful diagnostic probes based on specific molecular-level interactions. Probes based on these interactions have the potential to improve the precision, accuracy, and ease-of-use of diagnostic assays. Further, use of kinetically inert complexes such as those discussed in this review might allow diagnoses in vivo.

Multilanthanide complexes with Eu and Tb have been studied due to their long luminescence lifetimes (110 to 400 μs) and their intense emission bands (relative to other lanthanides) in the visible region. For in vivo imaging emission in the visible region may be viewed as a limitation due to minimal tissue penetration of emitted wavelengths that require invasive detection methods. YbIII complexes emitting in the near-IR region have also been reported to address the issue of improving the tissue depth at which luminescence can be detected [80]. However, due to the similar coordination chemistry throughout the lanthanide series, the study of Eu and Tb complexes is necessary to determine many structural parameters and provide proof-of-concept for detecting a response. Other lanthanides are typically not strong emitters and have not been reported multilanthanide complexes for these applications, presumably for this reason.

LIGAND DESIGN

Although considerations to prevent lanthanide toxicity using polydentate chelates are necessary for luminescent probes, three other factors also must be considered for the design of multilanthanide complexes for luminescence-related applications. First, OH and NH oscillators are efficient quenchers of Ln luminescence; therefore, to preserve long Ln luminescent lifetimes, polydentate chelates must not contain OH or NH oscillators in the inner coordination sphere of the metal ion [75–77, 81]. Second, the low quantum efficiency of Ln ions can be improved with ligands containing organic fluorophores (antennas) that absorb and transfer energy to Ln excited states [75–77, 81, 82]. Third, without interactions with substrates, luminescent lanthanide complexes have little use in medicine; therefore, ideally, the emission intensity or wavelength will change upon the interaction of a substrate with the complex. Ln ions are strong Lewis acids and are capable of binding to a wide variety of anions; however, useful sensing applications require that binding be specific, which requires control of the Ln coordination sphere through judiciously designed ligands. Alternatively, a complex can be designed to bind to an analyte of interest and detection can take place after unbound complex has been washed or diffused away. This strategy has not been reported for multilanthanide systems and represents an unexplored area of future research.

The synthesis of multimeric ligands tends to be more challenging than the synthesis of monomeric ligands; however, the sensitivity of Ln luminescent probes can be increased by a simple additive effect when multiple Ln ions are present in one complex. Another possible advantage of multilanthanide complexes is Ln-sensitized luminescence [80]. In these systems, interactions at each lanthanide can be interrogated separately for ratiometric sensing, wherein the response of the probe can be determined without determining the concentration of the probe [83]. Further, some multilanthanide complexes are known to display different properties than their monometallic analogs such as a response to or cleavage of DNA and RNA for reasons that are not well understood [48, 83, 84]. Yet, while the study of interactions between multilanthanide luminescent probes and DNA is still in its infancy, this class of compounds has the potential to generate useful tools for gene sensing or for therapy in the medical field.

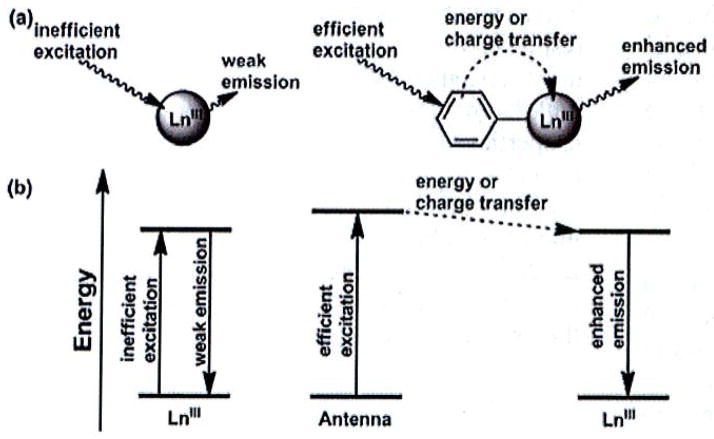

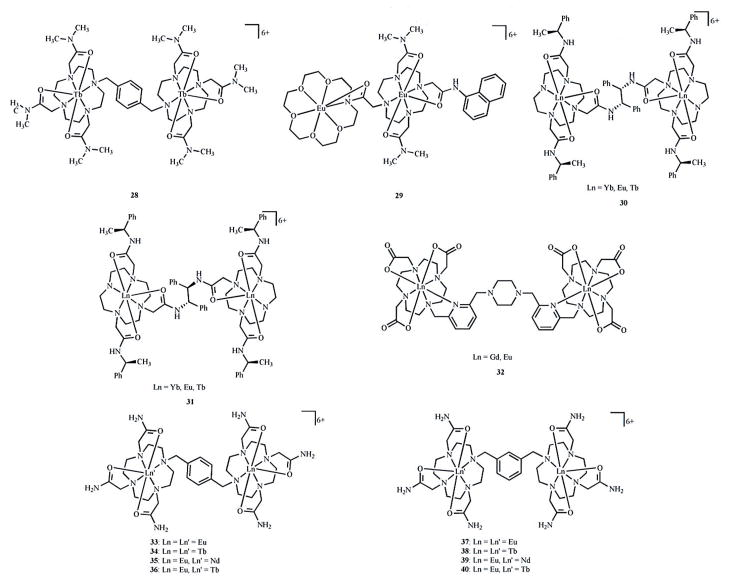

ANTENNAS

Ligands appended with organic fluorophores improve the quantum yield of lanthanide complexes. This improvement is due to more efficient excitation of the chromophore relative to direct excitation of the lanthanide, as illustrated in Fig. (8). The specific processes involved in the transfer of energy from the ligand excited state to the lanthanide excited state depend on the relative energies of the donor and acceptor states and detailed reviews of this phenomenon are available elsewhere [75, 77, 78, 81]. Nearly all multilanthanide complexes synthesized for medical sensing applications contain an antenna in the linker (Fig. 9). Complexes 28 and 30–40 contain aromatic groups that function as antennas within these linkers [83–87]. The efficiency of energy transfer depends in part on the Ln-antenna distance; therefore, antennas that coordinate to the Ln ion such as the pyridyl ligands in 32 are expected to better sensitize Ln emission than those that transfer energy through space. An additional requirement for the antenna is that the excited energy state must be higher than the Ln excited state and must be sufficiently higher in energy to prevent back energy transfer. Therefore, the antenna excited state should lie at least 1200 cm−1 above the emissive lanthanide excited state [88]. Many conjugated systems other than those shown in Fig. (9) could be used as antennas as long as the excited-state energy level of the antenna is matched to the lanthanide. Due to the wide variety of possible antenna-lanthanide combinations, the study of multilanthanide luminescent probes is expected to expand in the future. Another interesting observation in multilanthanide luminescent probes is that a single fluorophore is capable of sensitizing two Ln ions as demonstrated in complexes 28 and 33–40 [83–85]. The knowledge gained from studying how multiple lanthanide ions are sensitized by a single antenna is likely to indicate how macromolecular systems can be designed with multiple lanthanide ions excited by a single antenna. This type of design would be advantageous over multiple-antenna-containing systems by minimizing the complexity of the macromolecular structure.

Fig. 8.

(a) Illustration of the excitation and emission processes of a lanthanide ion by direct excitation (left) and antenna-sensitized excitations (right), (b) Simple Jablonski diagram of lanthanide excitation and emission processes during direct excitation (left) and antenna-sensitized excitation (right).

Fig. 9.

Multilanthanide complexes studied as luminescence probes discussed in this review. Coordinated water molecules have been omitted for clarity.

LUMINESCENCE SENSING

Adding functionality to multilanthanide complexes brings additional complexity to the design and synthesis of multimeric ligands. The majority of multilanthanide luminescent probes have been synthesized with tetraamide chelates (Fig. 9). Tetraamide chelates are strong Lewis acids that are potentially useful as anion sensors due to strong binding to negatively charged substrates relative to their neutral counterparts. Dimetallic lanthanide complexes are of particular interest because they have been reported to exhibit different anion-binding characteristics than their monometallic analogs [83, 84]. Sensing anions may be useful in determining ion concentrations, which can be indicators of metabolism and homeostasis in cells, and understanding cellular processes may facilitate identification of cellular abnormalities that could be used to understand and diagnose disease. For example, complexes 28–31 and 33–36 bind anions such as phosphates and dicarboxylates through Lewis acid-Lewis base interactions [83–85, 87, 89]. Alternatively, the sensing of cations, especially toxic species such as HgII, is of interest for determining contaminant levels in vivo and ex vivo. For this reason, complex 32 was studied, and it was found to show a change in luminescence in the presence of the HgII cation [86]. The luminescence response is due to the pyridyl groups that leave the Ln coordination sphere to bind to HgII [86]. Of all substrates that have been studied with multilanthanide complexes, perhaps the most intriguing and potentially useful to the medical field is DNA. Complex 39 was reported to show luminescence changes in the presence of DNA [83]. This exciting result indicates that the development of gene-specific medical assays may be possible. However, how the interaction with DNA is effected by the structural characteristics of complex 39 is not well understood. While further investigation of the interaction of DNA with 39 is underway, studies exploring DNA-binding with new multilanthanide complexes will be useful to elucidate the structural features that are responsible for the DNA interaction.

As mentioned, sensitizing multiple Ln ions using one fluorophore has been demonstrated [83–85]. While double Ln sensitization is fundamentally interesting, it could be especially useful with heterometallic complexes. Hetero-multimetallic complexes would be ideal for ratiometric sensing where one Ln emission remains constant while the others change in response to a substrate. Ratiometric sensing would eliminate the need to know the concentration of the probe, making in vivo analysis of substrates such as cations, anions, and DNA possible where the probe concentration is unknown.

CURRENT & FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

The study of multilanthanide complexes is a necessary endeavor in pursuit of advanced medical diagnostics. Substantial contributions have been made to the fields of MRI and luminescence imaging by studying multilanthanide complexes. Continued study of these complexes will facilitate our understanding of the fundamental relationship between chemical structure and imaging properties. This knowledge is needed to enable the rational design of larger (nanoscale) complexes for medical applications. These complexes will likely contribute to the field of medical imaging in the form of ultra-high field contrast agents for MRI, activatable probes for MRI, and luminescent in vivo molecular imaging for personalized medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institutes of Health (R00EB007129), the Elsa U. Pardee Foundation, and Wayne State University for financial support during the writing of this manuscript.

SYMBOLS

- 1/τlO

local rotational correlation rate

- 1/T1e

electronic relaxation rate

- 1/τm

water exchange rate

- 1/τR

rotational correlation rate

- 1/τR*

local rotational correlation rate

- Δ2

zero field splitting parameter

- Δω

chemical shift difference

- kd

dissociation rate

- kex

water exchange rate

- KGdL

Gd-ligand dissociation constant

- q

water-coordination number

- r1

relaxivity

- S

electronic spin sum

- T1

longitudinal relaxation time

- T1e

electronic relaxation time

- T2

transverse relaxation time

- τV

electronic-relaxation correlation time

- ωl

proton Larmor frequency

- ωs

electron Larmor frequency

UNITS

- cm−1

wave umber

- Da

dalton

- K

kelvin

- MHz

megahertz

- mM−1s−1

per millimolar per second

- mM−1s−1Gd−1

per millimolar per second per Gd

- nm

nanometer

- ppm

parts per million

- ps

picoseconds

- s−1

per second

- T

tesla

ABBREVIATIONS

- DTPA

Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

- DTTA

Diethylenetriaminetetraacetic acid

- DO3A

1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-triacetic acid

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid

- Ln

Lanthanide

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MW

Molecular weight

- NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- NMRD

Nuclear magnetic resonance dispersion

- PARACEST

Paramagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer

- SBM

Solomon-Bloembergen-Morgan

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Villaraza AJL, Bumb A, Brechbiel MW. Macromolecules, dendrimers, and nanomaterials in magnetic resonance imaging: the interplay between size, function, and pharmacokinetics. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2921–59. doi: 10.1021/cr900232t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The chemistry of contrast agents in medical magnetic resonance imaging: Merbach AE, Tóth É, editors. Chichester. England: Wiley; 2001.

- 3.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2293–352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet E, Juanes O, Rodriguez-Ubis JC. Supramolecularly organized lanthanide complexes for efficient metal excitation and luminescence as sensors in organic and biological applications. Curr Chcm Biol. 2007;1:11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Port M. Contrast agent encapsulating systems for CEST imaging. 2006032705,2006 WO.

- 6.Yang JJ, Liu Z-R. Contrast agents prepared from mutagenized metal ion-binding scaffold proteins. 2007009058,2007 WO.

- 7.Van Veggel FCJM, Prosser RS, Dong C. Lanthanide rich nanoparticles, and their investigative uses in MRI and related technologies. 20072575649. CA. 2007

- 8.Axelsson O, Cuthbertson A, Meijer A. Preparation of contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy consisting of a cyclic oligoamide core of 3 to 4 idential monomer units with 3 to 4 paramagnetic chelate side chains. 2007111514. WO. 2007

- 9.Kiessling LL, Raines RT, Allen MJ. Magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents synthesized using ring-opening metathesis polymerization. 2007131084. WO. 2007 doi: 10.1021/ja061383p. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Hovinen J. Lanthanide chelates and chelating agents containing triazolyl subunits. 2008025886. WO. 2008

- 11.Uvdal K. Compositions containing metal oxide nanoparticles and their use as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging. 2008096279. WO. 2008

- 12.Axelsson O, Uvdal K. Visualization of biological material by the use of coated contrast agents. 2008096280. WO. 2008

- 13.Moore DA. High relaxivity coordinatively unsaturated lanthanide complexes. 2008134289. WO. 2008

- 14.Grotjahn D, Weiner E. Bifunctional chelators for sequestering lanthanides in cancer treatment. 20080107606. US. 2008

- 15.Langereis S, Burdinski D, Bevers EM, Hackeng TM, Pikkemaat JA. CEST MRI contrast agents based on non-spherical erythrocyte ghosts. 2009060403. WO. 2009

- 16.Burdinski D, Langereis S, Pikkemaat JA. Nonspherical contrast agents for CEST MRI based on bulk magnetic susceptibility effect. 2009069051. WO. 2009

- 17.Yang JJ, Liu Z, Li S, Zhou Y, Jiang J, Xue S, Qiao J, Wei L. Contrast agents, methods for preparing contrast agents, and methods of imaging. 2009146099. WO. 2009

- 18.Meijer A, Axelsson O, Braathe A, Olsson A, Johansen JH, Wynn DG. Compounds comprising paramagnetic chelates arranged around a central core and their use in magneto resonance imaging and spectroscopy. 2009127715. WO. 2009

- 19.Langereis S, Keupp J, Gruell H, Burdinski D, Beelen D. Drug carrier providing MRI contrast enhancement. 2010029469. WO. 2010

- 20.Reineke T, Bryson J. Theranostic polycation beacons comprising oligoethyleneamine repeating units and lanthanide chelates. 2011006011. WO. 2011

- 21.Butlin NG, Raymond KN, Xu J, D’Aleo A. Preparation of macrocyclic hydroxypyridinonyl (HOPO)-containing chelators of lanthanides and thier conjugates as luminescent probes. 2011025790. WO. 2011

- 22.Gunnlaugsson T, Leonard JP. Responsive lanthanide luminescent cyclen complexes: From switching/sensing to supramolecular architectures. Chem Commun. 2005:3114–31. doi: 10.1039/b418196d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langereis S, Dirksen A, Hackeng TM, van Genderen MHP, Meijer EW. Dendrimers and magnetic resonance imaging. New J Chem. 2007;31:1152–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menjoge AR, Kannan RM, Tomalia DA. Dendrimer-based drug and imaging conjugates: Design considerations for nanomedical applications. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:171–85. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rocha J, Carlos LD, Paz FAA, Ananias D. Luminescent multifunctional lanthanide-based metal-organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:92640. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00130a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan GP, Ai CW, Li L, Zong RF, Liu F. Dendrimers as carriers for contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging. Chin Sci Bull. 2010;55:3085–93. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu G, Yamashita M, Tian M, et al. The development of dendritic Gd-DTPA complexes for MRI contrast agents. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2010;6:42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A. Chemistry of the elements. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suchý M, Hudson RHE. Synthetic strategies toward N-functionalized cyclens. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:4847–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang S, Winter P, Wu K, Sherry AD. A novel europium(III)-based MRI contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1517–8. doi: 10.1021/ja005820q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green KN, Viswanathan S, Rojas-Quijano FA, Kovacs Z, Sherry AD. Europium(III) DOTA-derivatives having ketone donor pendant arms display dramatically slower water exchange. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1648–55. doi: 10.1021/ic101856d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrow JR, Aileen Chin KO. Synthesis and dynamic properties of kinetically inert lanthanide compounds: lanthanum(III) and europium(III) complexes of l,4,7,10-tetrakis(2-hydroxyethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:3357–61. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kotkova Z, Pereira GA, Djanashvili K, et al. Lanthanide(III) complexes of phosphorus acid analogues of H4DOTA as model compounds for the evaluation of the second-sphere hydration. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2009:119–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ranganathan RS, Fernandez ME, Rang SI, et al. New multimeric magnetic resonance imaging agents. Invest Radiol. 1998;33:779–97. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199811000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livramento JB, Helm L, Sour A, O’Neil C, Merbach AE, Tóth É. A benzene-core trinuclear GdIII complex: Towards the optimization of relaxivity for MRI contrast agent applications at high magnetic field. Dalton Trans. 2008:1195–202. doi: 10.1039/b717390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kowalewski J, Nordenskiöld L, Benetis N, Westlund P-O. Theory of nuclear spin relaxation in paramagnetic systems in solution. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 1985;17:141–85. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lauffer RB. Paramagnetic metal complexes as water proton relaxation agents for NMR imaging: Theory and design. Chem Rev. 1987;87:901–27. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cacheris WP, Quay SC, Rocklage SM. The relationship between thermodynamics and the toxicity of gadolinium complexes. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:467–81. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caravan P. Strategies for increasing the sensitivity of gadolinium based MRI contrast agents. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:512–23. doi: 10.1039/b510982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terreno E, Castelli DD, Viale A, Aime S. Challenges for molecular magnetic resonance imaging. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3019–42. doi: 10.1021/cr100025t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Datta A, Raymond KN. Gd-hydroxypyridinone (HOPO)-based high-relaxivity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:938–47. doi: 10.1021/ar800250h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrec M, Montelione GT, Levy RM. Estimation of dynamic parameters from NMR relaxation data using the Lipari-Szabo model-free approach and Bayesian statistical methods. J Magn Reson. 1999;139:408–21. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunand FA, Toth Ė, Hollister R, Merbach AE. Lipari-Szabo approach as a tool for the analysis of macromolecular gadoliniiim(III)-based MRI contrast agents illustrated by the [Gd(EGTA-BA-CH2)|2]nn+ polymer. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:247–55. doi: 10.1007/s007750000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rudovský J, Botta M, Hermann P, Koridze A, Aime S. Relaxometric and solution NMR structural studies on ditopic lanthanide(III) complexes of a phosphinate analogue of DOTA with a fast rate of water exchange. Dalton Trans. 2006:2323–33. doi: 10.1039/b518147j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costa J, Balogh E, Turcry V, Tripier R, Le Baccon M, Chuburu F, et al. Unexpected aggregation of neutral, xylene-cored dinuclear GdIII chelates in aqueous solution. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:6841–51. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mishra A, Fousková P, Angelovski G, et al. Facile synthesis and relaxation properties of novel bispolyazamacrocyclic Gd3+ complexes: an attempt towards calcium-sensitive MRI contrast agents. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:1370–81. doi: 10.1021/ic7017456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tei L, Gugliotta G, Avedano S, Giovenzana GB, Botta M. Application of the Ugi four-component reaction to the synthesis of ditopic bifunctional chelating agents. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:4406–14. doi: 10.1039/b907932g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones JE, Amoroso AJ, Dorin IM, et al. Bimodal, dimetallic lanthanide complexes that bind to DNA: the nature of binding and its influence on water relaxivity. Chem Commun. 2011;47:3374–6. doi: 10.1039/c1cc00111f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mieville P, Jaccard H, Reviriego F, Tripier R, Helm L. Synthesis, complexation and NMR relaxation properties of Gd3+ complexes of Mcs(DO3A)3. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:4260–7. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01597k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mastarone DJ, Harrison VSR, Eckermann AL, Parigi G, Luchinat C, Meade TJ. A modular system for the synthesis of multiplexed magnetic resonance probes. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5329–37. doi: 10.1021/ja1099616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanwar J, Datta A, Tiwari AK, et al. Facile synthesis of non-ionic dimeric molecular resonance imaging contrast agent: its relaxation and luminescence studies. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:3346–51. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01370f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jebasingh B, Alexander V. Synthesis and relaxivity studies of a tetranuclear gadolinium(III) complex of DO3A as a contrast-enhancing agent for MRI. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:9434–43. doi: 10.1021/ic050743r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Platzek J, Schirmer H, Weinmann H–J, Martin JL, Harto JR. Trimeric, macrocyclically substituted halo-benzene derivatives. 20060154989. US. 2006

- 54.Rudovský J, Kotek J, Hermann P, Lukeš I, Mainero V, Aime S. Synthesis of a bifunctional monophosphinic acid DOTA analogue ligand and its lanthanide(III) complexes. A gadolinium(III) complex endowed with an optimal water exchange rate for MRI applications. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:112–7. doi: 10.1039/b410103k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jászberényi Z, Sour A, Tóth É, Benmelouka M, Merbach AE. Fine-tuning water exchange on GdIII poly(amino carboxylates) by modulation of steric crowding. Dalton Trans. 2005:2713–9. doi: 10.1039/b506702b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mato-Iglesias M, Platas-lglesias C, Djanashvili K, et al. The highest water exchange rate ever measured for a Gd(III) chelate. Chem Commun. 2005:4729–31. doi: 10.1039/b508180g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helm L. Optimization of gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents for high magnetic-field applications. Future Med Chem. 2010;2:385–96. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bryson JM, Chu W-J, Lee J-H, Reineke TM. A b-cyclodextrin “click cluster” decorated with seven paramagnetic chelates containing two water exchange sites. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:150–59. doi: 10.1021/bc800200q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song Y, Kohlmeir EK, Meade TJ. Synthesis of multimeric MR contrast agents for cellular imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6662–3. doi: 10.1021/ja0777990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song Y, Meade TJ, Kohlmeir E. MRI contrast agents and related methods of use. 20090196829. US. 2009

- 61.Nicolle GM, Yerly F, Imbert D, Böttger U, Bünzli J-C, Merbach AE. Towards binuclear polyaminocarboxylate MRI contrast agents? Spectroscopic and MD study of the peculiar aqueous behavior of the LnIII chelates of OHEC (Ln=Eu, Gd, and Tb): implications for relaxivity. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:5453–67. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Powell DH, Dhubhghaill OMN, Pubanz D, et al. Structural and dynamic parameters obtained from 17O NMR, EPR, and NMRD studies of monomeric and dimeric Gd3+ complexes of interest in magnetic resonance imaging: an integrated and theoretically self-consistent approach. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9333–46. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tóth É, Helm L, Merbach AE, Hedinger R, Hegetschweiler K, Janossy A. Structure and dynamics of a trinuclear gadolinium(III) complex: the effect of intramolecular electron spin relaxation on its proton relaxivity. Inorg Chem. 1998;37:4104–13. doi: 10.1021/ic980146n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLachlan AD. Line widths of electron resonance spectra in solution. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1964;280:271–88. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Werner EJ, Kozhukh J, Botta M, et al. 1,2-Hydroxypyridonate/terephthalamide complexes of gadolinium(III): Synthesis, stability, relaxivity, and water exchange properties. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:277–86. doi: 10.1021/ic801730u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang S, Merritt M, Woessner DE, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. PARACEST agents: modulating MRI contrast via water proton exchange. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:783–90. doi: 10.1021/ar020228m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ali MM, Liu G, Shah T, Flask CA, Paget MD. Using two chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents for molecular imaging studies. Acc Chem Rev. 2009;42:915–24. doi: 10.1021/ar8002738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hancu I, Dixon WT, Woods M, Vinogradov E, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. CEST and PARACEST MR contrast agents. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:910–23. doi: 10.3109/02841851.2010.502126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pikkemaat JA, Wegh RT, Lamerichs R, et al. Dendritic PARACEST contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Contrast Media Mol I. 2007;2:229–39. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu Y, Zhou Y, Ouari O, et al. Polymeric PARACEST agents for enhancing MRI contrast sensitivity. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13854–5. doi: 10.1021/ja805775u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nwe K, Andolina CM, Huang C-H, Morrow JR. PARACEST properties of a dinuclear neodymium(III) complex bound to DNA or carbonate. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1375–82. doi: 10.1021/bc900146z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suchý M, Li AX, Bartha R, Hudson RHE. A bifunctional chelator featuring the DOTAM-Gly-L-Phe-OH structural subunit: en route toward homo-and heterobimetallic lanthanide (III) complexes as PARACEST MRI contrast agents. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:1087–90. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Horrocks WD, Jr, Sudnick DR. Lanthanide ion luminescence probes of the structure of biological macromolecules. Acc Chem Res. 1981;14:384–92. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Werts MHV. Making sense of lanthanide luminescence. Sci Prog. 2005;88:101–31. doi: 10.3184/003685005783238435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Choppin GR, Peterman DR. Applications of lanthanide luminescence spectroscopy to solution studies of coordination chemistry. Coord Chem Rev. 1998;174:283–99. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lis S. Analytical applications of lanthanide luminescence in solution. Chem Anal. 1993;38:443–54. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dickson EFG, Poollak A, Diamandis EP. Time-resolved detection of lanthanide luminescence for ultrasensitive bioanalytical assays. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1995;27:3–19. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(94)07086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yuan J, Wang G. Lanthanide-based luminescence probes and time-resolved luminescence bioassays. Trends Anal Chem. 2006;25:490–500. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Faulkner S, Pope SJ. Lanthanide-sensitized lanthanide luminescence: terbium-sensitized ytterbium luminescence in a trinuclear complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10526–7. doi: 10.1021/ja035634v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bünzli J-CG, Chauvin A-S, Kim HK, Deiters E, Eliseeva SV. Lanthanide luminescence efficiency in eight-and nine-coordinate complexes: role of the radiative lifetime. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:2623–33. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moore EG, Samuel APS, Raymond KN. From antenna to assay: lessons learned in lanthanide luminescence. Ac Chem Res. 2009;42:542–52. doi: 10.1021/ar800211j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andolina CM, Morrow JR. Luminescence resonance energy transfer in heterodinuclear LnIII complexes for sensing biologically relevant anions. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2011:154–64. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nwe K, Andolina CM, Morrow JR. Tethered dinuclear europium(III) macrocyclic catalysts for the cleavage of RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14861–71. doi: 10.1021/ja8037799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harte AJ, Jensen P, Plush SE, Kruger PE, Gunnlaugsson T. A dinuclear lanthanide complex for the recognition of bis(carboxylates): Formation of terbium(III) luminescent self-assembly ternary complexes in aqueous solution. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:9465–74. doi: 10.1021/ic0614418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Andrews M, Amoroso AJ, Harding LP, Pope SJA. Responsive, di-metallic lanthanide complexes of a piperazine-bridged bis-macrocyclic ligand: Modulation of visible luminescence and proton relaxivity. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:3407–11. doi: 10.1039/b923988j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Murray BS, Parker D, dos Santos CMG, Peacock RD. Synthesis, chirality and complexation phenomena of two diastereoisomeric dinuclear lanthanide(III) complexes. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2010:2663–72. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shiraishi Y, Furubayashi Y, Nishimura G, Hirai T. Sensitized luminescence properties of dinuclear lanthanide macrocyclic complexes bearing a benzophenone antenna. J I umin. 2007;127:623–32. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Plush SE, Gunnlaugsson T. Luminescent sensing of dicarboxylates in water by a bismacrocyclic dinuclear Eu(III) conjugate. Org Lett. 2007;9:1919–22. doi: 10.1021/ol070339r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]