Abstract

One of the greatest challenges in cancer therapy is to develop methods to deliver chemotherapy agents to tumor cells while reducing systemic toxicity to non-cancerous cells. A promising approach to localizing drug release is to employ drug-loaded nanoparticles with coatings that release the drugs only in the presence of specific triggers found in the target cells such as pH, enzymes, or light. However, many parameters affect the nanoparticle distribution and drug release rate and it is difficult to quantify drug release in situ. In this work, we show proof of principle for a “smart” radioluminescent nanocapsule with X-ray excited optical luminescence (XEOL) spectrum that changes during release of the optically absorbing chemotherapy drug, doxorubicin. XEOL provides an almost background-free luminescent signal for measuring drug release from particles irradiated by a narrow X-ray beam. We study in vitro pH triggered release rates of doxorubicin from nanocapsules coated with a pH responsive polyelectrolyte multilayer using HPLC and XEOL spectroscopy. The doxorubicin was loaded to over 5 % by weight, and released from the capsule with a time constant in vitro of ~ 36 days at pH 7.4, and 21.4 hr at pH 5.0, respectively. The Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules are also paramagnetic at room temperature with similar magnetic susceptibility and similarly good MRI T2 relaxivities to Gd2O3, but the sulfur increases the radioluminescence intensity and shifts the spectrum. Empty nanocapsules did not affect cell viability up to concentrations of at least 250 μ/ml. These empty nanocapsules accumulated in a mouse liver and spleen following tail vein injection, and could be observed in vivo using XEOL. The particles are synthesized with a versatile template synthesis technique which allows for control of particle size and shape. The XEOL analysis technique opens the door to non-invasive quantification of drug release as a function of nanoparticle size, shape, surface chemistry and tissue type.

Keywords: pH triggered drug release, release monitoring, radioluminescent nanocapsules, theranostics

Nanoparticle drug carriers with stimuli-responsive controlled drug release have the potential for site selective controlled release. The stimuli such as pH,1-4. temperature,5-6. redox reactions,7-8. enzyme,9-11. and light12-14. have been studied as triggers for drug release. The in vivo drug release rate and location depends upon many factors including nanoparticle size, shape, composition, and surface chemistry as well as physiological factors such as vasculature and blood flow rate, pH, and enzyme concentration. In principle one would like to optimize the nanoparticle parameters in order to maximize drug release into tumors and minimize systemic release in the blood, however, it is a challenge to measure release in vivo after systemic administration. To rationally design effective chemotherapy carriers, there is a critical need to develop flexible theranostic nanocarriers that can be localized in tissues to monitor drug release at high resolution. While positron emission tomography (PET)15-17. and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)18. are the most common molecular in vivo imaging techniques, there is no way to distinguish encapsulated from released drug.

Doxorubicin (DOX) is a chemotherapy drug used to treat a wide range of cancers. However, its serious adverse effects such as suppression of hemaropoiesis, gastrointestinal and cardiac toxicity limit its applications.19-20. It is crucial to control the concentration of doxorubicin specifically in the blood circulation, normal tissues, and tumor tissues. Unfortunately, DOX clears rapidly from circulation (circulation half life of < 5 min)21. which makes it difficult to specifically target tumor cells using free drug. A pH-responsive controlled release system for DOX could address this issue by releasing drugs into the blood only gradually, but rapidly release drugs after endocytosis in acidic tumor lysosomes and endosomes. The particles could be targeted to tumors via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect and by functionalizing the nanoparticle surface with appropriate antibodies or other targeting molecules. For example, in 2005, Lee et al. reported pH-sensitive micelles as carriers for DOX to enhanced tumor specificity and endosome disruption property on the carrier.22-23. Recently, mesoporous silica has also gained attention as drug storage and release hosts due to their mesoporous structure, high surface area, and easily modified surface.24-27. Zhu and co-workers reported pH-controlled delivery of DOX to cancer cells based on small mesoporous carbon nanospheres. However, these studies did not use radioluminescent nanoparticles or provide a method to quantify the release rate in situ.

Recently, Xing group developed X-ray luminescence computed tomography (XLCT) to image the location of radioluminescent particles embedded in tissue using a narrow X-ray beam (e.g. 1 mm) to irradiate the particles and a photodetector to collect the luminescence.28-32. The X-ray excited optical luminescence is only generated in the path of the narrow X-ray beam which penetrates deeply through tissue and maintains focus through several centimeters. The spatial resolution is determined by the narrow X-ray beam width. The image is formed point-by-point by measuring the total luminescent intensity collected at each X-ray beam position while the beam is scanned across the sample. A three-dimensional image is generated by rotating the sample relative to the X-ray beam and using tomographic reconstruction algorithms. XLCT is a low background technique because only the radioluminescent particles emit light during imaging process. Xing group also developed a limited-angle X-ray luminescence tomography (XLT) to more rapidly acquire images without rotating the X-ray relative to the sample, but with worse resolution along one of the three dimensions.33. Based on their simulation, this technique allows imaging μ/ml particle concentrations through 5 cm of tissue with ~ 10 mGy dose of X-ray. This technique is expected to be especially useful in surgical applications because of its short acquisition time, high depth resolution, and low X-ray dose.

In our previous work, we extended these XEOL approaches to perform high spatial resolution chemical analysis in tissue by using the radioluminescent particles as an in situ localized light source for spectrochemical analysis in conjunction with nearby chemical indicator dyes. For example, to measure pH on an implanted surface, we placed pH paper upon a radioluminescent film with embedded Gd2O2S:Tb particles to alter the their spectral ratio of radioluminesence peaks in a pH dependent manner.34. We also demonstrated submilimeter imaging through a 1 cm of chicken breast.34-35. In addition to pH indicators, the principle applies to other materials that absorb light, including silver and gold nanoparticles deposited on films.36. We also found that the XEOL spectrum of hollow Gd2O3:Eu nanoparticles is greatly reduced by the presence of an iron oxide core.37. Based upon these results, we hypothesized that we could use radioluminescence to monitor the release of dyes and optically absorbing drugs from the core of radioluminescent nanocapsules.

In this work, we synthesize rare-earth (Tb, Eu) doped Gd2O2S based radioluminescent capsules as a drug nanocarrier and drug release monitor. Compared with gadolinium oxide doped with Eu, Tb and Eu doped gadolinium oxysulfide possesses higher photo conversion efficiency (approximately 60,000 visible photons/MeV for Gd2O2S:Tb, and Gd2O2S:Eu, 40,000 visible photons/MeV for Gd2O3:Eu) ).35. Their bright radioluminescence (see supporting information Fig. S1) can be used to track the delivered drug and monitor the drug release process. Meanwhile, these capsules serve as good T2-weighted MRI contrast agent which can be used as a complementary imaging mode for X-ray functional imaging.35.

Results and discussion

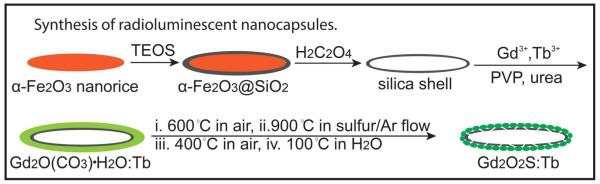

Particle shape plays a crucial role in the application of drug delivery systems.38-39. Some previous studies on particles with high aspect ratio (e.g. nanorod, nanorice) showed that those particles (> 500 nm in length) with high aspect ratio have a slower clearance rate than particles with low aspect ratio (e.g. spherical particles) in the application of drug delivery systems.40,41. We chose ellipsoidal hollow silica nanorice as templates to synthesize monodispersed ellipsoidal nanocapsules. The technique is highly flexible for controlling the nanocapsule size and shape: by varying the synthesis condition of template,42-44. the length of these nanocapsules can be tuned from 20 nm to 600 nm and the aspect ratio can be adjusted from spheres to prolate spheroids. In order to obtain monodispersed silica nanoshells, as shown in Fig. 1, monodispersed hematite nanorice is first prepared, then treated through a modified Stöber procedure to form a thin silica shell. Finally the hematite core was removed by etching in 0.5 M oxalic acid for 17 h. The monodispersed silica shell were then coated with a layer of Gd2O(CO3)2•H2O doped with terbium (Tb3+/Gd3+= 2.4% mol) or europium (Eu3+/Gd3+=5.1% mol) through a homogeneous precipitation method from gadolinium, europium nitrate. After heat treatment at 600 °C for 1 h, the amorphous Gd2O(CO3)2•H2O layer transformed into Gd2O3. The above product was treated by sulphur gas with argon flow at 900 °C for 1h to convert the Gd2O3 to Gd2O2S. The obtained nanoparticles was re-heated at 400 °C in the air for 1h and incubated in boiling water for 2 h to remove the residue of sulphur and gadolinium sulphide.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of radioluminescent nanocapsules.

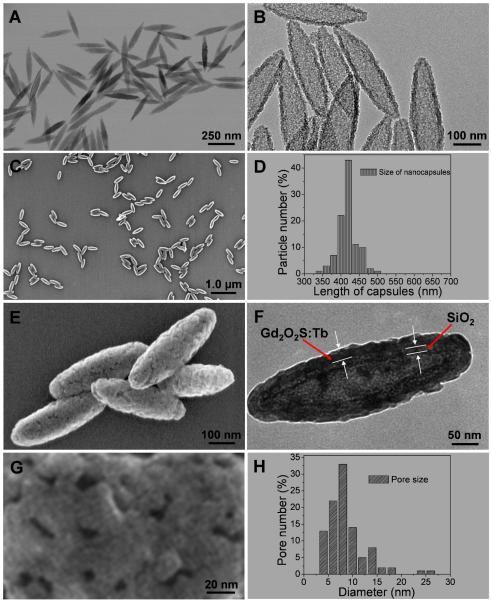

TEM images in Fig. 2A show monodispersed spindle shaped iron oxide seeds. Fig. 2B represents the intact silica shell after the iron oxide core was removed by dissolving in oxalic acid. The SEM image in Fig. 2C and narrow size distribution in Fig. 2D indicate the monondispersed nanocapsules were obtained successfully with an average length of 420 +/−20 nm and width of 130 nm +/−15 nm. The nanocapsules possess a 10 nm thick inner silica shell and a 25 nm thick outer Gd2O2S:Tb radioluminescent shell (Fig. 2F) with porous morphology (Fig. 2E, Fig. 2G, Figure S2, Supporting information). The pores are irregular in shape, with an average diameter of (8.5 +/− 2 nm). These visible pores in the shell (Gd2O2S:Tb) of the nanocapsules likely facilitate drug loading and releasing. Crystal structure and composition of these nanocapsules were characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and the host is shown as hexagonal phase of Gd2O2S according to the data of JCPDS card no. 26-1422 (Supporting information, Fig. S3). Gd2O2S:Eu with similar aspect ratio were also synthesized by the same silica nanotemplate (Supporting information, Fig. S4 and Fig. S5). The tunable size range and the morphology make these nanocapsules promising as drug carriers. In order to apply these nanocapsules in biological applications, the stability of the nanocapsules was tested in 0.3 % (v%) acetic acid (pH ~3.0). The SEM images in Fig. S6 show no discernible dissolution indicating that the nanocapsules are very stable under pH 3 at 37 °C even after 24 hr. The cell viability of our X-ray phosphors on MCF-7 breast cancer cells is also tested and it’s shown that cell viability is greater than 90% when the concentration of Gd2O2S:Tb and Gd2O2S:Eu is as high as 250 μg/ml, after incubation for 24 h (Supporting information, Fig. S7).

Fig. 2.

(A) TEM image of monodispersed iron oxide seeds, (B) TEM image of hollow silica shell after removing iron oxide core, (C) SEM image of monodispersed radioluminescent nanocapsule (Gd2O2S:Tb (Tb/Gd=2.4% mol), (D) Size distribution of the nanocapsules, (E) High magnification SEM image of nanocapsule, (F) TEM image of the nanocapsule, (G) High magnification SEM image of surface of a nanocapsule, (H) pore size distribution from 100 nanocapsules with 3786 pores, the diameter of each pore is calculated by the average value of the maximum and minimum length of the pore.

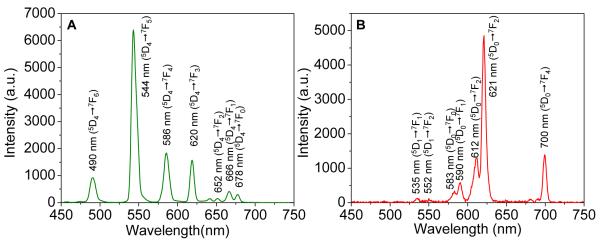

The radioluminescence spectra of nanocapsules (Gd2O2S:Tb, Eu) are presented in Fig. 3. The radioluminescence mechanism involves the generation of electron-hole pairs in the host lattice following X-ray absorption. These electron-hole pairs then excite Tb3+ and Eu3+ centers which emit visible and near infrared light. The conversion efficiency is 60,000-70,000 visible photons/MeV X-ray photon in bulk Gd2O2S:Eu, corresponding to an energy efficiency of approximately 15%.45-47. The narrow luminescent peaks of Gd2O2S:Tb are attributed to the transitions from the 5D4 excited-state to the 7FJ (J=6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0) ground states of the Tb3+ ion. The 5D4 → 7F5 transition at 544 nm is the most prominent group. The 5D0,1 →7FJ (J=0, 1, 2, 4) transition lines of the Eu3+ ions generate the intense peak at 590, 612, 620, 720 nm. The strongest red emission which splits into two peaks at 621 and 612 nm arises from the forced electric-dipole 5D0→7F2 transitions of the Eu3+ ions. These nanocapsules displayed similar fluorescence spectra under blue excitation light (460-495 nm) (Supporting information, Fig. S8). However, blue light does not penetrate as deeply into tissue as X-rays, and unlike X-rays, does not stay collimated or focused which dramatically reduces image resolution.

Fig. 3.

X-ray excited optical luminescence spectra of empty nanocapsules. (A) Gd2O2S:Tb, (B) Gd2O2S:Eu.

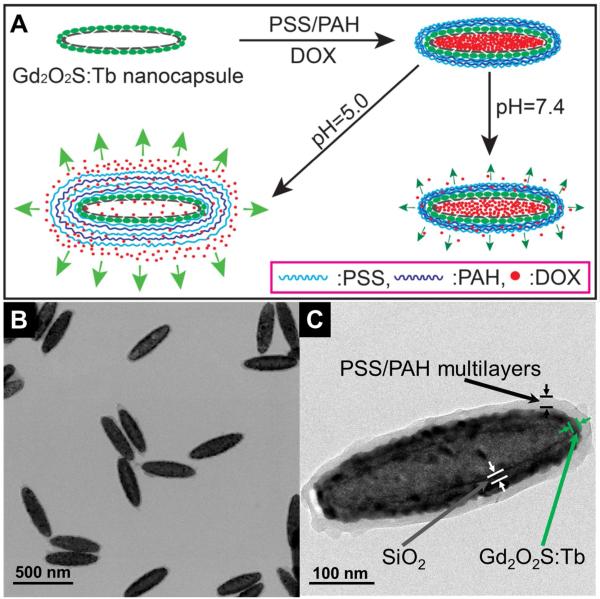

Styrenesulfonate sodium (PSS) and poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) are widely used polyelectrolytes in pH-controlled release systems.1-4. In order to create a stimuli-responsive system for DOX, our X-ray luminescent nanocapsules coated with eight layers of negative charged PSS and seven layers of positive charged PAH to encapsulate DOX with layer by layer assembly (Fig. 4, the particle is denoted as DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH). Due to the surface of our nanocapsules are positive charged (+14.9 mV, Fig. S9, supporting information), the first layer of polyelectrolyte coated on nanocapsules is PSS. After the layer by layer coating, the nanocapsules are coated by an average of 30 nm thick polyelectrolyte with a layer of PSS on the surface. Cell viability test indicates that the empty Gd2O2S:Tb nanocapsules coated with PSS/PAH multilayers show no significant toxicity to a concentration of at least 250 μg/ml, the highest concentration measured (Supporting information, Fig. S7). In order to demonstrate that the DOX is loaded into the nanocapsules, nanocapsules filled with solid core were synthesized as a control by using the silica coated hematite instead of hollow silica shells as the template. The same DOX loading and polyelectrolyte coating were employed to the nanocapsules with a solid core (iron sulfide). From the released DOX from these solid particles, we calculate that the hollow particles release approximately 20× more DOX than the solid-core particles, indicating that most of the DOX is stored in the core of the hollow particles (Supporting information, Fig. S10)

Fig. 4.

(A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH and pH-responsive release of DOX. (B) TEM image of DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH nanocapsules. (C) High resolution TEM image of a single DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH nanocapsule.

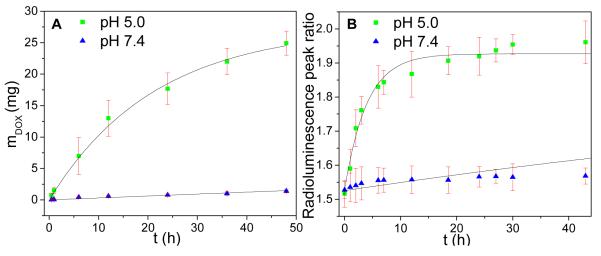

To study the release rate at normal physiological pH and in acidic cancer environments, we measured the release rate in pH 7.4 PBS and 5.0, respectively. The cumulative release profile of doxorubicin from these nanocapsules is pH dependent (Fig. 5). The drug release is enhanced at pH 5.0 which is applicable for cancer therapy due to the low pH environment in tumors and within endosomes after internalization by cancer cells.48-49. Based upon exponential fitting to the HPLC release curve, the release rate time constant was estimated to be ~ 36 days at pH 7.4, and 21 hr at pH 5.0. From the released DOX at pH 5.0 after 48 h, the encapsulated DOX in DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH was over 5% by weight.

Fig. 5.

(A) Cumulative release of doxorubicin from DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH at pH 5.0 and 7.4, measured with HPLC. The line fits data to a single exponential curve with a saturation of 27.4 mg. This saturation is calculated based on the fit at pH 5.0. (B) Peak ratio of real time radioluminescence intensity at 544 and 620 nm as a function time in pH 5.0 and pH 7.4 buffers. The line fits data to a single exponential curve with a saturation of 1.93. This saturation is calculated based on the fit at pH 5.0.

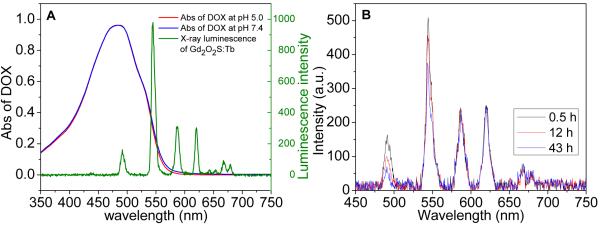

Our pH-responsive controlled release system is also able to monitor the release process of DOX at different pH by detecting the radioluminescence of Gd2O2S:Tb nanocapsules (Fig. 6). At pH 5.0 and 7.4, DOX has a similar broad absorption of light from 350 to 600 nm which overlaps with some of the XEOL peaks of Gd2O2S:Tb (Fig. 6A). Fig. 6B shows the intensity ratio of X-ray luminescence at 544 nm and 620 nm increases with the release of doxorubicin because local luminescence absorption by DOX decreases when DOX is released. We observed the similar luminescent increase of nanoparticle with iron oxide as a core when the iron oxide are partially dissolved.37. The mechanism is likely a combination of near field absorption and/or energy transfer. Future work will elucidate the mechanism by measuring the XEOL spectra and lifetime. The peak intensity ratio reaches a maximum value when the DOX concentration in the particles is in equilibrium with the solution concentration.

Fig. 6.

(A) Absorption spectra of DOX (0.05 mg/ml at pH 5.0 and 7.4) and radioluminescence spectrum of Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH, (B) Radioluminescent spectra of DOX@Gd2O2S:Tb@PSS/PAH at pH 5.0 taken at three different times during drug release.

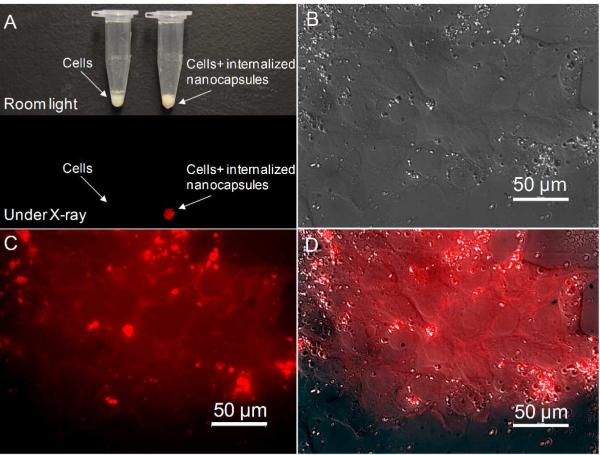

In order to examine the uptake of these nanocapsules by cancer cells, nanocapsules doped with europium (Gd2O2S:Eu) were incubated with MCF-7 cancer cell and washed multiple times to eliminate nanocapsules from the cell culture media. The internalized nanocapsules were brightly luminescent under X-ray radiation (Fig. 7A). The bright fluorescence signal of nanocapsules is very useful in drug localization and cell labeling. Fig. 7C shows the fluorescence signal of the Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules in MCF 7 cancer cell after multiple washing step to eliminate nanocapsules from the cell culture media.

Fig. 7.

(A) Photograph of MCF-7 breast cancer cells with and without internalized nanocapsules (Gd2O2S:Eu) viewed under room light and X-ray irradiation. (B)Transmitted light differential interference contrast microscopy image of MCF-7 cells with internalized nanocapsules (Gd2O2S:Eu). Fluorescence microscopy image of the cells shown in (B). (D) Merged image of (B) and (C).

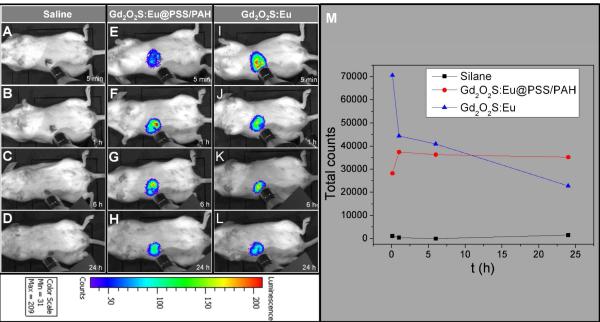

To demonstrate that the nanoparticle XEOL can be imaged in vivo using a IVIS Lumina-XR Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, US) during irradiation with miniature X-ray source (Amptek Mini X-ray tube, Ag target, Amptek Inc. MA, USA), 200 μL of 1 mg/mL Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules coated with PSS/PAH multilayers were inject into a mouse tail vein. The effective nanocapsule concentration in the mouse is about 133 μg/ml (the blood volume of a mouse is around 1.5 ml) which did not affect cell viability for MCF7 breast cancer cells in vitro. Furthermore, a preliminary Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) study was carried out and it shows no morbidity or weight loss was observed for doses up to 400 mg/kg. The in vivo accumulation of the nanocapsules in the liver was evident under X-ray irradiation with 0.1 s exposure time. Compared to the Gd2O2S:Eu without PSS/PAH mutilayers (Fig. 8), the accumulation rate for polyelectrolytes coated nanocapsules is slower in the first 1 h. Post mortem, XEOL images of the excised organs confirmed that the nanocapsules accumulated in liver and spleen (Supporting information, Fig. S11).

Fig. 8.

Representative luminescent images of accumulation of Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules with and without polymer coating in mouse. (A) 5 min, (B) 1 h, (C) 6 h, (D) 24 h after the mouse was injected with saline (200 μl). (E) 5 min, (F) 1 h, (G) 6 h, (H) 24 h after the mouse was injected with Gd2O2S:Eu@PAH/PSS nanocapsules (200 μl, 1 mg/ml). (I) 5 min, (J) 1 h, (K) 6 h, (L) 24 h after the mouse was injected with Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules (200 μl, 1 mg/ml). (M) Total radioluminescent intensity counts as a function of time after injection.

Recent studies describe the synthesis and applications of gadolinium oxide (Gd2O3) nanoparticles as MRI contrast agents.37, 50-54. However, to our knowledge, no investigation of gadolinium oxysulfide based MRI contrast agents are reported so far. Our luminescent nanocapsules mainly consisting of gadolinium oxysulfide (Gd2O2S) also have similar magnetic properties to gadolinium oxide which make them a potential MRI contrast agent.37. Room temperature magnetic hysteresis loops of the nanocapsules (Gd2O2S:Tb, Gd2O2S:Eu) are shown in Fig. S12. Both types of nanocapsules are paramagnetic as evident by the linear relation between the particle magnetization and the applied magnetic field with no indication of saturation up to applied fields of at least 30 kOe. Both Gd2O2S:Tb and Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules had almost identical magnetic susceptibilities of 1.2×10−4 emu g−1 Oe−1.

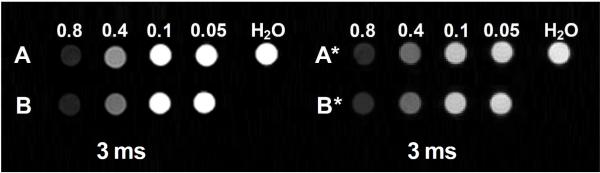

We performed in vitro MR assays (T2 and T2* weighted imaging) in 0.5% agarose gel for both types of Gd2O2S:Tb and Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules with a series of concentration (0.8 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, 0.1 mg/ml, and 0.05 mg/ml). Fig. 9 shows T2 and T2* weighted images after 3 ms. the proton relaxivities r2 of the nanocapsules was determined from the longitudinal and transverse relaxation rates at various concentrations. These relaxation rates are shown as a function of concentration in Fig. S13. The relaxivities, r2 and r2* are 50.3 mM−1s−1 and 116.0 mM−1s−1 respectively for Gd2O2S:Tb nanocapsules; 51.7 mM−1 s−1 and 116.4 mM−1s−1 for Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules.

Fig. 9.

T2 and T2*-weighted images of radioluminescent nanocapsules. Group A: T2-weighted images of Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules with concentration of 0.8 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, 0.1 mg/ml, and 0.05 mg/ml. Group B: T2-weighted images of Gd2O2S:Tb with concentration of 0.8 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, 0.1 mg/ml, and 0.05 mg/ml. Group A*: T2*-weighted images of Gd2O2S:Eu nanocapsules with concentration of 0.8 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, 0.1 mg/ml, and 0.05 mg/ml. Group B*: T2*-weighted images of Gd2O2S:Tb nanocapsules with concentration of 0.8 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, 0.1 mg/ml, and 0.05 mg/ml.

For these nanocapsules, r2* is larger than r2 due to the inhomogeneities of local static field from the magnetic moment of the particles. Previous work towards the gadolinium nanoparticles (e.g. ultrasmall Gd2O3 nanoparticles (1~10 nm)50,53. and hollow nanosparticles with thin Gd2O3 shell (~10 nm)54.) reported that they can served as good T1 contrast agents and moderate T2 contrast agents. However, our nanocapsules with a ~25 nm Gd2O2S based nanoshell worked as a better T2 contrast agents than many reported Gd2O3 nanoparticles (r2=14.1~16.9 mM−1s−1)55-57. and gadolinium chelates (Gd-DOTA, 4.9 mM−1s−1)55.. In addition, the T2 relaxivities value of our nanocapsules is similar to FDA-approved iron oxide nanoparticle contrast agents such as Ferumoxtran (Resovist®, 65 mM−1s−1), cross-linked iron oxide particle (CLIO-Tat, 62 mM−1s−1), and water soluble iron oxide (WSIO, 78 mM−1s−1).58-61.

Conclusion

In summary, we present a flexible template-directed method to produce radioluminescent nanocapsules for a hydrophilic drug carrier and monitor release kinetics. The release rate time constant was ~ 36 days at pH 7.4, and 21.4 hr at pH 5.0, respectively. Importantly, the release mechanisms could be monitored in situ by tracking the ratio of radioluminescence spectral peaks. Radioluminescence offers several advantages over traditional optical imaging agents, including greater tissue penetration, elimination of autofluorescence, and the ability to perform high-resolution imaging through thick tissue via functional X-ray Luminescence Tomography (FXLT)30, 32, 34, 36.. Finally, the multifunctional nanocapsules combined the advantages of positive contrast of radioluminescence and negative contrast of T2 weighted MR imaging. These capabilities provide these nanocapsules to enable novel drug delivery and imaging modalities. In future, we plan to target DOX loaded capsules to tumors and measure in situ release rates and tumor growth for various nanocapsule sizes, shapes, and surface chemistries.

Experimental Section

Materials

Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), poly(styrenesulfonate sodium) (PSS, MW:~70,000), Iron (III) chloride anhydrous was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Gadolinium nitrate, europium nitrate, and poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH, MW:~15,000) were purchased from obtained from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Ethanol (96%), urea, oxalic acid, ammonium hydroxide, and nitric acid were obtained from BDH Chemicals Ltd (Poole, Dorset, UK). Deionized (DI) water was purchased from EMD Chemicals Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K-30, MW 40,000) was purchased from Spectrum Chemicals (Gardena, CA). Agarose (melting point 88±1 °C) was purchased from Shelton Scientific (Peosta, IA). All chemicals were used as received without further purification.

Preparation of nanocapsules (Gd2O2S:Tb and Gd2O2S:Eu)

Monodispersed spindle-shaped hematite nanotemplate with controllable aspect ratios were fabricated were prepared according to the method described by Ozaki and coworkers.43. Typically, 100 ml of aqueous solution containing 2.0×10−2 M FeCl3 and 3.0×10−4 M KH2PO4 were aged at 100 °C for 72 hours. The resulting precipitate was centrifuged and washed three times with water. The hollow silica shell was obtained according to the literatures.37, 62-63. The spindle-shaped hematite particles synthesized above were dispersed ultrasonically to a 80 ml solution containing PVP (0.6 g), water (6 ml), and ethanol (74 ml). The suspension was stirred using a magnetic stir bar at room temperature and a solution of TEOS (270 μl) in 20 ml ethanol was added, followed by 4 ml of ammonia hydroxide. After 3h, the reaction mixture was precipitated by centrifuging at 4000 rpm for 16 min. The particles were washed three times with ethanol and centrifuged to collect the product. These silica coated hematite nanoparticles were then suspended in 180 ml distilled water with 1.8 g PVP and 11.34 g oxalic acid (0.5 M) and incubated at 60 °C for 17h in order to dissolve the hematite core. The silica shell particles were collected by centrifugation and rinsed with DI water twice. The obtained hollow nanoshells were resuspended with 3 ml Gd(NO3)3, 0.94 ml Tb(NO3)3 (80 mM) or 1.5 ml Eu(NO3)3 (80 mM), and 1.8 g PVP in pure water to form 300 ml of solution. 18 g of urea was added to the solution and the solution was maintained at 80 °C for 60 min. The precursor of radioluminescent nanocapsules were collected by centrifugation and calcined in a furnace at 600 °C for 60 min. The powder was then transferred to a tube furnace with a sulphur/argon flow at 900 °C for 60 min. The obtained nanocapsules were re-heated at 400 °C in the air for 1 h and incubated in distilled water (2.5 mg/ml) at 100 °C for 2 h prior to use.

Preparation of polyelectrolyte multilayer coating

2 ml of PSS with concentration of 5 mg mL−1 in 0.5 M NaCl was added to a 10 ml aqueous suspension (pH 6) of 50 mg DOX and 30 mg nanocapsules (Gd2O2S:Tb). After ultrasonic treatment for 10 min, the suspension was collected by centrifugation and washed three times in distilled water. Gentle shaking followed by ultrasonic treatment for 1 min was used to disperse the particles after centrifugation. Then, the particles was resuspended in 2 ml oppositely charged PAH (5 mg mL−1 in 0.5M NaCl) with 50 mg DOX and socnicated for 10 min. The PSS coating process was repeated for eight times and the PAH coating was repeated for 7 times. Finally a composite of DOX-nanocapsules coated with PAH/PSS multilayers was obtained.

In vitro HPLC drug-release study and real-time drug release tacking

100 μl of DOX encapsulated nanocapsules with polyelectrolyte mutilayers (10 mg/ml) were suspended with release media (7 ml) at pH 5.0 and 7.4 in Slide-A-Lyzer MINI dialysis units at room temperature. The release medium was removed for analysis at given time intervals, and replaced with the same volume of fresh release medium. The DOX concentration was measured with high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Waters system using an Alltima C18 column (250×4.6 mm, 5 μm).

Radioluminescence drug release tracking experiment

2 ml DOX encapsulated nanocapsules with polyelectrolyte multilayers (25 mg/ml) were magnetically stirred at a rate of 400 rpm in release media of either pH 5 or pH 7.4. 50 μl of the solution was taken out for X-ray luminescence analysis without any separation at given time intervals.

Preparation of nanocapsules for MR Imaging

T2 and T2* MR measurements were acquired for the spindle-shaped SiO2@Gd2O2S:Eu and Gd2O2S:Tb particles at a series of concentrations (0.8 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml, 0.1 mg/ml, and 0.05 mg/ml). The particles were dispersed in 0.5% agarose gel at 80 °C and cooled to room temperature in NRM tubes to set the gel. The gel prevented settling and aggregation allowing MRI imaging several days after preparation.

Cell viability test

MCF-7 breast cancer cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in a 96 well plate. Cells were stored at 37 °C at 5% CO2 and attached to the plate overnight. Nanocapsules were suspended in media, sonicated for 10 minutes to disperse, and diluted to 250, 100, 50, and 10 μg/ml. Media was removed from wells and fresh media or nanoparticle in media was added to each well. Five repeats were done for each concentration. Nanoparticles were incubated with cells overnight and the next day a Presto Blue assay (Life Technologies) was performed. Media was removed and 100 μl of a 1:9 ratio Presto Blue in culture media was added to each well. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 45 minutes. Fluorescent intensity was taken with a plate reader with an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm. Fluorescent intensity for each concentration of nanoparticle was normalized as a percentage of the fluorescent intensity of the control cells. Percent viability averages were plotted with error bars of one standard deviation.

Characterization methods

Transmission and scanning electron microscopy (TEM) were performed on a H9500 operated at 200 kV and HD2000 microscope operated at 20 kV, respectively. Powder XRD patterns were obtained on a Rigaku diffractometer at 40 kV and 40 mA (CuKα radiation). For fluorescence spectra, 480 nm light was used to excite the scintillators. To measure radioluminescence, X-ray was generated by a mini X-ray tube (Amptek Inc. MA, USA), the X-ray tube was operated with tube voltage of 40 kV and tube current of 40 mA. The sample was mounted on a Leica Microscope (Leica DMI 5000M, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a DeltaNu DNS 300 spectrometer (Intevac-DeltaNu, Laramie, WY USA) with a 150 lines/mm grating blazed at 500 nm and with a cooled CCD camera (iDUS-420BV, Andor, South Windsor, CT). X-ray luminescence images were captured in an IVIS Lumina XR Imaging System (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, US) with 0.1 s exposure time. Bright field and fluorescent images were taken on a Nikon microscope (Eclipse Ti, Nikon, Melville, NY USA). Determination of the Zeta potential of the nanoparticles was performed via a Zetasizer Nano ZS (with a 633 nm He-Ne laser) from Malvern Instrument. Prior to the experiment, the particles were diluted in distilled water (0.1 mg/ml). Magnetization measurements were performed at the designated temperature using vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) option of physical property measurement system (PPMS, Quantum Design, USA), with the applied magnetic field sweeping between +/− 3.0 Tesla at a rate of 50 Oe/sec. Determination of the gadolinium content in a sample was performed by inductively coupled plasma (ICP)- (Optima 3100 RL; Perkin-Elmer). All MRI experiments were performed on a Varian 4.7T horizontal bore imaging system (Agilent Inc, Santa Clara, CA). Samples, contained in 5 mm NMR tubes, were placed in a 63 mm inner diameter quadrature RF coil for imaging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by The Center of Biomaterials for Tissue Regeneration (CBTR) funded under NIH grants 5P20RR021949 and 8P20GM103444. We thank the Clemson University Electron Microscope Facility for use of TEM imaging facilities. We also thank Professor Shiou-Jyh Hwu for use of his furnace.

Footnotes

Supporting information Supporting information including figures to address the characterization in terms of spectroscopy, electron microscopy images, toxicity, magnetic hysteresis, and magnetic resonance relaxivities. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Zhu Y, Shi J, Shen W, Dong X, Feng J, Ruan M, Li Y. Stimuli-Responsive Controlled Drug Release from a Hollow Mesoporous Silica Sphere/Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Core–Shell Structure Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5083–5087. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shchukin DG, Sukhorukov GB, Möhwald H. Smart Inorganic/Organic Nanocomposite Hollow Microcapsules Angew. Chem. 2003;115:4610–4613. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sukhorukov G, Dähne L, Hartmann J, Donath E, Möhwald H. Controlled Precipitation of Dyes into Hollow Polyelectrolyte Capsules Based on Colloids and Biocolloids Adv. Mater. 2000;12:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibarz G, Dähne L, Donath E, Möhwald H. Smart Micro- and Nanocontainers for Storage, Transport, and Release. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:1324–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi S-W, Zhang Y, Xia Y. A Temperature-Sensitive Drug Release System Based on Phase-Change Materials. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:8076–8080. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong B, Bae YH, Kim SW. Drug Release from Biodegradable Injectable Thermosensitive Hydrogel of PEG–PLGA–PEG Triblock Copolymers. J. Controlled Release. 2000;63:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li YL, Zhu L, Liu Z, Cheng R, Meng F, Cui JH, Ji SJ, Zhong Z. Reversibly Stabilized Multifunctional Dextran Nanoparticles Efficiently Deliver Doxorubicin into the Nuclei of Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9914–9918. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito G, Swanson JA, Lee KD. Drug Delivery Strategy Utilizing Conjugation via Reversible Disulfide Linkages: Role and Site of Cellular Reducing Activities. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2003;55:199–215. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C, Chen Q, Wang Z, Zhang X. An Enzyme Responsive Polymeric Superamphiphile. Angew. Chem. 2010;122:8794–8797. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olson ES, Jiang T, Aguilera TA, Nguyen QT, Ellies LG, Scadeng M, Tsien RY. Activatable Cell Penetrating Peptides Linked to Nanoparticles as Dual Probes for in Vivo Fluorescence and MR Imaging of Proteases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:4311–4316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910283107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardos A, Aznar E, Marcos MD, Martínez Máñez R, Sancenón F, Soto J, Barat JM, Amorós P. Enzyme-Responsive Controlled Release Using Mesoporous Silica Supports Capped with Lactose. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:5998–6001. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skirtach AG, Muñoz Javier A, Kreft O, Köhler K, Piera Alberola A, Möhwald H, Parak WJ, Sukhorukov GB. Laser-Induced Release of Encapsulated Materials inside Living Cells. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:4728–4733. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You J, Zhang G, Li C. Exceptionally High Payload of Doxorubicin in Hollow Gold Nanospheres for Near-Infrared Light-Triggered Drug Release. ACS Nano. 2010;4:1033–1041. doi: 10.1021/nn901181c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu G, Mikhailovsky A, Khant HA, Fu C, Chiu W, Zasadzinski JA. Remotely Triggered Liposome Release by Near-Infrared Light Absorption via Hollow Gold Nanoshells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8175–8177. doi: 10.1021/ja802656d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong H, Zhang Y, Sun J, Cai W. Molecular Imaging and Therapy of Cancer with Radiolabeled Nanoparticles. Nano Today. 2009;4:399–413. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z, Cai W, He L, Nakayama N, Chen K, Sun X, Chen X, Dai H. In Vivo Biodistribution and Highly Efficient Tumour Targeting of Carbon Nanotubes in Mice. Nat. Nano. 2007;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang F, Zhu L, Liu G, Hida N, Lu G, Eden HS, Niu G, Chen X. Multimodality Imaging of Tumor Response to Doxil. Theranostics. 2011;1:302–309. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaszczak RJ, Coleman RE, Whitehead FR. Physical Factors Affecting Quantitative Measurements Using Camera-Based Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (Spect) IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1981;28:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morelli D, Ménard S, Colnaghi MI, Balsari A. Oral Administration of Anti-Doxorubicin Monoclonal Antibody Prevents Chemotherapy-Induced Gastrointestinal Toxicity in Mice. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2082–2085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Hoff DD, Layard MW, Basa P, Davis JHL, Von Hoff AL, Rozencweig M, Muggia FM. Risk Factors for Doxorubicin-Induced Congestive Heart Failure. Ann. Intern. Med. 1979;91:710–717. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-5-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin: Review of Animal and Human Studies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–436. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee ES, Na K, Bae YH. Doxorubicin Loaded pH Sensitive Polymeric Micelles for Reversal of Resistant MCF-7 Tumor. J. Controlled Release. 2005;103:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee ES, Na K, Bae YH. Super pH Sensitive Multifunctional Polymeric Micelle. Nano Lett. 2005;5:325–329. doi: 10.1021/nl0479987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson J, Rosenholm J, Areva S, Lindén M. Influences of Material Characteristics on Ibuprofen Drug Loading and Release Profiles from Ordered Micro-and Mesoporous Silica Matrices. Chem. Mater. 2004;16:4160–4167. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbé C, Bartlett J, Kong L, Finnie K, Lin HQ, Larkin M, Calleja S, Bush A, Calleja G. Silica Particles: A Novel Drug Delivery System. Adv. Mater. 2004;16:1959–1966. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, Jeftinija K, Xu S, Jeftinija S, Victor SYL. A Mesoporous Silica Nanosphere-Based Carrier System with Chemically Removable CdS Nanoparticle Caps for Stimuli-Responsive Controlled Release of Neurotransmitters and Drug Molecules. J. Am.Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu Y, Shi J, Shen W, Dong X, Feng J, Ruan M, Li Y. Stimuli-Responsive Controlled Drug Release from a Hollow Mesoporous Silica Sphere/Polyelectrolyte Multilayer Core-Shell Structure. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:5213–5217. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpenter CM, Sun C, Pratx G, Liu H, Cheng Z, Xing L. Radioluminescent Nanophosphors Enable Multiplexed Small-Animal Imaging. Opt. Express. 2012;20:11598–11604. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.011598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun C, Pratx G, Carpenter CM, Liu H, Cheng Z, Gambhir SS, Xing L. Synthesis and Radioluminescence of PEGylated Eu3+-Doped Nanophosphors as Bioimaging Probes. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:H195–H199. doi: 10.1002/adma.201100919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pratx G, Carpenter CM, Sun C, Lei X. X-ray Luminescence Computed Tomography via Selective Excitation: A Feasibility Study. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2010;29:1992–1999. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2010.2055883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pratx G, Carpenter CM, Sun C, Rao RP, Xing L. Tomographic Molecular Imaging of X-ray Excitable Nanoparticles. Opt. Lett. 2010;35:3345–3347. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.003345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter C, Sun C, Pratx G, Rao R, Xing L. Hybrid X-ray/Optical Luminescence Imaging: Characterization of Experimental Conditions. Med. Phys. 2010;37:4011–4018. doi: 10.1118/1.3457332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpenter CM, Pratx G, Sun C, Xing L. Limited-Angle X-ray Luminescence Tomography: Methodology and Feasibility Study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011;56:3487–3502. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/12/003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, Patrick AL, Yang Z, VanDerveer DG, Anker JN. High-Resolution Chemical Imaging through Tissue with an X-ray Scintillator Sensor. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:5045–5049. doi: 10.1021/ac200054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H, Rogalski MM, Anker JN. Advances in Functional X-ray Imaging Techniques and Contrast Agents. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012;14:13469–13486. doi: 10.1039/c2cp41858d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Longfield DE, Varahagiri VS, Nguyen KT, Patrick AL, Qian H, VanDerveer DG, Anker JN. Optical Imaging in Tissue with X-ray Excited Luminescent Sensors. Analyst. 2011;136:3438–3445. doi: 10.1039/c0an00931h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H, Colvin DC, Qi B, Moore T, He J, Mefford OT, Alexis F, Gore JC, Anker JN. Magnetic and Optical Properties of Multifunctional Core-Shell Radioluminescence Nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. 2012;22:12802–12809. doi: 10.1039/C2JM15444G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Decuzzi P, Godin B, Tanaka T, Lee SY, Chiappini C, Liu X, Ferrari M. Size and Shape Effects in the Biodistribution of Intravascularly Injected Particles. J. Controlled Release. 2010;141:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gratton SEA, Ropp PA, Pohlhaus PD, Luft JC, Madden VJ, Napier ME, DeSimone JM. The Effect of Particle Design on Cellular Internalization Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:11613–11618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801763105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Champion JA, Mitragotri S. Role of Target Geometry in Phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:4930–4934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang X, Li L, Liu T, Hao N, Liu H, Chen D, Tang F. The Shape Effect of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles on Biodistribution, Clearance, and Biocompatibility in Vivo. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5390–5399. doi: 10.1021/nn200365a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishikawa T, Matijevic E. Formation of Monodispersed Pure and Coated Spindle-Type Iron Particles. Langmuir. 1988;4:26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozaki M, Kratohvil S, Matijević E. Formation of Monodispersed Spindle-Type Hematite Particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1984;102:146–151. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piao Y, Kim J, Na HB, Kim D, Baek JS, Ko MK, Lee JH, Shokouhimehr M, Hyeon T. Wrap-Bake-Peel Process for Nanostructural Transformation from β-FeOOH Nanorods to Biocompatible Iron Oxide Nanocapsules. Nat. Mater. 2008;7:242–247. doi: 10.1038/nmat2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franz KA, Kehr WG, Siggel A, Wieczoreck J, Adam W. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; KGaA: 2000. Luminescent Materials. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okumura M, Tamatani M, Matsuda N, Takahara T, Fukuta Y. Ceramic Scintillator, Method for Producing Same, and X-ray Detector and X-ray CT Imaging Equipment Using Same. 6,384,417 U.S. Patent. 2002

- 47.van Eijk CWE. Inorganic Scintillators in Medical Imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2002;47:R85–R106. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/8/201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmaljohann D. Thermo- and pH Responsive Polymers in Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2006;58:1655–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee ES, Gao Z, Bae YH. Recent Progress in Tumor pH Targeting Nanotechnology. J.Controlled Release. 2008;132:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petoral RM, Söderlind F, Klasson A, Suska A, Fortin MA, Abrikossova N, Selegård L. a., Käll P-O, Engström M, Uvdal K. Synthesis and Characterization of Tb3+-Doped Gd2O3 Nanocrystals: A Bifunctional Material with Combined Fluorescent Labeling and MRI Contrast Agent Properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:6913–6920. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park JY, Baek MJ, Choi ES, Woo S, Kim JH, Kim TJ, Jung JC, Chae KS, Chang Y, Lee GH. Paramagnetic Ultrasmall Gadolinium Oxide Nanoparticles as Advanced T1 MRI Contrast Agent: Account for Large Longitudinal Relaxivity, Optimal Particle Diameter, and In Vivo T1 MR Images. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3663–3669. doi: 10.1021/nn900761s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahrén M, Selegård L, Klasson A, Söderlind F, Abrikossova N, Skoglund C, Bengtsson T, Engström M, Käll P-O, Uvdal K. Synthesis and Characterization of PEGylated Gd2O3 Nanoparticles for MRI Contrast Enhancement. Langmuir. 2010;26:5753–5762. doi: 10.1021/la903566y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi Z, Neoh KG, Kang ET, Shuter B, Wang SC. Bifunctional Eu3+-Doped Gd2O3 Nanoparticles as a Luminescent and T1 Contrast Agent for Stem Cell Labeling. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2010;5:105–111. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang C-C, Liu T-Y, Su C-H, Lo Y-W, Chen J-H, Yeh C-S. Superparamagnetic Hollow and Paramagnetic Porous Gd2O3 Particles. Chem. Mater. 2008;20:3840–3848. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bridot J, Faure A, Laurent S, Riviére C, Billotey C, Hiba B, Janier M, Josserand V, Coll J, Vander Elst L, et al. Hybrid Gadolinium Oxide Nanoparticles: Multimodal Contrast Agents for in Vivo Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5076–5084. doi: 10.1021/ja068356j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDonald MA, Watkin KL. Investigations into the Physicochemical Properties of Dextran Small Particulate Gadolinium Oxide Nanoparticles. Acad. Radiol. 2006;13:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fortin M, R. MP, Jr, Söderlind F, Klasson A, Engström M, Veres T, Käll P, Uvdal K. Polyethylene Glycol-Covered Ultra-Small Gd2O3 Nanoparticles for Positive Contrast at 1.5 T Magnetic Resonance Clinical Scanning. Nanotechnology. 2007;18 395501(1-9) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y, Hussain S, Krestin G. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Contrast Agents: Physicochemical Characteristics and Applications in MR Imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2001;11:2319–2331. doi: 10.1007/s003300100908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Josephson L, Tung C, Moore A, Weissleder R. High-Efficiency Intracellular Magnetic Labeling with Novel Superparamagnetic-Tat Peptide Conjugates. Bioconj. Chem. 1999;10:186–191. doi: 10.1021/bc980125h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jun Y, Huh Y, Choi J, Lee J, Song H, Kim K, Yoon S, Kim K, Shin J, Suh J, et al. Nanoscale Size Effect of Magnetic Nanocrystals and Their Utilization for Cancer Diagnosis via Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5732–5733. doi: 10.1021/ja0422155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jun Y, Seo J, Cheon J. Nanoscaling Laws of Magnetic Nanoparticles and Their Applicabilities in Biomedical Sciences. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:179–189. doi: 10.1021/ar700121f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lou XW, Archer LA. A General Route to Nonspherical Anatase TiO2 Hollow Colloids and Magnetic Multifunctional Particles. Adv. Mater. 2008;20:1853–1858. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen JS, Chen C, Liu J, Xu R, Qiao SZ, Lou XW. Ellipsoidal Hollow Nanostructures Assembled from Anatase TiO2 Nanosheets as a Magnetically Separable Photocatalyst. Chem. Comm. 2011;47:2631–2633. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04471g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.