Abstract

Objective To assess the association between obstetricians’ years of experience after training and the maternal complications of their patients during their first 40 years of post-residency practice.

Design Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting Obstetrical discharges from acute care hospitals in Florida and New York between academic years 1992 and 2009.

Population 6 704 311 deliveries performed by 5175 obstetricians.

Main outcome measure Three composite measures of maternal complication rates per physician year from vaginal and cesarean births separately and combined, adjusted for secular trends.

Results Obstetricians’ maternal complication rates declined during the first three decades after completion of residency. The improvement was largest in the first decade and diminished thereafter. For all deliveries, the change was −0.21 (95% confidence interval −0.23 to −0.19) percentage points per year in the first decade, −0.11 (−0.13 to −0.09) percentage points per year in the second decade, and −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.01) percentage points in the third decade (P<0.001 for second to first decade comparison; P=0.001 for third to second decade comparison). The patterns were comparable for cesarean deliveries and vaginal deliveries and across several sensitivity checks.

Conclusions Among obstetricians practicing in Florida and New York, those with more years of experience had fewer maternal complications. This association persisted over the first three decades of practice but diminished in magnitude.

Introduction

How does a physician’s clinical performance, as measured by patients’ outcomes, change over the course of a career? Intuitively, one might expect additional experience to improve performance early on, as physicians ascend a learning curve. In practice, patients, referring physicians, and health systems routinely seek out physicians with more experience because they are believed to perform better.

The experience-performance relation for physicians is not well understood, however, and the evidence is not well developed, partly because the potential underlying causal mechanisms are complex and difficult to observe. Physicians may improve by treating additional cases (“learning by doing”) or by observing other clinicians’ actions (“learning by watching”).1 Experience can be conceptualized and measured in multiple ways, such as by cumulative clinical volume over a career or by years of practice. Quantifying performance can likewise be problematic, as standards of care change over time and outcomes are affected by changes in patient mix as well as physicians’ experience. Moreover, the experience-performance relation might differ across settings and over the course of a career; as physicians near the end of their careers, performance might decline. That the results of existing studies vary greatly is thus not surprising.2

In this study, we examined the association between obstetricians’ years of experience after training and their performance, measured as a rate of maternal complications per physician year, during their first 40 years of post-residency practice.

Methods

Patients and physicians

We used data from Florida and New York all-payer hospital discharge databases for calendar years 1992 through 2010, covering all deliveries at all non-federal acute care hospitals. We selected these states because their data contain identifiers of physicians in addition to information typically found in discharge databases, such as patients’ demographics and codes for diagnosis and procedure. We identified cesarean deliveries by an ICD-9 (international classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification) procedure code of 74 in any procedure field. We identified vaginal deliveries by diagnosis codes of 650 or 640.0x through 676.9x (where x is 1 or 2) in the principal diagnosis field and no indication of a cesarean delivery. We augmented the discharge data with information on each physician’s residency program, including specialty and graduation year, from the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile.

Because physicians typically graduate from residency programs around 1 July, we measured time according to an academic year calendar (starting 1 July and ending 30 June); we included deliveries in the 18 academic years between 1 July 1992 and 30 June 2010. We excluded deliveries if the delivering clinician did not have a valid state license number, was not identified in the Physician Masterfile as having completed an obstetrics-gynecology residency (typically reflecting delivery by a family practitioner or midwife), completed residency training before 1970 (to ensure that all deliveries were performed by a physician with no more than 40 years of experience), or was observed in only a single academic year.

Outcomes

We assessed physicians’ performance by using two measures of maternal complication. For cesarean deliveries, the measure included infection, hemorrhage, and other major operative and thrombotic complications; for vaginal deliveries, the measure included hemorrhage, severe laceration, infection, and thrombotic complications (appendix table A). We also examined maternal complications for all deliveries together by using a combination of these two measures. To better understand the potential role of changes in patterns of practice over the course of a physician’s career on performance, we examined secondary outcomes of physicians’ cesarean delivery rate, mean number of maternal comorbidities per patient, and total delivery volume. The unit of analysis was the physician year, and we measured all outcomes as rates per physician year.

Statistical analysis

We did a longitudinal analysis of the association between physicians’ experience, measured as years since completing an obstetrics and gynecology residency, and performance, measured by the number of maternal complications per year of practice, during the first 40 years of post-residency practice.

We explored two alternative specifications for years of experience. Firstly, to provide a fine grained picture, we specified years of experience as a set of 39 indicator variables and then plotted adjusted predictions and associated confidence intervals of the outcome for each year of experience. We used Sidak’s method to adjust the confidence intervals for multiple comparisons.3 Alternatively, to assess parsimoniously how the relation changed over years of experience, we specified experience as a set of four linear splines with distinct slopes for each decade of experience and then calculated average marginal effects of the impact of a one year increase in experience on outcomes in their native scale. We calculated confidence intervals for average marginal effects by the delta method.4

In unadjusted analyses, we estimated negative binomial regression models with annual delivery volume as the exposure to ensure that the model accounted for differences in delivery volume across physician years. Standard errors were robust to heteroskedasticity and also accounted for repeated observations per physician.

In adjusted analyses, we estimated negative binomial regression models that controlled for patient level and physician level characteristics and included a random effect for physician. Patient covariates, which were collapsed and measured as means per physician year, included age, race/ethnicity, having Medicaid or no insurance, weekend admission, and 31 maternal comorbidities (including previous cesarean delivery, fetal malpresentation, severe hypertension, multiple gestation, antepartum bleeding, herpes, macrosomia, unengaged head, maternal soft tissue disorder, preterm labor, congenital anomalies, oligohydramnios, and polyhydramnios (table 1).5 6 7 Physicians’ characteristics included state (Florida versus New York), secular trend (modeled as a set of indicator variables for calendar year)5, annual cesarean delivery rate, and total annual number of deliveries (as the exposure).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Characteristic | All (n=6 704 311) | Cesarean delivery (n=2 013 575) | Vaginal delivery (n=4 690 736) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: | |||

| ≤20 years | 903 890 (13.5) | 189 095 (9.4) | 714 795 (15.2) |

| 21-25 years | 1 538 276 (23.0) | 386 569 (19.2) | 1 151 707 (24.6) |

| 26-30 years | 1 841 457 (27.5) | 541 942 (26.9) | 1 299 515 (27.7) |

| 31-35 years | 1 579 850 (23.6) | 544 668 (27.1) | 1 035 182 (22.1) |

| ≥35 years | 840 838 (12.5) | 351 301 (17.4) | 489 537 (10.4) |

| Race/ethnicity: | |||

| Not non-Hispanic white | 3 112 223 (46.4) | 949 294 (47.1) | 2 162 929 (46.1) |

| Missing race/ethnicity | 238 822 (3.6) | 64 333 (3.2) | 174 489 (3.7) |

| Medicaid or no insurance | 3 032 889 (45.2) | 827 235 (41.1) | 2 205 654 (47.0) |

| Admitted on Saturday or Sunday | 1 368 994 (20.4) | 299 163 (14.9) | 1 069 831 (22.8) |

| Previous cesarean section | 949 068 (14.2) | 784 086 (38.9) | 164 982 (3.5) |

| Comorbidities: | |||

| Fetal malpresentation | 425 716 (6.4) | 335 754 (16.7) | 89 962 (1.9) |

| Antepartum bleeding | 116 048 (1.7) | 81 160 (4.0) | 34 888 (0.7) |

| Herpes, HIV, hepatitis, human papillomavirus, other viral illnesses | 101 763 (1.5) | 48 653 (2.4) | 53 110 (1.1) |

| Severe hypertension | 74 699 (1.1) | 51 755 (2.6) | 22 944 (0.5) |

| Uterine scar unrelated to cesarean section | 13 144 (0.2) | 11 812 (0.6) | 1332 (0.0) |

| Multiple gestation | 87 737 (1.3) | 61 041 (3.0) | 26 696 (0.6) |

| Macrosomia | 171 383 (2.6) | 106 866 (5.3) | 64 517 (1.4) |

| Unengaged fetal head | 102 840 (1.5) | 98 601 (4.9) | 4239 (0.1) |

| Maternal soft tissue disorder | 198 694 (3.0) | 138 569 (6.9) | 60 125 (1.3) |

| Other types of hypertension | 431 820 (6.4) | 189 631 (9.4) | 242 189 (5.2) |

| Preterm gestation | 480 502 (7.2) | 197 689 (9.8) | 282 813 (6.0) |

| Congenital fetal central nervous system anomaly or chromosomal abnormality | 5910 (0.1) | 3254 (0.2) | 2656 (0.1) |

| Asthma | 137 057 (2.0) | 52 428 (2.6) | 84 629 (1.8) |

| Maternal renal abnormality | 8784 (0.1) | 3577 (0.2) | 5207 (0.1) |

| Maternal liver abnormality | 6356 (0.1) | 2240 (0.1) | 4116 (0.1) |

| Diabetes or abnormal glucose tolerance | 47 483 (0.7) | 18 879 (0.9) | 28 604 (0.6) |

| Maternal thyroid abnormality | 100 301 (1.5) | 40 181 (2.0) | 60 120 (1.3) |

| Maternal substance misuse | 19 673 (0.3) | 5625 (0.3) | 14 048 (0.3) |

| Maternal mental disorder | 158 262 (2.4) | 53 754 (2.7) | 104 508 (2.2) |

| Maternal congenital and other heart disease | 93 040 (1.4) | 33 735 (1.7) | 59 305 (1.3) |

| Isoimmunization | 127 330 (1.9) | 38 594 (1.9) | 88 736 (1.9) |

| Intrauterine fetal demise | 2894 (0.0) | 638 (0.0) | 2256 (0.1) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 98 538 (1.5) | 47 359 (2.4) | 51 179 (1.1) |

| Oligohydramnios | 42 687 (0.6) | 24 372 (1.2) | 18 315 (0.4) |

| Polyhydramnios | 215 045 (3.2) | 92 708 (4.6) | 122 337 (2.6) |

| Ruptured membrane >24 hours | 105 478 (1.6) | 38 186 (1.9) | 67 292 (1.4) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 120 616 (1.8) | 65 156 (3.2) | 55 460 (1.2) |

| Other maternal infection | 70 929 (1.1) | 25 155 (1.2) | 45 774 (1.0) |

| Uterine rupture | 4351 (0.1) | 3781 (0.2) | 570 (0.0) |

| Maternal obesity | 59 413 (0.9) | 37 293 (1.9) | 22 120 (0.5) |

For the practice pattern outcomes, we modeled the annual cesarean rate by using negative binomial regression with delivery volume as the exposure. We modeled total annual delivery volume and mean number of maternal comorbidities per patient with linear regression. These models controlled for state and secular trend and used robust standard errors that accounted for clustering.

An important analytic concern is “survivor bias,” which could inflate the association between experience and performance. Poorly performing physicians might be more likely to stop performing deliveries as they practiced longer, making it seem that more experience leads to better outcomes when in fact worse outcomes lead to less experience. We therefore repeated all analyses on the subset of physicians who performed any deliveries in academic year 2009.

We used two tailed tests with P<0.05 to establish statistical significance. We used Stata version 12.1 for analyses.

Results

During 1992-2010, 8 500 303 deliveries took place in Florida and New York, of which 7 337 250 (86%) were performed by physicians with valid state license numbers who completed obstetrics and gynecology residencies and 6 968 506 (82%) were performed in the 18 academic years between July 1 1992 and June 30 2010. After exclusion of physicians who finished their residency before 1970 or who were observed in only a single year, 6 704 311 (79%) deliveries were performed by 5175 physicians. The analytic dataset consisted of 54 736 physician year observations (table 2). We repeated all analyses on the subset of 37 354 physician year observations from 3044 (59%) physicians who performed deliveries through academic year 2009 as a robustness check of survivor bias.

Table 2.

Sample descriptive statistics at physician year and physician levels. Values are numbers (percentages)

| Statistic | Physician years (n=54 736) | Physicians (n=5175) |

|---|---|---|

| State: | ||

| Florida | 19 999 (36.5) | 1945 (37.6) |

| New York | 34 737 (63.5) | 3230 (62.4) |

| Sex: | ||

| Male | 34 817 (63.6) | 2973 (57.5) |

| Female | 19 919 (36.4) | 2202 (42.6) |

| Specialty: | ||

| Obstetrics-gynecology | 51 772 (94.6) | 4898 (94.7) |

| Maternal-fetal medicine | 2964 (5.4) | 277 (5.4) |

| Medical school location: | ||

| United States or Canada | 39 177 (71.6) | 3784 (73.1) |

| Other | 15 559 (28.4) | 1391 (26.9) |

| Practice duration: | ||

| No deliveries in academic year 2009 | 17 382 (31.8) | 2131 (41.2) |

| ≥1 delivery in academic year 2009 | 37 354 (68.2) | 3044 (58.8) |

| Time since obstetrics-gynecology residency completion: | ||

| 1-10 years | 23 033 (42.1) | — |

| 11-20 years | 19 350 (35.4) | — |

| 21-30 years | 10 732 (19.6) | — |

| 31-40 years | 1621 (3.0) | — |

| Obstetrics-gynecology residency completion year: | ||

| 1970-79 | — | 840 (16.2) |

| 1980-89 | — | 1402 (27.1) |

| 1990-99 | — | 1751 (33.8) |

| 2000-08 | — | 1182 (22.8) |

| Duration in sample: | ||

| 2-5 years | — | 1273 (24.6) |

| 6-10 years | — | 1314 (25.4) |

| 11-15 years | — | 1193 (23.1) |

| 16-18 years | — | 1395 (27.0) |

Column percentages may not sum to 100 owing to rounding.

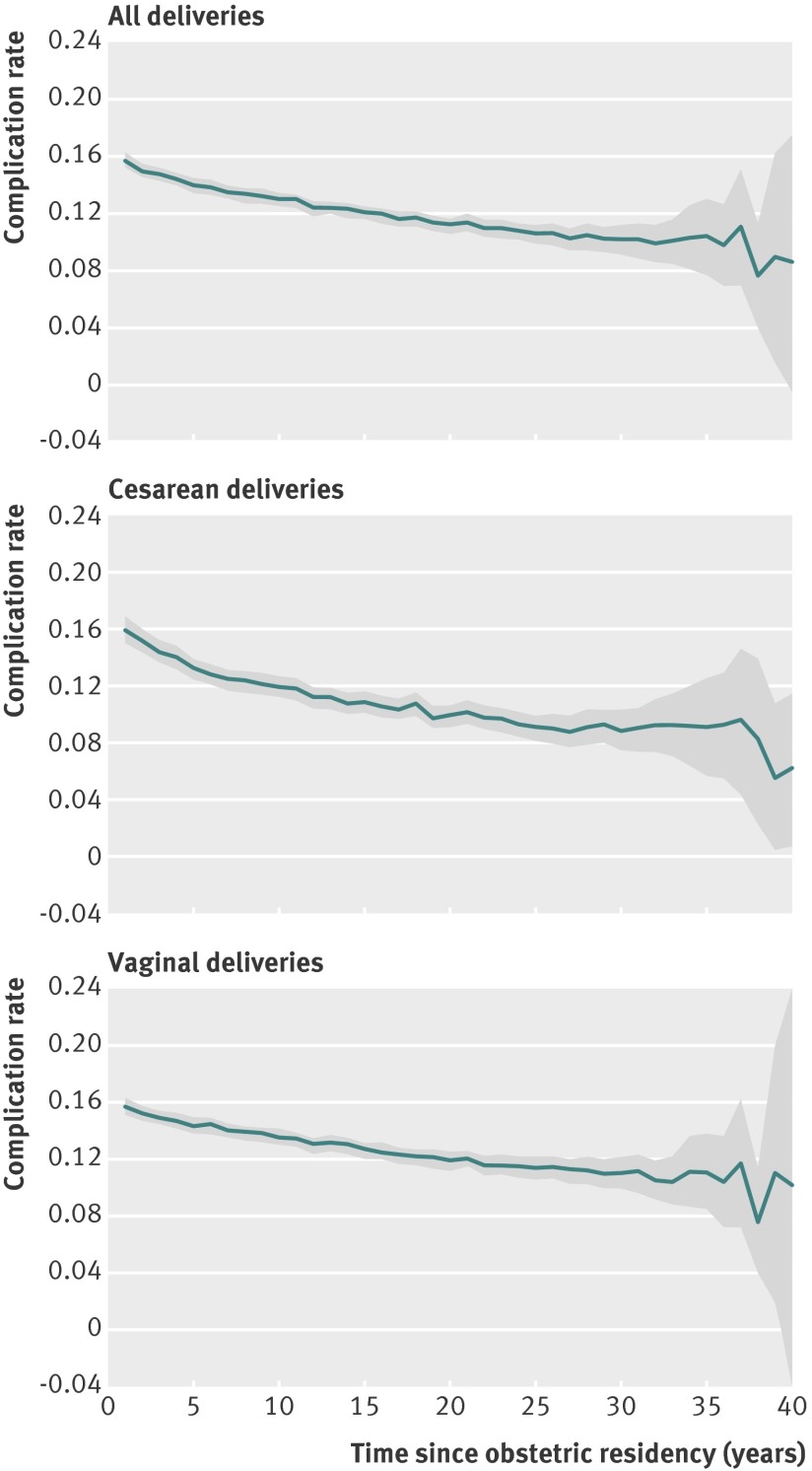

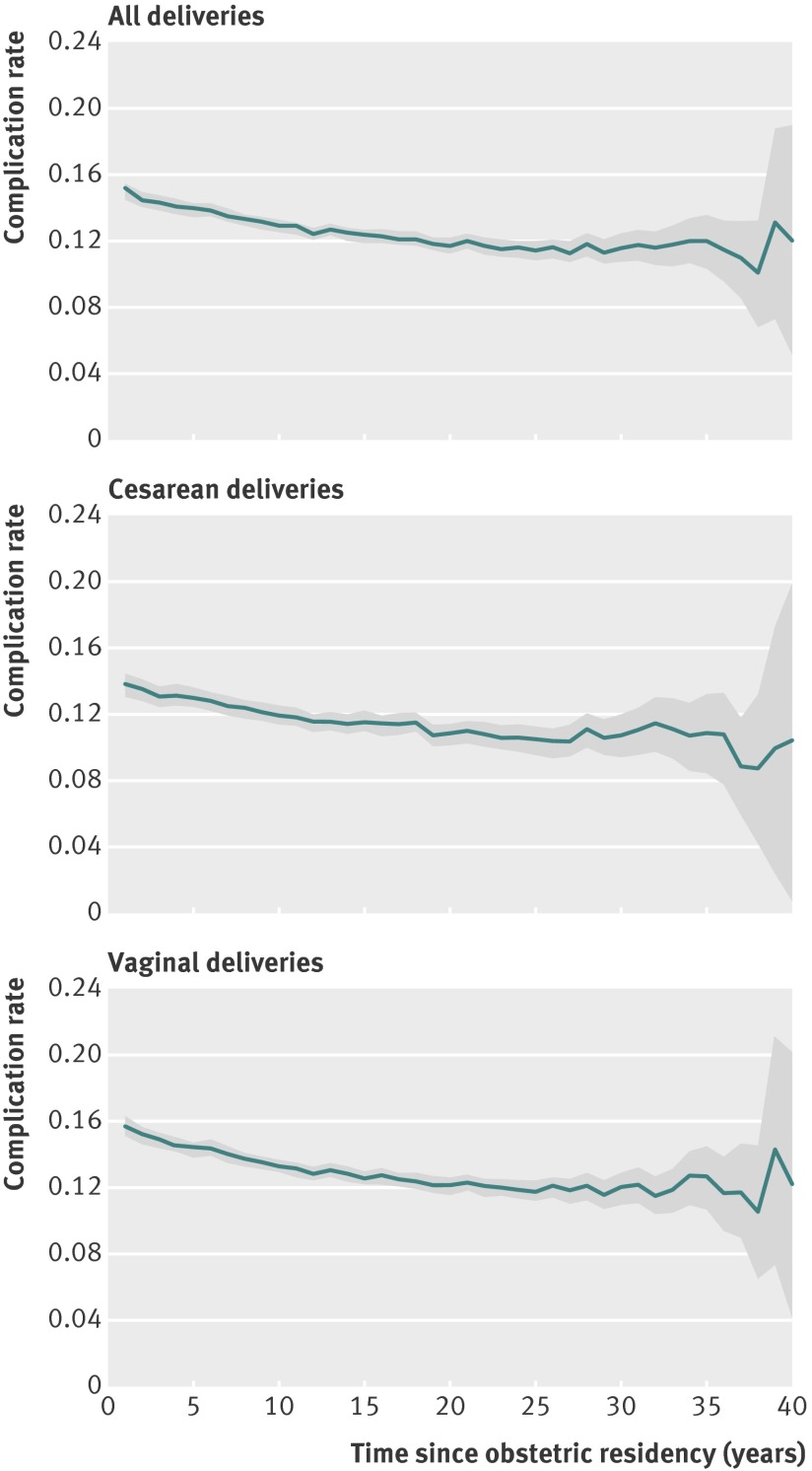

Figure 1 depicts trends in unadjusted, annual, physician level maternal complication rates for all deliveries, cesarean deliveries, and vaginal deliveries based on the full sample of all physicians. As physicians gained experience, performance improved for all three outcomes. The largest changes occurred soon after completion of residency, and improvement tapered off later in physicians’ careers. The observed trends in complication rates were similar when we adjusted for patients’ and physicians’ characteristics and a physician random effect (fig 2), as well as when we limited the sample to physicians who performed deliveries through academic year 2009 (appendix figures A and B).

Fig 1 Unadjusted annual maternal complication rates (with 95% confidence areas) by physician years of experience for all, cesarean, and vaginal deliveries. Estimates were generated from negative binomial regression. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors also accounted for repeated observations per physician. Confidence areas were further adjusted for multiple comparisons with Sidak’s method

Fig 2 Adjusted annual maternal complication rates (with 95% confidence areas) by physicians’ years of experience for all, cesarean, and vaginal deliveries. Estimates were generated from negative binomial regression models that controlled for state, secular trend, physicians’ annual cesarean delivery rate and total number of deliveries, patients’ comorbidities, demographics, weekend admission, and a physician level random effect. Confidence areas were further adjusted for multiple comparisons with Sidak’s method

Results from regressions in which years of experience were specified as linear splines also indicate that physicians’ performance improved over the three decades after training. Based on the sample of all physicians, the adjusted maternal complication rate in the first year after residency was 15.0%. The adjusted maternal complication rate changed during a physician’s first decade of practice by −0.21 (95% confidence interval −0.23 to −0.19) percentage points per year, during the second decade by −0.11 (−0.13 to −0.09) percentage points per year, and during the third decade by −0.05 (−0.08 to −0.01) percentage points per year (P<0.001 for second to first decade comparison; P=0.001 for third to second decade comparison).

The improvements were similar in the cesarean delivery sample and the vaginal delivery sample. Among cesarean deliveries, maternal complications started at 13.7%; each year, they changed by an average of −0.19 (−0.23 to −0.16) percentage points during the first decade, by −0.11 (−0.14 to −0.08) percentage points during the second decade, and by −0.04 (−0.09 to 0.01) percentage points during the third decade (P<0.001 for second to first decade comparison; P=0.02 for third to second decade comparison). Among vaginal deliveries, starting at a complication rate of 15.6%, the average annual change was −0.23 (−0.25 to −0.20) percentage points during the first decade, −0.11 (−0.14 to −0.09) percentage points during the second decade, and −0.04 (−0.07 to −0.01) percentage points during the third decade (P<0.001 for second to first decade comparison; P=0.001 for third to second decade comparison).

The results were consistent across various specifications (appendix table B). Across all three samples, the unadjusted regressions yielded similar patterns of results, although the estimated reductions in maternal comorbidities were somewhat larger. Moreover, the results from both sets of models were similar when we limited the sample to physicians who performed deliveries through academic year 2009.

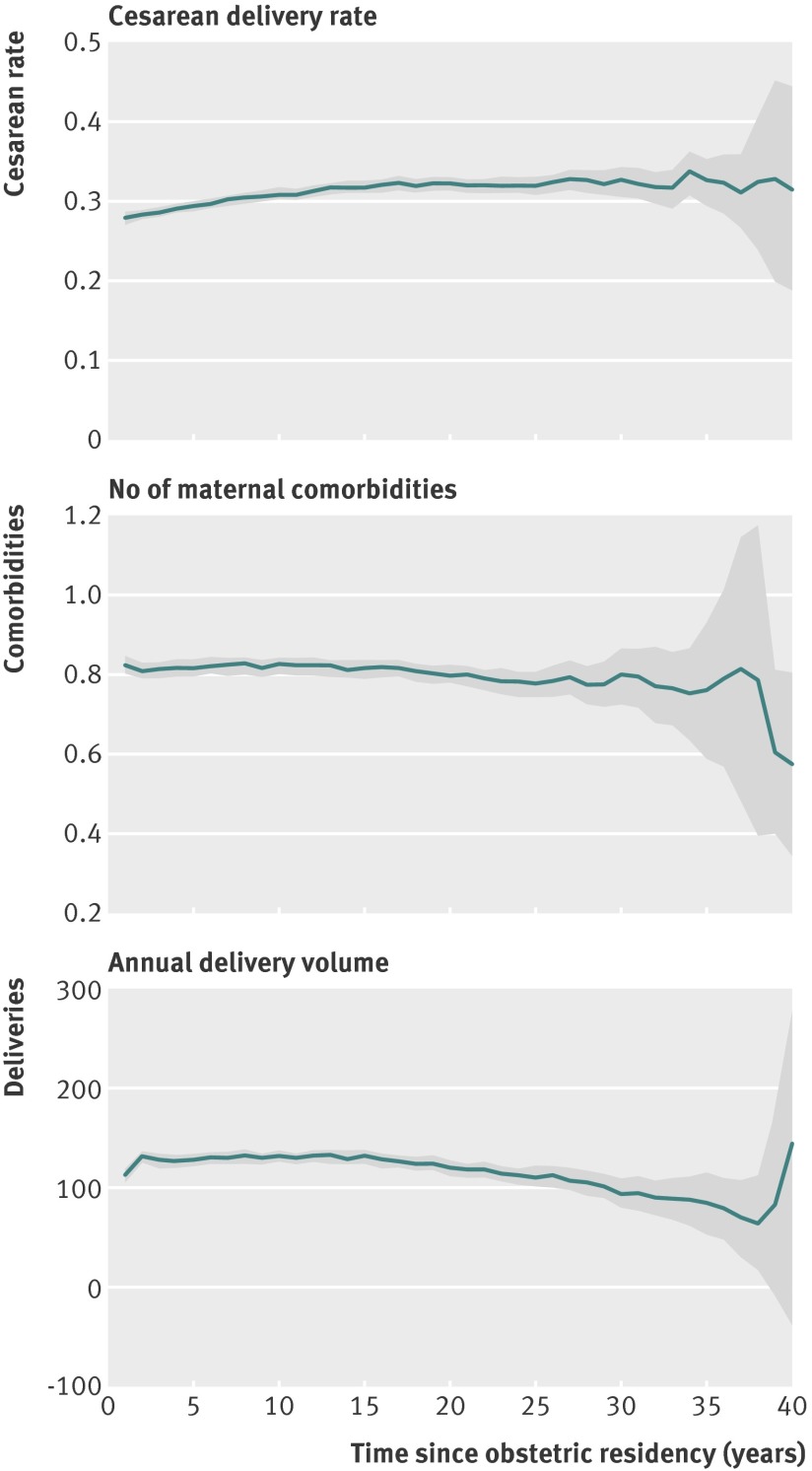

In contrast to the continuous improvement in outcomes, physicians’ delivery practice patterns seem to have changed little over their careers (fig 3). Physician specific cesarean delivery rates began at around 30% after residency and increased slightly. Physicians’ average number of comorbidities per patient started at 0.83 and stayed flat. Total volume started at 112 deliveries per year, increased by 1.2 (95% confidence interval 0.1 to 1.8) deliveries per year in the first decade, and then decreased by 1.2 (0.6 to 1.7), 2.3 (1.5 to 3.1), and 3.3 (0.6 to 6.1) deliveries per year in the subsequent decades.

Fig 3 Physicians’ practice patterns by years of experience: adjusted outcomes with 95% confidence areas. Estimates were generated from negative binomial (cesarean delivery rate) or linear (comorbidity and delivery volume) regression with adjustment for state and secular trend. Cesarean delivery rate model also controlled for total number of deliveries per year. Heteroskedasticity robust standard errors accounted for repeated observations per physician. Confidence areas were further adjusted for multiple comparisons with Sidak’s method

Discussion

The results of this study show that the clinical performance of obstetricians, as measured by maternal complications, improved with years of experience. This improvement was steepest in a physician’s first decade of practice after completion of residency; it tapered off but remained significant through the second and third decades of practice. These effects are large given the duration of the cumulative exposure. After a decade of experience, for example, an obstetrician is expected to have a maternal complication rate that is roughly 2 percentage points lower than a newly trained obstetrician, which is sizeable compared with the predicted 15% complication rate in the first year. A second decade of experience is expected to confer an additional 1 percentage point reduction, and a third decade further lowers complications by about 0.5 percentage points. These results were consistent whether we examined all deliveries together or vaginal and cesarean deliveries separately, whether we included all obstetricians or only those who did not leave practice before the end of the study period, and whether we controlled for patients’ and physicians’ characteristics or not. Intuition suggests that performance ought to improve with experience, and greater experience is often cited as a reason to select one physician over another. However, past research has shown that performance improves with experience primarily when physicians first perform a procedure,8 9 10 11 if at all,12 and that performance degrades as physicians near the end of their careers.2 13 14 Here we have shown that, in the context of obstetrics, the observed effect of experience is substantial and persistent but diminishes over time.

We chose to examine obstetric care for several reasons: complications are more directly attributable to a single physician than in many other clinical areas; maternal patients are typically young and healthy, with fewer risk factors to account for when comparing outcomes across physicians; the practice of obstetrics, although constantly evolving, has focused over several decades on a very limited set of procedures, suggesting that the effects of experience would be more visible than in fields in which new technologies have changed the treatment mix; and we are aware of no other studies of learning curves in obstetrical care, one of the most common reasons for admission to hospital.

Possible explanations

Why such sustained improvement in performance occurs is not clear from our results. What does an obstetrician with, say, 15 years of experience know or do differently from a peer with five, 10, or even 14 years of experience? Although maternal complications were decreasing steadily during our study period,5 we accounted for this secular trend in our analysis. Better performing physicians probably stay in practice longer, but our results were robust when we limited analyses to physicians still performing deliveries in the last year of data. More experienced physicians might attract patients who are healthier in important ways, but we found no evidence of substantive changes in physicians’ mean number of maternal comorbidities per patient over the first 40 years of their careers—nor did we find any substantive changes in physicians’ cesarean section delivery rates or annual delivery volume over the same time period. Of course, we cannot rule out the possibility of unmeasured confounders correlated with both physicians’ experience and patients’ outcomes, including the possibility that maternal complications are coded more accurately (and thus more frequently) for less experienced physicians.

We think that these results more likely reflect a continued increase in obstetricians’ technical skill in performing cesarean and vaginal deliveries over three decades. This is a much longer timeframe for sustained improvement than others have found, even for relatively complex surgeries such as prostatectomy and heart surgery.8 9 10 11 12 Subsequent decline in technical skill might also explain the degradation in outcomes starting around 30 years after residency, as has been found in some other settings.2 13 14 Maternal complications may decline with experience for so long because obstetricians continue to get better at determining which women would benefit more from cesarean rather than vaginal delivery, such that outcomes in both settings improve. We are not aware of any empirical evidence on the association between experience and clinical decision making skills among early career physicians, however.

Implications for policy and practice

Our findings that new obstetricians continue to improve for three decades have potentially important implications. Future efforts should be devoted to exploring these relations more deeply, with the aim of identifying features that could be exploited for quality improvement. These results suggest that delivery outcomes might be improved by shifting cases from less experienced to more experienced obstetricians. Although we saw a diminishing marginal effect of experience on outcomes, obstetricians with three decades of experience still have fewer maternal complications than their peers near the start of their careers. In contrast, obstetrician-gynecologists commonly reduce their obstetrical practice in later years, shifting more to gynecology, so that deliveries are preferentially performed by obstetricians with less experience. In our data, about 43% of deliveries were performed by physicians with no more than 10 years of experience, whereas only 2% were performed by those with 31-40 years of experience.

However, even if more seasoned physicians could be motivated to delay or reduce their shift to gynecology, the wisdom of doing so is questionable. Echoing concerns about regionalizing cardiovascular care in high volume hospitals,15 a shift of deliveries to more experienced obstetricians might limit the acquisition of experience for later cohorts of physicians, disrupting whatever processes underlie the experience-performance associations we found. A better approach might be to understand how experience promotes quality, with the hope of accelerating it, and to identify which aspects of delivery care vary between more and less experienced obstetricians. Further attention should be devoted to approaches that might help to advance physicians along the learning curve after residency training, such as coaching.16

Similarly, these results might be interpreted as guidance for patients to select their obstetrics providers on the basis of years of experience. Our results do show that average outcomes are better among more experienced physicians, at least for maternal complications. Years of experience may thus be one of potentially many factors patients should consider when selecting an obstetrician. At the same time, experience is only a proxy for quality of provider. Heterogeneity surely exists among physicians in the experience-performance relation, which we have not explored here, such that experience is no guarantor of quality. Accordingly, patients would be served better by having access to direct measures of physicians’ performance.

Strengths and limitations of study

This study has several limitations. Firstly, we relied on administrative data, which do not capture all differences in severity between patients or a complete range of patients’ outcomes. Our data include considerable clinical information reflecting observable comorbidities, however, and the possibility of unobserved comorbidity is low in the setting of obstetrics, where the vast majority of patients are healthy young women. Importantly, we could not observe child related delivery outcomes or assess the potential trade-off between maternal and neonatal outcomes. We also could not follow mothers across multiple deliveries or adjust for parity. Secondly, we studied years of experience, not cumulative volume. Experience and cumulative volume are highly correlated and thus difficult to separate. Although cumulative volume may be more conceptually appealing because it better captures the notion that “practice makes perfect,” better outcomes might drive more volume.1 17 This concern may be particularly justified in obstetrics, where patients have time to search for obstetricians. Because of this, and because years of experience is measured more reliably in our data and in actual practice settings, we focused on experience. Thirdly, owing to limited availability of data on physicians, we studied only obstetricians from Florida and New York, so the generalizability of our findings may be limited.

This study also has several strengths. In contrast to other studies of physicians’ learning curves,9 10 11 12 we used detailed data from two large states comprising more than 6 million deliveries performed by more than 5000 obstetricians over an 18 year period. Moreover, our findings persist across delivery mode, in models that take account of survivor bias, and regardless of adjustment for patients’ characteristics.

Conclusions

We found a large and persistent effect of physicians’ years of experience on maternal outcomes in obstetrics, which decreased as physicians progressed in their careers. If these effects are seen in other fields, they have potentially broad implications for the structure and improvement of medical education and continuing medical education and for projections of the effect of changing physician workforce demographics on healthcare delivery and quality.

What is already known on this topic

The notion that physicians’ performance improves with experience has intuitive appeal

Limited empirical evidence suggests that performance improves with experience only when physicians first perform a procedure, if at all, and that performance degrades as physicians near the end of their careers

What this study adds

Among obstetricians practicing in Florida and New York, greater number of years of experience was associated with a lower rate of maternal complications over the first 30 years of practice

Contributors: All authors were responsible for conception and design. AJE acquired the data, which all authors analyzed and interpreted. AJE drafted the manuscript, which all authors critically revised. AJE and JH were responsible for statistical analyses. AJE and DAA supervised the study. DAA provided administrative, technical, and material support. All authors had full access to the data, including statistical results and tables, for this study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. AJE is the guarantor.

Funding: This research was performed without external financial or material support. The authors maintained full control over the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study (protocol No 814219) was deemed HIPAA-compliant and exempted from review by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board, Philadelphia, PA.

Data sharing: The statistical code is available from the corresponding author at eandrew@mail.med.upenn.edu.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f1596

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

References

- 1.Huesch MD, Sakakibara M. Forgetting the learning curve for a moment: how much performance is unrelated to own experience? Health Econ 2009;18:855-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:260-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidak Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J Am Stat Assoc 1967;62:626-33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oehlert GW. A note on the delta method. Am Stat 1992;46:27-9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivas SS, Epstein AJ, Nicholson S, Herrin J, Asch DA. Improvement in US maternal obstetrical outcomes from 1992 to 2006. Med Care 2010;48:487-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA 2009;302:1277-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory KD, Korst LM, Gornbein JA, Platt LD. Using administrative data to identify indications for elective primary cesarean delivery. Health Serv Res 2002;37:1387-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopper AN, Jamison MH, Lewis WG. Learning curves in surgical practice. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:777-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridgewater B, Grayson AD, Au J, Hasan R, Dihmis WC, Munsch C, et al. Improving mortality of coronary surgery over first four years of independent practice: retrospective examination of prospectively collected data from 15 surgeons. BMJ 2004;329:421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vickers AJ, Bianco FJ, Serio AM, Eastham JA, Schrag D, Klein EA, et al. The surgical learning curve for prostate cancer control after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pisano GP, Bohmer RMJ, Edmondson AC. Organizational differences in rates of learning: evidence from the adoption of minimally invasive cardiac surgery. Management Science 2001;47:752-68. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huesch MD. Learning by ng, scale effects, or neither? Cardiac surgeons after residency. Health Serv Res 2009;44:1960-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waljee JF, Greenfield LJ, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD. Surgeon age and operative mortality in the United States. Ann Surg 2006;244:353-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waljee JF, Greenfield LJ. Aging and surgeon performance. Adv Surg 2007;41:189-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathore SS, Epstein AJ, Volpp KGM, Krumholz HM. Regionalization of acute coronary syndromes: more evidence is needed. JAMA 2005;293:1383-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawande A. Personal best. The New Yorker, October 3, 2011. (available at www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/10/03/111003fa_fact_gawande).

- 17.Epstein AJ. Effects of report cards on referral patterns to cardiac surgeons. J Health Econ 2010;29:718-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.