Abstract

Nitric oxide synthases (NOS) catalyze to produce nitric oxide (NO) from L-arginine. The isoform of NOS i.e. inducible nitric oxide synthases (iNOS) expression is observed in various human malignant tumors such as breast, lung, prostate and bladder, colorectal cancer, and malignant melanoma. Also an increased level of iNOS expression and activity has been found in the tumor cells of gynecological malignancies, stroma of breast cancer and tumor cells of head and neck cancer. Because of its importance in causing tumors and cancer, iNOS enzyme has become a new target in finding novel inhibitors as anti cancer agents. The present work focuses on the molecular docking analysis of quercetin and its analogues against iNOS enzyme. Earlier there are reports of quercetin inhibiting iNOS enzyme in certain experiments as anti cancer agent. But the clinical use of quercetin is limited by its low oral bioavailability and therefore needed its molecular modification to improve its pharmacological properties. In the present study ten analogues of quercetin were found to be docked at the active site cavity with favorable ligand-protein molecular interaction and interestingly from the ADME-Toxicity analysis these analogues have enhanced pharmacological properties than quercetin.

Keywords: Inducible iNOS, Molecular docking, Molecular modification, Cancer, Analogues

Background

Nitric oxide synthases (NOS) (EC 1.14.13.39) are a family of enzymes that catalyze producing nitric oxide (NO) from L-arginine. It is an important cellular signaling molecule, having a role in various cellular processes. The free radical (NO) is an important effector molecule in the nervous, immune and cardio vascular systems (Garthwaite and Boulton 1995; MacMicking et al. 1997; Michel and Feron, 1997). Mammals contain three isoforms of NOS that produce NO and citrulline by catalyzing NADPH and O2 dependent oxidation of L-arginine (Griffith and Stuehr 1995; Marletta et al. 1997). Two isoforms of NOS are expressed in cells such as neurons (nNOS) and endothelium (eNOS) which are activated by Ca+2 dependent calmodulin (CaM) binding and the third inducible isoform (iNOS) is induced by cytokines which binds CaM independently (Ghosh et al., 1999). The iNOS isoform is a homodimer (Michal 1999) and the iNOS gene is located on chromosome 17 (Xu et al. 1994). iNOS exerts its functions independent of Ca+2 while calmodulin remains non-covalently bound to the iNOS complex and forms an essential subunit of the isoform (Knowles and Moncada 1994, Cho et al. 1992). Regulating NO production via iNOS necessarily occurs during transcription and translation, for once active, iNOS synthesizes large amounts of NO until substrate depletion (Hickey et al. 2001). The role of NO affects the expression and activity of oncogenes, which are vital to the cell cycle and apoptosis (Forrester et al. 1996; Messmer et al. 1994; Sandau et al. 1997). Forrester et al. observed an up regulation of the tumor suppressor gene p53 after the exposure of cells to NO donors which might be a reaction due to NO mediated DNA damage (Forrester et al. 1996). Also, the p53 gene is an important inhibitor for iNOS expression as it regulates NO production by a negative feedback loop mechanism. The non-mutant p53 protein (wild-type form) binds to a site on the iNOS gene, preventing its transcription (Brennan and Moncada 2002). Thus, suggesting the wild-type p53 is vital for the control of NO mediated genotoxicity (Forrester et al., 1996). Certain experiments with mutant p53 animal tumors have found out there is an increase in NOS activity in such cancers which grew faster with greater angiogenic potential. Thus, promoting cancer progression by providing a selective growth advantage to tumor cells (Ambs et al. 1998a). NO could also be shown to activate p53 resulting in anti-carcinogenic effects, mutagenic and increase cancer risk (Goodman et al. 2004, Rao 2004). The multifactorial process involved in carcinogenesis requires mutations in somatic cells and subsequent alterations of morphology and growth pattern, eventually resulting in transformation, local invasion, and metastasis (Lirk et al. 2002). The expression of iNOS can be observed in a various human malignant tumors such as breast (Vakkala et al. 2000), lung (Marrogi et al. 2000), prostate (Aaltoma et al. 2001; Aaltomaa et al. 2000; Uotila et al., 2001) and bladder (Swana et al. 1999; Hayashi et al. 2001), colorectal cancer (Kojima et al. 1999), and malignant melanoma (Massi et al. 2001). However, there are many conflicting reports that increased levels of iNOS are not a ubiquitous finding in human cancer and its expression depends on the histological type or grade of the tumor and the tumor stage (Crowell et al. 2003; Kinaci et al. 2012). Various studies have also found out the expression and the activity of iNOS in human cancer (Weiming et al. 2002; James et al. 2003). An increased level of iNOS expression and activity has been found in the tumor cells of gynecological malignancies, (Thomsen et al., 1994) in the stroma of breast cancer, (Thomsen et al. 1995) and in the tumor cells of head and neck cancer (Gallo et al. 1998; Franchi et al. 2002). Several studies have reported an increase of iNOS expression in tumor tissue when compared with normal mucosa (Ambs et al. 1998b; Ambs et al. 1999; Ropponen et al. 2000; Yagihashi et al. 2000; Kojima et al. 1999; Hao et al. 2001).

The present work aims on molecular docking analysis of iNOS enzyme against a class of flavonoid (quercetin and its analogues) which is present in fruits, vegetables, leaves and grains and is reported to have effective anti-cancer property. Scientists have long considered quercetin and flavonoids present in fruits, vegetables, leaves and grains important in cancer prevention. There are also reports of lower risk of cancer in people who eat more fruits and vegetables. (Verschoyle et al. 2007; Rietjens et al. 2005; van der Woude et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2001). Interestingly, quercetin inhibiting against iNOS as anti cancer agents has been reported by García-Mediavilla et al. and Raso et al. (García-Mediavilla et al. 2007; Raso et al. 2001). But the clinical use of quercetin is limited by its low oral bioavailability (Peng et al. 2008) and therefore compels its molecular modification to enhance its pharmacological properties. In the present study the best docking hit analogues were undergo ADME–Toxicity prediction (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and toxicity) to evaluate its pharmacological properties to be an orally active compound. Here in the present work, we are reporting for the first time the analogues of quercetin as iNOS inhibitors with enhanced pharmacological properties.

Results and discussion

Molecular docking analysis

Quercetin (3,3’,4’,5,7-pentahydroxylflavone) is a plant derived flavonoid which is present in the plant kingdom as a secondary metabolite. It is the most well defined group of polyphenolic compounds (Murakami et al., 2008). The flavonoids contain a basic skeleton of diphenylpropane (C6–C3–C6). Quercetin is commonly found as O-glycosides with one of its hydroxyl group is substituted by sugars of various type. In this report, we have highlighted molecular docking studies on the inhibition of iNOS by quercetin and its analogues. Molecular docking was carried out using Molegro Virtual Docker, MVD 5.0 (Molegro 2011). The top poses were found to be lying deep into the binding cavity of iNOS enzyme showing all the major interaction and a favourable interaction energy than quercetin ranging from −130.62 to −150.44 compared with −97.17of quercetin. The top docking hits were bound within the active site cavity consisting of the protoporphyrin IX containing Fe (HEM) revealing molecular interaction with the active site residues and HEM. The analogues docked at the binding cavity have a rerank score ranging from −104.75 (CID5281604) to −65.79 (quercetin) as shown in Table 1. The rerank score is a linear combination of E-inter (steric, Van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic) between the ligand and the protein, and E-intra (torsion, sp2-sp2, hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals, electrostatic) of the ligand weighted by pre-defined coefficients (Thomsen and Christensen 2006). Also, the top three docking hits have a MolDock score of −129.14 for CID5281604, −122.90 for CID5315126, −133.99 for CID9818879 and −77.29 for quercetin.

Table 1.

Docking score of the top docking hits and quercetin

| SN | Ligand | MolDocka | Rerankb | Interactionc | Internald | HBonde | LE1f | LE3g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5281604 | −129.14 | −104.75 | −148.27 | 19.14 | −11.81 | −5.61 | −4.55 |

| 2 | 5315126 | −122.90 | −102.63 | −146.11 | 23.21 | −15.38 | −4.55 | −3.80 |

| 3 | 9818879 | −133.99 | −95.04 | −150.44 | 16.46 | −9.33 | −5.58 | −3.96 |

| 4 | 5481966 | −122.87 | −93.67 | −141.73 | 18.86 | −2.43 | −4.55 | −3.47 |

| 5 | 5282154 | −116.71 | −93.58 | −135.98 | 19.27 | −14.02 | −4.86 | −3.90 |

| 6 | 13964550 | −113.94 | −93.40 | −130.62 | 16.68 | −4.56 | −5.18 | −4.25 |

| 7 | 5281691 | −124.63 | −92.63 | −144.57 | 19.94 | −7.95 | −5.42 | −4.03 |

| 8 | 11834044 | −116.92 | −91.50 | −140.67 | 23.75 | −13.46 | −5.08 | −3.98 |

| 9 | 6477685 | −130.50 | −91.09 | −144.13 | 13.63 | −4.18 | −5.67 | −3.96 |

| 10 | Quercetin | −77.29 | −65.79 | −97.17 | 19.88 | −8.42 | −3.51 | −2.99 |

a - Moldock score is derived from the PLP scoring functions with a new hydrogen bonding term and new charge schemes. (Thomsen and Christensen 2006).

b - The rerank score is a linear combination of E-inter (steric, Van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic) between the ligand and the protein, and E-intra. (torsion, sp2-sp2, hydrogen bonding, Van der Waals, electrostatic) of the ligand weighted by pre-defined coefficients. (Thomsen and Christensen 2006).

c - The total interaction energy between the pose and the protein (kJ mol−1).

d - The internal energy of the pose.

e - Hydrogen bonding energy (kJ mol−1).

f - Ligand Efficiency 1: MolDock Score divided by Heavy Atoms count.

g - Ligand Efficiency 3: Rerank Score divided by Heavy Atoms count.

The MolDock scoring function (MolDock Score) is derived from the PLP scoring functions originally proposed by Gehlhaar et al. (Gehlhaar et al. 1995, Gehlhaar et al. 1998) and later extended by Yang et al. (Yang and Chen 2004). The MolDock scoring function further improves these scoring functions with a new hydrogen bonding term and new charge schemes. The docking scoring function, Escore, is defined by the following energy terms:

Where,

Einter is the ligand-protein interaction energy

Eintra is the internal energy of the ligand

Also the hydrogen bonding energy which describes the binding affinity for the docked compounds ranges from −15.38 kJ mol-1 for CID5315126 to −2.43 for CID5481966 while quercetin have a hydrogen bonding energy of −8.42 kJ mol-1.

The ligand-protein interaction analysis for the top ten docking hits was calculated using MVD ligand energy inspector. The ligand–protein interaction including the residues present, their interaction distances and interaction energy and the interacting atoms of the protein and the ligand is shown in Table 2. The molecular docking simulation revealed that the top docking poses were found to be docked into the binding cavity displaying both bonded and non bonded interaction.

Table 2.

Molecular interaction analysis of the top three docking hits and quercetin

| SN | Compound ID | Interacting Atom ID and Name (Ligand) | Interacting Atom Name (Protein/Cofactor) | Interaction Energy (kJ mol−1) | InteractionDist. (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CID5281604 | 5(O) | O(Phe369) | −2.43 | 3.04 |

|

5(O) | N(Val352) | −1.71 | 3.26 | |

| 4(O) | OD2(Asp382) | −2.5 | 2.97 | ||

| 4(O) | NE1(Trp346) | −0.18 | 3.54 | ||

| 4(O) | OH(Tyr347) | −2.5 | 3.0 | ||

| 4(O) | OH(Tyr373) | −2.5 | 2.77 | ||

| 8(O) | N(HEM) | −2.5 | 3.10 | ||

| 8(O) | N(HEM) | −2.5 | 2.87 | ||

| 2 | CID5315126 | 3(O) | NE1(Trp346) | −0.02 | 3.59 |

|

3(O) | OH(Tyr347) | −2.5 | 3.06 | |

| 3(O) | OH(Tyr373) | −2.11 | 2.55 | ||

| 3(O) | OD2(Asp282) | −2.5 | 3.07 | ||

| 1(O) | OD1(Asp382) | −2.5 | 2.65 | ||

| 1(O) | NH2(Arg388) | −1.1 | 3.26 | ||

| 1(O) | NH1(Arg388) | −1.78 | 3.10 | ||

| 6(O) | O(Pro350) | −1.98 | 2.54 | ||

| 6(O) | N(Gly371) | −0.88 | 2.77 | ||

| 2(O) | O(HEM) | −2.5 | 2.60 | ||

| 4(O) | N(HEM) | −1.03 | 3.39 | ||

| 3 | CID9818879 | 4(O) | OD1(Asp382) | −2.0 | 3.07 |

|

4(O) | OD2(Asp382) | −1.7 | 3.09 | |

| 5(O) | OD1(Asp382) | −2.5 | 3.10 | ||

| 5(O) | OH(Tyr347) | −1.8 | 3.25 | ||

| 3(O) | O(Pro350) | −1.4 | 3.31 | ||

| 6(O) | O(HEM) | −2.5 | 3.10 | ||

| 6(O) | O(HEM) | −2.5 | 2.77 | ||

| 4 | Quercetin | 6(O) | OD1(Asp382) | −2.5 | 2.60 |

|

6(O) | NH1(Arg388) | −2.26 | 3.08 | |

| 5(O) | NE2(Gln263) | −0.34 | 2.35 | ||

| 4(O) | O(Pro350) | −2.5 | 2.75 | ||

| 4(O) | N(Gly371) | −0.82 | 2.66 | ||

| 1(O) | O(HEM) | −2.5 | 3.10 | ||

| 1(O) | O(HEM) | −2.5 | 2.68 | ||

| 2(O) | N(HEM) | −0.4 | 3.52 |

HEM - Protoporphyrin IX containing Fe.

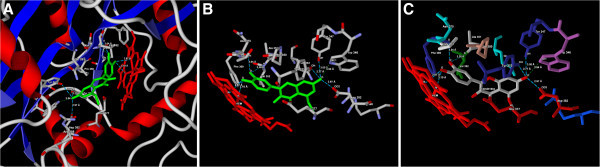

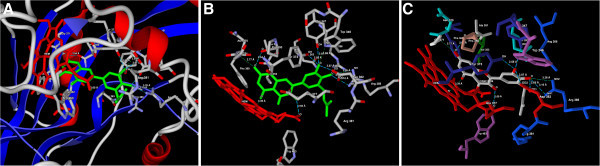

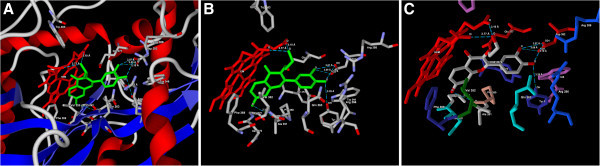

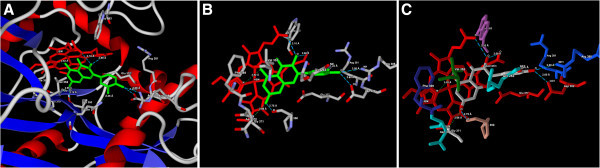

The top three docking hits showed common molecular interaction with Asp382, Tyr347 and HEM molecule. The snapshots of ligand-protein interaction and the binding mode for the top three docking hits (CID44610309, CID44259709, CID13964550) and quercetin is shown in Figure 1A,B,C, Figure 2A,B,C, Figure 3A,B,C and Figure 4A,B,C.

Figure 1.

(A) Predicted bonded interactions (green dashed lines) between CID5281604 (green) and Trp346, Tyr347, Val352, Phe369, Tyr373, Asp382 residues and HEM molecule of iNOS (B) binding mode of CID5281604 (green) to iNOS active site region (C) Binding mode representing the ligand based on atom type and the protein based on amino acid residue type colouring.

Figure 2.

(A) Predicted bonded interactions (green dashed lines) between CID5315126 (green) and Asp282, Trp346, Tyr347,Pro350, Gly371, Tyr373, Asp382, Arg388 residues and HEM molecule of iNOS (B) Binding mode of CID5315126 (green) to iNOS active site region (C) Binding mode representing the ligand based on atom type and the protein based on amino acid residue type colouring.

Figure 3.

(A) Predicted bonded interactions (green dashed lines) between CID9818879 (green) and Asp382, Tyr347, Pro350 residues and HEM molecule of iNOS (B) Binding mode of CID9818879 (green) to iNOS active site region (C) Binding mode representing the ligand based on atom type and the protein based on amino acid residue type colouring.

Figure 4.

(A) Predicted bonded interactions (green dashed lines) between quercetin (green) and Gln263, Pro350, Gly371 Asp382, Arg388 residue and HEM molecule of iNOS (B) Binding mode of quercetin (green) to iNOS active site region (C) Binding mode representing the ligand based on atom type and the protein based on amino acid residue type colouring.

The Lipinski rule of five parameters for the top docking hits and quercetin is shown in Table 3. Lipinski rule of five is a rule to evaluate drug likeness to determine if a chemical compound has a certain pharmacological or biological activity to make it an orally active drug in humans (Lipinski 2008; Lipinski et al. 1997). It is observed from Table 3, the hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) of quercetin is very low (only one HBA) compared to HBA of the top docking hits (6–8 HBA). The high number of HBA of the analogues could be an important factor and hence the analogues showed better binding affinity and molecular interaction with iNOS enzyme compared to quercetin. Additionally, the top docking hits have lower topological surface area (TPSA) values than quercetin suggesting that these compounds might have better oral bioavailability compared to quercetin (the oral bioavailability is inversely proportional to topological polar surface area) (Freitas 2006).

Table 3.

Lipinski rule of five filter including TPSA for the top poses

| SN | Compound ID | HBA | HBD | Mol. Wt. | XLog P3 | Rot B | TPSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5281604 | 7 | 4 | 316.26 | 1.3 | 2 | 116 |

| 2 | 5315126 | 7 | 5 | 370.35 | 3.5 | 3 | 127 |

| 3 | 9818879 | 7 | 4 | 330.29 | 1.6 | 4 | 116 |

| 4 | 5481966 | 7 | 5 | 370.35 | 4.1 | 3 | 127 |

| 5 | 5282154 | 8 | 5 | 332.26 | 1.5 | 2 | 137 |

| 6 | 13964550 | 6 | 3 | 300.26 | 1.2 | 2 | 96.2 |

| 7 | 5281691 | 7 | 4 | 316.26 | 1.9 | 2 | 116 |

| 8 | 11834044 | 7 | 4 | 316.26 | 2.5 | 2 | 116 |

| 9 | 6477685 | 6 | 4 | 312.27 | 2.0 | 2 | 107 |

| 10 | Quercetin | 1 | 5 | 302.23 | 1.5 | 1 | 127 |

ADME-toxicity analysis

The QuikProp (Schrödinger 2012) prediction for the top docking hits and quercetin is shown in Table 4. From Table 4, it is revealed that the top docking hits have MDCK cell permeability (QPPMDCK) in the acceptable range except for quercetin and CID9818879, the docked compounds are also in permissible range for IC50 value for blockage of HERG K+ channels (QPlogHERG), Caco-2 cell permeability (QPPCaco) and brain/blood partition coefficient (QPlogBB). More interestingly, the top docking hits showed higher human oral absorption (PercentHuman-OralAbsorption) ranging from 58.62% (CID5282154) to 69.077% (CID5481966) compared with 53.424% of quercetin.

Table 4.

ADME and pharmacological parameters prediction for the top docking hits using QikProp

| SN | CIDa | QPPMDCKb | QPlogHERGc | QPPCacod | Rule of 5e | QPlogBBf | PercentHuman- OralAbsorptiong | QPlogSh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5281604 | 46.45 | −5.78 | 112.076 | 0 | −1.997 | 62.147 | −2.657 |

| 2 | 5315126 | 39.535 | −5.519 | 96.549 | 0 | −2.035 | 67.901 | −3.821 |

| 3 | 9818879 | 15.081 | −5.291 | 39.584 | 0 | −2.253 | 59.194 | −2.99 |

| 4 | 5481966 | 44.662 | −5.886 | 108.08 | 0 | −2.08 | 69.077 | −4.04 |

| 5 | 5282154 | 33.312 | −4.486 | 82.401 | 0 | −1.817 | 58.62 | −1.669 |

| 6 | 13964550 | 41.929 | −6.124 | 101.947 | 0 | −2.086 | 64.314 | −3.349 |

| 7 | 5281691 | 63.477 | −4.866 | 149.622 | 0 | −1.572 | 66.37 | −2.045 |

| 8 | 11834044 | 43.054 | −4.535 | 104.474 | 0 | −1.543 | 61.02 | −1.685 |

| 9 | 6477685 | 45.568 | −4.337 | 110.106 | 0 | −1.605 | 64.219 | −1.197 |

| 10 | Quercetin | 20.486 | −4.032 | 52.551 | 0 | −1.754 | 53.424 | −1.169 |

aCompound I.D’s from NCBI PubChem database.

bPredicted apparent MDCK cell permeability in nm/s (acceptable range: <25 is poor, >500 is great).

cPredicted IC50 value for blockage of HERG K+ channels (concern below −7).

dPredicted Caco-2 cell permeability in nm/s (acceptable range: <25 is poor, <500 is great).

eNumber of violations of Lipinski’s rule of five (Lipinski et al. 1997; Bracket should be closed.

fPredicted brain/blood partition coefficient (Concern value is–3.0 to – 1.2).

gPredicted human oral absorption on 0 to 100% scale (acceptable range: <25% is poor, >80% is high).

hPredicted aqueous solubility, (Concern value is −6.5 to – 0.5).

Also, the top docking hits used in the present study does not violate Lipinski rule of five parameters. Lipinski rule of five is a rule to evaluate drug likeness to determine if a chemical compound has a certain pharmacological or biological activity to make it an orally active drug in human (Lipinski 2008; Lipinski et al. 1997). However, the rule does not predict whether a compound is pharmacologically active.

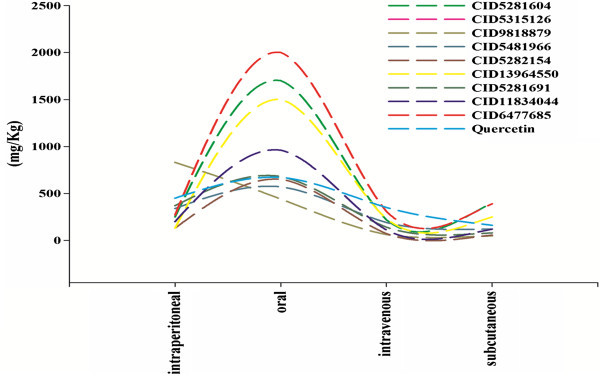

Again from the LD50 mouse and probability of health effects predictions for the top docking hits and quercetin using ACD/ I-Lab 2.0 (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc 1994) revealed the top docking hits have lower LD50 and lesser chance of health effects (shown in Table 5). The comparative analysis on the LD50 oral revealed CID11834044, CID13964550, CID5281604 and CID 6477685 have higher LD50 oral compared to quercetin (shown in Figure 5). Additionally, the comparative analysis on probability of health effects showed the top docking hits have more or less similar behaviour of health effects with quercetin except for CID5282154 and CID9818879 which showed chances of health effect on gastrointestinal system and lung (shown in Figure 6). In short, the top docked compounds could be lead molecule or a potential anti-cancer compound with enhanced pharmacological properties as compared to quercetin.

Table 5.

LD50and probability of health effects prediction for the docking hits and quercetin using ACD/ I-Lab 2.0

| ADME-Tox parameters | 5281604 | 5315126 | 9818879 | 5481966 | 5282154 | 13964550 | 5281691 | 11834044 | 6477685 | Quercetin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDa50 mouse (mg kg−1, intraperitoneal) | 250 | 340 | 830 | 340 | 130 | 130 | 370 | 200 | 270 | 450 |

| LDa50 mouse (mg kg−1, oral) | 1700 | 570 | 440 | 570 | 650 | 1500 | 680 | 960 | 2000 | 670 |

| LDa50 mouse (mg kg−1, intravenous) | 220 | 190 | 62 | 190 | 71 | 230 | 140 | 110 | 310 | 350 |

| LDa50 mouse (mg kg−1, subcutaneous) | 400 | 120 | 48 | 120 | 57 | 250 | 80 | 120 | 390 | 160 |

| Prob. of blood effectb | 0.3 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.9 | 0.33 | 0.3 | 0.78 | 0.29 | 0.34 |

| Prob. of cardiovascular system effectb | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.8 |

| Prob. of gastrointestinal system effectb | 0.68 | 0.78 | 1 | 0.78 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.72 |

| Prob. of kidney effectb | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.66 | 0.8 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| Prob. of liver effectb | 0.35 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.47 | 0.06 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.3 |

| Prob. of lung effectb | 0.37 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.38 |

a- Estimates LD50 value in mg/kg after intraperitoneal, oral, intravenous and subcutaneous administration to mice.

b- Estimates probability of blood, gastrointestinal system, kidney, liver and lung effect at therapeutic dose range.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis on LD50 mouse(intraperitoneal, oral, intravenous, subcutaneous) for Compound ID (5281604, 5315126, 9818879, 5481966, 5282154, 13964550, 5281691, 11834044, 6477685 and quercetin).

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis on probability of health effect on blood, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system, kidney, liver and lung for Compound ID (5281604, 5315126, 9818879, 5481966, 5282154, 13964550, 5281691, 11834044, 6477685 and quercetin).

Conclusions

The molecular docking studies with quercetin and its analogues into the binding cavity of iNOS inducible showed the analogues having more favourable interaction than quercetin with better rerank score, docking score, hydrogen bonding energy and ligand-protein interaction energy compared to quercetin. As earlier reported in literature, quercetin is known for having anti-cancer property and inhibiting the iNOS enzyme, the analogues docked at the binding cavity could have also possess some sort of anti-cancer property as it is 95% similar to quercetin retrived form the NCBI PubChem database. The docked compounds used in the present study do not violate the Lipinski rule of five parameters.

Also, from the ADME-Toxicity prediction using QikProp and ACD/ I-Lab 2.0 revealed the docked compounds are in the acceptable range of various pharmacological parameters and they have similar behaviour of health effects and LD50 compared to quercetin. Interestingly, the top dockings showed higher human oral absorption ranging from 58.62% (CID5282154) to 69.077% (CID5481966) compared with 53.424% of quercetin which is primary concern of this study as the clinical use of quercetin is limited by its low oral bioavailability.

Therefore we conclude that these compounds could be a potential lead molecule and supports for experimental testing against iNOS enzyme as anti cancer compounds.

Methods

Protein preparation

The three-dimensional crystal structure of human inducible nitric oxide synthase (PDB ID: 4NOS) was retrieved from the Protein Databank Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/). The coordinates of the dimeric crystallized iNOS is complexed with water molecules, iron protoporphyrin IX (heme), BH4, Zn+2 atom, ethylisothiourea and has a resolution of 2.25 Å. (Fischmann et al.1999). For molecular docking purpose, the dimeric molecule and iron protoporphyrin IX (heme) was loaded in the Molego Virtual Docker (MVD) and all the water molecules were removed.

Chemical similarity search

The 2D structure of quercetin (CID5280343) was retrieved from the NCBI PubChem database (Bolton et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2010) and performed a chemical structure search of quercetin at the NCBI PubChem database to retrieve the related compound and analogues. The search parameters were set at 95% similarity subjected to Lipinski rule of five filters (Lipinski et al. 1997; Lipinski 2008) resulting with 85 compounds.

The retrieved compounds were converted to three-dimensional format using the ChemOffice 2010 (ChemOffice 2010: CambridgeSoft Corporation) for docking purposes. The energy of these compound were optimized using MM2 force field methods (Ulrich and Norman 1982) and save as sybyl mol2 file format using ChemOffice 2010.

Computation

Potential ligand binding site for iNOS dimer (PDB ID: 4NOS) was predicted using MVD, having a volume of 678.91 Å3 and a surface area of 1245.44 Å2. The binding site was set inside a restriction sphere of radius 15 Å (X 0.28, Y 99.79, Z 8.70) using MVD.

The 85 analogues retrieved from the NCBI PubChem database were imported in the Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD). Bond flexibility of the compounds was set along and the side chain flexibility of the protein for the active site residues (Trp372, Glu377, Trp463, Phe476) was set with a tolerance of 1.10 and strength of 0.90 for docking simulations. RMSD threshold for multiple cluster poses was set at 2.00 Å. The docking algorithm was set at a maximum iteration of 1,500 with a simplex evolution size of 50 and a minimum of 10 runs were performed for each compound. The best pose of each compound was selected for the subsequent ligand–protein interaction energy analysis.

Molecular docking was carried out using Molegro Virtual Docker. MVD is based on a differential evolution algorithm; the solution of the algorithm considers the sum of the intermolecular interaction energy between the ligand and the protein and the intramolecular interaction energy of the ligand. The docking energy scoring function is based on the modified piecewise linear potential (PLP) with new hydrogen bonding and electrostatic terms included. Full description of the algorithm and its reliability compared to other common docking algorithm is described by Thomsen et al. (Thomsen and Christensen 2006).

ADME-toxicity prediction

ADME-Toxicity for the top docking hits and quercetin was predicted using QikProp (Schrödinger 2012). QikProp predicts physically significant descriptors and pharmaceutically relevant properties of organic molecules, either individually or in batches. QikProp provides ranges for comparing a particular molecule’s properties with those of 95% of known drugs. In the present study QikProp properties and descriptors such as apparent MDCK cell permeability (QPPMDCK), IC50 value for blockage of HERG K+ (QPlogHERG), Caco-2 cell permeability (QPPCaco), Lipinski rule of five (Lipinski et al. 1997; Lipinski 2008), brain/blood partition coefficient (QPlogBB), human oral absorption on 0 to 100% scale (Percent HumanOralAbsorption), aqueous solubility (QPlogS) for the top docking hits and quercetin was predicted to obtain the ADME properties of the compounds.

Additionally LD50 mouse and probability of health effects predictions for the top docking hits were calculated using ACD/ I-Lab 2.0 (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc 1994) which is a web-based service that provides instant access to spectral and chemical databases, and predicts properties including physicochemical, ADME, toxicity characteristics. Also a comparative analysis were performed for LD50 mouse (intraperitoneal, oral, intravenous, subcutaneous) and probability of health effect of blood, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system, kidney, liver and lung for the top docking hits.

Acknowledgement

SPS thanks Vice-Chancellor, Tezpur University, Assam, India for the necessary support.

Abbreviations

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthases

- iNOS

Inducible Nitric oxide synthase

- eNOS

Endothelium Nitric oxide synthases

- (nNOS)

Neurons Nitric oxide synthase

- CaM

Ca+2 –dependent calmodulin

- MVD

Moegro Virtual Docker

- ADME–Toxicity

Absorbtion distribution metabolism excretion and toxicity

- NCBI

National Centre for Biotechnology Information

- ACD

Advance Chemistry Development.

Footnotes

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author’s contribution

SPS carried out the molecular docking studies and ADME-toxicity analysis. SPS and BKK conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Salam Pradeep Singh, Email: salampradeep@gmail.com.

Bolin Kumar Konwar, Email: bkkon@tezu.ernet.in.

References

- Aaltoma SH, Lipponen PK, Kosma VM. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and its prognostic value in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3101–3106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaltomaa SH, Lipponen PK, Viitanen J, Kankkunen JP, Ala-Opas MY, Kosma VM. The prognostic value of inducible nitric oxide synthase in local prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2000;86:234–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACD/ I-Lab, Version 2.0. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ambs S, Merriam WG, Bennett WP, Felley-Bosco E, Ogunfusika MO, Oser SM, Klein S, Shields PG, Billiar TR, Harris CC. Frequent nitric oxide synthase-2 expression in human colon adenomas: implication for tumor angiogenesis and colon cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1998;58:334–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambs S, Merriam WG, Ogunfusika MO, Bennett WP, Ishibe N, Hussain SP, Tzeng EE, Geller DA, Billiar TR, Harris CC. p53 and vascular endothelial growth factor regulate tumor growth of NOS2-expressing human carcinoma cells. Nat Med. 1998;4:1371–1376. doi: 10.1038/3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambs S, Bennett WP, Merriam WG, Ogunfusika MO, Sean MO, Harrington AM, Shields PG, Felley-Bosco E, Hussain SP, Harris CC. Relationship between p53 mutations and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:86–88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton E, Wang Y, Thiessen PA, Bryant SH: PubChem: integrated platform of small molecules and biological activities. 4th edition. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC; 2008. [Annual reports in computational chemistry] chapt 12

- Brennan PA, Moncada S. From pollutant gas to biological messenger: the diverse actions of nitric oxide in cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:75–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ChemOffice CambridgeSoft Corporation, 875 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA; 2010.

- Chen YC, Shen SC, Lee WR, Hou WC, Yang LL, Lee TJ. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors and lipopolysaccharide induced inducible NOS and cyclooxygenase-2 gene expressions by rutin, quercetin, and quercetin pentaacetate in RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Cell Biochem. 2001;82:537–548. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Xie QW, Calaycay J, Mumford RA, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Nathan C. Calmodulin is a subunit of nitric oxide synthase from macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;176:599–604. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell JA, Steele VE, Sigman CC, Fay JR. Is inducible nitric oxide synthase a target for chemoprevention? Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:815–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischmann TO, Hruza A, Niu XD, Fossetta JD, Lunn CA, Dolphin E, Prongay AJ, Reichert P, Lundell DJ, Narula SK, Weber PC. Structural characterization of nitric oxide synthase isoforms reveals striking active-site conservation. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:233–242. doi: 10.1038/6675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester K, Ambs S, Lupold SE, Kapust RB, Spillare EA, Weinberg WC, Felley-Bosco E, Wang XW, Geller DA, Tzeng E, Billiar TR, Harris CC. Nitric oxide-induced p53 accumulation and regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by wild-type p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2442–2447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi A, Gallo O, Paglierani M, Sardi I, Magnelli L, Masini E, Santucci M. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in laryngeal neoplasia: correlation with angiogenesis. Head Neck. 2002;24:16–23. doi: 10.1002/hed.10045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas MP. MIA-QSAR modelling of anti-HIV-1 activities of some 2-amino-6-arylsulfonylbenzonitriles and their thio and sulfinyl congeners. Org Biomol Chem. 2006;4:1154–1159. doi: 10.1039/b516396j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo O, Masini E, Morbidelli L, Franchi A, Fini-Storchi I, Vergari WA, Ziche M. Role of nitric oxide in angiogenesis and tumor progression in head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:587–596. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.8.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Mediavilla V, Crespo I, Collado PS, Esteller A, Sánchez-Campos S, Tuñón MJ, González-Gallego J. The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J, Boulton CL. Nitric oxide signaling in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:683–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlhaar DK, Verkhivker G, Rejto PA, Fogel DB, Fogel LJ, Freer ST. Docking Conformationally Flexible Small Molecules Into a Protein Binding Site Through Evolutionary Programming. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Evolutionary Programming. Lect Notes Comput Sci. 1995;1447:449–461. doi: 10.1007/BFb0040797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlhaar DK, Bouzida D, Rejto PA. Fully Automated And Rapid Flexible Docking of Inhibitors Covalently Bound to Serine Proteases. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Evolutionary Programming. London, UK: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh DK, Crane BR, Ghosh S, Wolan D, Gachhui R, Crooks C, Presta A, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED, Stuehr DJ. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: role of the N-terminal beta-hairpin hook and pterin-binding segment in dimerization and tetrahydrobiopterin interaction. EMBO J. 1999;18:6260–6270. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JE, Hofseth LJ, Hussain SP, Harris CC. Nitric oxide and p53 in cancer-prone chronic inflammation and oxyradical overload disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:3–9. doi: 10.1002/em.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith OW, Stuehr DJ. Nitric oxide synthases: properties and catalytic mechanism. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:707–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao XP, Pretlow TG, Rao JS, Pretlow TP. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is expressed similarly in multiple aberrant crypt foci and colorectal tumors from the same patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:419–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Kuwahara M, Fujisaki N, Furihata M, Ohtsuki Y, Kagawa S. Immunohistochemical findings of nitric oxide synthase expression in urothelial transitional cell carcinoma including dysplasia. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:1275–1279. doi: 10.3892/or.8.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey MJ, Granger DN, Kubes P. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and regulation of leucocyte/endothelial cell interactions: studies in iNOS-deficient mice. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173:119–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A, Crowell VES, Caroline CS, Judith RF. Is inducible nitric oxide synthase a target for chemoprevention? Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:815–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinaci MK, Erkasap N, Kucuk A, Koken T, Tosun M. Effects of quercetin on apoptosis, NF-κB and NOS gene expression in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Exp Ther Med. 2012;3:249–254. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298:249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Morisaki T, Tsukahara Y, Uchiyama A, Matsunari Y, Mibu R, Tanaka M. Nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in human colon carcinoma tissue. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70:222–229. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199904)70:4<222::AID-JSO5>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J Pharm Toxicol Methods. 2008;44:235–249. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1997;23:3–25. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lirk P, Hoffmann G, Rieder J. Inducible nitric oxide synthase–time for reappraisal. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2002;1:89–108. doi: 10.2174/1568010023344913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking J, Xie QW, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–350. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marletta MA, Hurshman AR, Rusche KM. Catalysis by nitric oxide synthase. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;2:656–663. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(98)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrogi AJ, Travis WD, Welsh JA, Khan MA, Rahim H, Tazelaar H, Pairolero P, Trastek V, Jett J, Caporaso NE, Liotta LA, Harris CC. Nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase 2, and vascular endothelial growth factor in the angiogenesis of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4739–4744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massi D, Franchi A, Sardi I, Magnelli L, Paglierani M, Borgognoni L, Maria Reali U, Santucci M. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in benign and malignant cutaneous melanocytic lesions. J Pathol. 2001;194:194–200. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200106)194:2<194::AID-PATH851>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messmer UK, Ankarcrona M, Nicotera P, Brüne B. p53 expression in nitric oxide-induced apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 1994;355:23–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michal G. Biochemical pathways. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Michel T, Feron O. Nitric oxide synthases: which, where, how, and why? J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2146–2152. doi: 10.1172/JCI119750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molegro APS. MVD 5.0 Molegro Virtual Docker. Denmark: DK-8000 Aarhus C; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami A, Ashida H, Terao J. Multitargeted cancer prevention by quercetin. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Deng Z, Wang C. Preparation and prodrug studies of quercetin pentabenzensulfonate. Yakugaku Zasshi. 2008;128:1845–1849. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.128.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao CV. Nitric oxide signaling in colon cancer chemoprevention. Mutat Res. 2004;555:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raso GM, Meli R, Di Carlo G, Pacilio M, Di Carlo R. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression by flavonoids in macrophage J774A.1. Life Sci. 2001;68:921–931. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00999-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietjens IM, Boersma MG, van der Woude H, Jeurissen SM, Schutte ME, Alink GM. Flavonoids and alkenylbenzenes: mechanisms of mutagenic action and carcinogenic risk. Mutat Res. 2005;574:124–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropponen KM, Kellokoski JK, Lipponen PK, Eskelinen MJ, Alanne L, Alhava EM, Kosma VM. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in colorectal cancer and its association with prognosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;11:1204–1211. doi: 10.1080/003655200750056709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandau K, Pfeilschifter J, Brüne B. The balance between nitric oxide and superoxide determines apoptotic and necrotic death of rat mesangial cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:4938–4946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger LLC. QikProp, version 3.5. NY: New York; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Swana HS, Smith SD, Perrotta PL, Saito N, Wheeler MA, Weiss RM. Inducible nitric oxide synthase with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 1999;161:630–634. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)61985-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen R, Christensen MH. MolDock: a new technique for high-accuracy molecular docking. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3315–3321. doi: 10.1021/jm051197e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen LL, Lawton FG, Knowles RG, Beesley JE, Riveros-Moreno V, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthase activity in human gynecological cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1352–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen LL, Miles DW, Happerfield L, Bobrow LG, Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthase activity in human breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:41–44. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich B, Norman LA. Molecular mechanics (ACS Monograph 177) Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Uotila P, Valve E, Martikainen P, Nevalainen M, Nurmi M, Härkönen P. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase-2 in human prostate cancer. Urol Res. 2001;29:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s002400000148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakkala M, Kahlos K, Lakari E, Pääkkö P, Kinnula V, Soini Y. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, apoptosis, and angiogenesis in in situ and invasive breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2408–2416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Woude H, Alink GM, van Rossum BE, Walle K, van Steeg H, Walle T, Rietjens IM. Formation of transient covalent protein and DNA adducts by quercetin in cells with and without oxidative enzyme activity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1907–1916. doi: 10.1021/tx050201m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verschoyle RD, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Putative cancer chemopreventive agents of dietary origin-how safe are they? Nature Cancer. 2007;59:152–162. doi: 10.1080/01635580701458186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Bolton E, Dracheva S, Karapetyan K, Shoemaker SA, Suzek TO, Wang J, Xiao J, Zhang J, Bryant SH. An overview of the PubChem BioAssay resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D255–D266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiming X, Li ZL, Marilena L, Mohamed A, Ian GC. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell Res. 2002;12:311–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Charles IG, Moncada S, Gorman P, Sheer D, Liu L, Emson P. Mapping of the genes encoding human inducible and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS2 and NOS3) to the pericentric region of chromosome 17 and to chromosome 7, respectively. Genomics. 1994;21:419–422. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagihashi N, Kasajima H, Sugai S, Matsumoto K, Ebina Y, Morita T, Murakami T, Yagihashi S. Increased in situ expression of nitric oxide synthase in human colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:109–114. doi: 10.1007/PL00008208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JM, Chen CC. GEMDOCK: a generic evolutionary method for molecular docking. Proteins. 2004;55:288–304. doi: 10.1002/prot.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]