Abstract

Background:

Attracting doctors to rural posts is an ongoing challenge for health departments across different states in India. One strategy adopted by several states to make rural service attractive for medical graduates is to reserve post-graduate (PG) seats in medical colleges for doctors serving in the public sector.

Objective:

This study examines the PG reservation scheme in Andhra Pradesh to understand its role in improving rural recruitment of doctors and specialists, the challenges faced by the scheme and how it can be strengthened.

Materials and Methods:

Qualitative case study methodology was adopted in which a variety of stakeholders such as government officials, health systems managers and serving Medical Officers were interviewed. This was supplemented with quantitative data on the scheme obtained from the Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department in Andhra Pradesh.

Results:

The PG reservation scheme appears to have been one of the factors responsible in attracting doctors to the public sector and to rural posts, with a reduction in vacancies at both the Primary Health Centre and Community Health Centre levels. Expectedly, in-service candidates have a better chance of getting a PG seat than general candidates. However, problems such as the mismatch of the demand and supply of certain types of specialist doctors, poor academic performance of in-service candidates as well as quality of services and enforcement of the post-PG bond need to be resolved.

Conclusion:

The PG reservation scheme is a powerful incentive to attract doctors to rural areas. However, better monitoring of service quality, strategically aligning PG training through the scheme with the demand for specialists as well as stricter enforcement of the financial bond are required to improve the scheme's effectiveness.

Keywords: Andhra Pradesh, bond, medical education, post-graduate, rural service

Introduction

Recruiting and retaining qualified doctors in rural areas is a major challenge in India. For every 10,000 people, there are around 10 qualified physicians in urban areas but only one in rural areas. Not surprisingly, unqualified providers have largely occupied the rural workforce space. National surveys indicate that up to 63% of rural physicians have inadequate medical training.(1)

To attract doctors to government service and rural posts, at least 11 states in India have reserved post-graduate (PG) seats in medical colleges for doctors serving in the public sector. This takes advantage of the strong desire among medical graduates to become specialists and the considerably few PG seats available compared with the number of medical graduates. This study examines the PG reservation scheme in Andhra Pradesh. It has the following objectives: first, to examine the scheme's role in attracting doctors and specialists to rural posts; second, to describe some of the challenges the scheme faces; and third, to suggest ways in which the scheme can be further strengthened.

The Post-Graduate Reservation Scheme in Andhra Pradesh and its Evolution

The PG reservation scheme has been in existence for a long time in Andhra Pradesh. Many senior Medical Officers in the state Health Department had taken advantage of the scheme to get their PG degree.

To be eligible for this scheme, a doctor serving in the public sector currently has to complete continuous regular service of at least 2 years in a tribal area, 3 years in a rural area or 5 years of continuous regular service with the government.

Eligible Medical Officers take the PG entrance examination, but only compete among themselves for the reserved seats. Those who are selected are given extraordinary leave and sent on deputation. Hence, they continue to receive their full salary with all benefits, including grade increments and leave (GO Ms No. 260 dated 16th March 1975).

Fifty percent of the PG seats in pre- and para-clinical specialties (Anatomy, Physiology, Biochemistry, Pathology, Pharmacology, Microbiology and Forensic Medicine) and 30% of the seats in clinical specialties (such as Internal Medicine, Surgery, Gynecology, Pediatrics, ENT and Ophthalmology) in government medical colleges in the state are reserved for in-service candidates.

In private medical colleges, reservation for in-service candidates applies to the approximately 50% of PG seats that are filled through the PG entrance examination; the in-service quota does not apply to the other half of seats that are filled by the management of these private colleges. In-service candidates pay the regular fees for private colleges as prescribed by the state government.

Students using the quota have to sign a bond of Rs. 20 lakhs and are required to serve the state government for 5 years after completing their PG education. If they leave government service within the bond period, they are obliged to pay the bond amount and refund the salary received after starting their PG course.

Materials and Methods

The study uses a qualitative case study design. A variety of stakeholders were interviewed – Government Officials, PG students from both in-service and the general quota as well as MBBS students [Appendix 1]. Stakeholders were selected using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling and interviews were conducted using semi-structured questionnaires. Quantitative data was obtained from the Dr. NTR University of Health Sciences in Vijayawada, Directorate of Medical Education as well as the Directorate of Health Services.

The nature of the data available does not permit us to make a definitive causal statement about the impact of the scheme on vacancies and hence the scheme's role in attracting doctors to rural posts is described using associations between the number of candidates appearing for the scheme and vacancy positions in the public sector.

Medical Education in Andhra Pradesh

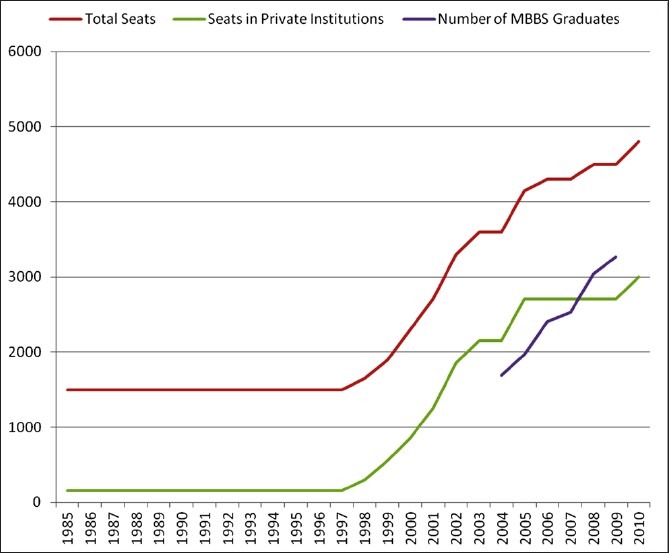

Andhra Pradesh, with approximately 76 million people, is India's fifth largest state. The state has 36 medical colleges offering both MBBS and PG medical education. There has been a huge increase in the number of medical colleges over the last decade, fuelling a surge in the number of MBBS graduates in the state [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Total number of MBBS seats and graduates in Andhra Pradesh. Source: Dr. NTR University for Health Sciences, Vijayawada, and Medical Council of India, New Delhi

Of the 4800 MBBS seats currently available, 2900 have been added after the year 2000, mostly in the private sector [Figure 1].(2) This is important because students at private institutions typically take large loans to pay for their education and will be inclined to look to recover their investment.

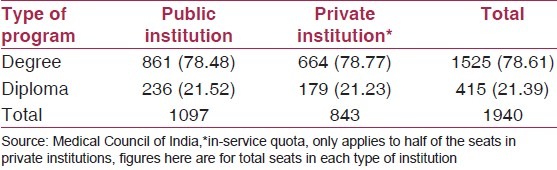

Most medical graduates aim to become specialists by completing PG training. However, the competition for PG seats is intense in Andhra Pradesh – there are less than 2000 PG seats for the 4800 MBBS students that graduate each year. This figure underrepresents the true extent of the competition, as a large number of these seats are in specialties that are not much sought after. The private sector accounts for over 60% of MBBS graduates in the state, but contains less than 45% of the PG seats in the state [Table 1].(3) PG courses in private colleges also tend to be extremely expensive compared to those in Government institutions.

Table 1.

Number of post-graduate seats in Andhra Pradesh

Findings

Easier admission to post-graduate programs for inservice candidates

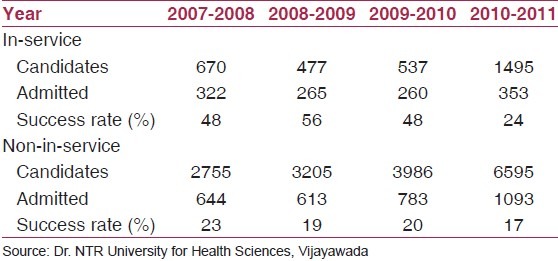

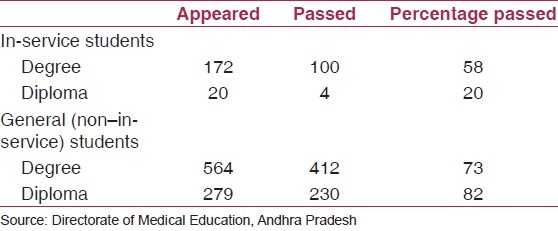

Most interviewees felt that using the in-service quota makes it easier for students to get a PG seat. “Entrance is easy for in-service” (candidates) is a quote from a PG student that reflects student perceptions of the scheme. This perception is backed by quantitative data [Table 2]. However, in 2010–2011, the success rate of those using the quota has reduced considerably. This can be attributed to the massive increase in the number of in-service candidates using this quota.(4)

Table 2.

Performance of candidates in the Andhra Pradesh PG entrance examination

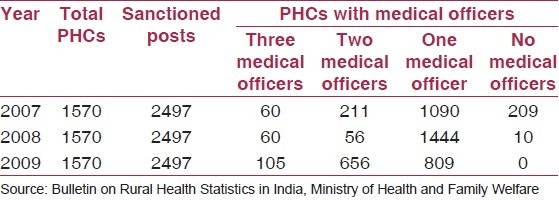

Reduced vacancies of medical officers at PHCs and specialists at CHCs

Over the past few years, there has been a significant improvement in the number of vacancies [Table 3] as well as, importantly, in the distribution of medical officers in the state. In 2009, no Primary Health Centre (PHC) was without a medical officer. Almost 40% of the PHCs in the state have two Medical Officers present, and only 2% of sanctioned posts are vacant (according to the latest available information).(5)

Table 3.

Medical Officer vacancies at primary health centers (PHC) in Andhra Pradesh(6)

Policymakers in the state emphasize the role of the scheme as an important factor in the reduction of vacancies. As one senior health department official put it, “just because of (this incentive) we have managed to hold 90% of the people who work in rural areas.” Another senior public health specialist in the state concurs and states that “it (the PG reservation scheme) did make a difference, the incentive makes a difference, the service quota has really increased willingness to work.”

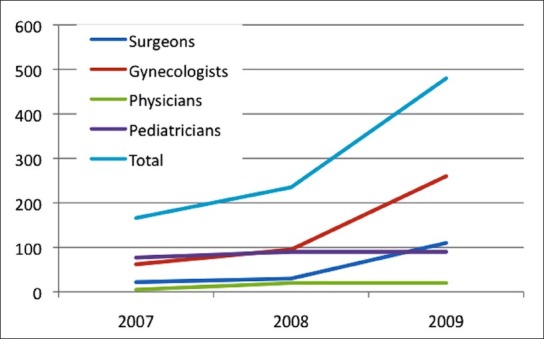

There has also been a progressive increase in the number of specialists at the Community Health Centre (CHC) level. In 2009, 72% of the sanctioned posts for specialists were filled [Table 4]. The vacancy situation varies across specialties; while there has been greater success in filling vacancies of gynecologists, the vacancy position is particularly acute for medicine specialists (physicians) and pediatricians [Figure 2].(5) More information is needed on the distribution of specialists by location and the percentage of these specialists who are in-service candidates to make a direct link between the scheme and filling of specialist vacancies at CHCs.

Table 4.

Position of specialists at CHCs in Andhra Pradesh(6)

Figure 2.

Number of specialists in Andhra Pradesh working at community health centers. Source: Bulletin on Rural Health Statistics in India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

However, government officials were confident that the problem of filling positions of specialists in district and sub-district hospitals could be overcome. A recent government order compels all PG graduates (who are not in-service candidates) to serve in the public sector for at least 1 year after the completion of their specialist education. This measure can potentially increase the number of specialists in government service, although experience in other states suggests that such requirements are difficult to enforce.

Mismatch of training opportunities with specialist needs

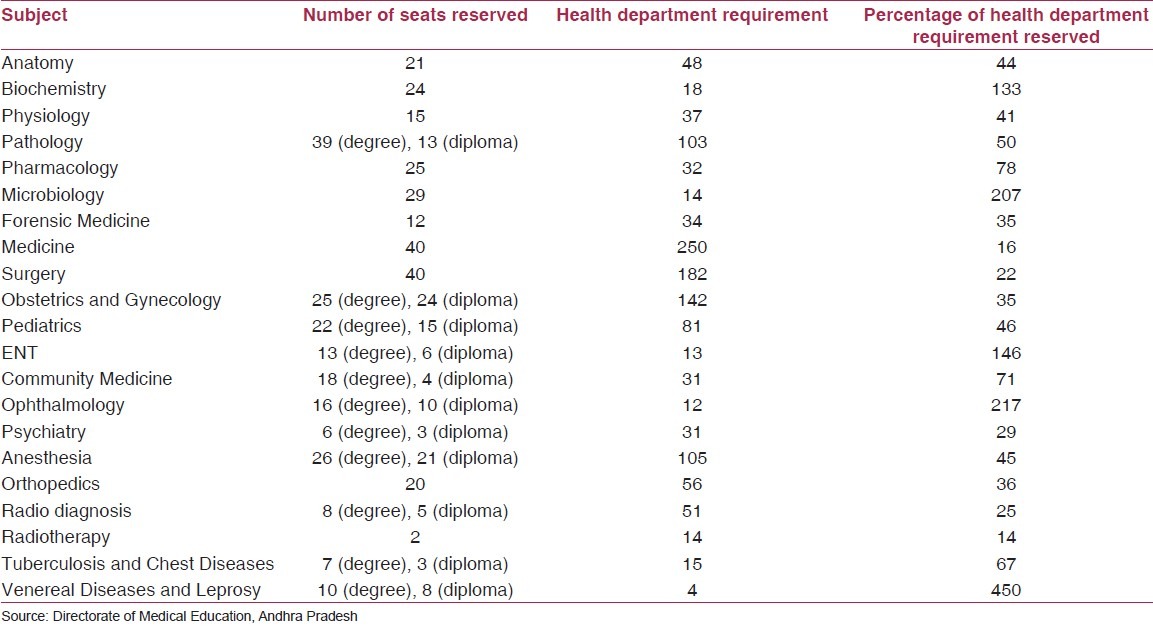

There is a mismatch between the opportunities available through the PG in-service quota and the need for specialists in government hospitals. In some subjects like biochemistry, microbiology and ENT and ophthalmology, considerably more seats than those required by the health department are reserved for in-service candidates. But, in subjects like surgery, medicine, pediatrics and gynecology, there are considerably few seats reserved in relation to requirements [Table 5].(8)

Table 5.

Reserved post-graduate seats for in-service candidates and requirement

Reducing this mismatch is vital as graduates using the in-service quota are compelled to work in government service for a period of 5 years after their specialist training. For subjects such as medicine, surgery, anesthesia and psychiatry, it has been suggested that the in-service reservation be increased to 50%. For subjects such as ophthalmology and ENT, where there is an excess of specialists, it has been recommended to completely do away with the in-service reservation scheme. It has also been suggested that the percentage of seats reserved for each subject be reviewed every 3 years and re-adjusted as per vacancies and requirements.(8)

Academic performance of in-service post-graduate students

Officials at the Directorate of Medical Education were concerned about the academic performance of in-service candidates in their PG programs. A look at the results of the final PG exam explains why [Table 6].

Table 6.

Academic performance of general and in-service candidates in their final year post-graduate examinations

In-service candidates have a much lower pass rate in the final year PG exams compared with the non-reservation students.(8) Among students too, there is agreement that those who come into the PG program through the in-service quota (who tend to be older) often struggle with their studies. As one student put it, “it is definitely a disadvantage, it is difficult for them to compete with youngsters. They have to think about their families.”

Lax enforcement of the bond to serve the state government

An administrative procedure for enforcing the bond exists in the rule book. The Dr. NTR University for Health Sciences (which administers the PG entrance examination and admission process) is the recipient of the surety. The department where the specialist is employed is instructed to receive the refund of the salary. However, there was little awareness about compliance or the process of enforcing the bond. There was no information on whether there were violators or how many had been booked. As one official put it, “most officers are not supervised about (the) bond due to the lack of a database.”

One reason for the lack of information on bond compliance is the lack of coordination among the three sections of the department, namely the Directorate of Health, Directorate of Medical Education and the Andhra Pradesh Vaidya Vidhan Parishad (APVVP), all of which play a role in the PG reservation program. This has hindered the collection of information on bond compliance and how well returning specialists have been able to serve specialist needs in rural hospitals.

Discussion and Conclusion

Findings from this study suggest that the PG reservation scheme in Andhra Pradesh has played a role in attracting medical graduates to government service and rural posts over the last few years. Increased competition due to the rapid expansion of undergraduate medical education has made the scheme more attractive than before. While it is difficult to establish causality, the available evidence suggests that the scheme has contributed to fewer vacancies in Medical Officer and specialist posts. By aligning its requirement for Medical Officers at PHCs with the high demand among medical graduates for PG seats, the government of Andhra Pradesh has been able to fill vacancies at the PHC level as well as increase the pool of specialists available in public sector hospitals.

The high growth of MBBS graduates coupled with the much slower growth in PG seats will ensure that the PG reservation scheme continues to be a powerful incentive to attract medical graduates and specialists to government service and rural areas.

There are several concerns about the scheme. Officials in the Health, Medical and Family Welfare department reported that Medical Officers and specialists who are brought to rural posts through the PG reservation scheme may not be performing their job well. This scheme has managed to place doctors in rural posts who might otherwise be disinterested in serving there. Placing a doctor in a rural health facility is a necessary but not sufficient condition for strengthening rural health services. In addition to successfully posting a doctor in rural areas, there need to be improvements in service conditions, namely better pay, better working and living conditions and substantial avenues for further career advancement.

A second concern is the mismatch between the number of graduating in-service students in each specialization and the governments’ requirements for specialists. Public sector needs are not matched with the number of seats reserved in different specialties through the PG reservation scheme. This has implications on the availability of specialists in government hospitals.

A related concern is the need to carefully calibrate MBBS and PG seats to fill vacancies. There is a perception in the health department that increasing the number of medical seats both at the MBBS and at the PG levels will help reduce specialist vacancies. However, increasing PG seats in the government sector may reduce the attraction of the PG incentive, if it eases the pressure on the entrance exam. While it may potentially lead to reduced vacancies at the specialist level (assuming mandatory rural service for newly graduated specialists), this may be at the cost of filling up vacancies at the PHC level.

A third concern is the apparent lack of oversight on how well graduating in-service students are serving public sector needs. There is no information on how many of these students break their bonds, if they pay the penalty of breaking the bond and where they are posted (or end up serving) when they re-join service. Producing and keeping regular track of this data will enable better management of the program.

The PG reservation scheme enjoys broad support from policy makers in the state. The increasing number of students taking up the scheme every year is proof positive of the scheme's appeal. Similar schemes are being adopted by many states in India as a way to fill rural Medical Officer and specialist posts. However, there are several issues that need to be addressed to make this scheme a powerful engine for strengthening rural health care in the country.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. B.V. Rao, Mr. B Prem Kumar, Dr. M V Ramanamma and Dr Sailaja Bitragunta at the Andhra Pradesh Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department for their inputs and assistance with information. Also we would like to thank Dr Shomikho Raha for his comments on the outline of the study and Dr Mala Rao, IIPH Hyderabad for guidance and support.

Author Roles: All three authors jointly conceptualized the study. Seema Murthy and Zubin Shroff collected the data and conducted interviews. The article was jointly prepared by all three authors.

Appendix 1: Views about the Post-Graduate Reservation Scheme in Andhra Pradesh

Easier admission to post-graduate programs for in-service students

‘… entrance is easy for in-service, in service is much easier (than for others)’ (PG Student)

‘… (PG Reservation scheme is) beneficial. Easy to get a PG seat. Both sides (benefit) government and students.’ (PG Student)

Reduced vacancies of medical officers at PHCs and specialists at CHCs

‘… just because of (this incentive) we have managed to hold 90% of the people who work in rural areas’ (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

‘… it did make a difference, the incentive makes a difference, service quota has really increased willingness to work’ (Public Health Specialist, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

‘… whenever we advertise for recruitment they do come in and they do join in rural areas if only for the PG seat’ (Public Health Specialist Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

‘… it [PG reservation scheme] is a good encouragement, it is the best incentive for doctors to go to rural areas, everyone aspires for higher education, everyone needs higher education in this competitive world’ (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

Academic performance of in-service post-graduate students

‘… it is definitely a disadvantage, it is difficult for them to compete with youngsters. They have to think about their families’ (PG student)

Lax enforcement of the bond to serve the state government

‘… they (medical officers) are going abroad, outside the district, somewhere else, working in private there is no real tracking mechanism’. (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

‘… most of officers not supervised about bond due to the lack of a database’ (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

‘… I don’t think anyone has paid the bond’ (Public Health Specialist Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

‘… why should they break the bond, they are sitting at one place and working somewhere else’ (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh)

Concerns about quality of care and suggestions for improvement

‘… most people interested in PG. Very few interested to do service in rural area.’ (PG Student)

‘… 85-90% do this only for PG’ ‘(earlier) without doctor no work, now with doctor no work’ (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh Health)

‘… (Doctors have to be made) responsible for their work, self-appraisal, some sort of supervision, some sort of good monitoring system, only if they have done well (during their time in-service) they should be sent for PG. Some system to monitor and evaluate whether they have worked satisfactorily for 2-3 years’(needs to exist) (Officer, Health, Medical and Family Welfare Department, Andhra Pradesh Health)

PG Reservation should be ‘linked it to some kind of performance measure’ (Public Health Specialist)

(in one case there were) ‘five doctors working 10 kms from the district headquarters, no doctor was staying in the PHCs and no doctor was attending the institution. (Official Health Department)

Footnotes

Source of Support: Global Health Workforce Alliance, WHO

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rao K, Bhatnagar A, Berman P. India's health workforce: size, composition and distribution. In: La Forgia J, Rao K, editors. India Health Beat. New Delhi: World Bank, New Delhi and Public Health Foundation of India; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medical Council of India, New Delhi. List of colleges teaching MBBS course. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/InformationDesk/MedicalCollegeHospitals/ListofCollegesTeachingMBBS.aspx .

- 3.Medical Council of India, New Delhi. List of colleges teaching PG courses. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 10]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/ InformationDesk/ForStudents/ListofCollegesTeachingPGCourses.aspx .

- 4.Dr. NTR University for Health Sciences, Vijayawada. [Last accessed on 2010 Nov 15]. Available from: http://59.163.116.210/colleges/Medical2.asp .

- 5.Bulletin of Rural Health Statistics 2009. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, government of India, New Delhi. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/Bulletin%20on%20RHS%20 -%20March,%202009%20-%20PDF%20Version/Title%20Page.htm .

- 6.Bulletin of Rural Health Statistics 2007, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, government of India, New Delhi. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 15]. Available from: http://mohfw.nic.in/Bulletin%20on%20RHS%20-%20March,%202007%20-%20PDF%20Version/Title%20Page.htm .

- 7.Bulletin of Rural Health Statistics 2008. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, government of India, New Delhi. [Last accessed on 2010 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/Bulletin%20on%20RHS%20 -%20March,%202008%20-%20PDF%20Version/Title%20Page.htm .

- 8.Directorate of Medical Education. Recommendations of Meeting on in-service reservation scheme September 2010 [Google Scholar]