Abstract

BACKGROUND

The prevalence and characteristics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) were determined in this fourth study of first grade children in a South African community.

METHODS

Active case ascertainment methods were employed among 747 first grade pupils. The detailed characteristics of children within the continuum of FASD are contrasted with randomly-selected, normal controls on: 1. physical growth and dysmorphology; 2. cognitive/behavioral characteristics; and 3. maternal risk factors.

RESULTS

The rates of specific diagnoses within the FASD spectrum continue to be among the highest reported in any community in the world. The prevalence (per 1,000) is: FAS - 59.3 to 91.0; PFAS – 45.3 to 69.6; and ARND – 30.5 to 46.8. The overall rate of FASD is therefore 136.1 to 208.8 per 1,000 (or 13.6 to 20.9%). Clinical profiles of the physical and cognitive/behavioral traits of children with a specific FASD diagnosis and controls are provided for understanding the full spectrum of FASD in a community. The spectral effect is evident in the characteristics of the diagnostic groups and summarized by the total (mean) dysmorphology scores of the children: FAS = 18.9; PFAS = 14.3; ARND = 12.2; normal controls, alcohol exposed = 8.2; and unexposed = 7.1. Documented drinking during pregnancy is significantly correlated with verbal (r = -.253) and non-verbal ability (r = -.265), negative behaviors (r = .203) and total dysmorphology score (r = .431). Other measures of drinking during pregnancy are significantly associated with FASD, including binge drinking as low as three drinks per episode on two days of the week.

CONCLUSIONS

High rates of specific diagnoses within FASD were well documented in this new cohort of children. FASD persists in this community. The data reflect an increased ability to provide accurate and discriminating diagnoses throughout the continuum of FASD.

Keywords: fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, epidemiology, prevalence, diagnosis, South Africa, alcohol abuse, cognition, maternal drinking

Alcohol is a teratogen affecting birth outcomes for centuries (Sullivan, 1899; Armstrong, 2003). But the fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) diagnosis was not formalized until 1973 (Jones and Smith, 1973). Further delineation of the diagnosis of FAS continues (Bertrand, et al., 2005), especially of the specific characteristics of diagnoses within the continuum of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) (Aase, 1994; Astley and Clarren, 2000; Chudley et al., 2005; Hoyme et al., 2005; ICCFASD Consensus Statement on ARND, 2011; Sokol and Clarren, 1989; Stratton et al, 1996; Warren et al., 2004). This manuscript describes a population-based study of all IOM-based FASD diagnoses including alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND).

In three previous, active case ascertainment studies carried out in this South African (ZA) community, only FAS and partial fetal alcohol syndrome (PFAS) were the foci in this community where rates of FAS and FASD have been extremely high (May et al., 2000; 2007; Viljoen et al., 2005). First grade children have been studied as endorsed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and all three domains of diagnostic criteria have been fully addressed: child physical, behavioral, and maternal (Stratton et al., 1996). This is the fourth in-school study of this particular community (May et al., 2000, 2007; Viljoen et al., 2005) and fifth reported from ZA overall (Urban et al., 2008). Similar studies have been reported from Italy (May et al., 2006, 2011a), Croatia (Petković and Barišić, 2010), and a study and two pilots from the United States (Clarren et al., 2001; May et al., 2009). In-school studies have produced much higher rates of FASD than studies using other methodologies (May and Gossage, 2001; May et al., 2009), and they hold potential for clarifying the entire continuum of specific FASD diagnoses. The population of the Western Cape Province (WCP) of South Africa, (ZA) is 5.3 million people (Statistics South Africa, 2007); 50% are Cape Coloured (mixed race), 30% Black African, 18% White, and 2% other. Cape Town is the principal urban area of the WCP, and 40% of the population lives in small towns and rural areas. The study community is similar in socioeconomic character to others in the WCP; the 2011 population was 58,300 (28.1% rural).

Drinking among sub-segments of the Coloured population of the WCP has historically been documented to have a high rate of abusive drinking among men and women (Crome and Glass, 2000; London, 2000; Mager, 2004; Parry and Bennetts, 1998). Recreational binge drinking occurs regularly on weekends and holidays for many people (May et al., 2005; 2008b; Viljoen et al., 2002). Partially because of research initiated in 1997, high rates of FASD and alcohol abuse among females have become major concerns (Croxford and Viljoen, 1999; Khaole et al., 2004; Morojele et al., 2010). Baseline and ongoing assessment of FASD prevalence is needed for evaluating changes and prevention efficacy.

This paper describes a population-based sampling and diagnostic process, and the characteristics of FAS, PFAS, and ARND in a single population.

METHODS

The IOM diagnostic system (Stratton et al., 1996) has been used among first grade students in all ZA studies. Classification of children is based on a full consideration of: (1) physical growth and dysmorphology, (2) cognitive/behavioral assessments, and (3) maternal alcohol consumption, while ruling out other known genetic and teratogenic anomalies. Final diagnoses are made for each child in a formal, data- driven case conference per the clarified guidelines and operational criteria suggested by the IOM (Hoyme et al., 2005).

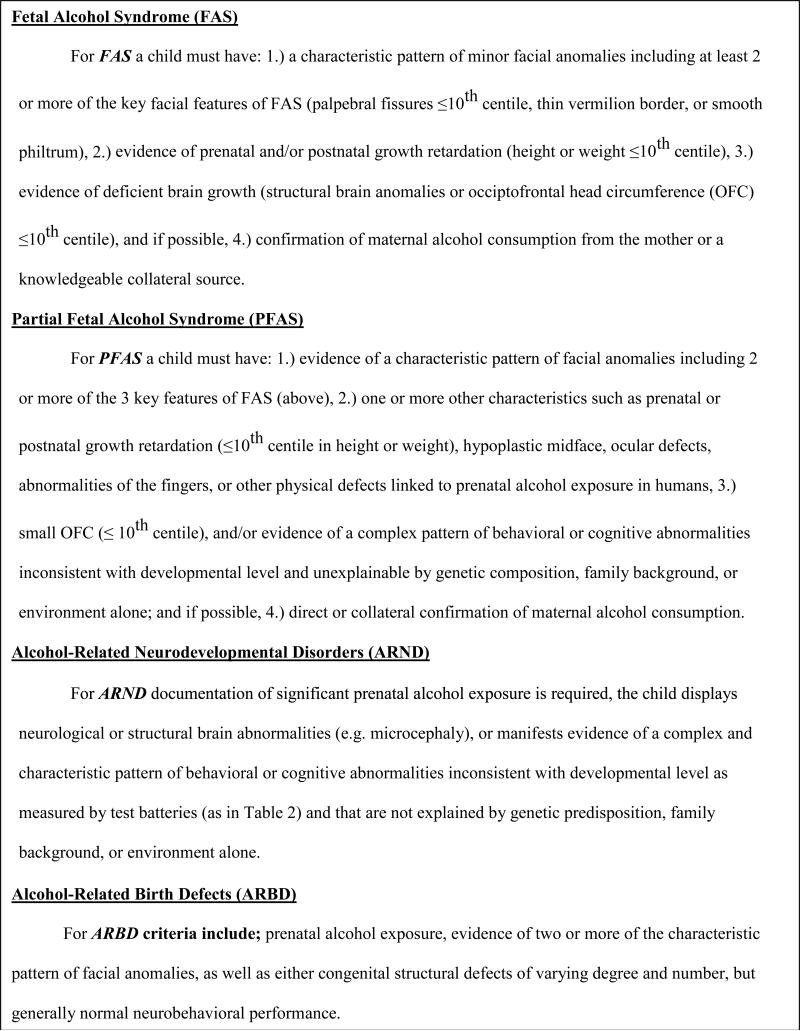

The IOM continuum of FASD contains four diagnoses: FAS, PFAS, ARND, and alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD) (Stratton et al., 1996). Each of the IOM diagnoses as presented in Figure 1 was utilized in this study. We have found ARBD to be rare in any population; and no cases were diagnosed in this study. While the diagnosis of FAS or PFAS without a confirmed history of alcohol exposure is viewed as tentative, original IOM criteria allow for an FAS diagnosis without direct (maternal) reports of use (Stratton et al., 1996): similarly, revised criteria (Hoyme et al., 2005) permit a diagnosis of PFAS if other evidence of drinking exists (e.g. collateral reports). Many women underreport drinking during pregnancy (Alvik et al., 2006; Wurst et al., 2008), but in this study ZA population, the diagnosis is rarely made without direct maternal reporting of alcohol use.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the Diagnoses within the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) as Defined by the Institute of Medicine and Revised Criteria by Hoyme et al., 2005.

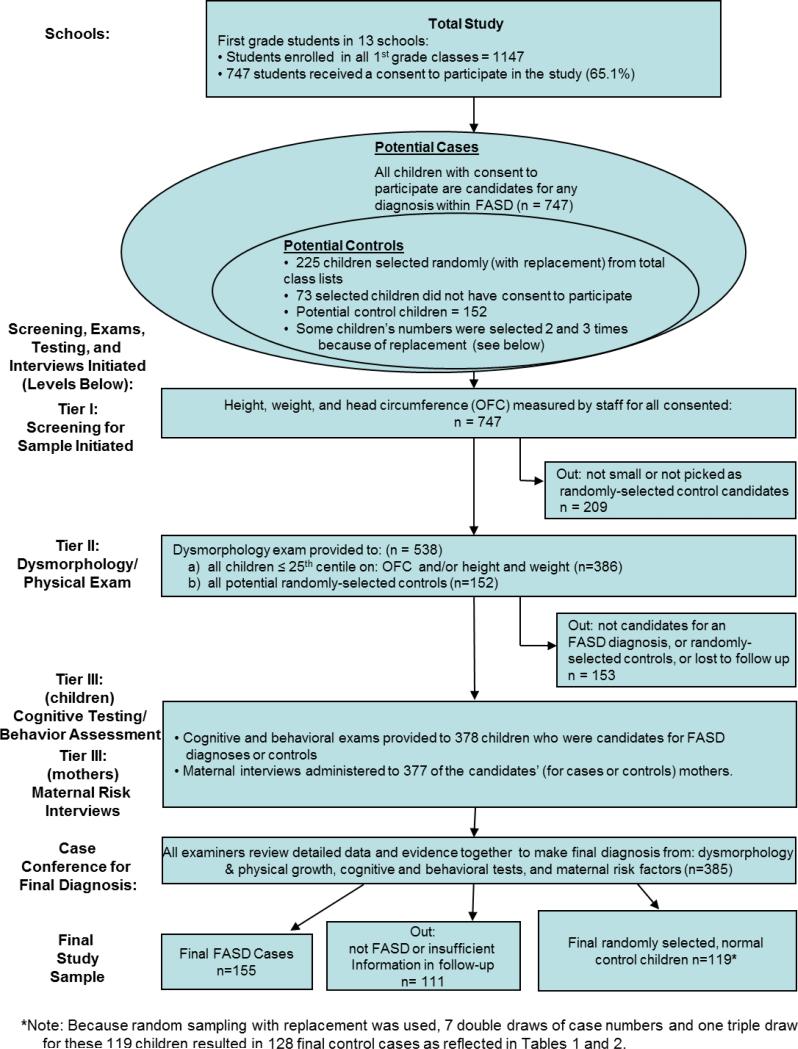

Sampling of First Grade Children with FASD and Controls

Three-tier screening methods were used to identify FASD cases (See Figure 2). Oversampling for growth deficiency and small head circumference and random selection of controls was undertaken among all students in the first grade of the primary schools of the community. There were 1147 1st grade children enrolled in 13 primary schools, and 747 (65.1%) children had active consent to participate. The control children provide a representative, community-specific comparison group; 225 enrolled student's numbers were randomly-selected (with replacement). The final control sample represents 119 children, 7 of whom had their number chosen twice and one whose number was drawn three times. Therefore the final number of control cases in the Tables is 128 (See Figure 2). Sampling with replacement: selects values that are truly independent of each other, have zero covariance with each other, and is particularly useful when the theoretical distribution of a condition is unknown (Adèr et al., 2008). Identical exams and testing were performed on subjects and controls.

FIGURE 2.

Methodology of the South African IV FASD study with Sampling Procedures and Numbers

Screening and testing in Three Tiers I through III

In Tier I, all consented children were measured on: height, weight, and head circumference (OFC). Any consented child ≤ 25th centile on head circumference (OFC) and/or both height and weight, and all children whose numbers had been randomly selected from class rolls as candidates for controls were referred to Tier II (physical exam); 538 children met these criteria (Figure 2). Surveillance of local institutions for developmental disabilities yielded no additional age-appropriate cases of suspected FASD.

In Tier II, four dysmorphology exam teams provided exams covering: facial and body dysmorphology, growth, and heart function. Each team had a pediatric dysmorphologist; a scribe to record data; program staff to oversee clinic flow and two dimensional photos. All examiners were blinded from prior knowledge of children and mothers. Inter-rater reliability for quantitative measurements was found to be good in previous ZA samples (May et al., 2000; Viljoen et al., 2005), and more recently in American schools where Cronbach's alpha coefficients were: 0.993 for OFC, 0.957 for inner canthal distance (ICD), 0.951 for palpebral fissure length, and 0.928 for philtrum length. For the more subjective elements of the diagnosis of an FASD, reliability measures for this sample were: lipometer ratings (Astley and Clarren, 2000) produced a Cronbach's alpha of .761for the philtrum and .648 for the vermillion.

After the Tier II dysmorphology exams, a preliminary diagnosis was assigned: a.) not-FAS, b.) diagnosis deferred – possible FASD, or c.) probable FAS. Therefore, children with the appearance, growth, or some minor anomalies characteristic of an FASD (b. and c. above), and also the randomly-selected, potential controls, were advanced to Tier III.

Tier III - Cognitive and Behavioral Testing and Maternal Risk Factor Questionnaires

Development and behavior were assessed in Tier III with: Tests of the Reception of Grammar (TROG), a measure of verbal IQ (Bishop, 1989); Colored Progressive Matrices (Raven, 1981) for non-verbal IQ; the WISC-IV Digit-Span Scaled Score (Wechsler, 2003) for executive functioning; and the Teacher Report Form for problem behaviors (Achenbach and Rescorla, 2001).

The mothers of randomly-selected controls were the maternal controls. All maternal risk interviews were administered in the field by experienced, Afrikaans-speaking staff. Multiple items were carefully sequenced to enhance sensitivity and maximize accurate reporting. They covered: general health, reproduction, nutrition, alcohol use, socio-economic status (SES), and physical measurements. Drinking questions followed a timeline, follow-back sequence (Sobel et al., 1988; 2001), and used vessels methodology pictures tailored to the common, local community alcohol products and drinking practices (Kaskutas and Graves, 2000; 2001; Kaskutas and Kerr, 2008). A seven-day, retrospective drinking log of alcohol consumption during the week preceding the interview was embedded into the nutrition questions. Current drinking data establish a baseline understanding of alcohol use and aid accurate calibration of drinking quantity, frequency, and timing (during pregnancy) for subsequent questions regarding alcohol use: 3 months prior to the index pregnancy, during the pregnancy(for each trimester by weekend, by weekdays, and by month) (May et al., 2000, 2005; 2007; 2008a,b; Viljoen et al., 2002). This sequencing minimizes under-reporting (Alvik et al., 2006). Retrospective reports of alcohol use during pregnancy are considered more accurate for determining prenatal drinking levels than those reported during the prenatal period (Czarnecki et al., 1990; Hannigan et al., 2010). These methods, sequencing, and contextual frameworks work well, especially when embedded within a dietary inventory (King, 1994).

Information on maternal risk factors for the index pregnancies was gathered for 377 women. All but 13 mothers of cases and controls were interviewed: 5 (1.3%) had moved, and 8 (2.1%) refused. Some data regarding alcohol consumption during the index pregnancy (17.2% of cases) were obtained via collaterals (usually relatives). Maternal data presented here focus primarily on confirmation of maternal drinking for case diagnosis in the epidemiological study while other maternal risk factors for this community have been reported elsewhere (May et al., 2005; 2008a,b). Alcohol use during the index pregnancy was confirmed directly or through collateral sources in 100% of the ARND cases. Nine of the 68 (13.2%) FAS cases, and 6 of the 52 PFAS (17.1%) cases were diagnosed without confirmation of prenatal drinking.

Tobacco use data current and prenatal were also obtained in the interviews. In earlier community trials we determined that each cigarette averaged one gram of tobacco (May et al., 2000; Viljoen et al., 2002), similar to machine-rolled cigarettes in the U.S.A. (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Tobacco/cigars).

Final Diagnoses Made in Multi-Disciplinary Case Conferences

After completing collection of all data, final diagnoses for each child were made in structured, case conferences at the program offices at Stellenbosch University. The researchers who had performed the exams, testing, and the maternal interviews all participated and provided their data and assessments for each child. During the case conference 2-D pictures of each child were projected on a screen for viewing. After a detailed review of data for each child on the 3 domains of information and discussion of how the totality of the findings met the criteria for an FASD diagnosis, another anomaly, or not FASD, final diagnoses were made by the dysmorphologists.

Data Analysis

Data were entered via EPI Info (Dean et al., 1994), and analyses performed with SPSS, version 19 (SPSS, 2010). Categorical variables comparing cases to controls were analyzed by chi-square, continuous variables by one way analysis of variance, and bi-variate, post-hoc comparisons with Dunnett's C, is a post hoc analysis that controls for the alpha error (Type 1; false positive) produced when performing multiple comparisons of group means (Tabachnick and Fidel, 2007). In Table 4, Pearson correlation coefficients compare selected variables, two of which were utilized as dummy variables (three or more drinks per occasion or 5 or more drinks per occasion), with alpha levels set at .05 (two-tailed). In Table 5 the estimated prevalence rates for the diagnoses within the FASD continuum is calculated as a range of low to high based on two denominators: 1.) all students in the first grade (enrollment rate), and 2.) all consented children (sample rate). Because of oversampling of smaller children in Tier II (physical exam) of the study (≤ 25th centile on height and weight and/or OFC), the high rate may be too high, and the lower rate is likely more realistic, with the actual prevalence within the range (May et al., 2011a,b).

TABLE 4.

Pearson Correlation Coefficient for Developmental1 and Physical Dysmorphology vs. Selected Maternal Drinking Measures During Pregnancy: South Africa Wave IV

| Trait | Reported Drinking During Pregnancy (N = 339) | Drinks Per Month (n = 302) | Drinks Per Day (n = 302) | 3 Drinks Per Occasion (n = 302) | 5 Drinks Per Occasion (n =302) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal abilitya | -.253*** | -.170** | -.174** | -.190** | -.158** |

| Non-verbal abilityb | -.265*** | -.194** | -.209*** | -.218*** | -.210*** |

| Behaviorc | .203*** | .172** | .232*** | .237*** | .233*** |

| Dysmorphology score | .431*** | .353*** | .378*** | .467*** | .384*** |

All scores standardized for age of child at time of testing.

Tests of the Reception of Grammar (TROG).

Raven Colored Progressive Matrices.

Personal Behavior Checklist (PBCL-36).

*p <.05

p <.01

p <.001

TABLE 5.

Prevalence Rates (per 1,000) of Individual Diagnoses within the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Total FASD: South African Community, Wave IV

| Diagnosis | n | % Rural* | Enrolled rate1 (n=1147) | Consented rate2 (n=747) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAS | 68 | 49.1 | 59.3 | 91 |

| PFAS | 52 | 47.6 | 45.3 | 69.6 |

| ARND | 35 | 46.7 | 30.5 | 46.8 |

| Total FASD | 155 | 48.1 | 135.1 | 207.5 |

| FAS and PFAS only | 120 | 48.5 | 104.6 | 160.6 |

Percentage of the cases in each diagnostic category from rural areas. The total population of this area living in rural areas is 28%.

Denominator is all children attending first grade in local schools.

Denominator is the total number of child with consent to participate in this study.

RESULTS

In Table 1, column 1, data are presented for all consented children who were measured only for height, weight, and head circumference. The mean age was 6.8 years (81.4 months), children averaged 115.8 cm in height, weighed 20.7 kg, and had OFC of 50.9 cm. Comparing the combined control groups with the total consented column, there are minimal differences. In the other columns, 68 of the children were diagnosed with FAS, 52 with PFAS, and 35 with ARND. Thirty-one of the children who were initially chosen randomly for the control group (20.4%) were eventually diagnosed within the FASD spectrum (7 with FAS, 12 with PFAS and 12 with ARND). These children were removed from the potential control group and assigned to their respective FASD group (Table 1).

Table 1.

South Africa Wave IV Children's Demographic and Growth Parameters & Post Hoc Analyses

| Variable | All Children1 (n=747) | Children with FAS (n = 68) | Children with Partial FAS (n = 52) | Children with ARND (n =35 ) | Exposed R-S Controls (n = 38) | Unexposed R-S Controls (n = 90) | Statistical Test | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | ||||||||

| Males | 49 | 50 | 48.1 | 51.4 | 50 | 54.4 | χ2 = 0.64 | 0.958 |

| Females | 51 | 50 | 51.9 | 48.6 | 50 | 45.6 | ||

| Age (months) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 81.4 (7.1) | 85.4 (8.7) | 81.4 (9.5) | 84.0 (7.9) | 80.7 (6.7) | 80.0(6.2) | F = 5.57 | 0.000 |

| Height (cm) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 115.8 (5.9) | 111.9 (5.5) | 114.8 (7.5) | 113.5 (4.9) | 115.6 (5.5) | 116.3 (6.3) | F = 5.50 | 0.000 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.7 (3.6) | 17.7 (2.1) | 20.0 (3.1) | 18.9 (1.9) | 20.5 (2.7) | 21.1 (3.5) | F = 15.83 | 0.000 |

| Average BMI for Age | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (9.0) | 15.5 (0.2) | 15.4 (0.2) | 15.5 (0.2) | 15.4 (0.2) | 16.9 (14.8) | F = 0.49 | 0.743 |

| Child's BMI | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.3 (1.6) | 14.2 (1.1) | 15.0 (1.0) | 14.6 (1.2) | 15.3 (1.1) | 15.4 (1.8) | F = 9.24 | 0.000 |

| BMI Percentile | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.9 (27.5) | 16.5 (16.9) | 37.0 (21.2) | 27.8 (25.3) | 43.6 (25.0) | 47.4 (24.9) | F = 20.49 | 0.000 |

| Occipital Circumference (OFC; in cm) Mean (SD) | 50.9 (2.4) | 48.6 (1.3) | 50.0 (1.3) | 49.4 (0.8) | 51.1 (1.2) | 51.1 (1.5) | F = 42.69 | 0.000 |

| Palpebral Fissure Length (cm) Mean (SD) | -- | 2.31 (0.2) | 2.35 (0.1) | 2.39 (0.1) | 2.43 (0.1) | 2.45 (0.1) | F = 17.80 | 0.000 |

| Inner Canthal Distance (cm) | -- | 2.80 (0.2) | 2.88(0.4) | 2.73 (0.2) | 2.81 (0.3) | 2.91 (0.5) | F = 2.04 | 0.090 |

| Percent Palpebral Fissure Length (%) is of Inner Canthal Distance | -- | 83.1 (9.7) | 82.7 (10.2) | 87.8 (7.9) | 87.4 (9.6) | 85.7 (9.7) | F = 2.87 | 0.024 |

| Inner Pupilary Distance (cm) | -- | 5.0 (0.2) | 5.0 (0.4) | 5.0 (0.2) | 5.1 (0.7) | 5.1 (0.5) | F = 1.30 | 0.270 |

| Philtrum Length (cm) Mean (SD) | -- | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | F = 1.81 | 0.126 |

| Maxillary Arc (cm) | -- | 23.2 (0.8) | 23.8 (1.0) | 23.5 (1.1) | 24.1 (0.9) | 23.8 (2.6) | F = 2.59 | 0.037 |

| Mandibular Arc (cm) | -- | 23.9 (0.9) | 24.7 (1.2) | 24.4 (1.1) | 25.1 (1.1) | 25.1 (0.9) | F = 15.28 | 0.000 |

| Short Inner Canthal Distance (%) | -- | 32.8 | 21.2 | 38.2 | 23.7 | 20 | χ2 = 6.70 | 0.153 |

| Short Inner Pupilary Distance (%) | -- | 60.6 | 36.5 | 51.4 | 28.9 | 12.2 | χ2 = 44.22 | 0.000 |

| Hypoplastic Midface (%) | -- | 82.4 | 71.72 | 62.9 | 50 | 42.2 | χ2 = 30.54 | 0.000 |

| Smooth Philtrum2 (%) | -- | 80.9 | 80.8 | 22.9 | 31.6 | 22.5 | χ2 = 87.93 | 0.000 |

| Narrow Vermillion Border3 (%) | -- | 89.7 | 94.2 | 25.7 | 42.1 | 28.1 | χ2 = 106.69 | 0.000 |

| “Railroad Track” Ears (%) | -- | 10.3 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 10.5 | 5.6 | χ2 = 2.16 | 0.706 |

| Strabismus (%) | -- | 5.9 | 1.9 | 0 | 7.9 | 4.4 | χ2 = 3.95 | 0.413 |

| Ptosis (%) | -- | 14.7 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 | 5.6 | χ2 = 12.40 | 0.015 |

| Epicanthal Folds (%) | -- | 63.2 | 63.5 | 80 | 52.6 | 39.3 | χ2 = 21.04 | 0.000 |

| Flat Nasal Bridge (%) | -- | 60.3 | 55.8 | 57.1 | 42.1 | 37.1 | χ2 = 11.13 | 0.025 |

| Anteverted Nostrils (%) | -- | 50 | 38.5 | 31.4 | 34.2 | 36 | χ2 = 5.02 | 0.285 |

| Prognathism (%) | -- | 7.4 | 5.8 | 2.9 | 0 | 2.2 | χ2 = 4.94 | 0.294 |

| Heart Murmur (%) | -- | 17.6 | 13.5 | 8.6 | 10.5 | 6.7 | χ2 = 5.18 | 0.296 |

| Heart Malformations (%) | -- | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | χ2 = 6.50 | 0.165 |

| Hypoplastic Nails (%) | -- | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 2.6 | 2.2 | χ2 = 2.04 | 0.728 |

| Limited Elbow Supination (%) | -- | 1.5 | 1.9 | 0 | 5.3 | 1.1 | χ2 = 3.56 | 0.471 |

| Clinodactyly (%) | -- | 60.3 | 63.5 | 48.6 | 57.9 | 65.2 | χ2 = 3.20 | 0.525 |

| Camptodactyly (%) | -- | 27.9 | 23.1 | 11.4 | 10.5 | 6.7 | χ2 = 16.25 | 0.003 |

| Palmar Crease Alteration (%) | -- | 48.5 | 28.8 | 37.1 | 39.5 | 21.3 | χ2 = 14.07 | 0.007 |

| Hirsute (%) | -- | 0 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | χ2 = 8.95 | 0.062 |

| Total Dysmorphology Score Mean (SD) | -- | 18.9 (3.9) | 14.3 (3.1) | 12.2 (3.3) | 8.2 (3.6) | 7.1(3.6) | F = 123.43 | 0.000 |

| Dunnett's C Post-Hoc Analyses | |

|---|---|

| Measure | Groups that differ at the P = .05 level |

| Age (months) | • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls |

| Height (cm) | • FAS & Unexposed Controls • FAS & Exposed Controls |

| Weight (kg) | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & ARND • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Exposed Controls |

| Child's BMI | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls |

| BMI Percentile | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls • FAS & PFAS |

| Occipital Circumference (OFC; in cm) | • FAS & ARND • FAS & Unexposed Controls • FAS & Exposed Controls • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & Exposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Exposed Controls |

| Palpebral Fissure Length (is of Inner Canthal Distance; cm) | • FAS & ARND • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & Exposed Controls • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

| Maxillary Arc (cm) | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & PFAS |

| Mandibular Arc (cm) | • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Exposed Controls |

| Total Dysmorphology Score | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & ARND • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & ARND • PFAS & Exposed Controls • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Exposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

The “All Children” group is not included in any of the Table 1 analyses.

Scores of 4 or 5 on Astley Lip Philtrum Guide.

Scores of 4 or 5 on Astley Lip Philtrum Guide.

4 Dunnett's C post hoc analyses show the following groups differ at the P = .05 level: FAS & Exposed Controls, FAS & Unexposed Controls, PFAS & Unexposed Controls, ARND & Unexposed Controls, Exposed & Unexposed Controls.

Average age varies significantly across diagnostic groups, as the FAS and ARND children are older due to repeating 1st grade. Overall, the means of 20 variables in Table 1 are statistically significantly different between the 5 groups: age, height, weight, BMI, BMI percentile, head circumference, palprebral fissure length (PFL), percentage the PFL is of the inner canthal distance, maxillary arc, mandibular arc, short innerpupilary distance, hypoplastic midface, smooth philtrum, narrow vermilion border, ptosis, epicanthal folds, flat nasal bridge, camptodactly, altered palmar creases, and total dysmorphology score. Also, innercanthal distance and hirsutism approached significance. Many of the traits exhibit a spectrum across the five study categories, with PFAS means having the most frequent divergence from of the spectral pattern. The high standard deviations for the PFAS group on many traits indicate a higher degree of variability for many of the features than the variability within other diagnostic groups. Most of the non-significant variables are clinical observational variables and are proximal to the FASD diagnosis. Total dysmorphology scores, which represent a summary value and where higher values indicate more features of FASD, form a perfect spectrum for the diagnostic groups (18.9 for FAS, 14.3 for PFAS, 12.2 for ARND), and for the controls based on alcohol exposure, 8.2 and for the exposed and 7.1 for unexposed controls (F = 123.43, p < .001).

Also in Table 1, Dunnett's C post-hoc bi-variate between groups analyses indicate that weight, OFC, palbebral fissure length, and total dysmorphology score are the most significant differentiators between each and every one of the specific FASD diagnostic groups including exposed and unexposed controls. ARND was differentiated from the alcohol-exposed control group by three of the above four variables and also by mandibular arc measures.

Developmental Indicators

Table 2 presents cognitive/behavioral test results. Children with PFAS are inconsistent with a linear spectral pattern within the three FASD categories, but their performance is inferior to either of the control groups. The exposed controls performed worse on all measures than unexposed controls. PFAS children are again demonstrating less homogeneity as indicated by larger standard deviations for most measures. Verbal and non-verbal ability and Digit Span performance were significantly lower for FAS and ARND groups than for PFAS; but all FASD groups performed poorly when compared to controls. ARND children had the most reported behavioral problems (the Achenbach scores) followed by FAS, PFAS, and alcohol-exposed controls. The post-hoc analyses in Table 2 indicate that non-verbal IQ and the Digit Span are discriminating cognitive/behavioral measures between FASD groups and controls, particularly the unexposed controls. Only non-verbal ability discriminates between the FAS and PFAS group and PFAS and ARND groups. None of the cognitive/behavioral tests are effective at discriminating between exposed and unexposed controls. Dysmorphology discriminates more consistently than these tests alone.

TABLE 2.

South Africa Wave IV Mean Scores on Developmental and Behavioral Indicators1 of Children with FAS, PFAS, and ARND Compared to Controls & Post Hoc Analyses

| Child Variables | FAS (SD) (n =66) | PFAS (SD) (n = 51) | Children with ARND (SD) (n = 35) | Exposed R-S Controls (SD) (n = 38) | Unexposed R-S Controls (SD) (n= 87) | Test Score | d.f. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Developmental Traits

| ||||||||

| Verbal IQa | 5.1 (7.6) | 5.7 (10.2) | 5.2 (7.5) | 8.2 (7.9) | 13.4 (18.2) | F = 5.85 | df = 4/272 | 0.000 |

| Non-verbal IQb | 8.9 (7.2) | 14.4 (12.1) | 7.7 (4.5) | 17.8 (10.9) | 22.2 (18.1) | F = 14.23 | df = 4/272 | 0.000 |

| WISC-IV Digit-Span Scaled Score | 4.4 (2.6) | 5.1 (2.8) | 4.7 (2.7) | 6.8 (3.5) | 6.7 (3.3) | F = 8.07 | df = 4/271 | 0.000 |

| Achenbach Teacher Report Form | 50.2 (42.6) | 45.1 (42.2) | 58.3 (33.7) | 35.8 (35.5) | 29.1 (29.1) | F = 5.63 | df = 4/272 | 0.000 |

| Dunnett's C Post-Hoc Analyses | |

|---|---|

| Measure | Groups that differ at the P = .05 level |

| Verbal IQ | • FAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

| Non-verbal IQ | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & ARND • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Exposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

| WISC-IV Digit-Span Scaled Score | • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

| Achenbach Teacher Report Form | • FAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

| Total Dysmorphology Score | • FAS & PFAS • FAS & ARND • FAS & Exposed Controls • FAS & Unexposed Controls • PFAS & ARND • PFAS & Exposed Controls • PFAS & Unexposed Controls • ARND &Exposed Controls • ARND & Unexposed Controls |

All scores standardized for age of child at time of testing.

Tests of the Reception of Grammar (TROG). A measure of verbal intelligence

Raven Colored Progressive Matrices. A measure of non-verbal intelligence.

Maternal Drinking and Smoking

In Table 3 91%, 89.1%, and 96.8% of the mothers of FAS, PFAS, and ARND children reported drinking during pregnancy, compared to 29.7% (38/128) of the mothers of normal controls. The remaining data in Table 3 further support, with only a few exceptions, the causal role that alcohol consumption plays in FASD. Mean number of drinks per week and drinking three and five or more drinks per occasion during pregnancy both illustrate the significant difference between mothers of FASD children and those of normal children. Mothers of FAS, PFAS and ARND children report drinking an average of 13 drinks per week, with large standard deviations indicating many drinkers are well above the average. Control mothers who drink consumed 5.6 drinks each week and are less likely to binge with five or more drinks. In the post hoc analyses for Table 3, average number of drinks per week differentiates the various groups the best.

TABLE 3.

Substance Use By Mothers and Fathers of the Children with FASD and Controls: South Africa Wave IV

| Maternal Variables | Mothers of Children with FAS (n = 68) | Mothers of Children with Partial FAS (n = 52) | Mothers of Children with ARND (n = 35) | Mothers of R-S Exposed Control Children (n =38) | Mothers of R-S Unexposed Control Children (n = 90) | Statistical Test | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking Indicators overall reported drinking during pregnancy (%) | 91.4 | 89.1 | 96.8 | 100 | -- | χ2 = 201.97 | df = 4 | 0.000 |

| Average No. drinks per week (during pregnancy) | 13.4 (14.0) | 13.1 (16.1) | 13.0 (15.0) | 5.6 (5.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | F = 16.43 | df = 4/207 | 0.000 |

| Consumed 3 drinks or more per occasion during pregnancy (%) | 78.8 | 74.4 | 80.8 | 70.6 | 0 | χ2 =117.22 | df = 4 | 0.000 |

| Consumed 5 drinks or more per occasion during pregnancy (%) | 59.6 | 53.8 | 61.5 | 41.2 | 0 | χ2 =69.92 | df = 4 | 0.000 |

| Current drinker in last year (%) | 100 | 96.9 | 100 | 92.3 | 46 | χ2 = 57.70 | df = 4 | 0.000 |

| Drinking before index pregnancy (%) | 81.6 | 94.6 | 100 | 93.3 | 10 | χ2 = 101.28 | df = 4 | 0.000 |

| Drank during trimesters (%) | ||||||||

| 1st | 84.6 | 82.5 | 100 | 88.2 | - | χ2 = 155.09 | 0.000 | |

| 2nd | 73.1 | 70 | 84.6 | 47.1 | - | χ2 = 106.97 | 0.000 | |

| 3rd | 62.7 | 52 | 52 | 41.2 | - | χ2 = 69.65 | 0.000 | |

| Tobacco Use | ||||||||

| Smoked during index pregnancy (%) | 86 | 94.3 | 86.4 | 52.9 | 35.2 | χ2 = 51.33 | 0.000 | |

| Current smoker, whole sample (%) | 97.7 | 78.1 | 100 | 90.9 | 92.9 | χ2 = 1191 | 0.018 | |

| Quantity of tobacco used per week (Mean g) (SD) | ||||||||

| Whole sample: quantity of cigarettes smoked per week (each cigarette = 1 gram)1 | 33.0 (18.6) | 61.9 (54.9) | 48.2 (35.2) | 40.2 (21.1) | 54.5 (32.6) | F = 3.16 | 0.017 | |

| Father's data | ||||||||

| Fathers of Index Children with drinking problems in the past (%) | 61.9 | 39.1 | 50 | 54.5 | 38.7 | χ2 = 5.13 | 0.274 | |

Dunnett's C post hoc analyses show that FAS and Unexposed Controls differ at the P = .05 level.

Also in Table 3, mothers of the three FASD groups drank throughout all trimesters with less than half quitting in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters; the drinking mothers of the controls reported an even greater reduction in percentage drinking. More mothers of FASD children used tobacco at interview and during the index pregnancy, although the percentage smoking was high across groups. Smokers in this ZA population reported smoking 33 to 62 hand-rolled cigarettes per week which is modest compared to female smokers in the U.S.A. who report an average of 105 per week (CDC, 2005). Fathers are reported by the interviewees to have drinking problems. While 61.9% of FAS case fathers have had drinking problems, 38.7% of the unexposed control fathers have also had problems.

In Table 4, correlations indicate that verbal and non-verbal ability are significantly, negatively correlated with mother's reported drinking during pregnancy (r = -.253 and -.265), and reported episodes of three (r = -.190 and -.218) or five alcoholic drinks per day (r = - .158 and -.210). Behavioral problems are also significantly correlated with the same drinking measures, the more drinking the greater the problem behaviors Also, the more maternal drinking reported per month and per day, the lower the child's I.Q. and more behavior problems. The highest correlations in Table 4 are between dysmorphology scores and drinking measures, especially binge episodes of 3 drinks or more (r = .467).

Urban/Rural Distribution and Prevalence of FAS

In Table 5, mothers of FASD children were disproportionately more likely than controls to have resided in rural areas during gestation. While only 28% of the population lives in rural areas, between 46 and 49% of the FASD cases come from the rural areas.

The prevalence of FAS among the sample of children examined was 59.3 per 1,000 children enrolled in first grade classes, or 91.0 if the sample of consented children is used as the denominator (See Table 5). The total FASD rate is between 135.1 and 207.5 per 1,000, an unprecedented high prevalence of FASD reported for any population.

Another estimated prevalence rate can be obtained from the proportion of children from the random selection list of potential controls who converted to an FASD. Thirty-one of 152 children received an FASD diagnosis, a prevalence of 203.9 per 1,000, within the range produced by the oversampling method above.

DISCUSSION

By screening children into the study with an oversampling of children ≤ 25th centile on three measures (rather than a ≤ 10th centile as in past studies), far more (of the larger) children received physical exams and testing. Therefore, more ARND cases were diagnosed. These sampling criteria and the continued use of randomly selected controls has provided an opportunity to define and diagnose more of the spectrum of specific FASD diagnoses. While the prevalence rates from this study may appear to be a substantial increase in rates for this community over previous studies, the rates of FAS and FAS/PFAS combined in this community appear to have remained relatively stable over the years. Because about half of the women in this community drink alcohol, primarily as a weekend recreational activity, and one-quarter continue through the duration of pregnancy, it is a high FASD prevalence population. Much of the knowledge of the characteristics of FASD from this community can be extrapolated to other populations for we have consistently found that less than 2% of all women report any use of other drugs, making prenatal exposures to teratogens virtually alcohol exclusive.

Limitations

While this is the most comprehensive population-based study of FASD in a community to date, there are limitations. First, the number providing active consent in this community has degraded slightly over time. Parents providing permission for their children to participate was lower this time: 98.2%, 93.6%, and 80.7% in waves 1, 2, and 3, and 65.1% in this wave. A shorter turn-around time given to parents for consent and a single distribution of the consent forms in this sample produced this effect. Active consent is still higher than in many other populations and studies. For example, in an in-school study in Washington State with active consent, only “about 25%” consent was obtained (Clarren et al., 2001). In Italy consent rates averaged 49% in two in-school samples (May et al., 2006; 2011a,b); yet, high rates of FASD were found indicating an ability to capture representative cases using oversampling methods for undersized children. And in a recent in-school study in Croatia, 50% of the children were consented, and rates of FASD were found to be as high as the Italian samples (Petkovic and Barisic, 2010). By oversampling children who are small for height, weight, and head circumference, we are likely assessing a substantial proportion of the children with an FASD which can then be projected to the entire enrolled population. Furthermore, by calculating rates of the various FASD diagnoses with both consented sample and all enrolled student denominators, a range of estimated (high and low) prevalence is provided. The rate of conversion of randomly-selected controls to an FASD diagnosis provides a check. If this rate falls within the upper and lower estimate, then there is some assurance of the accuracy of the range. Some studies of FASD prevalence have ignored the dilemma of non-consented children and only a single, sample rate is provided. Second, another weakness might be that the FASD rates and traits of FASD found in ZA may have limited comparability to other populations. This particular region in ZA remains unique in culture and character from most others in the world, and it is this unique situation that has led to a “worst case scenario” for the prevalence and severity of FASD. While FASD rates are far higher than in other populations, study in this community is valuable for advancing basic knowledge about FASD. Examples of this include: the opportunity to apply and accurately define specific diagnostic criteria for all forms of FASD; an understanding of the continuum of patterns of fetal damage; and the opportunity to link FASD to specific maternal traits (co-factors of causation) with large numbers of FASD cases that are applicable to all human populations. Because maternal conditions are measurably more challenging in this ZA population, observations are more easily made for enhanced insight, and, variable degrees of these same conditions can be examined in other populations. For example, the fact that mothers of FASD children were significantly lower in body mass index (BMI) in the ZA studies (May et al., 2004; 2005; 2008a,b) provides an important link between adequate maternal nutrition and prenatal alcohol use which can be examined elsewhere. Poor nutrition in this population and others may radically increase the severity of damage to the offspring and limit the growth and development of these children overall. Third, another possible weakness is that we have not diagnosed any cases of ARBD in this large sample. But, we have repeatedly found that children with an ARBD are very rare in any population, for prenatal alcohol exposure in the prenatal period rarely damages physical features without also affecting cognitive and behavioral traits. Fourth, this study detected more cases of FAS and PFAS than reported from more developed populations such as Europe or the United States. The preponderance of severe dysmorphology, and therefore FAS and PFAS, is likely due to two factors: 1.) the surveillance system and first diagnostic exam are based on growth and dysmorpholgy, and 2.) there is severe growth restriction in this population. If a cognitive/behavioral screen were instituted first, then more cases of ARND would likely be diagnosed. And if growth restriction were not so common, then more of the cases classified as FAS might be diagnosed instead as PFAS or ARND. This may have been the reason that in similar studies in Italy there was a ratio of 4.5 cases of PFAS to every case of FAS (May et al., 2011a,b), very different than in this study. Overall growth in the Italian first grade population was better than that of this community.

Contributions

This study reports on the full spectrum of FASD diagnoses within a population. Specific traits of the three most common diagnoses within the spectrum are provided in detail. The children are well placed into their respective categories of FASD and significantly differentiated by statistical tests of the means of many physical and behavioral variables, especially total dysmorpholgy score. The general, average traits of FAS, PFAS, ARND and exposed control children are especially recognizable when studying multiple cases at one time in a population. Variance around the mean values is also evident, and progress is being made at differentiating the specific modal traits and characteristics that separate FAS, PFAS, and ARND from controls (both exposed and unexposed) and from one another.

In this cohort PFAS has proven to be most variable in its defining traits. The FAS and ARND categories seem to be more homogeneous. More analysis of the various alcohol exposure and maternal risk variables is needed, but in this first analysis it seems that the mothers of PFAS children drink episodically at similarly high levels as the mothers of FAS children; but the binge drinking vary more in their frequency causing a less consistent pattern of traits. The post-hoc analysis of bi-variate group comparisons indicate that the most significant physical differentiators between each FASD diagnostic group and exposed and unexposed controls are: child weight, OFC, palbebral fissure length, and total dysmorphology score. Of the cognitive/behavioral tests employed, non-verbal scores discriminate most between diagnostic groups.

The epidemiological research methods described here continue to improve, and have been used with over 3,500 children in this community alone. With progress made in the in-school studies and case conferences valid distinctions between levels of dysmorphia and disability have been made. The operational definitions of the IOM categories of FASD are practical and reliable, and produce specific diagnoses from applying criteria from all three domains of variables: physical, cognitive/developmental, and measures of alcohol quantity, frequency, and timing (QFT). Most of the dysmorphology traits are now consistently quantified and allow comparison and correlation with many variables across the domains. Active outreach in schools ensures that selectivity and/or omission of cases is minimized. Using these methods consistently provides opportunities to compare FASD across populations and examination of relative risk from particular drinking styles, exposures, health and environmental conditions.

Rates and Prevention

The rate of FAS remains high in this community, and the higher rates in the rural, lower SES areas continue. The total rate of FASD found in this sample is 135.1 to 207.5 per 1,000 or 13.6 % to 20.8%. It is obvious from this fourth study in this community that identifying the substantial FASD problem through research and limited prevention efforts for three years prior to the conception of this cohort of children did not reduce problematic maternal drinking among the highest risk individuals. Substantial improvements are needed in specific socio-economic conditions and drinking sub-culture patterns that have led to the problem. Also a massive, comprehensive prevention program may be needed to target long term practices and to leverage change in the highest risk elements of the population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse, and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grants RO1 AA09440, R01 AA11685, and RO1/UO1 AA01115134, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD). Faye Calhoun, D.P.A., Kenneth Warren, Ph.D., and T-K Li, M.D. of NIAAA have provided intellectual guidance, participated in, and supported the South African studies of FASD in a variety of ways since 1995. Our deepest thanks are extended to: Mayor Herman Bailey of the study community, the principals and the staffs of the 13 primary schools, and to many in the community who have graciously hosted and assisted in the research process over the years. Jo Carothers and Julie Hasken contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Protocols and consent forms were approved by: The University of New Mexico (UNM) 09-97-90-9805, 01-93-86-9808R; UNM School of Medicine, HRRC # 96-209, and 06-199;The University of Cape Town, #101/2004U and Stellenbosch University, Faculty of Health Sciences, # N06/07/129. Active consent for children to participate in all phases of this study was obtained from parents or other legal guardians. Mothers interviewed for maternal risk factors also provided a separate consent for the interview process.

REFERENCES

- Aase JM. Clinical recognition of FAS: difficulties of detection and diagnosis. Alcohol Health Res World. 1994;18:5–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adèr HJ, Mellenbergh GJ, Hand DJ. Advising on Research Methods: a Consultant's Companion. Johannes van Kessel Publishing; Huizen, The Netherlands: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alvik A, Haldorsen T, Lindemann R. Alcohol consumption, smoking and breastfeeding in the first six months after delivery. Acta paediatrica. 2006;95:686–693. doi: 10.1080/08035250600649266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EM. Conceiving Risk, Bearing Responsibility: Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and the Diagnosis of Moral Disorder. The Johns Hopkins Press; Baltimore, Maryland: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ, Clarren SK. Diagnosing the full spectrum of fetal alcohol-exposed individuals: introducing the 4-digit diagnostic code. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:400–410. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J, Floyd LL, Weber MK. Guidelines for identifying and referring persons with fetal alcohol syndrome. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-11):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DVM. Test of the Reception of Grammar (TROG) 2nd edition University of Manchester; Manchester: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cigarette Smoking among Adults-United States, 2004. MMWR. 2005;54(44):1121–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudley AE, Conry J, Cook JL, Loock C, Rosales T, LeBlanc N. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. CMAJ. 2005;172(5 Suppl):S1–S21. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarren SK, Randels SP, Sanderson M, Fineman RM. Screening for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in primary schools: a feasibility study. Teratology. 2001;63:3–10. doi: 10.1002/1096-9926(200101)63:1<3::AID-TERA1001>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crome IB, Glass Y. The DOP system: A manifestation of social exclusion. A personal commentary on “alcohol consumption amongst South African workers.”. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:207–208. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxford J, Viljoen D. Alcohol consumption by pregnant women in the Western Cape. S Afr Med J. 1999;89:962–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki DM, Russell M, Cooper ML, Salter D. Five-year reliability of self-reported alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol. 1990;51:68–76. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AG, Dean JA, Coulambier D, Brendel KA, Smith DC, Burton AH, Dickers RC, Sullivan K, Faglen RF, Arnir TG. Epi Info, Version 6: A Word Processing Data Base, and Statistical Program for Epidemiology in Microcomputers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan JH, Chiodo LM, Sokol RJ, Janisse J, Ager JW, Greenwald MK, Delaney Black V. A 14-Year Retrospective Maternal Report of Alcohol Consumption in Pregnancy Predicts Pregnancy and Teen Outcomes. Alcohol. 2010;44:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, Kodituwakku P, Gossage JP, Trujillo PM, Buckley DG, Miller J, Aragon AA, Khaole N, Viljoen DL, Jones KL, Robinson LK. A Practical Clinical Approach to Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: clarification of the 1996 Institute of Medicine Criteria. Pediatrics. 2005;115:39–47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Coordinating Committee on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (ICCFASD) Consensus Statement on Recognizing Alcohol-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND) in Primary Health Care of Children. ICCFASD; Rockville, MD: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW. Recognition of the Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in early infancy. Lancet. 1973;2:999–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Graves K. An alternative to standard drinks as a measure of alcohol consumption. J Subst Abuse. 2000;12:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Graves K. Pre-pregnancy drinking: how drink size affects risk assessment. Addiction. 2001;96:1199–1209. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.968119912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Kerr WC. Accuracy of photographs to capture respondent-defined drink size. J Stud Alc Drugs. 2008;69:605–610. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaole NCO, Ramchandani VA, Viljoen DL, Li TK. A Pilot study of alcohol exposure and pharmacokinetics in women with or without children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:503–508. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh089. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC. Enhancing the self-report of alcohol consumption in the community: two questionnaire formats. Amer J Pub Health. 1994;84:294–296. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L. Alcohol Consumption Amongst South African Farm Workers: a Challenge for Post-apartheid Health Sector Transformation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:199–226. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager A. White liquor hits black lives: meaning of excessive liquor consumption in South Africa in the second half of the twentieth century. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:735–751. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Brooke LE, Gossage JP, Croxford J, Adnams C, Jones KL, Robinson LK, Viljoen D. The epidemiology of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in a South African community in the Western Cape Province. Am J Pub Health. 2000;9012:1905–1912. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Brooke LE, Gossage JP, Snell C, Hendricks L, Croxford J, Marais AS, Viljoen DL. Maternal risk factors for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: a population-based study. Am J Pub Health. 2005;95:1190–1199. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.037093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, White-Country M, Goodhart K, DeCoteau S, Trujillo PM, Kalberg WO, Viljoen DL, Hoyme HE. Alcohol consumption and other maternal risk factors for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome among three distinct samples of women before, during, and after pregnancy: the risk is relative. Am J Med Genet Sem in Med Genet. 2004;127C:10–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, Adnams M, Hoyme HE, Jones KL, Robinson LK, Khaole NC, Snell C, Kalberg WO, Hendricks L, Brooke L, Stellavato C, Viljoen DL. The epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome and partial FAS in a South African community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Fiorentino D, Coriale G, et al. Prevalence of children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in communities near Rome, Italy: rates are substantially higher than previous estimates. Int J Env Res Pub Health. 2011a;8:2331–2351. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8062331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Tabachnick BG, Robinson LK, et al. Maternal risk factors predicting child physical characteristics and dysmorphology in Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Partial Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011b;119:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Robinson LK, Buckley DG, Manning M, Hoyme HE. The prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on in-school studies. Devel Dis Res Rev. 2009;15:176–192. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.68. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Miller JH, Goodhart KA, et al. Enhanced case management to prevent Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in northern plains communities. Mat Child Health J. 2008a;12:747–759. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais A-S, et al. Maternal risk Factors for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Partial Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in South Africa: a third study. Alcoh Clin Exp Res. 2008b;32:738–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Fiorentino D, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Hoyme HE, Robinson LK, Coriale G, Jones KL, del Campo M, Tarani L, Romeo M, Kodituwakku PW, Deiana L, Buckley D, Ceccanti M. The epidemiology of FASD in a province in Italy: prevalence and characteristics of children in a random sample of schools. Alcohol Clin Exper Res. 2006;30:1562–1575. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP. Estimating the prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: a summary. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH, Bennetts AL. Alcohol policy and public health in South Africa. Oxford University Press; Cape Town: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Petković G, Barišić I. FAS prevalence in a sample of urban schoolchildren in Croatia. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;29:237–41. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J. Research Supplement No.1: the 1979 British standardisation of the standard Progressive Matrices and Mill Hill Vocabulary Scales, together with comparative data from earlier studies in the UK, US, Canada, Germany and Ireland. Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 1981. Manual for Raven's Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, London L, Olorunju SA, Matjila MJ, Davids AS, Rendall-Mkosi KM. Predictors of risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancies among women in an urban and a rural area of South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Agrawal S, Annis H, Ayala-Velazquez H, Echeverria L, Leo GI, Rybakowski JK, Sandahl C, Saunders B, Thomas S, Zioikowski M. Cross-cultural evaluation of two drinking assessment instruments: alcohol timeline followback and inventory of drinking situations. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36:313–331. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinker's reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol RF, Clarren SK. Guidelines for use of terminology describing the impact of prenatal alcohol on the offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:597–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS 19.0 . Command Syntax Reference. SPSS Inc.; Chicago Ill. Statistics South Africa: 2010. [January 15, 2012]. Community Survey 2007. [Statistics South Africa website]. 2007.Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/community_new/content.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F, editors. Institute of Medicine. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: diagnosis, epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan WC. A note on the influence of maternal inebriety on the offspring. J Mental Science. 1899;45:489–503. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Firth Edition Pearson Education, Inc.; Boston: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Urban M, Chersich MF, Fourie LA, Chetty C, Olivier L, Viljoen D. Fetal alcohol syndrome among grade 1 schoolchildren in Northern Cape Province: prevalence and risk factors. South Africa Med J. 2008;98:877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen DL, Croxford J, Gossage JP, May PA. Characteristics of mothers of children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in the Western Cape Province of South Africa: a case control study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:6–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen DL, Gossage JP, Adnams C, Jones KL, Robinson LK, HE, Snell C, Khaole N, Asante KK, Findlay R, Quinton B, Brooke LE, May PA. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome epidemiology in a South African community: a second study of a very high prevalence area. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:593–604. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren K, Floyd L, Calhoun F, et al. Consensus statement on FASD. National Organization of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome; Washington, D.C.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Third Ed. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wurst FM, Kelso E, Weinmann W, Pragst F, Yegles M, Sundström Poromaa I. Measurement of direct ethanol metabolites suggests higher rate of alcohol use among pregnant women than found with the AUDIT--a pilot study in a population-based sample of Swedish women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:407, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]