Abstract

An increasing number of lipid mediators have been identified as key modulators of immunity. Among these is a family of glycolipids capable of cellular uptake, loading onto the MHC-like molecule CD1d and stimulation of NKT cells. NKT cells are particularly interesting because they bridge innate and adaptive immunity by coordinating the early events of dendritic cell maturation, recruitment of NK cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells, and B cells at the site of microbial injury. As such, their therapeutic manipulation could be of the greatest interest in vaccine design or active immunotherapy. However, the use of NKT cells as cellular adjuvant of immunity in the clinic will require a better knowledge of the pharmacology of lipid agonists in order to optimize their action and avoid potential unseen off-target effects. We have been studying extracellular transport and cellular uptake of NKT agonists for the past few years. This field is confronted to a very limited prior knowledge and a small set of usable tools. New technology must be put in place and adapted to answering basic immunology questions related to NKT cells.

The intimate link between the pharmacology of glycolipids and lipid metabolism makes us believe that great variations of bioactivity could be seen in the general population when NKT agonists are use therapeutically.

Keywords: NKT cells, vaccine, lipid transport, cellular uptake, degradation, scavenger receptors

Introduction

The recognition of lipids and glycolipids is restricted by a family of MHC-like molecules called CD1 that have evolved away from MHC by acquiring a very hydrophobic groove capable of accommodating the acyl chains of a large number of lipids. Because so many bacterial PAMPs are lipids, CD1-restricted responses are very important in anti-microbial defenses. Upon binding to CD1, a particular subset of glycolipids stimulates a very small semi-invariant population of T cells called Natural Killer T cells (NKT cells). NKT cells are very important lymphocytes in both rodents and man as they have the unique property of coordinating the early events of dendritic cell (DC) maturation, recruitment of NK cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells and B cells at the site of initial insult. This function of “Cellular Adjuvanticity” is mediated by direct interactions (with DC and B cells), and the rapid secretion of cytokines such as IL-4 and IFN-γ. It was recently realized that this physiological property of NKT cells could be exploited to develop a new family of adjuvants of immunity. Accordingly, a number of glycolipids based on the structure of α - galactosylceramide (α GalCer) have been developed, tested in animal models and are currently entering the arena of clinical testing. Because they are glycolipids, the knowledge of the pharmacology of these molecules is still very limited. We contend that the successful use of NKT agonists in the clinic will rely heavily on a better understanding of their transport, cellular uptake and degradation, as dyslipidemia are one of the most common metabolic conditions.

Current Status

Transport

Because heart diseases are so prevalent and so intimately linked to dyslipidemia, most of our knowledge about the transport of lipids has been acquired in this context and focused almost exclusively on cholesterol metabolism. In immunology, lipid mediators of inflammation (prostaglandins and leukotrienes) have long been known, but it is only recently that lipids have been examined for their potential therapeutic value with the discovery of sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1-P) and its role in immune cell trafficking. This particular discovery was followed by an explosion of research in the field: isolation of a series of cellular receptors, detailed description of the metabolic pathways leading to synthesis and degradation of S1-P, accessibility of each pathway to agonistic or antagonistic interventions. Our particular field of interest, the physiology of glycolipids, is a lot less explored. Some older publications have examined the transport of gangliosides but none have been placed in an immunological context. One recent exception has examined lipoprotein association and cellular uptake of digalactosylceramide antigens. In this elegant paper, αGal(α1–2)GalCer was shown to require binding to very low density lipoprotein(VLDL) particles and subsequent uptake via the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) in an apolipoprotein E (apoE)-dependent manner to intersect the CD1 presentation pathway and activation of NKT cells1. However, this particular antigen has not been the focus of further chemical development and therapeutic attention.

Systematic studies, development of new tools

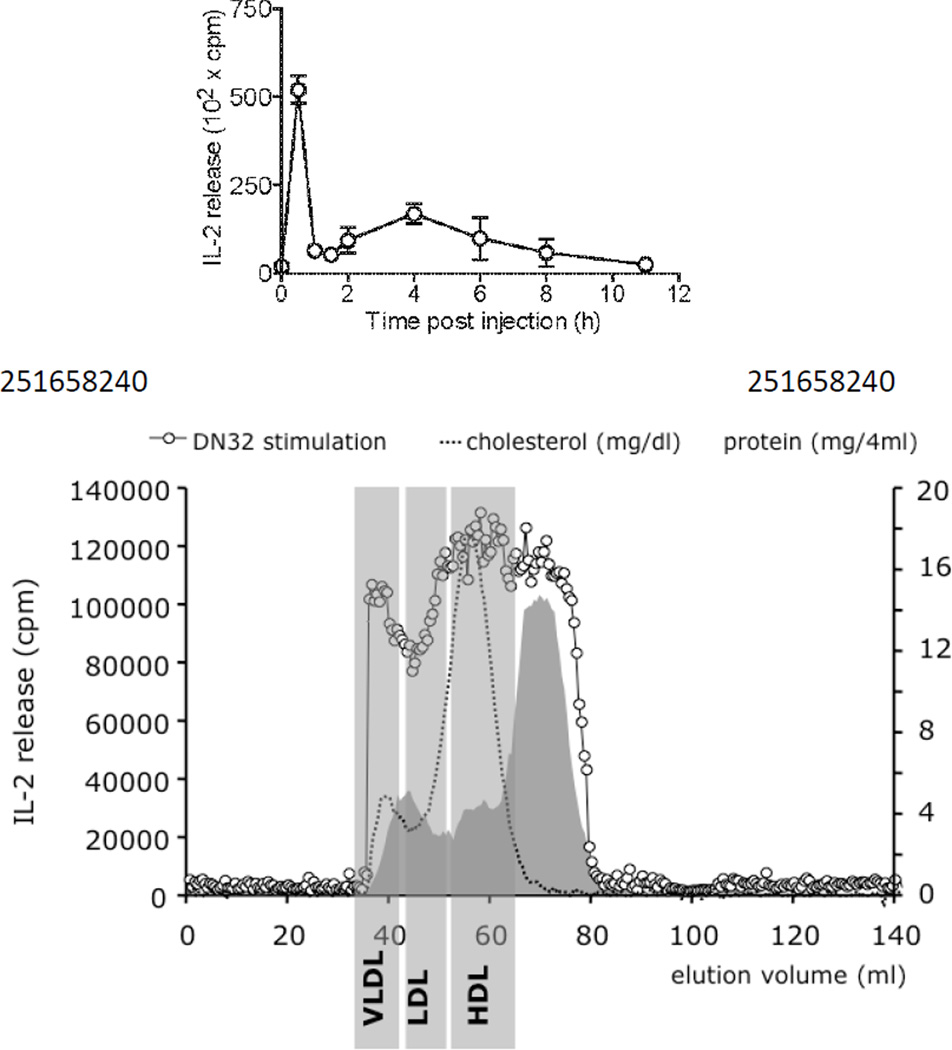

Because so many clinical trials making use of α GalCer variants are ongoing2, we thought that we needed unbiased techniques to examine extracellular transport and cellular metabolism of α GalCer. Our first attempts were based on old-fashion traditional biochemistry. Mice were injected with α GalCer and sampled over time to determine the kinetics of NKT stimulatory activity in the serum; this approach determined that after a short 20–30min phase of circulation following I.V. injection, stimulatory activity was disappearing for the next 2 hours to slowly reappear 3–4h after injection. Our interpretation of this phenomenon was that α GalCer was trafficking to the liver, and packaged with lipoproteins before being transported to the periphery. We examined mouse serum collected 4h after injection by a series of classical chromatography columns to separate fractions where stimulatory activity would be concentrated. Similar experiments were carried out ex vivo by mixing α GalCer with normal mouse serum; they yielded very similar conclusions (Figure 1). Not surprisingly we found α GalCer associated to VLDL and HDL, and to a very large extent to non-particulate fractions where monomeric proteins would be present (Figure 1). Further fractionation of stimulatory peaks never isolated single proteins. One particular fraction with high stimulatory activity was analyzed by trypsin digestion and mass spectrometry and revealed the presence of fatty acid amid hydrolase (FAAH). FAAH is present in the liver and many immune cells at high concentration but is supposed to be cytoplasmic and not secreted. However, biochemical techniques confirmed the presence of this enzyme in the serum of normal mice. Recombinant FAAH was then used to demonstrate the capacity of the enzyme to bind α GalCer and transfer it onto CD1. Furthermore, the FAAH knockout mouse exhibited an unusual phenotype when challenged with α GalCer and antigen. At low doses of α GalCer, knockout mice were more responsive to NKT driven vaccination than wild type mice and could survive subsequent bacterial challenge, despite making less detectable circulating IFNγ. What the entire study revealed is twofold3. Firstly, classical techniques could isolate α GalCer-binding proteins, secondly, some of these proteins could help understand the biology of NKT agonists. In the particular case of FAAH, one of the most interesting phenotype was the dissociation between serum IFN levels and amplitude of the immune response. Indeed, we intuitively correlate the magnitude of IFN secretion with the potency of NKT agonists, whereas the FAAH experiment would indicate the opposite and suggest that only local cytokine secretion is of interest for the efficacy of NKT agonist.

Figure 1.

Tracing the bioactivity of α GalCer in serum. Top: C57/BL6 mice were injected with 1 µ g α GalCer and sampled at various time points to follow the bioactivity of diluted serum towards the DN.32 NKT cell hybridoma. Bottom: repartition of the α GalCer bioactivity in serum after separation over a gel filtration column (open dots). Total cholesterol and protein concentrations are indicated as well as the position of VLDL, LDL, and HDL. In both cases in vitro-matured BMDC were used as antigen presenting cells. IL-2 production by NKT cells was measured at 24h.

New Tools

However, the classical biochemical techniques to study α GalCer transport also demonstrated their limitations: slow, cumbersome, costly, poorly discriminative, labor intensive. We wanted to pursue our investigation of serum transport of α GalCer with more powerful tools. Because the C6 position of α GalCer is permissive to chemical modifications, we decided to attach an accessible tag to this position and use the modified glycolipid for affinity purification. This compound, called PBS-11X, was incubated with serum at 37°C for various lengths of time and pulled out using streptavidin columns. The bound material was separated by SDS-PAGE gel and analyzed after trypsin digestion by mass spectrometry. In three separate experiments, a total of 40 proteins were identified as being the core binding proteome of PBS-11X. Not surprisingly the list of proteins included all the lipoproteins, the major lipid transport proteins among which LBP, CD14 and saposins. Multiple complement components were also identified, as well as a list of unexpected proteins such as paraoxonase, Q10, clusterin, and CXCL4. The later 4 proteins are currently being investigated individually by combining recombinant protein expression and direct binding experiments and in vivo studies in knockout mice. An interesting phenotype has already been revealed in the CXCL4 KO mouse as it appears that CXCL4 is an important component required for the transport and uptake of α GalCer in vivo. Beyond the details of each of these studies, a general principle is emerging for studying transport of NKT ligands: probes can be designed for affinity studies in whole serum and exploited for proteomic studies. The same probes can be used for both mouse and human and it should be reasonably straightforward to examine the main classes of NKT agonists that one may want to use in the clinic: α GalCer-derived lipids, lyso-glycolipids, di- or tri-saccharide glycolipids. Further studies should focus on gene products that are known to be polymorphic in man and/or susceptible to spontaneous or induced modifications, e.g paraoxonase, and capable of modifying the effectiveness of NKT based therapies.

Uptake

Early Studies

Studying uptake of α GalCer revealed the same challenges than studying transport: few tools, old tools. Our first approach was to use the small collection of knockout mice that were produced to study lipoprotein uptake and biology, CD36, LDLR, Lox-1, SRA, SCARB-1, and use cells from these mice for α GalCer presentation in vitro. The first important conclusion that came from these studies was that often phenotypes would not be revealed by using the heterogeneous mixture that are splenocytes, but instead required bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC). The second and more important lesson was that, like for transport, small chemical modifications of a glycolipid such as addition of one unsaturation on the acyl chain or modification of the head group could alter uptake in major ways. Using this archaic approach we, nonetheless, determined that the uptake of α GalCer depended on LDLR to some extent but mainly on SRA4. The same phenotype that was uncovered in vitro was confirmed in vivo in LDLR and SRA KO mice. In vivo studies revealed an additional important feature associated to uptake: differential cytokine secretion linked to the efficiency of uptake. Indeed, it has long been known that most NKT agonists could induce the secretion of both IL-4 and IFN-γ but the mechanisms supporting the dissociation between these 2 cytokines have never been fully understood: lipid chain lengths supporting different cellular trafficking, different target cells, strength of agonism once bound to CD1d? From studying uptake of α GalCer in LDLR and SRA KO mice, it appeared that the most important factor to drive IL-4 secretion was the efficiency of uptake: 2 receptors were better than one, SRA was better than LDLR. It is to our knowledge the first time that one could dissociate IL-4 and IFN-γ secretions for the same NKT agonist by simply modifying cellular uptake. This is an important conclusion that by itself justifies further studies of NKT agonist uptake4.

Next Steps

However, using KO mice to study the uptake of more than one glycolipid offers major challenges: number of lines, number of mice, costs, in vivo experiments; these limiting factors are not suited to an academic environment with finite resources. As a first alternative, we explored the usage of a collection of blocking antibodies against each known receptor; the strategy worked well and phenocopied some results obtained in KO mice but the number of available antibodies is still limiting and needs to be expanded to make this approach a viable option. Complementary to this first technology, we are also producing soluble forms of the same collection of lipid and lipoprotein receptors to carry out direct binding studies in vitro.

Our second approach was the direct extension of the transport studies and took advantage of the same reagents. By exploring various families of detergents, we have determined conditions in which PBS-11X can be used for affinity experiments in cell extracts. The direct binding of FAAH to α GalCer was confirmed using this approach. The preparation of plasma and endosomal membranes should allow us to examine the binding proteome of PBS-11X/α GalCer from membrane binding to CD1d-loading compartments.

Chemistry Dominates Transport and Uptake

We have now learned from both types of studies that subtle changes in the chemical nature of a glycolipid can alter its transport and/or its uptake. By surveying a large number of NKT agonists with a wide chemical coverage, we can also conclude that no particular chemical signature can be used to predict a particular serum behavior or receptor uptake. For instance, some traits, such as the presence of a negative charge on the head group, favor the uptake by SRA but α GalCer has no charge on its sugar and uses SRA as its main receptor. In other words, it will be necessary to examine each potential clinical candidate for its transport and cellular entry.

Degradation

It has been long known that the prolonged stimulation of NKT cells was leading to their depletion through activation induced cell death and apoptosis. In the clinical context, this particular situation is problematic whenever a particular regimen and treatment has to be applied multiple times in close succession like for example vaccination. One side of the issue that has not been examined in much detail and that probably controls to a large extent the duration of stimulation that a particular NKT agonist exerts, is degradation. Again, and that is the recurring theme of our studies, good tools have been missing to study this issue. Indirect assays such as the isolation of various antigen presenting cells from animals following administration of NKT agonists and stimulation of reporter NKT cell lines can be used, and have taught us that stimulatory activity was persistent for more than 48h. However, direct evaluation of metabolism is finally accessible through the use of metabolomics. In our case, we have determined conditions for the direct detection of α GalCer and its main metabolites (fatty acid, α - psychosine, sphingosine and galactose) from cells using mass spectrometry. The sensitivity of detection allows reproducible results from 1×106 cells and is amenable to in vitro and ex vivo studies. This approach should allow us to quantify the metabolism and α GalCer and explore chemistry that could influence degradation and help produce shorter-lived agonists.

Future Perspectives

As the technology slowly falls in place, we have in hands a platform that allows us to examine transport, uptake and degradation not only in mice but also in human. This molecular pharmacology of NKT agonists is of the greatest interest not only because it is technically challenging, but also because it teaches us some fundamental aspects of glycolipid biology. Ultimately, we believe that this effort will help us rationalize and optimize the usage of the ever-expanding NKT agonist family in the clinic.

Highlights.

We have explored the serum transport of glycolipids

Glycolipids transport is influenced by their chemical composition

Chemistry also influences cellular uptake

Therapeutic applications of glycolipids will depend heavily on lipid homeostasis

Lipid biology will guide immunotherapy with NKT cells

Acknowledgments

Project supported by NIH (NIAID AI053725-10). The project has been carried our by Stefan Freigang and Lisa Kain with the technical support of TSRI core facilities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.van den Elzen P, et al. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 2005;437:906–910. doi: 10.1038/nature04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneiders FL, et al. Clinical experience with alpha-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with advanced cancer and chronic hepatitis B/C infection. Clin Immunol. 2011;140:130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freigang S, et al. Fatty acid amide hydrolase shapes NKT cell responses by influencing the serum transport of lipid antigen in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:1873–1884. doi: 10.1172/JCI40451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freigang S, et al. Scavenger receptors target glycolipids for NKT cell activation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012 doi: 10.1172/JCI62267. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]