Abstract

Paramolar is a supernumerary molar usually small and rudimentary, most commonly situated buccally or palatally to one of the maxillary molars. Paramolar is a developmental anomaly and has been argued to arise from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Reports of this entity are rarely found in the dental literature. This article presents a case report of an unusual occurrence of a paramolar in the maxilla in otherwise a healthy individual. In addition, literature review, prevalence, classification, etiology, complications, diagnosis, and therapeutic strategies that may be adopted when supernumeraries occurs have been discussed.

Keywords: Extra molar, paramolar, paramolar tubercle, parastyle, supernumerary teeth

INTRODUCTION

Supernumerary teeth, or hyperdontia, is an odontostomatologic anomaly and may be defined as any teeth or tooth substance in excess of the usual configuration of 20 deciduous, and 32 permanent teeth.[1] Supernumerary teeth may occur singly, multiply, unilaterally or bilaterally, erupted or impacted, in one or both jaws, and in the deciduous as well as in permanent dentition. The reported prevalence of supernumerary teeth in the permanent dentition ranges from 0.1% to 3.8% and from 0.3% to 0.6% in the deciduous dentition.[2] In permanent dentition, supernumerary teeth are more frequent in males than in females, with a proportion of 2:1.[3] But this sexual dismorphism is not observed in the deciduous dentition.[4] It also seems that Asian populations are more affected with supernumeraries than others.[5–7] Single supernumeraries occur in 76-86% of cases, double supernumeraries in 12-23% of cases, and multiple supernumeraries in less than 1% of cases.[3,5,6,8,9] Multiple hyperdontia is rare in individuals with no other associated diseases or syndromes. The presence of multiple supernumerary teeth may be part of developmental disorders such as Cleft lip and palate, Cleidocranial dysostosis, Gardner's syndrome, Fabry–Anderson's syndrome, Ellis–Van Creveld syndrome (Chondroectodermal dysplasia), Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, Incontinentia Pigmenti, and Tricho–Rhino–Phalangeal syndrome.[3]

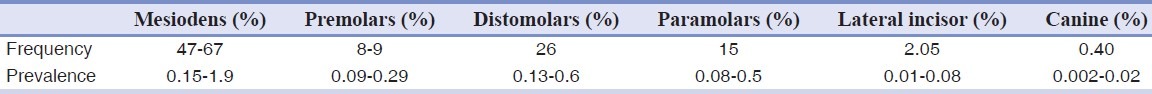

Supernumerary teeth can be found in almost any region of the dental arch.[10] These teeth have a striking predilection for maxilla over mandible. They are most frequently located in the maxilla, the anterior medial region, where 80% of all supernumerary teeth are found. More rarely, they can be located in the superior distomolar zone, inferior premolar, superior premolar, inferior distomolar, superior canine zone, and inferior incisor.[11] Table 1 demonstrates the prevalence and frequency of supernumerary teeth.[5,12,13]

Table 1.

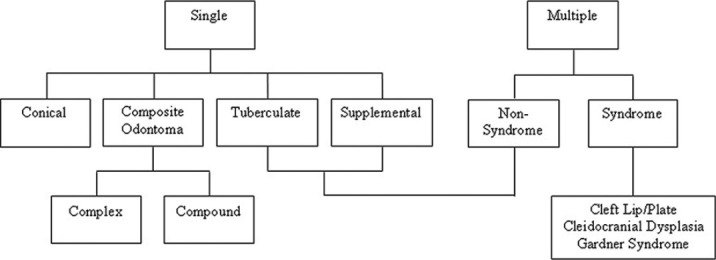

The crowns of supernumerary teeth may show either a normal appearance or different atypical shapes and their roots may be completely or incompletely developed.[10] Supernumerary teeth are classified according to their position in the dental arch or their morphological form[14] [Figure 1]. Positional variations include mesiodens, paramolars, distomolars, and parapremolars. A mesioden is a typical conical supernumerary tooth located between the maxillary central incisors; a paramolar is a supernumerary molar usually small and rudimentary, situated buccally or palatally to one of the maxillary molars or most commonly occurs in the interproximal space buccal to the upper second and third molars; a distomolar is a fourth permanent molar, which is usually placed either directly distal or distolingual to the third molar; and a parapremolar most commonly occurs in the interproximal space buccal to the upper first and second premolars. Variation in morphological form consists of conical types, tuberculated types, supplemental teeth, and odontomes. A conical supernumerary tooth is small, peg-shaped (coniform) tooth with normal root; a tuberculate (multicusped) supernumerary tooth is short, barrel-shaped tooth with normal appearing crown, or invaginated but rudimentary root. A supplemental supernumerary tooth resembled one of the normal series of tooth (duplication) and found at the end of a tooth series. Most of the supernumerary teeth in the deciduous dentition are of the supplemental type and seldom remain impacted and an odontome type having no regular shape. Odontome refers to any tumor of odontogenic origin. Most authorities, however, accept the view that the odontome represents a hamartomatous malformation rather than a neoplasm. Complex composite odontome and compound composite odontome are the two separate types of odontomes that have been described.[10] Complex composite odontome refers to the diffuse mass of dental tissue, which is totally disorganized, whereas compound composite odontome refers to the malformation, which bears some superficial anatomical similarity to a normal tooth.

Figure 1.

Classification of supernumerary teeth

According to their shape, supernumerary teeth are classified as supplemental (eumorphic) and rudimentary (dysmorphic).[15] If the supernumerary teeth present a normal morphology, it is denoted as “supplemental” if they presented morphologic and volumetric anomalies they are referred to as rudimentary. The supernumerary teeth position can be recorded as ‘between central incisors’ and ‘overlap’ and its orientation can be described as ‘vertical’, ‘inverted’, and ‘transverse’.[16]

This article presents a case report of an unusual occurrence of a paramolar in the maxilla in otherwise a healthy individual. In addition, literature review, prevalence, classification, etiology, complications, diagnosis, and therapeutic strategies that may be adopted when supernumeraries occurs have been discussed.

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old male patient was referred to the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with a chief complaint of pain in his upper left back region of the mouth. Patient's medical and familial history was noncontributory and there was no sign of any systemic diseases or syndromes.

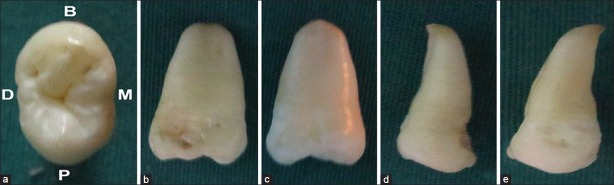

An intraoral examination revealed a Class I dentition with a well aligned upper and lower arch. In addition to the full complement of permanent teeth, there was an extra tooth present palatally between the maxillary left first and second molars [Figure 2]. This supernumerary tooth was diagnosed as a paramolar. The crown of this paramolar had two cusps and quite resembled a permanent premolar. The tooth was rotated, with its buccal surface face distally, whereas its mesial surface faced buccally. On clinical examination, caries was detected on the mesial surface of the paramolar [Figure 3]. Soft tissue examination revealed inflammation in the surrounding periodontium between the maxillary left first and second molars and paramolar.

Figure 2.

Intraoral photograph showing paramolar between maxillary left first and second molar

Figure 3.

Clinical images of extracted paramolar viewed from (a) occlusal, (b) mesial, (c) distal, (d) buccal, and (e) palatal surface

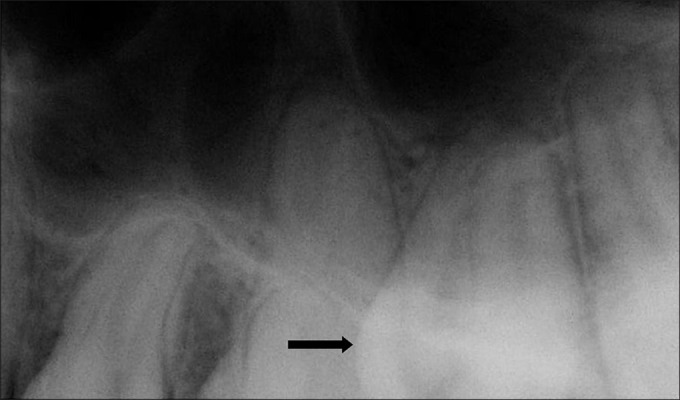

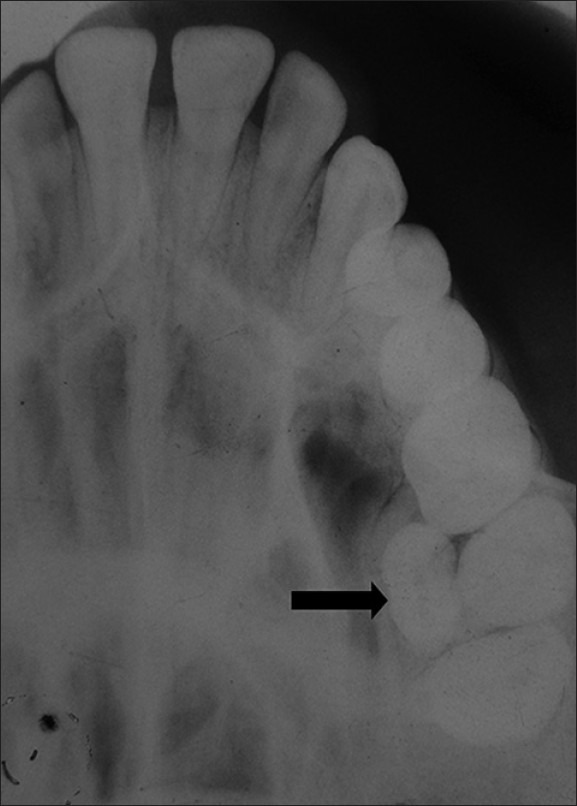

Following clinical examination, panoramic, periapical, and occlusal radiographs were taken. The palatally positioned paramolar made its clear visual assessment with the panoramic radiograph difficult. Periapical and occlusal radiographs revealed the presence of a supernumerary tooth with a single root [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Periapical radiograph showing paramolar with fully formed root (arrow)

Figure 5.

Maxillary cross sectional occlusal radiograph showing erupted paramolar (arrow)

The patient was informed of the existing condition and extraction of the paramolar was advised as maintenance of oral hygiene in this area was difficult and there was the possibility of food lodgement, recurrence of dental caries, and deterioration of the surrounding periodontal health. The patient was referred to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery for extraction of his paramolar.

The extracted tooth was cleaned, disinfected, and analyzed. The tooth had a normal morphology. The length of the root was normal relative to its crown. The root apex was completely developed. Radiographic investigation revealed a Vertucci's Type I canal configuration. The actual size of the tooth was measured with a caliper. The mesiodistal and buccopalatal width of the crown was 6 and 10 mm, respectively. The length of the crown was 6.5 mm, whereas the length of the root was 12 mm. The morphometric measurements displayed that the paramolar had very close values relative to the maxillary premolar [Figure 3].

DISCUSSION

The occurrence of paramolar is relatively uncommon. The exact etiology of this anomaly is still not completely understood. Several theories have been suggested for their occurrence such as the ‘phylogenetic theory’,[17] the ‘dichotomy theory,’[18] a hyperactive dental lamina,[15,19] and a combination of genetic and environmental factors-unified etiologic explanation.[19]

The ‘phylogenetic theory’ relates to the phylogenetic process of atavism (evolutionary throwback), which has been suggested. Hyperdontia is the result of the reversional phenomenon or atavism. Atavism is the return to or the reappearance of an ancestral condition or type. In past centuries, the third molar was rarely absent in the primitive dentition; it was comparable in size to the second molar and a fourth molar was often present. Phylogenetic evolution has resulted in a gradual reduction in dimensions of the dental arches, which in turn resulted in a decrease in both the number as well as the size of man's teeth, causing greater development of the neurocranium than the splanchnocranium. Hence, a supernumerary paramolars may be an atavistic appearance of the fourth molar of the primitive dentition.[17] This theory has been rejected by many authors. The ‘dichotomy theory’ is where a supernumerary tooth such as a paramolar is created as a result of dichotomy of the tooth bud. The supernumerary tooth may develop from the complete splitting of tooth bud.[18] The tooth bud splits into two equal or different-sized parts resulting in two teeth of equal size or one normal and one dysmorphic tooth, respectively.

A hyperactive dental lamina where the localized and independent hyperactivity of dental lamina is the most accepted cause for the development of the supernumerary tooth. It is suggested that paramolars are formed as a result of local, independent, conditioned hyperactivity of the dental lamina.[15,19] According to this theory, the lingual extension of an additional tooth bud leads to a eumorphic tooth, whereas the rudimentary form arises from proliferation of epithelial remnants of the dental lamina induced by pressure of the complete dentition.[20] While others tend to believe that hyperdontia is a disorder with pattern of multifactorial inheritance originating from hyperactivity of dental lamina. Remnants of the dental lamina can persist as epithelial pearls or islands, “rests of Serres” within the jaw. If the epithelial remnants are subjected to initiation by induction factors, an extra tooth bud is formed resulting in the development of either a supernumerary tooth or odontome.[21] The most accredited theory sustains that teeth in excess of the normal number are of a combination of genetic and environmental factors-unified etiologic explanation.[19] This could be explained by the presence of supernumerary teeth in the relatives of subjects affected with this dental anomaly. The hereditary trait does not exhibit a simple Mendelian pattern. This may be probably due to the low penetrance of dominant autosomal transmission, which implies that some generations are not affected by the disorder. However, although the literature points to a familial predisposition to hyperdontia, in our case there was no such relationship noticed in any of the direct relatives of the patient.

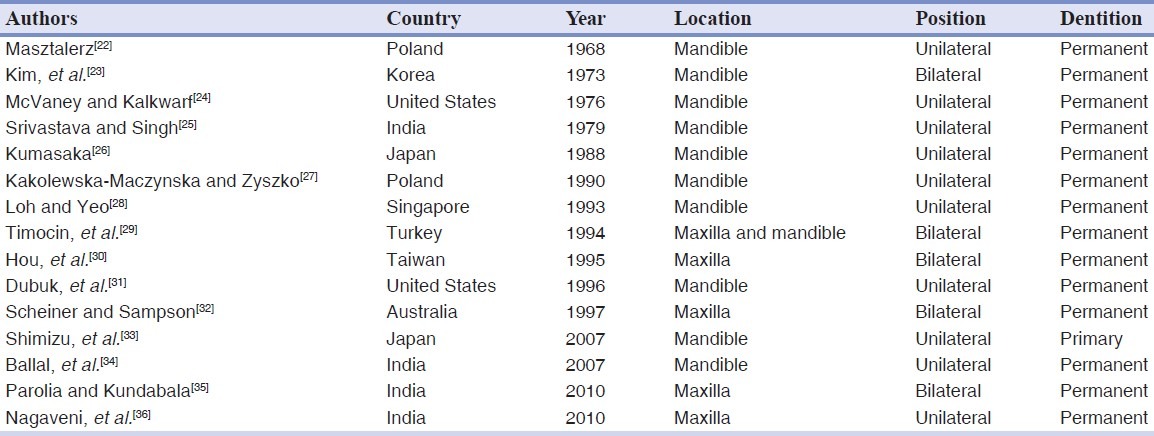

Extensive literature review in Medline revealed very few reported cases of paramolars [Table 2].[22–36] Paramolars are less often seen in maxilla,[29,30,32,35] rarely bilateral,[23,30,32,35,36] extremely rare in primary dentition and only one such case has been reported.[33] They are usually rudimentary, mostly situated buccally between the second and third molars, whereas in very rare cases they can be found between the first and second molars.[35,36] Fusion of the paramolar with their normal counterpart is also extremely rare. A case of endodontic management of fused mandibular left second molar with paramolar[34] and paramolar with bifid crown[28] has been reported.

Table 2.

Reported cases of paramolar tooth: A literature review

During diagnosis, it is also necessary to differentiate and rule out other structures that may occur in the molar region like a paramolar tubercle or a fused supernumerary tooth. Bolk, in 1916, was the first to describe an additional cusp occurring on the buccal surfaces of upper and lower permanent molars, which he named as paramolar tubercle.[37] Dahlberg in 1945 suggested that paramolar cusp is a term applied to any stylar or anomalous cusps, supernumerary inclusion or eminence occurring on the buccal surfaces of both upper and lower premolars and molars. He introduced paleontologic nomenclature when he referred to this structure as “protostylid” if present in the lower molars and “parastyle” when present in the upper molars.[38] It is well accepted today that this structure is a derivative of cingulum and variable in its delineation. This structure is usually expressed on the buccal surface of the mesiobuccal cusp (paracone) and rarely on the distobuccal cusp (metacone). Its significance is unknown but it is reported that as paramolar tubercles arise from the buccal cingulum, these structures in human dentition probably represent the remnants of the cingulum of mammals and the lower primates.

Supernumerary teeth may erupt normally, remain impacted, appear inverted, or assume an abnormal path of eruption. Supernumerary teeth with a normal orientation will usually erupt. However, only 13-34% of all permanent supernumerary teeth erupts normally as compared with 73% of primary supernumerary teeth.[3] The rest remain unerupted and may produce complications.

If complications arise, they may include prevention or delayed eruption of associated permanent teeth; retention or ectopic eruption of adjacent teeth; displacement, or rotation of adjacent teeth; crowding due to insufficient space for the eruption of other teeth; malocclusion due to a diminution of space in the dental arch when the paramolar erupts; interdental spacing between molars; traumatic bite when buccally positioned paramolar causes laceration of the buccal mucosa; interference during orthodontic treatment; dilaceration or delayed or abnormal root development of associated permanent teeth; follicular cyst formation from the degeneration of the follicular sac of the supernumerary tooth; neoplasm; trigeminal neuralgia when the paramolar compresses the nerve, pulp necrosis, and root resorption of adjacent tooth due to the pressure exerted by the paramolar tooth;[31] dental caries due to plaque retention in inaccessible areas; and gingival inflammation and localized periodontitis in the surrounding soft tissues.[30,35] As seen in our case, the presence of paramolar resulted in its decay due to plaque retention and inflammation in the surrounding periodontium.

Most supernumerary teeth are impacted and usually are discovered by chance during radiographic examination with no associated complications. However, if patients reports with complications that are usually associated with the presence of supernumerary teeth, the clinician should be alert of the possible presence of supernumerary teeth and should advocate appropriate radiographic investigation.

The most useful radiographic investigation is the rotational tomograph (OPG), with additional views of the anterior maxilla and mandible, in the form of occlusal or periapical radiographs. If concerns are present regarding the possibility of root resorption of a permanent tooth caused by a supernumerary tooth, then long-cone periapical radiographs will be required for diagnosis. In order to localize an unerupted supernumerary or normal tooth, the use of vertical or horizontal parallax technique is recommended.[39] Parallax is the apparent movement of an object against a background, caused by a change in observers position. This can be achieved with two separate radiographs taken at different angles, but showing the same region. When using this technique, the reference point is usually the root of an adjacent tooth. The image of the tooth that is further away from the X-ray tube head will move in the same direction as the tube head; the image of the tooth that is closer will move in the opposite direction. In addition, cone-beam computed tomography has recently been used to evaluate ST.[40] This technique yields detailed three dimensional images of local structures and proves useful in pretreatment evaluation of ST and surrounding structures.

The clinical management of patients with paramolar usually depends upon the position of the paramolar and on its effect or potential effect on adjacent teeth and important anatomical structures. Treatment options for paramolar as like any other supernumerary teeth may include observation or extraction. Observation involves no treatment other than monitoring the patient clinically and radiographically. This is true if the paramolar is asymptomatic and is not causing any problem. If any of the aforementioned complications are evident, it is advisable to extract the paramolar. In our case, extraction of the carious paramolar was carried out to facilitate good oral hygiene maintenance so as to prevent the recurrence of dental caries and to maintain surrounding periodontal health.

CONCLUSION

A clinician must be aware of the various types of supernumerary teeth and should recognize signs suggestive of their presence. One should perform required investigations when these conditions are suspected and upon diagnosis each case should be managed appropriately in order to minimize complication.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Schulze C. Developmental abnormalities of the teeth and jaws. In: Gorlin RJ, Goldman HM, editors. Thoma's oral pathology. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1970. pp. 112–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Díaz A, Orozco J, Fonseca M. Multiple hyperodontia: Report of a case with 17 supernumerary teeth with non syndromic association. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:E229–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajab LD, Hamdan MA. Supernumerary teeth: Review of the literature and a survey of 152 cases. Int J Paed Dent. 2002;12:244–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinirons MJ. Unerupted premaxillary supernumerary teeth: A study of its occurrence in males and females. Br Dent J. 1982;153:110. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu JF, Marcushamer M, King LD, Henry RJ. Supernumerary and congenitally absent teeth: A literature review. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1996;20:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.So LL. Unusual supernumerary teeth. Angle Orthod. 1990;60:289–92. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1990)060<0289:UST>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore SR, Wilson DF, Kibble J. Sequential development of multiple supernumerary teeth in the mandibular premolar region-a radiographic case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:143–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2002.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenzweig KA, Garbarski O. Numerical aberrations in the permanent teeth of grade school children in Jerusalem. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1965;23:277–83. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330230315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solares R, Romero MI. Supernumerary premolars: A literature review. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:450–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garvey MT, Barry HJ, Blake M. Supernumerary teeth an overview of the classification, diagnosis and treatment. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:612–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leco Berrocal MI, Martín Morales JF, Martínez González JM. An observational study of the frequency of supernumerary teeth in a population of 2000 patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12:E134–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gay Escoda C, Mateos Micas M, España Tost A, Gargallo Albiol J. Otras inclusiones dentarias. Mesiodens y otros dientes supernumerarios. In: Gay Escoda C, de Cirugía Bucal Aytés Berini L. Tratado, Tomo I, editors. Dientes temporales supernumerarios. Dientes temporales incluidos. 1st ed. Madrid: Ergon; 2004. pp. 497–534. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stafne E. Supernumerary teeth. Dent Cosmos. 1932;74:653–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell L. Supernumerary teeth. Dent Update. 1989;16:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primosch RE. Anterior supernumerary teeth – assessment and surgical intervention in children. Pediatr Dent. 1981;3:204–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregg TA, Kinirons MJ. The effect of the position and orientation of unerupted premaxillary supernumerary teeth on eruption and displacement of permanent incisors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1991;1:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1991.tb00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith JD. Hyperdontia: Report of a case. J Am Dent Assoc. 1969;79:1191–2. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1969.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu JF. Characteristics of premaxillary supernumerary teeth: A survey of 112 cases. ASDC J Dent Child. 1995;62:262–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook AH. A unifying etiological explanation for anomalies of human tooth number and size. Archs Oral Biol. 1984;29:373–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sykaras SN. Mesiodens in primary and permanent dentitions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;39:870–4. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hattab FN, Yassin OM, Rawashdeh MA. Supernumerary teeth: Report of three cases and review of the literature. ASDC J Dent Child. 1994;61:382–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masztalerz A. Paramolar teeth. Czas Stomatol. 1968;21:249–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HS, Song YH, Lee YS, Park KM. A case of bilateral paramolar teeth. Taehan Chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi. 1973;11:131–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McVaney TP, Kalkwarf KL. Misdiagnosis of an impacted supernumerary tooth from a panographic radiograph. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41:678–81. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Srivastava RP, Singh G. Mandibular paramolar. Uttar Pradesh State Dent J. 1979;10:109–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumasaka S, Hideshima K, Shinji H, Higasa R, Kubota M, Uchimura N. A case of two impacted paramolar in lower right molar dentition. Kangawa Shigaku. 1988;23:417–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakolewska–Maczyńska J, Zyszko A. Paramolar and distomolar teeth. Czas Stomatol. 1990;43:232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh FC, Yeo JF. Paramolar with bifid crown. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:257–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90216-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timocin N, Yalcin S, Ozgen M, Tanyeri H. Supernumerary Molars and Paramolars, A Case Report. J Nihon Univ Sch Dent. 1994;36:145–50. doi: 10.2334/josnusd1959.36.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou GL, Lin CC, Tsai CC. Ectopic supernumerary teeth as a predisposing cause in localized periodontitis. Case report. Aust Dent J. 1995;40:226–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1995.tb04799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubuk AN, Selvig KA, Tellefsen G, Wikesjö UM. Atypically located paramolar. Report of a rare case. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104:138–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheiner MA, Sampson WJ. Supernumerary teeth: A review of literature and four case reports. Aust Dent J. 1997;42:160–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu T, Miyamoto M, Arai Y, Maeda T. Supernumerary tooth in the primary molar region: A case report. J Dent Child (Chic) 2007;74:151–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballal S, Sachdeva GS, Kandaswamy D. Endodontic management of a fused mandibular second molar and paramolar with the aid of spiral computed tomography: A case report. J Endod. 2007;33:1247–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parolia A, Kundabala M. Bilateral Maxillary Paramolars and Endodontic Therapy: A Rare Case Report. J Dent (Tehran) 2010;7:107–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagaveni NB, Umashankara KV, Radhika NB, Reddy PB, Manjunath S. Maxillary paramolar: Report of a case and literature review. Arch Orofac Sci. 2010;5:24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolk L. Problems of Human Dentition. Am J Anat. 1916;19:91. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahlberg AA. The Paramolar Tubercle (Bolk) Am J Phys Anthropol. 1945;32:97. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houston WJ, Stephens CD, Tulley WJ. A Textbook of Orthodontics. 2nd ed. Atlanta, Georgia: Wright Publications; 1992. pp. 174–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu DG, Zhang WL, Zhang ZY, Wu YT, Ma XC. Three dimensional evaluations of supernumerary teeth using cone-beam computed tomography for 487 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:403–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]