Introduction

The importance of intermediary metabolism to sustain function of the heart has long been appreciated. For example, it is known early in the 1900s that oxidative metabolism of energy providing substrates is essential for the pump function of the heart. (1) Only much more recently, has it become possible to assess cardiac metabolism both non-invasively and dynamically. However, even the most sophisticated techniques can still assess only the proverbial “tip of the iceberg”. (2)

Much progress has been made during the last half century in imaging the cardiovascular system. However, the needs for the early detection and management of most forms of heart disease are still not completely met. Quantitative methods that integrate cardiovascular physiology and metabolism should be able to meet this challenge. Recent advances in this field are both conceptual and technical. For example, in the stressed heart metabolic remodeling precedes, triggers and maintains functional and structural remodeling. (3) At the same time much has been learned about the biochemical derangements underlying metabolic and structural remodeling of the heart.

The bewildering network of pathways of intermediary metabolism is well documented in any textbook of biochemistry. For our purposes the principles of cardiac metabolism can be more easily understood if approached from the following vantage point: in the myocardial cell, a series of enzyme-catalyzed reactions result in the efficient transfer of chemical energy into mechanical energy. Despite the biochemical complexity involved in this transaction, the overall activity of metabolic pathways (or flux through the pathways) can be readily traced throughout the entire heart. I will therefore begin our exploration into the subject of cardiac metabolism with a brief overview of the key substrates utilized for energy provision, then focus on the metabolic tracers which can be used to non-invasively view these reactions in vivo and methods to visualize them. The ultimate goal of this discussion is to emphasize the ability of isotopic tracers to detect the metabolic footprints of heart disease and propose that cardiac metabolic imaging is more than a useful adjunct to current myocardial perfusion imaging studies. The goal is that metabolic imaging leads to targeted, non-invasive information as a basis for interventions in the treatment of heart disease, including ischemia, hypertrophy, and heart failure.

Metabolism: A Book with Many Chapters

Cardiac metabolism is a book with many chapters, all expounding on the following principal theme: the dynamic state of energy transfer and the dynamic state of functional proteins that constitute the myocardium itself. The former describes intermediary metabolism while the latter refers to the turnover of myocardial proteins, most of which are enzymes, contractile elements, receptors or transporters.

Metabolic imaging uses the tools of radionuclide tracers or magnetic resonance to trace either flux of energy providing substrates or steady state concentrations of metabolites by non-invasive methods. While there are non-invasive methods to assess receptor physiology, reliable methods for the noninvasive assessment of myocardial protein turnover are currently not available.

Transfer of Energy –Prime Mover of Metabolism

As already stated, the key function of intermediary metabolism is the regulated, controlled transfer of chemical energy to ATP and, by implication, to contraction of the heart muscle. (4) This is a complex process, the details of which were discovered over a period of many years and include three phases: pathway identification (up until the 1950s), pathway regulation (up until the 1990s), and quantification of pathway fluxes (until present). Pathway identification dates back to the discovery of the first law of thermodynamics. In his experiments on the chemistry of muscle contraction, Helmholtz observed that a chemical transformation of the compounds within the muscle itself was necessary for muscular contraction. (5) Within the cardiovascular system, the myocardium requires an uninterrupted supply of energy providing substrates in order to support rhythmic contractions. (6) It is the oxidative metabolism of energy providing substrates that provides this energy, and the amount of energy used is controlled by the oxygen demands of the myocardium.

As an organ designed for continuous, rhythmic aerobic work under constantly changing environmental conditions, the heart utilizes a variety of oxidizable substrates for energy provision. Acute changes in myocardial energy demands are met by changes in flux through existing metabolic pathways. (3, 7) In contrast, with chronic changes in its environment the heart adapts to chronic conditions by changing the rates of synthesis and degradation of the enzyme proteins that constitute the catalysts of metabolic pathways. (8) The bottom line is: Through these complex and highly regulated mechanisms, the heart manages to maintain a balance of energy supply proportional to its needs.

Using a variety of available methods for assessing metabolic activity of the heart, such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), both investigators and physicians are able to identify metabolically, heart muscle tissue that is reversibly dysfunctional compared to tissue which is irreversibly so. For this reason, the last decade has witnessed renewed interest in cardiac metabolism. For example, we have proposed that metabolic changes often antedate functional contractile changes, and that these changes can be traced by non-invasive imaging methods. (3) Others have shown that in the human heart glucose utilization is inversely proportional to fatty acid utilization by the heart (9) and that in the heart of obese women increased myocardial oxygen consumption is associated with a decrease in efficiency. (10) Another, already well established, hypothesis is that metabolic activity correlates to viability of stressed or injured myocardial tissue. (8) The end point of both of these lines of reasoning is that non-invasive imaging techniques can be used to evaluate these metabolic changes in order to assess the “health” of the heart.

Metabolic Cycles

The greater the cardiac output, the higher the rate of substrate utilization to provide for the increase in oxygen demand. Increased rates of oxygen consumption are directly correlated with increased rates of coronary blood flow. An important principle is that myocardial energy metabolism is not reflected by the tissue content of ATP, but rather by the rate of ATP turnover. (11)

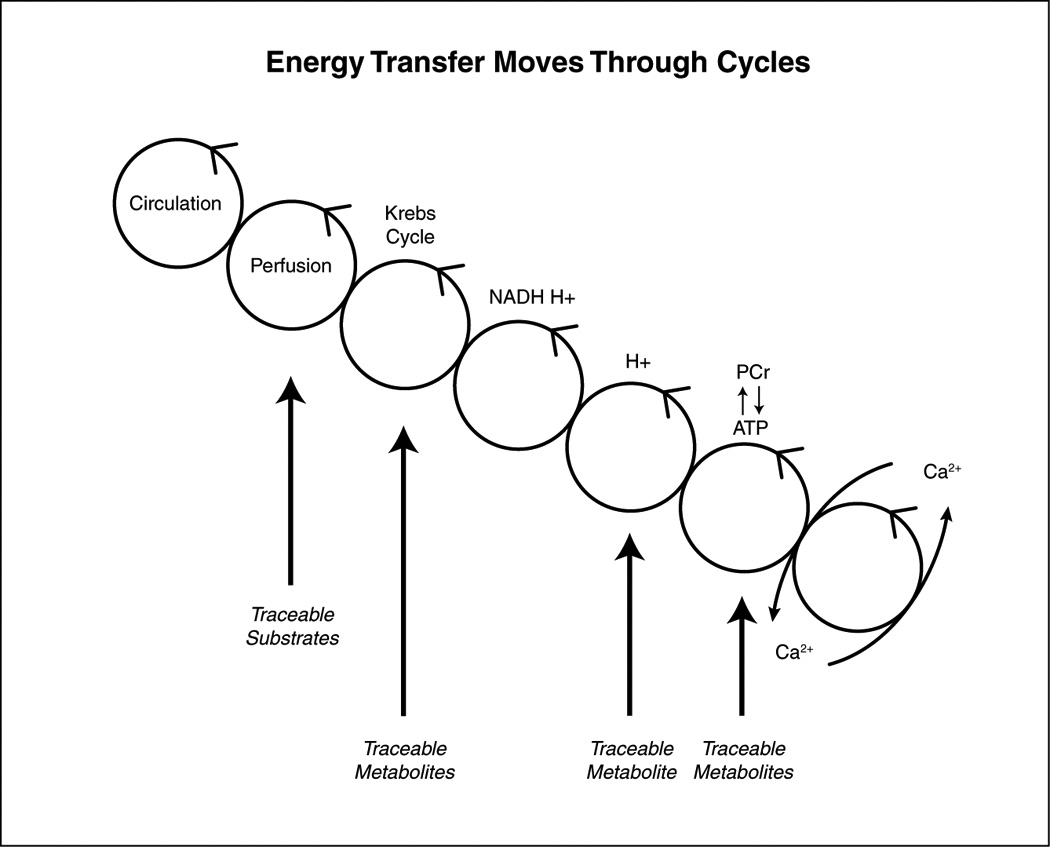

Irrespective of the kind of substrate, the most efficient forms of energy transfer moves through a series of interconnected cycles (Figure.1) which improve the efficiency of energy transfer. In this scheme energy transfer begins with cycles (systemic circulation and perfusion) and ends with cycles (cross bridges of the sarcomeres). (4, 12) The metabolic pathways inside the cell include several interconnected cycles, most notably the Krebs cycle, the proton gradient in the respiratory chain, and the ATP cycle. Metabolic cycles transform substrates into usable energy via a series of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. As Figure 1 shows, tracers for perfusion (201thallium, 82Rb, 13NH3), Krebs cycle activity (11C-acetate), proton production (1H1), and high energy phosphates (31P) are either intermediary metabolites or substrates for metabolic activity. Metabolic imaging cannot image the cycles themselves, but it can assess flux through the overall pathway of cycles instead.

Figure 1.

The transfer of energy from the coronary circulation to the contractile elements (crossbridges) moves through a series of moiety-conserved cycles. Substrates and metabolites can be traced by non-invasive methods. See text for further detail.

Opportunities for Imaging Metabolism

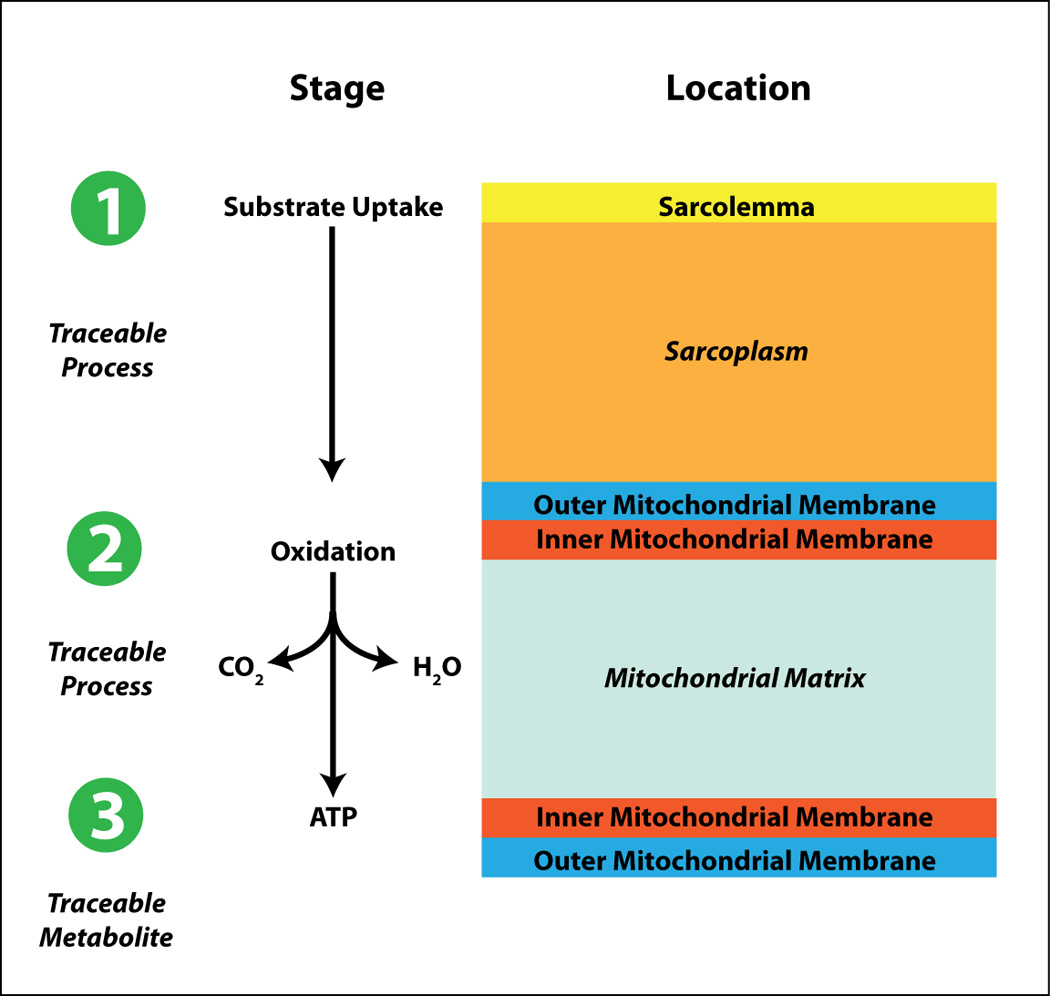

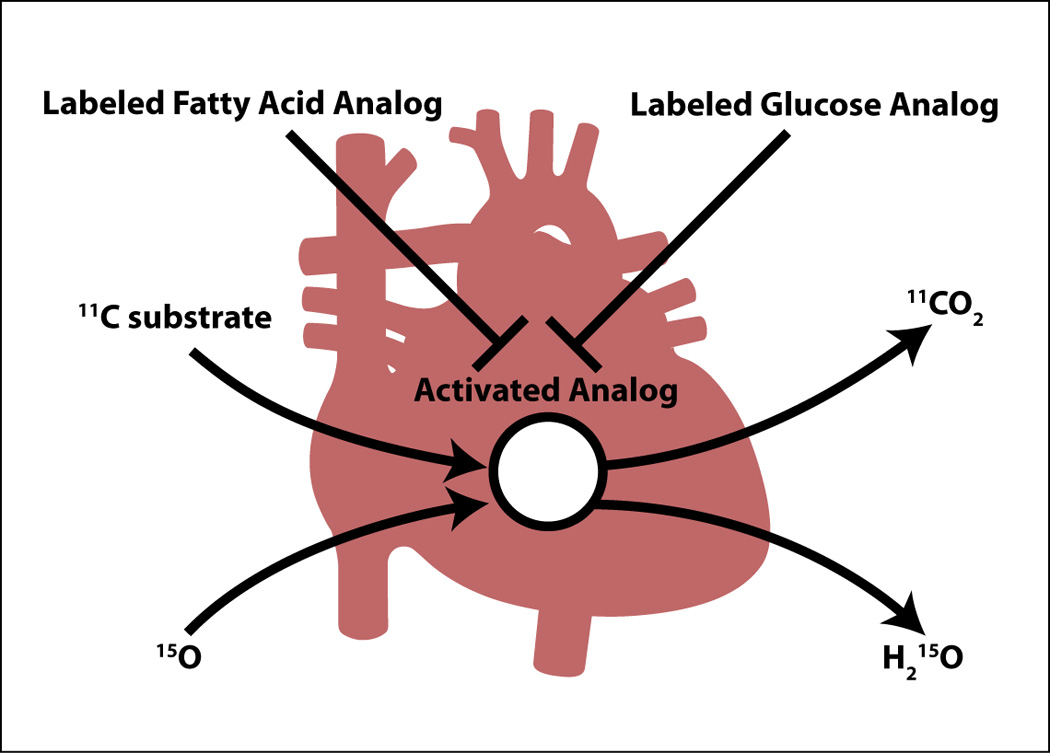

The heart is a metabolic omnivore, i.e. it feeds on a variety of substrates. (13) Its metabolic machinery has the capacity to produce ATP from many different substrates, chiefly from fatty acids and glucose. (6) The breakdown of substrates can be divided into several stages (Figure 2). Each of the stages can be selectively probed with positron-labeled tracers (substrates, acetate, and oxygen) or with stable isotopes (13C and 31P). The first stage [1] of this process is the uptake of substrate by the cell for metabolism in a pathway, the end products of which include acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA). The second stage [2] consists of oxidation of acetyl-CoA and the subsequent generation of reducing equivalents and CO2 (in the Krebs cycle). The third stage [3] consists of the reducing equivalents generated in stage II undergoing a reaction with molecular oxygen in the respiratory chain, where electron transfer is coupled to re-phosphorylation of ADP to ATP. Table 1 lists a number of positron labeled tracers and tracer analogs available to clinicians and investigators for the assessment of the three stages of energy substrate metabolism in the heart (or any other organ in the living mammalian organism). As Figure 3 shows there are tracers for assessment of myocardial perfusion, of substrate uptake and retention (e.g., the glucose tracer analog 18FDG, or the long-chain fatty acid tracer analog), tracers that assess flux of entire metabolic pathways, and tracers for the assessment of citric acid cycle flux. Metabolic activity in the heart is highly regulated and strongly influenced by the physiologic environment. All these factors affect tracer activity in vivo. The following paragraphs illustrate this point by comparing mechanisms of metabolic regulation unraveled ex vivo (through perfusion experiments) or in vivo (through transgenesis) to findings obtained with metabolic imaging techniques (mostly PET) in humans or animal models of disease. To state the main point up front: For the most part it is not difficult to translate the findings from the laboratory to the human heart and vice versa. Some of the principles of substrate metabolism by the heart will now be discussed in detail.

Figure 2.

Substrate metabolism in the heart can be divided into substrate uptake and metabolism [1], oxidation [2], and ATP production [3]. Each state can be traced. See text for further detail.

Table 1.

Tracer/Tracer Analogs and Metabolic Processes They Identify

| Tracer | Metabolic Process |

|---|---|

| 11C-glucose | Glucose metabolism (uptake, glycolysis, glycogen synthesis, oxidation) |

| 11C-palmitate | Long, straight-chain fatty acid uptake, triglyceride synthesis, and fatty acid oxidation |

| 11C-B-methyl heptadecanoic acid (BMHDA) | Long chain and branched-chain fatty acid uptake |

| 11C-lactate | Lactate oxidation |

| 11C-acetate | Acetate Oxidation; Oxygen consumption |

| 15O O2 | |

| 11C-MeAIB [N-methyl-11C]alpha methylaminoisobutyric acid | Amino acid oxidation |

| 11C-glutamate | |

| 11C-aspartate | |

| 13N-glutamate | |

| 13N Ammonia | Myocardial perfusion (metabolic trapping) |

| 38K (Potassium) | Myocardial perfusion (ion pump) |

| 81Rb or 82RB (Rubidium) | |

| 52Mn (Manganese) | Myocardial perfusion (diffusion) |

| 15O H2O | |

| [18F] 2-deoxy-2-fluoroglucose (FDG) | Glucose uptake (transport and phosphorylation) |

| [18F] Fluoro-6-thia-heptadecanoic acid (FTHA) | Long, straight-chain fatty acid uptake |

| [123I]-iodophenylpentadecanoic acid (IPPA) | |

| [18F] Fluoro-4-thia-palmitate (FTP) | |

| [18F] Fluoro-3,4-methylene-heptadecanoic acid (FCPHA) | |

| [123I]-B-methyl-p-iodophenyl-pentadecanoic acid (BMIPP) | Long, branched-chain fatty acid uptake |

| [123I]-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) | Adrenergic receptor metabolism |

| (S)-[18F]-fluoroethylcarbozol | |

| 64Cu-ATSM [diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazonel)] | Hypoxia |

| 18F-fluoromisonidastole | |

Figure 3.

Positron labeled tracer analogs for either fatty acids or glucose are transported into the heart muscle cell and retained, while positron labeled tracer substrates (11C-compounds and 15O2) are taken up, metabolized and released (as either 11CO2 or H215O). See text for further details.

Fatty Acid Metabolism and Substrate Interaction

In the post-prandial state and under resting conditions, long-chain fatty acids are the main fuel source for the heart. (14) Fatty acids suppress glucose oxidation at the level of the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). (15, 16) Transcriptionaly, long-chain fatty acid oxidation is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα), a nuclear receptor that binds to peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) to up-regulate the transcription and translation of genes for all the enzymes involved in the β-oxidation of fatty acids. (17) The main orchestrator of this complex is, however, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator PGC1α. (18, 19) The discovery of the PGC-1 family of coactivators (20) led to the identification of PGC1α as inducer of mitochondrial biogenesis and, consequently, the tightly coupled respiration to high rates of ATP production in the heart. (21) The critical role of PGC1α in the physiological control of myocardial energy substrate metabolism has recently been elegantly reviewed. (22)

However, the heart also uses a storage system of endogenous substrates (glycogen and triglycerides) in order to buffer changes in the dietary or hemodynamic state. (23, 24) For example, with an acute increase in workload of the isolated working rat heart, there is a resulting acute increase in myocardial oxygen consumption and CO2 production. (25) During this process, the heart oxidizes carbohydrates to meet the increased energy demands for contraction. Although long-chain fatty acids are the predominant fuel for energy provision for the mammalian heart in the normal state, carbohydrates are the fuel for the fetal heart (26) and for the adult heart in a state of exercise or stress. (27) In the stressed heart in vivo, the efficiency of glucose as substrate exceeds the efficiency of fatty acids as substrate by as much as 40%. (28) This “metabolic flexibility” is an inherent property of the normal heart, and the relative predominance of a fuel for respiration depends on its arterial substrate concentration, on hormonal influences, workload, and oxygen supply. Simply put, it seems that for a given environment the heart oxidizes the most efficient substrate. (28)

While plasma fatty acid and triglyceride levels vary depending on the dietary state of the whole organism, fluctuations in plasma glucose levels are relatively minor and tightly controlled by insulin. Under resting conditions glucose contributes about 30% of the fuel for respiration to the heart, (6, 29, 30) mostly through the generation of acetyl-CoA. There is, however, also carboxylation of pyruvate, and pyruvate derived from glucose serves as an anaplerotic substrate for the Krebs cycle. (31) Anaplerosis, which means “filling up” of cycle intermediates is a pre-requisite for normal cycle flux, (32, 33) and essential for the initiation of fatty acid oxidation in the heart. (34)

In the normal, non-diabetic mammalian organism, glucose levels in the blood are tightly regulated at around 5mM (or 90 mg%). When the normal heart is stressed, it oxidizes first glycogen, then glucose and lactate; (35) thus with exercise and the subsequent depletion of glycogen stores, blood lactate levels rise and replaces all other substrates as fuel for the heart. Furthermore, element isotopic tracer studies have shown that the normal human heart simultaneously produces and oxidizes lactate, as well as it utilizes glucose to form glycogen when the body is in a fasted, resting state. (31) In elegant tracer kinetic studies of human heart it has been estimated that half the amount of exogenous glucose is shunted first into glycogen before it is oxidized. (36) Glucose and lactate extraction by the heart rises with an increase in workload, even in the presence of competing substrates both in vivo, (37) and ex vivo. (25) This observation is of interest given the fact that pyruvate is the common metabolic product of glucose, glycogen, and lactate metabolism, and that pyruvate competes effectively for the fuel of respiration. The likely mechanism involves inhibition of carnitine palmityl transferase I (CPTI) by malonyl-CoA. (25, 38, 39) With sustained inotropic stimulation of the heart, however, rates of fatty acid oxidation increase, most likely by activation of the enzyme malonyl-CoA decarboxiylase and de-inhibition of CPTI. (40)

Imaging Glucose and Fatty Acid Metabolism

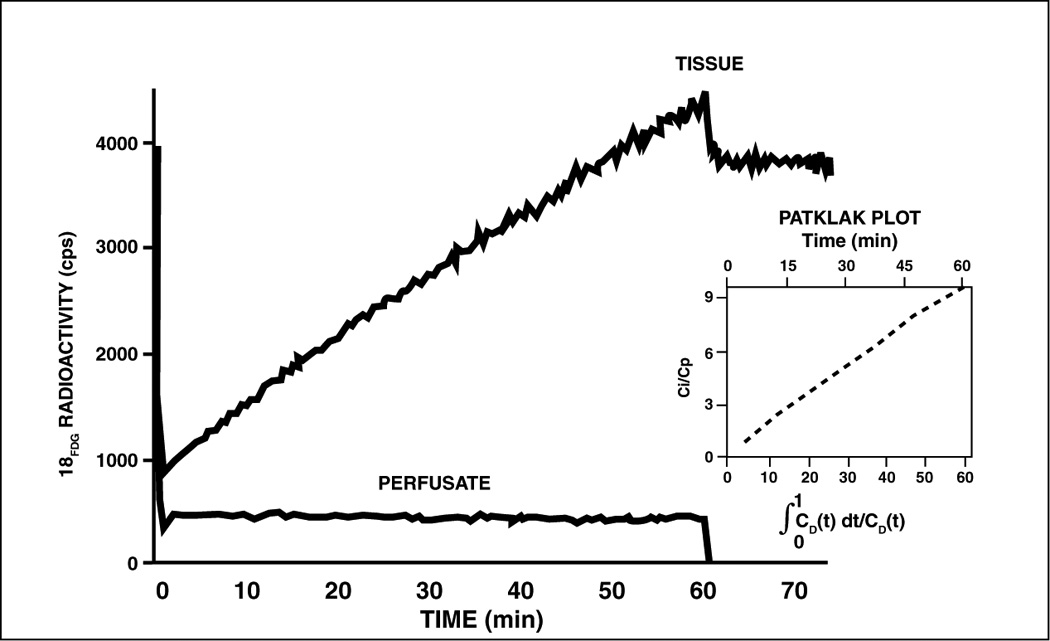

Tracers for the assessment of glucose metabolism in the intact heart include [11C] glucose and the glucose tracer analog [18F] 2-deoxyglucose (FDG) (Figure 4). FDG is phosphorylated by hexokinase to FDG6-phosphate but is not metabolized further in the glycolytic pathway, and is thus trapped within the myocardium. Increased uptake of glucose and, therefore, FDG by ischemic myocardium occurs in response to ischemic ATP depletion, with the aim of maintaining cellular viability. (41)

Figure 4.

Progressive accumulation of the glucose tracer analog 18F-2-deoxyglucose by an isolated working rat heart perfused with Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate saline containing glucose (5mM) as substrate. The input function (radioactivity in the perfusate) was stable (lower curve). At time 60 min perfusate was switched to the same saline without the tracer analog (lower curve). The tissue retention of the tracer analog was stable (upper curve). Cardiac work was the same throughout the experiment. See text for further detail. (Adapted from (42)).

The tracer analog technique to assess glucose transport and phosphorylation has been validated in the isolated working rat heart where FDG accumulates in a linear fashion and is retained when the perfusate is switched to tracer-free medium (right side of the diagram Figure 4). (42) Quantification of myocardial glucose uptake requires a stable tracer/ trace ratio, and a stable “lumped constant” (LC), which is a correction factor in the tracer kinetic model for the assessment of glucose uptake and phosphorylation by 2-deoxyglucose accounting for differences between FDG and natural glucose. It consists of six separate constants and was first developed for brain studies. (43) Although it is assumed that the LC is constant in the heart in situ, the LC changes under non-steady-state conditions, e.g., with the administration of insulin (44) and with reperfusion after ischemia, (45) and we have proposed a tracer kinetic model that takes into account changes of the LC under nonsteady state conditions. (46) Similar considerations involving an LC and its variability also apply to tracer analogs of fatty acids such as 18F-labeled 4-thia palmitate, and 15[18F] fluoro-3-oxapentadecanoate, which have been used to assess derangements of myocardial fatty acid metabolism in heart failure. (47) Rates of glucose metabolism can be directly assessed with the tracer [11C]-glucose, which provides accurate quantification of myocardial glucose utilization in vivo. This approach is much more demanding for the investigator because it requires blood sampling with metabolite analysis. Very few laboratories are capable to perform this protocol. (48) FDG remains, therefore, the most popular method for assessment of myocardial glucose metabolism.

FDG uptake by the heart is dependent on glucose concentration in the plasma, rate of glucose delivery to the heart and the rate of glucose utilization by the heart muscle cell. An elevated plasma glucose concentration will decrease the fractional extraction of FDG and thus decrease the quality of the myocardial FDG uptake image. (49, 50) In addition, studies have shown that certain conditions can enhance FDG uptake by increasing regional glucose utilization. Such factors include an increase in myocardial work, catecholamines, or a decrease in plasma levels of free fatty acids (FFAs). (4, 51) The most important reason for an increase in regional myocardial glucose uptake is, however, reprogramming of hibernating myocardium to the fetal gene program. (52–55) There have been many attempts to standardize the metabolic environment for myocardial FDG imaging with PET. These include oral glucose loading (50–75g) to stimulate insulin secretion by the β-cells. Studies have shown that oral glucose loading has a positive effect on image quality with a more homogeneously distributed tracer analog in comparison to a fasting state. (56) However, it was already mentioned previously that an increase in glucose concentration can lower the fractional utilization of FDG and decrease the quality of the image, thus counteracting the positive effect of increased regional glucose utilization. Patients with coronary artery disease, especially with underlying diabetes, will still have poor image quality with oral glucose loading. (56) A little know alternative to FDG imaging in myocardial ischemia is enhanced [13N] glutamate uptake. (57) However, this method awaits further development.

The euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp is an approach that mimics the post-absorptive steady-state, has thus become an alternative approach to oral glucose loading for enhancing glucose and FDG utilization. (49, 58) Even in patients with diabetes, insulin clamping has yielded myocardial molecular images of high diagnostic value. (59) However, similar degrees of glucose uptake variability exist between oral glucose loading and insulin clamping, most likely secondary to the variability in FFA and lactate levels. (59) A relatively easy approach to reduce plasma FFA concentrations and improve image quality is the oral administration of nicotinic acid which inhibits peripheral lipolysis. (50, 60)

To conclude this section, both the complexity and the magnitude of myocardial energy metabolism can be overwhelming if not approached systematically beginning at the cellular level. Mitochondrial metabolism provides the human heart with more than 5 kg of ATP per day. (51) In addition to the network of energy transfer of the heart, recent studies have stressed the diverse functions of cardiac metabolism. Besides providing energy for muscle contraction, the metabolism of substrates (fatty acids, carbohydrates, amino acids, and even adenine nucleotides) also provides signals for growth, gene expression, apoptosis, and programmed cell survival. While the role of metabolic signaling in myocardial stunning and hibernation has already been recognized, (61) its role in cardiac growth and gene expression has not yet been systematically addressed. Here metabolic imaging may be in a unique position to shed light on some of the unanswered questions regarding both short- and long-term adaptation of the heart to various forms to stress. (62)

Imaging Metabolic Adaptation and Maladaptation of the Heart

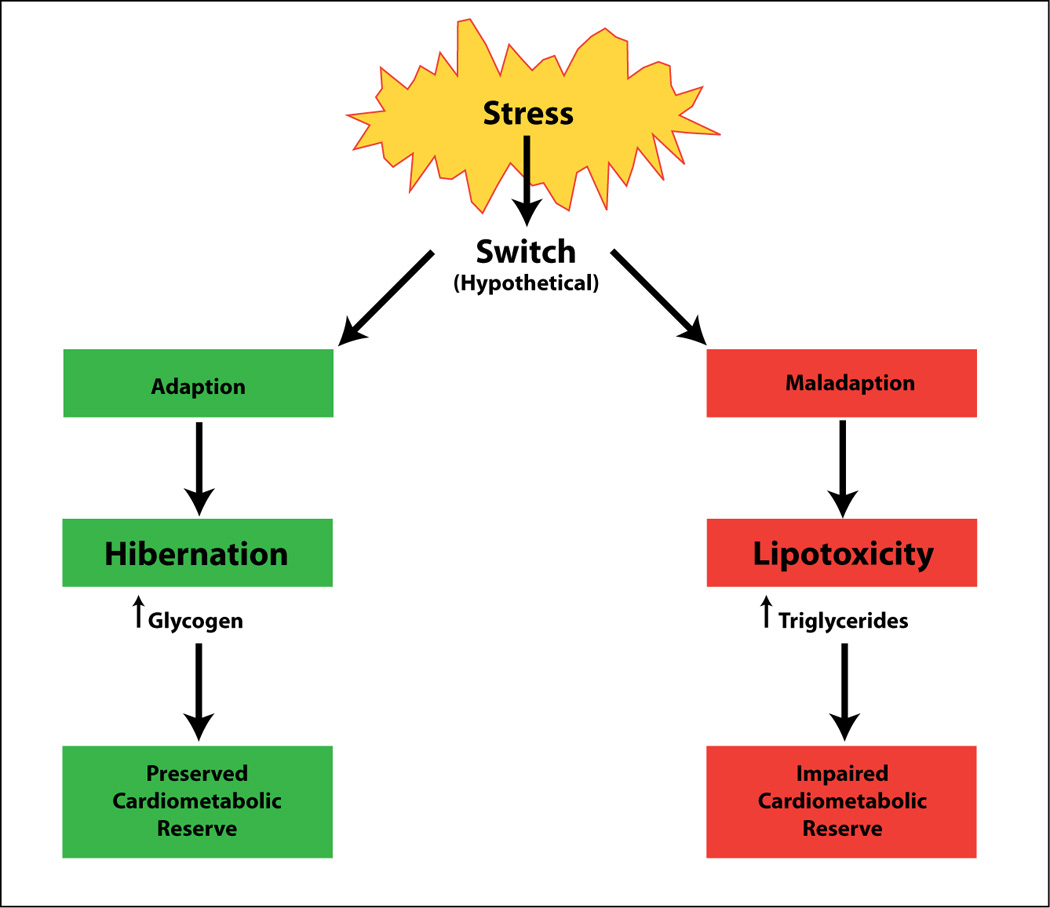

The heart adapts or maladapts in response to changes in its physiologic environment. (Figure 5) Here the physiologic environment of the heart includes the hemodynamic, the metabolic, and the circulatory environment. Like Opie and Sack, who introduced the concept of metabolic plasticity, (63) we have argued that changes in the environment of the heart give rise to specific metabolic signals affecting cardiac structure and function. (64)

Figure 5.

Adaptive and maladaptive stress responses of the myocardium. The adaptive response of myocardial hibernation has distinctly different features from the maladaptive response of myocardial lipotoxicity. Both processes can be traced by non-invasive methods. See text for further detail. (Adapted from (64)).

Perhaps the most dramatic example of chronic metabolic adaptation is hibernating myocardium. Hibernating myocardium represents a chronically dysfunctional myocardium and is most likely the result of extensive cellular reprogramming due to repetitive episodes of ischemia or chronic hypoperfusion. (65) Functionally hibernating myocardium is characterized by an improvement of contractile function with reperfusion or inotropic stimulation. Metabolically hibernating myocardium is characterized by a switch from fat to glucose metabolism, accompanied by reactivation of the fetal gene program. (66) Because glucose transport and phosphorylation is readily traced by the uptake and retention of FDG, hibernating myocardium is readily detected by enhanced glucose uptake and glycogen accumulation in the same regions. (67) Although rates of glucose oxidation are reduced, the glycogen content of hibernating myocardium is dramatically increased. (68) There is a direct correlation between glycogen content and myocardial levels of ATP, (69) and one may be tempted to speculate that improved “energetics” is the result of improved glycogen metabolism in hibernating myocardium. However, the true mechanism for “viability remodeling” of ischemic myocardium is likely to be much more complex, and there is good evidence for the activation of a gene expression program of cell survival. (68) The similarities between the hibernating and the fetal myocardium suggest an innate mechanism of myocardial protection. In time, molecular imaging may shed more light on this process.

A fitting example for chronic metabolic maladaptation is the lipotoxic heart Lipotoxicity, or glucolipotoxicity, is the result of severe metabolic dysregulation in the face of excess substrate supply and impaired substrate oxidation. (70) (71) In contrast to hibernating myocardium, the metabolic changes are maladaptive and reversible only with the restoration of a normal metabolic milieu. (72) Consequences of dysregulated oxidative metabolism of glucose and fatty acids are the accumulation of glycosylated proteins, triglycerides, reactive oxygen species, diacyl-glycerol and ceramide, among others. (73) Dysregulated fatty acid metabolism provides a rich source of metabolic signals, some of which are regulators of gene expression by binding to specific transcription factors.

In failing human heart muscle there is a high percentage of triglyceride accumulation. Triglyceride levels are highest in obese patients and in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Triglycerides in cardiomyocytes, or “ectopic fat”, are considered markers other than mediators of lipotoxicity. (74) The advent of magnetic resonance imaging is providing an opportunity to image intramyocardial triglycerides in vivo. (75) The same group of investigators found that increased myocardial triglyceride content was accompanied by increased ventricular mass and decreased septal thickening. (76) There is also good evidence for ectopic triglyceride accumulation in the interventricular septum of patients with type 2 diabetes or the metabolic syndrome. (77) Myocardial steatosis has been associated with impaired left ventricular function in patients with uncomplicated type 2 diabetes. (78) Myocardial triglyceride accumulation can be reversed with either exercise or pharmacological intervention.

Myocardial H-MRS to study triglyceride content is a promising new tool to assess the effects of nutritional interventions on myocardial lipid metabolism in relation to heart function. (79) The in vivo assessment of myocardial triglyceride content and turnover has already provided new insights into the pathophysiology of the heart in obesity and diabetes. (77, 80)

Conclusions

Based on the principles of cardiac metabolism we have reviewed the biochemical basis for the various imaging modalities available to track the footprints of normal and deranged metabolic activity in the heart. Akin to flow imaging with radionuclide tracers, a strength of metabolic imaging rests in the assessment of regional myocardial differences in metabolic activity, probing for one substrate at a time. A strong case has been made for the utility of metabolic imaging in the detection of viable yet dysfunctional myocardium which could benefit from reperfusion. At the same time we have still much to learn about the molecular basis of metabolic derangements in all forms of heart disease. The in vivo metabolic imaging of regenerative processes, including remodeling of the heart muscle through controlled protein synthesis and degradation, is still beyond the scope of current imaging modalities. However, it is our hope that new and developing methods of cardiac imaging will lead to an earlier detection of heart disease and improve the management and quality of life of patients afflicted with ischemic and non-ischemic heart muscle disorders.

Acknowledgements

I thank Romain Harmancey for critical comments, and Roxy A. Tate for her expert editorial assistance. Work in my laboratory is supported by the NHLBI and the American Heart Association.

Literature Cited

- 1.Winterstein H. Ueber die Sauerstoffatmung des isolierten Saeugetierherzens. Z Allg Physiol. 1904;4:339–359. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taegtmeyer H. Myocardial energetics: Still only the tip of an iceberg. Heart Lung Circ. 2003;12:3–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-2892.2003.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taegtmeyer H, Golfman L, Sharma S, Razeghi P, van Arsdall M. Linking gene expression to function: metabolic flexibility in the normal and diseased heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:202–213. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taegtmeyer H. Energy metabolism of the heart: from basic concepts to clinical applications. Curr Prob Cardiol. 1994;19:57–116. doi: 10.1016/0146-2806(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes FL. Between Biology and Medicine: The Formation of Intermediary Metabolism. Berkeley, CA: University of California at Berkeley; 1992. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taegtmeyer H, Hems R, Krebs HA. Utilization of energy-providing substrates in the isolated working rat heart. Biochem J. 1980;186:701–711. doi: 10.1042/bj1860701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz AM. Molecular biology in cardiology, a paradigmatic shift. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1988;20:355–366. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(88)80069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taegtmeyer H, Willerson JT, Cohn JN, Wellens HJJ, Holmes DR, editors. Cardiovascular Medicine. 3rd ed. London: Springer-Verlag (London) Ltd.; 2007. Fueling the Heart:Multiple Roles for Cardiac Metabolism; pp. 1157–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrero P, Peterson LR, McGill JB, et al. Increased myocardial fatty acid metabolism in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson LR, Herrero P, Schechtman KB, et al. Effect of obesity and insulin resistance on myocardial substrate metabolism and efficiency in young women. Circulation. 2004;109:2191–2196. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127959.28627.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balaban RS. Cardiac energy metabolism homeostasis: role of cytosolic calcium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1259–1271. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldwin JE, Krebs HA. The evolution of metabolic cycles. Nature. 1981;291:381–382. doi: 10.1038/291381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taegtmeyer H. Carbohydrate interconversions and energy production. Circulation. 1985;72:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bing RJ, Siegel A, Ungar I, Gilbert M. Metabolism of the human heart. II. Studies on fat, ketone and amino acid metabolism. Am J Med. 1954;16:504–515. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1963;1:785–789. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)91500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hue L, Taegtmeyer H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E578–E591. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00093.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Bilsen M, Van der Vusse GJ, Reneman RS. Transcriptional regulation of metabolic processes: implications for cardiac metabolism. Pflugers Arch. 1998;437:2–14. doi: 10.1007/s004240050739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arany Z, He H, Lin J, et al. Transcriptional coactivator PGC-1 alpha controls the energy state and contractile function of cardiac muscle. Cell Metab. 2005;1:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehman JJ, Boudina S, Banke NH, et al. The transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha is essential for maximal and efficient cardiac mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and lipid homeostasis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H185–H196. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00081.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehman JJ, Barger PM, Kovacs A, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:847–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finck BN, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) regulatory cascade in cardiac physiology and disease. Circulation. 2007;115:2540–2548. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.670588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans G. The glycogen content of the rat heart. J Physiol (Lond.) 1934;82:468–480. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1934.sp003198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denton RM, Randle PJ. Concentrations of glycerides and phospholipids in rat heart and gastrocnemius muscles. Biochem J. 1967;104:416–422. doi: 10.1042/bj1040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin GW, Taylor CS, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29530–29539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher DJ, Heymann MA, Rudolph AM. Myocardial oxygen and carbohydrate consumption in fetal lambs in utero and in adult sheep. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:H399–H405. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.3.H399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin GW, Taegtmeyer H. Improved energy homeostasis of the heart in the metabolic state of exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1490–H1501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korvald C, Elvenes OP, Myrmel T. Myocardial substrate metabolism influences left ventricular energetics in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1345–H1351. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bing RJ. The metabolism of the heart. Harvey Lect. 1955;50:27–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1093–1129. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell RR, Taegtmeyer H. Coenzyme A sequestration in rat hearts oxidizing ketone bodies. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:968–973. doi: 10.1172/JCI115679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comte B, Vincent G, Bouchard B, Des Rosiers C. Probing the origin of acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate entering the citric acid cycle from the 13C labeling of citrate released by perfused rat hearts. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26117–26124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibala MJ, Young ME, Taegtmeyer H. Anaplerosis of the citric acid cycle: role in energy metabolism of heart and skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;168:657–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tirosh R, Mishor T, Pinson A. Glucose is essential for the initiation of fatty acid oxidation in ATP-depleted cultured myocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;162:159–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00227544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taegtmeyer H. The failing heart. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2545–2546. author reply 2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wisneski JA, Gertz EW, Neese RA, Gruenke LD, Morris DL, Craig JC. Metabolic fate of extracted glucose in normal human myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1819–1827. doi: 10.1172/JCI112174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gertz EW, Wisneski JA, Stanley WC, Neese RA. Myocardial substrate utilization during exercise in humans. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:2017–2025. doi: 10.1172/JCI113822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGarry JD, Mills SE, Long CS, Foster DW. Observations on the affinity for carnitine and malonyl-CoA sensitivity of carnitine palmitoyl transferase I in animal and human tissues. Demonstration of the presence of malonyl-CoA in non-hepatic tissues of the rat. Biochem J. 1983;214:21–28. doi: 10.1042/bj2140021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ussher JR, Lopaschuk GD. The malonyl CoA axis as a potential target for treating ischaemic heart disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:259–268. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodwin GW, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of fatty acid oxidation of the heart by MCD and ACC during contractile stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E772–E777. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.4.E772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen TM, Goodwin GW, Guthrie PH, Taegtmeyer H. Effects of insulin on glucose uptake by rat hearts during and after coronary flow reduction. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2170–H2177. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.5.H2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen VT, Mossberg KA, Tewson TJ, et al. Temporal analysis of myocardial glucose metabolism by 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H1022–H1031. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, et al. The [14C] deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: Theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;28:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hariharan R, Bray M, Ganim R, Doenst T, Goodwin GW, Taegtmeyer H. Fundamental limitations of [18F]2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose for assessing myocardial glucose uptake. Circulation. 1995;91:2435–2444. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doenst T, Taegtmeyer H. Profound underestimation of glucose uptake by [18F]2-deoxy-2-fluoroglucose in reperfused rat heart muscle. Circulation. 1998;97:2454–2462. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.24.2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bøtker HE, Goodwin GW, Holden JE, Doenst T, Gjedde A, Taegtmeyer H. Myocardial glucose uptake measured with fluorodeoxyglucose: A proposed method to account for variable lumped constants. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1186–1196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeGrado TR, Wang S, Holden JE, Nickles RJ, Taylor M, Stone CK. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of (18)F-labeled 4-thia palmitate as a PET tracer of myocardial fatty acid oxidation. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dence CS, Herrero P, Schwarz SW, Mach RH, Gropler RJ, Welch MJ. Imaging myocardium enzymatic pathways with carbon-11 radiotracers. Methods Enzymol. 2004;385:286–315. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)85016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knuuti M, Nuutila P, Ruotsalainen U, et al. Euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp and oral glucose load in stimulating myocardial glucose utilization during positron-emission tomography. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1255–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knuuti MJ, Yki-Jarvinen H, Voipio-Pulkki LM, et al. Enhancement of myocardial [fluorine-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by a nicotinic acid derivative. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:989–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Opie L. The Heart. Physiology, from Cell to Circulation. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven Publishers; 1998. Fuels: Aerobic and Anaerobic Metabolism; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Depre C, Vanoverschelde JL, Melin JA, et al. Structural and metabolic correlates of the reversibility of chronic left ventricular ischemic dysfunction in humans. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1265–H1275. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanoverschelde JL, Wijns W, Borgers M, et al. Chronic myocardial hibernation in humans. From bedside to bench. Circulation. 1997;95:1961–1971. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Camici PG, Wijns W, Borgers M, et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic reversible left ventricular dysfunction due to coronary artery disease (hibernating myocardium) Circulation. 1997;96:3205–3214. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luisi AJ, Jr, Suzuki G, Dekemp R, et al. Regional 11C-hydroxyephedrine retention in hibernating myocardium: chronic inhomogeneity of sympathetic innervation in the absence of infarction. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1368–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berry JJ, Baker JA, Pieper KS, Hanson MW, Hoffman JM, Coleman RE. The effect of metabolic milieu on cardiac PET imaging using fluorine-18-deoxyglucose and nitrogen-13-ammonia in normal volunteers. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:1518–1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zimmermann R, Tillmans H, Knopp WH. Regional myocardial 13N-glutamate uptake in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:549–556. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)91530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: A method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–E223. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knuuti J. PET imaging of heart and skeletal muscle: An overview. Cardiovasc Mol Imag. 2007;31:319–324. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stone CK, Holden JE, Stanley W, Perlman SB. Effect of nicotinic acid on exogenous myocardial glucose utilization. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:996–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Depre C, Vatner SF. Mechanisms of cell survival in myocardial hibernation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gropler R, Taegtmeyer H. Multiple roles of cardiac metabolism: New opportunities for imaging the phsyiology of the heart. Cardiovasc Mol Imag. 2007;30:309–316. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Opie LH, Sack MN. Metabolic plasticity and the promotion of cardiac protection in ischemia and ischemic preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1077–1089. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taegtmeyer H, Dilsizian V. Imaging myocardial metabolism and ischemic memory. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5(Suppl 2):S42–S48. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Rooij E, Marshall WS, Olson EN. Toward microRNA-based therapeutics for heart disease: the sense in antisense. Circ Res. 2008;103:919–928. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.183426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rajabi M, Kassiotis C, Razeghi P, Taegtmeyer H. Return to the fetal gene program protects the stressed heart: a strong hypothesis. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12:331–343. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mäki M, Luotolahti M, Nuutila P, et al. Glucose uptake in the chronically dysfunctional but viable myocardium. Circulation. 1996;93:1658–1666. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.9.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Depre C, Vanoverschelde JL, Gerber B, Borgers M, Melin JA, Dion R. Correlation of functional recovery with myocardial blood flow, glucose uptake, and morphologic features in patients with chronic left ventricular ischemic dysfunction undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;113:82–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70335-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Depre C, Taegtmeyer H. Metabolic aspects of programmed cell survival and cell death in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:538–548. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00266-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Young ME, Guthrie PH, Razeghi P, et al. Impaired long-chain fatty acid oxidation and contractile dysfunction in the obese Zucker rat heart. Diabetes. 2002;51:2587–2595. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharma S, Adrogue JV, Golfman L, et al. Intramyocardial lipid accumulation in the failing human heart resembles the lipotoxic rat heart. Faseb J. 2004;18:1692–1700. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2263com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Golfman LS, Wilson CR, Sharma S, et al. Activation of PPARgamma enhances myocardial glucose oxidation and improves contractile function in isolated working hearts of ZDF rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E328–E336. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00055.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harmancey R, Wilson CR, Taegtmeyer H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in obesity. Hypertension. 2008;52:181–187. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.110031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brookheart RT, Michel CI, Schaffer JE. As a matter of fat. Cell Metab. 2009;10:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Szczepaniak LS, Babcock EE, Schick F, et al. Measurement of intracellular triglyceride stores by H spectroscopy: validation in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E977–E989. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins RL, Metzger GJ, et al. Myocardial triglycerides and systolic function in humans: in vivo evaluation by localized proton spectroscopy and cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:417–423. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McGavock JM, Lingvay I, Zib I, et al. Cardiac steatosis in diabetes mellitus: a 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation. 2007;116:1170–1175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.645614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rijzewijk LJ, van der Meer RW, Smit JW, et al. Myocardial steatosis is an independent predictor of diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1793–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lamb HJ, Smit JW, van der Meer RW, et al. Metabolic MRI of myocardial and hepatic triglyceride content in response to nutritional interventions. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:573–579. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32830a98e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szczepaniak LS, Victor RG, Orci L, Unger RH. Forgotten but not gone: the rediscovery of fatty heart, the most common unrecognized disease in America. Circ Res. 2007;101:759–767. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]