Abstract

Carbapenem antibiotics have become therapeutics of last resort for treatment of difficult infections. Emergence of class A β-lactamases that have the ability to inactivate carbapenems in the past few years is a disconcerting clinical development, in light of the diminished options for treatment of infections. A member of the GES-type β-lactamase family, GES-1, turns over imipenem poorly, but the GES-5 β-lactamase is an avid catalyst for turnover of this antibiotic. We report herein the high-resolution x-ray structures of the apo GES-5 and GES-1 and GES-5 β-lactamases in complex with imipenem. These are the first structures of native class A carbapenemases with a clinically used carbapenem antibiotic in the active site. The structural information was supplemented by information from molecular dynamics simulations, which collectively for the first time disclose how the second steps of catalysis by these enzymes, namely the hydrolytic deacylation of the acyl-enzyme species, takes place effectively in the case of the GES-5 β-lactamase and significantly less so in GES-1. This information illuminates one evolutionary path that nature has taken in the direction of inexorable emergence of resistance to carbapenem antibiotics.

β-Lactam antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, monobactams and carbapenems) constitute the most extensively used class of antibacterial agents for treatment of a wide-variety of infections.1 More than seven decades of use of these antibiotics has resulted in selection and widespread dissemination of β-lactam-resistant bacteria. Among these, resistance to carbapenems is the most disconcerting, as these broadly resistant organisms are causes of high mortality. The major mechanism of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Gram-negative bacteria is the catalytic action of β-lactamases, hydrolytic enzymes that inactivate the antibiotics.2,3 The enzymes are divided into four major classes, A, B, C and D.4 β-Lactamases of classes A, C and D are active-site serine enzymes, whereas those belonging to class B are zinc dependent.

The prototypical class A TEM and SHV β-lactamases were among the first β-lactamases identified in Gram-negative bacteria. Those early resistance enzymes had a narrow-spectrum substrate profile that included primarily penicillins and some early cephalosporins. Progressive introduction of subsequent generations of β-lactam antibiotics led to an inexorable emergence of novel enzymes with enhanced catalytic competencies.5 In response to the challenge of organisms with class A β-lactamases, the first carbapenem, imipenem, was brought to the clinic in the mid-1980s. Shortly thereafter newer carbapenems, meropenem, doripenem and ertapenem, were introduced. Carbapenems rapidly became antibiotics of last resort, because of their exceptional breadth of activity and potency. As a point of departure in evolution of β-lactamases, the common TEM- and SHV-type enzymes failed to evolve the ability to turn over carbapenems. Indeed, carbapenems serve as inhibitors of these enzymes, as they are able to acylate the active-site serine, but this intermediate does not undergo deacylation to regenerate the catalyst.6,7 The first insight into this process came from the x-ray structure of the acyl-enzyme species of the TEM-1 β-lactamase with imipenem, which explained the inhibition process.6 The hydrolytic water molecule is pushed away from the active site by imipenem, and there is an additional hydrogen bond to the substrate which adversely affects its activation. This arrangement imparts longevity to the acyl-enzyme species, resulting in inhibition of the enzyme.

Nonetheless, extensive use of carbapenems has lead to acquisition of specific class A enzymes with hydrolytic activities against them. These enzymes, which share less than 50% amino-acid sequence identity with the TEM- and SHV-type β-lactamases, are found in clinical and environmental strains and include NMCA, IMI, SFC, SME, GES and KPC carbapenemases.8 In contrast to the other members of this group of enzymes, the genes for the KPC- and GES-type β-lactamases have disseminated widely in clinics all over the world.9 Currently, 12 variants of KPC- and 22 of GES-type enzymes have been reported. Unlike the narrow-spectrum TEM-1 enzyme, KPC- and GES-type β-lactamases are capable of hydrolyzing extended-spectrum cephalosporins.8 Additionally, all KPC-type enzymes studied enhance resistance to carbapenems. Among the GES-type β-lactamases, only variants with N170S substitutions reduce susceptibility to carbapenems.8 The ability of the KPC enzymes and some GES variants to hydrolyze the majority of available β-lactam antibiotics, including carbapenems, constitute an immense challenge to our ability to treat life-threatening infections caused by pathogens producing these β-lactamases.8–11

Kinetic studies have demonstrated that GES-5 has a 100-fold enhancement in the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) against the carbapenem antibiotic imipenem over the marginal activity exhibited by GES-1.12 The consequence of this is that GES-5 has become a bona fide carbapenemase of clinical importance, whereas the poor activity of GES-1 against carbapenems is in par with that of TEM-1, for which carbapenems serve as covalent inhibitors.12,13 The GES-1 and GES-5 β-lactamases, hence, provide a unique opportunity to explore the structural means for the broadening of the substrate profile to include carbapenems. We report herein the x-ray structures of the acyl-enzyme complexes of GES-1 and GES-5 carbapenemases with imipenem. By soaking crystals with imipenem for a short duration, followed by flash cooling, we succeeded in generating the acyl-enzyme species for both the wild-type GES-1 and GES-5. These are the first enzyme-substrate complexes of a native class A carbapenemase with a clinically important carbapenem antibiotic. These structures, complemented by dynamics simulations, shed light on how the activity of GES-5 was enhanced to include carbapenems as substrates.

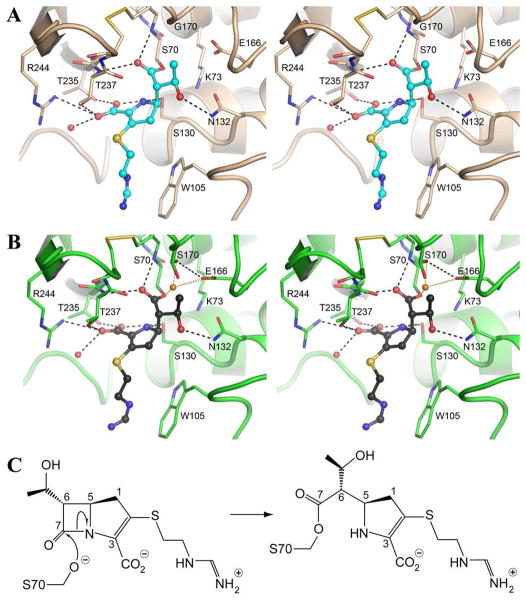

The crystal structures of the apo GES-5 and imipenem complexes of GES-1 and GES-5 were determined to 1.10-, 1.15- and 1.25-A resolution, respectively (Figures 1A and 1B, SI Table S1, SI Table S2 and SI Figure S1). The crystals were grown under the same conditions and all three structures contain two molecules in the asymmetric unit, related by a non-crystallographic two-fold rotation. The enzyme-substrate complexes were generated by soaking GES-1 and GES-5 crystals in 30 mM imipenem for times varying from 30 second to 10 minutes. Although the presence of imipenem in the active sites of the two enzymes could be observed in data from crystals soaked for as briefly as 30 seconds, two-minute soaking experiments were used for the detailed comparison of the incorporation of the drug. Initial electron density for the GES-1 and GES-5 imipenem complexes is shown in Supporting Information (SI Figure S2). In both cases there was no visible density for the side chain attached to the C2-sulfur, as it points to the milieu and should be mobile. The occupancy of imipenem was refined for both enzyme molecules in each crystal, resulting in values of 0.94 and 0.96 for GES-1, and 0.63 and 0.67 for GES-5. As indicated earlier, imipenem is a good substrate for GES-5, hence the lower occupancy of the substrate is indicative of partial deacylation. This is supported by analysis of the substrate occupancies in GES-5 at different soaking times. After 30 s the occupancies (0.53/0.54) are only slightly lower than those at 2 min, and after 5 min they are essentially the same (0.67/0.68) as at 2 min, suggesting that the competing acylation and deacylation steps reach an equilibrium rapidly and plateau at about two-thirds occupancy. In GES-1 full occupancy is seen after 1 min, supporting the premise that this enzyme is covalently inhibited by carbapenems. The active-site residues that have been identified as playing critical roles in the class A β-lactamases are all conserved in both GES-1 and GES-5, including Ser70, Lys73, Ser130, Asn132, Glu166 and Thr237 (Ambler numbering scheme14). The only exception is residue 170. This residue is asparagine in most class A enzymes, whereas in GES-1 and GES-5 it is a glycine and a serine, respectively. In the GES-5-imipenem complex, two rotamers of the serine were observed in one of the molecules (Figure 1B), and only one in the second. In both complexes the β-lactam ring of imipenem is opened and a covalent bond to Ser70 side chain has formed (Figure 1C). The ester carbonyl of the acyl enzyme intermediate is housed in the oxyanion hole formed by the main-chain nitrogen atoms of Ser70 and Thr237. The C3 carboxylate is directed towards a pocket formed by the side chains of residues Ser130, Thr235, Thr237 and Arg244, and the hydroxyethyl moiety of imipenem points toward the Glu166 and Asn132 side chains. In both GES-1 and GES-5, imipenem makes a total of seven hydrogen bonds with the surrounding protein molecule and additional hydrogen bonds to well-ordered water molecules (Figures 1A and 1B). In both complexes the hydroxyethyl moiety is oriented such that the hydroxyl group points away from the Ser70 and makes a hydrogen bond with the Nδ2 atom of the conserved Asn132 (Figure 2A and 2B). The methyl of the hydroxyethyl points in the direction of residue 170. The formation of the GES-1 acyl-enzyme intermediate displaces the deacylating water molecule observed in the apo GES-1 structure.15

Figure 1.

Imipenem acyl-enzyme intermediate complexes. (A) Stereo view of the GES-1 active site with the bound imipenem (cyan) showing the hydrogen bonding interactions with the protein as dashed black lines. (B) Stereo view of the GES-5 active site with the bound imipenem (black). The partially occupied water molecule is shown as a gold sphere, with its hydrogen-bonding interactions shown as dotted gold lines. (C) Imipenem (left) acylates Ser70 (right).

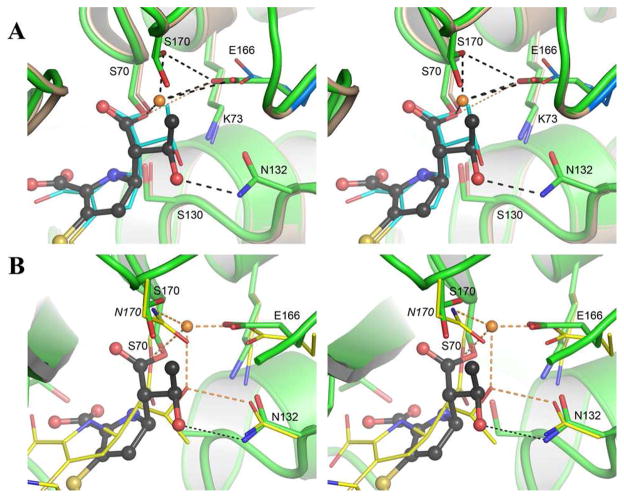

Figure 2.

Stereo views of the superimposition of GES-1, GES-5 and TEM-1. (A) The active site of GES-1 (pink) and GES-5 (green), showing the two alternate conformations of Ser170 and the closer approach of the Glu166 to Ser70 in GES-5. The position of Glu166 in GES-1 is shown in blue. The imipenem is shown in black ball-and-stick for GES-5 and thin cyan sticks for GES-1. The hydrogen bonds with the partially occupied water molecule are shown as black dashed lines, and the hydrogen bond between Glu166 and Ser70 is shown as a dotted gold line. (B) The active site of GES-5 (green) and the imipenem complex of TEM-1 (yellow). The position of the imipenem in TEM-1 is shown as thin yellow sticks, and the GES-5 imipenem as black ball-and-stick. The deacylating water in TEM-1 is shown as gold sphere with four hydrogen-bonding interactions depicted as dashed gold lines.

Superimposition of the two GES-imipenem complexes gives an almost perfect overlap of the two structures (0.1 A rmsd for all 268 Cα atoms). The presence of the serine side chain at position 170 has a profound effect on the conformation of the GES-5 active site, with the Glu166 side chain, the general base that promotes a water molecule for deacylation,16 moving toward the active site Ser70 by approximately 1 A compared to GES-1 (Figures 1B and 2A, SI Figure S3). Glu166 now makes a new hydrogen-bonding interaction with one of the conformations of the Ser170 side chain. This new hydrogen-bonding interaction was also observed in the apo GES-5 structure (SI Figure S4). The side chain of Glu166 is much closer to the catalytic serine residue (Ser70), such that there is a hydrogen bond (3.2 A) between the Oε1 atom of the Glu166 and the Oγ of Ser70, and this proximity closes the pocket typically occupied by the hydrolytic water molecule (Figure 2A). Such a hydrogen bond between the Glu166 and Ser70 side chains is rare in the class A β-lactamases and has only been observed once in the SME-1 β-lactamase.17 In this robust carbapenemase, there is also no deacylating water molecule, which suggests that in SME-1 and GES-5 a transient water molecule from the milieu could serve this role. In molecule B of the GES-5 imipenem complex, the orientation of the Ser170 side chain is such that there is no hydrogen bond to Glu166, and the latter residue adopts two distinctly different conformations, one similar to that observed in molecule A of this complex, and the other shifted away from Ser70 in a configuration reminiscent of GES-1 (Figure 2A). These rotamer conformations observed in the GES-5 structure were sampled in our molecular dynamics (described below), and the presence of a hydrogen-bonding interaction between Ser170 and Glu166 has been found to be vitally important for carbapenemase activity (also discussed below).

The superimposition of GES-1 and GES-5 shows that the conformation of imipenem is essentially identical in both enzyme complexes (Figure 2A), with an rmsd of only 0.4 A when just the two imipenem molecules are superimposed. Binding of imipenem does not lead to any significant conformational changes in the active site of these enzymes, compared to the apo structures. Superimposition of GES-1 and GES-5 imipenem complexes onto the apo forms of the enzymes based upon all the atoms in segments of structure that contain the important active-site residues (positions 70–73, 129–133, 165–171 and 234–240), gave rmsd values of 0.32 and 0.20, respectively (SI Figure S5). However, in contrast to apo GES-5, a water molecule is observed in the GES-5-imipenem complex (Figures 1B and 2A) occupying a site similar to that assigned to the deacylating water in GES-1.15 The electron density for this water molecule appeared later in the refinement, and has a refined occupancy of 0.30 and 0.35 in the two independent GES-5 molecules. It is anchored by hydrogen-bonding interactions to Ser70 and Glu166, with an additional hydrogen bond to one of the Ser170 conformations in molecule A (Figure 2A), and is displaced toward the acyl intermediate by about 1 A relative to the position observed in apo GES-1. It would appear that in this location the water molecule would make two very short contacts to the bound imipenem, 2.5 A to the ester carbonyl carbon and 1.3 A to the methyl of the hydroxyethyl moiety. These distances preclude imipenem and the water molecule occupying the active site at the same time. The low occupancy of the water molecule (0.30–0.35) and the corresponding higher occupancy of the imipenem (0.63–0.67) would indicate that when imipenem is present in the active site of GES-5, the water molecule is absent. A question then remains as to why acylation of the active-site serine in the prototypic class A β-lactamase TEM-1, and in GES-1 inhibits enzyme activity, whereas in GES-5 there is progress toward improved catalysis such that this enzyme could be called a bona fide carbapenemase. The puzzle is tantalizing, especially with the availability of x-ray crystal structures for all three enzymes acylated by imipenem and the fact that the complexes with imipenem of GES-1 and GES-5 (this study) would appear nearly identical, with the exception of the different amino acids found at position 170 (Gly and Ser, respectively). This last observation indicates to us that molecular dynamics in these complexes might have a role to play in manifesting the mechanistic outcomes.

An analysis of the TEM-1 β-lactamase-imipenem complex indicates that the orientation of the hydroxyethyl group of the imipenem is a determining factor in longevity of the acyl-enzyme species.6 The hydroxyl of the hydroxyethyl substituent makes hydrogen-bonding interactions with the Oδ1 atom of Asn132 and also with the hydrolytic water molecule (Figure 2B). This water molecule is involved in four hydrogen bonds. This extensive solvation of the water molecule might diminish its nucleophilicity.6,7 The hydroxyl of the hydroxyethyl moiety actually occupied the position of the hydrolytic water molecule, which is displaced to the position seen in the structure of the complex. In this arrangement, the hydroxyethyl moiety presents an impediment to the travel of the hydrolytic water molecule to the acyl carbonyl, hence the stability of the complex.

Comparison of the structures of the imipenem complexes of GES-1 and GES-5 with that of the TEM-1 β-lactamase6 shows that in the TEM-1 enzyme the entire imipenem molecule has moved across the active site by approximately 1.7 A, in the direction away from Asn132 and Glu166 and toward Arg244 (Figure 2B). Importantly, the hydroxyethyl group in the GES complexes has rotated approximately 120° relative to the TEM-1 complex, such that it does not make a hydrogen bond with the hydrolytic water molecule. As a result, the hydroxyethyl rotamer observed in the GES-1 and GES-5 complexes would not be expected to interfere with the effective activation of the hydrolytic water molecule. This is one factor, but dynamics of the protein would appear to play a role in catalysis as well, as described below.

To understand the favorable turnover of imipenem by GES-5, we used the x-ray structures for the acyl-enzyme species of GES-5 and of TEM-1 with imipenem for dynamics simulations. During 11 ns of dynamics simulations, we noted that the side chains of Glu166 and Ser170 of the GES-5 enzyme remained in contact with one another for the duration (Figures 3A and 3B). But this was not the case for Glu166 and Asn170 of the TEM-1 structure; with ~15% of the snapshots exhibiting hydrogen bonding between the two residues (data not shown). As we will explain, this interaction is important for the carbapenemase activity.

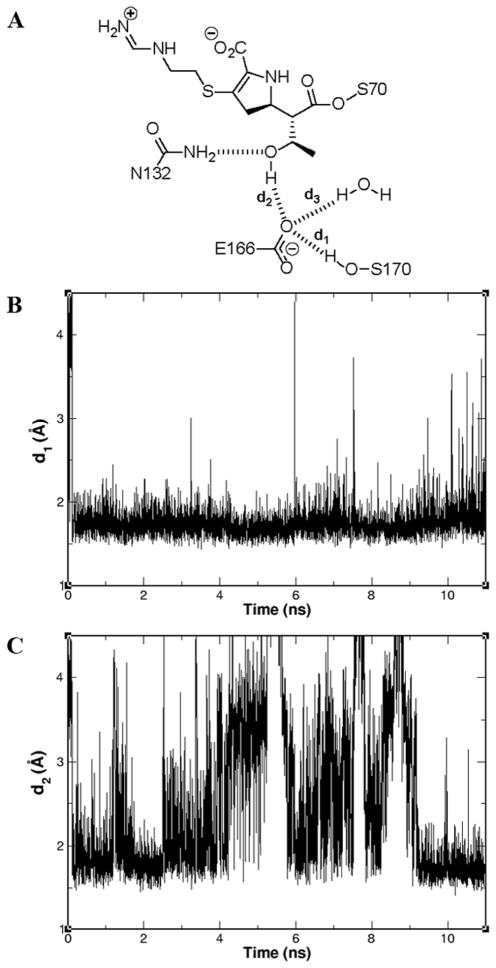

Figure 3.

Molecular dynamics simulations of GES-5 acylated by imipenem. (A) A cartoon of a representative snapshot, with distances d1, d2 and d3 indicated. Hydrogen bonds are shown in dashed lines. Fluctuations of the distances d1 (B) and d2 (C) as a function of the 11 ns of the molecular dynamics are depicted.

In representative snapshots of the simulations of GES-5, Glu166 makes three hydrogen bonds, to Ser170 (Figure 3B), to hydroxyl of imipenem (Figure 3C) and to hydrolytic water (SI Figure S6). This brings about two effects: first, it tethers the hydroxyethyl group away from the trajectory of the hydrolytic water, assisted by the hydrogen bond between Asn132 and the hydroxyl of the hydroxyethyl group (Figure 3A). Second, it allows Glu166 to be in position to activate the hydrolytic water. The implication of the stable hydrogen bond between Glu166 and Ser170 for the GES-5 enzyme is that the side chain of Glu166 remains in position at all times to interact with the hydrolytic water in promoting it for the deacylation step.

In TEM-1, and by extension in the GES-1 enzyme as well (see below), the situation is different. The presence of Asn at position 170 of TEM-1 disrupts this arrangement. First, Asn170 has a longer side chain that sterically does not allow a large enough opening for a water to come close to the ester carbonyl of the imipenem complex. But more importantly, molecular dynamics snapshots of TEM-1 sampled Asn170 and Glu166 in hydrogen-bonding arrangement only ~15% of the times (SI Figure S7). This lack of tethering of Glu166 allowed a larger sampling of the side-chain rotamers in the complex with imipenem. The interaction of the hydrolytic water molecule and the side chain of Glu166 is lost in TEM-1 and as such the water molecule is not properly positioned within the active site to perform deacylation. This effect would dominate in GES-1 with Gly at position 170, which obviously cannot interact with Glu166 at all. So, the higher turnover efficiency of imipenem observed for GES-5 is due to the special role that Ser170 plays, which must have been a force in its selection for the carbapenemase activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health grant AI057393 (SBV). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy (BES, BER) and by the National Institutes of Health (NCRR, BTP, NIGMS). The project was also supported by Grant Number 5 P41 RR001209 from the NCRR.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Procedures for protein expression, purification, crystallization, data collection, structure determination and molecular dynamics simulations; table of crystallographic data; table of crystallographic refinement; figures of the overall molecular structure, electron density, the apo GES-5 active site, superimpositions of two complexes with their respective apo enzymes. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Testero SA, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. Antiinfectives. In: Abraham DJ, Rotella DP, editors. Burger’s medicinal chemistry, drug discovery and development. Vol. 7. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford: 2012. pp. 259–404. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush K. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bush K. Crit Care. 2010;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/cc8892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S. Chem Rev. 2005;105:395–424. doi: 10.1021/cr030102i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush K, Mobashery S. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;456:71–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maveyraud L, Mourey L, Kotra LP, Pedelacq JD, Guillet V, Mobashery S, Samama JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9748–9752. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nukaga M, Bethel CR, Thomson JM, Hujer AM, Distler A, Anderson VE, Knox JR, Bonomo RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12656–12662. doi: 10.1021/ja7111146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walther-Rasmussen J, Hoiby N. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:470–482. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Queenan AM, Bush K. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies TA, Queenan AM, Morrow BJ, Shang W, Amsler K, He W, Lynch AS, Pillar C, Flamm RK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2298–2307. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh TR. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:367–371. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328303670b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frase H, Shi Q, Testero SA, Mobashery S, Vakulenko SB. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29509–29513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.011262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zafaralla G, Mobashery S. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1505–1506. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambler RP, Coulson AFW, Frere JM, Ghuysen JM, Joris B, Forsman M, Levesque RC, Tiraby G, Waley SG. Biochemical J. 1991;276:269–270. doi: 10.1042/bj2760269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CA, Caccamo M, Kantardjieff KA, Vakulenko S. Acta Crystallogr. 2007;D63:982–992. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907036955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meroueh SO, Fisher JF, Schlegel HB, Mobashery S. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15397–15407. doi: 10.1021/ja051592u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sougakoff W, L’Hermite G, Pernot L, Guillet V, Naas T, Nordmann P, Jarlier V, Delettre J. Acta Crystallogr. 2002;D58:267–274. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901019606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.