Abstract

We systematically examined the effect of different esters for the rhodium-catalyzed intermolecular [5 + 2] cycloaddition of 3-acyloxy-1,4-enynes and alkynes with a concomitant 1,2-acyloxy migration. Significant rate acceleration was observed for benzoate substrates bearing an electron-donating substituent. The cycloaddition can now be conducted at much more practical conditions for most terminal alkynes.

Cycloaddition is one of the most efficient means to construct cyclic compounds by forming at least two bonds in one operation. The importance of the seven-membered ring as a basic structural motif in natural products and pharmaceutical agents continues to inspire the development of novel cycloaddition reactions.1 An important breakthrough in this area is the discovery of vinylcyclopropane (VCP) 1 as a 5-carbon building block by Wender’s group for Rh-catalyzed [5+2] cycloadditions with alkynes, alkenes, and allenes (Scheme 1).2 Research groups of Trost,3 Louie,4 and Fürstner5 developed different metal catalysts for the [5+2] cycloaddition of VCPs and alkynes. Computational studies by Wender, Houk, and Yu elucidated the detailed mechanism for these cycloadditions.6 Recently, new 5-carbon building blocks embedded in substrates 2 and 3 were developed for [5+2] cycloadditions by Yu’s7 and Mukai’s8 groups. The Rh-catalyzed hetero-[5+2] cycloadditions were also realized by Wender9 and Zhang10 using cyclopropyl imines and vinylepoxides, respectively. We recently developed a Rh(I)-catalyzed intramolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of 3-acyloxy-1,4-enyne (ACE) and a tethered alkyne in compound 4 with a concomitant 1,2-acyloxy migration.11 Subsequently, the intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of ACE 5 and various different alkynes was realized (eq 1).12 A highly functionalized seven-membered ring 6 could be prepared in as few as two steps from commercially available starting materials. This intermolecular reaction, however, often requires high loading of rhodium catalyst (10 mol%) and excess alkynes to achieve good yields.

Scheme 1.

Five-Carbon Building Blocks for Rh-Catalyzed [5 + 2] Cycloadditions

Although extensive studies have been conducted in the area of transition metal-catalyzed 1,2-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters, the effect of ester has not been systematically investigated.13 Pivalate was employed in most previous studies including ours. Occasionally, acetate and benzoate were examined. We herein report our systematic study on the effect of the ester in Rh-catalyzed intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of ACEs and alkynes. This investigation has led to the discovery of a new 5-carbon building block that undergoes intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition with alkynes under much more practical conditions.

Pivalate 5a, acetate 5b, and benzoates 5c–5h containing an electron-donating or electron-withdrawing group were prepared from commercially available 3-methyl-1-penten-4-yn-3-ol by esterification (Table 1). We then examined the rate of intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of all ACEs and propargylic alcohol 7 at room temperature using Wilkinson’s catalyst in CDCl3 (eq 2).14 The rate for pivalate 5a was comparable to p-methyl benzoate 5e (entries 1 and 5). The rate for acetate 5b was comparable to non-substituted benzoate 5f (entries 2 and 6). By increasing the electron donating ability from methyl, to methoxy, and to dimethylamino group for benzoates, the reaction rate increased dramatically, peaking at dimethylaminobenzoate 5c with a rate about 46 times faster than the non-substituted benzoate 5f (entries 3–6). The yield of product 6c was nearly quantitative after 4h, suggesting no other competing pathways. The rate was also increased slightly after going towards the more electron withdrawing groups (entries 7 and 8). The 1H NMR spectra of crude products, however, appeared to be very complex for substrates 5g and 5h, suggesting that other competing pathways became dominant. We therefore did not examine more benzoates with electron-withdrawing groups.

Table 1.

Rates of Rh-catalyzed [5+2] Cycloaddition of 5 and propargylic alcohol 7

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ester | Initial ratea,b(min−1) | Ratio of rates 5/5f | ||

| 1 | 5a | 4.05 | 2.72 | ||

| 2 | 5b | 1.01 | 0.68 | ||

| 3 | 5c | 69.0 | 46.3 | ||

| 4 | 5d | 9.38 | 6.30 | ||

| 5 | 5e | 3.09 | 2.07 | ||

| 6 | 5f | 1.49 | 1.00 | ||

| 7 | 5g | 1.80 | 1.21 | ||

| 8 | 5h | 2.78 | 1.87 | ||

rate = % yield/time,

MeNO2 was used as internal standard.

Previously, at least 2.0 equiv of propargylic alcohol 7 and 10 mol % of catalysts were required for the isolation of 81% yield of the cycloaddition product 6a at 65 °C. When p-dimethylaminobenzoate 5c was employed as the new 5-carbon building block, a 97% isolated yield of product 6c could be obtained with just a slightly excess of propargylic alcohol and 0.5 mol % of Wilkinson’s catalyst at 50 °C (entry 1, Table 2). Only one isomer was obtained for cycloaddition products 6c.

Table 2.

Rh-Catalyzed [5 + 2] Cycloaddition of 5c and Alkynes (Ar = p-Me2NC6H4)a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Alkyne Substrates | Yield | Ratio of (9: 9′) | ||||

| 1 | 7 | 6c, 97% | only 6c | ||||

| 2 |

8a,

|

9a, 87% | only 9a | ||||

| 3 |

8b,

|

9b, 89% | >20:1 | ||||

| 4 |

8c,

|

9c, 95% | only 9c | ||||

| 5 |

8d,

|

9d, 96% | 17:1 | ||||

| 6 |

8e,

|

9e, 74% | only 9e | ||||

| 7b |

8f,

|

9f, 58% | >20:1 | ||||

| 8c |

8g,

|

9g, 77% | 8:1 | ||||

| 9 |

8h,

|

9h, 82% | - | ||||

| 10c |

8i,

|

9i, 89% | - | ||||

| 11b |

8j,

|

9j, 77% | 5:1 | ||||

| 12 |

8k,

|

complex mixture | |||||

| 13 |

8l,

|

complex mixture | |||||

Conditions: [Rh(PPh3)3Cl] (0.5 mol %), alkyne 7 or 8 (1.1 equiv), CHCl3 (0.4 M), 50 °C, 24h unless noted otherwise. Isomeric ratios were determined by 1H NMR of crude products.

[Rh(PPh3)3Cl] (2 mol %)

[Rh(PPh3)3Cl] (10 mol %)

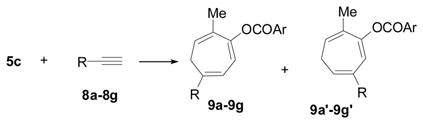

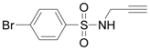

We have examined the intermolecular cycloaddition of ACE 5a and various alkynes in our previous study.12 Some representative alkynes were selected to further test the efficiency of the [5+2] cycloaddition using ACE 5c (Table 2). In the presence of only 0.5 mol% of catalyst, most functionalized terminal alkynes underwent cycloaddition with ACE 5c to afford products in excellent yields and regioselectivity (eq 3 and entries 1–6). The functional group on the propargylic position of these terminal alkynes can be primary alcohol, tertiary alcohol, ether, sulphonamide, or acetonitrile. The efficiency of the cycloaddition was decreased for conjugated enyne 8f (entry 7). Non-functionalized alkyne 8g also participated in the cycloaddition, albeit under higher catalyst loading (entry 8).

Internal alkyne 8h worked smoothly in the presence of only 0.5 mol% metal catalyst (eq 4 and entry 9). We were pleased to find that sensitive substrate such as dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate 8i also produced the desired cycloaddition product, though the catalyst loading need to be increased to 10 mol% (entry 10). Non-symmetric internal alkyne 8j afforded a mixture of two isomers in a ratio of 5:1 (entry 11). The reaction of 5c and internal alkynes 8k or 8l led to low yield of desired products and large amount of unidentified by products under various conditions.

Previously, product 11a was obtained in only 16% yield from pivalate 10a derived from a secondary alcohol using Wilkinson’s catalyst or [Rh(COD)Cl]2 (5 mol %) and (p-CF3C6H4)3P (30 mol %) at 70 °C in CHCl3 (eq 5).12 Longer reaction time or higher temperature did not improve the yield. After switching to substrate 10b, we were able to isolate 53% yield of the desired product 11b in the presence of [Rh(COD)Cl]2 (5 mol %) and (p-CF3C6H4)3P (30 mol %). No improvement was observed for substrate 10b over 10a when Wilkinson’s catalyst was employed.

|

(5) |

As we proposed previously,12 the intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition could be initiated by a Rh-promoted 1,2-acyloxy migration of the propargylic ester in metal complex 13 to form intermediate 14 (Scheme 2). Metallacyclohexadiene 15 could be derived from direct cyclization of metal complex 14, or through carbene 16 via a 6-π electrocyclization. Insertion of alkyne to metallacycle 15 followed by reductive elimination of metallacyclooctatriene 17 would then produce cycloheptatriene product 18 as the major isomer.12 The electron-donating ester may facilitate the reaction in the first nucleophilic attack step from intermediate 13 to 14 or last reductive elimination step from intermediate 17 to product 18. In a gold-catalyzed bis-1,2-acyloxy migration of 1,4-bis-propargylic acetates, the migration aptitude of p-nitrobenzoate was found to be greater than benzoate.15 This suggests that the electron-donating ester likely facilitated the reductive elimination step.16

Scheme 2.

Proposed Mechanism for Rh-Catalyzed Intermolecular [5 + 2] Cycloaddition of ACE and Alkyne

To further understand the 1,2-migration step, we carried out the cross-over experiment for the cycloadditions between ACE 5i12 or 5c and propargylic alcohol 7 (eq 6). No crossover product was observed. This suggests that the acyloxy group in intermediate 13 does not dissociate from the enyne.

|

(6) |

In summary, dramatic rate acceleration was observed for the intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of ACEs and alkynes when the ACE bearing a p-dimethylaminobenzoate was employed as the 5-carbon building block. High yields of cycloaddition products could be obtained at a much lower catalyst loading and with less excess of alkynes. The electronic effect of the ester we observed for intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition not only shed light on the mechanism of the cycloaddition reaction but also have potential broad implications for other transformations involving transition metal-catalyzed 1,2-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Wisconsin and the NIH (R01 GM088285) for financial support. L. C. thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China (20977115 and 21177161) and Chinese Scholarship Council for financial support of the visiting professorship.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [1H NMR, 13C NMR, HRMS, and IR data and copies of NMR specta for all starting materials and products.]. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.For recent reviews on [4+3] cycloadditions, see: Harmata M. Chem Commun. 2010;46:8886. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03620j.Harmata M. Chem Commun. 2010;46:8904. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03621h.Lohse AG, Hsung RP. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:3812. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100260.For recent reviews on [5+2] cycloadditions, see: Pellissier H. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:189.Ylijoki KEO, Stryker JM. Chem Rev. doi: 10.1021/cr300087g.

- 2.For representative examples, see: Wender PA, Takahashi H, Witulski B. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:4720.Wender PA, Husfeld CO, Langkopf E, Love JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:1940.Wender PA, Rieck H, Fuji M. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10976.Wender PA, Glorius F, Husfeld CO, Langkopf E, Love JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:5348.Wender PA, Barzilay CM, Dyckman AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:179. doi: 10.1021/ja0021159.Wegner HA, de Meijere A, Wender PA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6530. doi: 10.1021/ja043671w.Wender PA, Stemmler RT, Sirois LE. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2532. doi: 10.1021/ja910696x.

- 3.(a) Trost BM, Toste FD, Shen H. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2379. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Shen HC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM, Shen HC, Horne DB, Toste FD, Steinmetz BG, Koradin C. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:2577. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuo G, Louie J. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5798. doi: 10.1021/ja043253r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fürstner A, Majima K, Martin R, Krause H, Kattnig E, Goddard R, Lehmann CW. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1992. doi: 10.1021/ja0777180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Yu ZX, Wender PA, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9154. doi: 10.1021/ja048739m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu ZX, Cheong PHY, Liu P, Legault CY, Wender PA, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2378. doi: 10.1021/ja076444d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu P, Cheong PHY, Yu ZX, Wender PA, Houk KN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:3939. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu P, Sirois LE, Cheong PHY, Yu ZX, Hartung IV, Rieck H, Wender PA, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:10127. doi: 10.1021/ja103253d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Xu X, Liu P, Lesser A, Sirois LE, Wender PA, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11012. doi: 10.1021/ja3041724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hong X, Liu P, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. doi: 10.1021/ja309873z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Jiao L, Yuan C, Yu ZX. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4421. doi: 10.1021/ja7100449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiao L, Ye S, Yu ZX. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7178. doi: 10.1021/ja8008715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inagaki F, Sugikubo K, Miyashita Y, Mukai C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:2206. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wender PA, Pedersen TM, Scanio MJC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15154. doi: 10.1021/ja0285013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng JJ, Zhang J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7304. doi: 10.1021/ja2014604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shu X-z, Huang S, Shu D, Guzei IA, Tang W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:8153. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shu X-z, Li X, Shu D, Huang S, Schienebeck CM, Zhou X, Robichaux PJ, Tang W. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5211. doi: 10.1021/ja2109097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For reviews on transition metal-catalyzed acyloxy migration of propargylic esters, see: Marion N, Nolan SP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2750. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604773.Marco-Contelles J, Soriano E. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:1350. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601522.Wang S, Zhang G, Zhang L. Synlett. 2010:692.Shu XZ, Shu D, Schienebeck CM, Tang W. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:7698. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35235d.

- 14.See supporting information for detailed rate study.

- 15.de Haro T, Gomez-Bengoa E, Cribiu R, Huang X, Nevado C. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:6811. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detailed computational studies for the mechanism of this reaction will be reported elsewhere.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.