Abstract

Objectives:

To determine an association between socioeconomic status and in-hospital outcome in Indian patients with stroke.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective hospital-based cohort study. The hospital stroke register was used for this study. The independent variables were demographic job status, education, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities and the score on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). The outcome variables were mortality and Barthel′s index (BI) score at discharge.

Results:

Data of 599 consecutive patients comprising 370 men (54.3%) and 229 women (33.6%) was available for analysis. Their mean age was 55.63±15.36 years. Age, diagnosis (ischemic or hemorrhagic), midline shift, smoking and GCS were significantly associated with mortality and BI score (P<0.05). There was a statistically significant association between employment status and BI at discharge (P=0.03) in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, joblessness was associated with lower BI at discharge (P=0.02) after adjustment for GCS motor score and stroke subtype.

Conclusion:

Our study shows that in patients with stroke, lower employment status is associated with poor outcome at discharge from the hospital. The association is independent of other prognostic factors.

Keywords: Socioeconomic status, stroke, mortality, morbidity

Introduction

Low socioeconomic status (SES) is an important factor that appears to increase mortality and disability in stroke. The relationship of SES with poor outcome after stroke has been shown.(1) SES is an important risk factor for stroke and ischemic heart disease, with the incidence and mortality of each increasing as SES declines. Studies in stroke are unable to provide a final answer to this question. Some studies show an association between lower SES and increased case fatality, but others do not.(1–4) This study was undertaken to find the association between the in-hospital outcome (mortality, functional disability) of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke with SES and its dependent factors, occupation and educational status of the patients admitted with stroke.

Materials and Methods

This study was based on a retrospective analysis of the hospital-based, stroke registry of patients from a mixed (urban and rural) population admitted to the neurology department at a tertiary care center in north India, which serves a huge community of people. Data of stroke was prospectively collected after obtaining informed consent from the patients who were admitted to the Department of Neurology between 1994 and 1998. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition of stroke was used for the diagnosis of stroke. The occupation was categorized into service (salaried), business and “others,” which mainly included people who were unemployed or those who were daily wages workers, unskilled labourers or farmers without their own land. We used a structured interview to assess the clinical and neurological variables (such as the score on Glasgow coma scale (GCS), Barthel′s index (BI) and modified Rankin scale (MRS) at admission and discharge), demographic factors, SES, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities. The outcome was evaluated by mortality, MRS, BI at discharge and GCS.

Statistical analysis

BI scores and MRS score of admission and discharge were used for evaluating the outcome. To study the significance of independent variables in the prognosis, single-variable logistic regression analysis was employed. To study the simultaneous effect of different variables on recovery, multiple regression analysis was used employing the SPSS 13 statistical package.

Results

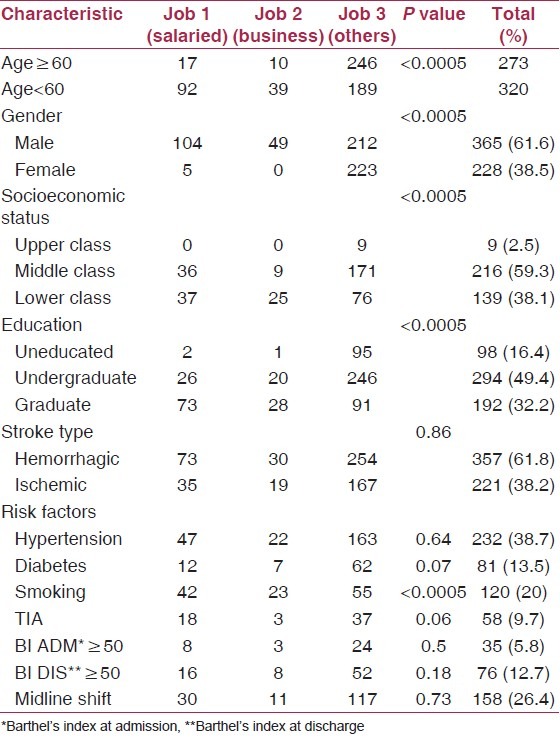

Between 1994 and 1998, a total of 682 patients with suspected stroke were registered. Of these, data of 599 patients was analyzed and 83 were excluded due to incompleteness of data. Their mean age was 55.6 ± 15.4 years, of whom 370 (54.3%) were men and 229 (33.6%) were women [Table 1]. Maximum number of patients belonged to the middle class (58.9%). About 73.2% of the patients belonged to the “others” category. The number of patients with hemorrhagic stroke was 227 (38.9%) and ischemic stroke was 357 (61.1%). The mean BI was 35.8 among all age groups. Patients with lower occupation category had poor mean BI at admission (26.59) as compared with people of the service class (40.36) and business class (40.56).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the various job categories

Diagnosis (ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke), midline shift and GCS were significantly associated with mortality and complications (P < 0.05) [Table 2]. Employment status was significantly associated with MRS at discharge (P = 0.001) and BI at discharge (P = 0.03) in univariate analysis.

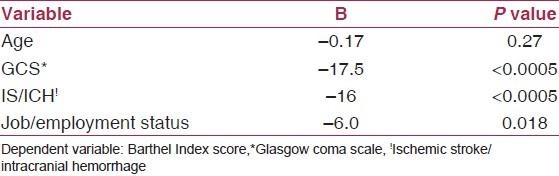

Table 2.

Multiple regression analysis after adjustment with other cofactors

In multiple regression analysis, employment status was negatively correlated with BI at discharge (r=-0.2; P = 0.02). BI at discharge was also noted to have a negative correlation with GCS (r = 0.52; P < 0.005) and diagnosis (ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke) at admission [Table 2].

Discussion

In the present study, we found that unemployment and lower occupational status was associated with poor in-hospital outcome as measured by BI at discharge and MRS at discharge. There is no national or international data of the effect of SES on in-hospital mortality.(1,5)

Observations from Canada showed that the 30-day and 1-year mortality was higher in the lowest income quintile than in the highest income quintile.(1)

Similar results were found in a Finnish study (FINMONICA stroke registry), although other studies found that education is not related to survival, but both occupation and income have an independent effect on risk of death after stroke.(2,4,6–8) We found a negative correlation between employment status and GCS at admission as well as with employment status and BI at discharge, supporting these observations and suggesting that low job status is a risk factor for poor in-hospital outcome of stroke.

The reason for low GCS motor score at admission in our study could be, firstly, referral bias of the patients with low SES and low GCS to the government hospitals; secondly, higher prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes in this group; thirdly, delay in arrival to the hospital; and, lastly, severe stroke.

Our study shows that in patients with stroke, lower employment status is associated with poor outcome at discharge from the hospital. The association is independent of other prognostic factors.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kapral MK, Wang H, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Effect of socioeconomic status on treatment and mortality after stroke. Stroke. 2002;33:268–73. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakovljević D, Sarti C, Sivenius J, Torppa J, Mähönen M, Immonen-Räihä P, et al. Socioeconomic status and ischemic stroke: The FINMONICA stroke register. Stroke. 2001;32:1492–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.7.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aslanyan S, Weir CJ, Lees KR, Reid JL, McInnes GT. Effect of area-based deprivation on the severity, subtype, and outcome of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2623–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000097610.12803.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peltonen M, Rosén M, Lundberg V, Asplund K. Social patterning of myocardial infarction and stroke in Sweden: Incidence and survival. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:283–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weir NU, Gunkel A, McDowall M, Dennis MS. Study of the relationship between social deprivation and outcome after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:815–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157597.59649.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rossum CT, van de Mheen H, Breteler MM, Grobbee DE, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic differences in stroke among dutch elderly women: The rotterdam study. Stroke. 1999;30:357–62. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arrich J, Lalouschek W, Müllner M. Influence of socioeconomic status on mortality after stroke: Retrospective cohort study. Stroke. 2005;36:310–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000152962.92621.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weir NU, Gunkel A, McDowall M, Dennis MS. Study of the relationship between social deprivation and outcome after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:815–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157597.59649.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]