Abstract

Nocardiosis is a rare disease caused by infection with Nocardia species, aerobic actinomycetes with a worldwide distribution. A rare life-threatening disseminated Nocardia brasiliensis infection is described in an elderly, immunocompromised patient. Microorganism was recovered from bronchial secretions and dermal lesions, and was identified using molecular assays. Prompt, timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment ensured a favorable outcome.

Keywords: Nocardia, Nocardia brasiliensis, nocardiosis

Introduction

Nocardiosis is a rare disease caused by infection with Nocardia species, aerobic actinomycetes with a worldwide distribution usually affecting immunocompromised patients. The systems most commonly involved include the lung, the skin and the central nervous system. We report a rare life-threatening N. brasiliensis infection, the first to be reported from Greece.

Case Report

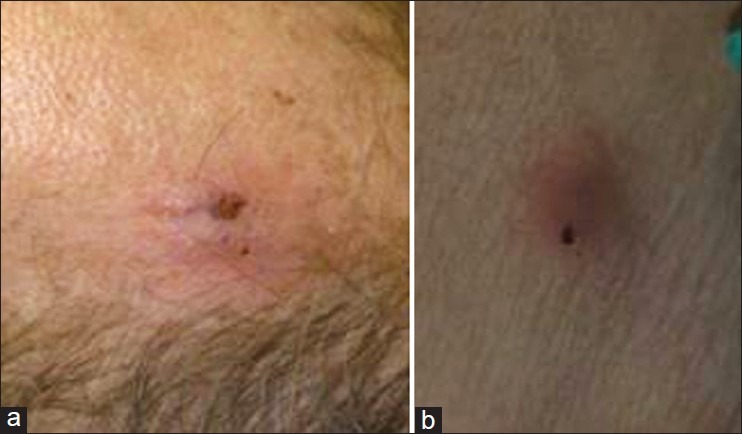

A 67-year-old Caucasian man was referred to the emergency department complaining for dyspnea and fever. The symptoms had started 5 days earlier. The patient had a history of successfully treated non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) 7 years earlier, and was diagnosed with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, unrelated to NHL recurrence, 3 months before admission. He was put on steroids (64 mg) while no prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was given. When he was first seen his was on tapered doses of methylprednisolone (20 mg) and oral cyclosporine. On physical examination the patient was somnolent, his temperature was 38,5°C, blood pressure was 85/45 mmHg and pulse 120/min. Skin examination revealed the presence of intracutaneous nodular lesions (1.5 cm in diameter) on the forehead as well on both forearms [Figures 1a, b], with absence of regional lymphadenopathy. In chest examination crepts were present in both hemithoraces. His arterial blood gases revealed significant hypoxemia (PO2: 56 mmHg in room air). Respiratory and circulatory support was administered, and although hemodynamic stability was achieved, he developed respiratory failure necessitating intubation and admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Figure 1(a and b).

A cutaneous lesion on patients’ forehead and left arm correspondingly

Laboratory workup revealed: hemoglobin 8.2 g/dL, total leucocyte count 8.410/mm3 (94% neutrophils), platelet count 100.000/mm3 and C-reactive protein was elevated at 83.2 mg/dl (normal <0.5). Serum chemistries were within normal limits.

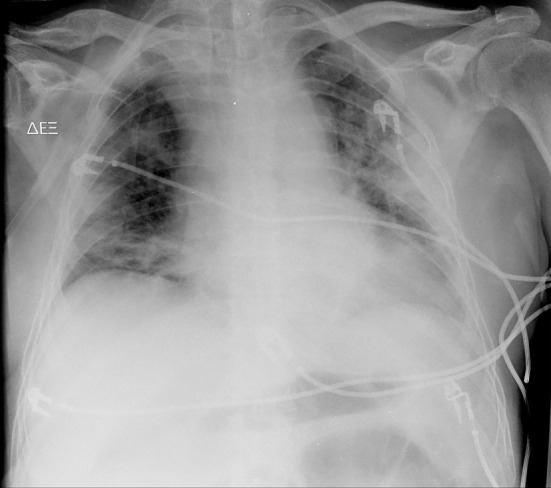

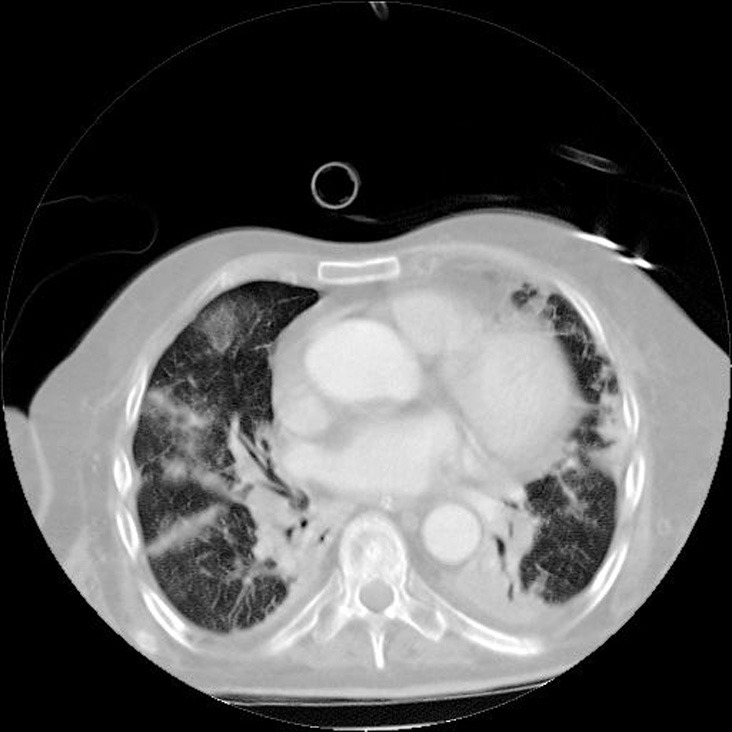

Chest X-rays demonstrated opacity in both lung fields [Figure 2]. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography chest scan showed subsegmental consolidation in right posterior upper segment, right-sided septal thickening, air bronchograms and irregular nodules with cavitation prominent in the anterior upper of the left lobe [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Anteroposterior chest X-ray demonstrating opacity in both lung fields

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan of the chest demonstrating densities and diffuse nodular lesions, some presenting cavitations

Purulent bronchial secretions were collected by bronchoscopy and sent for stains and culture along with material from dermal lesions sampled by needle aspiration.

Direct Gram stain of skin and bronchial secretions revealed the presence of Gram-positive long, obviously branching, thin and finely beaded rods [Figure 4]. Modified Ziehl-Nielsen stain using 1% sulfuric acid as decolorizer, showed the true partially acid-fast nature of the organism. Specimens were cultured using the standard procedure on blood, chocolate, and Sabouraud dextrose agar, on Lowenstein-Jensen medium and in MGIT960 tubes. After 3 days of incubation all cultures grew white colonies, chulky in consistency [Figure 5] with a pungent musty-basement odor. Acid-fast stain of material from a positive MGIT960 tube showed delicate, branching, acid-fast filaments [Figure 6]. The presence of Nocardia spp was suspected and the organism was further identified using molecular techniques.

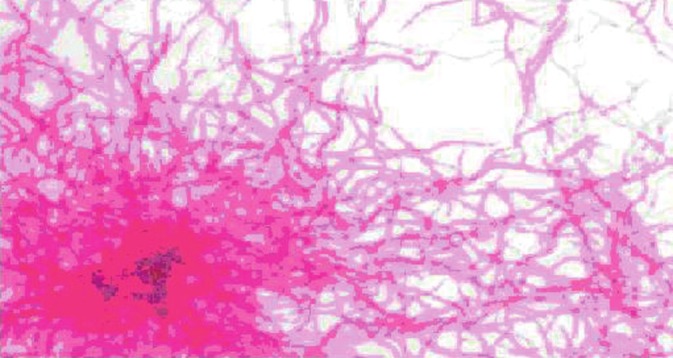

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of sputum smear showing acid fast, beaded filamentous bacteria with typical right angle branching (×2400)

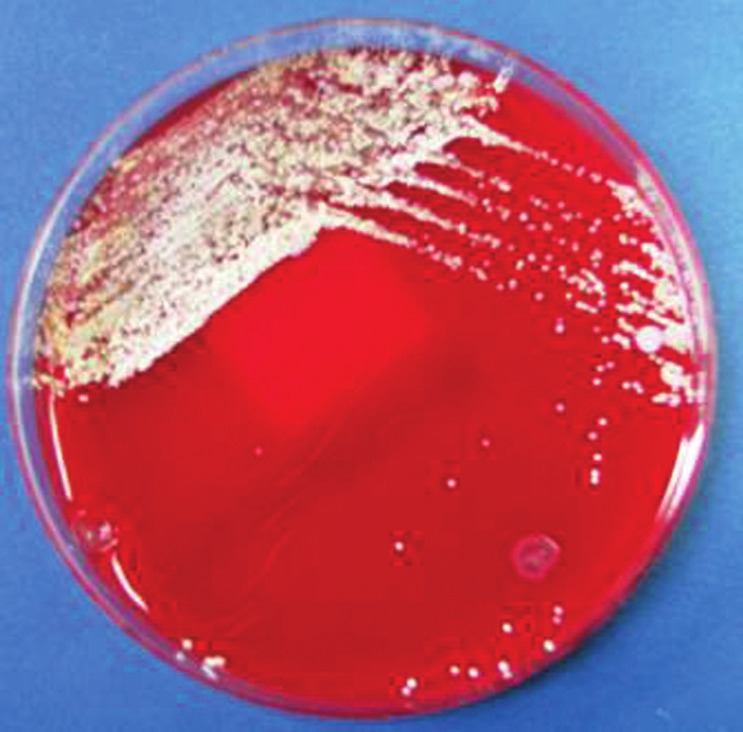

Figure 5.

White, dry chalk colonies of Nocardia brasiliensis after 3 days of incubation at room temperature on Columbia blood agar plate

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of bacteria grown in MGIT960 tubes showing acid fast, beaded filamentous bacteria (×2400).

Of note, our patient was HIV negative and the blood cultures taken were sterile.

The patient was initially treated with imipenem-cilastatin and linezolid. His clinical course was uneventful, with a rapid improvement in lung function leading to extubation 3 days later, accompanied by involution of the subcutaneous nodules. Ten days after his admission to the ICU he was discharged to the ward. He was subsequently treated with intravenous trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole after sensitivity determination was available (TMP-SMX, 10 mg/kg/day of TMP). He was disharged 3 weeks later with on oral TMP-SMX (160/800 mg b.i.d).

Discussion

Nocardiosis is a rare infection (localized or systemic) caused by several species of the genus Nocardia. Nocardiacae belong to the family of actinomycetes. They are aerobic branching Gram-positive bacteria whose bacterial filaments fragment into bacillary and coccoid elements. They are found worldwide and are ubiquitous in the soil. Nocardia asteroides is the predominant human pathogen followed by N. brasiliensis, Nocardia farcinica and Nocardia nova.

Nocardia infections usually occur in situations of cellular immunodeficiency, such as in solid organ or bone marrow transplant recipients, HIV patients, and long-term users of corticosteroids or immunomodulatory agents. Disseminated forms of nocardiosis have been described in immunodeficient hosts while immunocompetent hosts usually present with cutaneous infections.[1] Entry into the body is usually affected through the respiratory system although a cutaneous lesion may be the first clinical manifestation of systemic disease, necessitating exclusion of systemic disease in any nocardial skin infection.

N. brasiliensis is rarely implicated in pulmonary and disseminated infections in immunocompromised patients,[2,3] but these rare cases may be fatal.[3] Disseminated nocardiosis is usually due to other species such as N. asteroides complex. Furthermore, invasive infections initially believed to have been caused by N. brasiliensis, were subsequently attributed to another species, N. pseudobrasiliensis.[4] Our case is the first case of systemic infection caused by N. brasiliensis in Greece. The probable route of entry was the lung.

The geographic prevalence of Nocardia varies dramatically throughout the world.

N. brasiliensis is usually associated with tropical environments, but in the United States it is one of the most commonly isolated types, especially in southeastern and southwestern regions.[4] Although nocardiosis is a rare infection both in Europe and in USA, previous European studies reported that the incidence of primary cutaneous nocardiosis is higher in Europe because N. brasiliensis is more frequently recovered from soil.[5] The first case of N. brasiliensis in Europe has been described in 1968.[6]

According to earlier reports the incidence of nocardiosis is between 500 and 1000 new cases each year in the USA, while in France and Italy it ranges between 150 and 200 and 90 and 130 annual cases, respectively.[7,8] Sporadic cases have been reported in Greece[9,10] while in a recent publication Maraki et al.[11] reported 15 cases in a 5-year period. In this study most patients were male and their mean age was 64 years. Most of them had an underlying predisposing condition. N. brasiliensis was isolated in seven immunocompetent patients presenting as primary cutaneous nocardiosis. In an Italian study, four cases of N. brasiliensis were revealed in a 9–year period.[12] An analysis of all cases of N. brasiliensis in Europe since 1990 in the same study showed that cases predominantly presented as cutaneous infections, with only a few cases presenting as pulmonary disease or bloodstream infection.

Standard therapy of Nocardia infections is trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Other treatment options in cases of drug intolerance include amikacin, imipenem, third-generation cephalosporins, minocyclin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or recently, linezolid.

In immunosuppressed patients a high clinical suspicion index for Nocardia infection is necessary because a delay in diagnosis could lead to severe complications and worsen prognosis. Microbiological identification of the pathogen to species level may augment in understanding the actual burden of disease imposed by each species of the genus Nocardia, given their relevant rarity and their potential for life-threatening disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Threlkeld SC, Hooper DC. Update on management of patients with Nocardia infection. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 1997;17:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smego RA, Jr, Gallis HA. The clinical spectrum of Nocardia brasiliensis infections in the United States. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:164–80. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wadhwa V, Rai S, Kharbanda P, Kabra S, Gur R, Sharma VK. A fatal pulmonary infection by Nocardia brasiliensis. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24:63–4. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.19900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruimy R, Riegel P, Carlotti A, Boiron P, Bernardin G, Monteil H, et al. Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis sp nov, a new species of Nocardia which groups bacterial strains previously identified as Nocardia brasiliensis and associated with invasive diseases. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:259–64. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saubolle MA. Aerobic actinomycetes. In: Mc-Clatchey KD, editor. Clinical laboratory medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1201–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boiron P, Provost F, Chevrier G, Dupont B. Review of nocardial infections in France, 1987-1990. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:709–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01989975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farina C, Boiron P, Ferrari I, Provost F, Goglio A. Report of human nocardiosis in Italy between 1993 and 1997. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:1019–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1020010826300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scharfen J. Nocardia brasiliensis in Czechoslovakia. Comparative studies of 2 strains isolated from mycetomas. Cesk Epidemiol Mikrobiol Immunol. 1968;17:304–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christidou A, Maraki S, Scoulica E, Mantadakis E, Agelaki S, Samonis G. Fatal Nocardia farcinica bacteraemia in a patient with lung cancer. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;50:135–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maraki S, Scoulica E, Alpantaki K, Dialynas M, Tselentis Y. Lymphocutaneous nocardiosis due to Nocardia brasiliensis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47:341–4. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maraki S, Scoulica E, Nioti E, Tselentis Y. Nocardial infection in Crete, Greece: Review of fifteen cases from 2003 to 2007. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:122–7. doi: 10.1080/00365540802651905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farina C, Andrini L, Bruno G, Sarti M, Franc M, Tripodi O, Utili R, et al. Nocardia brasiliensis in Italy: A nine-year experience. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39:969–74. doi: 10.1080/00365540701466124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]