Abstract

Although most care to frail elders is provided informally, much of this care is paired with formal care services. Yet, common approaches to conceptualizing the formal–informal intersection often are static, do not consider self-care, and typically do not account for multi-level influences. In response, we introduce the “convoy of care” model as an alternative way to conceptualize the intersection and to theorize connections between care convoy properties and caregiver and recipient outcomes. The model draws on Kahn and Antonucci's (1980) convoy model of social relations, expanding it to include both formal and informal care providers and also incorporates theoretical and conceptual threads from life course, feminist gerontology, social ecology, and symbolic interactionist perspectives. This article synthesizes theoretical and empirical knowledge and demonstrates the convoy of care model in an increasingly popular long-term care setting, assisted living. We conceptualize care convoys as dynamic, evolving, person- and family-specific, and influenced by a host of multi-level factors. Care convoys have implications for older adults’ quality of care and ability to age in place, for job satisfaction and retention among formal caregivers, and for informal caregiver burden. The model moves beyond existing conceptual work to provide a comprehensive, multi-level, multi-factor framework that can be used to inform future research, including research in other care settings, and to spark further theoretical development.

Keywords: Formal care, Informal care, Long-term care, Theory, Assisted living

Introduction

Presently, as was true in the past, most care for frail older adults in the United States is provided informally by family and friends at home (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2009). Yet, increasing longevity, changing family structures (i.e., the rise of divorce and single-parent households, delayed child bearing, decreasing family size) and gender expectations, including women's increasing labor force participation, mean a growing number of elders require and will use formal long-term care (LTC) services, including home care, nursing homes, and a rapidly growing segment of the industry, assisted living (AL). The National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP's (2009) recent survey on informal caregiving suggests that nearly 43.5 million people in the United States provide informal care to someone 50 years of age and older, and many do so with formal support in the home or other LTC environments.

Over the years gerontologists have highlighted the need to understand the relationship between formal and informal care as it pertains to supporting frail elders in the United States and elsewhere (Litwin & Attias-Donfut, 2009; Lyons & Zarit, 1999; McAuley, Travis, & Safewright, 1990; Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003). Researchers have investigated formal–informal care intersections in home care (e.g., Ayalon, 2009; Ball & Whittington, 1995; Martin-Matthews, 2007; Neysmith & Aronson, 1997; Parks, 2003; Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003), nursing homes (e.g., Gladstone & Wexler, 2002a, 2002b; Shield, 2003), and, to a lesser extent, AL settings (Ball et al., 2005). Yet existing work does not offer a comprehensive understanding of the intersection of formal and informal care, including the factors that influence its interface and ensuing outcomes for care recipients and their caregivers. This knowledge gap is related in large part to limited theoretical development. Developing more advanced understandings of the formal–informal care relationship has important implications for improving the well-being, quality of life, quality of care, and satisfaction of those who give and receive paid and unpaid care, including the increasing numbers who are projected to do so in the future.

In this article we consider common approaches to understanding the formal–informal care intersection, and, responding to the strengths and shortcomings of existing models, propose an alternative approach based on a synthesis of theory and empirical data. The main tenets of this proposed approach are applicable across care settings. However, we illustrate the approach in the AL context and draw on existing empirical research, including, but not limited, to our own.

Existing conceptual models

Research interest in the formal–informal care intersection goes back decades, but, as suggested, remains theoretically underdeveloped. Scholarly observers (see for example, Connidis, 2010; Litwin & Attias-Donfut, 2009; Lyons & Zarit, 1999) identify several conceptual models that dominate the literature and are considered “conventional” (Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003, p. 191). First, Cantor's (1979, 1991) hierarchical compensatory model suggests a preferred ordering of caregivers based on social relationships, with those who are closer to the care recipients, usually kin, being the most preferred and formal care workers the least. Among kin, spouses are at the top of the hierarchy, followed by children, other family members, and friends. Next, the substitution model (see Greene, 1983) hypothesizes that once formal care is introduced it replaces informal care. Thus, little interface exists between the two sources as informal caregivers are understood to use formal care to substitute for their care. Third, the task specificity model put forth by Litwak (1985) suggests that the care task dictates the caregiver type, with more skilled care being performed by formal, trained caregivers, and formal and informal care complement one another. Finally, the complementary model (see Chappell & Blandford, 1991) hypothesizes that formal care can both compensate for and supplement informal care; in this case formal care supplements informal care based on the older adult's escalating care needs.

In their examination of home care and the interface between nurses and family caregivers in Canada, Ward-Griffin and Marshall (2003) critiqued these conceptual models using a socialist-feminist lens. They note that the models treat formal and informal care as two separate, rather than potentially overlapping, spheres and privilege normative assumptions of family care as preferred and natural. Their empirical work involving nurses from community nursing agencies and family caregivers of elderly relatives demonstrates how skilled care work often is transferred from nurses to family members, which suggests a blurring of boundaries between formal and informal domains. Highlighting the absence of wider political, social, and economic contexts in conventional models, Ward-Griffin and Marshall (2003) identify structural arrangements, such as gender roles, power relations, the feminization of care, reduced state funding for home care, and increasing nurse case loads as keys to understanding formal–informal care intersections.

Conventional models also exclude care recipients as potentially active participants in their own care (i.e., self-care), including their roles in care management and supervision, and do not reflect the dynamic (i.e. evolutionary) nature of care processes or the increasing complex medical care needs of those with chronic disease and disability. Moreover, they do little to account for how different care settings influence formal–informal care intersections. Homes, nursing homes, and AL facilities differ considerably from one another as well as among themselves. Regarding across-setting variation, AL, for example, often is marketed as homelike and ideally facilitates aging in place by maximizing independence and altering support as necessary (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell, et al., 2004; Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Hollingsworth, et al., 2004; Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, 2009). Unlike other formal care settings, AL environments are non-medical and typically do not provide skilled care. AL also was not designed to provide total care (Golant, 2008) and assumes a certain amount of informal care, including self-care and kin work (Ball et al., 2005). Thus, residents and families represent an important source of support and are integral to realizing AL's social (as opposed to medical) model of care (Hyde, Perez, & Reed, 2008). Port et al.'s (2005) LTC research finds that AL residents’ family members experience more burden than those of nursing home residents — a finding that likely reflects greater opportunity and demand for informal care in these settings.

Gaugler and Kane's (2007) synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research on family involvement in AL concludes by noting the prevalence of “simplistic causal models” (p. 95). Identifying variation across AL settings and families, they suggest the need to account for the influences of facility-level characteristics and family structure. They also note the common use of cross-sectional data despite the “transitional nature of family involvement” (p. 97).

In an earlier synthesis of research on families in nursing homes and AL, Gaugler (2005, p. 113) highlighted the practice of relying on a “primary’ family member” as a conceptual limitation and the challenge of interpreting findings for residents without family. He offers a potential model of family involvement incorporating elements of Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit and Whitlach's (1995) multi-dimensional stress process model. Gaugler suggests that the pre-placement caregiving situation and post-placement facility, resident, staff, and family factors join to influence family involvement in formal care settings, all of which have outcomes for family members (psychosocial adaption and care satisfaction), residents (quality of life and health outcomes), staff (job satisfaction and quality of care provided), and facilities (family-orientation). This model addresses many shortcomings of existing work but does not account for broader social and life course influences, non-kin caregivers, or self-care, and its intended focus is family involvement rather than care collaboration. Thus, while this and other models offer guidance, additional theoretical work and an alternative approach are needed in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of formal–informal care relationships.

An alternative approach

Care collaborations are best conceptualized as dynamic and evolving processes that are person- and family-specific, negotiated, and influenced by a host of multi-level factors encompassing societal, community, facility and individual levels. Borrowing from existing theoretical and conceptual frameworks, empirical data suggest that alongside threads from life course (Elder, 1998), feminist gerontology (Calasanti, 2009; Calasanti & Zajicek, 1993), social ecological (Moos, 1979), and symbolic interactionist (Blumer, 1969) perspectives, elements of Kahn and Antonucci's (1980) “convoy model of social relations” hold considerable promise for theorizing in this area. In what follows we present the “convoy of care model” as an alternative way of conceptualizing the intersections between formal and informal care and of theorizing its relationship to care recipient and caregiver outcomes. Beginning with the convoy model of social relations, we first discuss the key conceptual and theoretical threads (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Theoretical threads and contributions to convoy of care model by perspective.

| Convoy model of social relations (Antonucci, 1985; Antonucci et al., 2009; Kahn & Antonucci, 1980) | Life course perspective (Elder, 1998; Elder & Clipp, 1988) | Feminist gerontology and socialist feminist thought (Calasanti, 2009; Calasanti & Slevin, 2001; Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003; Young, 1990) | Social ecological perspective (Moos, 1979) | Symbolic interactionist perspective (Blumer, 1969; Finch, 1989; Finch & Mason, 1993, see also Strauss et al., 1963) |

| Takes an evolutionary or longitudinal view of social (informal) support. | Aging is a lifelong process. Life course studies require longitudinal approaches. | Identifies an interlocking structure of social hierarchies, intersecting inequalities, and power relations. | Assumes that individuals cannot be divorced from their environments and surrounding contexts, including others around them and must be studied together. | Emphasizes meaning, interpretation, and lived experience. Negotiation is a key feature of social, organizational and family life, and caregiving, and requires a longer view. |

| Individuals are embedded in convoys (i.e., collection of close social relationships). | Focuses on “linked lives” (i.e., that lives are lived interdependently). | Relations of inequality are largely based on gender, race, ethnicity, age, health, sexuality, and class-based positions. They arise through social interaction and reflect structural arrangements. | Aims to understand the experience of the environment from the individual's perspective | Individuals negotiate their “own course of action” yet, outcomes are not open-ended and often “tightly constrained” (Finch & Mason, 1993:60). |

| Convoy members give, receive, and exchange support. Convoys generally serve a protective function and provide support in the form of: aide, emotional support, and affirmation. | Life course changes are conceptualized as transitions (change in state) and turning points (change in direction) and often affect more than the individual and those surrounding them. | Oppressed groups experience marginalization, lack of authority, and powerlessness. | Emphasis is placed on adjustment and adaptation. | Care negotiations are an outcome of the interplay between structure and agency. “Legitimate excuses” (Finch, 1989) exist; certain situations are socially acceptable reasons for not upholding what normally would be perceived as a family responsibility and often vary by gender. |

| Convoy properties are measured by: structure, function, and adequacy. | Life course trajectories are influenced by: human agency that varies in constraints andoptions, the importance of location in time and place, and the timing of life events. | Demonstrates paid and unpaid caregiving as devalued and the ideology of familism as influencing the pervasive belief that care is the domain of families and women. In studying care, emphasize is placed on “relational autonomy” to show interdependence between care recipients and their paid and unpaid caregivers (Parks, 2003:85–86). | Implies the need to study context in-depth and at multiple levels. In understanding health behaviors and outcomes, for example, the perspective posits that processes operate at multiple, intersecting levels ofsocial life (e.g., society, community, organizational, networks and relationships, and individual). | |

| Convoys are influenced by personal and situational characteristics. | These aforementioned factors join to create different life course trajectories. | |||

| Convoys influence individuals’ health and well-being. | Social identities and positions are at stake in negotiations; issues of power and control are intertwined with negotiation and the balance of dependence and interdependence (Finch & Mason, 1993:58). | |||

“Convoys of care”: conceptual and theoretical threads

As a theoretical and methodological approach, the convoy model of social relations has roots in anthropology (Plath, 1980) and psychology (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). It offers a theoretical foundation for elucidating the relationship between social relations, health, and well-being (Antonucci, Birditt, & Akiyama, 2009). The model takes an evolutionary view of informal social support and posits that individuals are embedded in convoys, which are dynamic networks of close personal relationships that serve as “vehicles through which social support is distributed or exchanged” (Antonucci, 1985, p. 96). The life course principles of “linked lives”, or the notion that lives are lived interdependently, and the importance of taking a longer view of social relationships (Elder, 1998) are implicit in the convoy metaphor, which is used to capture the changes in convoy membership and support exchanges over time (Kahn, 1979).

Generally, though not universally, relationships with convoy members serve a protective function and provide support in the form of assistance, including instrumental care, emotional support, and affirmation (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). Family members, including from multiple generations, often are convoy members (Antonucci, Birditt, Sherman, & Trinh, 2011). As individuals move through the life course, convoy members may be lost and gained, often in conjunction with life course transitions such as family- and health-related change (Antonucci, 1985). Research on intergenerational family life finds that the nature and amount of informal support given or received within families can change over time in response to needs and abilities (Connidis & Kemp, 2008), ebbing, flowing, and sometimes involving “turn taking” among members (Richlin-Klonsky & Bengston, 1996, p. 274).

Convoy properties include structure (e.g., size, homogeneity, stability), function (i.e., support given, received, exchanged), and adequacy (i.e., satisfaction with support) and are influenced by personal and situational characteristics (Antonucci, 1985; Antonucci et al., 2011). Personal characteristics refer to individuals’ social, demographic, health, and other individual characteristics, such as gender, age, race and ethnicity, social class, marital status, sexual orientation, frailty, and personality. Situational characteristics are external to the individual and “aspects of the environment”, including for example role expectations, norms, and living situation (Antonucci, 1985, p. 100).

Adding threads from other theoretical perspectives further highlights the importance and intersection of contextual factors and directs analytic gaze to the relationship between individuals and society. Life course (Elder, 1998; Elder & Clipp, 1988) and symbolic interactionist (Blumer, 1969) perspectives suggest individuals have agency and make choices but do so within the opportunities and constraints of their lives, including their relationships with others, previous choices, and their location in historical time, place, and social structure. Feminist gerontology draws specific attention to the structural arrangements that shape individuals’ lives and enhance or limit agency (Calasanti & Zajicek, 1993). Gender relations are emphasized, but theorists also point to intersecting inequalities based also on race, ethnicity, age, sexuality, and social-class position (Calasanti, 2009). One's position in the social structure affects resources and power such that oppressed groups are faced with economic marginalization, lack of authority, and powerlessness (Young, 1990).

Feminist theorizing identifies familism as a pervasive ideology that defines care as a family responsibility and, ultimately, women's work (Aronson, 1990; Aronson & Neysmith, 1997). Consequently, paid and unpaid care is devalued and marginalized, often rendered invisible (Parks, 2003). Calling for an “ethic of care”, Parks (2003:87) emphasizes “relational autonomy” in her critique of the treatment and status of home care workers in the United States. She argues that those involved in the caregiving process, including care recipients and their paid and unpaid caregivers, are connected in ways that are consequential to one another's selves and well-being and that all are affected by the political and economic frameworks in which they are embedded (Parks, 2003: 85–86; see also Holstein, 1999; Holstein, Parks, & Waymack, 2011; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012). Calasanti and Slevin (2001, p. 143) also identify ageist assumptions regarding dependence in later life and argue that older adults being cared for are not necessarily “passive care recipients.”

The foundation of a social ecology framework, which often is applied to health behaviors and outcomes, also suggests that individuals cannot be divorced from their surrounding environments (Moos, 1979). Adding elements of this framework to the convoy model further highlights the importance of multiple, intersecting, nested contexts, including societal-, community-, institutional-, and individual-level factors. Meanwhile, adding tenets of symbolic interactionist thought draws analytic import to meaning and interpretation as central to action and interaction (Blumer, 1969). From this perspective, care is a process that is “negotiated” or worked out over time (Finch & Mason, 1993) among convoy members. Strauss, Schatzman, Erlich, Bucher and Sabshin's (1963) seminal work in hospital settings introduces the concept of “negotiated order”, which involves interactions among and between various actors in different roles and positions. Structural conditions influence negotiations, which evolve and require renegotiation over time, shaping how care is organized (Strauss et al., 1963).

In both formal and informal care situations, social identities and positions often are at stake in negotiations. Finch and Mason's (1993, p. 58) work on family responsibility, for example, suggests that “issues of power and control are closely intertwined with the negotiation of the balance between dependence and interdependence” when family members work out support arrangements. In families, negotiating who is responsible for what often depends on whether one has “legitimate excuses” (i.e., socially acceptable situations for failing to accept/perform what ordinarily would be viewed as a family responsibility) (Finch, 1989). Negotiation takes place within the contexts of previous negotiations, structural arrangements, and normative and personal expectations (Finch, 1989; Finch & Mason, 1993; Gubrium, 1988). Longitudinal research on multi-generational families suggests that they have “caregiving systems” that provide frameworks for how care is viewed and exchanged among members and influence formal–informal support patterns (Pyke & Bengston, 1996). Such systems are akin to Strauss et al.'s (1963) “negotiated order.”

Expanded, modified, and applied to the care process, the “convoy” metaphor suggests an evolutionary collaboration of care partners involving both formal and informal caregivers and their care recipients. Thus, convoys of care are the evolving collection of individuals who may or may not have close personal connections to the recipient or to one another, but who provide care, including help with activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), socio-emotional care, skilled health care, monitoring, and advocacy. Each individual's care convoy has properties unique in structure and function, both of which can influence its adequacy. As illustrated below, who does what in individual care convoys generally changes over time through negotiation. Care convoys and negotiations are influenced by factors at the societal, community, care industry, care setting, formal–informal network, and individual levels. We posit that care convoys have outcomes for self and identity, which are intimately connected to care recipients’ ability to age in place and well-being, as well as for informal caregivers’ sense of fulfilling family responsibility (see for example, Pinquart & Sorensen, 2005), satisfaction with care, and levels of care burden and formal care workers’ job satisfaction.

Supporting data

In order to illustrate the convoy of care model, we draw on existing AL research, including but not limited to, three recent studies conducted in Georgia in AL settings varying in size, location, ownership, and resident characteristics. We integrate findings from previously published analyses in AL, including our own, and where appropriate also draw on our unpublished data to further illustrate the model, its components, and potential outcomes. Table 2 outlines select characteristics of the three studies. Study 1 (S1) was a statewide mixed-methods, multi-level study, which aimed to learn how to create work environments that maximize satisfaction and retention among direct care workers (DCWs). Study 2 (S2) used demographic and qualitative interviews to explore the phenomenon of married couples’ living together in AL. Study 3 (S3) employed mixed methods to examine the negotiation of residents’ social relationships, including the structure, function, and adequacy of support and the factors that influence support. It was informed by Kahn and Antonucci's (1980) conceptual and methodological framework and used Antonucci's (1986) hierarchical social network mapping technique. Detailed information about these studies, including data collection and analysis techniques, and ethical considerations, are published elsewhere (see Table 2). All three studies received IRB approval from Georgia State University.

Table 2.

Select study characteristics by study.

| Study/characteristic | Study 1 (S1) Satisfaction and retention of care staff in AL | Study 2 (S2) Married couples in AL | Study 3 (S3) Negotiating residents’ social relationships in AL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Funding dates | 2004–2008 | 2005–2007 | 2008–2011 |

| Number of AL settings | 45 | 131 (demographic interview sites) 11 (interview sites) |

8 (mixed methods) 1 (surveys only) |

| Number of counties | 28 | 10 | 3 |

| AL resident licensing capacity range | 16–160 beds | 28–80 beds | 18–100 beds |

| Location(s) | Statewide (Georgia) | 10-county area around Atlanta, GA | 4 counties around Atlanta, GA |

| Monthly fee range | $544–$6595 | $2800–$5500 | $2100–$5295 |

| Participants /methods | |||

| Surveys (includes closed-and open-ended questions) | Care staff (n = 370) | Administrators (n= 131) | Residents (n=207) |

| Formal in-depth qualitative interviews | Administrators (n=43) Care staff (n=41) |

Married couples (n = 20) Adult children (n = 10) |

Administrators (n = 8) Residents (n = 44) |

| Care staff(n = 13) | |||

| Activitystaff(n = 7) | |||

| Participant observation | 659 h | Limited | 3264 h |

| Published materials | Baird, Adelman, Sweatman, Perkins, Ball, & Liu (2010), Ball, Hollingsworth, & Lepore, (2010), Ball & Perkins (2010), Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Kemp, (2010), Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Lepore (2010), Kemp, Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Lepore (2009), Lepore, Ball, Perkins, & Kemp (2010), and Perkins, Adelman, Furlow, Sweatman, & Baird (2010) | Kemp (2008, 2012) | Kemp et al. (2012) and Perkins, Ball, Kemp, et al. (2012) |

Convoys of care in assisted living

Empirical evidence suggests that although support members (e.g. neighbors) may be lost with the transition to AL, residents arrive with preexisting care convoys and most have members who continue involvement (Ball et al., 2005). Viewed through a life course lens, the move to AL can be seen as a transition for older adults and informal caregivers, who are apt to experience a shift in their “caregiver career” (Aneshensel et al., 1995) rather than an abrupt end (Ball et al., 2005; Kemp, 2012; Williams, Zimmerman, & Williams, 2012; Wolf & Jenkins, 2008). AL expands residents’ care convoys to include AL care workers and potentially other residents, their families, volunteers, and formal caregivers from outside the AL setting (Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Perkins, 2012; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2012). Our analysis of residents’ social support networks in S3 indicate they are variable, yet nearly all residents (99%) included family in their networks; 29% identified other residents, and AL staff and friends outside the setting also were identified as network members (Kemp et al., 2012; Perkins, Ball, Kemp, et al., 2012). Quantitative analysis of the influence of network composition on resident well-being further suggests that possessing a greater proportion of family member in one's network is the most important predictor of well-being, but having some ties to co-residents and non-family members outside AL also positively influences well-being a finding also supported by qualitative data (Perkins, Ball, Kemp, et al., 2012). Care convoy structure also influences care processes and outcomes.

Influential factors

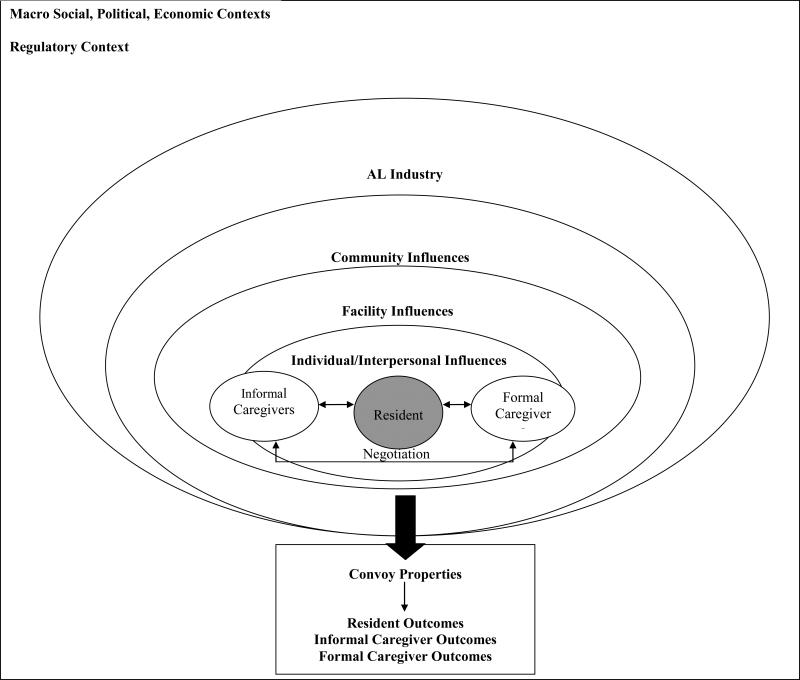

Convoys are nested in and influenced by factors at multiple levels beginning with broader social, economic, and political forces (see Fig. 1). These influences shape the labor market, the balance between formal and informal care, social policy (e.g., Family Medical Leave Act), and the AL industry, ultimately affecting who gives and receives care and under what circumstances. AL is state-regulated and varies widely across the nation in terms of precise name, definition, and regulation. In general, however, these settings do not provide skilled nursing care, and most are private pay (Golant, 2008). Nationwide, more than one million individuals live in AL (Golant, 2008). The typical resident is White, female, and over the age of 87 (National Center for Assisted Living, 2009), and most are without a spouse (Centers for Disease Control, 2010; Kemp, 2008). DCWs in these settings are overwhelmingly female, often non-White, and increasingly foreign-born (Ball & Perkins, 2010).

Fig. 1.

The convoy of care model.

The majority of DCWs have dependents, are unmarried, and have low levels of formal education (the majority with high school education or less) and minimal or even no LTC experience or training, and their work is low-paying and physically and emotionally demanding (Ball & Perkins, 2010; Ball, Perkins, et al., 2010). The industry suffers from retention problems and high turnover rates (Stone, 2010). In S1, 42% of DCWs left their jobs within a year of being interviewed (Perkins et al., 2010). Such high DCW turnover prompts considerable change in residents’ care convoys.

Recent economic factors have caused elders to delay AL moves and can motivate facilities to retain residents for as long as possible to survive in a competitive market (Carder, Morgan, & Eckert, 2008; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, et al., 2012; Polivka, 2010). Consequently, AL residents have become older and frailer, with many resembling nursing home residents (Polivka, 2010). Given the industry's emphasis on “home-like” environments, it is not surprising that most residents prefer to age (i.e., die) in place, rather than move to the more institutional nursing home environment, and recent estimates suggest that between 14 and 22% of residents die in AL each year in the United States (Golant, 2004; Munn, Hanson, Zimmerman, Sloane, & Mitchell, 2006; Zimmerman et al., 2005), including nearly half in dementia care units (Hyde et al., 2008). These patterns are accompanied by growth in the use of hospice (Cartwright, Miller, & Volpin, 2009), home health, physical and occupational therapy, and private sitters (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell, et al., 2004). In all three studies outlined in Table 2, external formal care was a common strategy to reduce the care burden of families and AL staff and facilitate resident retention. Aging in place is supported also by changes in AL regulations in some states (Mollica, 2005), including Georgia where recent legislation opens the door for homes with 25 or more beds to serve residents with a higher level of impairment than was possible in the past and allows nurse delegation. Without doubt, the landscape of care is becoming increasingly complex and requires consideration when studying care convoys.

Ongoing social and demographic changes also are transforming families and family life, and affecting the structure of convoys; increasing longevity and shifting patterns of marriage, divorce, remarriage, childlessness and so forth shape who is available to provide informal support (Antonucci et al., 2011). As in other care settings, our recent AL research indicates that older adults’ care convoys can include nieces and nephews, in-laws, step-ties, and fictive kin or friends alongside or in place of children, spouses, or siblings (see also Ball et al., 2005).

Community factors such as size, location, population density, economy, and social resources are influential to care arrangements, including who is involved in care and the ratio of formal to informal care (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell, et al., 2004). These factors shape the range and quality of formal services available to AL residents. For instance, access to hospice and other health care services varies by location with rural and poor areas having the least access (Last Acts, 2002).

Community factors also include local job markets, which influence paid care workers’ education, training, job opportunities, and wages, affecting who applies and is hired to care in AL (Ball, Hollingsworth, et al., 2010). Involvement of individuals and organizations in a given home influences residents’ support networks (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, et al., 2012). For example, volunteers, including those from local churches, synagogues, and schools, can be important care convoy members in homes with strong community connections (S3). In smaller towns, especially rural settings, more homogeneity and preexisting ties between staff, families, and residents are more likely than in larger, urban settings and influence care relations (Kemp et al., 2009, 2010; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, et al., 2012).

Facility factors likewise influence convoys and include size, location (overlapping with community), resources, ownership, staffing levels, worker training, job configuration, and turnover rates, and resident admission and retention policies. Smaller homes frequently are described as “home” or “family-like” by staff, residents, and family members and generally promote greater familiarity among these groups (Ball et al., 2005; Kemp et al., 2010). Small homes often are owner-run, located in poor communities, serve minority and low-income residents, and have fewer resources, including fewer qualified staff and less family support (Ball et al., 2005; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Combs, 2004; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, et al., 2012). A DCW from one such home noted, “We don't have too many families come in. They just bring them and they come once a month; they bring their check and that's it” (S1). In some homes administrators endeavor to create connections between staff, residents, and families through social events, meetings, and open communication (Kemp et al., 2009, 2010, 2012). One administrator from S1 elaborated, “The more the family is educated, the more they will realize what the care staff can and cannot do. Unless there is open communication then they don't know.” Another explained a practice in her large, corporately-owned home: “We do quarterly reassessments and I always call the family after that's been done and let them know if anything has changed about the care requirements of their family member.” Yet, such practices are not universal.

Staffing levels and job configuration influence the number of DCWs and the time they are able to spend on care tasks (Ball, Hollingsworth, et al., 2010). Along with worker training, these factors also can influence care quality and interactions among caregivers and between caregivers and recipients (Ball, Lepore, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Sweatman, 2009; Kemp et al., 2010). Certain administrators in S1 prohibited DCWs from communicating with families about resident care while others, “let them talk freely” because they “trust and train” (see also, Kemp et al., 2009). The level of team work in a given home affects co-worker relationships (Perkins, Sweatman, & Hollingsworth, 2010) and is apt to influence care delivery.

In certain settings administrators rotate staff while in others they are assigned specific residents; these practices affect convoy size, distribution of care burden, and familiarity among care partners (Kemp et al., 2010). One S1 administrator explained her preference: “If we are switching too much it will not allow us to be as consistent as we want. But we will do what we have to [to] make sure that the residents are comfortable, and to make the staff comfortable.” Staffing changes and turnover rates similarly affect care collaborations. A daughter from S2 noted of her parents’ corporately owned residence, “They like to promote within the ranks and relocate them in different jobs pretty frequently. It's frustrating from a family member's and from the resident's standpoint because you're not quite sure what you're going to be dealing with next.”

Admission and retention policies affect resident characteristics and the types and amount of care needed (Ball, Hollingsworth, et al., 2010). Caring for frailer residents requires greater resources, including increased staffing levels and utilization of external formal care, yet homes without these supports sometimes retain heavier-care residents out of economic necessity (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell, et al., 2004; Ball et al., 2005; Perkins et al., 2004). Consequently, residents’ care convoys and care outcomes are qualitatively different in homes with access to greater support.

Certain formal caregiver factors influence convoys, including personal characteristics, identities, and relationships. Commonality of culture, race, or background among caregivers and with residents often is associated with collaborative care relations (i.e., those which involve effective communication and cooperation between convoy members). Differences sometimes are not. For example, qualitative and quantitative data indicate that racism directed at Black care workers from White families, residents, supervisors and other co-workers is detrimental to care relationships and to job satisfaction and retention among DCWs (Baird, Adelman, Sweatman, Perkins, & Ball, 2010; Ball et al., 2009; Kemp et al., 2010; Perkins, Sweatman, et al., 2010). In some urban homes we also observed conflict between African and American born DCWs regarding perceived work ethics and communication barriers (Perkins, Sweatman, et al., 2010). Position in the social structure and associated power relations can and often do shape micro-level interactions and care negotiations and collaborations between convoy members.

Formal caregivers’ job characteristics, including shift (day or night), tenure, training, position (e.g., shift supervisor, medication technician) and role (e.g., AL DCW or hospice worker) all influence configurations of care and care relationships (Kemp et al., 2010). Among DCWs in larger AL settings, conflicts between shifts frequently occur, which can lead to solidarity and cooperation among shift members (Perkins, Sweatman, et al., 2010). DCWs’ attitudes towards families, residents, older persons, and care work also are important, including their perceptions of care work and its meaning in their lives. The majority of DCWs report that relationships with residents are the reasons they become caregivers and stay in their jobs (Kemp et al., 2010; Lepore et al., 2010). Those who say they “love being needed” often have closer relationships with residents and families (Ball et al., 2009; Kemp et al., 2009, 2010).

Meanwhile, informal caregivers’ relationship and history with the care recipient and other caregivers, perceived sense of responsibility, geographic proximity, the presence or absence of other supporters, life demands, and their own health and material resources influence participation in care. In S2, a son with a history of close relationships with his parents and sister described how they manage daily involvement in their parents’ care, including overseeing medical care, transportation, socio-emotional support, visiting, monitoring, and advocacy:

My sister and I get support from each other. We've got it from our spouses. I've got it at work. I have the Family and Medical Leave Act... I also work for managers who are women who have elderly parents and small children.

Although this sibling pair collaborated daily, they described their third sibling—an out-of-town brother—as being “pretty wrapped up in himself”, “not a great deal of help”, and “a net drain on everyone... when it comes to helping” their parents.

Highly involved family members who are respectful of DCWs are more apt to have closer relationships with them (Kemp et al., 2009). One DCW from S1 noted of families, “The ones that come in here are constantly coming all day long, in and out... you get close to them and they feel comfortable because they know who is here and who is not here, you know taking care of their family members.” Greater family involvement also can translate into greater accountability for residents’ care among DCWs. Yet, some informal caregivers with poor relationship histories are reluctant to participate. For example, another DCW from S2 described a son's involvement saying:

He goes in there and yells at him, and I don't think he should be doing that... I think he gets frustrated at him because he has not seen his daddy since he was like four or five years old. He is in his early fifties and all of this [care] was thrown on him.

As this and the previous quote implies, families vary in how they organize care among themselves to AL residents (Eckert et al., 2009). Ball et al. (2005, p. 152–153), for example, describe “cooperation, conflict, and going solo”, but note that most informal care in AL “is carried out principally by one person who almost always is a child and usually a daughter.”

Residents’ personal characteristics, behaviors, relationships with and treatment of caregivers, material resources, personal preferences, and tenure in the home affect relationships and convoy/network structure, function, and adequacy. A given resident's health conditions and functional status (including social competence) and accompanying care needs also influence convoys. In our studies some residents had very few care needs, while others had more involved care regimens with skilled care needs such as, for example, insulin injections, end-of-life palliative care provided by hospice agencies, physical and occupational therapy, off-site kidney dialysis requiring formal agency- or family-provided transportation, and catheter care provided by home health workers. Family structure and kin availability are consequential. For example married couples in AL tend to have built-in companionship, support, and advocacy (Kemp, 2008, 2012). Meanwhile, residents with children or grandchildren, especially nearby, typically have more consistent support compared to those relying on other kin and those at a distance.

Close, family-like relationships often develop between care staff and residents, blurring formal and informal care boundaries, especially when residents have little or no family support; DCWs sometimes substitute for families by providing emotional support and buying care supplies (Ball et al., 2009; Kemp et al., 2010). Even when families are involved, AL staff typically have greater contact with residents. One administrator from S1 explained, “We are their family. We are the ones they see seven days a week.” When residents express appreciation for DCWs’ care efforts, this behavior promotes closer ties, but rude, disrespectful, or violent residents represented difficult care relationships, which can hinder the care process (Kemp et al., 2010). Data from an interview with a Black DCW in S1, for example, illustrate racist behaviors directed towards her from some White residents and the outcomes:

Mr. B. is very racist. He would not let you do anything for him... he would call us the “n” word. He wouldn't let us bring his tray... There is one more lady... She needed a bulb put in her lamp and she said, “Can you come and put this bulb in for me?” I said, “Yes, ma'am. I will be right there in a second.” So Jane, of course, is White and she said, “Well, that is okay, Jane will do it because I have had so many things taken out of my room” (Kemp et al., 2010, p. 158).

Such experiences further highlight how race relations and perceptions of self and of others can operate to shape care interactions and negotiations.

Negotiation, expectations, preferences, and care roles

Within convoys of care, negotiations between formal and informal care providers and care recipients influence care collaborations. In AL, facility and external DCWs, families, and other informal caregivers often negotiate care among themselves, with other caregiver types, and with residents. Part of negotiation is determining roles, expectations, and preferences, which also are key caregiver and care recipient factors. For most residents, continuing self-care to the degree possible is a key component of quality of life, yet self-care realization often depends on multiple factors, including facility staffing levels, staff training, and adherence to care schedules and standards, family support, and residents’ ability to perform and manage care tasks, as well as their attitudes and values and financial resources (Ball et al., 2000; Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Hollingsworth, et al., 2004; Ball et al., 2005). AL providers typically view their role as taking over ADL care and helping with medications and expect families to “do their part,” generally by providing socio-emotional support and performing a variety of instrumental tasks, such as transportation to medical appointments and shopping for needed items, including care supplies (S1). Family members range considerably in perception and enactment of their care roles and expectations of formal care. One care worker from S1 noted this variation: “Mrs. Reid's daughter will come in and do everything for her. Some of them will not.”

Because care partners do not always agree on care roles or meet others’ expectations, care often must be renegotiated. For example, a 95-year old resident from S1, whose calls for help usually signaled her being “on the floor,” was determined “to do everything for herself” and continually resisted DCW care offers. Meanwhile, a 93-year old resident in S3, resumed control of her medication because she wanted to take her multiple pills at her own pace rather than quickly while a staff member watched and so that she would “know what she is taking.” Conversely some residents need encouragement, including a resident from S2 whose son routinely reminded him, “AL is not total care. AL means you participate.” As in this case, care staff can collaborate with families to encourage self-care. As residents decline, however, care often requires further adjustment and negotiation.

Staff complain when they feel informal caregivers do not do enough (Kemp et al., 2009), and some try to renegotiate for greater family involvement. Alternatively, staff may perceive certain families as over-stepping. A DCW from S1 explained, “I did have a problem with a family member. He was trying to keep up with her medication... It was all screwed up... I stood right up to him [and said] ‘If you want me to take care of your mama, you need to let me do that.’”

Many involved family members perceive their role as having a presence in order to monitor and advocate for high quality care, which involves on-going negotiation. Making a representative statement, a daughter from S3 noted, “As the child of a resident, being there frequently makes a huge difference... it concerns me about people that [do] not have that same interested party following up their care.” One of her out-of-town brothers participates at a distance by ordering medications and helping make decisions. Both brothers call their parents regularly, yet she does “all the scrambling locally.” One brother comes to town “to give her a break” when she needs it. As this scenario implies, informal caregivers negotiate among themselves, with care unfolding over time in response to the combined influences of their lives, relational dynamics and history (see Connidis & Kemp, 2008), the presence or absence of legitimate excuses (Finch, 1989), a given AL's care resources, and residents’ needs and preferences (Kemp, 2008).

Not all convoy members have equal power or control in negotiation processes, however. Power is fluid and can be contextual, often based on an individual's position in the social structure and in a given setting. In formal–informal care negotiations, as consumers, families and residents typically have the most power. Yet, because both are dependent on others for care they also are vulnerable. Mostly because of their physical and cognitive impairments, residents are particularly vulnerable, vis à vis both family members and paid caregivers. DCWs’ vulnerability relates to their low social status and accompanying positions in the social structure, but these workers also derive a certain amount of power from being entrusted to provide hands-on care.

Care convoy outcomes

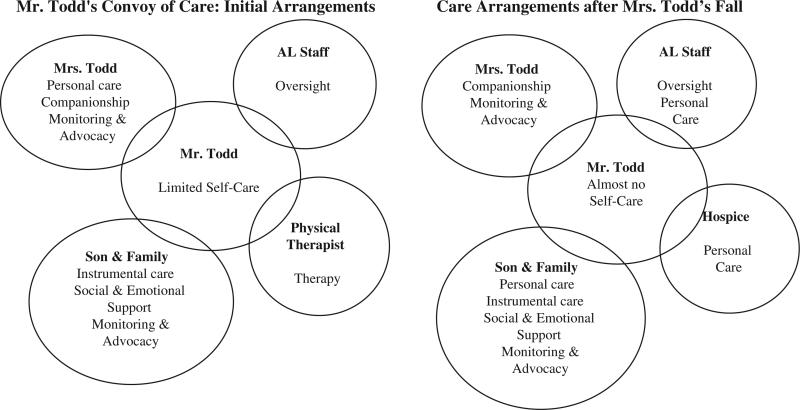

The multi-level factors identified above join to influence care convoy structures, functions, and adequacy and are implicated in residents’ and caregivers’ sense of self and identity. All of these factors can influence residents’ well-being (Perkins, Ball, Kemp, et al., 2012) and ability to age in place. These factors also have implications for formal caregivers’ sense of personal, professional, and moral affirmation, job satisfaction and retention, and perceptions of care (Ball et al., 2009; Kemp et al., 2009, 2010). Little research has examined outcomes for informal caregivers in AL (Gaugler & Kane, 2007), but potential implications for informal caregivers include satisfaction with care, levels of burden, and sense of fulfilling responsibility (see Pinquart & Sorensen, 2005). In order to more fully demonstrate the evolutionary nature of care, the potential complexity of residents’ care convoys, as well as the factors influencing convoy properties and outcomes, we offer four illustrative cases, one from S2 and three from S3, respectively represented in Figs. 2–5.

Fig. 2.

Mr. Todd's care convoy.

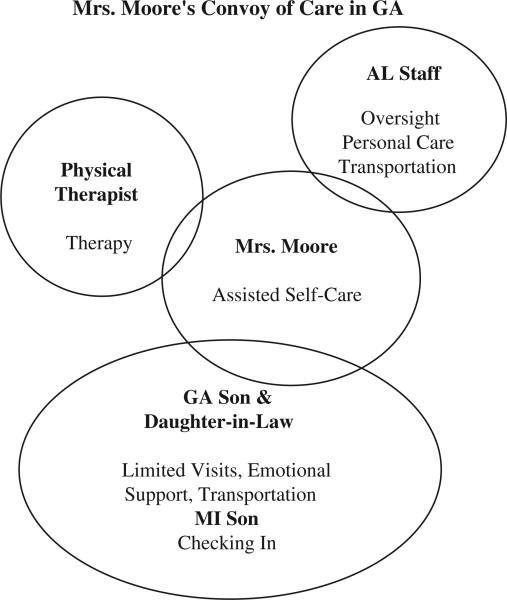

Fig. 5.

Mrs. Moore's convoy of care.

Mr. and Mrs. Todd

The Todd's, both in their 90s and married for nearly 70 years, relocated from out of state to an AL residence near their son and his family in a suburban locale after a stroke left Mr. Todd disabled. The couple shared a unit in a for-profit, corporately-owned 70-bed home, paying approximately $4250 monthly. Against the urging of her children and care staff, Mrs. Todd initially assumed all responsibility for her husband's personal care. She explained, “I took care of him. I took full charge.” The couple's informal network was highly involved in advocacy, monitoring, emotional support, and instrumental assistance. Their out-of-state daughter called daily and helped her brother with care decisions. In addition, Mr. Todd had a physical therapist coming to the home, but, as their son explained, “he wouldn't do the work” and therapy was terminated. When Mrs. Todd fell while bathing her husband, she explained how staff told her to restrict her care role: “You can't take care of him anymore. We have to give him his showers.” She relinquished his personal care. Over time, Mr. Todd declined to where, in his daughter-in-law's words, he was “beyond assisted living.” Already highly involved, his children expanded their roles and enlisted the help of Medicare-funded hospice services when Mr. Todd was giving a failure to thrive diagnosis. Their daughter-in-law commented, “We thought we were going to have to move them. Then hospice got involved and they made it a whole lot easier.” Their son explained his daily routine, “I get him up in the morning. He'd prefer not to. But, I make sure he's clean and washed and lotioned. Hospice comes in at 7:00 or 7:30 in the morning and takes care of my Dad, Monday through Friday.” Their son visits daily because in his words, “it keeps hospice and the caregivers on their toes” and “it is my responsibility.” His wife hypothesized, “I think they've not been asked to leave because my husband is there every day,” to which, he added, “Well, between my wife, myself, and the hospice... and the money we pay monthly, it's worked.” With money beginning to run out, the future was uncertain.

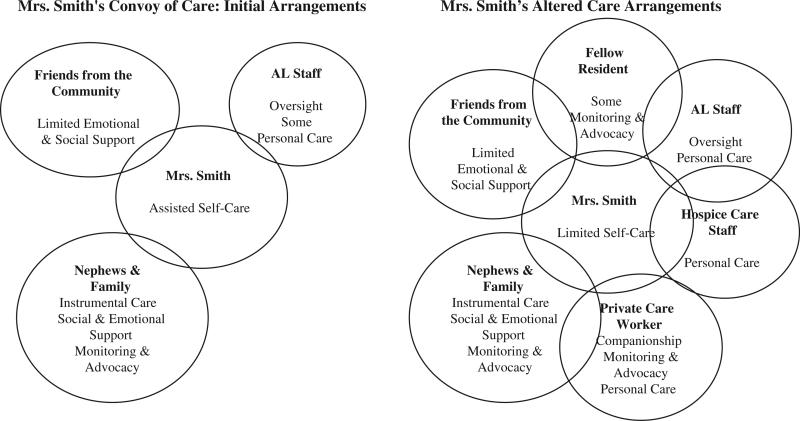

Mrs. Smith

Afflicted with Parkinson's and lung disease, Mrs. Smith relocated to the 68-bed AL building, Pineview, from her independent apartment on the shared campus of a corporately-owned for-profit senior residence. Monthly AL fees ranged from $2985–$4195 based on care needs. At the time of the move, Mrs. Smith, a long-time member of the surrounding community, was 84 and widowed; she had no children. Initially she needed AL staff assistance with select care tasks. Her informal care network consisted of two nephews, a great nephew, a niece-in-law, and, being local, a few friends from the community, and independent and AL residents. Mrs. Smith described her initial family support as “very good”, but noted it had dwindled over time. The death of her nephew who made her “feel special” was one reason for her perception of decline. Her remaining informal supporters provided her with some instrumental assistance but little socio-emotional support. Sometimes a co-resident acted as an advocate and explained, “I worry about her and I'll mention something to the care staff if I think it needs their attention.” Over time, Mrs. Smith's health worsened. After one health crisis that required hospitalization, AL staff increased Mrs. Smith's care level but eventually they became unable to manage her needs. Her family arranged for a private sitter, and Mrs. Smith began eating all meals in her room. After a second hospitalization, hospice workers joined her care convoy, enabling her to receive appropriate care and remain in AL.

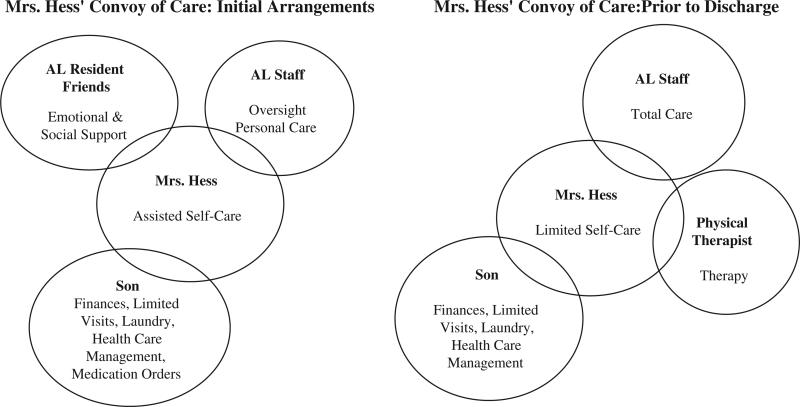

Mrs. Lottie Hess

At the age of 89, Mrs. Lottie Hess moved to Georgia to live in an apartment near her only son. Within a year of her relocation, she broke both wrists, compromising her ability to live independently. Mrs. Hess, a widow, temporarily moved in with her son and daughter-in-law while awaiting the opening of Pineview, her new residence. Upon relocating to Pineview, Mrs. Hess received some assistance from care staff with select ADLs. Her son oversaw her financial affairs, managed her health care, ordered her medications, did her laundry, and, along with his wife, visited Mrs. Hess, though “rarely.” Mrs. Hess developed an especially close relationship with Mrs. Leonard, a coresident. The two women visited and prayed together nightly until Mrs. Leonard was transferred to a nursing home. Mrs. Hess also developed a supportive relationship with Mrs. Dear, another resident who subsequently moved.

Over time, Mrs. Hess’ health declined to the point where she required a wheelchair and developed significant vision and hearing impairment, which made communication very difficult. Physical therapy was introduced as part of her regular care routine. DCWs at Pineview helped her with transfers, toileting, bathing, dressing, and getting around the facility. Staff also assisted her with medication, which Mrs. Hess’ son no longer ordered because it was “taking too much of his time.” Care staff described Mrs. Hess as “stubborn” and indicated that she “did not try to walk or do her therapy.” Without such self-care and with limited informal support from her small network, AL staff had difficulty supporting her care needs. According to one staff person, Mrs. Hess wasn't able to “stand up or anything” and required “total care”, which was “really hard” for them. Consequently, at age 96, after more than four years at Pineview, and among the longest-tenured resident, Mrs. Hess was discharged. Pineview's director cited state regulations pertaining to Mrs. Hess's inability to evacuate the building on her own. An important side note is that another resident, Mrs. Wendt, who required similarly high levels of care, was not asked to leave. Unlike Mrs. Hess, Mrs. Wendt was cooperative and had a daughter who visited her daily and was a highly active member of her care convoy. Mrs. Hess reluctantly relocated to a nearby nursing home. Fieldnote data indicate that she “cried when she had to leave to go to the nursing home” and “did not want to be over there.”

Mrs. Jenny Moore

Seventy-six year old Jenny Moore, who was divorced, relocated to Pineview from an AL residence in Texas at the insistence of her sons, Darren and Dennis. Mrs. Moore had Lupus and Parkinson's disease and alternated between using a wheelchair and a walker. Pineview's care staff managed her medications and assisted her with some ADLs, but she was able to get around and do many things on her own. She received physical therapy from an outside agency three days a week. Her out-of-state son, Darren participated at a distance through phone calls and her local daughter-in-law visited most weeks. Dennis, the in-town son, helped Mrs. Moore handle her money and get to appointments, but she often was upset with him. According to Mrs. Moore, she only saw Dennis when she had a doctor's appointment. He often grew impatient waiting for her during her appointments and, owing to his work schedule, occasionally arranged for Pineview staff to transport her. Mrs. Moore wished Dennis would take her shopping and explained that sometimes when she called to ask him to pick up supplies for her, he would tell her that she calls too much. Pineview staff felt that “children should never treat their mothers like Mrs. Moore's sons”, especially Dennis. Mrs. Moore routinely lamented having sons because she perceived that residents with daughters have more support.

Although she did not want to move, after living at Pineview for over a year, Mrs. Moore relocated to Michigan to a new AL facility near Darren. A number of factors influenced the move. First, Dennis was temporarily relocating overseas for work. Second, the new AL residence cost significantly less than Pineview. Additionally, Darren, whom she described as being more “easy going” than his brother, encouraged Mrs. Moore to come live near him. She expected that he would be more supportive than Dennis, and she perceived Dennis as growing “tired of taking care of her.” Following her move Mrs. Moore reported in telephone conversations with a researcher and a Pineview resident that she liked her new place “ok” but wanted to return to Pineview. With a hospitalized wife, Darren was not as supportive as Mrs. Moore had anticipated or hoped.

These few examples illustrate how particular care convoy properties enable certain residents to age in place in AL while other properties do not. They also show how convoy configurations vary across time in terms of who participates, how, and when. Although these cases do not show the full-range of potential care situations, it is clear that changing care needs, as well as the loss of convoy members and introduction of new ones, can redistribute care roles and responsibilities and have implications for formal and informal caregivers and care recipients alike. Indeed, informal support is “a key component of the management of resident decline” that can tip “the balance between retention and discharge” (Ball, Perkins, Whittington, Connell, et al., 2004, p. S208). Scenarios in which convoys fail to support residents sufficiently in AL can lead to residents receiving inadequate or poor quality care, feeling unsupported, as was the case for Mrs. Jenny Moore, or being transferred to a dementia care unit or a nursing home, the outcome for Mrs. Lottie Hess. Formal and informal caregivers also can experience negative outcomes, including increased care burden and potentially feelings of inadequacy and guilt.

Concluding remarks

In this article, we critique existing conceptualizations of formal–informal care relationships and, through a synthesis of theoretical and empirical knowledge, introduce a new way of studying this intersection and theorizing the connections between care convoys and caregiver and care recipient outcomes. This work contributes to and advances existing understandings of the interface between formal and informal caregivers. It uses both quantitative and qualitative findings and multi-level analysis to demonstrate that relationships between formal and informal care cannot be singularly or universally accounted for with traditional models based on hierarchy, substitution, supplementation, or even a combination of substitution and supplementation (i.e., complementary). Rather, care relationships and arrangements are much more complex.

Kahn and Antonucci's (1980) convoy metaphor is central to understanding care collaborations and relations as processes that unfold over time within the context of and in response to multi-level factors. Adding key elements of life course, social-ecological, socialist-feminist, and symbolic interactionist perspectives further highlights key features of this approach and resonates with the convoy model of social support. These features include: taking an evolutionary or longitudinal approach; understanding the role of wider social, political, and economic forces together with industry, community, facility, and individual factors and their intersections, as well as the role of negotiation, power, control, and interpretation of responsibility among and between caregivers and recipients. Importantly, care recipients are considered participants in the care process.

We illustrate the convoy of care approach in the AL context, but its basic elements apply across care settings. Applied to home settings and home care, for instance, it is necessary to account for the macro-level influences affecting the LTC work force, funding and delivery as well as industry-, community-, agency-, and individual-level forces (Dyck & England, 2012; Parks, 2003; Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003). Similarly, the model can be applied to nursing home, hospital, and hospice care settings. LTC research indicates relationships are at the core of care, and improving outcomes for care recipients and formal and informal caregivers often is about building relationships and improving social relations (Holstein et al., 2011). Home care (Bourgeault, Atanackovic, Rashid, & Parpia, 2010; Dyck & England, 2012; Parks, 2003) and nursing home (e.g., Abrahamson, Suitor, & Pillemer, 2009; Bern-Klug & Forbes-Thompson, 2008; Gladstone & Wexler, 2002a, 2002b; Shield, 2003; Utley-Smith et al., 2009; Wilson, Davies, & Nolan, 2009) research bears this out. Across settings, it is essential to take a longer, evolutionary view of care and care arrangements.

Although we have attempted to be exhaustive, additional work—both qualitative and quantitative—is needed to fully explore our proposed model. For example in AL, facility-level characteristics are important in shaping care convoy properties and outcomes. In situations where external formal caregivers such as hospice or homecare workers are involved in residents’ care convoys, agency-level influences are likely important (see Ward-Griffin & Marshall, 2003) but are not explored here. The introduction of formal caregivers external to the AL setting is relatively new. Consequently, little data exist on how these formal care workers collaborate with AL DCWs, informal caregivers, or residents. Future research would do well to investigate these relationships and to understand how agency-level factors might affect care delivery and coordination. Also needed is further research on care negotiations among informal caregivers and with residents. In addition, we did not present the full range of individual characteristics and their influence on care convoys. These are matters for future exploration.

The rapid aging of the population in the United States and elsewhere makes endeavoring to understand the complexity of formal–informal care relationships essential. The convoy of care model attempts to move beyond “simplistic causal models” and cross-sectional methods (Gaugler & Kane, 2007, pp. 95–96). We encourage others to consider drawing on this approach, including its key dimensions and variables, in order to inform empirical research, test relationships, and to spark further theoretical dialogue and refinement in studying intersections of formal and informal care in a variety of care settings.

Fig. 3.

Mrs. Smith's care convoy.

Fig. 4.

Mrs. Hess’ care convoy.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute for Aging at the National Institutes for Health (R01 AG030486-01A1 to M.M.B.), (1R01 AG021183 to M.M.B.), and the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC 756-2005-042 to C.L.K.). A version of this paper was presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Southern Gerontological Society in Raleigh, NC, USA. We wish to thank Victor W. Marshall, Malcolm P. Cutchin, Frank J. Whittington, Elisabeth O. Burgess, and Jennifer Craft Morgan for their valuable insights, feedback, and support throughout the writing process. Thank you also to Mark Sweatman, Michael Lepore, Davette Taylor Harris, Neela Lakatoo, Huali Qin, Zhinqui Li, Ramani Sambhara, April Ross, Staci Bolton, Karen Armstrong, Emmie Cochrane Jackson, Shanzhen Luo, Ailie Glover, Yarkasah Paye, Vicki Stanley, Amanda White, Terri Wylder, Navtej Sandhu, Karuna Sharma, and Sophie Carssow for their assistance in the research process. We also are very grateful to all those who participated in our AL research and generously gave their time and shared their experiences.

References

- Abrahamson K, Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Conflict between nursing home staff and residents’ families. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21(6):895–912. doi: 10.1177/0898264309340695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Personal characteristics, social support and social behavior. In: Binstock RH, Shanas E, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 2nd ed. Van Nostrand; New York: 1985. pp. 94–128. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Measuring social support networks: A hierarchical mapping technique. Generations. 1986;10(4):10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Birditt KS, Akiyama H. Convoys of social relations: An interdisciplinary approach. In: Bengston VL, Gans D, Putney NM, Silverstein M, editors. Handbook of theories and aging. 2nd ed. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Birditt KS, Sherman CW, Trinh S. Stability and change in the intergenerational family: A convoy approach. Ageing and Society. 2011;31:1084–1106. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1000098X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J. Women's sense of responsibility for the care of old people: “But who else is going to do it?”. Gender and Society. 1990;6(1):8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Neysmith S. The retreat of the state and long-term care provisions: Implications for frail elderly people, unpaid family carers and paid home care workers. Studies in Political Economy. 1997;53:37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L. Family and family-like interactions in households with round-the-clock paid foreign carers in Israel. Ageing and Society. 2009;29(5):671–686. [Google Scholar]

- Baird J, Adelman RM, Sweatman WM, Perkins MM, Ball MM. Job satisfaction and racism in the service sector: A study of work in assisted living. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Lepore MJ. “We do it all”: Universal workers in assisted living. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010a. pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Lepore MJ, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Sweatman WM. “They are the reasons I come to work”: Staff–resident relationships in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2009;23(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM. Research overview. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Connell BR, Hollingsworth C, King SV, et al. Managing decline in assisted living: The key to aging in place. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004a;59B:S202–S212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.s202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Independence in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies. 2004b;18(4):467. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Combs BL. Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ. Surviving dependence: Voices of African American elders. Baywood Publishing Company, Inc.; Amityville, New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Perkins MM, Patterson VL, Hollingsworth C, King SV, et al. Quality of life in assisted living facilities: Viewpoints of residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2000;19:304–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bern-Klug M, Forbes-Thompson S. Family members’ responsibilities to nursing home residents: “She is the only mother I got”. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2008;34(2):43–52. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20080201-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic interaction: Perspective and method. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeault IL, Atanackovic J, Rashid A, Parpia R. Relations between immigrant care workers and older persons in home and long-term care. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2010;29(1):109–118. doi: 10.1017/S0714980809990407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti T. Theorizing feminist gerontology, sexuality, and beyond: An intersectional approach. In: Bengtson VL, Silverstein M, Putney MM, Gans M, editors. Handbook of theories of aging. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 471–485. [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti T, Slevin KF. Gender, social inequalities, and aging. Altamira; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti T, Zajicek A. A socialist-feminist approach to aging: Embracing diversity. Journal of Aging Studies. 1993;7:117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. Neighbors and friends: An overlooked resources in the informal support system. Research on Aging. 1979;1:434–463. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. Family and community: Changing roles in an aging society. The Gerontologist. 1991;31(3):337–346. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder PC, Morgan LA, Eckert JK. Small board-and-care homes: A fragile future. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. The Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2008. pp. 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright JC, Miller L, Volpin M. Hospice in assisted living: Promoting good quality care at end of life. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):508–516. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control National survey of residential care facilities. 2010 (Retrieved from: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Datasets/NSRCF/2010/)

- Chappell N, Blandford A. Informal and formal care: Exploring the complementarity. Ageing and Society. 1991;11:299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA. Family ties and aging. 2nd ed. Pine Forge; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA, Kemp CL. Negotiating actual and anticipated parental support: Multiple sibling voices in three-generation families. Journal of Aging Studies. 2008;22:229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Dyck I, England K. Homes for care: Reconfiguring care relations and practices. In: Ceci C, Bjornsdottir K, Purkis ME, editors. Perspectives on care at home for older people. Routledge; New York: 2012. pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JK, Carder PC, Morgan LA, Frankowski AC, Roth EG. Inside assisted living: The search for home. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr. The life course and human development. In: Lerner RM, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. 5th ed. Vol. 1. Wiley and Sons; New York: 1998. pp. 939–991. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Jr., Clipp EC. Wartime loss and social bonding. Psychiatry. 1988;51:177–198. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1988.11024391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch J. Family obligations and social change. Basil Blackwell; Cambridge, MA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Finch J, Mason J. Negotiating family responsibilities. Routledge; London: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE. Family involvement in residential long-term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:105–118. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331310245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Kane RL. Families and assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:82–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J, Wexler E. The development of relationships between families and staff in long-term care facilities: Nurses’ perspectives. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2002a;21:217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone J, Wexler E. Exploring the relationships between families and staff caring for residents in long-term care facilities: Family members’ perspectives. Canadian Journal on Aging. 2002b;21:39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. Do impaired older persons with health care needs occupy U.S. assisted living facilities? An analysis of six national studies. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S68–S79. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golant SM. The future uncertainty of assisted living residences: A response to uncertainty. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2008. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Greene V. Substitution between formally and informally provided care for the impaired elderly in the community. Medical Care. 1983;21(6):609–619. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium JF. Family responsibility and caregiving in the qualitative analysis of the Alzheimer's disease experience. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1988;50:197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein MB. Home care, women, and aging: A case study of injustice. In: Walker MU, editor. Mother time: Women, aging, and ethics. Rowman & Littlefield; New York, NY: 1999. pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein MB, Parks JA, Waymack MH. Ethics, aging, and society. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J, Perez R, Reed PS. The old road is rapidly aging: A social model for cognitively and physically impaired elders in assisted living's future. In: Golant SM, Hyde J, editors. The assisted living residence: A vision for the future. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2008. pp. 46–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL. Aging and social support. In: Riley WM, editor. Aging from birth to death. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1979. pp. 72–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RL, Antonucci TC. Convoys over the life course: A life course approach. In: Baltes PB, Brim O, editors. Life span development and behavior. Academic Press; New York: 1980. pp. 253–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Negotiating transitions in later life: Married couples in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2008;27(3):231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL. Married couples in assisted living: Adult children's experiences providing support. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:639–661. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Lepore MJ. Connections with residents: “It's all about the residents for me”. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. pp. 145–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, Perkins MM. Strangers and friends: Residents’ social careers in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2012;67:491–502. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Lepore MJ. “I get along with most of them”: Direct care workers’ relationships with residents’ families in assisted living. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(2):224–235. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last Acts . Means to a better end: A report on dying in America. Last Acts National Program Office; Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore MJ, Ball MM, Perkins MM, Kemp CL. Pathways to caregiving. In: Ball MM, Perkins MM, Hollingsworth C, Kemp CL, editors. Frontline workers in assisted living. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2010. pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Litwak E. Helping the elderly: The complementary roles of informal networks and formal systems. Guildford Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H, Attias-Donfut C. Inter-relationship between formal and informal care: A study in France and Israel. Ageing and Society. 2009;29(1):71–91. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X08007666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH. Formal and informal support: The great divide. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999;14:183–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Matthews A. Situating ‘home’ at the nexus of the public and private spheres: Ageing, gender and home support work in Canada. Current Sociology. 2007;55:229–249. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley WJ, Travis SS, Safewright M. The relationship between formal and informal health care services for the elderly. In: Stahl SM, editor. The legacy of longevity: Health and health care in later life. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RL. Aging in place in assisted living: State regulations and practice. American Seniors Housing Association; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Social ecological perspectives on health. In: Stone GC, Coeh F, Adler NE, editors. Health psychology: A handbook. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1979. pp. 523–547. [Google Scholar]

- Munn JC, Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Mitchell CM. Is hospice associated with improved end-of-life care in nursing home and assisted living facilities? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:490–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving. AARP A focused look at those caring for someone 50 years or older: Caregiving in the U.S. 2009.