Background: In the basal state, oocytes produce lactate from G6P even in the presence of oxygen.

Results: Addition of G6P to egg extracts inhibits PP1, preventing dephosphorylation/inactivation of CaMKII and initiation of apoptotic pathways.

Conclusion: Normal oocyte metabolism suppresses apoptosis by inhibiting PP1 and activating CaMKII.

Significance: These mechanistic insights suggest potential targets for modulating cell death.

Keywords: Apoptosis, CaMKII, Metabolism, Ovary, Xenopus, Caspase 2

Abstract

The metabolism of the Xenopus laevis egg provides a cell survival signal. We found previously that increased carbon flux from glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) through the pentose phosphate pathway in egg extracts maintains NADPH levels and calcium/calmodulin regulated protein kinase II (CaMKII) activity to phosphorylate caspase 2 and suppress cell death pathways. Here we show that the addition of G6P to oocyte extracts inhibits the dephosphorylation/inactivation of CaMKII bound to caspase 2 by protein phosphatase 1. Thus, G6P sustains the phosphorylation of caspase 2 by CaMKII at Ser-135, preventing the induction of caspase 2-mediated apoptotic pathways. These findings expand our understanding of oocyte biology and clarify mechanisms underlying the metabolic regulation of CaMKII and apoptosis. Furthermore, these findings suggest novel approaches to disrupt the suppressive effects of the abnormal metabolism on cell death pathways.

Introduction

Altered metabolism is well established as a contributing factor in many disease processes, including cancer, diabetes, infertility, and heart disease (1–4). However, studying the direct consequences of altered metabolic regulation in mammalian cells is cumbersome because introducing intermediate metabolites directly into the cells is not feasible. It is also difficult to do biochemistry in the limited amount of extract obtained from mammalian cell systems. Interestingly, the increased rates of glycolysis and lactic acid accumulation in neoplastically transformed cells have also been reported in newly fertilized invertebrate eggs, even under highly aerobic conditions (5). Thus, it has been suggested that studies of the more biochemically tractable Xenopus oocyte system may provide novel insights into tumor cell metabolism (1, 6). Indeed, we found that addition of G6P3 to Xenopus egg extracts leads to increased NADPH production via the pentose phosphate pathway, which enhances inhibitory phosphorylation of caspase 2 by CaMKII, promoting oocyte survival (2). Thus, the metabolic status of oocytes plays a key role in cell death regulation.

The four CaMKII isoforms (α, β, γ, and δ) form a family of multifunctional serine/threonine protein kinases that are important in many signaling cascades, from learning and memory to regulating the exit from mitosis. CaMKII plays a crucial role in cancer cell survival as well. Overexpression of CaMKII confers resistance to apoptosis induced by doxorubicin (7), and the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93 induces prostate cancer cell death (8). CaMKII exists as either a homo- or heterododecamer (9). Ca2+- and calmodulin-stimulated autophosphorylation at Thr-286/287, the canonical CaMKII activation pathway, results in formation of a constitutively active form of CaMKII that is essential for normal signaling. However, our previous study (2) found that activation of CaMKII by NADPH is independent of an increase in cytosolic Ca2+, suggesting that metabolism can regulate CaMKII via a novel non-canonical pathway.

In this study, we interrogated the mechanisms underlying metabolic regulation of CaMKII. We found that CaMKII activation was through metabolic inhibition of PP1 activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Reagents were used as described previously (2, 10). Purified calmodulin (pig brain) was purchased from EMD Millipore. Purified PP1γ (rabbit skeletal muscle) was purchased from GloboZymes. Microcystin-LR was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences and conjugated to N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated CH-Sepharose 4B as described by Moorehead et al. (11).

Recombinant Protein Cloning and Expression

N-terminally GST-tagged (pGEX-KG) Xenopus PP1 (α, β, and γ), calmodulin, CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA), and rat neurabin were expressed in, and purified from, BL21 Escherichia coli as described previously by Evans et al. (12). Xenopus caspase 2 constructs were cloned into pGEX-KG and pSP64T as described previously by Nutt et al. (2). Xenopus PP1 (α, β and γ) were amplified from Xenopus RNA by RT-PCR using the SuperScript III one-step PCR system (Invitrogen). Sequences for Xenopus PP1 isoforms were obtained from Xenbase (13). The primers used were as follows: PP1α, 5′-ATAGAATTCTAATGGGGGACGGAGAAAAACTAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATAGTCGACTTATCATTTGGACTGTTTGTTTTTGTT-3′ (reverse); PP1β, 5′-ATACTCGAGATGGCGGACGGAGAGCTGAACGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATAAAGCTTTTATCACCTCTTCTTTGGAGGATTGGCTGTC-3′ (reverse); and PP1γ, 5′-ATAGAATTCTAATGGCAGATGTTGACAAGCTAAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATAGTCGACTTATTATTTCTTTGCTTGTTTTGTGATCA-3′ (reverse). Purified PCR products were digested and cloned into pGEX-KG using EcoRI/SalI (PP1α), XhoI/HindIII (PP1β), and EcoRI/XhoI (PP1γ). Xenopus CaMKIIα was amplified from Xenopus cDNA using the following primers: CaMKIIα, 5′-TATGGATCCTACCGGTGCTAATGGACGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TATGAATTCTCAGTGTGGGAGAACAGATG-3′ (reverse). Purified PCR products were digested and cloned into pGEX-KG using BamHI/EcoRI. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) was used to create point mutations in CaMKIIα in pGEX-KG. The TT305/6AA primers were 5′-GGCCATCCTGGCTGCAATGCTGGCAACTCG-3′ and its complement. Xenopus calmodulin cDNA (pCMV-SPORT6) was purchased from Open Biosystems (catalog no. MXL1736-9507481). Calmodulin was amplified from this cDNA using the following primers: calmodulin, 5′-TATGGATCCTACCGGCTAGTTGACTGTCTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TATAAGCTTCATTTTGCAGTCATCATCTG-3′ (reverse). The purified PCR product was digested and cloned into pGEX-KG using BamHI/HindIII. Sequencing analysis confirmed the identity of all constructs. Purified mouse CaMKIIα and rat GST-neurabin were generated as described previously (14, 15). The construct to express N-terminally FLAG-tagged Xenopus caspase 2 was a gift from Dr. Sally Kornbluth (Duke University, NC).

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Recombinant Proteins

Mass spectrometry analysis of GST full-length caspase 2 (C2), GST-active C2, and GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) proteins was performed. When purified from E. coli, GST full-length C2, GST-active C2, and GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) produce two bands: one at the predicted size and one at a lower molecular weight size than expected. In each case, following mass spectrometric analysis, the lower molecular weight band was confirmed as a C-terminal truncation of the full-length recombinant protein. The expected and truncated sizes of the GST-caspase proteins were as follows: full-length GST-caspase 2, ∼74 kDa; truncated full-length GST-caspase 2, ∼56 kDa; GST-active caspase 2, ∼56 kDa; truncated GST-active caspase 2 (without the p12 fragment), ∼ 45 kDa; and GST-Pro C2, ∼44 kDa.

Peptide Synthesis and Sepharose Coupling

Calmodulin binding peptide (KRRWKKNFIAVSAANRFKKISSSGAL), corresponding to the calmodulin binding domain of myosin light chain kinase, was synthesized by the Macromolecular Synthesis Laboratory Core of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. Calmodulin binding peptide was coupled covalently to Sepharose 4B at its NH2 terminus via a hexanoic acid linker.

Caspase 3/7 Assay

At the indicated time points, 3 μl of egg extract was added to each well of a 96-well plate on ice containing 85 μl of DEVDase buffer (50 mm Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mm NaCl, 0.1% CHAPS, 10 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, and 10% glycerol). After all time points were taken, 5 μl of the caspase GLO 3/7 luminescent substrate (caspase GLO 3/7 assay, Promega) was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Luminescence values were measured using 3-s integrated readings with a SpectraMax M3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

In Vitro Translated Caspase 2 Activation

Analysis of in vitro translated caspase 2 activation was performed as described previously (2, 10).

Kinase Assays

Kinase assays were performed as described previously (2, 10). A modified in vitro kinase assay using endogenous CaMKII and GST-Pro C2 as bait and substrate was also carried out by first incubating GST-Pro C2 in egg extract for 45 min at room temperature to bind endogenous CaMKII. GST-Pro C2 (bound to CaMKII) was then retrieved, washed in egg lysis buffer (ELB) (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.7), 250 mm sucrose, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT and 50 mm KCl), and incubated in kinase buffer (25 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.5 mm DTT, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, and 50 μm ATP) with 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP with or without 500 μm CaCl2 for 45 min at room temperature. Beads were washed and analyzed for GST-Pro C2 phosphorylation as described above.

Depletions of Egg Extract/Cytosol and Recombinant Protein Binding Assays

Depletions of egg extract/cytosol and recombinant protein affinity binding assays were performed as described previously (2, 10).

CaMKII Dephosphorylation Assay

Analysis of recombinant CaMKII dephosphorylation was performed as described previously (2, 10).

Dephosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII, bound to caspase 2, was examined as follows. GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract containing 20 mm G6P for 45 min at room temperature. In the presence of G6P, GST-Pro C2 will bind phosphorylated CaMKII in egg extract (see Fig. 5C). GST-Pro C2 beads (bound to phospho-CaMKII) were washed three times in ELB and then incubated in fresh phosphatase buffer (50 μm Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol) in the absence or presence of 10 μm okadaic acid. Beads were collected at the indicated time points and washed as above. The phosphorylation status of CaMKII was determined by immunoblotting with anti-pCaMKII Thr-286/287.

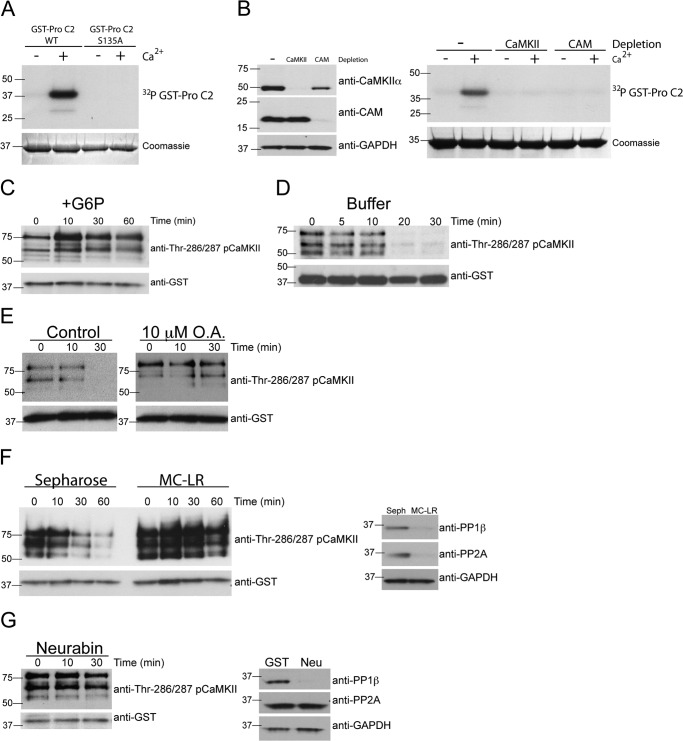

FIGURE 5.

A metabolically regulated factor inhibits PP1 dephosphorylation of CaMKII. A, CaMKII bound to caspase 2 is capable of phosphorylating caspase 2. GST-caspase 2 pro-domain (Pro C2) (WT or S135A) bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract to bind CaMKII. GST-Pro C2 bound to endogenous CaMKII was retrieved, washed, and incubated in kinase buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP in the absence or presence of 500 μm CaCl2. Beads were washed, eluted, and analyzed for GST-Pro C2 phosphorylation by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Blue staining, and autoradiography. n = > 3 independent experiments. B, CaMKII and calmodulin are required for Ca2+-induced phosphorylation of caspase 2. CaMKII or calmodulin (CAM) were depleted from egg extracts using CAM-Sepharose or calmodulin binding peptide-Sepharose, respectively. Control depletions were carried out with Sepharose alone. Left panel, selective depletion of CaMKII, and CAM was confirmed by immunoblotting for CaMKIIα, CAM, and GAPDH as a loading control. Right panel, GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in control, CaMKII-depleted, or CAM-depleted egg extracts in the absence or presence of 500 μm CaCl2 and [γ-32P]ATP. Beads were washed and analyzed as in A. n = > 3 independent experiments. C, caspase 2 binds active CaMKII in the presence of G6P. GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract in the presence of G6P. At the indicated times, beads were collected, washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for pCaMKII Thr-286/287 and GST as a loading control. n = > 3 independent experiments. D, CaMKII bound to caspase 2 is dephosphorylated rapidly when removed from egg extract. GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract containing G6P. Beads were then collected, washed, and incubated in phosphatase buffer. At the indicated times, beads were collected and analyzed for pCaMKII Thr-286/287 as in C. n = > 3 independent experiments. E, inhibition of PP1 and PP2A with okadaic acid inhibits dephosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII bound to caspase-2. Left panel, GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extracts and G6P in the presence of 10 μm okadaic acid. Beads were collected, washed, and incubated in phosphatase buffer in the absence or presence of 10 μm okadaic acid. At the indicated times, beads were collected and analyzed for pCaMKII Thr-286/287 as in C. n = 3 independent experiments. F, depletion of PP1 and PP2A inhibits dephosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII bound to caspase 2. Left panel, GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in cytosolic fractions of egg extract depleted with Sepharose or microcystin-Sepharose (MC-LR) in the presence of G6P. Beads were collected, washed, and then incubated in phosphatase buffer. At the indicated times, beads were collected and analyzed for pCaMKII Thr-286/287 as in C. Right panel, selective depletion of PP1 and PP2A was confirmed by immunoblotting for PP1β, PP2A, and GAPDH as a loading control. n = 3 independent experiments. G, depletion of PP1 inhibits dephosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII bound to caspase 2. Left panel, GST-Pro C2 bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract depleted with GST-neurabin in the presence of G6P. Beads were collected, washed, and incubated in phosphatase buffer. At the indicated times, beads were collected and analyzed for pCaMKII Thr-286/287 as in C. Right panel, selective depletion of PP1, but not PP2A, was confirmed by immunoblotting for PP1β, PP2A, and GAPDH as a loading control. n = 3 independent experiments.

Antibodies

Anti-CaMKIIα was purchased from BD Biosciences (catalog no. 611292); anti-pan CaMKII from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (catalog no. D11A10); anti-pCaMKII Thr-286/287, GAPDH, and anti-PP1γ from Abcam (catalog nos. ab32678, ab9484, and ab16387, respectively); anti-actin from Thermo Scientific (catalog no. MA1-744); anti-calmodulin and anti-PP1β from Millipore (catalog nos. 05-173 and 07-1217, respectively); anti-FLAG from Sigma (catalog no. F1804); and anti-GST and anti-PP1α from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (catalog nos. sc-138 and sc-130008, respectively).

RESULTS

Dephosphorylation of CaMKII Is Regulated Metabolically

Previous studies in Xenopus oocytes have shown that sustained levels of G6P drive the pentose phosphate pathway and NADPH production to promote oocyte survival (2). We confirmed this early finding by showing that addition of G6P to egg extracts prevented the activation of caspase 3/7, markers of the activation of apoptotic pathways (Fig. 1A). This inhibition of apoptosis is associated with sustained phosphorylation of caspase 2 at an inhibitory CaMKII site, suggesting that CaMKII activity is maintained following addition of G6P to egg extracts. We monitored CaMKII activation in egg extracts using the anti-phospho-Thr-286/287 CaMKII antibody. Fig. 1B shows that the three bands recognized by the phospho-Thr-286/287 antibody likely correspond to different CaMKII isoforms because a similar pattern of bands is detected by immunoblotting using a pan-CaMKII antibody that recognizes the α, β, γ, and δ isoforms. Note that the mobility of some bands detected using the pan-CaMKII antibody is sensitive to G6P, consistent with a change in CaMKII phosphorylation. Using the phospho-Thr-286/287-specific antibody to determine CaMKII activity in the extract revealed that the endogenous CaMKII isoforms were phosphorylated persistently at Thr-286/287 in the presence, but not the absence, of G6P (Fig. 1C) (16). Because CaMKII autophosphorylation was maintained, these data suggest that addition of G6P inhibits the phosphatase responsible for dephosphorylating Thr-286/287. To test if this was the case, we radiolabeled GST-CaMKII protein in which other autophosphorylation sites (Thr-305 and Thr-306) had been replaced with Ala, and then tested it as a substrate for protein phosphatases in egg extracts in the presence or absence of added G6P. As shown in Fig. 1D, G6P inhibits the dephosphorylation of both radiolabeled CaMKII bands (explanation of the two bands is provided under “Experimental Procedures”). Taken together, these data indicate that G6P or a metabolite regulate the oocyte phosphatase(s) that dephosphorylate Thr-286/287 in either exogenous or endogenous CaMKII.

FIGURE 1.

Activity and dephosphorylation of CaMKII is regulated metabolically. A, G6P inhibits apoptosis in egg extracts. Egg extracts were incubated in the absence or presence of G6P, and samples were taken at the indicated times and analyzed for caspase 3/7 activation using the caspase 3/7 GLO assay (Promega). n = > 3 independent experiments. B, egg extract contains multiple isoforms of CaMKII. Egg extract was treated with or without G6P, and samples were taken and immunoblotted for pan-CaMKII and pCaMKII Thr-286/287. GAPDH was used as a loading control. n = > 3 independent experiments. C, G6P maintains phosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII Thr-286/287. Egg extracts were incubated at room temperature in the absence (upper panel) or presence (lower panel) of G6P. Samples were taken at the indicated times and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα and pCaMKII Thr-286/287. n = > 3 independent experiments. D, G6P inhibits recombinant CaMKIIα Thr-286 dephosphorylation. GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract in the presence of G6P and [γ-32P]ATP. Beads were washed and then incubated in a fresh aliquot of egg extract in the absence or presence of G6P. At the indicated times, samples were taken and analyzed for GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) phosphorylation status by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Blue staining, and autoradiography. n = > 3 independent experiments.

PP1 Dephosphorylates CaMKII

Previous studies have shown that PP1, PP2A, and PP2C are capable of dephosphorylating Thr-286/287 in CaMKII in brain extracts (17). To begin to identify the metabolically regulated phosphatases responsible for CaMKII dephosphorylation in egg extracts, we depleted both PP2A and PP1 from egg extracts (lacking added G6P) using a microcystin-Sepharose affinity resin (18) (Fig. 2A), which has a similar affinity for PP1 and PP2A (19). Notably, the dephosphorylation of radiolabeled GST-CaMKII by PP1/PP2A-depleted egg extracts was diminished substantially relative to extracts depleted using control Sepharose beads (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, PP1/PP2A depletion sustained the Thr-286/287 autophosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII (Fig. 2B) and prevented the activation of caspase 3/7 (C).

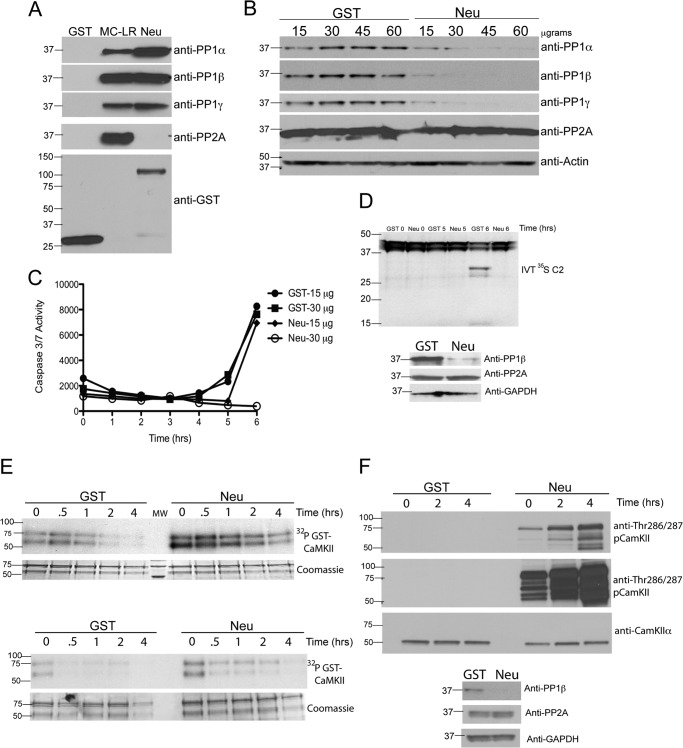

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition or depletion of PP1 inhibits CaMKII dephosphorylation and apoptosis. A, depletion of PP1 and PP2A inhibits recombinant CaMKIIα Thr-286 dephosphorylation. Upper panel, GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) was phosphorylated in egg extract in the presence of G6P as in Fig. 1A. Beads were collected, washed, and then incubated in egg extract depleted with Sepharose or microcystin-Sepharose (MC-LR). At the indicated times, samples were taken and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Blue staining, and autoradiography. Lower panel, depletion of PP1 and PP2A was confirmed by immunoblotting for PP1β, PP2A, and GAPDH as a loading control. n = > 3 independent experiments. Seph, Sepharose. B, depletion of PP1 and PP2A inhibits endogenous CaMKII Thr-286/287 dephosphorylation. Upper panel, egg extracts were depleted as in A. Samples were taken at the indicated times and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα and pCaMKII Thr-286/287. Lower panel, depletion of PP1 and PP2A was confirmed by immunoblotting for PP1β, PP2A, and GAPDH as a loading control. n = 3 independent experiments. C, depletion of PP1 and PP2A inhibits apoptosis. At the indicated times, samples were taken from egg extract depleted with Sepharose or MC-LR and analyzed for caspase 3/7 (C3/7) activation using a caspase 3/7 GLO assay (Promega). n = > 3 independent experiments. D, inhibition of PP1 and PP2A with okadaic acid inhibits recombinant CaMKIIα Thr-286 dephosphorylation. Left panel, GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) was phosphorylated in egg extract in the presence of G6P as in Fig. 1A. Beads were collected, washed, and then incubated in a fresh aliquot of egg extracts containing 1 nm or 10 μm okadaic acid. Samples were taken at the indicated times and analyzed as A. Right panel, the same experiment as displayed in the left panel, conducted independently. n = > 3 independent experiments. E, inhibition of PP1 and PP2A with okadaic acid inhibits endogenous CaMKII Thr-286/287 dephosphorylation. Egg extracts were incubated at room temperature in the presence of 10 μm okadaic acid. Samples were taken at the indicated times and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα and pCaMKII Thr-286/287. n = 2 independent experiments. F, inhibition of PP1 and PP2A with okadaic acid inhibits apoptosis. Egg extracts were incubated in the absence or presence of okadaic acid (1 nm or 10 μm), and samples were taken at the indicated times and analyzed for C3/7 activation using a caspase 3/7 GLO assay (Promega). n = 3 independent experiments.

To investigate the relative importance of PP1 and PP2A, we compared the effects of adding 1 nm or 10 μm okadaic acid (OA) to egg extracts. OA has a biphasic dose-response curve, selectively inhibiting PP2A at nanomolar concentrations but also inhibiting PP1 at micromolar concentrations (20). CaMKII was still rapidly dephosphorylated in the presence of 1 nm OA, whereas 10 μm OA substantially attenuated CaMKII dephosphorylation (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the dephosphorylation of endogenous CaMKII at Thr-286/287 and the activation of caspase 3/7 were also suppressed following PP1/PP2A inhibition by 10 μm, but not by using 1 nm OA (Fig. 2, E and F). These data are consistent with a predominant role for PP1 in the dephosphorylation of Thr-286/287 in GST-CaMKII and the initiation of apoptosis in egg extracts.

PP1 catalytic subunits are targeted to discrete subcellular compartments and regulated by interactions with proteins that typically contain a canonical PP1-binding motif with a consensus R/K-V/I-X-F sequence. To specifically deplete PP1 from egg extracts, we used a GST fusion protein containing the consensus R/K-V/I-X-F sequence and flanking sequences from neurabin, a neuronal PP1-targeting subunit (21). Although neurabin shows selectivity for mammalian PP1γ under some conditions, the selectivity between Xenopus PP1 isoforms has not been tested, and the selectivity is reduced at high concentrations (21), such as present in the egg extracts. Fig. 3A shows that neurabin binds PP1α, PP1β, and PP1γ, but not PP2A, in egg extracts, whereas microcystin-Sepharose also binds PP2A. We further show that GST-neurabin efficiently depleted all three PP1 isoforms, but not PP2A, from egg extracts in a concentration-dependent manner and that PP1 isoforms were completely depleted from the extract using more than 30 μg of GST-neurabin (Fig. 3B). Consistently, depletion of the egg extract with 30 μg, but not 15 μg, of GST-neurabin significantly delayed caspase 3 activation (Fig. 3C). Affinity depletion of PP1 isoforms from egg extracts also interfered with caspase 2 processing, as reflected by the absence of an active caspase 2 fragment (Fig. 3D). Because phosphorylation by activated/autophosphorylated CaMKII suppresses caspase 2 activation, we predicted that PP1 depletion would also maintain CaMKII phosphorylation. The selective depletion of PP1 from egg extracts using GST-neurabin also inhibited the dephosphorylation of exogenous 32P-labeled GST-CaMKII in the absence of G6P (Fig. 3E) and the dephosphorylation of Thr-286/287 in endogenous CaMKII (F), suggesting that ongoing inhibition of PP1 is necessary for sustained CaMKII activation in egg extracts. Together, these data demonstrate that PP1 is the major phosphatase involved in both dephosphorylating CaMKII and in initiating apoptotic pathways in Xenopus egg extracts.

FIGURE 3.

Depletion of PP1 inhibits apoptosis and dephosphorylation of CaMKII. A, recombinant neurabin binds all isoforms of PP1 but not PP2A. GST or GST-neurabin (Neu) bound to glutathione-Sepharose or microcystin conjugated to Sepharose (MC-LR) was incubated in egg extract. The beads were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ, PP2A, and GST as a loading control. n = > 3 independent experiments. B, depletion of PP1 inhibits caspase 3/7 activation. Egg extracts were depleted of PP1 with indicated concentrations of GST-neurabin. Immunoblotting confirmed the selective depletion of PP1 isoforms, but not PP2A, by GST-neurabin. Actin was used as a loading control. C, samples were taken from egg extracts depleted with GST or GST-neurabin at the indicated times and analyzed for caspase 3/7 activation using a caspase 3/7 Glo assay (Promega). n = 2 independent experiments. D, depletion of PP1 inhibits caspase 2 processing. Eggs extracts were depleted using GST or GST-neurabin bound to glutathione-Sepharose. Upper panel, egg extract depleted with GST or GST-neurabin was incubated with in vitro-translated (IVT) 35S-labeled full-length caspase 2 (C2). Samples were taken at the indicated times and analyzed for C2 processing by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Processing of caspase 2 is indicated by cleavage of full-length caspase 2 (∼45 kDa) to lower molecular weight cleavage products (∼30 kDa and ∼15 kDa). Note the 6-h time point in GST 6 versus Neu 6 (lanes 5 and 6). Lower panel, selective depletion of PP1, but not PP2A, was confirmed by immunoblotting for PP1β, PP2A, and GAPDH as a loading control. n = 3 independent experiments. E, depletion of PP1 inhibits recombinant CaMKIIα Thr-286 dephosphorylation. Upper panel, GST-CaMKIIα (TT305/6AA) bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP as in Fig. 1A. Beads were collected, washed, and then incubated in egg extract depleted with GST or GST-neurabin. At the indicated times, samples were taken and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Blue staining, and autoradiography. Lower panel, the same experiment as displayed in the upper panel, conducted independently. n = > 3 independent experiments. F, depletion of PP1 inhibits endogenous CaMKII Thr-286/287 dephosphorylation. Upper panel, egg extracts were depleted of PP1 using GST-neurabin as in Fig. 2B. Samples were taken at the indicated times and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα and pCaMKII Thr-286/287. Long and short exposures of pCaMKII (Thr-286/287) are shown. Lower panel, selective depletion of PP1, but not PP2A, was confirmed by immunoblotting for PP1β, PP2A, and GAPDH as a loading control. n = 2 independent experiments.

Caspase 2 Acts as a Scaffold to Bind CaMKII, Calmodulin, and PP1

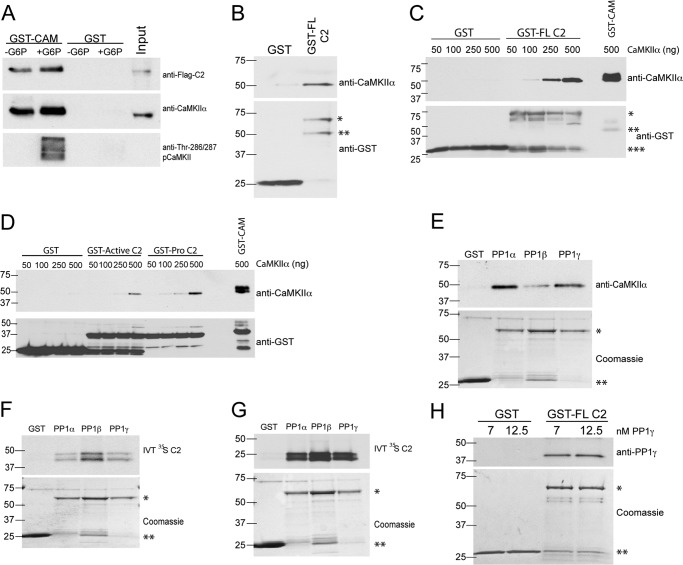

We have shown previously that PP1 binds to Xenopus caspase 2 in egg extracts (10). Because CaMKII associates with many of its substrates, we investigated whether CaMKII is also associated with caspase 2-PP1 complexes to regulate CaMKII phosphorylation. Egg extracts were spiked with in vitro-translated FLAG-tagged Xenopus caspase 2 and then incubated with a calmodulin-Sepharose affinity resin in the presence or absence of G6P. The calmodulin-Sepharose bound comparably to non-phosphorylated CaMKII in the absence of G6P or to Thr-286/287 autophosphorylated CaMKII in the presence of G6P, as predicted (Fig. 4A). Notably, the FLAG-caspase 2 also bound to calmodulin-Sepharose in the presence or absence of G6P. To better understand the interaction of CaMKII with caspase 2, egg extracts were incubated with GST-caspase 2 (full-length), and complexes isolated using glutathione-Sepharose were probed for endogenous CaMKIIα. Fig. 4B shows that the endogenous CaMKIIα binds to GST-caspase 2.

FIGURE 4.

Caspase 2 acts as scaffold for, and binds directly to, PP1 and CaMKII. A, FLAG-tagged caspase 2 and CaMKII coprecipitate with recombinant calmodulin. GST or GST-calmodulin (CAM) bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract containing in vitro-translated FLAG-caspase 2 (C2) full-length in the absence or presence of G6P. Beads were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for FLAG, CaMKIIα, and pCaMKII Thr-286/287. n = 3 independent experiments. B, CaMKII coprecipitates with full-length caspase 2. GST or GST-C2 (full-length) conjugated to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract. Beads were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα and GST as a loading control. *, GST-full-length C2; **, GST-full-length C2 (C-terminal truncation, see “Experimental Procedures”). n = > 3 independent experiments. C, CaMKIIα binds directly to recombinant full-length caspase-2. GST, GST-C2 (full-length) or GST-CAM bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in kinase buffer with the indicated concentrations of recombinant CaMKIIα. Beads were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα and GST as a loading control. *, GST-full-length C2 (fifth through eighth lanes); **, GST-CAM (tenth lane); ***, GST. n = 3 independent experiments. D, CaMKIIα binds directly to recombinant caspase 2 pro-domain. GST, GST-active C2 (containing the catalytic domain of caspase 2), GST-Pro C2, or GST-CAM was incubated in kinase buffer with indicated concentrations of recombinant CaMKIIα and analyzed as in F. n = 3 independent experiments. E, CaMKII coprecipitates with recombinant PP1. GST or GST-PP1 (α, β, or γ) bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in egg extract. Beads were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for CaMKIIα. GST-PP1 (α, β, or γ) was detected by Coomassie staining and used as a loading control. *, GST-PP1; **, GST. n = > 3 independent experiments. F, in vitro-translated (IVT) caspase 2 coprecipitates with recombinant PP1. GST or GST-PP1 (α, β, or γ) bound to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in cytosolic fractions of egg extract containing in vitro-translated 35S-labeled, full-length C2. Beads were washed, eluted, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. GST and GST-PP1 (α, β, or γ) were detected by Coomassie staining and used as a loading control. *, GST-PP1; **, GST. n = 3 independent experiments. G, in vitro-translated caspase 2 binds directly to recombinant PP1. GST or GST- PP1 (α, β, or γ) conjugated to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in kinase buffer containing in vitro-translated 35S-labeled, full-length C2. Beads were washed, eluted, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. GST and GST-PP1 (α, β, or γ) were detected by Coomassie staining and used as loading control. *, GST-PP1; **, GST. n = 2 independent experiments. H, PP1γ binds directly to full-length caspase 2. GST or GST-C2 (full-length) conjugated to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated in kinase buffer containing the indicated concentrations of purified PP1γ. Beads were washed, eluted, and immunoblotted for PP1γ. GST and GST-C2 (full-length) were detected by Coomassie staining and used as a loading control. *, GST-C2 (full-length); **, GST. n = 2 independent experiments.

To determine whether CaMKII directly interacts with caspase 2, we incubated Xenopus GST-caspase 2 (full-length) with various concentrations of purified mammalian CaMKIIα. Fig. 4C shows that CaMKII directly binds to caspase 2. Furthermore, we found that purified CaMKII directly interacted with GST fusion proteins containing either the pro-domain of caspase 2 (GST-Pro C2) or the catalytic active domain of caspase 2 (GST-ActiveC2) (Fig. 4D). However, binding at lower concentrations of CaMKII was detected using GST-Pro C2 but not when using GST-active C2. Furthermore, although calmodulin does not directly bind to caspase 2 (data not shown), calmodulin appears to be associated indirectly with the caspase 2 complex (Fig. 4A), perhaps via an interaction with CaMKII.

We have shown previously that PP1 binds constitutively to caspase 2 in the egg extracts. To examine whether caspase 2 preferentially binds to PP1 isoforms, we spiked egg extracts with in vitro-translated caspase 2 and then added recombinant PP1α, PP1β, or PP1γ (fused to GST). Protein complexes were isolated using glutathione-Sepharose. Both endogenous CaMKIIα and the in vitro-translated caspase 2 bound all three isoforms of PP1 (Fig. 4, E and F). Furthermore, the in vitro-translated 35S-labeled caspase 2 associated with all three PP1 catalytic isoforms in the absence of the egg extract (Fig. 4G). Moreover, untagged purified mammalian PP1γ associated directly with GST-caspase 2 (full-length protein) (Fig. 4H). Note that the GST-caspase 2 migrates as two bands: one of the predicted size and a second smaller band (see “Experimental Procedures”). These results establish that all three PP1 isoforms interact directly with caspase 2 (10). Taken together, the data in Fig. 4 suggest that both CaMKII and PP1 bind to caspase 2.

A G6P-induced Factor Inhibits PP1-mediated Dephosphorylation of CaMKII Thr-286/287

To investigate the metabolic regulation of PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of CaMKII, we developed an in vitro dephosphorylation assay using recombinant caspase 2 as bait to bind endogenous CaMKII and endogenous PP1. To first determine whether bound CaMKII could phosphorylate caspase 2, the protein complexes bound to GST-Pro C2 (WT or S315A) retrieved from egg extracts using glutathione-Sepharose were washed with an isotonic buffer and then mixed with a kinase buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP (see “Experimental Procedures”). The WT but not S135A Pro C2 was efficiently phosphorylated in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). The WT and S135A GST-Pro C2 proteins bound similar amounts of endogenous CaMKII (data not shown), demonstrating that the lack of phosphorylation does not result from a lack of CaMKII binding to the mutant GST-Pro C2 domain. Furthermore, depletion of either CaMKII or calmodulin from the extracts prevented the phosphorylation of the WT GST-Pro C2 protein incubated in egg extract in the presence of Ca2+ (Fig. 5B).

Egg extracts were then incubated at room temperature with GST-Pro C2 in the presence of G6P, and complexes were isolated at various times using glutathione-Sepharose. As expected, Thr-286/287-autophosphorylated CaMKII was detected in the complex, and sustained incubation of the complex in the G6P-enriched extract did not result in substantial dephosphorylation of the isolated CaMKII (Fig. 5C). However, incubation of this isolated complex in buffer at room temperature resulted in the time-dependent dephosphorylation of the CaMKII (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data suggest that G6P, or a downstream metabolite, inhibits the phosphatase. Notably, the dephosphorylation of CaMKII bound to GST-Pro C2 was inhibited by 10 μm okadaic acid (Fig. 5E), suggesting the involvement of PP1 and/or PP2A. To provide further insight into the identity of phosphatases responsible for CaMKII dephosphorylation in this complex, GST-Pro C2 complexes were isolated from G6P-treated egg extracts that had been depleted of both PP1 and PP2A using microcystin-Sepharose or of PP1 alone using GST-neurabin. Notably, Thr-286/287-phosphorylated CaMKII was readily detected bound to GST-Pro C2, but the time-dependent dephosphorylation in the isolated complex was essentially abrogated completely by depletion of PP1 and PP2A (Fig. 5F) or PP1 alone (G). Together, these data show that G6P, or a downstream metabolite, can inhibit the PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of CaMKII at Thr-286/287 in complexes associated with GST-Pro C2.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that apoptosis is regulated by the phosphorylation of several proteins by multiple protein kinases. However, the counter-regulatory roles of protein phosphatases in regulating cell survival are less well understood. Previous studies have found that PP2A or PP1 can directly activate proapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins by dephosphorylation in an endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent or glucose deprivation-dependent cell death, respectively (23, 24). In addition, the net activity of the proapoptotic protein Bad depends on the balance between suppression because of PKA phosphorylation and activation by PP1 dephosphorylation in a complex coordinated by the A kinase-anchoring protein Wiskott-Aldrich family member WAVE-1 (23, 25). Here we provide evidence that PP1 regulation of CaMKII and caspase 2 is important in modulating caspase activation in response to the addition of G6P.

We interpret our data to indicate that G6P, or the sustained production of a soluble metabolic signal(s), blocks PP1 from dephosphorylating CaMKII in the complex with caspase 2. In extracts lacking a G6P supplement, the absence of this metabolic signal allows a default cell death pathway to be initiated by PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of CaMKII in the caspase 2 complex. This finding is consistent with the original hypothesis of Martin Raff, published in 1992, stating that, “cells constitutively express all of the proteins required to undergo programmed cell death (PCD) and undergo PCD unless continuously signaled not to” (26). However, direct addition of G6P or NADPH (a major product of the pentose phosphate pathway) to the isolated complex failed to protect CaMKII from dephosphorylation (data not shown). Thus, it will be important for future studies to identify the molecule(s) that provide this metabolic signal.

The molecular basis for the assembly of this complex remains to be elucidated. PP1 specificity is typically conferred by a targeting subunit that directs the catalytic subunit to its substrates by altering its subcellular localization, modifying the substrate selectivity and/or modulating the activity (27). PP1 activity and specificity may also be modulated by additional posttranslational modifications (28). When deciphering the activation of caspase 2 by dephosphorylation of Ser-135, we were able to show that the PP1 catalytic subunit binds constitutively to caspase 2 and was responsible for dephosphorylation and activation of caspase 2 (10). Although we showed that PP1 binds to caspase 2 directly, caspase 2 seems to lack a clearly identified canonical PP1-binding motif. Thus, further studies will be required to understand the basis for this interaction.

Similarly, the biological roles of CaMKII are also influenced by its interactions with other proteins. Work in the CNS has shown that CaMKII can interact with other proteins by diverse mechanisms (29, 30). Our data show that CaMKII also interacts with the caspase 2-PP1 complex. Within this complex, CaMKII can phosphorylate the critical modulatory site Ser-135 in caspase 2 and also serves as a substrate for the bound PP1. Interestingly, studies in the brain indicate that the availability of CaMKII to protein phosphatases is modulated by subcellular targeting. Soluble CaMKII is dephosphorylated preferentially by PP2A, whereas CaMKII associated with the postsynaptic density is a preferential substrate for PP1 (31). Moreover, PP1 has a gatekeeping role in modulating synaptic CaMKII activation (32), and more recent studies have shown that CaMKII and PP1 coassemble with the synaptic scaffolding protein spinophilin (21, 22, 33). Our demonstration of a complex with caspase 2 provides a novel mechanism for targeting PP1 to regulate CaMKII that appears to play an important role in the recruitment of apoptotic pathways in oocytes.

Interestingly, the activity of PP1 toward CaMKII in the complex with caspase 2 appears to be suppressed by the metabolic signal that might be generated following the addition of G6P to the egg extracts. This provides a non-canonical mechanism for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII that suppresses apoptosis in oocytes. It is interesting to note that the metabolism of oocytes resembles the abnormal metabolism of tumor cells, which are also resistant to cell death. Thus, developing a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying these links might suggest novel strategies for therapeutic intervention directed at blocking this metabolic “brake” on apoptosis via PP1 and CaMKII to promote the death of transformed cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jan Bouten, Maren Cam, Matthew Parker, and Adam Gromley for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health Award Number P30CA021765. This work was also supported by the V Foundation and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

- G6P

- glucose-6-phosphate

- CaMKII

- calcium/calmodulin regulated protein kinase II

- PP1

- protein phosphatase 1

- OA

- okadaic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nutt L. K. (2012) The Xenopus oocyte. A model for studying the metabolic regulation of cancer cell death. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 412–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nutt L. K., Margolis S. S., Jensen M., Herman C. E., Dunphy W. G., Rathmell J. C., Kornbluth S. (2005) Metabolic regulation of oocyte cell death through the CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of caspase-2. Cell 123, 89–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shah S. H., Kraus W. E., Newgard C. B. (2012) Metabolomic profiling for the identification of novel biomarkers and mechanisms related to common cardiovascular diseases. Form and function. Circulation 126, 1110–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newgard C. B., Attie A. D. (2010) Getting biological about the genetics of diabetes. Nat. Med. 16, 388–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warburg O. (1956) On the origin of cancer cells. Science 123, 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dworkin M. B., Dworkin-Rastl E. (1989) Metabolic regulation during early frog development. Glycogenic flux in Xenopus oocytes, eggs, and embryos. Dev. Biol. 132, 512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rokhlin O. W., Taghiyev A. F., Bayer K. U., Bumcrot D., Koteliansk V. E., Glover R. A., Cohen M. B. (2007) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II plays an important role in prostate cancer cell survival. Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 732–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rokhlin O. W., Guseva N. V., Taghiyev A. F., Glover R. A., Cohen M. B. (2010) KN-93 inhibits androgen receptor activity and induces cell death irrespective of p53 and Akt status in prostate cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 9, 224–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hudmon A., Schulman H. (2002) Structure-function of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 364, 593–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nutt L. K., Buchakjian M. R., Gan E., Darbandi R., Yoon S. Y., Wu J. Q., Miyamoto Y. J., Gibbon J. A., Andersen J. L., Freel C. D., Tang W., He C., Kurokawa M., Wang Y., Margolis S. S., Fissore R. A., Kornbluth S. (2009) Metabolic control of oocyte apoptosis mediated by 14-3-3ζ-regulated dephosphorylation of caspase-2. Dev. Cell 16, 856–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moorhead G., MacKintosh R. W., Morrice N., Gallagher T., MacKintosh C. (1994) Purification of type 1 protein (serine/threonine) phosphatases by microcystin-Sepharose affinity chromatography. FEBS Lett. 356, 46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evans E. K., Kornbluth S. (1998) Regulation of apoptosis in Xenopus egg extracts. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 38, 265–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bowes J. B., Snyder K. A., Segerdell E., Jarabek C. J., Azam K., Zorn A. M., Vize P. D. (2010) Xenbase. Gene expression and improved integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D607–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robison A. J., Bass M. A., Jiao Y., MacMillan L. B., Carmody L. C., Bartlett R. K., Colbran R. J. (2005) Multivalent interactions of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II with the postsynaptic density proteins NR2B, densin-180, and α-actinin-2. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35329–35336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brickey D. A., Colbran R. J., Fong Y. L., Soderling T. R. (1990) Expression and characterization of the α-subunit of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II using the baculovirus expression system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 173, 578–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pi H. J., Otmakhov N., Lemelin D., De Koninck P., Lisman J. (2010) Autonomous CaMKII can promote either long-term potentiation or long-term depression, depending on the state of T305/T306 phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 30, 8704–8709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Colbran R. J. (2004) Protein phosphatases and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 24, 8404–8409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ichinose M., Endo S., Critz S. D., Shenolikar S., Byrne J. H. (1990) Microcystin-LR, a potent protein phosphatase inhibitor, prolongs the serotonin- and cAMP-induced currents in sensory neurons of Aplysia californica. Brain Res. 533, 137–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weiser D. C., Shenolikar S. (2003) Use of protein phosphatase inhibitors. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 13:Unit 13.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Margolis S. S., Walsh S., Weiser D. C., Yoshida M., Shenolikar S., Kornbluth S. (2003) PP1 control of M phase entry exerted through 14-3-3-regulated Cdc25 dephosphorylation. EMBO J. 22, 5734–5745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carmody L. C., Baucum A. J., 2nd, Bass M. A., Colbran R. J. (2008) Selective targeting of the γ1 isoform of protein phosphatase 1 to F-actin in intact cells requires multiple domains in spinophilin and neurabin. FASEB J. 22, 1660–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baucum A. J., 2nd, Brown A. M., Colbran R. J. (2012) Differential association of postsynaptic signaling protein complexes in striatum and hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 124, 490–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Danial N. N., Gramm C. F., Scorrano L., Zhang C. Y., Krauss S., Ranger A. M., Datta S. R., Greenberg M. E., Licklider L. J., Lowell B. B., Gygi S. P., Korsmeyer S. J. (2003) BAD and glucokinase reside in a mitochondrial complex that integrates glycolysis and apoptosis. Nature 424, 952–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Puthalakath H., O'Reilly L. A., Gunn P., Lee L., Kelly P. N., Huntington N. D., Hughes P. D., Michalak E. M., McKimm-Breschkin J., Motoyama N., Gotoh T., Akira S., Bouillet P., Strasser A. (2007) ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell 129, 1337–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danial N. N., Korsmeyer S. J. (2004) Cell death. Critical control points. Cell 116, 205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raff M. C. (1992) Social controls on cell survival and cell death. Nature 356, 397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bollen M., Peti W., Ragusa M. J., Beullens M. (2010) The extended PP1 toolkit. Designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 450–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Margolis S. S., Perry J. A., Weitzel D. H., Freel C. D., Yoshida M., Haystead T. A., Kornbluth S. (2006) A role for PP1 in the Cdc2/Cyclin B-mediated positive feedback activation of Cdc25. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 1779–1789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Colbran R. J. (2004) Targeting of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem. J. 378, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jalan-Sakrikar N., Bartlett R. K., Baucum A. J., 2nd, Colbran R. J. (2012) Substrate-selective and calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by α-actinin. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15275–15283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Strack S., Barban M. A., Wadzinski B. E., Colbran R. J. (1997) Differential inactivation of postsynaptic density-associated and soluble Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by protein phosphatases 1 and 2A. J. Neurochem. 68, 2119–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blitzer R. D., Connor J. H., Brown G. P., Wong T., Shenolikar S., Iyengar R., Landau E. M. (1998) Gating of CaMKII by cAMP-regulated protein phosphatase activity during LTP. Science 280, 1940–1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baucum A. J., 2nd, Strack S., Colbran R. J. (2012) Age-dependent targeting of protein phosphatase 1 to Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II by spinophilin in mouse striatum. PloS ONE 7, e31554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]