Abstract

People with mental illness have long experienced prejudice and discrimination. Researchers have been able to study this phenomenon as stigma and have begun to examine ways of reducing this stigma. Public stigma is the most prominent form observed and studied, as it represents the prejudice and discrimination directed at a group by the larger population. Self-stigma occurs when people internalize these public attitudes and suffer numerous negative consequences as a result. In this article, we more fully define the concept of self-stigma and describe the negative consequences of self-stigma for people with mental illness. We also examine the advantages and disadvantages of disclosure in reducing the impact of stigma. In addition, we argue that a key to challenging self-stigma is to promote personal empowerment. Lastly, we discuss individual and societal level methods for reducing self-stigma, programs led by peers as well as those led by social service providers.

Keywords: Self-stigma, stigma reduction, mental illness, empowerment

In making sense of the prejudice and discrimination experienced by people with mental illness, researchers have come to distinguish public stigma from self-stigma 1 (Corrigan, 2005). Public stigma is what commonly comes to mind when discussing the phenomenon and represents the prejudice and discrimination directed at a group by the population. Public stigma refers to the negative attitudes held by members of the public about people with devalued characteristics. Self-stigma occurs when people internalize these public attitudes and suffer numerous negative consequences as a result 2. In this article, we seek to more fully define self-stigma, doing so in terms of a stage model. We will argue that a key to challenging self-stigma is to promote personal empowerment. One way to do this is through disclosure, the strategic decision to let others know about one’s struggle towards recovery. Then, we will discuss individual and societal level methods for reducing self-stigma.

Defining Self-Stigma

While acknowledging the role of societal and interpersonal processes involved in stigma creation, social psychologists’ study stigma as it related to internal and subsequent behavioral processes that can lead to social isolation and ostracism3. Stereotypes are the way in which humans categorize information about groups of people. Negative stereotypes, such as notions of dangerousness or incompetence, often associated with mental illness, can be harmful to people living with mental illnesses. Most people have knowledge of particular stereotypes because they develop from and are defined by societal characterizations of people with certain conditions. Although broader society has defined these stereotypes, people may not necessarily agree with them. People who agree with the negative stereotypes develop negative feelings and emotional reactions; this is prejudice. For example, a person who believes that people with schizophrenia are dangerous may ultimately describe feeling fearful of those with serious mental illness. From this emotional reaction comes discrimination, or the behavioral response to having negative thoughts and feelings about a person in a stigmatized outgroup. A member of the general public may choose to remain distant from a person with mental illness because of their fear (prejudice) and belief (stereotype) that the person with mental illness is dangerous.

Individuals who live with conditions such as schizophrenia are also vulnerable to endorsing stereotypes about themselves, self-stigma. It is comprised of endorsement of these stereotypes of the self (e.g. “I am dangerous”), prejudice (e.g. “I am afraid of myself”), and resulting self-discrimination (e.g. self-imposed isolation). Once a person internalizes negative stereotypes, they may have negative emotional reactions. Low self-esteem and poor self-efficacy are primary examples of these negative emotional reactions 4. Self-discrimination, particularly in the form of self-isolation, has many pernicious effects leading to decreased healthcare service use, poor health outcomes, and poor quality of life 5,6. Poor self-efficacy and low self-esteem have also been associated with not taking advantage of opportunities that promote employment and independent living7. Link et al.8 called this modified labeling theory; contrasting classic notions of the label (Gove, 1980, 1982)9,10, Link noted people who internalize the stigma of mental illness worsen the course of their illness because of the harm of the internalized experience per se. Self-stigmatization diminishes feelings of self-worth such that the hope in achieving goals is undermined. Thus, the harm of self-stigma manifests itself-through an intra-personal process, and ultimately, through poor health outcomes and quality of life 2,4.

A Stage Model of Self-Stigma

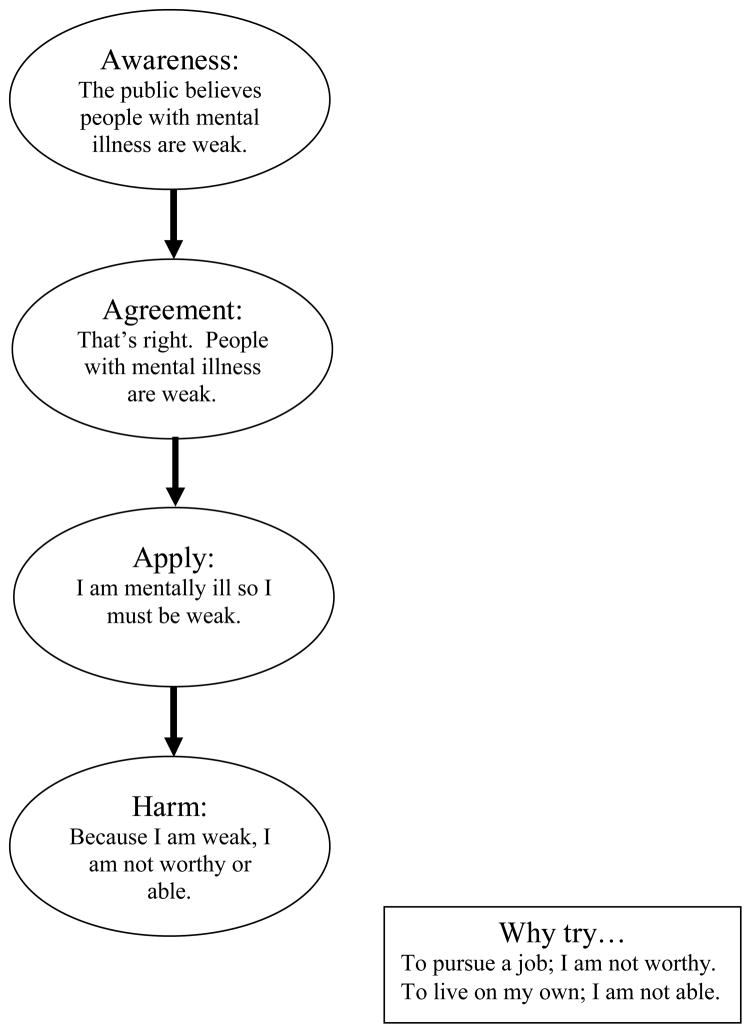

Self-stigma has often been equated with perceived stigma, a person’s recognition that the public holds prejudice and will discriminate against them because of their mental illness label 7. In particular, perceived devaluation and discrimination is thought to lead to diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy. We believe this to actually be the first stage of a progressive model of self-stigma (see Figure 1). As such, we see the process of internalizing public stigmas as occurring through a series of stages that successively follow one another 2,4,10,11. In the general model, a person with an undesired condition is aware of public stigma about their condition (Awareness). This person may then agree that these negative public stereotypes are true about the group (Agreement). Subsequently, the person concurs that these stereotypes apply to him/herself (Application). This may lead to harm, to significant decreases in self-esteem and self-efficacy. Unlike other research on self-stigma 13,14 the stage model shows pernicious effects of stigma on the self do not occur until later stages. Not until the person applies the stigma, does harm to self-esteem or self-efficacy occur.

Figure 1.

The Stage Model of Self Stigma

One of the challenges of a stage model of self-stigma is sorting out the effects of later stages from those of depression which is frequently experienced among people with serious mental illness 15. Other staged models of behavior suggest any individual stage is most strongly influenced by the immediately preceding one16. Thus, in order to fully understand stigma’s contribution to poor health outcomes, research must crosswalk specific stages with common antecedents of poor outcomes such as depressive symptoms. In this way, the effects of internalized stigma on self-esteem can be partialled out from other causes of depression.

The Why Try Effect

A related consequence of self-stigmatization is what has been called the “why try” effect, in which self-stigmatization interferes with life goal achievement11. Self stigma functions as a barrier to achieving life goals. However, self-esteem and self-efficacy can reduce the harmful results of self-stigma. . Diminished self-esteem leads to a sense of being less worthy of opportunities that undermine efforts at independence like obtaining a competitive job.

“Why should I seek a job as an accountant? I am not deserving of such an important position. My flaws should not allow me to take this kind of a job from someone who is more commendable.”

Alternatively, decrements to self-efficacy can lead to a why try outcome based on the belief the person is not capable of achieving a life goal.

“Why should I attempt to live on my own? I am not able to do such independence. I do not have the skills to manage my own home.”

“Why try” is a variant of modified labeling theory 8, that the social rejection linked to stigmatization contributes to low self-esteem. Modified labeling theory also suggests avoidance as a behavioral consequence of devaluation. When people perceive devaluation, they may avoid situations where public disrespect is anticipated.

Challenging Self-Stigma

There is a paradox to self-stigma 12. Some people with mental illness internalize it and suffer the harm to self-esteem, self-efficacy, and lost goals. Many others, however, seem oblivious to its effects and report no pain. Yet, a third group is especially interesting; people who seem to report righteous indignation at the injustice of stigma. It is this third group that might suggest an antidote to self-stigma: personal empowerment. Empowering individuals seems to be an effective way of reducing self-stigmatization, encourage people to believe they can achieve their life goals, and circumvent further negative consequences that result from self-stigmatizations. Empowerment is, in a sense, the flip side of stigma, involving power, control, activism, righteous indignation, and optimism. Investigations have shown empowerment to be associated with high self-esteem, better quality of life, increased social support, and increased satisfaction with mutual-help programs17,18,19. Thus, empowerment is the broad manner by which we can reduce stigma. In the remainder of the article, we describe the specific mechanisms that are involved with empowering individuals as ways to decrease self-stigma.

Disclosure: The First Step

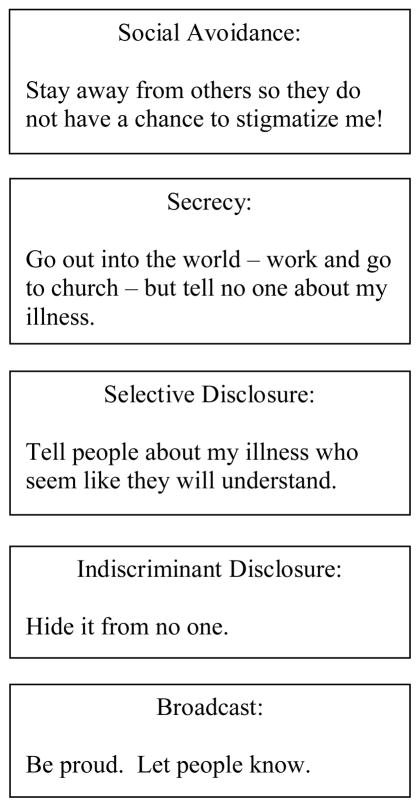

Many people deal with self-stigma by staying in the closet; they are able to shelter their shame by not letting other people know about their mental illness. One way to promote stigma and counter the shame is to come out; to let other people know about the person’s psychiatric history. Research has interestingly shown ‘coming out of the closet’ with mental illness is associated with decreased negative effects of self-stigmatization on quality of life, thereby encouraging people to move towards achieving their life goals 20. When people are open about their condition, worry and concern over secrecy is reduced, they may soon find peers or family members who will support them even after knowing their condition, and they may find that their openness promotes a sense of power and control over their lives 21. Still, being open about one’s condition can have negative implications. Openness may bring about discrimination by members of the public, any relapses may be more widely known than preferred and therefore more stressful, and in some cases, disclosure may be more isolating. For example, in India, documentation of mental illness is grounds for divorce, a situation that some would consider a form of institutionalized stigma 22,23. A person with mental illness in India may feel doubly stressed by the threat of divorce and further public discrimination. Deciding to disclose is ultimately very personal decision, closely tied to the cultural context that requires thorough consideration of the potential benefits and consequences.

Coming out is not a black or white decision. There are strategies that vary in risk for handling disclosure which are summarized in Figure 2 24,25. At the most extreme, people may stay in the closet through social avoidance. This means keeping away from situations where people may find out about one’s mental illness. Instead, they only associate with other persons who have mental illness. It is protective (no one will find out the shame) but obviously also very restrictive. Others may choose not to avoid social situations but instead to keep their experiences a secret. An alternative version of this is selective disclosure. Selective disclosure means there is a group of people with whom private information is disclosed and a group from whom this information is kept secret. While there may be benefits of selective disclosure such as an increase in supportive peers, there is still a secret that could represent a source of shame. People who choose indiscriminant disclosure abandon the secrecy. They make no active efforts to try to conceal their mental health history and experiences. Hence, they opt to disregard any of the negative consequences of people finding out about their mental illness. Broadcasting one’s experience means educating people about mental illness. The goal here is to seek out people to share past history and current experiences with mental illness. Broadcasting has additional benefits compared to indiscriminant disclosure. Namely, it fosters their sense of power over the experience of mental illness and stigma.

Figure 2.

A hierarchy of disclosure strategies

Methods of Reducing Stigma

There are other strategies that people living with mental illness can use to cope with the negative consequences of self-stigmatization. A caution needs to be sounded first. In trying to help people learn to overcome self-stigma, advocates need to make sure they do not suggest stigma is the person’s fault, that having self-stigma is some kind of “flaw” like other psychiatric symptoms which the person needs to correct. Stigma is social injustice and an error of society. Hence, eradicating it is the responsibility and should be the priority of that society. In the meantime, people with mental illness may wish to learn ways to live with or compartmentalize that stigma. But curing it lies with the community in which one lives. Hence, erasing public stigma may be a broad based fix of the stigma problem. What we broach here are more narrowly focused efforts to help people who are bothered by internalized stigma.

Manualized approaches to self-stigma reduction for people with mental illnesses are in development. One promising approach is the “Ending Self-Stigma” intervention 26 which uses a group approach to reduce self-stigmatization. The intervention meets as a group for 9 sessions with materials covering education about mental health, cognitive behavioral strategies to impact the internalization of public stigmas, methods to strengthen family and community ties, and techniques for responding to public discrimination. The cognitive behavioral strategies rest on insights from cognitive therapy 27 that frame self-stigma as irrational self-statements ( for example “I must be a stupid person because I get depressed.”) which the person seeks to challenge (“Most other people do not think depressed people are stupid.”) These kinds of challenges lead to counters -- pithy statements people might use next time they catch themselves self-stigmatizing. “There I go again. Just because I got depressed last fall does not mean I am stupid and incapable of handling a job. I have struggles just like everyone else.” A pilot study of the intervention showed that internalized stigma was reduced and perceived social support increased after participation in the weekly intervention 26.

A good example of a societal level approach that may also benefit the individual is the “In Our Own Voice” program developed by the National Alliance on Mental Illness in the United States. This intervention involves a manualized group approach for targeted groups of the general population. Testimonials by people with mental illness are the key to stigma reduction in this program. Participants of the intervention can be health care professionals, church congregations, students, etc. Research has shown its effectiveness in reducing negative attitudes towards people with mental illness in long and short versions 11. If programs such as these help to reduce public stigmas around mental illness, possible prejudice that a person with mental illness perceive and internalize would be reduced, thus indirectly impacting self-stigma. In addition, the people providing testimonials as part of the intervention feel empowered by the activist role they play in advocating for themselves, thereby reducing self stigma as the program is implemented.

Peer Support

Consumer-operated programs offer another way for people with serious mental illness to enhance their sense of empowerment 28. Groups like these provide a range of services including support for those who are just coming out, recreation and shared experiences which foster a sense of community within a larger hostile culture, and advocacy/political efforts to further promote group pride 28. Several forces have converged over the past century to foster consumer-operated services for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Some reflect dissatisfaction with mental health services that disempower persons by providing services in restrictive settings. Others represent a natural tendency of persons to seek support from others with similar problems. Recently, a variety of consumer-operated service programs have developed including: drop in centers, housing programs, homeless services, case management, crisis response, benefit acquisition, anti-stigma services, advocacy, research, technical assistance, and employment programs 28,30. Results of a qualitative evaluation of consumer operated programs showed that participants in these programs reported improvements in self-reliance and independence; coping skills and knowledge; and feelings of empowerment 30. Future research needs to isolate the active ingredients of consumer-operated services that lead to positive change.

Conclusions

Stigma is a societal creation, what social psychologists have come to describe as prejudice and discrimination. Unfortunately, some people with serious mental illness internalize the stigma and suffer significant blows to self-esteem and self-efficacy. Self-stigma, however, is not an inevitable curse. People in a stigmatized group do not necessarily turn that stigma onto themselves. Consider research about racism affecting the African American community. Classic psychological models believed African Americans to have lower self-esteem than White Americans because the former internalized the biases and prejudices about them that dominated in the culture 31,32. Research consistently fails to show this, and in fact, may suggest the obverse; African Americans may have higher self-esteem than White Americans 33,34,35,36,37,38. How can this be? African Americans will report they are aware of White Americans prejudice but do not believe it actually applies to themselves. In fact, many African Americans report White Americans ignorance can be a personal rallying cry for their personal sense of empowerment and a call for their community.

The lesson seems to apply to self-stigma for mental illness too. Internalizing prejudice and discrimination is not a necessary consequence of stigma. Many people recognize stigma as unjust and, rather than being swept by it, take it on as a personal goal to change. Many others are unaware or unmotivated by the phenomenon altogether. There are those, however, who seem to apply the prejudice to themselves and suffer lessened self-esteem and self-efficacy. These people might benefit from structured programs to learn to challenge the irrational statements that plague their self-identity. They might benefit from joining groups of peers who have successfully tackled the stigma. They may benefit from a strategic program to come out about their stigma. Research needs to continue to identify and evaluate programs that promote empowerment at the expense of self-stigma.

Acknowledgments

Funding and support: This work was supported in part by US NIMH 08598-01.

Contributor Information

Patrick W. Corrigan, Illinois Institute of Technology

Deepa Rao, University of Washington.

References

- 1.Corrigan PW. On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrigan PW, Watson A, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(9):875–884. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phelan JC, Link BG, Dovidio JF. Stigma and prejudice: one animal or two? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):479–481. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Link B. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Link B, Cullen F, Struening E, et al. A Modified Labeling Theory Approach to Mental Disorders: An Empirical Assessment American Sociological Review. 1989;54(3):400–423. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gove WR. Labelling and mental illness: A critique. In: Gove WR, editor. The labeling of deviance: Evaluating a perspective. 2. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. pp. 53–99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gove WR. The current status of the labeling theory of mental illness. In: Gove WR, editor. Deviance and Mental Illness. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrigan P, Larson J, Rusch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler A, Hokanson J, Flynn H. A comparison of self-esteem lability and low trait self-esteem as vulnerability factors for depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psycholology. 1994;66:166–177. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perz C, DiClemente C, Carbonari J. Doing the right thing at the right time? The interaction of stages and processes of change in successful smoking cessation. Health Psycholology. 1996;15(6):462–468. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.6.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrigan PW, Faber D, Rashid F, et al. The construct validity of empowerment among consumers of mental health services. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;38:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers E, Chamberlin J, Ellison M. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:1042–1047. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers ES, Ralph RO, Salzer MS. Validating the Empowerment Scale With a Multisite Sample of Consumers of Mental Health Services. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:933–936. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.9.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrigan P, Morris S, Larson J, et al. Self-stigma and coming out about one’s mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38:259–27. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corrigan P, Roe D, Tsang H. Challenging the Stigma of Mental Illness. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thara R, Kamath S, Kumar S. Women with schizophrenia and broken marriages--doubly disadvantaged? Part I: Patient perspective. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;49(3):225–232. doi: 10.1177/00207640030493008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thara R, Kamath S, Kumar S. Women with schizophrenia and broken marriages--doubly disadvantaged? Part II: Family perspective. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;49(3):233–240. doi: 10.1177/00207640030493009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan PW, Lundin RK. Don’t Call Me Nuts! Coping with the Stigma of Mental Illness. Tinley Park, IL: Recovery Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman NJ. Return to sender: Reintegrative stigma-management strategies of expsychiatric patients. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1993;22:295–330. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucksted A, Drapalski A, Calmes C, et al. Ending Self-Stigma: Pilot evaluation of a new intervention to reduce internalized stigma among people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2011 Summer;35(1):51–4. doi: 10.2975/35.1.2011.51.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck Aaron T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press Inc; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clay S, Schell B, Corrigan PW. On our own, together: Peer programs for people with mental illness. Vanderbilt University Press; Nashville: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kates SM, Belk RW. The meanings of lesbian and gay pride day: Resistance through consumption and resistance to consumption. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 2001;30 (August):392–429. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Tosh L, del Vecchio P. Consumer/survivor-operated self-help programs: A technical report. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoelter JW. Factorial invariance and self-esteem: Reassessing race and sex differences. Social Forces. 1983;61:834–846. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen GF, White CS, Gelleher JM. Ethnic status and adolescent self evaluations: An extension of research on minority self-esteem. Social Problems. 1982;30:226–239. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Porter JR, Washington RE. Annual Review of Sociology. Palo Alto, Calif: Annual Reviews; 1979. Black Identity and Self-Esteem: A Review of Studies of Black Self-Concept, 1968–1978; pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verkuyten M. Self-esteem among ethnic minority youth in western countries. Social Indicators Research. 1994;32:21–47. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verkuyten M. Self-esteem, self-concept stability, and aspects of ethnic identity among minority and majority youth in the Netherlands. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wylie R. The self-concept. Vol. 2. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]