Background: Both secreted HSP90α and overexpressed TCF12 enhance colorectal cancer (CRC) cell migration/invasion.

Results: Secreted HSP90α induces the CD91/IκB kinase/NF-κB/TCF12 cascade to down-regulate E-cadherin and to enhance CRC cell migration/invasion.

Conclusion: Secreted HSP90α acts through TCF12 expression to enhance CRC cell spreading.

Significance: Secreted HSP90α contributes to tumor TCF12 overexpression and can be a therapeutic target of CRC.

Keywords: Cell Invasion, Cell Migration, E-cadherin, EMT, HSP90, TCF12

Abstract

Secreted levels of HSP90α and overexpression of TCF12 have been associated with the enhancement of colorectal cancer (CRC) cell migration and invasion. In this study, we observed that CRC patients with tumor TCF12 overexpression exhibited both a higher rate of metastatic occurrence and a higher average serum HSP90α level compared with patients without TCF12 overexpression. Therefore, we studied the relationship between the actions of secreted HSP90α and TCF12. Like overexpressed TCF12, secreted HSP90α or recombinant HSP90α (rHSP90α) induced fibronectin expression and repressed E-cadherin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and gap junction levels in CRC cells. Consistently, rHSP90α stimulated invasive outgrowths of CRC cells from spherical structures during three-dimensional culture. rHSP90α also induced TCF12 expression in CRC cells. Its effects on CRC cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration, and invasion were drastically prevented when TCF12 was knocked down. This suggests that TCF12 expression is required for secreted HSP90α to enhance CRC cell spreading. Through the cellular receptor CD91, rHSP90α facilitated the complex formation of CD91 with IκB kinases (IKKs) α and β and increased the levels of phosphorylated (active) IKKα/β and NF-κB. Use of an IKKα/β inhibitor or ectopic overexpression of dominant-negative IκBα efficiently repressed rHSP90α-induced TCF12 expression. Moreover, κB motifs were recognized in the gene sequence of the TCF12 promoter, and a physical association between NF-κB and the TCF12 promoter was detected in rHSP90α-treated CRC cells. Together, these results suggest that the CD91/IKK/NF-κB signaling cascade is involved in secreted HSP90α-induced TCF12 expression, leading to E-cadherin down-regulation and enhanced CRC cell migration/invasion.

Introduction

The heat shock protein HSP90α is a well known chaperone molecule responsible for the proper folding, maturation, and intracellular trafficking of numerous cancer-related proteins, including ErbB2/Neu, Bcr-Abl, Raf-1, Akt, HIF-1α, and mutated p53 (1, 2). It is expressed and localized in the cytoplasm and on the cell surface (3–5) and is also secreted by many types of cancer cells (6–8). In our previous study, cellular secretion of HSP90α from colorectal cancer (CRC)3 cells was enhanced after serum starvation, and secreted HSP90α could be used to stimulate migration and invasion of other non-serum-starved cells (8). CD91 is a cell membrane receptor for secreted HSP90 (9). Upon binding with HSP90α, CD91 elicits a NF-κB-dependent pathway for the induction of integrin αV expression and further promotes migration and invasion of CRC cells (8). CD91 can also interact with the coreceptor EphA2 for secreted HSP90α to facilitate lamellipodial formation and subsequent motility and invasion of glioblastoma multiforme cells (10).

TCF12 is a class I member of the helix-loop-helix protein family, and tumor TCF12 overexpression was preferentially detected in CRC patients with cancer metastasis (11). Upon knockdown or ectopic overexpression in CRC cell lines, TCF12 was associated with cellular epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by inducing fibronectin expression and repressing E-cadherin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and gap junction levels. Furthermore, it facilitated CRC cell migration, invasion, and metastasis (11). TCF12 was shown to be physically associated with the promoter region of the E-cadherin gene and coexpressed and co-immunoprecipitated with Bmi1 and EZH2, suggesting that TCF12 transcriptionally represses E-cadherin expression via polycomb group-repressive complexes PRC1 and PRC2 (11). The clinical correlation of tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression with tumor E-cadherin mRNA down-regulation confirmed that TCF12 could be an important transcriptional repressor responsible for E-cadherin down-regulation in CRC. However, the factors inducing TCF12 overexpression in CRC cells remain to be elucidated. We hypothesized that secreted HSP90α may act through TCF12 expression to regulate CRC cell migration and invasion.

In this study, we observed that CRC patients with tumor TCF12 overexpression exhibited a significantly higher rate of metastatic occurrence and a higher average serum HSP90α level compared with patients without TCF12 overexpression. Like TCF12 overexpression, cellular secreted HSP90α and recombinant HSP90α (rHSP90α) induced fibronectin expression but repressed E-cadherin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and gap junction levels in CRC cells. Additionally, rHSP90α induced TCF12 expression, and its effects on cellular expression of E-cadherin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and fibronectin and cellular levels of gap junction, migration, and invasion were significantly diminished in TCF12-knockdown cells, suggesting that TCF12 is required for the functions of secreted HSP90α. CD91 is a cell membrane receptor for extracellular HSP90α. Our results reveal that a CD91/IκB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB signaling cascade is involved in secreted HSP90α-induced TCF12 expression, which in turn results in E-cadherin down-regulation and enhanced CRC cell migration/invasion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Clinical Specimens

Tissue and serum specimens were collected from 60 CRC patients who underwent surgical resections of tumors at Taipei Veterans General Hospital during 1993–2004. Sera were collected before surgery. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient in accordance with the medical ethics protocol approved by the Human Clinical Trial Committee of the hospital. For comparison, non-tumor tissues were taken from the specimen sites >10 cm away from tumors and were pathologically certified to be free of tumor cells. Patients with tumors that could not be completely removed and patients who had received chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy before surgery were excluded from this study.

Cell Culture

Human CRC cell lines HCT-115, SW480, and SW620 were cultivated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 mm l-glutamine. LoVo cells were maintained under the same conditions, except that Ham's F-12 medium with 20% FBS was used instead. All of the cell lines were authenticated by examining 15 short tandem repeat loci (CSF1PO, D2S1338, D3S1358, D5S818, D7S820, D8S1179, D13S317, D16S539, D18S51, D19S433, D21S11, FGA, TH01, TPOX, and vWA) and the gender marker amelogenin using the AmpF/STR® Identifiler® PCR amplification kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the ATCC fingerprint database. The last authentication was performed in July 2012. Establishment of stable TCF12-knockdown SW620 and LoVo cell clones was done and described in our previous study (11). Representative clones derived from two of four different shRNA sequences targeting TCF12 mRNA were used for analyses in this study. For inhibition of NF-κB signaling, HCT-115 and SW480 cells were transfected with pRc/CMV-IκB72 plasmids (kindly provided by Dr. Shuang-En Chuang) to overexpress dominant-negative IκBα (dnIκBα) that lacked amino acids 2∼71 of wild-type IκBα, a region required for IKK-induced phosphorylation and degradation but dispensable for binding to NF-κB.

Collection of Serum Starvation Conditioned Medium

HCT-115 and SW480 cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells in a 10-cm dish and incubated overnight. Cells were then washed with PBS and incubated with 10 ml of fresh RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.5% FBS for serum starvation. After 72 h, the conditioned medium (CM) was collected, centrifuged, and filtered through 0.45-μm filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Assay of Secreted HSP90α Levels

Aliquots of 20-fold diluted serum samples were loaded into 96-well plates (100 μl/well) for determining HSP90α levels (8). Each well was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 1 μg/ml anti-HSP90α antibody (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC). After the washes, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was added and incubated for another 1 h. Finally, the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (0.3 mg/ml; Sigma) in 0.015% H2O2 was added and incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. The reactions were stopped using 0.5 m H2SO4, and product levels were detected by measuring absorbance values at 450 nm using an Infinite M200 microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Different amounts of rHSP90α (Stressgen Inc., Ann Arbor, MI) diluted in 1 mg/ml BSA were used as standards. The levels of HSP90α in cell culture media were detected in the same way, except that rHSP90α standards were prepared in 0.05 mg/ml BSA.

RT-PCR

Total RNA from cultured cells or tissues was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland). The resultant cDNA was used as the template for real-time PCR in the Rotor-Gene 3000 system (Corbett Research, Mortlake, Australia) using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Cambrex Corp., East Rutherford, NJ). The primers and PCR conditions have been described previously (8, 11). The levels of GAPDH were also detected as internal controls for normalization. The data were analyzed using Rotor-Gene v5.0 software (Corbett Research).

Assay of Gap Junction Activity

Cellular gap junction activity was evaluated by assaying the calcein transfer between cells (11). Adherent cells were trypsinized and stained using Calcein acetoxymethyl ester and 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) (Invitrogen) as dye donor cells and then added to a monolayer of unstained (dye recipient) cells of the same type at a ratio of 1:10 (donor/recipient). After co-culturing for 0.2 or 3 h, the monolayer of cells were trypsinized, resuspended in PBS, and immediately analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Three-dimensional Culture

The wells of a 24-well dish were precoated with Matrigel (250 μl for each; BD Biosciences) and seeded with 1 × 104 CRC cells in the culture medium plus 2% Matrigel. Fresh Matrigel-supplemented medium was added every 2 days until the formation of cellular spherical structures was observed. These cells were then treated for 72 h with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α in the culture medium plus 2% Matrigel. The change in morphology was observed using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope.

Cell Migration and Invasion Assays

For the cell migration assay, the monolayer of CRC cells was wound with a white tip, washed twice with PBS, and incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. Pictures of the cells migrating into the wounded area were taken every 10 min using a CCM-330F system (Astec Co., Fukuoka, Japan) and analyzed with Image-Pro Plus version 5.0.2 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Silver Spring, MD). For the invasion assay, the cells were suspended in 0.5% FBS-containing culture medium and loaded into the top chambers of Transwell inserts precoated with 5-fold diluted Matrigel. Cells were allowed to migrate for 16 h through the Matrigel toward the bottom chambers containing culture medium plus 10% FBS. The filters of the Transwell inserts were then fixed and stained with Giemsa, and pictures were taken of the invasive cells on the filters, followed by quantification using Image-Pro Plus software.

Immunoblot Analysis

Total cell lysate was prepared in lysis buffer consisting of 10 mm Na2HPO4, 1.8 mm KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.3% SDS, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (12). Nuclear extract was prepared using the reagents and protocol provided in the NE-PERTM nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents kit (Pierce). Immunoblot analyses were performed according to the canonical procedure (12). We used antibodies against NF-κB p65, IKKα, and phosphorylated IKKα/β (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA); phosphorylated NF-κB p65 and phosphorylated Akt (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); connexin-43 (Sigma); integrin αV (BD Biosciences); matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Lab Vision/NeoMarkers Co., Fremont, CA); and IKKβ, TCF12, E-cadherin, connexin-26, fibronectin, GAPDH, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, Akt, ERK, phosphorylated ERK, JNK, phosphorylated JNK, p38, and phosphorylated p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

ChIP was performed using the EZ-ChIP kit (Millipore). The PBS- or rHSP90α-treated cells were incubated with 1% formaldehyde before cell lysis and DNA fragmentation. After preclearing by protein G-conjugated agarose, 10-μl aliquots of lysates were saved as “input” fractions, and the remaining lysates were immunoprecipitated with control IgG or anti-NF-κB antibody. DNA was extracted for PCR amplification of the κB site-containing region (−783 to −560) of the TCF12 gene using primers 5′-GGG-CTG-TCT-CCG-TTA-GAT-GA-3′ and 5′-CGG-TCA-GAT-TCG-ATG-CAG-AG-3′. PCR was performed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 30 s. An additional PCR experiment using primers against the regions upstream and downstream of the κB site-containing region was also performed to monitor specificity of the assay.

Proximity Ligation Assay

CRC cells seeded on glass coverslips (2 × 105 cells/22 × 22-mm coverslip) were treated with PBS or rHSP90α for 24 h. After fixing with 3% paraformaldehyde and blocking with the blocking solution supplied in the Duolink in situ PLA kit (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden), the cells were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with 4 μg/ml anti-IKKα or IKKβ antibody and washed with Tris-buffered saline plus 0.05% Tween 20, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with antibody against CD91α (6.25 μg/ml; BD Biosciences), IKKα (2.5 μg/ml), or IKKβ (2.5 μg/ml). The remaining procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions for the Duolink in situ PLA kit. The final images were taken and analyzed using a TSC SP5 confocal microscope and LASAF software (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Statistical Analyses

Results of the cell culture studies were analyzed using Student's t test. Comparison of the serum HSP90α levels between the two patient groups was performed by the independent samples t test. Pearson χ-square analysis was performed to correlate tumor TCF12 overexpression with the metastatic occurrence. Differences were considered significant if p values were <0.05 (two-tailed tests).

RESULTS

Patients with Tumor TCF12 mRNA Overexpression Exhibit Higher Serum HSP90α Levels

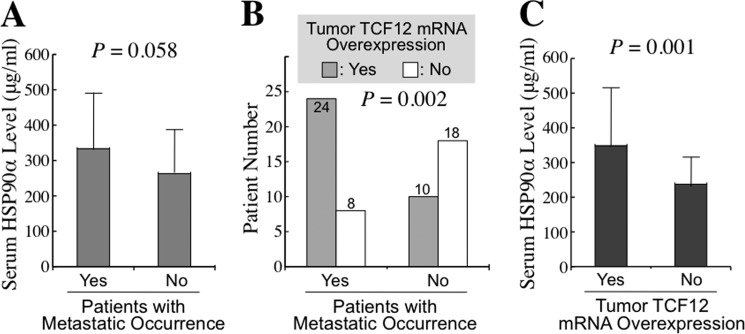

We measured the secreted HSP90α levels in serum samples of 60 CRC patients, including 32 patients with metastasis and 28 without metastasis. In parallel with the result we reported previously, a higher average serum HSP90α level was detected in patients with metastasis compared with those without metastasis, although the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (333.2 ± 157.0 versus 263.0 ± 124.3 μg/ml, p = 0.058) (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, the patient group with metastasis had significantly more cases of tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression than did the patient group without metastasis (24/32 versus 10/28, p = 0.002) (Fig. 1B). This result was also consistent with our previous study. The relationship between serum HSP90α levels and tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression was investigated as a follow-up. The average serum HSP90α level was 348.5 ± 167.1 μg/ml in the patient group with tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression, which was significantly higher than the level of 237.5 ± 78.2 μg/ml in the patients without TCF12 mRNA overexpression in their tumor tissues (p = 0.001) (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Elevated serum HSP90α levels and tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression in CRC patients. The serum levels of HSP90α and the tumor status of TCF12 mRNA expression were investigated in 60 CRC patients, including 32 cases with metastasis and 28 cases without metastasis. A, a higher average serum HSP90α level was detected in patients with metastasis compared with patients without metastasis (333.2 ± 157.0 versus 263.0 ± 124.3 μg/ml, p = 0.058). B, tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression was detected in a higher proportion of patients with metastasis than without metastasis (24/32 versus 10/28, p = 0.002). C, a higher average serum HSP90α level was measured in patients with tumor TCF12 mRNA overexpression compared with patients without TCF12 mRNA overexpression in their tumor tissues (348.5 ± 167.1 versus 237.5 ± 78.2 μg/ml, p = 0.001).

Secreted HSP90α Induces CRC Cell EMT, Migration, and Invasion

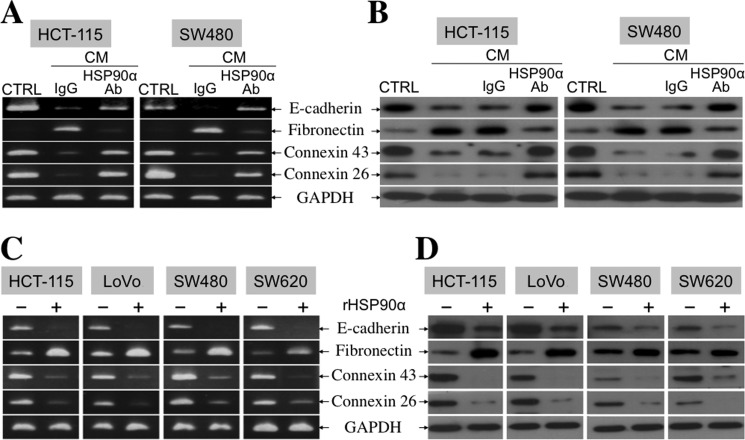

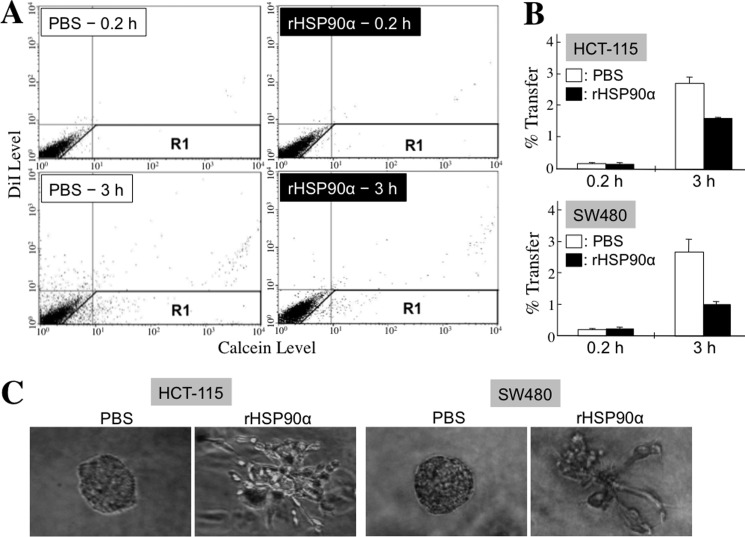

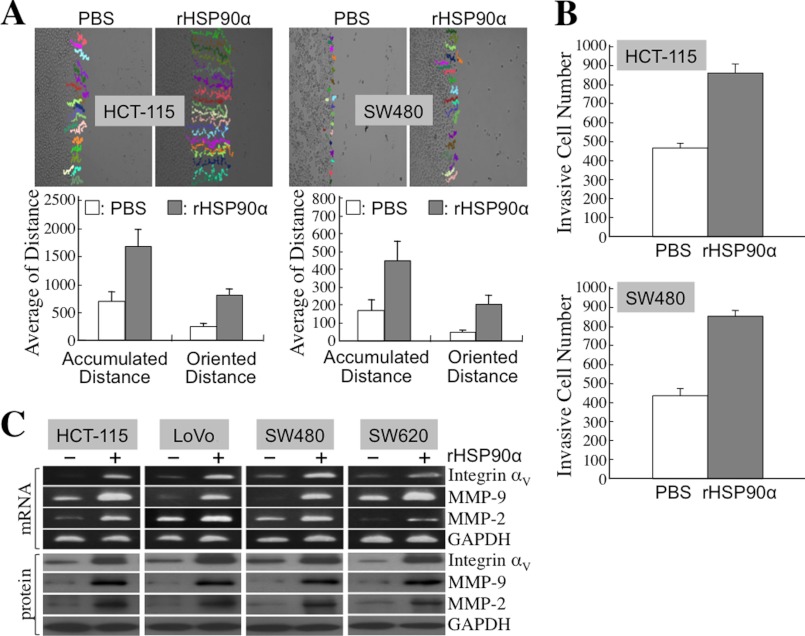

Because TCF12 expression facilitated E-cadherin down-regulation and fibronectin induction, we hypothesized that secreted HSP90α would exert the same effects on cellular expression of EMT hallmark molecules. First, the conditioned media from serum-starved HCT-115 and SW480 cells were collected to treat the corresponding non-serum-starved HCT-115 and SW480 cells, respectively. Fibronectin expression was induced, but E-cadherin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 expression levels were reduced in CM-treated CRC cells. This was significantly reversed by the presence of anti-HSP90α antibody (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting the involvement of HSP90α in the function of the CM. To verify this probability, we exploited purified rHSP90α to treat CRC cell lines. Because 14∼21 μg/ml HSP90α was detected in the CM, we used 15 μg/ml rHSP90α to treat HCT-115, LoVo, SW480, and SW620 cells. Induction of fibronectin expression and simultaneous down-regulation of E-cadherin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 were observed in all tested CRC cells (Fig. 2, C and D). Reduction of gap junction activity, as an efferent event or a functional marker of EMT, was also detected in rHSP90α-treated CRC cells. A representative dot plot of the cellular gap junction assay is shown in Fig. 3A. The quantified data indicate that rHSP90α significantly inhibited the gap junction activities of HCT-115 and SW480 cells (Fig. 3B). The reduction in the E-cadherin level and gap junction activity was consistent with the invasive outgrowths of rHSP90α-treated CRC cells from spherical structures during three-dimensional culture (Fig. 3C). Additionally, rHSP90α enhanced cell migration and invasion activities (Fig. 4, A and B) and increased integrin αV, MMP-9, and MMP-2 levels in CRC cells (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 2.

Secreted HSP90α induces fibronectin expression but represses E-cadherin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 levels in CRC cells. A, RT-PCR was performed to detect E-cadherin, fibronectin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 mRNA levels in HCT-115 and SW480 cells treated for 24 h with serum starvation CM in the presence of preimmune IgG or anti-HSP90α antibody. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. The quantitative data were also obtained using real-time RT-PCR. Taking HCT-115 cells as an example, cellular E-cadherin, connexin-26, and connexin-43 mRNA levels were decreased to 13, 11, and 14%, respectively; however, fibronectin expression was increased to 790% in response to CM plus preimmune IgG. The levels of E-cadherin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and fibronectin mRNA expression could be recovered to 50, 91, 79, and 129%, respectively, when anti-HSP90α antibody was added instead, suggesting that the effects of CM were at least partly attributable to the action of HSP90α secreted in CM. CTRL, control. B, immunoblot analyses were performed to detect E-cadherin, fibronectin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 protein levels in HCT-115 and SW480 cells treated for 24 h with CM in the absence or presence of preimmune IgG or anti-HSP90α antibody. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown. C, RT-PCR was performed to analyze E-cadherin, fibronectin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 mRNA levels in HCT-115, LoVo, SW480, and SW620 cells treated for 24 h with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown. The quantitative data were also obtained using real-time RT-PCR. Taking HCT-115 cells as an example, cellular levels of E-cadherin, connexin-26, and connexin-43 mRNAs were decreased to 9, 24, and 28%, respectively; however, fibronectin expression was increased by 4.2-fold in rHSP90α-treated cells compared with control cells treated with PBS. D, immunoblot analyses were performed to detect E-cadherin, fibronectin, connexin-43, and connexin-26 protein levels in HCT-115, LoVo, SW480, and SW620 cells treated for 24 h with PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown.

FIGURE 3.

rHSP90α inhibits gap junction activity in CRC cells and induces invasive outgrowths of CRC cells from spherical structures during three-dimensional culture. A and B, the Calcein transfer assay was performed to evaluate the effect of rHSP90α on CRC cell gap junction activity. HCT-115 and SW480 cells after 24-h PBS or rHSP90α treatment were labeled with Calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein) and 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) dyes and then added to a monolayer of unstained untreated cells of the same type for 0.2 or 3 h of co-culture. Finally, the monolayer of cells was trypsinized and analyzed by flow cytometry. The dot plots are representative results obtained from HCT-115 cells (A). The cells in the R1 region were categorized as Calcein-accepting cells. The ratio of Calcein-accepting cells (designated as % Transfer) was quantified using CellQuest software, and the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments show that cellular gap junction activity was significantly inhibited after rHSP90α treatment (p < 0.05; B). C, rHSP90α represses the three-dimensional spherical structures assembled by CRC cells. HCT-115 and SW480 cells were cultivated in 2% Matrigel-supplemented medium until spherical structures formed. These cells were then treated with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 72 h. The change in morphology was observed using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope.

FIGURE 4.

rHSP90α enhances CRC cell migration and invasion. A, rHSP90α increases the migration activities of HCT-115 and SW480 cells. Cell migration tracks of rHSP90α-treated or PBS-treated control cells were monitored for 16 h by time-lapse photography and analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software (upper panels). Twenty cells in each treatment group were randomly selected, and their accumulated and oriented migration distances were quantified and expressed as means ± S.D. (lower panels). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments and indicate that cell activity was significantly enhanced by rHSP90α treatment (p < 0.05). B, rHSP90α increases cell invasiveness in HCT-115 and SW480 cells. HCT-115 and SW480 cells were pretreated for 24 h with PBS or rHSP90α and allowed to invade through Matrigel for 16 h. Invasive cells on the filters of the Transwell inserts were counted using Image-Pro Plus software. The means ± S.D. of three independent experiments show that cell invasion activity was significantly enhanced by rHSP90α treatment (p < 0.05). C, RT-PCR and immunoblot analyses were performed to show the induction of mRNA and protein levels of integrin αV, MMP-9, and MMP-2 in HCT-115, LoVo, SW480, and SW620 cells treated for 24 h with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α. Representative data from three independent experiments are shown.

TCF12 Is Involved in rHSP90α-induced EMT of CRC Cells

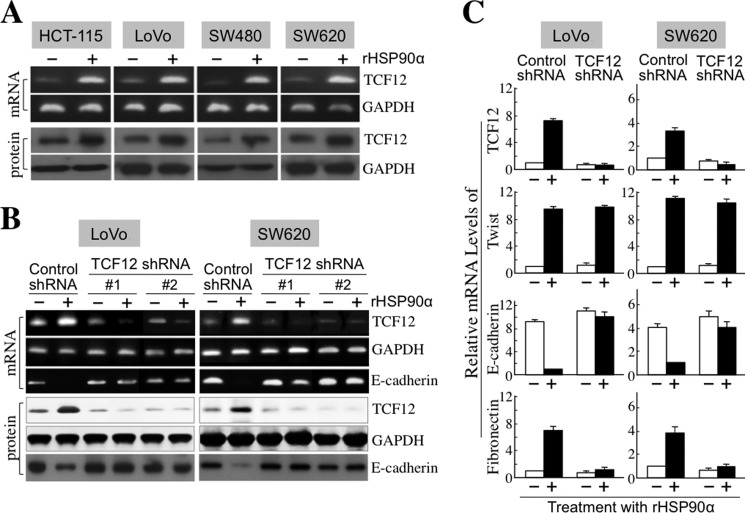

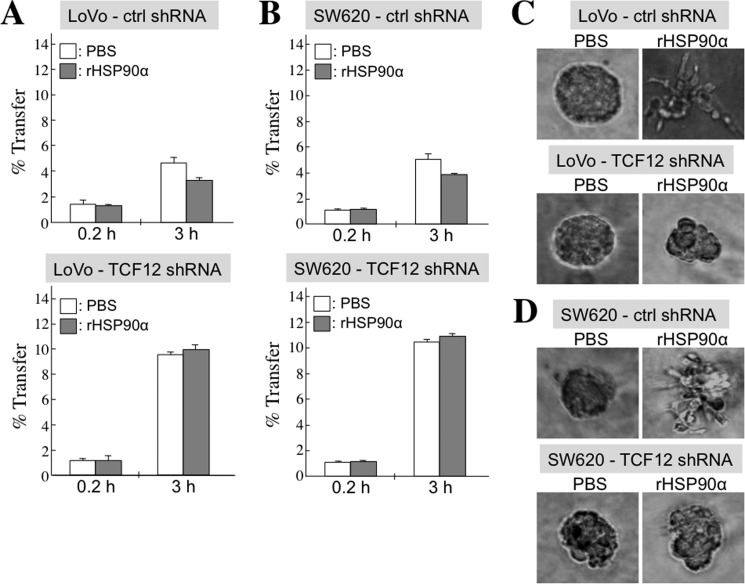

Because TCF12 functions as a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin, we investigated whether rHSP90α could induce TCF12 expression to down-regulate E-cadherin levels. We observed that both the mRNA and protein levels of TCF12 were increased in rHSP90α-treated CRC cells (Fig. 5A). In the stable cell clones of shRNA-mediated TCF12 knockdown from SW620 and LoVo cells, TCF12 was not inducible by rHSP90α (Fig. 5, B and C), whereas another transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin, Twist, was induced (Fig. 5C). This suggests the inhibitory selectivity of TCF12 shRNA. In these TCF12-knockdown cells, rHSP90α-induced E-cadherin down-regulation and fibronectin induction were abrogated (Fig. 5, B and C). The inhibitory effect of rHSP90α on cellular gap junction activity also disappeared in TCF12-knockdown LoVo (Fig. 6A) and SW620 (Fig. 6B) cell clones. Consistently, cellular outgrowths from three-dimensional spherical structures were not induced by rHSP90α in TCF12-knockdown LoVo (Fig. 6C) and SW620 (Fig. 6D) cells. These data together suggest that induction of TCF12 expression is required for the rHSP90α-induced EMT process of CRC cells.

FIGURE 5.

TCF12 is required for rHSP90α-induced E-cadherin down-regulation. A, rHSP90α induces TCF12 expression in CRC cells. RT-PCR and immunoblot analyses were performed to demonstrate that TCF12 mRNA and protein levels were both increased in 15 μg/ml rHSP90α-treated HCT-115, LoVo, SW480, and SW620 cells. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown. B and C, TCF12 knockdown prevents rHSP90α-induced E-cadherin down-regulation. The LoVo and SW620 cell clones stably expressing control shRNA or TCF12 shRNA (sequence 1 or 2) were treated with PBS or rHSP90α. RT-PCR and immunoblot analyses were performed to investigate TCF12 and E-cadherin expression levels. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown in B. TCF12 shRNA sequences 1 and 2 were against nucleotides 986∼1006 and 1727∼1747 of TCF12 mRNA, respectively. The sequence of the control shRNA used did not match any known human gene. Real-time RT-PCR was also performed, and the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are expressed in C to show relative mRNA levels of TCF12, Twist, E-cadherin, and fibronectin in the representative cell clones (stably expressing control shRNA or TCF12 shRNA sequence 1) after treatment with or without rHSP90α.

FIGURE 6.

TCF12 is required for rHSP90α to inhibit CRC cell gap junction activity and to induce invasive outgrowths of CRC cells from three-dimensional spherical structures. A and B, the Calcein assay was performed to evaluate the gap junction activities in representative control (ctrl) and TCF12-knockdown LoVo (A) and SW620 (B) cells after treatment with PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 24 h. Cellular gap junction activity was evaluated by quantifying the ratio of Calcein-accepting cells. The means ± S.D. of three independent experiments revealed that cellular gap junction activity was significantly inhibited by rHSP90α treatment (p < 0.05) only in control (but not TCF12-knockdown) LoVo and SW620 cells, suggesting that induction of TCF12 expression is required for rHSP90α-induced inhibition of cellular gap junction activity. C and D, cell invasive outgrowths from three-dimensional spherical structures were significantly induced by rHSP90α only in control (but not TCF12-knockdown) LoVo (C) and SW620 (D) cells. Cells were cultivated in a three-dimensional culture manner as described above and treated with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 72 h. The results suggest that TCF12 expression is required for rHSP90α to repress cell-cell junctions and spherical structures in CRC cells.

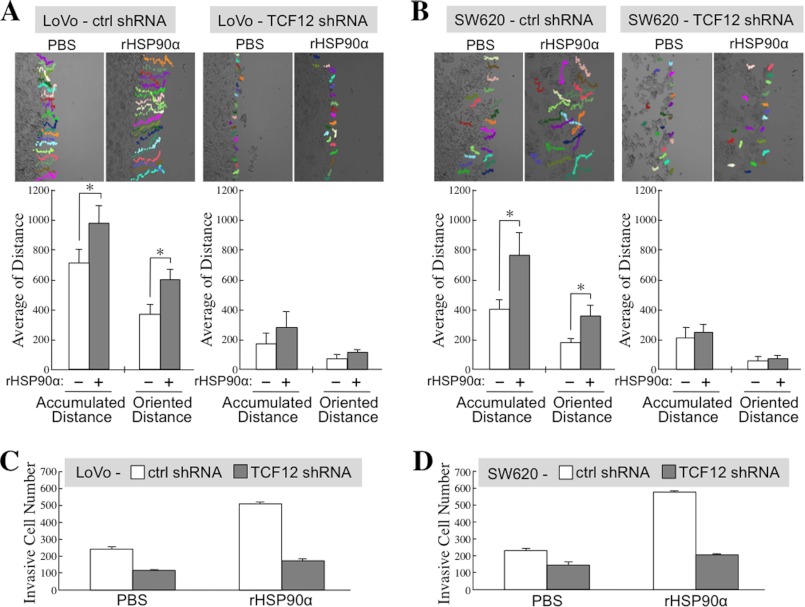

TCF12 Is Involved in rHSP90α-induced CRC Cell Migration and Invasion

We investigated the association of TCF12 expression with CRC cell migration and invasion. Cell migration activity was drastically reduced in TCF12-knockdown LoVo (Fig. 7A) and SW620 (Fig. 7B) cells compared with control cells. The stimulatory effect of rHSP90α on cell migration was observed only in control cells and not in TCF12-knockdown cells (Fig. 7, A and B). Additionally, Transwell invasion assays were performed, and consistent results were obtained. Cell invasion activity was significantly reduced in TCF12-knockdown LoVo (Fig. 7C) and SW620 (Fig. 7D) cells compared with their corresponding control cells, and the induction of cell invasiveness by rHSP90α was obviously inhibited in the CRC cells with TCF12 knockdown (Fig. 7, C and D). Together, these data suggest that induction of TCF12 expression is required for rHSP90α to stimulate CRC cell migration and invasion.

FIGURE 7.

TCF12 is involved in rHSP90α-induced CRC cell migration and invasion. Cell migration tracks were monitored and analyzed for representative control (ctrl) and TCF12-knockdown LoVo (A) and SW620 (B) cells during incubation with PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 16 h. Twenty cells in each treatment group were randomly selected, and their accumulated and oriented migration distances were quantified and expressed as means ± S.D. The representative results of three independent experiments indicate that rHSP90α-induced CRC cell migration could be significantly prevented by knockdown of cellular TCF12 expression. *, p < 0.05. Additionally, cell invasiveness was investigated by the Transwell invasion assay for control and TCF12-knockdown LoVo (C) and SW620 (D) cells that had been treated for 24 h with PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α. The means ± S.D. of three independent experiments show that rHSP90α-induced CRC cell invasion could be significantly prevented by knockdown of cellular TCF12 expression.

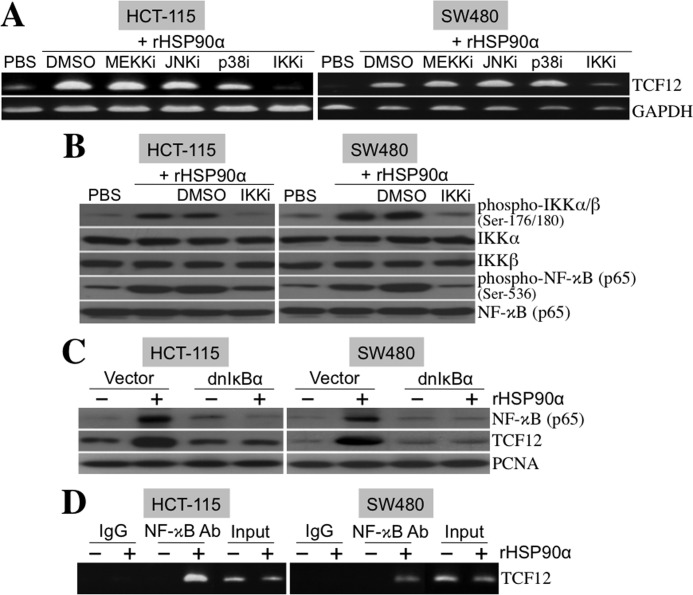

rHSP90α Induces TCF12 Expression through the CD91/IKK/NF-κB Signaling Pathway

We studied the underlying signaling pathway for rHSP90α-induced TCF12 expression. HCT-115 and SW480 cells were treated with rHSP90α in the presence of MEKK, JNK, p38 MAPK, or IKK inhibitor. Even though the activities of these kinases were effectively inhibited by the respective inhibitors (supplemental Fig. 1), only the IKK inhibitor drastically suppressed rHSP90α-induced TCF12 mRNA expression (Fig. 8A), suggesting that the action of rHSP90α is via a NF-κB-dependent pathway. Indeed, the levels of phosphorylated IKKα/β and NF-κB were significantly increased in the CRC cells treated with rHSP90α, and these increases could be effectively abrogated by the presence of the IKK inhibitor (Fig. 8B). Besides the use of the IKK inhibitor, rHSP90α-induced TCF12 expression could also be suppressed by ectopic overexpression of dnIκBα. This IκBα mutant lacked an N-terminal region required for IKK-induced phosphorylation and degradation and therefore could constitutively block NF-κB localization into the nucleus (Fig. 8C). Because the TCF12 gene promoter contains κB sites, we investigated whether NF-κB was physically associated with the TCF12 gene promoter by performing the ChIP assay. As shown in Fig. 8D, NF-κB was physically associated with the TCF12 promoter after induction by rHSP90α treatment. These data together show that rHSP90α induces TCF12 mRNA expression via NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activation.

FIGURE 8.

rHSP90α induces cellular TCF12 expression through the NF-κB-dependent pathway. A, RT-PCR was performed to investigate TCF12 mRNA levels in HCT-115 and SW480 cells treated for 24 h with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α in the presence of inhibitors of MEKK (MEKKi; PD98059, 5 μm), JNK (JNKi; SP600125, 5 μm), p38 MAPK (p38i; SB202190, 5 μm), and IKKα/β (IKKi; 6-amino-4-(4-phenoxyphenylethylamino)quinazoline, 0.1 μm). Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. The data indicate that the IKKα/β inhibitor, but not the others, can drastically abolish rHSP90α-induced TCF12 mRNA expression. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. B, immunoblot analyses of the phosphorylation status of IKKα/β and NF-κB in HCT-115 and SW480 cells treated for 24 h with rHSP90α in the absence or presence of the IKKα/β inhibitor. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown. The data confirm that the IKKα/β inhibitor indeed repressed rHSP90α-induced IKKα/β and NF-κB phosphorylation. C, HCT-115 and SW480 cells were transfected for 48 h with a control vector or dnIκBα-overexpressing plasmid (pRc/CMV-IκB72). Transfected cells were harvested and further treated with PBS or 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for another 24 h. Nuclear extracts were prepared for immunoblot analyses of NF-κB and TCF12 levels. The results show that dnIκBα was efficient in inhibiting rHSP90α-induced nuclear levels of NF-κB and TCF12, confirming that NF-κB is involved in rHSP90α-induced TCF12 expression. The levels of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were used as internal controls. D, the ChIP assay was performed to indicate a physical association of NF-κB with the TCF12 gene promoter in HCT-115 and SW480 cells treated with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α for 24 h. Representative results from three independent experiments are shown.

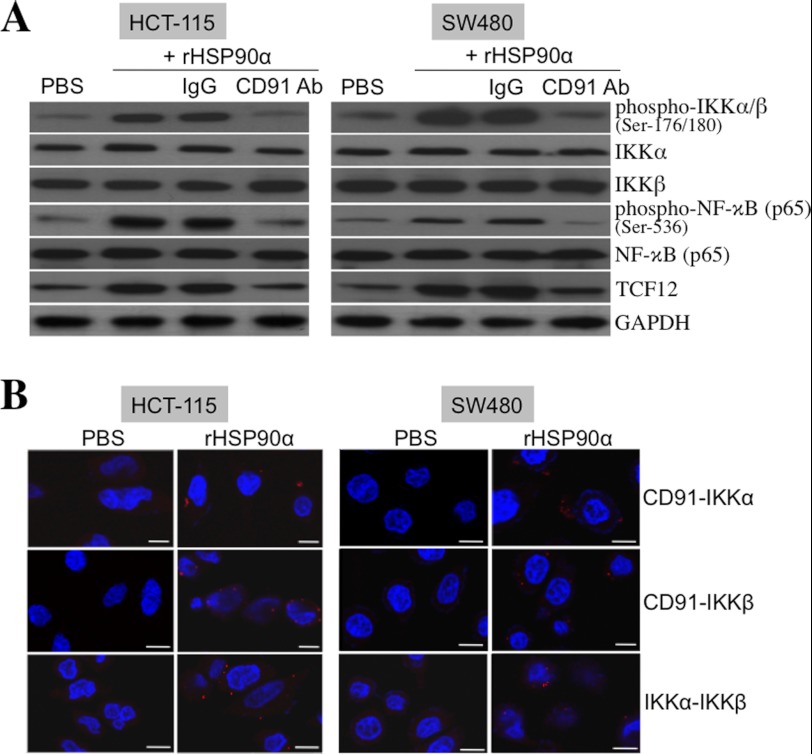

rHSP90α Induces a Physical Association of CD91 with IKKα and IKKβ

CD91 is a cell membrane receptor for extracellular HSP90α. Our results revealed that both TCF12 expression and IKKα/β and NF-κB phosphorylation induced by rHSP90α were effectively inhibited by the antagonizing antibody against CD91 (Fig. 9A), confirming that rHSP90α acts through CD91. We explored whether rHSP90α induces CD91 to recruit IKKα and/or IKKβ to form a physical association and thus to facilitate their phosphorylation and activation. The proximity ligation assay was therefore performed to investigate the molecular interactions among CD91, IKKα, and IKKβ. Red fluorescent dots, representing direct contacts of two different tested proteins, were detected in the CRC cells pretreated with rHSP90α and double-stained with antibodies against CD91 versus IKKα, CD91 versus IKKβ, and IKKα versus IKKβ (Fig. 9B). These data provide evidence that the physical associations between CD91 and IKKα, between CD91 and IKKβ, and between IKKα and IKKβ are induced by rHSP90α in CRC cells. Although Akt is an important kinase for IKKα, the inhibitor of PI3K suppressed rHSP90α-induced Akt phosphorylation but had no obvious inhibitory effect on rHSP90α-induced phosphorylation of IKKα/β and NF-κB (supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting that PI3K and Akt are not involved in rHSP90α-induced CD91/IKK/NF-κB signaling.

FIGURE 9.

rHSP90α induces the NF-κB signaling pathway through the CD91 receptor. A, immunoblot analyses of the phosphorylation status of IKKα/β and NF-κB in HCT-115 and SW480 cells treated for 24 h with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α in the presence of the antagonizing antibody against CD91. Representative results from three independent experiments indicate that rHSP90α-induced IKKα/β and NF-κB phosphorylation could be prevented by anti-CD91 antibody, suggesting that rHSP90α induces IKK signaling through CD91. B, rHSP90α induces a physical association of CD91 with IKKα and IKKβ. HCT-115 and SW480 cells were treated for 24 h with 15 μg/ml rHSP90α and then double-stained with anti-CD91 and anti-IKKα antibodies, with anti-CD91 and anti-IKKβ antibodies, or with anti-IKKα and anti-IKKβ antibodies, followed by the proximity ligation assay. After nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, red fluorescent dots, resulting from the direct contacts of CD91 with IKKα/β and of IKKα with IKKβ, were observed by confocal microscopy.

DISCUSSION

When a solid tumor grows beyond 2 mm in diameter, its inner parts experience nutrient deficiency and hypoxia. Many factors from these regions can stimulate angiogenesis and/or spreading of tumor cells. Secreted HSP90α could be one of these factors. We previously reported that CRC cells are stimulated to secrete HSP90α in response to serum starvation stress and that secreted HSP90α acts as an enhancer of tumor cell migration and invasion (8). In the present study, our data further indicate that secreted HSP90α could facilitate cell EMT by reducing cellular E-cadherin, connexin-26, and connexin-43 expression while inducing fibronectin. EMT is a starting step for the malignant progression of neoplastic cells (13–15). Therefore, secreted HSP90α could function as an initiator of CRC progression. Our clinical data show that the HSP90α levels were elevated in the sera of CRC patients compared with those of normal volunteers. Although the late-stage patients had higher secreted HSP90α levels than the early-stage patients, the difference was not statistically significant, supporting the inference that elevated HSP90α secretion could occur and affect CRC progression from an early stage.

Our studies have demonstrated that both secreted HSP90α and TCF12 overexpression can enhance EMT, migration, and invasion of CRC cells and that tumor TCF12 overexpression is furthermore correlated with the occurrence of CRC metastasis (8, 11). Although the function and cellular effects of overexpressed TCF12 have been described, the mechanisms leading to tumor TCF12 overexpression remained to be investigated. By analyzing 60 CRC patients, we observed that patients with tumor TCF12 overexpression had a higher average serum HSP90α level compared with patients without TCF12 overexpression (348.5 ± 167.1 versus 237.5 ± 78.2 μg/ml, p = 0.001). Therefore, we wondered if secreted HSP90α could induce TCF12 expression to regulate E-cadherin levels and CRC cell migration and invasion. Our data show that rHSP90α induced TCF12 expression in CRC cells, and its effects on cellular expression of E-cadherin, connexin-26, connexin-43, and fibronectin and cellular levels of gap junction, migration, and invasion were significantly abolished in TCF12-knockdown cells. This suggests that TCF12 is involved in the functions of secreted HSP90α. This is the first report to demonstrate that secreted HSP90α could be an extracellular factor stimulating TCF12 overexpression in CRC cells. Elevation of HSP90α secretion could be the underlying mechanism for tumor TCF12 overexpression in CRC patients.

We studied the signaling pathway elicited by secreted HSP90α leading to tumor TCF12 overexpression. Through the cellular receptor CD91, rHSP90α increased the levels of phosphorylated (active) IKKα/β and NF-κB in CRC cells. The small molecule inhibitor of IKKα/β, which efficiently suppressed rHSP90α-induced IKKα/β and NF-κB phosphorylation, could repress rHSP90α-induced TCF12 mRNA expression. Ectopic overexpression of dnIκBα also prevented rHSP90α-induced TCF12 expression by inhibiting NF-κB localization in the nucleus. A physical association of NF-κB with the TCF12 gene promoter was also observed in CRC cells after rHSP90α treatment. These data together confirm that rHSP90α induces TCF12 mRNA expression in an IKK- and NF-κB-dependent manner. IKKα and IKKβ are two catalytic subunits of the IKK complex responsible for the phosphorylation of IκB (16–18). IκB is an inhibitor protein that sequesters and inactivates the transcription factor NF-κB (19, 20). Once IκB is phosphorylated by IKKα/β, it is ubiquitinylated and ultimately degraded, which releases NF-κB to translocate into the nucleus to play the function of a transcription factor. We found that rHSP90α induced the ability of CD91 to recruit IKKα and IKKβ to form a complex. The physical association between IKKα and IKKβ could facilitate phosphorylation and activation of IKKα and IKKβ themselves (21). Together, these results suggest that the CD91/IKK/NF-κB signaling cascade is involved in secreted HSP90α-induced TCF12 mRNA expression in CRC cells.

HSP90 can function as a chaperone responsible for the sustained levels of many oncoproteins (1, 2). Its overexpression has been demonstrated in several human malignancies (22–26). Therefore, many specific inhibitors against the chaperone function of HSP90 have been produced, and they exhibit potent in vitro and in vivo anticancer activities (27). Our studies focused on investigating secreted HSP90α. Secreted HSP90α was significantly increased in CRC patients and functioned to promote cell EMT, migration, invasion, and metastasis via TCF12 expression. Serum HSP90α levels can potentially be used as an adjuvant diagnostic marker and even as a target for CRC therapeutics. Considering that HSP90α is a stress protein overexpressed by malignant cells or normal cells under stress, the inhibitors against the chaperone activity of intracellular HSP90α may cause some cytotoxic side effects in patients. Developing some agents, e.g. specific antibodies or small molecule inhibitors, against secreted HSP90α or TCF12 may be an important direction for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for CRC.

This work was supported by National Science Council Grant NSC101-2314-B-400-006, National Health Research Institutes Grant CA-101-PP-10, and Department of Health Grant DOH102-TD-C-111-004, Taiwan, Republic of China.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

- CRC

- colorectal cancer

- EMT

- epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- rHSP90α

- recombinant HSP90α

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- dnIκBα

- dominant-negative IκBα

- CM

- conditioned medium.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gething M. J., Sambrook J. (1992) Protein folding in the cell. Nature 355, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsutsumi S., Neckers L. (2007) Extracellular heat shock protein 90: a role for a molecular chaperone in cell motility and cancer metastasis. Cancer Sci. 98, 1536–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sidera K., Samiotaki M., Yfanti E., Panayotou G., Patsavoudi E. (2004) A critical role for HSP90 in cancer cell invasion involves interaction with the extracellular domain of HER-2. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 45379–45388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becker B., Multhoff G., Farkas B., Wild P. J., Landthaler M., Stolz W., Vogt T. (2004) Induction of Hsp90 protein expression in malignant melanomas and melanoma metastases. Exp. Dermatol. 13, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eustace B. K., Sakurai T., Stewart J. K., Yimlamai D., Unger C., Zehetmeier C., Lain B., Torella C., Henning S. W., Beste G., Scroggins B. T., Neckers L., Ilag L. L., Jay D. G. (2004) Functional proteomic screens reveal an essential extracellular role for hsp90α in cancer cell invasiveness. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu A., Tian T., Hao J., Liu J., Zhang Z., Hao J., Wu S., Huang L., Xiao X., He D. (2007) Elevation of serum HSP90α correlated with the clinical stage of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Mol. 3, 107–112 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang X., Song X., Zhuo W., Fu Y., Shi H., Liang Y., Tong M., Chang G., Luo Y. (2009) The regulatory mechanism of HSP90α secretion and its function in tumor malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21288–21293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen J. S., Hsu Y. M., Chen C. C., Chen L. L., Lee C. C., Huang T. S. (2010) Secreted heat shock protein 90α induces colorectal cancer cell invasion through CD91/LRP-1 and NF-κB-mediated integrin αV expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25458–25466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Basu S., Binder R. J., Ramalingam T., Srivastava P. K. (2001) CD91 is a common receptor for heat shock proteins gp96, hsp90, hsp70, and calreticulin. Immunity 14, 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gopal U., Bohonowych J. E., Lema-Tome C., Liu A., Garrett-Mayer E., Wang B., Isaacs J. S. (2011) A novel extracellular Hsp90 mediated co-receptor function for LRP1 regulates EphA2-dependent glioblastoma cell invasion. PLoS ONE 6, e17649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee C. C., Chen W. S., Chen C. C., Chen L. L., Lin Y. S., Fan C. S., Huang T. S. (2012) TCF12 functions as a transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin, and its overexpression is correlated with the metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2798–2809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang T. S., Shu C. H., Yang W. K., Whang-Peng J. (1997) Activation of CDC25 phosphatase and CDC2 kinase involved in GL331-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 57, 2974–2978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peinado H., Olmeda D., Cano A. (2007) Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thiery J. P., Acloque H., Huang R. Y. J., Nieto M. A. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139, 871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Voulgari A., Pintzas A. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer metastasis: mechanisms, markers and strategies to overcome drug resistance in the clinic. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1796, 75–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Régnier C. H., Song H. Y., Gao X., Goeddel D. V., Cao Z., Rothe M. (1997) Identification and characterization of an IκB kinase. Cell 90, 373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zandi E., Rothwarf D. M., Delhase M., Hayakawa M., Karin M. (1997) The IκB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, necessary for IκB phosphorylation and NF-κB activation. Cell 91, 243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zandi E., Chen Y., Karin M. (1998) Direct phosphorylation of IκB by IKKα and IKKβ: discrimination between free and NF-κB-bound substrate. Science 281, 1360–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baeuerle P. A., Baltimore D. (1996) NF-κB: ten years after. Cell 87, 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baldwin A. S. (1996) The NF-κB and IκB proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14, 649–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamamoto Y., Yin M. J., Gaynor R. B. (2000) IκB kinase α (IKKα) regulation of IKKβ kinase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 3655–3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neckers L. (2002) Heat shock protein 90 is a rational molecular target in breast cancer. Breast Dis. 15, 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lebret T., Watson R. W., Molinié V., O'Neill A., Gabriel C., Fitzpatrick J. M., Botto H. (2003) Heat shock proteins HSP27, HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90: expression in bladder carcinoma. Cancer 98, 970–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhong L., Peng X., Hidalgo G. E., Doherty D. E., Stromberg A. J., Hirschowitz E. A. (2003) Antibodies to HSP70 and HSP90 in serum in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Detect. Prev. 27, 285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cappello F., David S., Ardizzone N., Rappa F., Marasà L., Bucchieri F., Zummo G. (2006) Expression of heat shock proteins HSP10, HSP27, HSP60, HSP70, and HSP90 in urothelial carcinoma of urinary bladder. J. Cancer Mol. 2, 73–77 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen W. S., Lee C. C., Hsu Y. M., Chen C. C., Huang T. S. (2011) Identification of heat shock protein 90α as an IMH-2 epitope-associated protein and correlation of its mRNA overexpression with colorectal cancer metastasis and poor prognosis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 26, 1009–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goetz M. P., Toft D. O., Ames M. M., Erlichman C. (2003) The Hsp90 chaperone complex as a novel target for cancer therapy. Ann. Oncol. 14, 1169–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]