Introduction

To the epidemiologist, the most important event and the least equivocal measure of health is death, which could be called the absolute opposite of health.

Mortality statistics reveal much about the health of the population: Ones derived statistics and life expectation at birth and at various subsequent ages is often cited as an indicator of population health when comparisons are made over time and between nations for designing intervention programs, allocation of resources and indicating priorities. It is essential to know the frequency of disease or death. But this is not static, and is changing. It is also important to decide whether the observed change reflects change in incidence, in case fatality or both. It is equally important to determine whether that observed trend in mortality is genuine or is it due to change in nomenclature or classification of disease, changes in accuracy of diagnosis or changes in the statistical classification or allocation of priorities.(1)

Traditionally and universally, most epidemiological studies begin with mortality data, which is relatively easy to obtain and, in many countries, reasonably accurate. Many countries have routine systems for collection of mortality data and causes of death are important and widely used for number of purposes they may employ in explaining trends and differentials in overall mortality, indicating priorities of actions and in the assessment and monitoring of public health.(2)

Although diseases have not changed significantly through human history, their patterns have. It is said that every decade produces its own pattern of disease.

The pattern of diseases in developing countries is very different than those in developed ones. In a typical developing country, most deaths result from infectious and parasitic diseases, abetted by malnutrition. In India, about 40% of deaths are from infectious, parasitic and respiratory diseases as compared with 8% in developed countries. Diarrheal diseases are widespread. Cholera has shown a declining trend. Malaria and kala azar, which showed a decline in the 1960s, have staged a comeback. Japanese encephalitis and meningococcal meningitis have shown an increasing trend. There is no appreciable change in the prevalence of tuberculosis, filariasis, viral encephalitis diarrheas and dysentery and disorders of malnutrition and under nutrition. On the other hand, an increase in the frequency of new health problems such as coronary heart disease hypertension, cancer diabetes and accidents has been noted.(2)

The Medical Records Department in a teaching hospital has a system of compilation and retention of records; yet, the acquisition of meaningful statistics from these records for health care planning and review is lacking. Mortality data from hospitalized patients reflect the causes of major illnesses and care-seeking behavior of the community as well as the standard of care being provided. Records of vital events like death constitute an important component of the Health Information System. Hospital-based death records provide information regarding the causes of deaths, case fatality rates and age and sex distribution, which are of great importance in planning health care services. There is a paucity of information about direct causes of child mortality in developing countries.(1) This information also provides the basis for patient care and helps the administration in managing day-to-day hospital affairs. The present study was aimed to study the trend and mortality pattern in a tertiary care hospital and an attempt was made to determine whether epidemiological transition is present in mortality data.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis was done with records of patients who died in Shree Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Sarvopachar Rugnalaya, a tertiary care hospital attached to Dr. V.M. Govt Medical College, Solapur, Maharashtra. All case records of indoor patients after discharge or death, except deaths of medico legal cases, are submitted in the Medical Record Section that works under the Department of P.S.M. of Dr. V.M. Medical College, Solapur. All deaths that occurred during the 5-year period, i.e., 2005-2009, except medico legal deaths, were considered for analysis. Case sheets of deaths for years 2005-2009, i.e., the 5-year period, were analyzed to study the trend and pattern of disease causing deaths. The underlying cause of death was recorded with great accuracy and was classified as the I.C.D. 10th revision. Name, age, sex, date of admission, place of residence, date of death and underlying cause of death were used for analysis.

Results

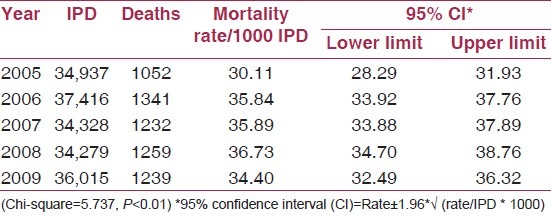

In 5 years, i.e., from 2005 to 2009, a total 6123 deaths were registered in the Medical Records Section. Mortality rate per 1000 indoor admissions was calculated. It was less in 2005 and increased in 2006 and remained stable till 2009. The mortality trend was studied, which was linear, and was statistically significant (χ2 = 5.737, P = 0.01). The linear trend equation was calculated [Table 1].

Table 1.

Year-wise mortality rate

The trend line equation for mortality rate is Y = 34.59 + 0.0547× (X - 2007)

where Y= mortality rate, X= year

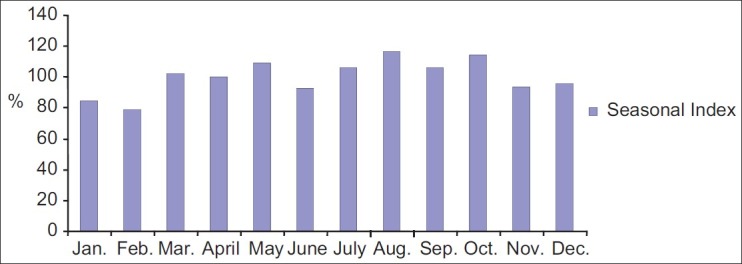

Maximum deaths were seen in the month of August in all 5 years, and minimum were seen in February. The seasonal index of mortality was maximum in the rainy season, i.e., in the months of July-August-September-October, followed by the summer season, i.e., in the months of March-April-May. It was minimum in the winter season, i.e., November-December-January-February in all 5 years [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Month-wise seasonal index of deaths in 2005-2009

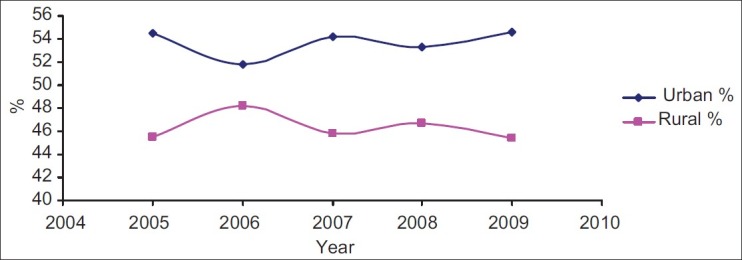

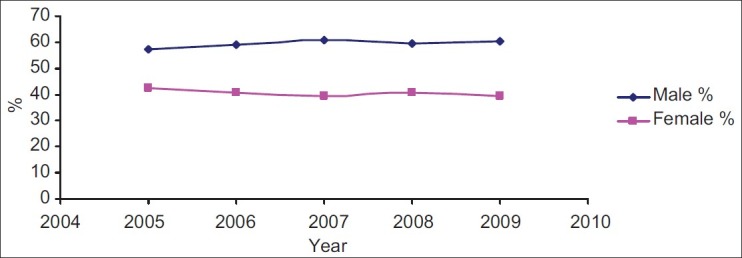

Consistently, urban deaths were more than rural deaths, which may be due to easy accessibility in emergency conditions for severe and moribund patients in the urban area in all the 5-years period [Figure 2]. Male deaths were more than female deaths during 2005-2009, and the difference was statistically significant. Sixty percent of the deaths were in males and 40% in females [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Year-and place-wise distribution of deaths

Figure 3.

Year-and sex-wise distribution of deaths

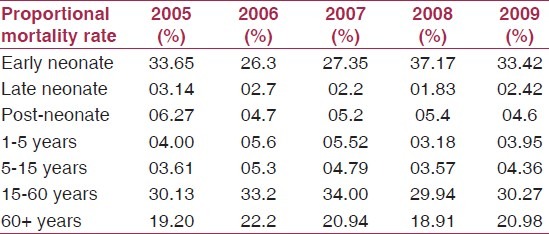

The major proportion of hospital deaths were seen in the early neonatal period, which were maximum in 2008 (37.17%) and minimum in 2006 (26.3%). Late neonatal deaths were very less. Nearly 1/5 of the hospital deaths were in patients aged 60 years and above (18.91- 22.2%). The proportional mortality rate for adults, i.e., for patients aged 15-60 years, was in the range of 29.94-34%. It was maximum in 2007 (34%). The proportion of infant deaths was in the range of 33.75-44.4%, and was maximum in 2008 and minimum in 2006 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Proportional mortality rate by age in 2005-2009

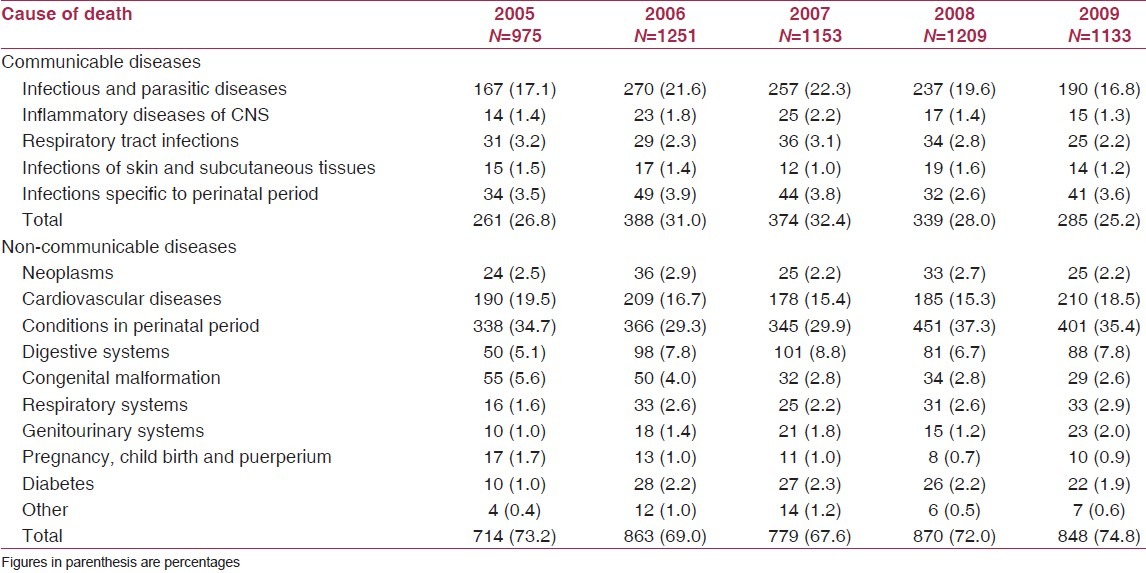

Cause of death was coded as per the I.C.D 10th revision, and 975, 1251, 1153, 1209 and 1135 deaths for the years 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 and 2009 were coded, respectively, and nearly 6-7% deaths could not be classified due to some technical difficulties. Joshi et al. mentioned that 18% of the deaths could not be classified.

In the 5-year period, i.e., from 2005 to 2009, the proportion of deaths due to communicable diseases showed a declining trend from 2006 to 2009. It ranged from 25% to 32% in these years, while the proportion of deaths of non-communicable diseases showed an increasing trend. The range was from 68% to 74.9%. Maximum proportion of non-communicable diseases (NCD) was in 2005 and 2009. Among the communicable diseases, the most common cause of death was tuberculosis (39.7-47.8%), followed by infection specific to the perinatal period (9.44-14.4%). Among the non-communicable diseases, the most common cause of death was conditions originating in the perinatal period, such as prematurity and low birth weight excluding infections in the perinatal period (42.4-51.8%), followed by cardiovascular diseases and diseases of the digestive system (21.3-26.6%) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Year-wise deaths of communicable and non-comminicable diseases

Discussion

In the present study, the mortality trend was linear for the period 2005-2009. A similar finding was reported by Joshi et al.(3) A log linear increased death rate for aged men and women from 5 years of age was seen. Last(1) mentioned that the mortality trend with time was usually either upward or downward, and a seasonal trend of deaths was observed in the present study, but was not seen by Roy et al.(4)

Preponderance of male deaths (60%) over female deaths, similar to the present study, was a finding of many authors.(1–10)

The age curve of mortality has general features in common everywhere, with variation depending upon environmental factors. Mortality is high during the first year of life, which drops to the lowest level in childhood and then gradually begins to climb during the third and fourth decades,(1) which is very well documented by the present study. Highest neonatal mortality was found by some authors.(4,7)

The significant decline in early neonatal mortality found by Verma et al.(11) is different from the finding of the present study, where proportionate mortality rate for early neonate increased from 2006 to 2009. Infant deaths were less in various studies.(8–10) Pediatric deaths in the present study were 44.6-51.15% in the 5-year period, which were more than that reported by other authors(6,9–12) but similar in the study of Luiz Cesar Peres.(7) Deaths in patients of the age 15-60 years were nearly similar in the CRS report(9) but more (57%) in the report by Bhatia et al.(10) But, a similar proportion of deaths in patients aged 60 years and above was noted.

Chronic non-communicable diseases are assuming increasing importance among the adult populations in both developed and developing countries. They are the leading causes of deaths and there is an upward trend of non-communicable diseases due to many reasons such as change in lifestyle and behavior.(2) The present study also reveals epidemiological transition where proportion of non-communicable deaths were increasing in 5 years (68% in 2007 to 74.85% in 2009). The average proportion of deaths by NCD were 71%, which is similar to that in developed countries like Europe and America.(2) Co-existence of the disease pattern of both industrialized and developing countries indicating epidemiological transition similar to the present study was seen by Luiz Cesar Peres.(6) He found the percentage of cardiovascular deaths to be 21.3%, infectious and parasitic deaths to be 19.2%, gastrointestinal tract (GIT)-related deaths to be 6% and congenital malformation nearly similar to the present study, but perinatal deaths (10.8%) were less and neoplasm (12.8%) and respiratory system deaths (6.6%) were more than in the present study. In a review study of pediatric deaths by Luiz cesar Peres,(7) more perinatal deaths (51.0%) more congenital malformation deaths (24.4%) and less infectious and parasitic deaths (11.9%), less GIT and similar chronic non communicable diseases (CND) and cancer deaths were found. Omran(13) found a changing pattern of disease and a high prevalence of deaths due to infectious and parasitic diseases probably due lower socioeconomic status similar to the present study. But, cardiovascular deaths ranked second in his study. Bhatia et al.,(10) Mari Bhat,(14) Yang et al.(15) and Saha et al.(5) found that the percentage of communicable deaths was decreasing and that of non-communicable deaths was increasing, a finding similar to the present study.

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to Dr. Mrs. A. P. Kumavat, Prof. and Head, Department of PSM, Dr. V. M. Govt. Medical College, Solapur and Dr. S. S. Todkar lecturer and Mr. Wasim Bennishirur Statistician Medical Record Section for help during the conduct of this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Last John M, Rosenau M. Public health and preventive medicine. 11th ed. New York: Appleton Century Crofts; 1980. pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park K. Park's textbook of preventive and social medicine. 21st ed. 1167 Prem Nagar, Jabalpur, 482001 (M.P.), India: M/s Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; p. 42. & 52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshi R, Cardona M, Iyengar S, Sukumar A, Raju CR, Raju KR, et al. Chronic diseases now leading cause in rural India-mortality data from the Andhra Pradesh rural health initiative. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1522–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy RN, Nandy S, Shrivastava P, Chakraborty A, Dasgupta M, Kundu TK. Mortality pattern of hospitalized children in a tertiary care hospital of Kolkata. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:187–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.42062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha R, Nath A, Sharma N, Badhan SK, Ingle GK. Changing profile of diseases contributing to mortality in resettlement colony of Delhi. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:125–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peres LC, Ribeiro-Silva A. The Autopsy in a tertiary teaching hospital in Brazil. Ann clin Lab Sci. 2005;35:387–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peres LC. Review of pediatric autopsies performed at a university hospital in Ribeirão Preto, Brazil. Arch pathl lab Med. 2006;130:62–8. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-62-ROPAPA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar R, Sharma SK, Thakur JS, Lakshmi PV, Sharma MK, Singh T. Association of air pollution and mortality in the Ludhiyana city of India: A time-series study. Indian J Public Health. 2010;54:98–103. doi: 10.4103/0019-557x.73278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Civil Registration system. [Last accessed on 2011 Jan 01]. Available from: http://www.bhj.org/Journal/200-201/Origional-147.htm .

- 10.Bhatia S, Gupta A, Thakur J, Goel N, Swami H. Trends of cause-specific mortality in union territory of chandigarh. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:60–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.39250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma M, Chhatwal J, Chacko B. Perinatal mortality at a tertiary care hospital in Panjab. Indian J of pediatr. 1999;66:493–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02727154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalal SR, Jadhav MV, Deshmukh SD. Autopsy study of pediatric deaths. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:23–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02723770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omran AR. The epidemiological transition. A theory of the epidemiology of population change. 1971. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:161–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhat M. Emerging trends in mortality in India. Paper 2006. [Last accessed on 2012 Jan 17]. Available from: http://www.demorg.mpg.de/papers/workshop/020619 .

- 15.Yang G, Kong L, Zhao W, Wan X, Zhai Y, Chen LC, et al. Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372:1697–705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]