Abstract

Background: Cause-of-death statistics is widely used to monitor the health of a population. African immigrants have, in several European studies, shown to be at an increased risk of maternal death, but few studies have investigated cause-specific mortality rates in female immigrants. Methods: In this national study, based on the Swedish Cause of Death Register, we studied 27 957 women of reproductive age (aged 15–49 years) who died between 1988 and 2007. Age-standardized mortality rates per 100 000 person years and relative risks for death and underlying causes of death, grouped according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, were calculated and compared between women born in Sweden and in low-, middle- and high-income countries. Results: The total age-standardized mortality rate per 100 000 person years was significantly higher for women born in low-income (84.4) and high-income countries (83.7), but lower for women born in middle-income countries (57.5), as compared with Swedish-born women (68.1). The relative risk of dying from infectious disease was 15.0 (95% confidence interval 10.8–20.7) and diseases related to pregnancy was 6.6 (95% confidence interval 2.6–16.5) for women born in low-income countries, as compared to Swedish-born women. Conclusions: Women born in low-income countries are at the highest risk of dying during reproductive age in Sweden, with the largest discrepancy in mortality rates seen for infectious diseases and diseases related to pregnancy, a cause of death pattern similar to the one in their countries of birth. The World Bank classification of economies may be a useful tool in migration research.

Introduction

Substantial inequalities in mortality between ethnic groups have been found in several countries.1–3 The mortality risk of immigrant populations may be higher or lower than the native population and can vary greatly by cause of death, cause of migration, origin, sex and age.4–8 Few studies have investigated cause-specific mortality rates in female immigrants.4–6,8 To reduce excess mortality, one needs to understand the factors causing the differences in risks. Cause-of-death statistics are widely used to monitor the health of the general population or specific groups of the population. Therefore, studies on causes of death are important for health planning and setting priorities to disease prevention. Women of reproductive age are exposed to the risk of pregnancy complications, which globally account for 14% of deaths in this age group.9 Studies from the UK, France and The Netherlands indicate that maternal mortality rates have tended to increase, whereby immigrants, especially Africans, have been shown to have a higher risk of maternal mortality.10–12 However, it has not always been possible to establish a causal link by adjusting for obstetric or well-known social risk factors.

Sweden today is a multi-ethnic society, having a higher proportion of foreign-born inhabitants than Great Britain or the USA.13 In 2007, 17% of all women of reproductive age in Sweden were foreign born.14 After the culmination of the labour immigration of the 1950s and 1960s, new waves of refugees from conflict zones in non-European countries began to arrive.4,13 As do all people, migrants carry with them ‘footprints’ of the socio-economic environments of their countries of origin. As Gross National Income (GNI) has been shown to be a major socio-economic determinant of population health,15,16 we hypothesized that women from poor countries would continue to be the most vulnerable group with regard to mortality after migration. The aim of this study was to analyse the causes of death in women of reproductive age to seek a correlation between the underlying cause of death and the economic situation of the individual’s country of birth—something that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been investigated before.

Methods

This is a national register study based on 27 957 deaths of women of reproductive age (defined by the World Health Organization as 15–49 years old) between 1988 and 2007. These individuals were identified through the Swedish Cause of Death Register (CDR), a record maintained by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare that includes all residents, whether or not the person in question was a citizen or was present in Sweden at the time of death. However, undocumented migrants and those who died while seeking asylum or visiting Sweden are not included. The register is based on death certificates issued by an attending physician or a physician conducting an autopsy. Variables obtained from the register included age, year of death, underlying cause of death and country of birth.

The underlying cause of death is defined as the disease or injury that initiated the pathological chain resulting in death or the circumstances surrounding the accident or act of violence that caused a lethal injury. Underlying and contributory causes of death are coded according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision17 (ICD-10) in the CDR. ICD-10 has been in use since 1997, preceded from 1987 to 1996 by ICD-9. In our study, we only considered the underlying cause of death (not contributory causes of death). The main chapters of the ICD-10 classification were used for grouping cases. Less common underlying causes of death were consolidated as ‘other diseases’ (ICD-10 chapters III, IV, VI–VIII, X–XIV, XVI–XVIII, XXI and XXII). When a death is due to injury, poisoning or other external factors (chapter XIX), the underlying cause of death is always the external cause (chapter XX). Suicide is classified as an external cause of death. Use of psychoactive substances, however, is classified as a mental and behavioural disorder, although some deaths from substance abuse could be classified as alcohol poisoning or drug overdose and thus within the chapter of external causes of death. Most changes in classification from ICD-9 to ICD-10 are not relevant to this study, with two exceptions: (i) ICD-10 reclassified human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) from ‘other metabolic disorders and immunity disorders’ to ‘certain infectious and parasitic diseases’. Thus, cases with an HIV/AIDS diagnosis in ICD-9 (n = 70) were moved to the group for infectious diseases. (ii) Cases of viral pneumonia in ICD-9 (n = 4) were also moved from ‘respiratory diseases’ in ICD-9 to the group for infectious diseases.

In contrast to studies from the UK and USA, in which self-selected ethnic group or race is commonly used for defining the population, we used the definition of an immigrant as a person who was born in one country and has moved to Sweden, irrespective of age, year or cause of migration. The countries of birth are linked to the CDR from the Swedish population register by means of each resident’s personal identification number. The deceased women were grouped by country of birth according to the World Bank country classification of 2007 (table 1). This classification is based on the GNI and revised every year.18 GNI is defined as the total value produced within a country (i.e. its gross domestic product) plus income received from other countries (interest and dividends), less similar payments made to other countries. In 2007, low-income countries were defined as having a GNI per capita of <936 USD, middle-income countries (often divided into lower and upper middle income) 936–11 455 USD and high-income countries >11 455 USD. Our study population included 27 952 women born between 1939 and 1992 (excluding five women because of unknown countries of birth).

Table 1.

Countries of birth of women of reproductive age who died in Sweden 1988–2007, grouped according to the Word Bank classification of economies for 200718

| Low-income countries |

| Afghanistan |

| Bangladesh |

| Burkina Faso |

| Burundi |

| Cambodia |

| Congo, Democratic Republic |

| Cote d'Ivoire |

| Eritrea |

| Ethiopia |

| The Gambia |

| Ghana |

| Kenya |

| Lao, People's Democratic Republic |

| Liberia |

| Madagascar |

| Mozambique |

| Nepal |

| Nigeria |

| Pakistan |

| Papua New Guinea |

| Sierra Leone |

| Somalia |

| Tanzania |

| Uganda |

| Uzbekistan |

| Vietnam |

| Yemen, Republic |

| Zambia |

| Middle-income countries |

| Algeria |

| Angola |

| Argentina |

| Azerbaijan |

| Barbados |

| Bolivia |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Botswana |

| Brazil |

| Bulgaria |

| Cameroon |

| Cape Verde |

| Chile |

| China |

| Colombia |

| Congo, Republic |

| Costa Rica |

| Croatia |

| Cuba |

| Czech Republic |

| Ecuador |

| Egypt, Arab Republic |

| El Salvador |

| Estonia |

| Georgia |

| Guyana |

| Honduras |

| India |

| Indonesia |

| Iran, Islamic Republic |

| Iraq |

| Jamaica |

| Jordan |

| Kazakhstan |

| Latvia |

| Lebanon |

| Libya |

| Lithuania |

| Macedonia, Former Yugoslav Republic |

| Malaysia |

| Mauritius |

| Mexico |

| Moldova |

| Morocco |

| Paraguay |

| Peru |

| Philippines |

| Poland |

| Romania |

| Russian Federation |

| Serbia and Montenegro |

| Soviet Uniona |

| South Africa |

| Sri Lanka |

| Sudan |

| Swaziland |

| Syrian Arab Republic |

| Thailand |

| Trinidad and Tobago |

| Tunisia |

| Turkey |

| Turkmenistan |

| Ukraine |

| Uruguay |

| Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic |

| West Bank and Gaza |

| Yugoslaviaa |

| High-income countries |

| Australia |

| Austria |

| Belgium |

| Canada |

| Denmark |

| Finland |

| France |

| Germany |

| Greece |

| Hong Kong, China |

| Hungary |

| Iceland |

| Ireland |

| Israel |

| Italy |

| Japan |

| Korea, Republic |

| Kuwait |

| Luxembourg |

| Macao, China |

| The Netherlands |

| New Zealand |

| Norway |

| Portugal |

| Singapore |

| Spain |

| Sweden |

| Switzerland |

| UK |

| USA |

a: Yugoslavia and Soviet Union were classified as middle-income countries.

For calculating the population at risk, we obtained data from the national repository of population records, Statistics Sweden. The estimated mid-year population of women 15–49 years old was calculated as the mean of the population on 31 December of a given year and the preceding year during the study period, divided into 5-years age groups and by countries of birth. Mortality risks per 100 000 person years were calculated using denominator data from the mid-year population. Age-standardized mortality rates were calculated with the Swedish-born women as a standard, as well as relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), in comparison with the Swedish-born group using Poisson regression. The analysis was performed with SAS version 9.2 and SAS Enterprise Guide 4.2 software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Among the 27 952 deceased women surveyed, 23 773 (85%) had been born in Sweden, 300 (1%) in low-income countries, 1 698 (6%) in middle-income countries and 2 181 (8%) in high-income countries other than Sweden. Women from the Nordic countries constituted 44% of the deceased immigrants (81% of those born in high-income countries), followed by women from the former Yugoslavia (10%), Poland (7%), Turkey (3%) and Iran (3%). In the group of women born in low-income countries, a majority (76%) came from African countries.

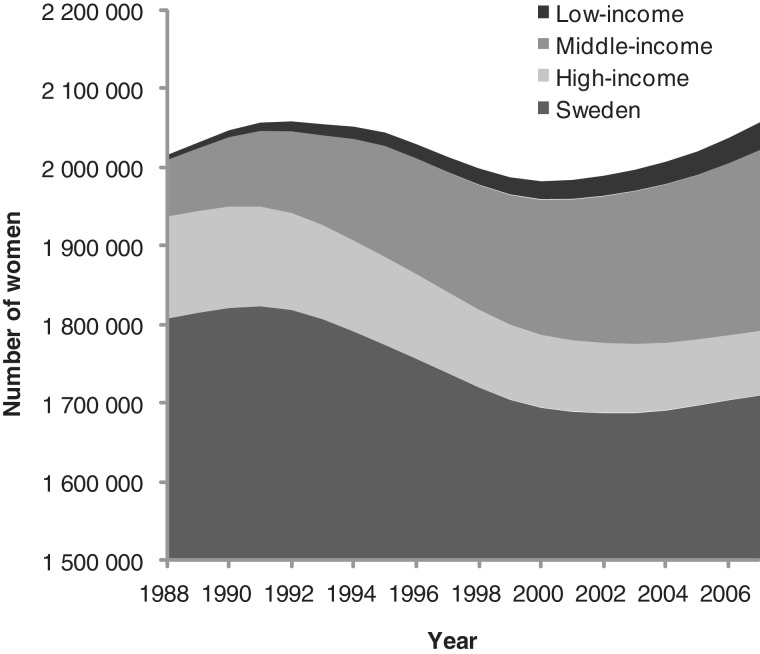

The proportion of foreign-born women in the total Swedish population increased during the study period, as shown in figure 1. The most common high-income countries of birth among the immigrants were Finland, Norway, Denmark, Germany and South Korea. The former Yugoslavia, Poland, Iran, Iraq and Turkey were the most common middle-income countries, and Ethiopia, Somalia, Vietnam, Afghanistan and Pakistan were the most common low-income countries of birth in the background population.

Figure 1.

Composition of Swedish female population of reproductive age, 1988–2007, by country of birth (please, note that the y-axis begins at 1 500 000)

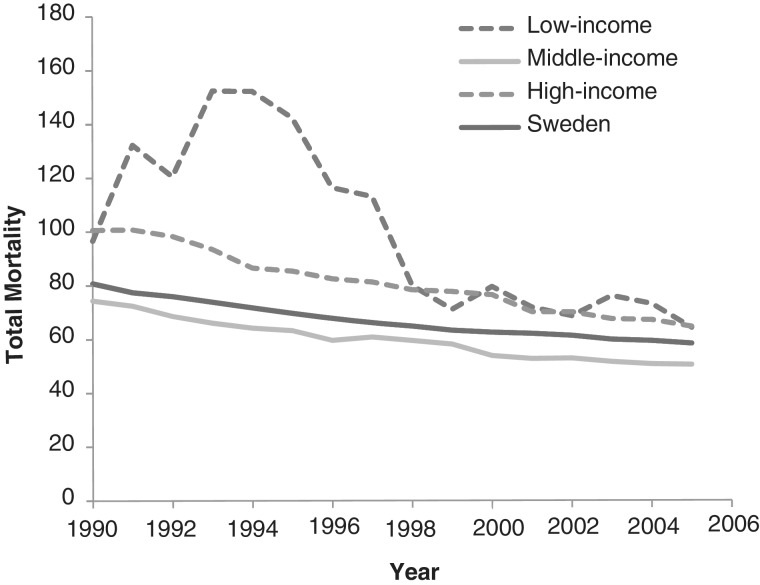

During the study period, total mortality decreased in all groups (figure 2). However, mortality for this period was significantly higher among women born in low- and high-income countries (standardized mortality rate = 84.4/100 000 and 83.7/100 000 person years, respectively) and lower in women born in middle-income countries (57.5/100 000), as compared with Swedish-born women (68.1/100 000) (table 2). The most frequent cause of death in all groups was neoplasm, followed by external causes. Among those external causes, suicide was the most common precipitating factor (47%), followed by traffic accidents (21%).

Figure 2.

Total age-standardized mortality per 100 000 person years during the study period (1988–2007), sliding mean values shown (5 years) for women born in low-, middle- and high-income countries and Sweden

Table 2.

Mortality rates and RR for women of reproductive age born in low-, middle- and high-income countries and Sweden, grouped by underlying cause of death

| Cause of Death | Sweden | Low income | Middle income | High income | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All causes | |||||

| Number of deaths | 23 773 | 300 | 1698 | 2181 | 27 952 |

| Mortality rate | 68.1 | 84.4 | 57.5 | 83.7 | 69.1 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 1.2 (1.2–1.3) | |

| Infectious/parasitic diseases | |||||

| Number of deaths | 297 | 43 | 37 | 30 | 407 |

| Mortality rate | 0.9 | 11.0 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 15.0 (10.8–20.7) | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | |

| HIV | |||||

| Number of deaths | 65 | 28 | 16 | 13 | 122 |

| Mortality rate | 0.2 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 39.2 (24.8–61.9) | 2.7 (1.6–4.7) | 2.7 (1.5–4.9) | |

| Infections, excluding HIV | |||||

| Number of deaths | 232 | 15 | 21 | 17 | 285 |

| Mortality rate | 0.7 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 7.1 (4.2–12.0) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | |

| Neoplasms | |||||

| Number of deaths | 9767 | 96 | 778 | 801 | 11 442 |

| Mortality rate | 28.0 | 31.9 | 26.6 | 28.5 | 28.3 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | |

| Mental and behavioural disorders | |||||

| Number of deaths | 495 | 1 | 13 | 92 | 601 |

| Mortality rate | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 0.2 (0.0–1.8) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | |||||

| Number of deaths | 2844 | 30 | 163 | 266 | 3303 |

| Mortality rate | 8.1 | 9.6 | 5.6 | 9.6 | 8.2 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | |

| Pregnancy and childbirth | |||||

| Number of deaths | 61 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 75 |

| Mortality rate | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 6.6 (2.6–16.5) | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 0.8 (0.2–2.5) | |

| Other diseasesb | |||||

| Number of deaths | 3876 | 49 | 211 | 340 | 4476 |

| Mortality rate | 11.1 | 12.4 | 7.1 | 12.9 | 11.1 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | |

| Accidents | |||||

| Number of deaths | 2303 | 20 | 135 | 176 | 2634 |

| Mortality rate | 6.6 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 7.5 | 6.5 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | |

| Suicides | |||||

| Number of deaths | 2989 | 34 | 221 | 319 | 3563 |

| Mortality rate | 8.6 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 14.0 | 8.8 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | |

| Other external causes | |||||

| Number of deaths | 1141 | 22 | 134 | 154 | 1451 |

| Mortality rate | 3.3 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 3.6 |

| RR (95% CI) | 1 a | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) |

Mortality rate = age-standardized mortality rate per 100 000 person years

a: Comparison group.

b: Other diseases include ICD-10 chapters III, IV, VI–VIII, X–XIV, XVI–XVIII, XXI and XXII.

The largest difference in mortality rates was seen among women who died of infectious diseases. HIV/AIDS was the most common of these as a cause of death among women from low-income countries (65%; RR: 39.2, 95% CI 24.8–61.9), but the risk was also high for other infectious diseases (RR: 7.1, 95% CI 4.2–12.0). Total mortality was still significantly higher among women born in low-income countries (RR: 1.4, 95% CI 1.2–1.5), but remained unchanged in other groups when HIV/AIDS was excluded from the data set. The risk of dying from diseases or complications related to pregnancy and childbirth for women born in low-income countries also increased (RR: 6.6 [2.6–16.5]). Those women born in low-income countries were also at higher risk of dying from malignant neoplasm (RR: 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6). Death from mental and behavioural disorders (mainly drug misuse) was significantly more common in women born in high-income countries (RR: 2.4, 95% CI 1.9–3.0) and less common in women born in middle-income countries (RR: 0.3, 95% CI 0.2–0.6). The same pattern was seen in diseases of the circulatory system: women born in high-income countries were at higher risk (RR: 1.2, 95% CI 1.0–1.3), whereas women from middle-income countries were at lower risk (RR: 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.9). Women born in high-income countries also had an increased risk of dying from accidents (RR: 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.5) and suicides (RR: 1.6, 95% CI 1.4–1.8) as compared with Swedish-born women. All immigrant groups were at a higher risk of dying from ‘other external cause’, including assaults, events of undetermined intent, complications of medical and surgical care and sequelae of external causes. The group of ‘other diseases’ was so diverse that no leading cause of death could be distinguished. However, women born in low- or high-income countries were at greater risk of dying from ‘other diseases’ (RR: 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.9 and RR: 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3, respectively) than women born in middle-income countries (RR: 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.9).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that women born in low-income countries are at highest risk of dying during reproductive age in Sweden. They seem to bring with them a pattern from their countries of birth, where death from infectious diseases and maternal deaths are common.9 The high HIV/AIDS mortality in women born in low-income countries may not be surprising, as a majority migrated from countries with a high HIV prevalence and died during the first half of the study period, that is, before the introduction of highly effective antiviral therapy in the mid-1990s. Inadequacies in offering HIV testing may have increased the risk of dying from AIDS for such immigrants in Sweden.19 A higher risk for maternal death among women born in low-income countries has also been observed in other European countries. Besides well-known obstetric risk factors, studies have shown that substandard care, including that caused by communication problems, are more common among immigrants than native-born European women.11,20,21 Moreover, maternal deaths are known to be underreported in low- and high-income countries.22–24 There is reason to believe that additional cases may be concealed under other diagnoses. The slight (although significant) increase in risk of dying from cancer for women from low-income countries that we found contrasts with other Swedish studies showing an equal or lower incidences of cancer for immigrant women from Africa and Asia, as compared with women born in Sweden.25,26

An increased risk of death in women of reproductive age was also seen in women born in high-income countries. A vast majority of these women come from the Nordic countries, a group that in several Swedish studies have shown high death rates7,27 Women from high-income countries are at a higher risk for death due to suicides, accidents, alcohol and drug abuse and circulatory diseases than other groups, in parallel with earlier studies of immigrants from the Nordic countries.4,5

The lower mortality risk among women born in middle-income countries may account for the ‘healthy migrant effect’, i.e. people who migrate are healthier than average,1,28 and the ‘unhealthy re-migrant’ hypothesis, i.e. immigrants with low mortality risk are continually selected for remaining in the host country.29 It is likely that ill-health was a main barrier for labour immigration to Sweden from middle-income countries during the 1950s and 1960s.4 However, in later years, a majority of immigrants arrived as refugees from war-ravaged areas in low- and middle-income countries and may be suspected of being less healthy than labour and social immigrants.30 Immigrants from middle-income countries constitute a heterogeneous group of both labour immigrants and refugees, in contrast to women from low-income countries who mainly come from war-torn areas as refugees. Therefore, there is reason to believe that both the ‘healthy migrant effect’ and the ‘unhealthy re-migrant’ hypothesis might have a stronger impact on women from middle-income countries than women from low-income countries, which is reflected in our results. The ‘healthy migrant effect’ could be also true for women from the low-income countries, when compared with women in their countries of birth who do not migrate, but this would not be detectable in this study. There are studies suggesting a negative selection among the Finnish immigrants that moved to Sweden, i.e. that the socio-economically disadvantaged might have migrated.4,31 This effect might contribute to the increased mortality seen in the group of women born in high-income countries.

The World Bank classification of economies is an alternative tool for characterizing the background of immigrants in terms of socio-economic standards and public health, to using geographical divisions. GNI per capita is strongly associated with most health indicators and has been a better predictor of good health in earlier studies than alternative instruments like the Gini index of national income inequalities, or the more complex human development index, which is less commonly used in health research and available for fewer countries.15,16 The economic and health situation of two neighbouring countries like Afghanistan and Iran, for example, shows great contrasts, whereas both GNI and health indicators between Afghanistan and countries in sub-Saharan Africa such as Somalia and Ethiopia are comparable. No major changes have been seen in the classification of the most common countries of birth for immigrants that moved to Sweden from 1988 to 2007. Although our hypothesis suggesting that women from poor countries would continue to be the most vulnerable group with regard to mortality after migration seems to be true, there seem to be more complex associations between country of birth and death in women of reproductive age from middle- and high-income countries.

A limitation of this study is that no information was available on the reasons for migration, the number of years spent in Sweden or the socio-economic situation of neither the deceased women nor the population used as denominator in the calculations. Refugees are more likely to have experienced violence, food shortages, lack of public health services, discrimination and psychological stress than people who have been able to plan their migration.30 Unfortunately, Sweden has no record of causes of death among asylum seekers (36 207 individuals in 2007). Approximately 17 000 international adoptee girls between the ages of 0 and 10 years arrived in Sweden before 1993 and were, therefore, of reproductive age during the period of our study. Hence, the study population includes an unknown, but probably small, number of international adoptees, the majority of who are born in South Korea, Colombia, India and Sri Lanka.32 These women today are probably in most respects like Swedish-born women. Although the CDR has been known for maintaining high international standards of accuracy,33,34 a well-known problem in mortality studies concerning immigrants is deficiencies in national registration. A considerable number of immigrants do not notify registration authorities in Sweden when they re-migrate, leading to an overestimation of the population and, thereby, an underestimation of mortality.27 There is no evidence of systematic flaws in the coding or registration of causes of death of immigrants in CDR.

The main finding of our study is that the pattern of causes of death varies according to country of birth, and that women born in low-income countries are at the highest risk for death during reproductive age. The grave discrepancy in risk for maternal death and death from infectious diseases between Swedish-born and immigrant women from low-income countries is troublesome. Further research is needed to reveal whatever substandard factors may prevail in the medical services offered to immigrant women of reproductive age. Our results may provide the basis for future research on morbidity and mortality among such immigrant women. Increased awareness about associations between origins and mortality on the part of decision makers and clinicians whose daily practice includes foreign-born patients is necessary if we are to achieve equity in the provision of health care to an entire population.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research [FAS 2007–2026] and by the Medical Faculty, Uppsala University.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points.

Among women of reproductive age, immigrants born in low-income countries are at greatest risk of dying in Sweden.

The greatest difference in mortality rates between Swedish-born women and immigrant women born in low-income countries was seen among women who died from infectious diseases and complications of pregnancy or childbirth.

The World Bank classification of economies provides a simple but useful tool for describing the background of immigrant populations.

Acknowledgements

Preliminary results of this study were presented (in Swedish) at the Swedish Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (SFOG) meeting in Visby, Sweden, on 1 September 2010.

Ethical approval for this study was not needed according to Swedish laws on ethical review, as all subjects were deceased. The Regional Ethics Committee in Uppsala, Sweden, was consulted and confirmed that the study did not fall into the category of research requiring ethical clearance [2008/381, 2009-01-14].

References

- 1.Marmot MG, Adelstein AM, Bulusu L. Lessons from the study of immigrant mortality. Lancet. 1984;1:1455–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91943-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essén B, Hanson BS, Östergren PO, et al. Increased perinatal mortality among sub-Saharan immigrants in a city-population in Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:737–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stirbu I, Kunst AE, Bos V, Mackenbach JP. Differences in avoidable mortality between migrants and the native Dutch in The Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundquist J, Johansson SE. The influence of country of birth on mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease in Sweden 1979-1993. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:279–87. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westerling R, Rosén M. ‘Avoidable’ mortality among immigrants in Sweden. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12:279–86. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos V, Kunst AE, Keij-Deerenberg IM, et al. Ethnic inequalities in age- and cause-specific mortality in The Netherlands. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1112–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albin B, Hjelm K, Ekberg J, Elmståhl S. Mortality among 723,948 foreign- and native-born Swedes 1970-1999. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:511–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DesMeules M, Gold J, McDermott S, et al. Disparities in mortality patterns among Canadian immigrants and refugees, 1980-1998: results of a national cohort study. J Immigr Health. 2005;7(4):221–32. doi: 10.1007/s10903-005-5118-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Geneva: 2008. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibison JM, Swerdlow AJ, Head JA, Marmot M. Maternal mortality in England and Wales 1970-1985: an analysis by country of birth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:973–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuitemaker N, van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, et al. Confidential enquiry into maternal deaths in The Netherlands 1983-1992. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;79:57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salanave B, Bouvier-Colle MH. The likely increase in maternal mortality rates in the United Kingdom and in France until 2005. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1996;10:418–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1996.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Högberg U. An “American dilemma” in Scandinavian childbirth: unmet needs in healthcare? Scand J Public Health. 2004;32:75–7. doi: 10.1080/14034950310022205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Sweden. Stockholm: Statistics Sweden; 2010. Tables on the population in Sweden 2007. http://www.scb.se/statistik/_publikationer/BE0101_2007A001_BR_04_BE0108TAB.pdf (16 July 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schell CO, Reilly M, Rosling H, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of infant mortality: a worldwide study of 152 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:288–97. doi: 10.1080/14034940600979171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindström C, Lindström M. “Social capital,” GNP per capita, relative income, and health: an ecological study of 23 countries. Int J Health Serv. 2006;36:679–96. doi: 10.2190/C2PP-WF4R-X081-W2QN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th edn Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Available at: http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/ (15 January 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 18.The World Bank. World Bank country classification. Available at: http://go.worldbank.org/U9BK7IA1J0 (25 August 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egnell K, Svedhem V. 23% of newly diagnosed HIV cases in 2007 at Karolinska University Hospital had opportunistic infections. J Int AIDS Soc. 2008;11(Suppl 1):P256. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Roosmalen J, Schuitemaker NW, Brand R, et al. Substandard care in immigrant versus indigenous maternal deaths in The Netherlands. BJOG. 2002;109:212–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Essén B, Bødker B, Sjöberg NO, et al. Are some perinatal deaths in immigrant groups linked to suboptimal perinatal care services? BJOG. 2002;109:677–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuitemaker N, Van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, et al. Underreporting of maternal mortality in The Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:78–82. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deneux-Tharaux C, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Underreporting of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States and Europe. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:684–92. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000174580.24281.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elebro K, Rööst M, Moussa K, et al. Misclassified maternal deaths among East African immigrants in Sweden. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:153–62. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemminki K, Li X, Czene K. Cancer risks in first-generation immigrants to Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:218–28. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beiki O, Allebeck P, Nordqvist T, Moradi T. Cervical, endometrial and ovarian cancers among immigrants in Sweden: importance of age at migration and duration of residence. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weitoft GR, Gullberg A, Hjern A, Rosén M. Mortality statistics in immigrant research: method for adjusting underestimation of mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:756–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.4.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1543–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razum O, Zeeb H, Akgun HS, Yilmaz S. Low overall mortality of Turkish residents in Germany persists and extends into a second generation: merely a healthy migrant effect? Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:297–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adanu RM, Johnson TR. Migration and women's health. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;106:179–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silventoinen K, Hammar N, Hedlund E, et al. Selective international migration by social position, health behaviour and personality. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:150–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swedish Intercountry Adoptions Authority (MIA) Anlända utomnordiska adoptivbarn (ålder 0-10 år) Available at: http://www.mia.eu/statistik/varlds.pdf (17 September 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyström L, Larsson LG, Rutqvist LE, et al. Determination of cause of death among breast cancer cases in the Swedish randomized mammography screening trials. A comparison between official statistics and validation by an endpoint committee. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:145–52. doi: 10.3109/02841869509093948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johansson LA, Björkenstam C, Westerling R. Unexplained differences between hospital and mortality data indicated mistakes in death certification: an investigation of 1,094 deaths in Sweden during 1995. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(11):1202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]