Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is progressive joint disease characterized by joint inflammation and a reparative bone response and is one of the top five most disabling conditions that affects more than one-third of persons > 65 years of age, with an average estimation of about 30 million Americans currently affected by this disease. Global estimates reveal more than 100 million people are affected by OA. The financial expenditures for the care of persons with OA are estimated at a total annual national cost estimate of $15.5-$28.6 billion per year. As the number of people >65 years increases, so does the prevalence of OA and the need for cost-effective treatment and care. Developing a treatment strategy which encompasses the underlying physiology of degenerative joint disease is crucial, but it should be considerate to the different age ranges and different population needs. This paper focuses on different exercise and treatment protocols (pharmacological and non-pharmacological), the outcomes of a rehabilitation center, clinician-directed program versus an at home directed individual program to view what parameters are best at reducing pain, increasing functional independence, and reducing cost for persons diagnosed with knee OA.

KEY WORDS: Arthrocentesis, hydrotherapy, musculoskeletal disorders, neuromuscular efficiency, osteoarthritis, pharmacological, quadriceps, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index scale

More than 20 million people in the US suffer from knee osteoarthritis (OA). By 2030, 20% of Americans (about 70 million people) >65 years of age are at risk for OA. Global statistics reveal over 100 million people worldwide suffer from OA, which is one of the most common causes of disability.[1,2] In addition, younger individuals may be susceptible to injury-induced OA. More than 50% of the population around the world (>65 years) show X-ray evidence of OA in one of the joints, thus demonstrating the high incidence of this disease. While OA is equally present in men and women, it appears to be more common among younger men (<45 years) and in the older women (>45 years).[3–6] As per a recent report published in the Times of India (2010) regarding OA, over 40% of the Indian population in the age group of 70 years or above suffer from OA. Nearly 2% of these undergo severe knee pain and disability. As per a recent statement quoted by Piramal Healthcare Limited in a nationwide campaign against chronic diseases, “India is expected to be the chronic disease capital, with 60 million people with arthritis, by 2025. The government, the private sector, the medical fraternity and NGOs should come together against the onslaught of chronic diseases.” Also, majority of those suffering from OA are deprived of access to quality treatment.[7]

Between the ages of 30 and 65 years, the general incidence and prevalence of knee OA has been reported to increase by as much as 10 times that of younger age groups, affecting nearly 33.6% of people >65 years or an incidence of 1 in 10.[8,9] Persons aged >65 years are more commonly affected by knee OA, due to the ongoing drop in birth rates and the overall increase in life expectancy; there is an alarming trend for future growth in the prevalence of knee OA in older population to be seen.[8] Along with the increase in age, there is an exponential increase in the associated risk factor of obesity, due to progressive sedentary behavior, changes in lifestyle patterns, diet routine, and work environment conditions among the adult population.[10] Currently 80% of persons affected by OA already report having some movement limitation, and 20% report not being able to perform major activities of daily living; with an 11% of the total affected population reporting the need of personal care.[6,8]

To study the prevalence of knee OA in women aged ≥40 years, some researchers performed a community-based cross-sectional study in an urban resettlement colony in South Delhi. OA was diagnosed by using clinical criteria given by American College of Rheumatology for diagnosis of idiopathic OA of knee joints. A total of 260 women were interviewed, of whom 123 (47.3%) women were found to be suffering from knee OA. Prevalence of OA was found to increase with age. Less than half of those with OA underwent treatment. With a high prevalence of OA, there is need to spread awareness about the disease, its prevention, and rehabilitation in the community.[11]

Etiology and Disease Diagnosis

OA can be seen as a two-part degenerative, chronic, and often progressive joint disease. It is the most common musculoskeletal complaint worldwide and is associated with significant health and welfare costs.[1] Within a joint such as the knee, there is a smooth fibrous connective tissue known as articular cartilage. This cartilage surrounds the bone where it comes into contact with another bone. In a normal joint, the cartilage acts as a shock absorber as well as it allows for even movement of the joint without pain. When cartilage degrades, it becomes thinner and may even disappear altogether leading to joint pain and difficulty in movement such as in knee OA. OA is characterized by a repetitive inflammatory response of the articular cartilage due to focal loss or erosion of the articular cartilage and a hypertrophy of osteoblastic activity or a reparative bone response known as osteophytosis.[10] Both of these defining characteristics result in a joint space narrowing or subchondral sclerosis, leading to pain, immobility, and often disability.[8,12] The symptoms of OA, such as pain and stiffness of the joints and muscle weakness, are serious risk factors for mobility limitation and lead to impaired quality of life for the affected population.[4]

To diagnose OA, the clinician might assess the nature and severity of the pain. It can also be diagnosed to measure the amount of movement in the joint. An X-ray of the knee-narrowing of the joint space is a good indicator of OA. Bony spurs can also be seen on an X-ray. In some cases, for further clarity and better diagnosis, the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be necessary. This allows the clinician to see whether any damage to the soft tissue has taken place within the joint. In certain cases, a blood sample may be necessary to rule out the presence of other types of types of arthritis.[13]

With statistics showing that more of the population will be affected by knee OA, there is an inbuilt need to consider what are the most relevant, cost effective, and appropriate care strategies to be implemented at tackling such a soon-to-be widespread problem. Currently the annually estimated cost per year to treat OA ranges from $15.5 to $26.6 billion, with some researchers estimating these figures to be much lower and the total cost is actually believed to exceed $89.1 billion in the near future.[6,10] Not only is OA costly to the affected individuals as an estimated per capita out-of-pocket expenses can be up to $2600, but also OA comes with a host of negative effects toward an individual's quality of life (QOL) and limited mobility related issues associated with severe pain, which have been found to be significant in affecting the treatment outcomes for this population.[8,13]

The present paper discusses the causes of knee OA, along with the different exercise and treatment protocols (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) currently available. It also focuses on the outcomes of a rehabilitation center clinician-directed program versus a home-directed individual program to view what parameters are best at reducing pain, increasing functional independence, and reducing cost in persons diagnosed with knee OA. The authors have tried to study the work of various research groups and different rehabilitation/treatment strategies being applied for the treatment of knee OA in this direction till date.

Knee Osteoarthritis: A Mystery Riddle

Despite numerous studies conducted, the etiology, onset, and specific causes for OA remain unknown. Scientists believe that a combination of physical factors such as obesity, aging, and joint injury coupled to genetic predisposition ultimately predispose some individuals to earlier onset of disease. What we do know is that repetitive mechanical loads, age, and high levels of inactivity play the most important role in the development of OA;[13,14] therefore, taking a careful consideration of the age, activity level, and diagnosis of the patient/client is critical in developing a plan of care for most clinicians. As there is no known cure for OA, current treatment aims at controlling pain, and improving function and health-related quality of life.[15] It is well known that OA is characterized physiologically by loss of cartilage covering the joints, leading to direct bone to bone contact.[16] Such a situation results in a high degree of pain in the affected joint and thus restricts mobility. In cases of advanced OA, only a total joint replacement can provide relief; however, we note that many patients are not candidates for joint replacements, as the surgery is highly invasive and secondly, the procedure is extremely expensive.[2]

Symptoms of OA can vary between individuals. Some patients may be incapacitated by the disease, while others, despite the severity based on X-rays, perform normal activities with little or no pain. Knee OA is most commonly found in people who play intense physical sports requiring severe strain and loading on the joints, such as American football, soccer, rugby, gymnastics, etc., Prior injury is a major indication toward future development of the disease. Another major cause of knee OA is often associated with obesity in the upper extremity, leading to heavy weight bearing of the knee.[15] Progressive cartilage degeneration of the knee joints can lead to deformity which may lead to outward curvature of the knee, referred to as “bowlegged.” People with OA in the knee can then develop a limp which can worsen as more and more cartilage degenerates with time. Degenerative changes in the knee joint are also thought to increase postural sway.[17,18] In some patients, the pain, limping, and joint function do not respond to medications, therefore more extreme measures need to be taken to fix the problem, such as total knee replacement. In cases of advanced OA, only a total joint replacement can provide relief; however, as stated earlier, many patients are not candidates for joint replacements.[2,19]

Knee OA can be diagnosed by several techniques including medical imaging. X-ray findings of OA include loss of joint cartilage, narrowing of the joint space between adjacent bones, and bone spur formation. X-ray can also be used to exclude other causes of pain in a particular joint, as well as in assisting physicians in decision-making during surgical intervention. Another technique to diagnose OA is arthrocentesis. This procedure is used to remove joint fluid and is often performed in the doctor's office. During arthrocentesis, a sterile needle is used to remove joint fluid for analysis. This is useful in excluding gout, infection, and other causes of arthritis. Also, during the procedure, removal of joint fluid and injection of corticosteroids into the joints may help relieve pain, swelling, and inflammation. Additionally, an athroscopy technique may be used by the doctor to insert a viewing tube into the joint space to detect and repair any abnormalities or damage to the cartilage and ligaments through the arthroscope. If the method is successful, patients can recover from the arthroscopic surgery much more quickly than from an open joint surgery.[8] OA can affect either one (unilateral) or both (bilateral) sides of the knee, but is most commonly found in the inner (medial) compartment of the knee joint.[18,19] A well-known format to classify osteoporotic severity and standardize it across many individuals is the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scale. WOMAC is a disease-specific, self-administered, health status measure. It classifies symptoms in the areas of pain, stiffness, and physical function in patients with OA of the hip and/or knee. The index consists of 24 questions and is usually completed in 10-15 min. The WOMAC scale reads from 0 to 10 in order from less severe to most severe OA condition.[5]

Treatment and Management

From the current studies available, no specific cure for OA exists and the severity of condition varies from individual to individual. Hence, a more generic approach to current treatment methods revolves around some combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment modalities. Mostly, all exercise programs for knee OA should be practical, albeit simple, but should be helpful in gradual and progressive cure of the condition. Each program should be individually designed for proper accommodations based on the severity, age, gender, weight, lifestyle, and the individual's functional capabilities.[10,20] These program settings should typically not involve any high-impact axial loading and should allow for proper rest intervals as set forth by the individual's needs toward the frequency, intensity, and duration of the treatment. The goal of the program should be to decrease pain, increase the range of motion, increase the overall functional strength, educate about posture and gait, as well as to improve physical fitness levels and mobility.[15,21] The different treatment modalities currently being employed for treatment and management of OA are discussed subsequently in detail.

Non-pharmacological treatment modalities

In this section, the currently available different non-pharmacological treatment modalities for cure of OA are discussed. Weight reduction is one of the first and unproblematic measures that can be taken to reduce knee OA. Studies of OA have constantly shown that overweight people have higher rates of knee OA than non-overweight control subjects. This is due to the fact that force across the knees is 3-6 times the body weight; therefore, people who have more mass cause extreme forces on their knees, leading to the early onset or steady progression of knee OA condition.[22] Individuals who are overweight may have circulation problems, possibly including a cartilage growth problem or a bone problem, which has the ability to cause cartilage breakdown or affect the bone underneath the cartilage, thereby leading to OA. Finally, overweight people have higher bone mineral densities, and high bone mineral density (or the absence of osteoporosis) may itself be a risk factor for OA.[9,23] Weight loss is therefore a logical step to relieve pain in these joints and to slow the progression of degenerative arthritis. According to a study conducted by Mao-Hsiung Huang and group, pain reduction and improvement of walking speed in various degrees of severity of arthritis was observed in the OA population undergoing prescribed weight loss procedures.[22]

Apart from weight reduction and avoiding activities that exert excessive stress on the joint cartilage, there has been no specific treatment to prevent cartilage degeneration or to repair damaged cartilage in OA. Therefore, for the past several years, research has focused on determining the causes of knee OA and to discover how to stop the progression of the disease, aside from lowering the effects such as pain and discomfort by therapy.[1,3,6] Some studies have even hoped to help reform the lost cartilage to return the knee back to health. A potential technique that can augment cartilage growth (stem cell tissue engineering approaches) is the use of electromagnetic field therapy (EFT). Modulation of cell signaling events by weak electromagnetic fields is associated with binding of hormones, antibodies, and neurotransmitters to their specific binding sites.[24] Pulsed electromagnetic fields (PEMF) treatment preserves the morphology of articular cartilage and retards the development of OA lesions.[25] However, while supply limitations of stem cells can be overcome, the lack of tissue quality, specifically in the preparation of the differentiated stem cells toward the articular cartilage phenotype is still a major challenge for the researchers.[26]

However, the most widely used remedy for knee OA is rehabilitation and physical therapy (PT). PT has proved to be useful in helping patients with pain and mobility.[14,15] Fitness walking, aerobic exercise, and strength training have all been reported to result in functional improvement in patients with OA of the knee.[27] Having a clinical PT program has the benefits of onsite direction and availability of sophisticated equipment.[28] By and large, various studies[12,20,29] have shown that having these added benefits contributes to program adherence and overall higher outcomes while in the care of the PT.[12] These programs may be divided into PT at rehabilitation center under the supervision and monitoring of doctors and trained specialists and the other one carried out through personal care as prescribed by medical practitioner at home.

Rehabilitation-centered approach

The specific programs that are typically run are a combination of programs such as strength training, aquatic, Tai Chi, aerobic, and hydrotherapy.[21] Strength training, being the most common treatment approach for the management of patients with functional limitations, is prescribed to address the need to increase muscular strength and joint stability for improving in WOMAC pain scores and overall health benefits.[20,30] The common equipment used is based on fundamentally different movement progression and resistance patterns such as isotonic (unchanged tension but change in length), isometric (no change in length or angle), and isokinetic (constant resistance with variation in speeds).[20,30] Though isometric activities show effective results in reducing pain levels, they are avoided when working with the elderly due to increases seen in heart rate and blood pressure, which could be contraindicative to other co-morbidities.[30] Typically the programs last for 6-24 weeks with an average of 8 weeks, while working at an average frequency of three sessions per week for an average duration of 30 min each.[21,31] Studies structured like the one above scored overall 80% decreases in pain, a considerable decrease in crepitus (P < 0.01), increase in isokinetic hip flexor, adductor, and abductor angular velocity (degree/sec), as well increases in overall isotonic and isometric strength.[21,30]

Tai Chi [Figure 1] is a Chinese martial art that is primarily practiced for its health benefits, including a means for dealing with tension and stress. It emphasizes complete relaxation, and is essentially a form of meditation, or what has been called “meditation in motion.” Unlike the hard martial arts, Tai Chi is characterized by soft, slow, flowing movements that emphasize force, rather than brute strength. Though it is soft, slow, and flowing, the movements are to be executed precisely. Tai Chi as a form of therapy was typically conducted within the clinical setting and followed a host of different focus styles (Sun, Wu, Yang, Baduanjin, and Qigong), all of which were used as an intervention protocol for hip and knee OA.[21] Each Tai chi session on average ran a length of 8-24 weeks with a frequency of one to five sessions per week at a length of 20-60 min. The use of Tai Chi showed significant improvements in reducing pain levels, and ultimately good program adherence.[21,31] Out of all the styles selected, the Yang style (comprising 13 basic body movements) proved to have the best results.[31]

Figure 1.

Tai Chi exercise program (Reprinted with permission from[32,33])

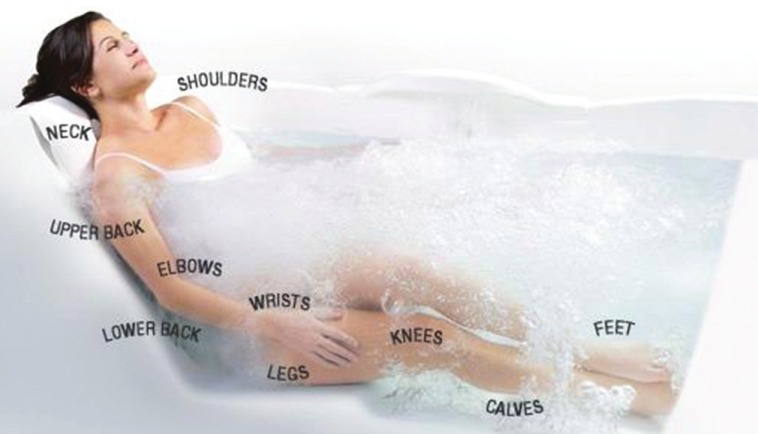

Hydrotherapy (balneotherapy) involves the use of water in any form or at any temperature (steam, liquid, ice) for the purpose of healing [Figure 2]. In aquatic physical therapy, or hydrotherapy, exercise activities are carried out in heated pools by a variety of providers.[34] Hydrotherapy/balneotherapy and aquatic therapy [Figure 3] displayed positive results, when conducted for testing subject's strength and flexibility. The results emphasized the role of these therapies in aiding normal walking and relieving joint pain.[21,35] The sessions typically are run from 6 to 48 weeks for duration of 60 min, and are conducted in a shallow pool with water temperatures ranging from 29°C to 34°C.[21]

Figure 2.

Hydrotherapy/balneotherapy (Reprinted with permission from[33])

Figure 3.

Aquatic exercises (Reprinted with permission from[33])

Aerobic exercise [Figure 4] programs may make OA patients feel better, help reduce the joint pain, and make it easier for them to perform daily tasks. Exercise programs under medical supervision should be balanced with rest and joint care.[36] Aerobic programs truly border both clinical (rehabilitation) and home programs. Regardless of the setting, this program type was found to be effective for reducing pain in hip and knee.[29,36] Patients are typically recommended to exercise between 50% and 70% target heart rate for a minimum of 30 min, 3 times a week, for overall weight management, health benefits, and a reduction in pain which was noted after a 6-month program.[21]

Figure 4.

Aerobic exercises (Reprinted with permission from[33])

At home centered programs

Home programs are often followed due to the extremely high demand and cost for public health services which otherwise would go unanswered due to a host of barriers, travel and cost being the two predominant ones.[13,28] A significant reduction from baseline in activity related pain (visual analog pain scale) and improvement in functional tasks like self-paced walking (SPW) and stepping (SPS) test time, passive range of motion, and physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE) were noticed after 8 weeks in both exercise and sham groups. However, these changes were significantly greater (P < 0.05) in the exercise versus sham group.[37] Home programs have been noted to work best when complemented with return to the clinical setting every 2 weeks for re-evaluation or reassessment and program assessment for maintaining optimal results from the program.[10,36] Home programs are noted to gap the regular visits to clinician by means of printed self-assisting manuals[13,38] which are easy for referring to stretching/strengthening (isotonic and isometric) exercise images and other information such as proper use of analgesic measures like cryotherapy and compression. Most people do not realize that common daily activities such as walking, gardening, swimming, or dancing are great outlets for adherence to the home physical exercise program.[29] The key when providing the home-centered approach is cost effectiveness and quality of care based on quality research outcomes.[36]

Yoga therapy for osteoarthritis rehabilitation

Although many people think yoga involves twisting the body into pretzel-like poses, it can be safe and effective for people with OA. Yoga's gentle movements can aid to build body strength, flexibility, and balance, and reduce arthritis pain and stiffness. The slow, controlled physical movement of joints is helpful for the arthritis patients. It improves the blood circulation in joints, removing unwanted toxins and other waste products. However, the problem is if the patient tries to move his limbs and joints then pain increases, which may lead to task avoidance, thereby further increasing the problem. So, it is a vicious cycle, i.e., because of pain no movements and because there is no movement, the situation becomes even worse. So, the patient should keep doing the movements which are possible for him/her. A pilot study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine, examined one type of yoga, Iyengar yoga, suitable for people with OA of the knee. After an 8-week course of weekly 90-min beginner classes, there was a statistically significant reduction in pain, physical function, and mood, indicating the positive effects of yoga therapy for OA rehabilitation.[32]

Outcomes of rehabilitation centered approaches

Based on the different types of PT-based rehabilitation care provided for improvement of knee OA condition, it is quite evident that they work best when combined as reported, to improve functional task performance and decrease the level of associated pain.[36] However, the effects are seen greater in the groups of patients receiving clinical based care, but are rapidly diminished after a year of an at home care regiment program as many times the patients do not adhere to specified routine or other prescribed treatment care, which is a cause of neglect.[29,38]

PT has shown to be both clinically and statistically significant.[8] It showed improvements in 6-min walk distance and WOMAC score at 4 and 8 weeks in the treatment group but not in the placebo group.[29] These interventions resulted in less pain and joint stiffness and greater physical function, improvement in quality of life, and hip muscle strength. About 72% and 75% of participants reported improvements in pain and function, respectively, compared with only 17% (each) for control participants.[39]

Although PT has proven to be a useful treatment for knee OA, studies have been conducted to determine the role and functioning of different muscle groups in patients with knee OA compared to healthy patients. This is done in order to determine which muscles need particular attention and care during PT for improving the pathological condition of knee OA patients. When the musculoskeletal study began in 2006, researchers measured the strength of participant's quadriceps muscles (leg muscles in the upper thigh). Analyzing these, researchers observed that participants having greater quadriceps strength had less cartilage loss within the lateral compartment of the patellofemoral joint, frequently affected by OA.[1,5] However, they did not study simultaneous activity, strengthening, and coordination of other predominant lower knee muscle groups like the tibias anterior, hamstring, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius muscles, etc., to further prevent or reduce OA affect. Continuous studies should be completed because it is well known that all muscles groups work in close coordination and synchrony wherein the activity of one muscle group affects that of other.[40,41]

Another area of interest may be to understand the neuromuscular efficiency during the performance of routine tasks. It is calculated as the ability of an individual to generate force (or force moment) for the same level of muscle activation.[42,43] It refers to the method by which muscles strengthen due to changes at the neuromuscular junction. In other words, the muscle strengthens because the connection between the brain and the muscle improves. As neuromuscular efficiency improves, muscle strength goes up. In fact, much of the initial strength gained during any rehabilitation program is due to neuromuscular efficiency and not increased muscle mass. Hip abductor activity has been studied in sagittal plane for step-up and step-down tasks. No significant differences have been seen and it would be worthwhile to study activity in lateral (frontal) plane. Also, useful information in determining walking pattern symmetry (speed and acceleration) between the limbs in healthy individuals without OA in their muscle activity patterns and during task modulation has been obtained.[19] There are only few electromyogram (EMG) gait studies for those with knee OA, examining various degrees of moderate OA with no studies on those with severe OA.[3,17,44] An EMG-driven modeling approach has not been used to estimate articular loading in people with knee OA.[45,46] From the above, an attempt will be made sooner or later on developing an EMG-based model for estimating articular loading in people with knee OA. This would help in determination of articular loading based on EMG patterns examined from the muscles working in synchrony around the knee joint.

Also, various supplementary forms of rehabilitation have been prescribed which include different physical agents. These devices use physical modalities to produce useful therapeutic effects. Heat, cold, pressure, light, and even electricity have been used for thousands of years to accelerate healing and decrease pain.[47] Heat agents can come in two forms, such as heat packs that relax the muscles and also devices such as ultrasound (US) that may produce temperature elevations of 4°C–5°C at depths of 8 cm.[40] Ultrasound (US) has been used for decades as a therapy for musculoskeletal disorders such as tendinitis, tenosynovitis, epicondylitis, bursitis, and OA. US converts electrical energy into an acoustic waveform, which is then changed into heat as it goes through tissues of varying resistances.[48] There are two different ways in which US can be used to treat disease, continuous and pulsed US. Continuous US are typically responsible for the heating effect in the tissues because it uses an unmodulated continuous-wave US beam with intensities limited to 0.5-2.5 W/cm2. In comparison, the pulsed US beam is modulated to deliver brief pulses of high intensity separated by longer pauses of no power. It is suggested that pulsed US be recommended for acute pain and inflammation and continuous US for the treatment of restricted movement.[40,48] It was discovered that therapeutic US frequently used in physiotherapies was more effective than the control treatment, and none of them was found to be superior to any other.[47] The effectiveness of US was also shown by Mao-Hsiung Huang et al., who stated that US treatment could increase the effectiveness of isokinetic exercise for functional improvement of knee OA, and pulsed US had a greater effect than continuous US.[49]

While US employs heat to treat OA, electrical stimulation, as the name implies, uses electricity. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is one of the most widely used physical modalities for the management of OA knee. TENS research has been conducted for the past 20 years, yet the best stimulation frequency of TENS in the management of knee OA pain is still under study. Many studies have already been completed and demonstrated no significant differences in immediate pain relief between the groups.[38,42] Varying frequencies of electrical stimulation and pulse quantity have been used with no significant results as stated. But low-and high-frequency stimulations of TENS seem to work on the various analgesic mechanisms to different extent. Therefore, some researchers advocate that alternating stimulations of TENS will produce analgesic effects.[50] Some researchers were determined to find the optimal stimulation frequency and they revealed that the repeated applications of active TENS (10 sessions study) led to a significant reduction in subjective pain sensation. Regrettably, they determined that the differences between the varying sets of frequencies had no changes. Therefore, it shows that TENS does work but the optimal frequency and pulse has yet to be determined.[44]

Pharmacological treatment modalities

Reducing knee OA severity on the WOMAC scale may further include pharmacological methods. Acetaminophen, aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used as pain relief medicines to treat OA. Excessive use of NSAIDs can lead to gastric complications, ulcers, increased risk for hospitalization, adverse side effects, and death.[12,48] Glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate are two nutritional supplements that have been reported to “cure” arthritis. As glucosamine and chondroitin are produced within the body and are used in the manufacture or repair of cartilage, it is suggested that the synthetic versions work the same way.[48] Numerous pharmaceuticals have been proposed, but as no therapy has shown ideal results, it is important to evaluate the risk/benefit ratio before the same is prescribed by the physician for use.[11] These results led to studies to determine other non-pharmacological treatments such as acupuncture. This has been done with standardized minimal-depth acupuncture at non-acupuncture points (sham acupuncture), applied in addition to physiotherapy and as-needed anti-inflammatory drugs. The study showed that compared with physiotherapy and as-needed anti-inflammatory drugs, addition of either Traditional Chinese Acupuncture (TCA) or sham acupuncture led to greater improvement in WOMAC score at 26 weeks, although there were no significant differences between TCA and sham.[51] Intra-articular hyaluronic acid has a long history of injections into the joints of arthritic animals to improve their performance (therapy is called as “viscosupplementation”). Hyaluronic acid is the lubricating substance within the joint which may be lost during osteoarthritis.[32] It has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a device for the treatment of OA in humans since 1997. Although thought to have worked with arthritis, it was found that intra-articular hyaluronic acid, at best, has a small effect in the treatment of knee OA compared with an intra-articular placebo.[39]

The most drastic treatment to knee OA is partial or total knee replacement. In the recent years, this invasive surgery has become less critical with smaller incisions and less time spent in the hospital. Generally with a knee replacement, a metal cap is fitted on to the bottom of the thigh bone (femur) and a plate is fitted on top of the shin bone (tibia). The joint between the two is a plastic hinge joint. The plastic joint is used to make the connection of the plate sturdy on the tibia. In newer designs, it can slide and twist, adding the ability of a natural movement. It is most common for arthritis problems to affect the medial (inside) aspect of the knee; therefore, partial knee replacements can be done and only the inner portion of the knee joint is replaced. When replacing the medial knee, more range of motion is expected.[38,42] Currently, there are no strong indicators in place to assess the criteria to be employed to identify the potential candidates for total knee arthroplasty (TKA); nor is there professional consensus around such indications. However critical the surgery may seem, it has been shown that both TKA and total knee arthroplasty revision (TKAR) are associated with improved function. The evidence is clear when follow-up period of up to 2 years indicates positive results including studies that extend to 5 and even 10 years of follow-up.[50] The recovery is even better and faster if combined with appropriate PT programs under the supervision of qualified medical practitioners.

Discussion and Conclusion

As discussed in the paper, the pharmacological treatment methods are quite often utilized for achieving better results for patients with knee OA, along with a non-pharmacological exercise and modalities treatment regimen.[9,10,12] Despite the available treatment methods, there still persist a host of inadequacies that make cost containment a real issue.[15] It may be stated that inadequate diagnostic procedures, referrals, and treatment modalities which lack evidence for efficacy (e.g., massage, traction, and stretching) are still currently being utilized in approximately half of all OA patients receiving physiotherapy.[15] This poses a great healthcare issue for those suffering with OA-related problems, as sufficient and reliable treatment protocols do not exist currently. The future demands for healthcare are enormously outpacing the current methods of approach as can be seen here with just one disease. Hence, higher standards of quality research are going to be crucial in future in defining the diagnostic procedures, assessments, treatment modalities, and evaluations needed for a more cost-effective and treatment-effective program of tomorrow.

Future Course

It has not been proven that exercise programs aiming to improve maximum concentric and eccentric strength of the above lower limb muscles lead to a lower knee muscle coordination, which may be more beneficial in improving functional ability in OA patients.[52] The study and research in the field of biomechanical patterns for knee OA subjects is innovative and beneficial because till now not much literature reports are available to determine the role of different lower extremity muscle groups, testing for neuromuscular efficiency, biomechanical changes during gait, and their correlation with each other with regards to the onset and development of knee OA condition.[2,5,6] The biomechanical and neuromuscular factors should be studied simultaneously in larger, longitudinal studies with consideration of multidimensional combination of the above-mentioned knee OA risk factors presented by an individual.[18] Due to the fact that OA is affecting millions worldwide, measures need to be developed to prevent early progression of the disease. The interest in understanding the biomechanical changes presented by patients with knee OA would be important for a better comprehension of the development of the disease and to establish a therapeutic approach appropriate to each stage of the disease.[18] The discovery of appropriate changes in the biomechanical patterns of lower limb joints will lead to advanced physical rehabilitation protocols including treating with US, TENS, and additional PT strategies, and comparing them to know which one of these may help in minimum progression of the disease leading to delay in need for total knee replacement surgery and thereby improving the quality of life by providing mobility and relief to huge population affected by OA.[53,54]

Bibliographic Notes

Dr. Dinesh Bhatia pursued his PhD in Biomechanics and Rehabilitation Engineering from Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology (MNNIT), Allahabad (Uttar Pradesh), India. He is employed as an Assistant Professor (Sr. Grade) at the Biomedical Engineering Department, Deenbandhu Chhotu Ram University of Science and Technology, Murthal (Sonepat), Haryana, India since 2006. He was sponsored by the Indian National Academy of Engineering (INAE) fellowship to work at the Centre for Biomedical Engineering, IIT and AIIMS, New Delhi, from May to July 2011. He was selected for the “young scientist award” by the Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Govt. of India in 2011 to pursue further research at the Adaptive Neural Systems Laboratory, Florida International University, Maimi, Florida, USA from 2011-12. He has research papers in various referred international and national journals with teaching and research experience of more than nine years. He is working on funded projects from Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India, on physically challenged and paralyzed people. His research focuses on understanding muscle mechanics, joint kinematics and dynamics involved in performing locomotion and routine tasks and undermining it effects during an injury or disease.

Tatiana Bejarano is a graduate student at the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA. She has participated in research internships at Northwestern University dealing with Bioengineering Education Research, and Carnegie Mellon University where she did research on Computational Neuroscience and how people perceive images using FMRI data. Currently she is working in the Adaptive Neural Systems Laboratory of the department, performing research on understanding the biomechanical parameters associated with knee osteoarthritis. In the future, she plans to attend Medical school where she can continue to perform further research in the field and apply these techniques in her practice.

Mario Novo is a Graduate Assistant pursuing his DPT at Department of Physical Therapy, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA. His research interests lies in understanding human body movement and kinematics. He is technically well equipped working on studying human gait, electromyogram (EMG), and motion capture for data acquisition and analysis.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Dinesh Bhatia has been awarded “Young Scientist” award (Boyscast fellowship 2010-2011), funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, for carrying out research work in knee biomechanics at Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA.

Footnotes

Source of Support: SR/BY/E-14/10, Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Hinman RS, Hunt MA, Creaby MW, Wrigley T, McManus FJ, Bennell KL. Hip muscle weakness in individuals with medial knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1190–3. doi: 10.1002/acr.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiden T, Lloyd D, Ackland T. Knee extension and flexion weakness in people with knee osteoarthritis: Is antagonist contraction a factor? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39:807–15. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Childs JD, Sparto PJ, Fitzgerald GK, Bizzini M, Irrgang JJ. Alterations in lower extremity movement and muscle activation patterns in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2004;19:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Likivainio T, Arokoski J. Physical function and properties of quadriceps femoris muscle in men with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:2185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Likivainio T, Bragge T, Hakkarainen M, Karjalainen PA, Arokoski J. Gait and muscle activation changes in men with knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2010;17:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinman RS, Bennel K, Metcalf B, Crossley K. Delayed onset of quadriceps activity and altered knee joint kinematics during stair stepping in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1080–6. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain S. Arthritis: Freedom from pain. [Last accessed on Dec 2011]. Available from: http://www.completewellbeing.com/article/towards.a.joint.effort/, 2008 .

- 8.Ringdahl E, Pandit S. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:1287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magrans-Courtney T, Wilborn C, Rasmussen C, Ferreira M, Greenwood L, Campbell B, et al. Effects of diet type and supplementation of glucosamine, chondroitin, and MSM on body composition, functional status, and markers of health in women with knee osteoarthritis initiating a resistance-based exercise and weight loss program. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2011;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esser S, Bailey A. Effects of exercise and physical activity on knee OA. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:423–30. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0225-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salve H, Gupta V, Palanivel C, Yadav K, Singh B. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis amongst perimenopausal women in an urban resettlement colony in south Delhi. Indian J Public Health. 2010;54:155–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.75739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kon E, Filardo G, Drobnic M, Madry H, Jelic M, Dijk N, et al. Non-surgical management of early knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:436–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1713-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carvalho NA, Bittar ST, Pinto FR, Ferreira M, Sitta RR. Manual for guided home exercises for osteoarthritis of the knee. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2010;65:775–80. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322010000800007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voelker R. Few adults with knee osteoarthritis meet national guidelines for physical activity. JAMA. 2011;306:1428–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smink AJ, van den Ende CH, Vliet Vlieland TP. Beating osteoarthritis: Development of a stepped care strategy to optimize utilization and timing of non-surgical treatment modalities for patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1623–9. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1835-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai Y, Chang H, Sinacore J, Lewis J. Alteration in multijoint dynamics in patients with bilateral knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1297–304. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubley-Kozey C, Deluzio K, Dunbar M. Muscle co-activation patterns during walking in those with severe knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2008;23:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson JL, Deluzio KJ, Dunbar MJ, Caldwell GE, Hubley-Kozey CL. The association between knee joint biomechanics and neuromuscular control and moderate knee osteoarthritis radiographic and pain severity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessi GC, Silva PR, Gimenez A, Say K, Oliveira A, Mattiello S. Male subjects with early stage knee osteoarthritis do not present biomechanical alterations in the saggital plane during stair descent. Knee. 2012;19:387–91. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogind H, Bibow-Nielsen B, Jensen B, Moller HC, Frimodt-Moller H, Bliddal H. The effects of a physical training program on patients with osteoarthritis of the knees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1421–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escalante Y, Saavedra JM, Garcia-Hermoso A, Silva AJ, Barbosa TM. Physical exercise and reduction of pain in adults with lower limb osteoarthritis: A systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 1998;23:175–86. doi: 10.3233/BMR-2010-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang MH, Chen CH, Chen TW, Weng MC, Wang WT, Wang YL. The effects of weight reduction on the rehabilitation of patients with knee osteoarthritis and obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:398–405. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)13:6<398::aid-art10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel R, Ryder M, Garber M, Allison S. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:173–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross W. Adey biological effects of electromagnetic fields. J Cell Biochem. 1993;51:410–6. doi: 10.1002/jcb.2400510405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ciombor DM, Aaron RK, Wang S, Simon B. Modification of osteoarthritis by pulsed electromagnetic field: A morphological study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:455–62. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fini M, Giavaresi G, Carpi A, Nicolini A, Setti S, Giardino R. Effects of pulsed electromagnetic fields on articular hyaline cartilage: Review of experimental and clinical studies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59:388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puett DW, Griffin MR. Published trials of non-medicinal and noninvasive therapies for hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:133–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-2-199407150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sen A, Gocen Z, Unver B, Karatosun V, Gunal I. The frequency of visits by the physiotherapist of patients receiving home-based exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2004;11:151–3. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deyle GD, Allison SC, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Stang JM, Gohdes DD, et al. Physical therapy treatment effectiveness for osteoarthritis of the knee: A randomized comparison of supervised clinical exercise and manual therapy procedures versus a home exercise program. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1301–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McQuade KJ, de Oliveira AS. Effects of progressive resistance strength training on knee biomechanics during single leg step-up in persons with mild knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2011;26:741–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, Kupelnick B, Scott T, Schmid CH. Tai chi on psychological well-being: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;10:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong C. Osteoarthritis pain relief remedies. [Last accessed on 2007 Jul]. Available from: http://www.altmedicine.about.com/od/healthconditionsdisease/a/osteoarthritis.htm .

- 33.Hernandez V. Wellness as a whole. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec]. Available from: http://www.bodycareschoolofthehealingarts.com/

- 34.Lund H, Weile U, Christensen R, Rostock B, Downey A, Bartels E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of aquatic and land-based exercise in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:137–44. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fransen M, Nairn L, Winstanley J, Lam P, Edmonds J. Physical activity for osteoarthritis management: A randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating hydrotherapy or tai chi classes. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;57:407–14. doi: 10.1002/art.22621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evcik D, Sonel B. Effectiveness of a home-based exercise therapy and walking program on osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22:103–6. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrella RJ, Bartha C. Home based exercise therapy for older patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2215–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sled EA, Khoja L, Deluzio KJ, Olney SJ, Culham EG. Effect of a home program of hip abductor exercises on knee joint loading, strength, function, and pain in people with knee osteoarthritis: A clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2010;90:895–904. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson D. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2003;290:3115–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.23.3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhatia D, Bansal G, Joshi D, Anand S, Tewari RP. Coordination between lower limb muscles in different locomotion activities. Int J Biomed Eng Technol. 2011;6:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Luca CJ. The use of surface electromyography in biomechanics. J Appl Biomech. 1997;13:135–63. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glazier RH, Dalby DM, Badley EM, Hawker GA, Bell MJ, Buchbinder R, et al. Management of common musculoskeletal problems: A survey of ontario primary care physicians. CMAJ. 1998;158:1037–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tesch PA, Dudley GA, Duvoisin MR, Hather BM, Harris RT. Force and EMG signal patterns during the repeated bouts of concentric or eccentric muscle actions. Acta Physiol Scand. 1990;138:263–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1990.tb08846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Law PP, Cheing GL. Optimal stimulation frequency of transcutaneus electrical nerve stimulation on people with knee osteoarthritis. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:220–5. doi: 10.1080/16501970410029834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar D, Rudolph K, Manal K. EMG driven modeling approach to muscle force and joint load estimations: Case study in knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:377–83. doi: 10.1002/jor.21544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chau T. A review of analytical techniques for gait data. Part 1: Fuzzy, statistical and fractal methods. Gait Posture. 2001;13:49–66. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(00)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kozanoglu E, Basaran S, Guzel R, Uysal F. Short term efficacy of ibuprofen phonophoresis versus continuous ultrasound therapy in knee osteoarthritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:333–8. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinals RS. Pharmacologic treatment of osteoarthritis. Clin Ther. 1992;14:336–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang MH, Lin YS, Lee CL, Yang RC. Use of ultrasound to increase effectiveness of isokinetic exercise for knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1545–51. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kane RL, Saleh KJ, Wilt TJ, Bershadsky B. The functional outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1719–24. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, Witte S, Kramer J, Maier C, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: A three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:12–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patsika G, Kellis E, Amirdis IG. Neuromuscular efficiency during sit to stand movement in women with knee osteoarthritis. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2011;21:689–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klaiman MD, Shrader JA, Danoff JV, Hicks JE, Pesce WJ, Ferland J. Phonophoresis versus ultrasound in the treatment of common musculoskeletal conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1349–55. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fitzgerald GK, Childs JD, Ridge TM, Irrgang JJ. Agility and perturbation training for a physically active individual with knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2002;82:372–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]