Abstract

Background:

Health is defined as the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being than just the absence of disease or infirmity. In order to measure health in the community, a reliable and validated instrument is required.

Objectives:

To adapt and translate the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) for use in India, to study its validity and reliability and to explore its higher order factor structure.

Materials and Methods:

Face-to-face interviews were conducted in 184 adult subjects by two trained interviewers. Statistical analyses for establishing item-level validity, scale-level validity and reliability and tests of known group comparison were performed. The higher order factor structure was investigated using principal component analysis with varimax rotation.

Results:

The questionnaire was well understood by the respondents. Item-level validity was established using tests of item internal consistency, equality of item-scale correlations and item-discriminant validity. Tests of scale-level validity and reliability performed well as all the scales met the required internal consistency criteria. Tests of known group comparison discriminated well across groups differing in socio-demographic and clinical variables. The higher order factor structure was found to comprise of two factors, with factor loadings being similar to those observed in other Asian countries.

Conclusion:

The item-and scale-level statistical analyses supported the validity and reliability of SF-36 for use in India.

Keywords: Health surveys, reliability, questionnaires, quality of life, translations, validity

Introduction

Health is defined as the state of complete physical, mental and social well-being than just the absence of disease or infirmity.(1) Therefore, patient's perspective about his/her state of health is recognized as an important parameter for assessing health outcomes and efficacy of an intervention. Validated and reliable self-reported questionnaires(2,3) are needed to enable this assessment.

The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)(4) is a widely used generic health-related quality of life (QoL) instrument consisting of 36 questions and measuring health in eight dimensions: physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical health problems (RP), bodily pain (BP), social functioning (SF), general mental health covering psychological distress and well-being (MH), role limitations due to emotional problems (RE), vitality, energy and fatigue (VT) and general health perceptions (GH). SF-36 has been adapted and translated into several languages,(5,6) and its validity and reliability established in several countries.(7)

SF-36 has been used in India to assess health outcomes in several diseased populations.(8–15) However, no studies regarding the validity and reliability of SF-36 in the general Indian population have been cited in electronic scientific databases. The primary objectives of this study were to adapt and translate SF-36 for use in India and to study its validity and reliability. Additionally, the study aimed to explore the higher order factor structure of the eight SF-36 scales.

Materials and Methods

Adaptation and translation

Conceptually equivalent cultural adaptations(5) were made to the questionnaire to make it suitable in the Indian context. In PF01, vigorous activities such as lifting heavy objects was exemplified as lifting a bucket of water to improve the understandability of the question. In PF02, moderate activities such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling or playing golf were replaced by brooming, shopping for groceries and cooking, as these activities can be considered to be equivalently moderate.

Climbing several flights of stairs was explained as climbing five to six floors (PF04), and one flight of stairs was expressed as one floor (PF05). One mile was expressed as 1 km (PF07) in accordance with the metric standards in India. A block was represented by a distance of 100 m (PF08 and PF09). Words like pep, dumps and blue in VT01, MH02 and MH04, respectively, were translated appropriately to capture their essence.

The questionnaire items were translated from English into Hindi by a professional experienced in translating health survey questionnaires. The translated version was back-translated into English by an independent person followed by a review to control for possible discrepancies. The final translated version evolved following an iterative process,(6) which included pilot-testing and incorporating appropriate changes.

Data collection

The study sample was selected from Mumbai, its suburbs and a village in its vicinity following purposive sampling. Face-to-face interviews were conducted by two trained interviewers in residential areas, industrial estates, business centers, offices and market place by selecting the units systematically and interviewing the people present at the time of visit.

The Institutional Review Board of one of the co-authors’ institute in India approved the study. Subjects 18 years and above who could communicate in Hindi were included. The study purpose was explained to the subjects and interviews were performed after obtaining written informed consent. Two people did not participate in the study, one because of lack of time and the other due to being psychologically disturbed due to the death of a family member.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 15.(16)

Tests of item internal consistency, equality of item-scale correlations and item-discriminant validity(17) were carried out to establish item-level validity. Item internal consistency is considered satisfactory if an item correlates 0.40 or more with its hypothesized scale after correction for item-scale overlap. Equality of item-scale correlations is considered satisfied when items have similar item-scale correlations. Item-discriminant validity is supported if the correlation between an item and its hypothesized scale is significantly higher than the correlations between that item and the other scales.

Scale-level validity and reliability were assessed by testing whether the SF-36 scale scores showed substantial variability and if their reliability estimated using the internal consistency method (Cronbach alpha coefficient) was acceptable, namely 0.70 or higher for group comparisons,(18) and whether the internal consistency of each scale was higher than the correlation between that scale and the other scales, which tests if each scale measured a distinct health concept.(17)

Tests of known group comparison were performed to assess the ability of SF-36 to distinguish between groups differing in factors known to affect QoL. Gender, age, residential area and comorbidities were used as grouping variables. Non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA) were performed to test the statistical significance of observed differences between the groups.

Exploratory factor analyses were performed on the eight SF-36 scales using principal component analysis with varimax rotation(19) to examine the existence of higher order factor structure in the Indian general population.

Results

Sample characteristics

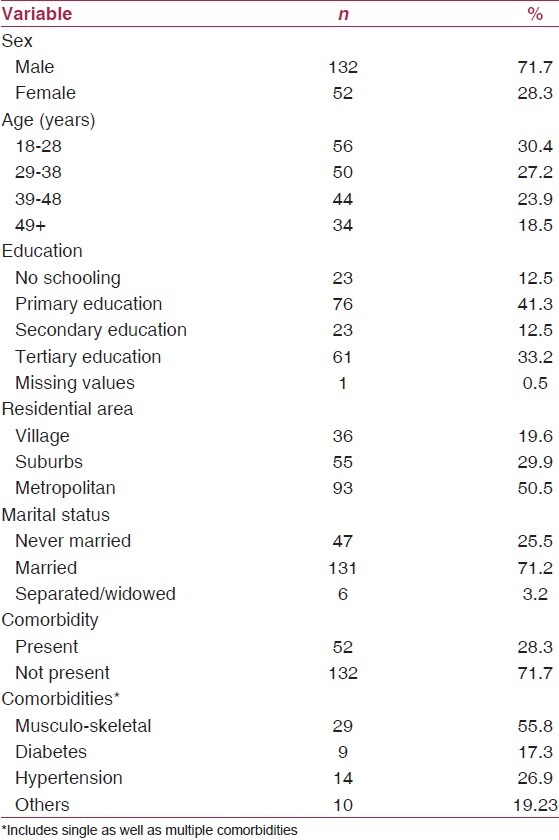

Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic and clinical attributes of the study population. The population ranged in age from 18 to 76 years, with a mean age of 37.44 years.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

Statistical analyses

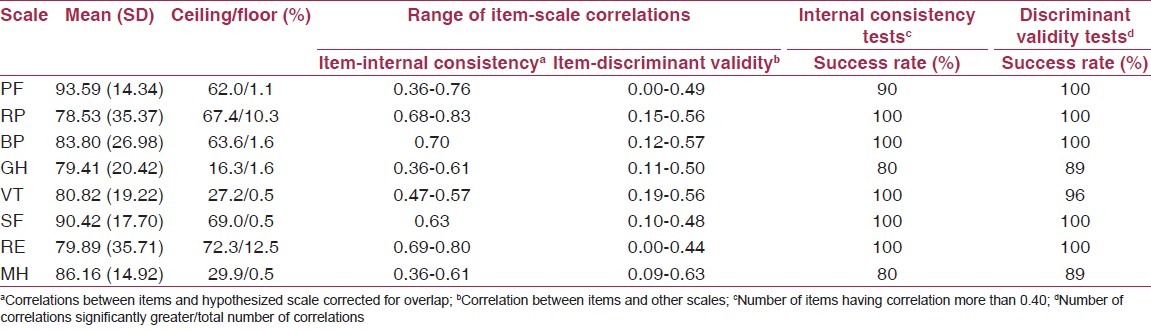

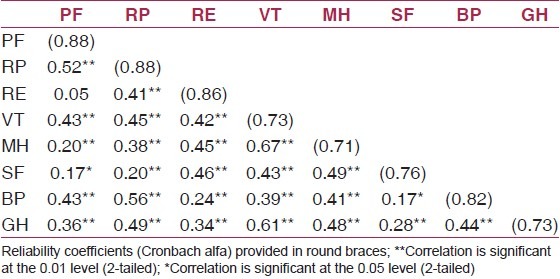

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the eight SF-36 scales. Within each scale, the correlation between items and their hypothesized scale were of similar magnitude. Item internal consistency and item-discriminant validity criteria were met for most of the scales. The floor effect was found to be less than 10% for all the scales except RP and RE. A ceiling effect of more than 50% was observed for all the scales except GH, VT and MH. For all the scales, the internal consistency (Cronbach alfa) equaled or exceeded 0.70 [Table 3]. The internal consistency of each scale exceeded the correlations between that scale and the other scales.

Table 2.

SF-36 scale descriptives, tests of item internal consistency and discriminant validity

Table 3.

Interscale correlations and reliability coefficients for the eight SF-36 scales

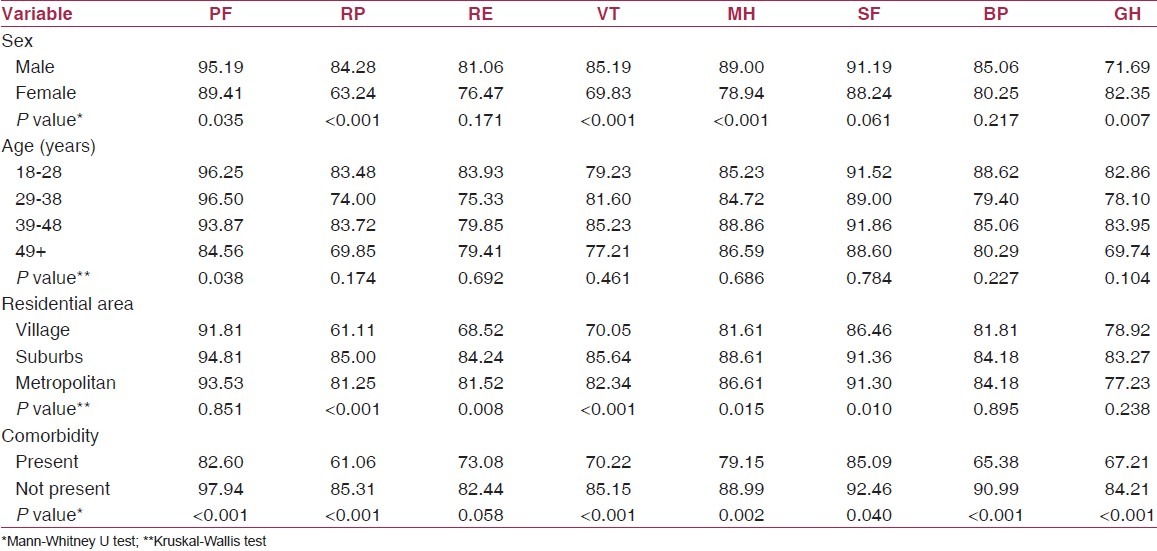

Table 4 summarizes the tests for known group comparisons. Females scored lower on all the eight scales, with the differences being statistically significant in PF, RP, VT, MH and GH. With age, the range of scores related to physical health scales (PF, RP, BP and GH) were more than those related to mental health scales (RE, VT, MH and SF). Scales associated with mental health showed significantly different scores in groups classified as per residential area, and only one physical health scale (RP) was found to be significantly different. All the scales were found to be lower in the sub-group having comorbidities, and these differences were significant for all the scales except for RE.

Table 4.

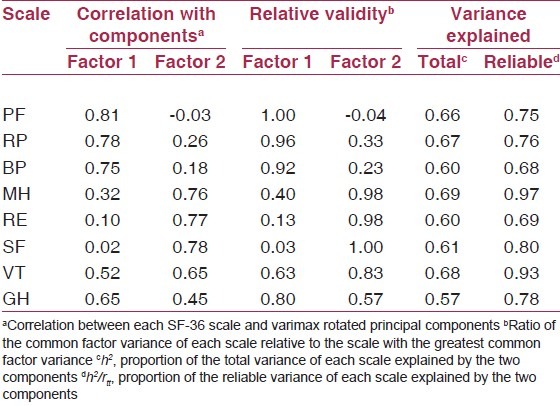

Summary of principal component analysis for the eight SF-36 scales

Exploratory factor analysis of the eight SF-36 scales yielded a two-factor solution [Table 5]. PF, RP and BP correlated more with factor 1, whereas SF, RE and MH correlated more with factor 2. VT and GH scales correlated moderately with both the factors. The two principal components explained 63.42% of the total variance, which was within the prescribed range.(20,21) The obtained two-factor structure was similar to that obtained in other studies (factor 1 as “physical” and factor 2 as “mental” domains of health underlying the SF-36).(22)

Table 5.

Mean SF-36 scale scores in relation to socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

Discussion

The study sample can be considered adequate because a sample of 100 or more has been recommended for reliability and validity(23,24) studies, and to perform second-order analysis on SF-36 scales.(6,25) SF-36 translation and validation studies in several languages(26–29) have been carried out using similar sample sizes. The overrepresentation of males (72%) in the study population is not an issue as the study did not aim at generating normative QoL data.

SF-36 was adapted to make it suitable for use in India. Similar adaptations have also been done while translating SF-36 for use in other countries in order to preserve the conceptual meaning of the original question to make it relevant within each country and language. In Iran,(30) in items regarding activities, bowling and playing golf were changed to light sport activities, mile was changed to kilometer and walking one block or walking several blocks were changed to walking one alley or several alleys to refer to a similar distance. In the United Kingdom,(31) walking one block was changed to walking 100 yards and downhearted and blue was changed to downhearted and low. In Sweden,(31) walking in the forest or gardening was used as an example for moderately strenuous activity instead of bowling or playing golf.

The adapted and translated version was well understood by the respondents as there was a low (1%) missing data at both item and scale levels, and all the response choices were used. The suggested Cronbach alfa values of 0.70 for group-level comparison(7) were met for all the scales, thus, supporting the item homogeneity and internal consistency across scales. Tests of known group comparison discriminated well among the groups, differing in socio-demographic and clinical variables. These findings were similar to those reported in other studies.(30,32–35) In Greece,(32) women reported worse health than men. Moreover, age was an important health status factor affecting physical health relatively more than mental health. Also, in Iran,(30) SF-36 discriminated well between sub-groups of people differing in gender and age. The findings demonstrated that women and old people had poorer health as compared with men and younger people.

Exploratory factor analyses were performed as the higher order factor structure of SF-36 has not been established in the general Indian population.(25) The higher order factor structure was found to be similar to that in other countries.(22) The two factors explained 63.42% of the total variance of the SF-36 scale scores and 68-97% of the reliable variance of each scale. SF and MH showed, respectively, lower and higher association with physical domain in congruence with the findings from other Asian countries.(26,27,30,36)

To conclude, the item and scale level analyses supported the validity and reliability of the translated and adapted version of SF-36 for use in India. Studies with larger sample size with representative general Indian population are encouraged to generate normative QoL data.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Handbook of basic documents. 46th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saw SM, Ng TP. The design and assessment of questionnaires in clinical research. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hays RD, Anderson R, Revicki D. Psychometric considerations in evaluating health-related quality of life measures. Qual Life Res. 1993;2:441–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00422218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDowell I. Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2006. General health status and quality of life; pp. 520–703. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner AK, Gandek B, Aaronson NK, Acquadro C, Alonso J, Apolone G, et al. Cross-cultural comparisons of the content of SF-36 translations across 10 countries: Results from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:925–32. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, Leplège A, Sullivan M, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA project approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:913–23. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandek B, Ware JE, Jr, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Apolone G, Bjorner J, et al. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the SF-36 in eleven countries: Results from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1149–58. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muniyandi M, Rajeswari R, Balasubramanian R, Nirupa C, Gopi PG, Jaggarajamma K, et al. Evaluation of post-treatment health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among tuberculosis patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:887–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajeswari R, Muniyandi M, Balasubramanian R, Narayanan PR. Perceptions of tuberculosis patients about their physical, mental and social well-being: A field report from south India. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1845–53. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wig N, Lekshmi R, Pal H, Ahuja V, Mittal CM, Agarwal SK. The impact of HIV/AIDS on the quality of life: A cross sectional study in north India. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohli RM, Sane S, Kumar K, Paranjape RS, Mehendale SM. Assessment of quality of life among HIV-infected persons in Pune, India. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1641–7. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohli RM, Sane S, Kumar K, Paranjape RS, Mehendale SM. Modification of medical outcome study (MOS) instrument for quality of life assessment and its validation in HIV infected individuals in India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedi GS, Gupta N, Handa R, Pal H, Pandey RM. Quality of life in Indian patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1953–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haroon N, Aggarwal A, Lawrence A, Agarwal V, Misra R. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on quality of life. Mod Rheumatol. 2007;17:290–5. doi: 10.1007/s10165-007-0604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray J, Das SK, Gangopadhya PK, Roy T. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease-Indian scenario. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SPSS for Windows, Rel. 15.0.1. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B. Methods for testing data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability: The IQOLA project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:945–52. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IR. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware Je, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user's manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B, Kosinski M, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Brazier J, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: Results from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1167–70. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norman GR, Streiner DL. PDQ Statistics. 3rd ed. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker Inc; 2003. Exploratory factor analysis; pp. 144–55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bech P, et al. The factor structure of the SF-36 health survey in 10 countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1159–65. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Principles of biostatistics. 2nd ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peat J, Mellis C, Williams K, Xuan W. Health science research: A handbook of quantitative methods. 1st ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vet HC, Adèr HJ, Terwee CB, Pouwer F. Are factor analytical techniques used appropriately in the validation of health status questionnaires? A systematic review on the quality of factor analysis of the SF-36. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1203–18. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-5742-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam CL, Gandek B, Ren XS, Chan MS. Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 health survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1037–44. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leplège A, Ecosse E, Verdier A, Perneger TV. The French SF-36 health survey: Translation, cultural adaptation and preliminary psychometric evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1013–23. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren XS, Amick B, 3rd, Zhou L, Gandek B. Translation and psychometric evaluation of a Chinese version of SF-36 health survey in the United States. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The short form health survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:875–82. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller SD, Ware JE, Jr, Bentler PM, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Apolone G, et al. Use of structural equation modeling to test the construct validity of the SF-36 health survey in ten countries: Results from the iqola project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1179–88. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pappa E, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Validating and norming of the Greek SF-36 health survey. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1433–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6014-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Performance of the swedish SF-36 version 2.0. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:251–6. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015290.76254.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apolone G, Mosconi P. The italian SF-36 health survey: Translation, validation and norming. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1025–36. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabbah I, Drouby N, Sabbah S, Retel-Rude N, Mercier M. Quality of life in rural and urban populations in lebanon using SF-36 health survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:30. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam CL, Tse EY, Gandek B, Fong DY. The SF-36 summary scales were valid, reliable, and equivalent in a Chinese population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:815–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]