Abstract

Objective To assess the impact of controlled cord traction on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and other characteristics of the third stage of labour in a high resource setting.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Five university hospital maternity units in France.

Participants Women aged 18 or more with a singleton fetus at 35 or more weeks’ gestation and planned vaginal delivery.

Interventions Women were randomly assigned to management of the third stage of labour by controlled cord traction or standard placenta expulsion (awaiting spontaneous placental separation before facilitating expulsion). Women in both arms received prophylactic oxytocin just after birth.

Main outcome measure Incidence of postpartum haemorrhage ≥500 mL as measured in a collector bag.

Results The incidence of postpartum haemorrhage did not differ between the controlled cord traction arm (9.8%, 196/2005) and standard placenta expulsion arm (10.3%, 206/2008): relative risk 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.79 to 1.15). The need for manual removal of the placenta was significantly less frequent in the controlled cord traction arm (4.2%, 85/2033) compared with the standard placenta expulsion arm (6.1%, 123/2024): relative risk 0.69, 0.53 to 0.90); as was third stage of labour of more than 15 minutes (4.5%, 91/2030 and 14.3%, 289/2020, respectively): relative risk 0.31, 0.25 to 0.39. Women in the controlled cord traction arm reported a significantly lower intensity of pain and discomfort during the third stage than those in the standard placenta expulsion arm. No uterine inversion occurred in either arm.

Conclusions In a high resource setting, the use of controlled cord traction for the management of placenta expulsion had no significant effect on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and other markers of postpartum blood loss. Evidence to recommend routine controlled cord traction for the management of placenta expulsion to prevent postpartum haemorrhage is therefore lacking.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01044082.

Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage remains a major complication of childbirth worldwide.1 Population based studies in high resource countries report a prevalence of severe postpartum haemorrhage of 0.5% to 1% of deliveries,2 3 4 5 making it the main component of severe maternal morbidity. Uterine atony is the leading cause of postpartum haemorrhage, accounting for 60-80% of cases.6 Prevention of atonic postpartum haemorrhage is thus crucial, and preventive measures are recommended for all women giving birth, given that individual risk factors are poor predictors.

Active management of the third stage of labour has been proposed for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage.7 The standard definition for active management combines three procedures: an oxytocic drug administered immediately after birth, early cord clamping and cutting, and controlled cord traction. Several trials8 9 10 11 in a meta-analysis12 showed that active management of the third stage of labour is associated with a 60% reduction in the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage compared with expectant management. Given its efficacy, active management of the third stage of labour has been included in international13 14 and national15 16 17 guidelines for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage. An adequate evaluation of the specific efficacy of each of its components, however, has not been done. The independent efficacy of using a preventive oxytocic has been shown with a good level of evidence18 and is therefore often considered the essential component of active management of the third stage of labour. This is not the case for controlled cord traction.19 Although most guidelines for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage include controlled cord traction, actual implementation is highly variable; in Europe ranging from 12% in Hungary to 95% in Ireland.20 In countries such as France, where controlled cord traction is not recommended, pulling the cord in the absence of any sign of placenta separation is considered poor practice because of the potential risk of uterine inversion.21

The variation in use of controlled cord traction may be explained by the paucity of available evidence for assessing the efficacy of controlled cord traction for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage or its potential risks. Until recently only two trials conducted in the 1960s19 22 and with important limitations had assessed the specific effect of controlled cord traction and they had conflicting results. Recently, a large randomised controlled trial conducted in eight low and middle income countries reported that the risk of severe postpartum haemorrhage was not increased by the omission of controlled cord traction as part of the active management of the third stage of labour.23 The authors concluded that controlled cord traction could be omitted in non-hospital settings. However, the results of this trial may be relevant for low and middle income countries and not applicable to other countries. We therefore assessed the impact of controlled cord traction on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and other characteristics of the third stage of labour in a high resource setting.

Methods

The TRACOR (TRAction of the CORd) trial was a multicentre randomised controlled trial with two parallel groups and took place in five French university hospitals between 1 January 2010 and 31 January 2011.

Controlled cord traction was not a standard part of the management of third stage labour in any of the participating units. Before the trial began, we trained all staff who were likely to recruit women into the trial (midwives and obstetricians) in the trial procedures and more particularly in the technique of controlled cord traction. A team from the steering committee led several training meetings in each participating centre, pairing a midwife with an obstetrician. Films showed the placement of the collector bag and the practise of controlled cord traction. After this initial training, one month was devoted to using controlled cord traction in actual practice. Before the recruitment period, we organised a meeting in each unit to verify the attendants’ adherence to the protocol and their ease in practising the relevant procedures.

Participants

Women were eligible for inclusion if aged 18 or more with a singleton fetus at 35 or more weeks’ gestation and with a planned vaginal delivery. We excluded women with a severe haemostasis disease, placenta praevia, in utero fetal death, and multiple gestations and those who did not understand French. A midwife or obstetrician offered eligible women information about the study during a prenatal visit during the third trimester. This information was repeated when the women arrived in the delivery room; the women then confirmed their participation and provided informed written consent.

Interventions

We compared controlled cord traction with standard management of placental expulsion. In the intervention arm, controlled cord traction was implemented immediately after delivery with a uterine contraction.19 Briefly, after birth controlled cord traction was started with a firm uterine contraction without waiting for placental separation. The lower segment was grasped between the thumb and index finger of one hand and steady pressure exerted upwards; at the same time the cord was held in the other hand and steady cord traction exerted downwards and backwards, exactly countered by the upwards pressure of the first hand, so that the position of the uterus remained unchanged. If the placenta was not expelled on the first attempt, controlled cord traction was repeated using counter pressure with the next uterine contraction.

In the control arm, the attendant awaited the signs of spontaneous placental separation and descent into the lower uterine segment. Once the placenta was separated it was delivered through the mother’s efforts (helped by fundal pressure or soft tension on the cord to facilitate placental expulsion through the vagina if needed). This standard placental expulsion is the usual management in France, as taught in university hospitals and midwifery schools, and it was the routine procedure in the five participating centres before the trial.

All other aspects of management of the third stage were identical in both arms: intravenous injection of 5 IU oxytocin and clamping and cutting of the cord within two minutes of birth; placement of a graduated (100 mL graduation) collector bag (MVF Merivaara France) just after birth, left in place until the birth attendant judged that bleeding had stopped and that there was no reason to monitor further,24 and always at least for 15 minutes; and manual removal of the placenta at 30 minutes after birth if not expelled. A blood sample was taken from all women on the second day after delivery to measure haemoglobin level and haematocrit.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of the trial was the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage, defined by a blood loss of ≥500 mL, measured with a graduated collector bag.25 The main secondary outcomes were other objective measures of postpartum bleeding: measured blood loss ≥1000 mL at bag removal, mean measured blood loss at 15 minutes after birth (the bag had to be left in place at least 15 minutes to have one measure of blood loss at the same time point in all women), mean measured postpartum blood loss at bag removal, and mean changes in peripartum haemoglobin level and haematocrit (difference between haemoglobin level and haematocrit before delivery and at day 2 postpartum). Other secondary outcomes included use of supplementary uterotonic treatment; postpartum transfusion (until discharge); arterial embolisation or emergency surgery for postpartum haemorrhage; other characteristics of the third stage, including duration, manual removal of the placenta; and women’s experience of the third stage, assessed by a self administered questionnaire on day 2 postpartum. Safety outcomes included uterine inversion, cord rupture, and pain.

The detail of procedures used to manage the third stage, as well as all clinical outcomes identified during the immediate postpartum period, were prospectively collected by the midwife or obstetrician in charge of the delivery and recorded in the woman’s electronic form in the labour room. Other data were collected by a research assistant, independent of the local medical team. An independent data monitoring committee, which met monthly, was responsible for reviewing adherence to the trial procedures, recruitment, and safety data; the quality of collected outcome data was checked in each centre for 10% of the included women, randomly selected, and in all cases of postpartum haemorrhage.

Sample size

We assumed a 7% incidence of postpartum haemorrhage in the absence of controlled cord traction. This incidence is that found in the cohort as a whole in the Pithagore6 trial in six French perinatal networks in 2006 from a total of about 147 000 births.26 We hypothesised that controlled cord traction may explain half of the 60% reduction in incidence of postpartum haemorrhage described in the meta-analysis measuring the overall effect of active management. To show a reduction of at least 30% in the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage in the controlled cord traction arm—that is, an incidence of 4.9% or less in this arm, with α=0.05, 1−β=0.80, and a bilateral test, the study required 1990 women with vaginal deliveries in each group, totalling 3980 participants.

Given the expected proportion of women with a caesarean delivery in labour after randomisation (estimated at 5% to 10%), a higher number of women needed to be randomised to include the needed number of women with vaginal deliveries. The decision to stop recruitment was made by the independent data monitoring committee, which was able to access the electronic inclusion system to determine the real time cumulative number of randomised women and their mode of delivery.

This sample size provided a 70% statistical power to detect a reduction in the incidence of severe postpartum haemorrhage (defined by blood loss ≥1000 mL) from 2% to 1% or less of deliveries.

Randomisation

Randomisation took place after the women completed the form for participation, during labour, and before delivery. It was done centrally through an automated web-based system, which ensured allocation concealment. Allocation was stratified by centre and balanced in blocks of four.

Statistical analysis

We compared the two groups for main and secondary outcomes in an intention to treat analysis. The effects of controlled cord traction were expressed as mean differences (95% confidence intervals) for quantitative outcomes and as relative risks (95% confidence intervals) for categorical outcomes. To test the consistency of the primary outcome across centres, we used the Mantel-Haenszel homogeneity test. The incidence of each adverse event (cord rupture and uterine inversion) was expressed as a proportion, with binomial exact confidence intervals.

We carried out an analysis including women who had a caesarean delivery after randomisation (for a total of 2172 in the controlled cord traction arm and 2180 women in the standard placenta expulsion arm), for secondary outcomes available in these women (mean change in haemoglobin level, mean change in haematocrit measurement, postpartum transfusion, arterial embolisation, or emergency surgery).

A post hoc per protocol analysis was conducted among women who were managed in accordance with the protocol and the allocation—that is, those who had all the following procedures: prophylactic oxytocin administered after birth, cord clamping and cutting within two minutes, management of placenta expulsion in accordance with the allocation group (controlled cord traction or standard placenta expulsion), and blood collector bag left in place at least 15 minutes.

Analyses were carried out with Stata 10.1.

Results

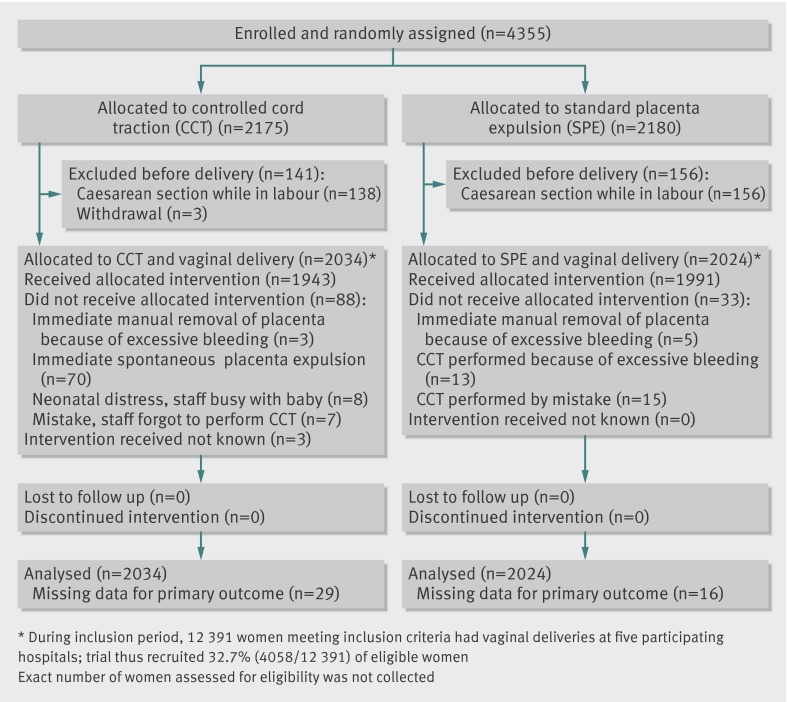

The trial was carried out in all five hospitals between 1 January 2010 and 31 January 2011. In all, 4355 women in labour were enrolled and randomly assigned. The figure shows the trial profile. After randomisation and before delivery, 294 (6.8%) women became ineligible because an intrapartum caesarean was performed, and three others declined to participate. Thus 4058 randomised participants delivered vaginally: 2034 assigned to controlled cord traction and 2024 to standard placenta expulsion. The two groups had similar baseline maternal and obstetric characteristics (table 1).

Trial flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women according to management of third stage of labour. Values are number with characteristic/number in group (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Controlled cord traction (n=2034) | Standard placenta expulsion (n=2024) |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital: | ||

| Port-Royal maternity hospital | 485/2034 (23.8) | 489/2024 (24.1) |

| Saint Vincent de Paul University hospital | 213/2034 (10.5) | 202/2024 (10.0) |

| Caen University hospital | 345/2034 (17.0) | 332/2024 (16.4) |

| Lille University hospital | 446/2034 (21.9) | 443/2024 (21.9) |

| Angers University hospital | 545/2034 (26.8) | 558/2024 (27.6) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 30.2 (5.2) (n=2034) | 30.0 (5.2) (n=2024) |

| French nationality | 1838/2000 (91.9) | 1814/1995 (90.9) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index | 22.8 (4.3) (n=2031) | 22.7 (4.1) (n=2017) |

| Nulliparous | 1074/2030 (52.9) | 1031/2010 (51.3) |

| Previous postpartum haemorrhage | 43/2030 (2.1) | 39/2010 (1.9) |

| Uterine scar | 132/2033 (6.5) | 120/2021 (5.9) |

| Mean (SD) prenatal haemoglobin (g/L) | 120 (10) (n=2005) | 120 (10) (n=1990) |

| Mean (SD) prenatal haematocrit (%) | 35.6 (1.0) (n=1952) | 35.5 (2.9) (n=1933) |

| Mean (SD) gestation at delivery (weeks) | 39.4 (1.2) (n=2034) | 39.4 (1.2) (n=2024) |

| Induction of labour | 381/2034 (18.7) | 406/2024 (20.1) |

| Epidural analgesia | 1975/2033 (97.1) | 1957/2023 (96.7) |

| Oxytocin during labour* | 1352/2033 (66.5) | 1362/2020 (67.4) |

| Instrumental delivery | 367/2034 (18.0) | 381/2024 (18.8) |

| Episiotomy | 597/2034 (29.3) | 586/2024 (29.0) |

| Perineal tear | 1036/2033 (51.0) | 1024/2024 (50.6) |

| Mean (SD) birth weight (g) | 3365 (428) (n=2032) | 3390 (433) (n=2022) |

| Birth weight ≥4000 g | 159/2032 (7.8) | 157/2022 (7.8) |

*First and second stage.

Table 2 details the management of the third stage of labour. Overall, both groups showed good adherence to the protocol. The figure shows the reasons for deviating from the allocated intervention.

Table 2.

Adherence to allocated intervention and other aspects of management of third stage of labour. Values are number with variable/number in group (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Variables | Controlled cord traction | Standard placenta expulsion |

|---|---|---|

| Prophylactic oxytocin within 2 minutes of birth | 1977/2029 (97.4) | 1961/2022 (97.0) |

| Cord clamping and cutting within 2 minutes of birth | 1933/2026 (95.4) | 1944/2019 (96.3) |

| Cord management according to protocol | 1943/2031 (95.7)* | 1991/2024 (98.4)* |

| Blood collector bag | 2016/2028 (99.4) | 2015 (2020 (99.7) |

| Mean (SD) duration of blood collection (min) | 27 (16) (n=1990) | 29 (16) (n=1987) |

| Blood collector bag in place ≥15 minutes | 1609/2002 (80.4) | 1717/1992 (86.2) |

*88 women in controlled cord traction arm and 33 in standard placenta expulsion arm did not receive allocated intervention (see figure).

Primary outcome data were collected for 4013 (98.9%) participants. The proportion of women with a measured postpartum blood loss of 500 mL or more at bag removal did not differ between the two groups (196/2005, 9.8% in the controlled cord traction group and 206/2008, 10.3% in the standard placenta expulsion group: relative risk 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.79 to 1.15) (table 3). This result showed no significant heterogeneity between centres (table 3). Similarly, the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage ≥1000 mL at bag removal did not differ between the two groups, nor did the mean measured blood loss at 15 minutes and at removal of the bag (table 3).

Table 3.

Trial outcomes. Values are number with outcome/number in group (percentage) unless stated otherwise

| Outcomes | Controlled cord traction | Standard placenta expulsion | Relative risk (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood loss ≥500 mL | 196/2005 (9.8) | 206/2008 (10.3) | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.15) | — |

| By hospital: | 0.31* | |||

| Port-Royal maternity hospital | 46/473 (9.7) | 37/482 (7.7) | 1.27 (0.84 to 1.92) | — |

| Saint Vincent de Paul University hospital | 20/199 (10.1) | 14/196 (7.1) | 1.41 (0.73 to 2.71) | — |

| Caen University hospital | 40/344 (11.6) | 49/330 (14.9) | 0.78 (0.53 to 1.16) | — |

| Lille University hospital | 38/445 (8.5) | 42/443 (9.5) | 0.90 (0.59 to 1.37) | — |

| Angers University hospital | 52/544 (9.6) | 64/557 (11.5) | 0.83 (0.59 to 1.18) | — |

| Blood loss ≥1000 mL | 34/2005 (1.7) | 37/2008 (1.8) | 0.92 (0.58 to 1.46) | — |

| Mean (SD) blood loss at 15 minutes (mL) | 163 (4) (n=2005) | 161 (4) (n=2001) | — | 1.7 (−8.8 to 12.2) |

| Mean (SD) total blood loss (mL) | 207 (5) (n=2005) | 217 (6) (n=2008) | — | −9.4 (−24.8 to 6.0) |

| Blood transfusion for postpartum haemorrhage | 12/2034 (0.6) | 9/2024 (0.4) | 1.33 (0.56 to 3.14) | — |

| Arterial embolisation or surgery for postpartum haemorrhage | 3/2034 (0.1) | 5/2024 (0.3) | 0.60 (0.14 to 2.49) | — |

| Mean (SD) peripartum change in haemoglobin (g/L)† | 86 (0.3) (n=1961) | 87 (0.3) (n=1953) | — | −0.2 (−1.0 to 0.7) |

| Mean (SD) peripartum change in haematocrit (%)‡ | 2.1 (0.1) (n=1904) | 2.2 (0.1) (n=1890) | — | −0.05 (−0.29 to 0.19) |

| Mean (SD) duration of third stage (min) | 5.5 (0.1) (n=2030) | 8.7 (0.1) (n=2020) | — | −3.26 (−3.62 to −2.90) |

| Third stage ≥15 minutes | 91/2030 (4.5) | 289/2020 (14.3) | 0.31 (0.25 to 0.39) | — |

| Manual removal of placenta | 85/2033 (4.2) | 123/2024 (6.1) | 0.69 (0.53 to 0.90) | — |

| Additional uterotonics after placenta delivery | 727/2030 (35.8) | 805/2024 (39.8) | 0.92 (0.83 to 0.97) | — |

| Maternal pain during third stage | 109/1892 (5.8) | 138/1868 (7.4) | 0.78 (0.61 to 0.99) | — |

| Cord rupture | 89/2034 (4.4) | 2/2024 (0.1) | 44.3 (10.9 to 179.6) | — |

| Uterine inversion | 0/2034 (0.0) | 0/2024 (0.0) | — | — |

*P for Mantel-Haenszel test of homogeneity across centres.

†Prepartum haemoglobin level measured within eighth month of gestation and arrival in labour ward in 1778 (90.7%) and 1760 (90.1%), at arrival in labour ward in 95 (4.8%) and 99 (5.1%), and between 5-7 months of gestation in 88 (4.5%) and 94 (4.8%), in controlled cord traction and standard placenta expulsion arms, respectively; postpartum haemoglobin level measured at postpartum day 2 in 1793 (91.4%) and 1787 (91.5%) and on another day between one and eight days in 168 (8.6%) and 166 (8.5%) in controlled cord traction and standard placenta expulsion arms, respectively.

‡Prepartum haematocrit measured within eighth month of gestation and arrival in labour ward in 1724 (90.5%) and 1707 (90.3%), at arrival in labour ward in 95 (5.0%) and 99 (5.2%), and between the 5-7 months of gestation in 85 (4.5%) and 84 (4.4%) in controlled cord traction and standard placenta expulsion groups, respectively; postpartum haematocrit measured at postpartum day 2 in 1737 (91.2%) and 1725 (91.3%) and on another day between one and eight days in 167 (8.8%) and 165 (8.7%) in controlled cord traction and standard placenta expulsion arms, respectively.

Outcome data related to blood count indicators before and after delivery were available for 1963/2034 (96.5%) women in the controlled cord traction group and 1953/2024 (96.5%) in the standard placenta expulsion group (at least one peripartum change in haemoglobin level or haemotocrit was available). Twenty women (11 in the controlled cord traction arm and nine in the standard placenta expulsion arm) had a transfusion before postpartum day 2 and were excluded from this analysis. The mean peripartum change in haemoglobin or haematocrit values did not differ significantly (table 3). The proportion of women with a peripartum decrease in haemoglobin concentration of 40 g/L or more did not differ between the two arms (2.1% (41/1961) in the controlled cord traction arm and 1.8% (35/1953) in the standard placenta expulsion arm: relative risk 1.17 (95% confidence interval 0.75 to 1.82).

Women in the controlled cord traction arm required fewer manual removals of the placenta than those in the standard placenta expulsion arm: relative risk 0.69 (95% confidence interval 0.53 to 0.90) (table 3). The third stage was shorter in the controlled cord traction arm.

No uterine inversion occurred among the 1943 women who had controlled cord traction (incidence 0.0%, one sided 97.5% confidence interval 0.0% to 0.18%). Cord rupture occurred in 89 (incidence 4.6%, 3.6% to 5.5%); 43 (48%) of these women required manual removal of the placenta. No other adverse events occurred in the two arms.

Women in the controlled cord traction arm reported a significantly lower intensity of pain and discomfort during the third stage than those in the standard placenta expulsion arm; they were less likely to have felt tired and anxious and to report a long duration of the third stage (table 4).

Table 4.

Women’s experience of third stage of labour according to management. Values are number with experience/number in group (percentage)

| Variables | Controlled cord traction | Standard placenta expulsion | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed forms | 1838/2034 (90.4) | 1844/2024 (91.2) | 0.41 |

| Felt tired: | |||

| Not at all | 466/1829 (25.5) | 426/1838 (23.2) | 0.017 |

| A little | 656/1829 (35.9) | 621/1838 (33.8) | |

| Moderately | 378/1829 (20.6) | 445/1838 (24.2) | |

| Very | 252/1829 (13.8) | 285/1838 (15.5) | |

| Extremely | 77/1829 (4.2) | 61/1838 (3.3) | |

| Felt anxious: | |||

| Not at all | 1191/1821 (65.4) | 1073/1821 (58.9) | <0.001 |

| A little | 398/1821 (21.9) | 475/1821 (26.1) | |

| Moderately | 154/1821 (8.5) | 168/1821 (9.2) | |

| Very | 59/1821 (3.2) | 94/1821 (5.2) | |

| Extremely | 19/1821 (1.0) | 11/1821 (0.6) | |

| Felt third stage was long: | |||

| Not at all | 1590/1830 (86.9) | 1451/1833 (79.2) | <0.001 |

| A little | 137/1830 (7.5) | 219/1833 (11.9) | |

| Moderately | 68/1830 (3.7) | 110/1833 (6.0) | |

| Very | 23/1830 (1.2) | 43/1833 (2.4) | |

| Extremely | 12/1830 (0.7) | 10/1833 (0.5) | |

| Felt satisfied: | |||

| Not at all | 4/1832 (0.2) | 3/1840 (0.2) | 0.21 |

| A little | 6/1832 (0.3) | 11/1840 (0.6) | |

| Moderately | 63/1832 (3.4) | 81/1840 (4.4) | |

| Very | 716/1832 (39.1) | 751/1840 (40.8) | |

| Extremely | 1043/1832 (57.0) | 994/1840 (54.0) | |

| Discomfort†: | |||

| ≤2 | 1408/1830 (76.9) | 1285/1834 (70.1) | <0.001 |

| 3-7 | 371/1830 (20.3) | 475/1834 (25.9) | |

| ≥8 | 51/1830 (2.8) | 74/1834 (4.0) | |

| Pain intensity‡: | |||

| ≤2 | 1475/1828 (80.7) | 1362/1837 (74.1) | <0.001 |

| 3-7 | 309/1828 (16.9) | 413/1837 (22.5) | |

| ≥8 | 44/1828 (2.4) | 62/1837 (3.4) |

*χ2 test.

†Graded from 0 (no discomfort) to 10.

‡Graded from 0 (no pain) to 10.

The per protocol analysis was conducted in 1437/1999 (71.9%) women in the controlled cord traction arm and 1574/1990 (79.1%) in the standard placenta expulsion arm. The proportion of women with a measured postpartum blood loss of 500 mL or more at bag removal did not differ between the two arms (11.7% (168/1431) in the controlled cord traction arm and 10.7% (168/1570) in the standard placenta expulsion arm): relative risk 1.10 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 1.34).

Finally, the results of the analysis including women who had a caesarean delivery after randomisation were similar to those of the main analysis (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large multicentre randomised trial, controlled cord traction as one component of the active management of the third stage of labour had no significant effect on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage. Controlled cord traction did, however, reduce the duration of the third stage and the need for manual removal of the placenta. Moreover, women in the controlled cord traction arm reported a significantly lower intensity of pain and discomfort as well as less fatigue and anxiety than women in the standard placenta expulsion arm.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This trial included a large population of pregnant women, with few exclusion criteria. Hence the results are likely to be generalisable to women with vaginal deliveries in similar contexts of care. Moreover, the adherence to the allocated intervention and other standardised aspects of third stage management was high, making it possible to isolate the effect of controlled cord traction.

It was not possible to blind this intervention as the procedures being tested required different actions by the attendants. The primary and main secondary outcomes (change in peripartum haemoglobin level and haematocrit) were, however, objective measures of postpartum blood loss as opposed to other definitions of postpartum haemorrhage based on visual estimation or interventions influenced by caregiver decisions. Although the quality of the controlled cord traction technique was not formally evaluated, a real difference in the management of placental expulsion between the two groups is likely, given the emphasis on the initial training. Moreover, the attendants in the two groups clearly reported different procedures, and the length of the third stage was significantly shorter and the incidence of cord rupture higher in the controlled cord traction group.

Comparison with other studies

Two small trials in the 1960s19 22 27 assessed the specific effects of controlled cord traction during the third stage. Both had important methodological weaknesses, including inadequate method of randomisation, visual estimation of blood loss for determining outcome measures, and limited sample sizes. Recently, a large randomised controlled trial conducted in eight low and middle income countries compared controlled cord traction with “hands-off” management of the third stage of labour.23 The results showed that the omission of controlled cord traction did not result in an increased risk of measured blood loss of 1000 mL or more. However, heterogeneity between centres in other components of third stage management (type of uterotonic used, combination with uterine massage), absence of report on the actual duration of blood loss measurement in each arm, and absence of outcomes based on blood counts, may limit the interpretation of the results. In addition, although it is of major importance to conduct research studies in low and middle income countries, the generalisability of the results for high income settings needs to be tested. Indeed, the characteristics of women, management of labour, resources, and organisation of care in the labour ward differ between low and high resource countries, and these differences may impact the risk and the characteristics of postpartum haemorrhage. Mechanisms of postpartum haemorrhage and effective preventive procedures may differ between settings. It is noteworthy that the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage ≥500 mL in the reference group of the previous controlled cord traction trial was about 30% higher than the incidence found in the current trial, which might indicate higher exposure to the risk of postpartum haemorrhage. For these reasons, our results provide valuable additional evidence that controlled cord traction is not an essential component of management of the third stage of labour for prevention of postpartum haemorrhage in high resource countries.

Implications for clinical practice

Cord rupture occurred in about 1 in 22 women who had controlled cord traction. This rate may at first seem notable. In most cases (52%), however, delivery of the placenta occurred without any extra intervention; and overall, the rate of manual removal of placenta was lower in women who had controlled cord traction. In consequence, cord rupture should not be considered an important adverse effect of controlled cord traction and does not imply manual removal of placenta.

The 30% reduction in the need for manual removal of placenta found in the controlled cord traction arm may provide a meaningful decrease in morbidity, considering the need for analgesia and antibiotics, separation of mother and baby, and the risk of infection associated with this intervention.28 However, we cannot exclude the possibility that such a difference may have been less important (or even not significant) if the French policy was more conservative, allowing a duration of third stage labour greater than 30 minutes before manually removing the placenta, in particular in the standard placenta expulsion arm. Our finding of a lower risk of manual removal of placenta when its expulsion is managed with controlled cord traction contrasts with the conclusions of the trial cited above.29 In this study, however, manual removal of placenta was performed in less than 1% of deliveries in both arms, which is low compared with previous reports from high resource countries30 31 and may actually illustrate the variations in policies for the management of the third stage of labour between settings.32 Our trial also showed that controlled cord traction significantly reduced the duration of the third stage. This result may have implications for optimising the organisation of postpartum surveillance and care, in particular in hospitals where the number of midwives or birth attendants in labour wards is limited. In addition, the shorter third stage and lesser need for manual removal of placenta associated with controlled cord traction are likely to be the main reasons why women reported a better experience of the third stage of labour in the controlled cord traction arm, although we cannot exclude a patient preference bias as the study was not blinded.

Another controversial aspect of the management of the third stage of labour is the timing of cord clamping. Recent results from a trial conducted in Sweden showed that, even in a region with low prevalence of iron deficiency, delayed cord clamping reduced the prevalence of neonatal anaemia and improved iron status at 4 months of age in babies born at term,33 confirming the findings of previous trials conducted in low and middle income populations.34 Controlled cord traction, as it is classically performed, is not compatible with delayed cord clamping. Our finding that controlled cord traction has no significant effect on maternal postpartum haemorrhage constitutes reassuring information for clinicians willing to implement a policy of delayed cord clamping, from both maternal and neonatal perspectives.

In a high resource setting, the use of controlled cord traction for the management of placental expulsion has no significant effect on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and other markers of postpartum blood loss. There is therefore no evidence to recommend routine controlled cord traction for the management of placental expulsion to prevent postpartum haemorrhage.

What is already known on this topic

Active management of the third stage of labour includes administering uterotonic drugs immediately after birth and controlled cord traction (CCT), recommended to prevent postpartum haemorrhage

The management of third stage of labour without CCT does not increase the risk of severe postpartum in low and middle income countries, and therefore the procedure could be omitted in non-hospital settings

The impact of CCT on incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and other characteristics of third stage labour is unknown in the context of high resource settings

What this study adds

In a high resource setting the use of CCT for the management of placental expulsion had no significant effect on the incidence of postpartum haemorrhage and other markers of postpartum blood loss

CCT is, however, safe, reduces the length of third stage labour and the need for manual removal of placenta, and results in a better experience of the third stage of labour for women

The full trial protocol can be accessed at www.u953.idf.inserm.fr/page.asp?page=5211. We thank the independent data monitoring committee chaired by JM Treluyer from the Unité de Recherche Clinique Paris Centre; the women who participated in the trial; the staff from the participating maternity units for including women, and the members of the TRACOR Study Group (see supplementary file). Inserm Unit 953 has received a grant from the Bettencourt Foundation (Coups d’élan pour la Recherche française) in support of its research activities.

Contributors: CD-T participated in the design of the study, obtained funding, participated in the central monitoring of data collection, supervised the cleaning, analysis, and interpretation of the data and the drafting and revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. She had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. LS participated in the design of the study, supervised the inclusion of women and the running of the trial in his hospital, participated in the revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. FM participated in the central monitoring of data collection, supervised the cleaning of the data, conducted the analysis, participated in the drafting and the revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. EC participated in the design of the study, supervised the inclusion of women and the running of the trial in his hospital, participated in the revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. DV participated in the design of the study, supervised the inclusion of women and the running of the trial in her hospital, participated in the revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. JL participated in the design of the study, supervised the inclusion of women and the running of the trial in his hospital, participated in the revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. FG is the principal investigator of the trial; he participated in the design of the study, obtained funding, participated in the central monitoring of data collection, supervised the cleaning, analysis, and interpretation of the data and the drafting and revision of the paper, and has seen and approved the final version. He had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CD-T and FG are guarantors for the paper.

Funding: The TRACOR trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health under its clinical research hospital programme (contract No P081206). The Ministry of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, and the preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript or in the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: support from the French Ministry of Health for the submitted work; LS was a board member and carried out consultancy work and lecturer for Ferring; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Paris-Ile de France III Committee for the Protection of Research Subjects (Ethics Committee) in September 2009.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f1541

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Members of the TRACOR Study Group

References

- 1.Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:133.e1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang WH, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle MH, Macfarlane A. Incidence of severe pre-eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis as a surrogate marker for severe maternal morbidity in a European population-based study: the MOMS-B survey. BJOG 2005;112:89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zwart J, Richters J, Öry F, de Vries J, Bloermenkamp K, van Roosmalen J. Severe maternal morbidity during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based study of 371 000 pregnancies. BJOG 2008;115:842-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brace V, Penney G, Hall M. Quantifying severe maternal morbidity: a Scottish population study. BJOG 2004;111:481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyelese Y, Ananth CV. Postpartum hemorrhage: epidemiology, risk factors, and causes. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2010;53:147-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Recommendations for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage. WHO. 2007. http://apps.who.int/rhl/effective_practice_and_organizing_care/guideline_pphprevention_fawoleb/en/index.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Begley CM. A comparison of ‘active’ and ‘physiological’ management of the third stage of labour. Midwifery 1990;6:3-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan GQ, John IS, Wani S, Doherty T, Sibai BM. Controlled cord traction versus minimal intervention techniques in delivery of the placenta: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:770-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prendiville WJ, Harding JE, Elbourne DR, Stirrat GM. The Bristol third stage trial: active versus physiological management of third stage of labour. BMJ 1988;297:1295-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers J, Wood J, McCandlish R, Ayers S, Truesdale A, Elbourne D. Active versus expectant management of third stage of labour: the Hinchingbrooke randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1998;351:693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(11):CD007412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lalonde A, Daviss BA, Acosta A, Herschderfer K. Postpartum hemorrhage today: ICM/FIGO initiative 2004-2006. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;94:243-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage. WHO. 2007. www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/publications/WHORecommendationsforPPHaemorrhage.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Goffinet F, Mercier F, Teyssier V, Pierre F, Dreyfus M, Mignon A, et al. [Postpartum haemorrhage: recommendations for clinical practice by the French College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (December 2004)]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2005;33:268-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leduc D, Senikas V, Lalonde AB, Ballerman C, Biringer A, Delaney M, et al. Active management of the third stage of labour: prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009;31:980-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Green Top Guideline No 52. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage.May 2009. www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/GT52PostpartumHaemorrhage0411.pdf.

- 18.Cotten A, Ness A, Tolosa J. Prophylactic use of oxytocin for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(2):CD001808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonham DG. Intramuscular oxytocics and cord traction in third state of labour. BMJ 1963;2:1620-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winter C, Macfarlane A, Deneux-Tharaux C, Zhang WH, Alexander S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Variations in policies for management of the third stage of labour and the immediate management of postpartum haemorrhage in Europe. BJOG 2007;114:845-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goffinet F. Inversion uterine. In: Cabrol D, Pons JC, Goffinet F, eds. Traite d’obstetrique. Flammarion Medecine-Sciences; 2003:941-4.

- 22.Kemp J. A review of cord traction in the third stage of labour from 1963 to 1969. Med J Aust 1971;1:899-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulmezoglu AM, Lumbiganon P, Landoulsi S, Widmer M, Abdel-Aleem H, Festin M, et al. Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012;379:1721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang WH, Deneux-Tharaux C, Brocklehurst P, Juszczak E, Joslin M, Alexander S. Effect of a collector bag for measurement of postpartum blood loss after vaginal delivery: cluster randomised trial in 13 European countries. BMJ 2010;340:c293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rath WH. Postpartum hemorrhage—update on problems of definitions and diagnosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deneux-Tharaux C, Dupont C, Colin C, Rabilloud M, Touzet S, Lansac J, et al. Multifaceted intervention to decrease the rate of severe postpartum haemorrhage: the PITHAGORE6 cluster-randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2010;117:1278-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Althabe F, Bergel E, Buekens P, Sosa C, Belizan JM. Controlled cord traction in the third stage of labor. Systematic review. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;94(S2):S126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chongsomchai C, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Prophylactic antibiotics for manual removal of retained placenta in vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(2):CD004904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulmezoglu AM, Lumbiganon P, Landoulsi S, Widmer M, Abdel-Aleem H, Festin M, et al. Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012;379:1721-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung WM, Hawkes A, Ibish S, Weeks AD. The retained placenta: historical and geographical rate variations. J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;31:37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weeks AD. The retained placenta. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2008;22:1103-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deneux-Tharaux C, Macfarlane A, Winter C, Zhang WH, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle MH. Policies for manual removal of placenta at vaginal delivery: variations in timing within Europe. BJOG 2009;116:119-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson O, Hellstrom-Westas L, Andersson D, Domellof M. Effect of delayed versus early umbilical cord clamping on neonatal outcomes and iron status at 4 months: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2011;343:d7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutton EK, Hassan ES. Late vs early clamping of the umbilical cord in full-term neonates: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. JAMA 2007;297:1241-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Members of the TRACOR Study Group