Abstract

Background:

One way to gain insight into the pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is to study the immunologic changes that occur with exacerbation. This study describes the immunologic changes during CRS exacerbation

Methods:

We performed a prospective study to investigate the immunologic changes seen during exacerbation of CRS with nasal polyposis. We recruited adult subjects who met clinical criteria for CRS with sinus CT scan within the past 5 years with Lund-Mackay score of >5 and nasal polyps. Subjects underwent a baseline visit with collection of nasal secretion and nasal wash. With acute worsening of symptoms, subjects underwent 6 near-consecutive-day collections and one follow-up collection 2 weeks later. IL-6, IL-33, eosinophil major basic protein (MBP), eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and uric acid were measured on the nasal samples from each visit.

Results:

A total of 10 subjects were recruited and 9 had acute worsening of CRS during the study period. Eight of the nine subjects were women and ages ranged from 26 to 56 years. At baseline, most inflammatory parameters were low and eight of the nine subjects were on intranasal corticosteroids. Compared with baseline measurements, IL-6, MBP, MPO, EDN, and uric acid were significantly elevated during CRS exacerbation. Levels of IL-6 and MBP (r = 0.47) levels as well as IL-6 and MPO (r = 0.75) were both significantly correlated (p < 0.01).

Conclusion:

Prospective study of CRS exacerbations is feasible and provides insights into the immunologic mechanisms of CRS.

Keywords: Chronic sinusitis, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, eosinophil major basic protein, exacerbation, interleukin-6, interleukin-33, myeloperoxidase, nasal polyposis, nasal secretion, uric acid, viral upper respiratory tract infection

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is a common and debilitating problem that involves inflammation of the mucosal surfaces lining the nose and sinuses, leading to persistent symptoms of nasal congestion, nasal discharge, loss of smell, and facial pressure.1 Unfortunately, many individuals with CRS continue to suffer despite use of currently available treatments.2,3 Immunologic mechanisms of CRS are not fully understood; a growing body of evidence suggests that CRS is heterogenous.4,5 One way to address these major gaps in our knowledge is to study the immunologic changes that occur with disease exacerbation. The objective of this study was to pilot test a model to study local immunologic changes that occur during natural exacerbations of CRS. To our knowledge, this is the first article describing immunologic changes during a CRS exacerbation using several prospective measurements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective study of individuals with CRS with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP). Inclusion criteria were (1) aged ≥18 years; (2) meet clinical definition of CRS, which is 12 weeks with at least two of the major criteria for diagnosis (nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, facial congestion, facial pain/pressure/fullness, or a decrease in smell) within the past 24 months; (3) availability of a sinus CT scan within the past 5 years with a Lund-Mackay score of >56; (4) documentation of nasal polyps within the past 3 years. Exclusion criteria were (1) cystic fibrosis, (2) primary ciliary dyskinesia, (3) a primary immune deficiency disorder, (4) any cigarette smoking in the past year, (5) oral corticosteroids in the past 2 weeks before enrollment, or (6) intramuscular corticosteroids in the past 6 weeks before enrollment. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Individuals meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria underwent baseline assessments (VBL), which included completion of a 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-22),7 recording of all medications, nasal secretion, and nasal wash. Nasal secretions were obtained from the right nasal cavity by using a sterile sinus secretion collector (Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville, FL). The secretions were extracted by mixing with a threefold volume of 0.9% sterile NaCl. Nasal washes were performed by instilling 5 mL of isotonic saline (via syringe) in the left nostril followed by a collection into a sterile glass beaker designed for collection of nasal washes.

Participants were instructed to contact the research team if their CRS symptoms worsened acutely. Participants then provided daily nasal secretions and washes for 6 nearly consecutive days (visits 0–5 [V0–V5]) and one follow-up visit 2 weeks after the first acute visit (V6). Participants completed an SNOT-22 at the VBL, V0, V5, and V6 based on recall of the previous 7 days of symptoms.7

The levels of IL-6, IL-33, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) were measured by commercial ELISA kits (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The uric acid level was measured by Amplex Red uric acid assay kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Major basic protein (MBP) and eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN) were measured by in-house radioimmunoassay systems.8

Differences between baseline measurements and each time point were calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, with p < 0.05 considered significant (JMP, 9.0.1; SAS, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

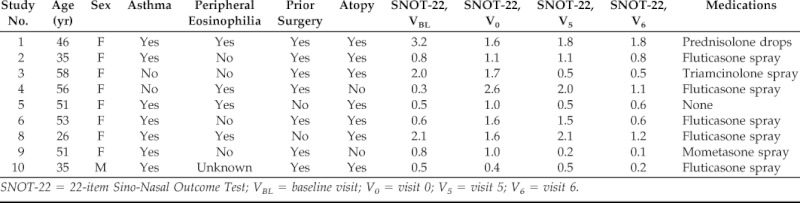

Ten subjects were enrolled in January and February of 2012. Nine subjects presented for worsening of their symptoms between February and May of 2012. Table 1 describes the age, gender, SNOT-22 scores, and current medications for all nine participants who presented for worsening symptoms. In addition, from medical record review, we determined if the subjects had asthma, peripheral eosinophilia >0.5 × 109/L (based on maximum value reported in the medical record), previous sinus surgery, or atopy (based on positive skin-prick or serum-specific IgE tests). Only two of the participants (2 and 9) had a history of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease and one had a diagnosis of allergic fungal sinusitis.2 We further analyzed the results of the SNOT-22 questionnaires and found that changes between V0 and VBL were significantly increased for “need to blow nose” (2.33 versus 1.33; p = 0.03) and were increased, although not significantly in questions regarding nasal symptoms (runny nose, 2.00 versus 1.33; postnasal discharge, 2.89 versus 2.22; and thick nasal discharge, 2.25 versus 1.89).

Table 1.

Description of research participants

SNOT-22 = 22-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test; VBL = baseline visit; V0 = visit 0; V5 = visit 5; V6 = visit 6.

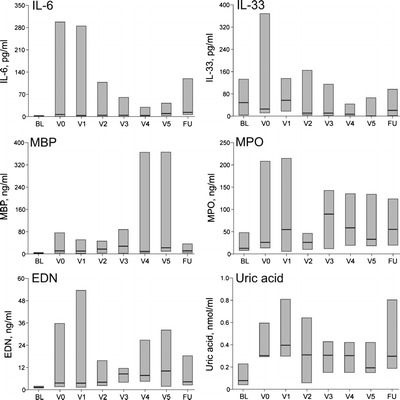

Figure 1 presents the changes over time in the immunologic parameters as composite values for all nine participants, presented as median and 25–75% quartiles. At the baseline, the levels of inflammatory parameters were relatively low, even though all the participants carried a diagnosis of CRSwNP. Compared with baseline measurements, IL-6, MBP, MPO, EDN, and uric acid were significantly elevated during CRS exacerbation (Fig. 1). The levels of MPO and EDN appeared to show peaks early and late in exacerbation, and the uric acid remained elevated throughout the observation period. The levels of IL-6 and MBP as well as IL-6 and MPO showed significant correlation (r = 0.47 and 0.75, respectively; p < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Immunologic measurements during chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) exacerbation. IL-33 and major basic protein (MBP) were measured in nasal secretions and IL-6, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (EDN), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and uric acid were measured in nasal washes. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

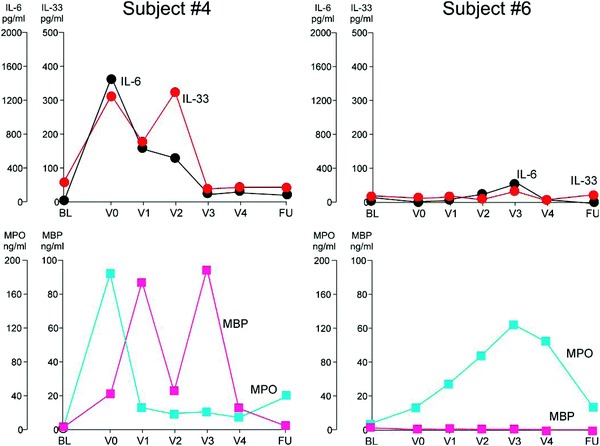

The immunologic patterns observed in participants 4 and 6 are of special interest because both met the minimum decrease in the mean score of the SNOT-22 of >0.8 at V0 compared with VBL (displayed in Fig. 2). Participant 4's SNOT-22 score never returned to baseline and showed a pattern of increased IL-6, IL-33, MPO, and MBP, and participant 6's SNOT-22 returned to baseline and showed a pattern of increased MPO only.

Figure 2.

Individual participant immunologic measurements during chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) exacerbation.

DISCUSSION

This study shows the feasibility of prospectively evaluating participants with CRS exacerbations. In our study, two of the nine participants reporting worsening of their CRS symptoms had significant decreases in their SNOT-22 scores; both participants showed marked, although different, immunologic changes as measured in nasal secretions and washes. When considering all patients with self-reported disease exacerbation, we found significantly elevated levels of IL-6, MBP, MPO, EDN, and uric acid during disease exacerbation compared with baseline. To our knowledge, this is the first description of immunologic changes in individuals with CRS comparing baseline with disease exacerbation using serial immunologic measurements.

It is possible that the increased IL-6 response seen in our study is consistent with onset of a viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Elevation of IL-6 in nasal irrigation fluid of healthy individuals has previously been reported during experimental rhinovirus infection.9 Epidemiological data from Olmsted County documented CRS disease exacerbations during the winter season during which viral infections are known to be prevalent.10 Imaging studies of acute rhinosinusitis secondary to viral URTI confirm the ability of viruses to elicit sinus mucosal swelling.11–13 In addition, blowing the nose has been previously shown to propel viral particles into the sinuses.14 Identification of virus in surgical specimens and by inferences from studies using animal models has also been reported.15–20

A recent study identified activation of IL-6 (and a possible signaling defect in the IL-6 pathway) in patients with CRS and nasal polyps compared with normal controls.21 These findings suggest a host characteristic, when coupled with an environmental exposure such as viral URTI that promotes IL-6 production, could potentially explain a key underlying mechanism of CRS exacerbations. One could further speculate that an immune signature that includes IL-33 and MBP may be an eosinophilic signature (as best shown by the pattern seen in participant 4) as opposed to a neutrophilic signature (as best shown in participant 6).

There are several limitations that must be considered. First, the reproducibility of the collection methods requires further testing, especially with regard to the stability of the baseline measurement variability. Second, the number of subjects is small for this pilot study, and we did not include participants without nasal polyps (an important CRS subtype) or a normal control group to see if these immunologic changes are unique to CRSwNP patients. Third, we did not measure virus, bacteria, or fungi for this study, all of which may change in interesting ways during a CRS exacerbation. It would be important in the future to correlate the magnitudes and characteristics of the immune responses with the microbial species that cause exacerbation. Finally, all of the participants except one were taking topical corticosteroid medications, which could influence the immunologic patterns we measured. Topical corticosteroid may also explain relatively low levels of inflammatory parameters at the baseline (i.e., VBL).

In conclusion, we have provided evidence of the potential usefulness in studying the immunologic changes during CRS exacerbation, a study model that may allow for a better understanding of the heterogeneity of CRS as well as shed light on the immunologic mechanisms responsible for the transition from acute to chronic inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Kay Bachman, R.N., and Diane Squillace, B.S., for their technical expertise.

Footnotes

Funded by NIH AI49235

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare pertaining to this article

REFERENCES

- 1. Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: Establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114(suppl 6):155–212, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhattacharyya N. Contemporary assessment of the disease burden of sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy 23:392–395, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soler ZM, Mace JC, Litvack JR, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis, race, and ethnicity. Am J Rhinol Allergy 26:110–116, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Payne SC, Borish L, Steinke JW. Genetics and phenotyping in chronic sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128:710–720, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hsu J, Peters AT. Pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyp. Am J Rhinol Allergy 25:285–290, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 31(4):183–184, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG, Jr, Richards ML. Psychometric and clinimetric validity of the 20-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (SNOT-20). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126:41–47, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abu-Ghazaleh RI, Dunnette SL, Loegering DA, et al. Eosinophil granule proteins in peripheral blood granulocytes. J Leukocyte Biol 52:611–618, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu Z, Tang W, Ray A, et al. Rhinovirus stimulation of interleukin-6 in vivo and in vitro. Evidence for nuclear factor kappa B-dependent transcriptional activation. J Clin Invest 97:421–430, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rank MA, Wollan P, Kita H, Yawn BP. Acute exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis occur in a distinct seasonal pattern. J Allergy Clin Immuonol 126:168–169, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gwaltney JM, Jr, Phillips CD, Miller RD, Riker DK. Computed tomographic study of the common cold. N Engl J Med 330:25–30, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Puhakka T, M[umlat]akel[umlat]a MJ, Alanen A, et al. Sinusitis in the common cold. J Allergy Clin Immunol 102:403–408, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kristo A, Uhari M, Luotonen J, et al. Paranasal sinus findings in children during respiratory infection evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatrics 111:e586–e589, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gwaltney JM, Jr, Hendley JO, Phillips CD, et al. Nose blowing propels nasal fluid into the paranasal sinuses. Clin Infect Dis 30:387–391, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramadan HH, Farr RW, Wetmore SJ. Adenovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in chronic sinusitis using polymerase chain reaction. Laryngoscope 107:923–925, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jang YJ, Kwon HJ, Park HW, Lee BJ. Detection of rhinovirus in turbinate epithelial cells of chronic sinusitis. Am J Rhinol 20:634–636, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang JH, Kwon HJ, Chung YS, et al. Infection rate and virus-induced cytokine secretion in experimental rhinovirus infection in mucosal organ culture: Comparison between specimens from patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and those from normal subjects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134:424–427, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gable CB, Jones JK, Lian JF, et al. Chronic sinusitis: Temporal occurrences and relationship to medical claims for upper respiratory infections and allergic rhinitis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 3:337–349, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Klemens JJ, Thompson K, Langerman A, Naclerio RM. Persistent inflammation and hyperresponsiveness following viral rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope 116:1236–1240, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. von Tiehl KF, White AA, Oldstone MB, Stevenson DD. Cytokine profiles in aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease support the theory of chronic viral infection. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 103:A21, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peters AT, Kato A, Zhang N, et al. Evidence for altered activity of the IL-6 pathway in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125:397–403, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]