Abstract

Background

Current standard therapy for patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) consists of anticoagulant therapy and graduated elastic compression stockings. Despite use of this strategy, the post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS) develops frequently, causes substantial patient disability, and impairs quality of life (QOL). Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis (PCDT), which rapidly removes acute venous thrombus, may reduce the frequency of PTS. However, this hypothesis has not been tested in a large multicenter randomized trial.

Study Design

The ATTRACT Study is an ongoing NIH-sponsored, Phase III, multicenter, randomized, open-label, assessor-blinded, parallel two-arm, controlled clinical trial. Approximately 692 patients with acute proximal DVT involving the femoral, common femoral, and/or iliac vein are being randomized to receive PCDT + standard therapy versus standard therapy alone. The primary study hypothesis is that PCDT will reduce the proportion of patients who develop PTS within 2 years by one-third, assessed using the Villalta Scale. Secondary outcomes include safety, general and venous disease-specific QOL, relief of early pain and swelling, and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion

ATTRACT will determine if PCDT should be routinely used to prevent PTS in patients with symptomatic proximal DVT above the popliteal vein.

Introduction

The Post-Thrombotic Syndrome (PTS) develops in approximately 40% of patients within two years after a first episode of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (1). Clinical manifestations of PTS commonly include chronic pain, swelling, heaviness, and/or fatigue of the affected limb. Patients with advanced PTS can develop venous claudication, stasis dermatitis, subcutaneous fibrosis, and skin ulceration. PTS impairs quality of life (QOL) significantly and imposes a major economic burden upon patients, healthcare providers, and society (2,3).

Anticoagulant drugs, the standard treatment for DVT, prevent pulmonary embolism (PE) and thrombus extension but do not actively remove venous thrombus (4). Because the persistence of thrombus within the venous system has been linked to the development of PTS, it is hypothesized that early, active elimination of venous thrombus in DVT patients may prevent PTS. This “Open Vein Hypothesis” is supported by: (a) studies linking poor thrombus clearance to venous valve dysfunction and recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) (5,6); (b) studies finding an association between residual venous thrombus or valve incompetence and PTS (7); and (c) clinical trials suggesting that systemic thrombolysis, surgical thrombectomy, or catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) reduces PTS (8–11).

Pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis (PCDT) refers to catheter-directed administration of a fibrinolytic drug directly into the venous thrombus, with concomitant use of catheter-based device(s) to macerate the thrombus and speed thrombus removal (12). PCDT is currently used as a second-line treatment for DVT that progresses despite anticoagulation. However, the first-line use of PCDT for PTS prevention is controversial because, without evidence from a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT), it is uncertain if PCDT reduces clinically-important PTS with acceptable safety and cost-effectiveness. The need for such a RCT has been endorsed by multidisciplinary expert panels and the U.S. Surgeon General (13). We therefore developed the Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal with Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis (ATTRACT) Trial to address this controversy.

Study Objectives

The primary study objective is to determine if the initial use of PCDT along with standard DVT therapy reduces the proportion of patients who develop PTS during 24 months of follow-up compared with standard DVT therapy alone in patients with symptomatic acute proximal DVT. Secondary objectives include: (a) comparing the proportions of patients who develop major bleeding, symptomatic VTE, and death; venous disease-specific and general QOL; and relief of acute DVT symptoms between the two treatment arms; (b) identifying pre-treatment predictors of therapeutic response to PCDT in the prevention of PTS; (c) comparing the short-term and long-term medical care costs of treatment and evaluating the incremental cost-effectiveness of PCDT compared with standard therapy alone; and d) determining the post-treatment anatomic/physiologic conditions that need to be achieved (i.e. removal of thrombus, restoration of venous patency, prevention of valvular incompetence) to prevent PTS.

Study Design, Organization, and Regulatory Status

ATTRACT is an ongoing, investigator-initiated, Phase III, multicenter, randomized, open-label, assessor-blinded, parallel two-arm, controlled clinical trial that is sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (www.attract.wustl.edu; NCT00790335). Four companies (Bayer Healthcare, BSN Medical, Covidien, and Genentech) provide additional support but play no role in the study design, execution, or data analysis. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all analyses, and the drafting and editing of this article.

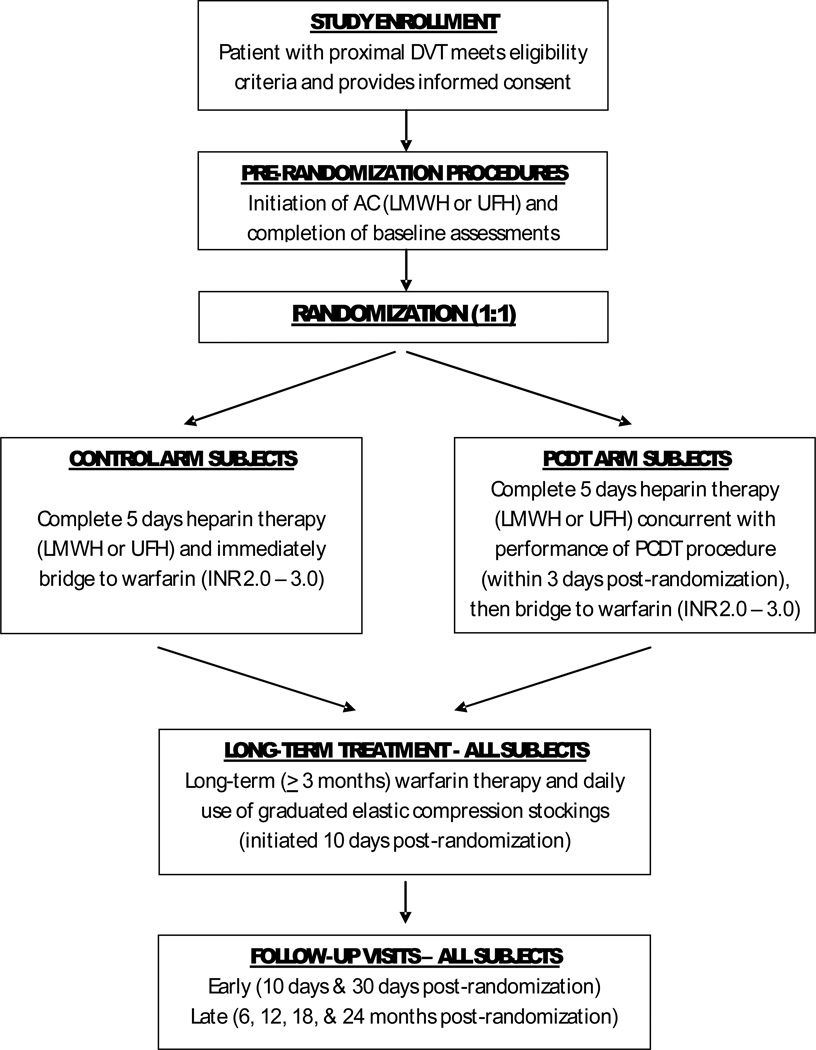

Subjects are enrolled in 40–60 U.S. Clinical Centers, and are followed for 24 months (Figure 1). The study’s conduct is approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Washington University in St. Louis and all participating Clinical Centers. The study is conducted under an investigational drug exemption (IND) granted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. To date (January 10, 2013), 392 patients have been enrolled. The study is led by a multidisciplinary Steering Committee (Appendix 1), and is monitored by an independent, NHLBI-appointed Data Safety Monitoring Board.

FIGURE 1. ATTRACT STUDY SCHEMA.

Patient Population

The study includes patients with symptomatic proximal DVT that involves the iliac, common femoral, and/or femoral vein (with or without other involved veins), since these patients are at high risk for PTS (1,11). Patients who are outside the 16–75 years age range, who are pregnant, or who have active cancer, recent major surgery or obstetrical delivery, an intracranial lesion, or established PTS are excluded (see Appendix 2 for full criteria).

Randomization and Stratification

Patients who meet the eligibility criteria and provide informed consent are randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either PCDT + standard DVT therapy or standard DVT therapy alone. Central automated randomization is performed using a web-based system at the study’s Data Coordinating Center (DCC) (Ontario Clinical Oncology Group, Hamilton, Ontario) that leads the investigator or coordinator through questions related to patient eligibility and stratification category, and then provides treatment group allocation, thereby ensuring concealment. Randomization is stratified on two factors: a) anatomic extent of the DVT (whether or not the common femoral vein and/or iliac vein is involved, since studies have observed PTS to be more frequent and more severe for iliofemoral DVT (1,10)); and b) Clinical Center. The complete randomization sequence, blocked in randomly varying block sizes, was computer-generated by a DCC statistician who is otherwise uninvolved with the study.

Standard DVT Therapy

Subjects in both treatment arms receive initial weight-based anticoagulant therapy with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH) (per local hospital nomogram) for at least 5 days and until the INR ≥ 2.0 on two consecutive draws on different days (4). Warfarin is started the day of randomization in Control arm subjects, or after PCDT is completed in PCDT arm subjects. The recommended intensity (target INR 2.0 to 3.0) and duration (3 months or longer, per international guidelines) of therapy are the same for subjects in the two arms (4). Before start-up, the credentials for co-investigators overseeing medical therapy, and each site’s anticoagulation monitoring procedures, are reviewed and approved by a Medical Therapy Credentialing Committee.

Subjects in both treatment arms are provided sized-to-fit, knee-high, 30–40 mmHg, graduated elastic compression stockings at the 10-day follow-up visit. We do not initiate compression therapy earlier because leg swelling can decrease markedly during the first 10 days which makes it difficult to fit the stockings. In addition, some patients’ legs are very tender initially, and published studies differ on whether very early compression influences the risk of developing PTS (14). A new pair of stockings is provided every 6 months. Initially, and at each visit, the importance of daily stocking use is reinforced.

PCDT Intervention

PCDT is performed by a board-certified endovascular physician whose credentials and experience are reviewed and approved by an Interventions Credentialing Committee, using a protocol that is based upon published practice guidelines (15). Venous access is established using ultrasound guidance, and a venogram is performed. The initial delivery of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) (Activase, Genentech, South San Francisco) may occur using one of three methods. If there is good inflow to the popliteal vein (i.e. the lower half of the popliteal vein and at least one major calf vein tributary are free of occlusive thrombus) one of the following techniques is used: (a) “Isolated Thrombolysis” using the Trellis Peripheral Infusion System (Covidien, Inc., Mansfield, MA) – two catheter-mounted balloons on the Trellis catheter are inflated to “isolate” a thrombus-bearing venous segment, rt-PA is delivered into the thrombus via sideholes in the catheter, and an oscillating wire within the catheter provides intrathrombus drug dispersion; or (b) “PowerPulse Thrombolysis” using the AngioJet Rheolytic Thrombectomy System (MEDRAD Interventional - Bayer, Minneapolis, MN) – rt-PA is delivered and rapidly dispersed within the thrombus via a powerful pulse-spray from the AngioJet catheter. A maximum of 25 mg of rt-PA may be delivered during the initial procedure. If there is poor inflow to the popliteal vein, a third technique (“Infusion-First Thrombolysis”) is used – this entails placement of a multisidehole catheter across the venous thrombus and rt-PA infusion at 0.01 mg/kg/hr, up to a maximum of 1 mg/hr, for up to 30 hours.

After initial rt-PA delivery, investigators may tailor subsequent adjunctive therapy to individual patient circumstances. The physician may use additional rt-PA boluses (≤ 5 mg), balloon maceration, aspiration thrombectomy, and/or mechanical thrombectomy to eliminate residual thrombus. Continued infusion of rt-PA via a multisidehole catheter (0.01 mg/kg/hr) may also be used after any of the above initial PCDT techniques but for the entire treatment, the maximum allowable rt-PA dose is 35 mg. Treatment is discontinued when: (a) ≥ 90% thrombus removal has been achieved with restoration of flow; (b) the 35 mg rt-PA maximum dose or 30 hour maximum infusion duration is reached; or (c) the patient suffers clinically overt bleeding or another complication that mandates cessation of therapy. Obstructive lesions in the iliac or common femoral vein may be treated with balloon angioplasty and/or stent placement; femoral vein obstructive lesions may be treated with balloon angioplasty.

Concomitant Anticoagulation

The INR is required to be no greater than 1.6 when PCDT is started. For the on-table parts of the initial PCDT session and any follow-up sessions, patients receive full therapeutic anticoagulation with twice-daily weight-based LMWH injections or intravenous UFH (target PTT corresponding to 0.3 – 0.7 IU/ml anti-Xa activity on the site’s heparin assay). During continuous rt-PA infusions, patients either receive twice-daily weight-based LMWH injections (full therapeutic dose), or intravenous UFH at 6–12 units/kg/hr (maximum allowed 1000 units/hr) to maintain a subtherapeutic PTT (less than twice control).

Peri-Procedure Use of Retrievable IVC Filters

IVC filter placement is discouraged in patients undergoing Infusion-First Thrombolysis. For patients treated with Isolated Thrombolysis or PowerPulse Thrombolysis, a retrievable filter may be used at physician discretion if there is thrombus in the IVC or iliac vein, and removed as soon as possible.

Outcome Assessments

Patients return for follow-up at 10 days, 30 days, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months post-randomization (Table I).

TABLE I.

Schedule of Outcome Assessments

| ASSESSMENT | Baseline | Initial Tx |

10 days |

30 days |

6 mo | 12 mo |

18 mo |

24 mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg Pain (Likert) | X | X | X | |||||

| Leg Circumference | X | X | X | |||||

| Venous QOL (VEINES) | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| General QOL (SF-36v2) | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Duplex Ultrasound | X | X | X* | |||||

| Venogram (PCDT Arm Only) | X** | |||||||

| Cost Diary Review | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Villalta Scale to Assess PTS | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| VCSS Scale | X | X | X | X | ||||

| CEAP Classification | X | X | X | X |

Performed in a subgroup of patients

Performed pre- and post-PCDT

Efficacy Outcomes

The study’s primary efficacy outcome is PTS, defined as a score of 5 or greater on the Villalta PTS Scale (Appendix 3) in the leg with the index DVT, or an ulcer in that leg, at any time from the 6-month post-randomization follow-up visit to the 24-month visit (inclusive).

PTS is a “syndrome” which produces a range of symptoms and clinical signs which differ in character and severity among patients. Since there is no gold standard objective test for PTS, validation of PTS measures has relied upon showing that they correlate with important health outcomes such as quality of life, and with known anatomic/physiologic findings of chronic venous disease (16). The Villalta PTS Scale combines patient self-assessment of 5 common symptoms of PTS (pain, cramps, heaviness, paresthesias, pruritus) with clinician assessment of 6 common clinical signs of PTS (pretibial edema, skin induration, hyperpigmentation, pain during calf compression, venous ectasia, redness), with each scored as 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe). The points are added to reach a total score.

We chose Villalta’s PTS Scale as the study’s primary measure to diagnose and grade PTS for the following reasons: a) It is reliable, valid, and responsive to change (17,18). The presence of PTS by a Villalta’s score > 5 is a better predictor of clinically important QOL impairment than imaging criteria (16); b) It evaluates both symptoms and clinical signs; c) It allows PTS severity to be assessed on a continuum (total score 0–33) and by category (present or absent; mild, moderate, severe); d) It has been used successfully in previous PTS research, including multicenter trials (1,11,17–20); e) Villalta scores correlate with anatomic/physiologic measures of chronic venous disease including abnormal venograms and venous pressures (21,22); and f) the Villalta PTS Scale is endorsed by the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis as the standard to assess the presence and severity of PTS (17).

A double-blinded design with sham PCDT procedures was considered but this approach was rejected since: a) catheter placement for a sham procedure would increase the risk of bleeding and recurrent VTE in Control Arm patients; b) it would be complex and unlikely to reliably achieve blinding; and c) it would cause patient hardship and interfere with quality of life and cost-effectiveness assessments. Because patients are not blinded, high priority has been attached to blinding and standardized training of the clinicians evaluating PTS signs. The day before follow-up visits, subjects receive a telephone reminder to not wear compression stockings on the visit day, and to not reveal to study staff whether they received PCDT. The Villalta assessment is performed on each leg, and assessors are blinded to which leg had the DVT. Site personnel are asked to schedule follow-up visits for as late as possible in the afternoon to allow PTS symptoms and signs to manifest.

The Villalta assessment is supplemented by the blinded administration of two additional measures, the Clinical-Etiologic-Anatomic-Pathophysiologic (CEAP) Classification System and the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS), at the 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-up visits (23,24). Also at these visits (and at baseline), health-related QOL is assessed with patient self-completion of the generic SF-36 QOL measure and the venous disease-specific VEINES-QOL measure (25).

To evaluate if PCDT speeds relief of acute DVT symptoms, patients are also assessed using a 7-category Likert scale to describe leg pain severity, the Villalta Scale, and standardized measurement of calf circumference at baseline and at the 10-day and 30-day follow-up visits.

Safety Outcomes

Investigators are required to report episodes of suspected clinically overt bleeding, recurrent VTE, or death. The primary safety outcome is the proportion of patients with major bleeding within 10 days post-randomization. Clinically overt bleeding is classified as “major” if it is associated with a hemoglobin drop of at least 2.0 g/dl, transfusion of ≥ 2 units of red blood cells, or involvement of a critical site (e.g., intracranial). Less severe clinically overt bleeding is classified as “minor”. Episodes of suspected symptomatic recurrent VTE are assessed and reported in a standardized way during follow-up.

Independent Adjudication

Data on suspected clinical outcome events are reviewed at the DCC by an Independent Central Adjudication Committee of thrombosis clinicians who are blinded to patients’ treatment allocation.

Imaging Outcomes

Quantitative assessment of pre-PCDT and post-PCDT venograms, using the components of the Marder score that describe the proximal veins, is done to estimate the amount of thrombus removed (26).

At 1-year follow-up, venous Duplex ultrasonography is performed in a consecutive subgroup of 142 patients in both treatment arms in seven participating Clinical Centers to assess for the presence of venous valvular reflux and to quantify residual deep vein thrombus. The goal of this substudy is to determine if prevention of valvular reflux and/or venous obstruction is a key mechanism underlying any effect of PCDT upon development of PTS. The exams are performed in standardized fashion by Clinical Center sonographers blinded to treatment allocation, and are analyzed by blinded examiners in an independent Ultrasound Core Laboratory (VasCore, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA).

Economic Outcomes

The goals of the health economic study are to compare 2-year DVT-related medical care costs between the two treatments groups and, if PCDT + standard therapy is found to be both more effective and more costly than standard therapy alone, to evaluate the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained from a U.S. societal perspective. Data relating to direct and indirect costs are collected from study intake through the 2-year follow-up period. Hospitalization costs are estimated using a combination of: (a) procedural resource use data and standard resource-based costing methods; and (b) hospital billing data, with charges converted to costs using department level cost-to-charge ratios. Indirect costs are estimated from data relating to lost time from work, decreased productivity, and informal caregivers’ time. Assessment of outpatient resource utilization and indirect costs is aided by use of a “cost diary”, in which subjects record outpatient medical encounters, travel time, and out of pocket expenses related to their DVT. For the cost-effectiveness analysis, preference-based utility scores will be calculated from the SF-36 data collected, using a validated U.S.-specific scoring algorithm (27).

Because the clinical impact and costs associated with PCDT may accrue beyond 2 years, a Markov model (28) will be used by the Economic Core Laboratory (Mid-America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO) to evaluate the long-term cost-effectiveness of PCDT. Data from ATTRACT and other studies, including a large prospective North American study on the natural history of DVT, will inform the model (3).

Sample Size Determination

Based on previous studies, we estimated that 30% of Control arm subjects will develop PTS between 6 and 24 months (1,19). Based on PTS reductions achieved in earlier studies (8–11,15), we hypothesized that PCDT would reduce the proportion of patients who develop PTS by at least 33%. Accepting a 5% chance of incorrectly concluding there is a difference in the proportion of subjects with PTS at 24 months (α error=0.05; two-sided), and the requirement that the study has an 80% chance (β error=0.2) of detecting a true difference if PCDT truly reduces PTS by 33%, and assuming a maximum 10% loss to follow-up, we plan to randomize 346 subjects to each group, for a total of 692 subjects.

Data Analysis

Two data sets will be considered: (a) a full analysis set that consists of all subjects randomized; and (b) a per-protocol set that includes everyone in the full analysis set, except for any subjects who: (1) randomized to PCDT but did not receive endovascular therapy, (2) randomized to Control but had skin puncture for PCDT or any thrombolytic therapy, or (3) received less than 4 weeks of anticoagulation. The primary analysis, using the full analysis set and analyzed per the intention-to-treat principle, is a comparison of the proportion of subjects in each arm who developed PTS, defined as a total Villalta score of ≥ 5 or the presence of ulcer in the limb with the index DVT at the 6-month follow-up visit, or subsequently during the 24 months after randomization (stratum-adjusted Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test). Testing will be two-sided. A p-value of 0.05 or less will be considered statistically significant.

Secondary analyses will be performed using both analysis sets. To account for multiple testing, a two-sided p-value of ≤ 0.01 will be considered statistically significant. The stratum-adjusted Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test will be used to compare the proportions of subjects in each group with (a) major or any (major + minor) bleeding during the 10 days after randomization, and between 11 days and 24 months; (b) symptomatic VTE within 24 months; and (c) death within 1 month or within 24 months.

Changes in QOL scores between baseline and 24 months will be compared between the two treatment groups using a linear regression model to adjust for the strata. PTS severity classification (none, mild, moderate, severe) at 24 months will be compared between the two arms (4 × 2 table) using an exact Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with severity as a single ordered factor. The mean absolute change in leg pain severity (Likert scores) from baseline to 10 days and to 1 month post-randomization will be compared using analysis of co-variance. Measured and percentage change in leg circumference from baseline to 10 and 30 days will be compared using linear regression modeling.

The extent of residual thrombosis and venous reflux will be compared between the two groups using the obstruction and reflux scores of the Venous Segmental Disease Scale (29). These scores, and the post-PCDT Marder scores, will be correlated with the presence and severity of PTS at 24 months.

Discussion

Clinical practice guidelines of the Society of Interventional Radiology (2006) and the American Heart Association (2011) suggest consideration of adjunctive CDT or PCDT for selected patients with extensive proximal DVT, whereas the 2012 American College of Chest Physicians’ guidelines suggest anticoagulant therapy alone over CDT (4,17,30). However, these suggestions are not based on data from rigorously performed RCTs. A recent multicenter RCT (CaVenT) found a 26% relative reduction (41% versus 56%, p = 0.047) in PTS at 2 years in proximal DVT patients who received CDT (11). The investigators reported 3% major bleeds and 6% “clinically-relevant” bleeding events in CDT-treated patients, with no bleeding events in the Control arm. While CaVenT was well-performed, its influence on practice may be limited because: (a) the study reported outcomes data on just 189 patients, making its findings imprecise; (b) the study evaluated CDT rather than PCDT, which may be more effective (from the added mechanical component of thrombus removal) and associated with less bleeding (due to reduced rt-PA dose and exposure duration) than CDT; and (c) in CaVenT, CDT was performed in just 4 treatment centers in Southern Norway. With more than 50 treatment centers across the United States, the results of ATTRACT will be more generalizable to a broader range of DVT patients and PCDT operators.

We selected the proportion of patients with PTS over 2 years as our primary outcome because most patients who ultimately develop PTS manifest the condition within 2 years (1,7,11). To minimize the potential for bias from differential application of co-interventions, there is standardization of anticoagulant therapy and compression therapy in both groups. To minimize bias from the open-label design, clinical outcome evaluators and event adjudicators are blinded to treatment allocation, and a number of objective secondary outcome assessments (VCSS, CEAP, venograms, ultrasounds) are being performed.

After reviewing the literature and surveying our investigators, we concluded that: (a) no single PCDT method was clearly superior to others; (b) drug-only CDT with long rt-PA infusions was likely to be less efficient and less safe than PCDT; (c) most endovascular physicians preferred “faster” PCDT methods that use lower doses of rt-PA and facilitate outpatient or short-stay inpatient DVT treatment; and (d) physicians were most likely to achieve representative clinical results if permitted to use PCDT methods with which they were familiar. We therefore allow the use of multiple PCDT methods and encourage the use of fast PCDT when good venous inflow favors completion of clot removal in a single procedure.

In conclusion, ATTRACT will be the first U.S. multicenter RCT to determine the long-term clinical impact of endovascular thrombolysis in proximal DVT. This study will greatly aid patients, physicians, payors, and policy-makers who face decisions on the use of catheter-based DVT therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The ATTRACT Study is supported by awards U01-HL088476 and U01-HL088118 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (National Institutes of Health). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the NHLBI or NIH. Additional support for the study was provided by Bayer Healthcare, BSN Medical, Covidien, and Genentech. The authors wish to recognize the Society of Interventional Radiology Foundation, including Drs. Stephen Kee and John Rundback, for its support for the planning and conduct of the ATTRACT Study.

Dr. Susan Kahn is the recipient of a National Investigator (chercheur national) Award of the Fonds de la recherché en santé du Quebec (FRSQ).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kahn SR, Shrier I, Julian JA, et al. Determinants and time course of the postthrombotic syndrome after acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:698–707. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-10-200811180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn SR, Shbaklo H, Lamping DL, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life during the 2 years following deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1105–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guanella R, Ducruet T, Johri M, et al. Economic burden and cost determinants of deep vein thrombosis during 2 years following diagnosis: a prospective evaluation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(12):2397–2405. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2):e419S–e494S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meissner MH, Manzo RA, Bergelin RO, et al. Deep venous insufficiency: the relationship between lysis and subsequent reflux. J Vasc Surg. 1993;18:596–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hull RD, Marder VJ, Mah AF, et al. Quantitative assessment of thrombus burden predicts the outcome of treatment for venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2005;118(5):456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prandoni P, Frulla M, Sartor D, et al. Venous abnormalities and the post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:401–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnesen H, Hoiseth A, Ly B. Streptokinase or heparin in the treatment of deep vein thrombosis. Acta Med Scand. 1982;211:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turpie AGG, Levine MN, Hirsh J, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) vs heparin in deep vein thrombosis: results of a randomized trial. Chest Suppl. 1990;97(4):172S–175S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plate G, Akesson H, Einarsson E, et al. Long-term results of venous thrombectomy combined with a temporary arterio-venous fistula. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4:483–489. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80788-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enden T, Haig Y, Klow N, et al. Long-term outcomes after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vedantham S, Grassi CJ, Ferral H, et al. Reporting standards for endovascular treatment of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:417–434. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000197359.26571.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. 2008 Sep 15; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roumen-Klappe den Heijer M, van Rossum J, et al. Multilayer compression bandaging in the acute phase of deep-vein thrombosis has no effect on the development of the post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;27(4):400–405. doi: 10.1007/s11239-008-0229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vedantham S, Thorpe PE, Cardella JF. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis with use of endovascular thrombus removal. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:435–447. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000197348.57762.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahn SR, Desmarais S, Ducruet T, et al. Comparison of performance of two clinical scales to diagnose the post-thrombotic syndrome: correlation with patient-reported disease burden and valvular reflux. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(4):907–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahn SR, Partsch H, Vedantham S, Kearon C, et al. Definition of post-thrombotic syndrome in the leg for use in clinical investigations: a recommendation for standardization. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:879–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahn SR. Measurement properties of the Villalta scale to define and classify the severity of the post-thrombotic syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(5):884–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Prins MH. Below-knee elastic compression stockings to prevent the post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:249–256. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-4-200408170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahn SR, Kearon C, Julian JA, et al. Predictors of the post-thrombotic syndrome during long-term treatment of proximal deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:718–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villalta S, Prandoni P, Cogo A, et al. The utility of non- invasive tests for detection of previous proximal-vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:592–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolbach DN, Neumann HAM, Prins MH. Definition of the post-thrombotic syndrome, differences between existing classifications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eklof B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, et al. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meissner MH, Natiello C, Nicholls SC. Performance characteristics of the venous clinical severity score. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:889–895. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.128637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahn SR, Ducruet T, Lamping DL, et al. The VEINES-QOL/Sym questionnaire is a valid and reliable measure of quality of life and symptoms in patients with deep vein thrombosis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(10):1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marder VJ, Soulen RL, Atichartakarn V. Quantitative venographic assessment of deep vein thrombosis in the evaluation of streptokinase and heparin therapy. J Lab Clin Med. 1977;89(5):1018–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):271–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck JR, Pauke SG. The Markov process in medical prognosis. Med Decis Making. 1983;3(4):419–458. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8300300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ricci MA, Emmerich J, Callas PW, et al. Evaluating chronic venous disease with a new venous severity scoring system. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:909–915. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(16):1788–1830. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.