Federal inmates in the Canadian correctional system receive substantially varied health care that does not measure up to that of other Canadians, according to experts in the prison health care system.

Correctional Service Canada (CSC) is responsible for providing an estimated 15 055 federal prisoners with “essential health care” that “conform[s] to professionally accepted standards,” according to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-44.6/).

But experts say the level of care is more often than not substandard and varies widely across the correctional system, which would mean that CSC is breaking its own rules.

“The quality of care is not the same across the board,” says Howard Sapers, the correctional investigator for Canada, whose office of 32 independent federal employees conducts yearly investigations inside institutions and makes recommendations to CSC in an annual report.

“In fact the biggest single complaint that my office has received for the last decade has been access to equality of health care, and that’s everything from acute mental health services to dentistry.”

The lack of attention and desire to seek reform on inequality of care within the federal correctional system falls on the CSC and Public Safety Canada, says Libby Davies, NDP health critic and Member of Parliament for Vancouver East. Davies adds that despite comprehensive, eye-opening annual reports from the office of the Correctional Investigator for Canada on the challenges facing the Canadian prison health care system, recommendations and inadequacies are largely ignored.

“It’s a matter of statutory requirements, of fair standards,” she says. “It’s a question of the law, it’s a question of paying attention to the correctional investigator’s reports; that’s what he is there for is to actually monitor the system, and when an independent issues reports than you’ve got to pay attention to them.”

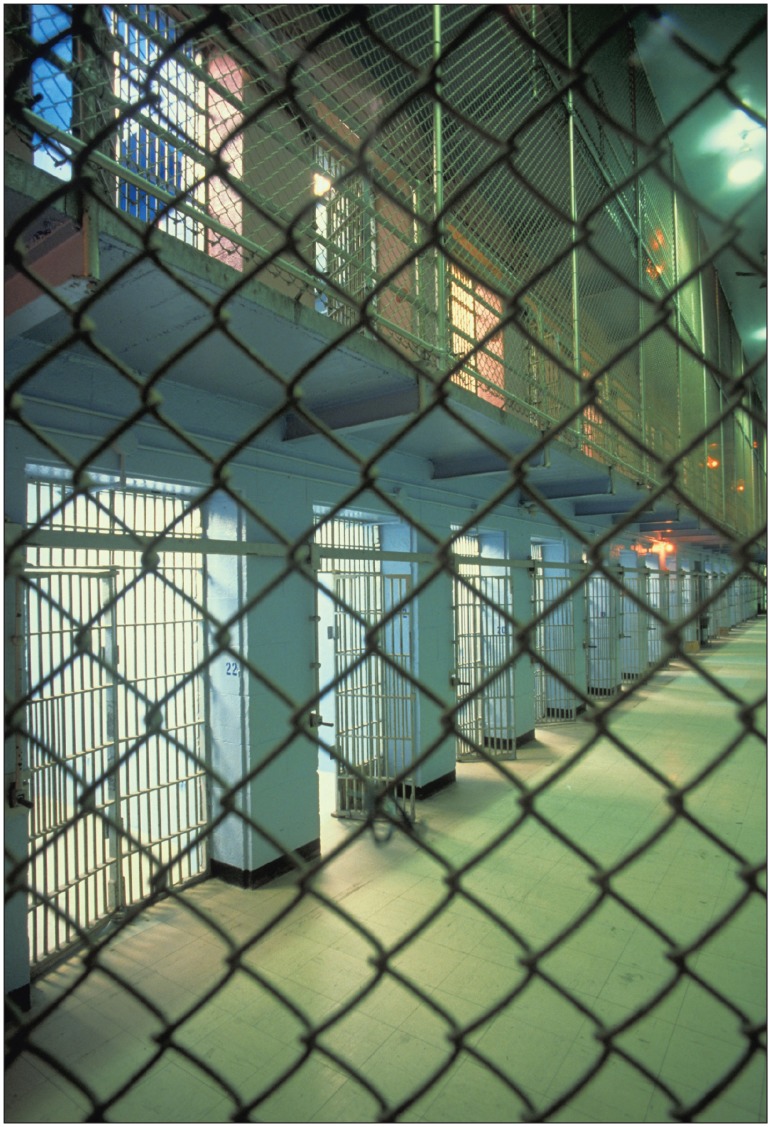

The level of health care within the walls of prisons is often substandard and varies widely across the correctional system.

Image courtesy of © 2013 Thinkstock

“I think it’s a deeply systemic issue, but if you don’t have the leadership that’s actually paying attention to … what’s been going on for years, how will change be brought about?”

Public Safety Minister Vic Toews declined to comment.

CSC does provide a response to the recommendations in the annual reports of the Correctional Investigator, which more often than not support the principles but not any concrete changes (www.csc-scc.gc.ca/text/pblct/ci11-12/ci11-12-eng.shtml).

There have been countless examples of treatments taking significantly longer for the inmate population than for other Canadians, says Cat Baron, president of the Elizabeth Fry Society of Ontario, an organization that provides assistance to men involved in the criminal justice system.

“We absolutely know there is a substandard and a different level of health care within the prison system,” she says. “Unquestionably, we have loads of documented examples that there is a difference. By law there should not be; by law they are to be provided with the same level of health care that they would be provided in the communities.”

Baron adds that prisoner complaints and reports of medical complications demonstrate that health care is fundamentally different within prison walls.

“We have a case ongoing now in which a doctor had said that a woman’s hepatitis C levels were too high and that she needed an outside specialist appointment,” she says. “It’s been basically a year and a half that it was going on, and it hasn’t even been remedied.”

Another case Baron encountered first hand was a woman with a severe dental infection who was only being treated in the prison with antibacterial mouth wash.

“Six months later she finally gets out to see a dentist, and he says ‘the infection is so severe I can’t even do the root canal until it’s been cleared up.’”

“Sometimes it’s a significantly longer period of time … we’re talking sometimes years.”

Unexpected difficulties can arise as CSC tries to provide timely and effective health care in accordance with the Act. These difficulties include safety concerns. Security is always an issue when providing care to inmates, whether inside prisons or outside in hospitals.

Baron says her organization has encountered numerous examples of prison nurses who say they are actively dissuaded from making external health care appointments for inmates.“ It costs money to get prison guards to escort women to an outside appointment which is why they’re actively discouraged from arranging an outside appointment.”

Add to this the fact that prisoners are often seen as attention-seeking and drug-seeking, it’s no wonder their access to care is hampered, Baron says. “If they complain about health care they are routinely not believed,” she says. “There is kind of an ‘us and them’ attitude toward prisoners that is a barrier to effective medical care right away. So the largest number of complaints we get where the situation has grown to intolerable proportions are because they simply haven’t been believed.”

Access to medical doctors in prisons and their level of training can also vary among institutions, says Kim Pate, executive director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies.

“They have doctors who work in the area that they do because they’re dedicated to that area — or maybe because they have no other option,” she says. “You may not have very good doctors quite frankly in terms of their ability to interact with individuals.”

Pate adds that in addition to these difficulties, prison doctors may be in a facility only once a week or month depending on the size of the institution, and the problem can be magnified due to the relatively small physician pool available to federal inmates (www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.109-4389).

The rising level of overcrowdedness in institutions compounds the problem of inadequate and varied health care for prisoners, says Catherine Latimer, executive director of the John Howard Society of Canada.

“When you have more and more inmates being packed into a certain institution, usually what you don’t see is a commensurate increase in the available programs — whether that be in training and rehabilitation programs or just basic health care needs programs,” she says. “So you’re providing the same level of services divided over a greater number of people in need and that raises some real problems over continuing levels of adequacy.”