Abstract

The involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) has known to be limited to the brain, brain stem, and cerebellum. Herein, we report an 11-year-old boy who presented with neurological symptoms and was diagnosed as FHL by molecular diagnosis. The hemophagocytic lesions in the CNS were shown to extend to the thoracal level of spinal cord which completely disappeared after the completion of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-2004 protocol.

Keywords: Central nervous system, familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, spinal cord involvement, UNC13D gene mutation

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of activated lymphocytes and histiocytes leading to organ infiltration such as liver, spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, skin, and central nervous system (CNS).[1] Reports on the frequency of CNS involvement of HLH are still limited. Janka reported cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities in 17 of a series of 33 patients, but neurological symptoms in less than 10% of these patients with HLH.[2]

Three different neuropathological stagings of HLH have been established: Stage 1 - leptomeningeal infiltrates of lymphocytes and histiocytes only; stage 2 - additional adjacent parenchymal involvement with perivascular infiltration; stage 3 - massive tissue infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes and the presence of tissue necrosis.[3] Although cerebral involvement of HLH is well-defined; up to our knowledge, spinal cord involvement of CNS hemophagocytosis has not been described in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) yet. Herein, we report an 11-year-old boy diagnosed with FHL confirmed by UNCD13 gene mutation showing extensive cerebral, cerebellar, and spinal cord involvement.

Case Report

An 11-year-old boy was referred for on-going splenomegaly subsequent to tonsillopharyngitis 5 months ago. He was the second child born to consanguineous parents and his brother died of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated HLH 2 years ago. Unfortunately, molecular analysis for HLH was unavailable for his brother.

At the first presentation, he was conscious, alert, and afebrile. Only the spleen was palpable 4 cm below the left costal margin. Neurological examination was completely normal. Complete blood count revealed hemoglobin: 10.6 g/dL, platelet: 105 × 109/L, and leukocyte count: 2.6 × 109/L with an absolute neutrophil count of 1.1 × 109/L. Serum liver adrenal function tests and electrolytes were normal. Serum ferritin level was 24.4 ng/mL. Serum fasting triglyceride and plasma fibrinogen levels were 113 mg/dL and 250 mg/dL respectively. Bone-marrow aspiration demonstrated increased histiocytes and hemophagocytosis. Polymerase chain reaction for EBV DNA revealed 12.909 copies/mL and parenteral acyclovir therapy was commenced immediately.

A week later, he began to suffer from persistent headache unresponsive to analgesics and vomiting. Fundoscopic examination showed bilateral papilledema. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed bilateral symmetric signal changes on the periventricular deep white matter and increased micronodular contrast uptake on the right cerebellar hemisphere on T2w images which were suggestive for HLH involvement of CNS. Cervical spinal cord was normal. CSF examination yielded increased pressure (140 cm H2O) with normal protein and glucose levels. Cytological evaluation showed prominent lymphomononuclear cells, pointing to pleocytosis. Preliminary diagnosis was thought as EBV-associated HLH and intravenous gamma globulin – together with dexamethasone and cyclosporine – was given. Intrathecal chemotherapy with methotrexate and prednisolone was performed once a week, for 4 weeks. At the end of the 3rd week, splenomegaly disappeared and EBV copies decreased to 212 copies/mL. He was discharged from the hospital, with normal CSF values.

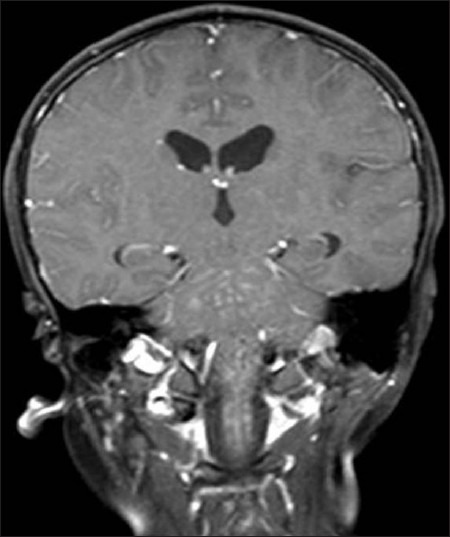

On the 7th week of follow-up as an outpatient – while receiving cyclosporine A and dexamethasone – he presented with headache, vomiting, and somnolence again. He was confused but responded to verbal stimuli. Bilateral papilledema was noticed on fundoscopic evaluation. Mild quadriparesia was also noted and deep tendon reflexes were hypoactive. Cranial MRI demonstrated apparent progression of the previous cerebral and cerebellar lesions and involvement of brain stem and cervical spinal cord. The lesions were extended to the level of 6th thoracal segment [Figure 1a–c]. CSF and serum EBV copies were negative. Cytological evaluation of CSF revealed reappearance of lymphomononuclear cells with prominent hemophagocytosis. HLH criteria including ferritin, fibrinogen, and triglyceride were unremarkable.

Figure 1a.

On coronal T1W image, widespread hyperintense punctate lesions in the brainstem and observable upper spinal cord in addition to the brain parenchyma

Figure 1c.

Following intravenous gadolinium-based contrast agent, the punctate lesions enhance in a perivascular fashion on sagittal post-contrast T1W image (TR/TE; 580/15 ms)

Figure 1b.

The spinal cord is diffusely swollen and T2 hyperintense with punctate hypointense foci on the sagittal T2W image

Molecular analysis for FHL yielded a mutation in UNC13D gene which is c.1240C > T leading to p.Arg414Cys substitution. Due to recurrent CNS HLH and UNC13D mutation, he was diagnosed as FHL. HLH-2004 protocol including etoposide was initiated with the consent of his family.[4] The clinical and biochemical findings remitted at the 4th week of the protocol. The radiological findings completely disappeared after the end of HLH 2004 protocol. He underwent a successful bone-marrow transplantation from a HLA-mismatched donor (9/10). He is alive and healthy now.

Discussion

FHL is a rare disorder with very high mortality rates, mainly affecting infants and young children. Neurological involvement is of great importance which may even dominate and or precede the systemic presentation. CNS involvement is present at the onset of the disease with a rate ranging from 20% to 70%. The symptoms may change in a wide spectrum, ranging from irritability, bulging fontanelle, neck stiffness, headache, convulsions, cranial nerve palsies, ataxia, hemiplegia/tetraplegia, and stupor to coma. In addition, some patients have been reported to be free of signs and symptoms, despite the CNS involvement.[5]

Mutations of PRF1, UNC13D, and Syntaxin11 genes that cause FHL have been described. PRF1 mutations were detected in 20-40% of the patients. UNC13D and STX11 gene mutations were found to affect 20% and 10% of patients respectively.[6,7] In a study which compares genotype-phenotype correlation in FHL, patients carrying PRF1 mutations had a higher risk of early onset, but without identified mutations, had an increased risk of CNS involvement compared to patients with STX11.[8] In our previous study, we reported CNS involvement in six of nine patients with PRF1 mutations but only two presented with isolated CNS symptoms at the diagnosis.[9] In the present case, we describe a missense mutation in UNC13D gene which is c.1240C > T leading to p.Arg414Cys substitution.

In neuropathological evaluations of CNS HLH, it has been shown that infiltration of the leptomeninges by lymphocytes and histiocytes (stage 1) is the most common and mildest presentation in HLH patients with CNS involvement. Whereas in more advanced cases, adjacent parenchymal involvement with perivascular infiltration can be seen (stage 2). In stage 3, diffuse parenchymal infiltration with multifocal necrosis and prominent astrogliosis are present.[3] CSF analysis in HLH often shows pleocytosis with elevated protein levels as in our patient.

The lymphohistiocytic infiltration of cerebral parenchyma can be detected by computed tomography (CT) and MRI techniques. Reported CT findings include atrophy, focal hypodensities, calcification, parenchymal hemorrhages mimicking child abuse, and enhancing leptomeningeal lesions.[10,11] The most frequently reported MRI findings are periventricular white matter signal abnormalities and cerebral volume loss with enlargement of ventricles.[12] Multiple focal-enhancing T2-weighted bright lesions scattered throughout the brain mimicking septic emboli have also been described. Similar white matter changes can be detected as elevated lactate and choline peaks by MR spectroscopy correlated with perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. These lesions may be misinterpreted as infections or demyelination disorders.[11]

The second cranial MRI of our patient demonstrated that the lesions suggesting the HLH extended to the level of sixth thoracal vertebra. Spinal cord involvement has not been reported in FHL yet. Yagi et al. reported a case who developed secondary HLH and poliomyelitis-like flaccid paralysis due to Chlamydia pneumonia.[12] But spinal MRI findings suggested inflammatory changes rather than HLH in that case. Parental consanguinity and sibling history suggested but molecular analysis confirmed FHL in our patient.

Herein, we reported spinal cord involvement in FHL for the first time. It is probably related to ordering cranial, but not spinal imaging. We, therefore, recommend spinal imaging for all patients with the diagnosis of FHL to see if spinal cord is involved.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:95–109. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janka GE. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140:221–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00443367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henter JI, Nennesmo I. Neuropathologic findings and neurologic symptoms in twenty-three children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Pediatr. 1997;130:358–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurgey A, Aytac S, Balta G, Oguz KK, Gumruk F. Central nervous system involvement in Turkish children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1293–9. doi: 10.1177/0883073808319073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldmann J, Callebaut I, Raposo G, Certain S, Bacq D, Dumont C, et al. Munc13-4 is essential for cytolytic granules fusion and is mutated in a form of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL3) Cell. 2003;115:461–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.zur Stadt U, Schmidt S, Kasper B, Beutel K, Diler AS, Henter JI, et al. Linkage of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL) type-4 to chromosome 6q24 and identification of mutations in syntaxin 11. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:827–34. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horne A, Ramme KG, Rudd E, Zheng C, Wali Y, al-Lamki Z, et al. Characterization of PRF1, STX11 and UNC13D genotype-phenotype correlations in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okur H, Balta G, Akarsu N, Oner A, Patiroglu T, Bay A, et al. Clinical and molecular aspects of Turkish familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis patients with perforin mutations. Leuk Res. 2008;32:972–5. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozgen B, Karli-Oguz K, Sarikaya B, Tavil B, Gurgey A. Diffusion-weighted cranial MR imaging findings in a patient with hemophagocytic syndrome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1312–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turtzo LC, Lin DD, Hartung H, Barker PB, Arceci R, Yohay K. A neurologic presentation of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis which mimicked septic emboli to the brain. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:863–8. doi: 10.1177/0883073807304203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decaminada N, Cappellini M, Mortilla M, Del Giudice E, Sieni E, Caselli D, et al. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Clinical and neuroradiological findings and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:121–7. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-0957-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]