Abstract

Background

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended an “opt-out” human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing strategy in 2006 for all persons aged 13 to 64 years at healthcare settings. We conducted this study to identify individual, health, and policy factors that may be associated with HIV testing in US adults.

Methods

The 2008 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System data were utilized. Individuals’ residency states were classified into 4 categories based on the legislation status to HIV testing laws in 2007 and HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome morbidity. A multivariate logistic regression adjusting for survey designs was performed to examine factors associated with HIV testing.

Results

A total of 281,826 adults aged 18 to 64 years answered HIV testing questions in 2008. The proportions of US adults who had ever been tested for HIV increased from 35.9% in 2006 to 39.9% in 2008. HIV testing varied across the individual’s characteristics including sociodemographics, access to regular health care, and risk for HIV infection. Compared with residents of “high morbidity-opt out” states, those living in “high morbidity-opt in” states with legislative restrictions for HIV testing had a slightly lower odds of being tested for HIV (adjusted odds ratio = 0.96; 95% confidence interval = 0.92, 1.01). Adults living in “low morbidity” states were significantly less likely to be tested for HIV, regardless of legislative status.

Conclusions

To implement routine HIV testing in the general population, the role of public health resources should be emphasized and legislative barriers should be further reduced. Strategies need to be developed to reach people who do not have regular access to health care.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection presents an important public health problem as 1.1 million people in the United States are living with HIV and new infections occur at an annual rate of 22.8 cases per 100,000 people.1,2 About 21% of those infected are not aware of their status and may transmit HIV in the community.2 In addition, diagnosis at a late stage is common among newly diagnosed patients, an indication of missed opportunities to detect HIV in an early stage and prevent further transmission.3 Therefore, enhanced strategies for HIV prevention are needed to reflect the dynamics of HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic in the United States.4,5 In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended a routine “opt-out” HIV testing strategy in healthcare settings.6 Under this strategy, healthcare providers inform patients aged 13 to 64 years about the test and can then proceed with HIV testing unless the patient refuses; a separate written consent form for HIV testing and pretest counseling are not necessary.

The CDC’s strategy has led some states to modify their laws, resulting in more people tested for HIV.7–18 For example, a streamlined consent process is associated with a 30% increase in HIV testing among high-risk people, and undiagnosed HIV infections at the early stage have been detected by nontargeted HIV screening conducted at an emergency department.14,17 The routine opt-out HIV testing may also reduce social stigma associated with HIV testing and increase patients’ acceptance as the test is being offered to every eligible individual. Nonetheless, some legal, logistical, and ethical issues limit the implementation of the opt-out HIV testing in the general population.10,19–27 The Institute of Medicine has concluded that the barriers for opt-out HIV testing included legislative restrictions to HIV testing, inconsistent federal recommendations, health insurance policies, and the lack of clinician education and training.27 Consequently, more research is needed to better understand factors related to HIV testing in the general population.

The results from previous national surveys show that less than 50% of adults aged 18 to 64 years reported ever being tested for HIV, and the majority of those tested received HIV testing at a clinical setting.16,28–30 A history of HIV testing is associated with an individual being younger, female, belonging to a non- Hispanic black race, of low socioeconomic status, and having high-risk behaviors for HIV infection.16,28–30 At the policy level, legislation requiring a separate written consent form may be associated with a lower testing rate; thus, removal of the legislative restriction may improve HIV testing.8–10,18,27,31 In addition, several federal agencies allocated funding in 2007 to increase HIV testing. Particularly, the CDC has funded expanded and integrated HIV testing projects to state and local health departments in 26 jurisdictions with a goal to test 1.5 million people.32 In summary, legislative action, public health resources, and individual factors should be considered in assessing HIV-testing behaviors in order to develop effective strategies to encourage routine HIV screening in the general population.

We conducted this study with the objectives to (1) describe the prevalence of HIV testing among US adults aged 18 to 64 years; (2) identify individual characteristics associated with HIV testing; and (3) assess the impacts of legislation and public health resources on HIV testing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

We used data from the 2008 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System (BRFSS) for this study.33 The BRFSS is an ongoing nationwide survey using computer-assisted telephone interviewing to collect behavioral information from adults aged 18 years or older. Currently, 50 US states, the District of Columbia (DC), Puerto Rico, Guam, and the US Virgin Islands participate in the BRFSS. Adults older than 64 years or living outside 50 US states and the DC were excluded from the analysis.

The BRFSS survey questionnaire contains the core component asked by all states, as well as optional modules and state-added questions. The core component includes questions about demographics, perceived health conditions, and health-related behaviors.

Variables of Interest

Three comparable questions regarding HIV testing (“Have you ever been tested for HIV” excluding blood donation, “Month and year of last HIV test,” and “Where did you have your last HIV test”) were asked in the core component for all adults aged 18 to 64 years after 1996. In 2008, a question regarding high-risk situations that may facilitate acquisition of HIV infection was also asked to respondents to indicate if they had any following situations in the past year: using intravenous drugs, being treated for a sexually transmitted disease, exchanging sex for money or drug, or having anal sex without a condom. In this study, we focused on whether an adult reported having ever been tested for HIV as a main outcome.

To examine the role of legislative status and public health resources, we first categorized individual’s state of residency as “opt-in” and opt-out based on the legislation regarding HIV testing on January 1, 2007.7,10 A total of 20 states (AZ, CA, CT, HI, IL, IN, LA, IA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NM, NY, NC, PA, RI, and WI) requiring a separate written consent form for HIV testing among nonpregnant adults were classified as opt-in states, whereas the remaining 31 states and the DC were classified as opt-out. Second, we stratified states into “high” and “low morbidity” based on CDC’s funding areas for the expanded HIV testing project; 21 states and the DC with a high burden of AIDS cases among blacks (≥140 cases in 2005) were eligible for the expanded HIV testing project and then grouped as “high-morbidity” states (AL, CA, CT, DC, FL, GA, IL, LA, MD, MA, MI, MS, MO, NJ, NY, NC, OH, PA, SC, TN, TX, and VA), and the rest 29 states were grouped as “low-morbidity” states.32 Finally, we classified individual’s states into the following 4 categories according to both methods: “high morbidity-opt out” (12 states), “high morbidity-opt in” (10 states), “low morbidity-opt out” (19 states), and “low morbidity-opt in” (10 states).

We also examined individual’s characteristics related to HIV testing, which included sociodemographics (age, sex, race-ethnicity, marital status, children in the household, education, employment, income, and county of residency), healthcare access (healthcare coverage, personal doctor, time interval since last routine checkup, and “could not see doctor because of cost”), self-perception (perceived general health status, social and emotional support, and life satisfaction), and high-risk situations for HIV. Individual’s county of residency was classified as “rural” and “urban” based on the 2003 rural-urban continuum codes defining metropolitan statistical area (MSA) counties provided by the Economic Research Service.34

Statistical Analyses

We adjusted the analyses for the survey design based on the final weight assigned to each respondent.33 In the descriptive analyses to depict the characteristics of US adults in the BRFSS 2008, we used the Rao-Scott χ2 test to assess statistical significance of the association between HIV testing and variables of interest. We included individuals with a missing HIV-testing outcome (“ever been tested for HIV”) in the analysis by combining them with the “no” category. We fit the data using a multivariate logistic regression, with being tested for HIV as the dependent variable, and the remaining variables of interest as independent predictors. We also evaluated several 2-way interactions between variables and retained the significant interaction (2-sided tests at P < 0.05) in the model. We used the SAS software system version 9.2 procedure SURVEYLOGISTIC (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) to fit this model, adjusting for the survey design, and obtained the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) to examine the significant associations between being tested for HIV and independent predictors at P < 0.05.

Because we found substantial missing data (up to 10%) in some of the variables and deletion of the data from the analysis may have caused selection bias, we incorporated multiple imputations into the calculation of estimates under the assumption that the missing data mechanism was missing at random.35 We included all of the predictor variables plus the dependent variable in the model to impute the missing predictor values, assuming multivariate normality. We imputed missing values using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method, and created 5 imputed data sets, and conducted the multivariate analyses on each data set and combined results.35

We also conducted sensitivity analyses on 2 different scenarios. Under the first scenario, we excluded respondents with missing data in the predictors from the analysis. Under the second scenario, we removed respondents with a missing outcome (ever been tested for HIV) from the analysis, and compared the “yes” category with the “no” category. We then compared the 3 additional sets of parameters resulting from combining these modifications against each other to determine observable divergence in the associations.

RESULTS

In 2008, 281,826 US adults aged 18 to 64 years responded to the BRFSS; 39.9% of them reported ever being tested for HIV (35.9% in 2006 BRFSS, P < 0.0001), and 10.6% of them underwent an HIV testing in the past 12 months (9.7% in 2006 BRFSS). Private doctor or HMO (41.6%), clinic (25.4%), and hospital (16.6%) were the major sources of testing, followed by correctional facilities (9.2%), counseling and testing site (3.8%), and home testing (3.4%). Only 3.6% of US adults reported having any high-risk situations for HIV infection.

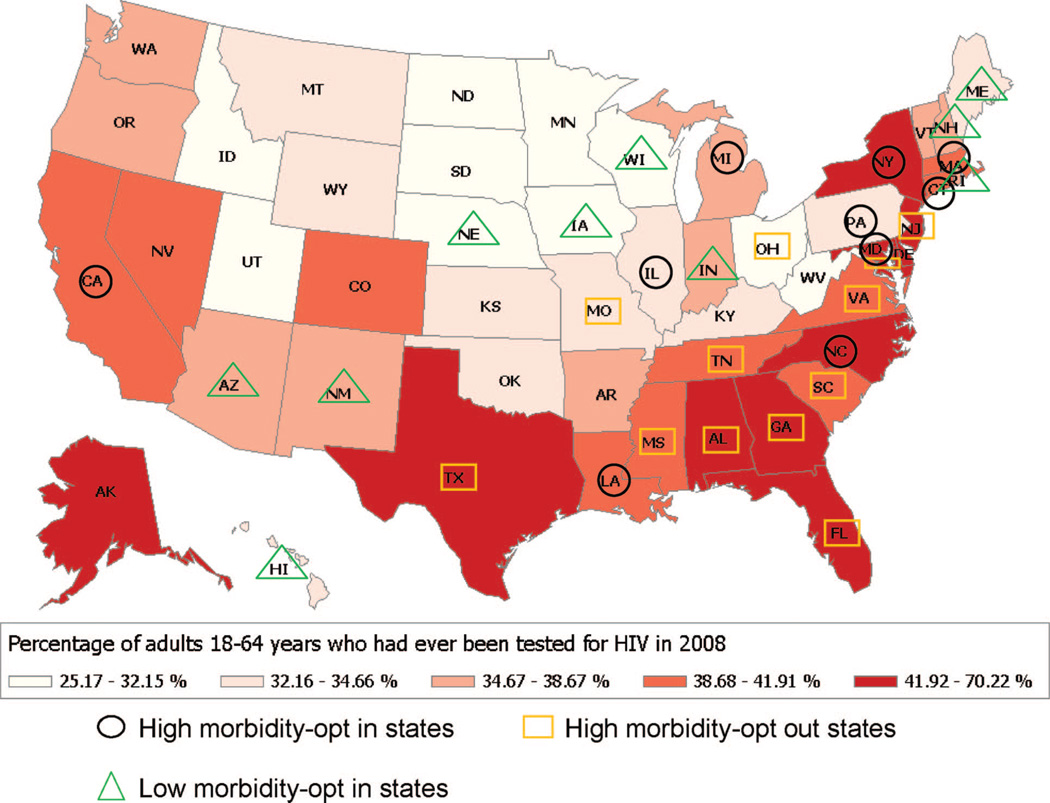

A substantial variation in the prevalence of adults who had ever been tested for HIV was seen across US states, ranging from 25.2% in Utah to 70.2% in DC (Fig. 1). States with a higher testing prevalence were mainly in the South and Northeast regions with high HIV/AIDS burdens. Among the top 10 states for HIV testing, 7 of them were opt-out states, whereas only Maryland, North Carolina, and New York were opt-in states in which a separate consent form for HIV testing was required as of 2007. The prevalence of HIV testing was lower than the national level in 4 high-morbidity states (IL, MI, MO, and PA), of which 3 were opt-in states.

Figure 1.

The percentage of adults aged 18 to 64 years who had ever been tested for HIV by US state, BRFSS 2008.

Table 1 shows the weighted prevalence of HIV testing which differed across the individual’s sociodemographic characteristics. About 50% of adults aged 25 to 34 years had been tested for HIV, but only 20% of those older than 55 years reported HIV testing. In younger age groups (<45 years), more females had been tested for HIV, whereas in older age groups (≥45 years) more males had been tested. A higher testing prevalence was observed among adults who were non-Hispanic blacks (59.5%) and Hispanics (41.1%), single (40.2%), and had annual household income less than $15,000 (43.2%). The testing prevalence was lower among adults with a high-school degree or less (35.0%), those without a dependent child (31%), and residents living in a non-MSA county (31.9%).

TABLE 1.

HIV Testing Among US Adults Aged 18–64 Years, BRFSS 2008

| Characteristics | N (Weighted %*) | Ever Been Tested for HIV N (Weighted %)† |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 281,826 | 96,430 (39.9) |

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Female | 172,257 (49.9) | 61,355 (41.0) |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 7515 (7.1) | 3127 (39.7) |

| 25–34 | 24,653 (11.0) | 14,565 (59.8) |

| 35–44 | 37,202 (11.4) | 18,628 (51.1) |

| 45–54 | 50,728 (11.6) | 15,608 (31.3) |

| 55–64 | 52,159 (8.8) | 9427 (18.6) |

| Male | 109,569 (50.1) | 35,075 (34.9) |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 6006 (7.8) | 1428 (24.2) |

| 25–34 | 13,972 (11.1) | 5800 (42.9) |

| 35–44 | 23,457 (11.5) | 9945 (44.3) |

| 45–54 | 32,099 (11.3) | 10,067 (32.8) |

| 55–64 | 34,035 (8.4) | 7835 (24.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic/white | 218,772 (66.5) | 67,759 (33.9) |

| Non-Hispanic/black | 23,660 (10.4) | 13,013 (59.5) |

| Hispanic | 20,144 (15.8) | 8271 (41.1) |

| Other | 17,136 (7.3) | 6610 (37.1) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/a member of an unmarried couple | 178,394 (65.3) | 55,612 (36.8) |

| Never married/divorced/widowed/separated | 102,545 (34.7) | 40,533 (40.2) |

| Children less than 18 yr of age in the household | ||

| None | 165,127 (48.9) | 45,129 (31.0) |

| 1 or more | 116,043 (51.1) | 51,142 (44.7) |

| Educational level | ||

| High school or less | 99,564 (38.5) | 30,419 (35.0) |

| Some college or technical school | 77,953 (27.0) | 28,054 (40.0) |

| College graduate | 103,722 (34.5) | 37,887 (39.9) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed for wages/self-employed | 196,709 (69.6) | 66,782 (38.0) |

| Unemployed/retired/other | 84,166 (30.4) | 29,451 (38.4) |

| Annual household income | ||

| <$15,00 | 23,028 (9.0) | 10,023 (43.2) |

| $15,000–50,000 | 100,476 (38.3) | 34,887 (40.1) |

| >$50,000 | 131,571 (52.7) | 44,478 (37.6) |

| County of residency | ||

| Rural: non-MSA county | 101,140 (20.8) | 29,621 (31.9) |

| Urban: MSA county | 174,569 (79.2) | 64,711 (39.8) |

| Healthcare access | ||

| Have any kind of healthcare coverage | ||

| Yes | 241,435 (82.0) | 81,921 (37.6) |

| No | 39,774 (18.0) | 14,383 (39.7) |

| Have a personal doctor or healthcare provider | ||

| Yes | 234,645 (77.7) | 79,552 (37.8) |

| No | 46,580 (22.3) | 16,724 (38.7) |

| Could not see a doctor because of cost in the past 12 mo | ||

| Yes | 40,613 (16.0) | 17,432 (46.3) |

| No | 240,699 (84.0) | 78,849 (36.4) |

| Length of time since last routine checkup | ||

| Within the past year | 187,449 (64.5) | 65,663 (39.6) |

| Within the past 2–5 yr | 63,529 (25.0) | 21,793 (36.2) |

| 5 or more years ago | 24,468 (8.8) | 7121 (32.8) |

| Never | 3514 (1.7) | 975 (30.0) |

| Self-perception | ||

| Perceived general health status | ||

| Excellent/very good/good | 237,074 (86.1) | 79,858 (37.6) |

| Fair/poor | 43,857 (13.9) | 16,264 (40.4) |

| Emotional support | ||

| Always/usual/sometimes | 252,373 (92.5) | 87,699 (38.9) |

| Rarely/never | 19,137 (7.5) | 7434 (41.3) |

| Life satisfaction | ||

| Very satisfied/satisfied | 255,819 (94.4) | 87,566 (38.4) |

| Dissatisfied/very dissatisfied | 16,665 (5.6) | 7694 (49.9) |

| Any high-risk situations for HIV | ||

| Yes | 6759 (3.6) | 4286 (66.3) |

| No | 262,423 (96.4) | 91,365 (41.0) |

| Residency state type | ||

| High morbidity-opt out (N = 12) | 65,201 (34.3) | 24,513 (40.2) |

| High morbidity-opt in (N = 10) | 73,700 (40.1) | 27,419 (38.9) |

| Low morbidity-opt out (N = 19) | 93,557 (15.7) | 29,612 (33.5) |

| Low morbidity-opt in (N = 10) | 49,368 (9.8) | 14,886 (33.0) |

Column percent, missing values were not included.

Row percent; a missing response to HIV testing was combined with the “No” category.

HIV indicates human immunodeficiency virus; BRFSS, behavioral risk factors surveillance system.

There was no noticeable difference in the prevalence of HIV testing between adults with healthcare coverage and those without, but the prevalence was higher among adults who could not see a doctor because of the cost (46.3%). A clear decline in testing prevalence was detected regarding the length of time since the last routine checkup; the prevalence was 39.6% among adults who had a routine checkup within the past year, but decreased to 30% among those who never had a routine checkup. The prevalence of HIV testing was higher among adults who perceived fair or poor health status (40.4%), rarely or never received social and emotional support (41.3%), were unsatisfied with their lives (49.9%), and had any high-risk situations for HIV infection (66.3%). In relation to the residency state type, the highest testing prevalence was seen among adults living in high morbidity-opt out states (40.2%), followed by the prevalence among those living in high morbidity-opt in states (38.9%), and the lowest prevalence was observed among residents of low morbidity-opt in states (33.0%).

Table 2 demonstrates factors associated with being tested for HIV. The unadjusted odds ratios obtained from the bivariate analysis provided an initial assessment of factors associated with HIV testing. In the final multivariate analysis, statistically significant factors in the bivariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model, and multiple imputations were incorporated to adjust for missing values. In the multivariate model, the age-sex interaction indicated that females were more likely to be tested than males in younger age groups but less likely to be tested in older age groups. Adults who were non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics, single, could not see a doctor because of the cost, perceived fair/poor health, perceived life dissatisfaction, and had any high-risk situations for HIV were significantly more likely to be tested; whereas adults who had no dependent child, had low educational attainment, lived in a rural county, did not have a recent routine checkup, or never had a routine checkup were significantly less likely to be tested for HIV.

TABLE 2.

Factors Associated With HIV Testing Among US Adults Aged 18–64 Years, BRFSS 2008

| Ever Been Tested for HIV Infection* |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Bivariate Analysis Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariate Analysis Adjusted Odds Ratio† (95% CI) |

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age-sex interaction (vs. male) | ||

| Age, 18–24; female | 2.07 (1.82, 2.35) | 1.93 (1.69, 2.21) |

| Age, 25–34; female | 1.98 (1.84, 2.13) | 1.76 (1.63, 1.90) |

| Age, 35–44; female | 1.31 (1.24, 1.39) | 1.19 (1.12, 1.27) |

| Age, 45–54; female | 0.93 (0.88, 0.99) | 0.88 (0.83, 0.93) |

| Age, 55–64; female | 0.72 (0.67, 0.77) | 0.67 (0.63, 0.72) |

| Race/ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic white) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.85 (2.70, 3.01) | 2.47 (2.33, 2.62) |

| Hispanic | 1.36 (1.28, 1.44) | 1.19 (1.11, 1.27) |

| Other | 1.15 (1.07, 1.23) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.10) |

| Never married/divorced/widowed/separated (vs. married/unmarried couple) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) | 1.27 (1.22, 1.33) |

| No child less than 18 yr of age in the household (vs. 1 or more) | 0.56 (0.54, 0.57) | 0.75 (0.72, 0.78) |

| Educational level (vs. college graduate) | ||

| High school or less | 0.81 (0.78, 0.84) | 0.74 (0.71, 0.77) |

| Some college or technical school | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) |

| Unemployed/retired/other (vs. employed) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) |

| Annual household income (vs. >$50,000) | ||

| <$15,000 | 1.26 (1.18, 1.35) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) |

| $15,000–50,000 | 1.11 (1.07, 1.15) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) |

| Rural county residency (vs. urban) | 0.71 (0.69, 0.74) | 0.80 (0.77, 0.84) |

| Healthcare access | ||

| Not having any kind of healthcare coverage | 1.09 (1.04, 1.15) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.02) |

| Not having a personal doctor or healthcare provider | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.07) |

| Could not see a doctor because of cost in the past 12 mo | 1.51 (1.45, 1.59) | 1.38 (1.30, 1.46) |

| Length of time since last routine checkup (vs. within the past year) | ||

| Within the past 2–5 yr | 0.87 (0.83, 0.90) | 0.80 (0.77, 0.83) |

| 5 or more years ago | 0.74 (0.70, 0.79) | 0.68 (0.64, 0.73) |

| Never | 0.65 (0.56, 0.76) | 0.58 (0.49, 0.69) |

| Self-perception | ||

| Perceived fair/poor general health status (vs. excellent to good) | 1.13 (1.08, 1.18) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.22) |

| Rarely/never get emotional support | 1.11 (1.03, 1.18) | 0.94 (0.87, 1.02) |

| Life dissatisfaction | 1.60 (1.50, 1.72) | 1.44 (1.33, 1.55) |

| Any high-risk situations for HIV | 2.83 (2.55, 3.13) | 2.40 (2.15, 2.67) |

| Residency state type (vs. high morbidity: opt-out states) | ||

| High morbidity: opt-in (N = 10) | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) |

| Low morbidity: opt-out (N = 19) | 0.75 (0.72, 0.78) | 0.89 (0.85, 0.92) |

| Low morbidity: opt-in (N = 10) | 0.73 (0.69, 0.77) | 0.85 (0.80, 0.90) |

A missing response to HIV testing was combined with the “No” category.

A multiple imputation was incorporated in the multivariate analysis to adjust for missing data in individual characteristics under the assumption of missing at random.

HIV indicates human immunodeficiency virus; BRFSS, behavioral risk factors surveillance system.

Compared with residents of high morbidity-opt out states, those living in high morbidity-opt in states with legislative restrictions for HIV testing had a slightly lower odds of being tested for HIV, but the association was not statistically significant (aOR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.92, 1.01) (Table 2). Adults living in low-morbidity states were significantly less likely to be tested for HIV, regardless of legislative status (aORs = 0.89 and 0.85, respectively).

Additional sensitivity analyses suggested that the modification with the outcome variable by excluding “missing” value in HIV testing did not appreciably alter the results, except that the association between “not having any kind of healthcare coverage” and being tested for HIV became statistical significant (aOR = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.89, 0.99). However, excluding missing values in predictors resulted in a substantial reduction in sample size decreasing from 281,826 to 231,443 respondents, and the aORs between race, income, healthcare access, and HIV testing were noticeably exaggerated. More important, the aOR between living in high morbidity-opt in states and being tested for HIV was reversed (aOR = 1.41; 95% CI = 1.34, 1.47).

DISCUSSION

In 2008, about 40% of US adults aged 18 to 64 years had ever been tested for HIV, representing a 4% increase compared with the proportion in 2006. After the CDC released the revised recommendations for HIV testing, some state health departments have been actively seeking modification to their public health laws to eliminate the written consent form or simplify the consent process in order to incorporate routine HIV testing into medical care.7,10 HIV testing in the general population may also be promoted by the federally funded expanded HIV testing projects.13 Therefore, this increase in HIV testing may have resulted from compliance with the CDC’s opt-out HIV testing strategy after 2006 as well as the efforts of expanded HIV-testing projects conducted in multiple states since 2007.

Our study showed that the highest prevalence of HIV testing was reported by adults living in high morbidity-opt out states, supporting that an opt-out strategy would improve HIV testing in the general population. The nonsignificant difference in HIV testing between residents of high morbidity-opt out and high morbidity-opt in states could be because a simplified consent process has been adapted to promote HIV testing in several opt-in states (e.g., CA, NY, NC), although the state public health law for HIV testing has not been officially amended. The results also indicated that the residents of low morbidity states were significantly less likely to be tested for HIV. Because these low morbidity states were allocated less HIV-prevention funding by the CDC and were also not eligible for the expanded HIV-testing project, the lack of public health resources may be a critical barrier for HIV testing.24,32,36,37

Despite the important increase in HIV testing between 2006 and 2008, nearly 60% of adults have never been tested for HIV, even among those living in states without legislative restrictions for HIV testing. As only 3.6% of US adults reported any high-risk situations for HIV infection in 2008, perception of “no risk” for HIV infection seems a main reason for not being tested for HIV.38 We also observed a significant reduction in HIV testing as the length of time since last routine checkup increased, implying that limited utilization of or access to regular health care may account for not being tested as well. Additional analyses showed that reporting of high-risk situations for HIV was more prevalent among adults without regular healthcare access (i.e., no health insurance coverage, no personal doctor, could not see doctor because of the cost, or no recent or never had routine checkup); thus, new strategies need to be developed to reach high-risk people outside the healthcare settings.

Other new findings from our study are also worthy of mentioning. First, a noticeable rural-urban difference in HIV testing was observed; rural county residents were less likely to be tested for HIV. The BRFSS 2008 data also showed that rural residents were less likely to have health insurance coverage and more likely to have prolonged interval for routine checkup, but after adjusting for healthcare access indicators and high-risk situations for HIV infection, the rural-urban difference was still significant, suggesting that additional barriers including insufficient public health resources may impede HIV testing among rural residents.39 Previous research also demonstrates that rural residents, compared with urban counterparts, are more likely to have HIV diagnosed late40; thus, HIV testing efforts should be expanded to rural areas. Second, we found a significant age-sex interaction in HIV testing; women were more likely to be tested than men in younger age groups, but less likely to be tested in older age groups. This interaction may be the result of the implementation of routine prenatal HIV-testing screening which has been recommended by the CDC since 1995. However, the risk of HIV infection should not be neglected for women aged 45 to 64 years.

Our study has several limitations. First, although the BRFSS is the largest population-based telephone survey, response rates have been decreasing and the rates also vary across states, ranging from 35.8% in Maryland to 65.9% in Kentucky in 2008 (median response rate = 53.5%).41 In addition, households without telephone coverage and a growing number of those with only cellular phone were not included in the BRFSS sampling frame. The 2008 BRFSS Summary Data Quality Report showed that the respondents were more likely to be female, non-Hispanic white, or aged 45 years or older, than the US general population. As a result, HIV testing behaviors may be underestimated in this study due to potential selection bias. Second, the state type is defined based on the 2007 legislative status for HIV testing; however, a streamlined consent process that resembles the opt-out strategy has been developed in some opt-in states after 2006 to promote HIV testing, although the HIV-testing laws have not been officially modified. It is also possible that people living in an opt-out state may not remember being tested for HIV if they did not go through the consent process. Therefore, the differences in the prevalence of HIV testing between opt-out and opt-in states may be underestimated.31

In conclusion, HIV testing in the general population has increased from 2006 to 2008, while many people have never been tested. Consistent with previous national surveys, HIV testing varies by individual’s sociodemographics and perceived risk profiles for HIV infection. As healthcare settings are still a major source of HIV testing and people may be more likely to accept HIV testing upon physician’s recommendation,17,42–45 clinicians will play an important role in promoting HIV screening, regardless of individual’s risk for HIV infection. Our study also suggests that the public health resource is a critical factor in implementing routine HIV testing, and therefore sustained federal funding is needed. Removal of the written consent might facilitate HIV testing, especially in states with a high HIV/AIDS burden. However, new healthcare- and policy-directed strategies need to be developed to reach people who are less likely to be tested, including older women and those in high-morbidity, opt-out, and rural areas.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant K12HD055882 and “Career Development Program in Women’s Health Research at Penn State” from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant U54 HD34449 (to P.D., K12 scholar).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1512–1520. doi: 10.1086/652650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branson B. Current HIV epidemiology and revised recommendations for HIV testing in health-care settings. J Med Virol. 2007;79(suppl 1):S6–S10. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton KA. Changing epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the United States: Implications for enhancing and promoting HIV testing strategies. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S213–S220. doi: 10.1086/522615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE1–CE4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compendium of State HIV Testing Laws. 2010 Available at: http://www.nccc.ucsf.edu/consultation_library/state_hiv_testing_laws/

- 8.Mahajan AP, Stemple L, Shapiro MF, et al. Consistency of state statutes with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV testing recommendations for health care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:263–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf LE, Donoghoe A, Lane T. Implementing routine HIV testing: The role of state law. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett JG, Branson BM, Fenton K, et al. Opt-out testing for human immunodeficiency virus in the United States: Progress and challenges. JAMA. 2008;300:945–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Conroy AA, et al. Routine opt-out rapid HIV screening and detection of HIV infection in emergency department patients. JAMA. 2010;304:284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Screening for HIV in health care settings: A guidance statement from the American College of Physicians and HIV Medicine Association. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:125–131. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expanded HIV testing and trends in diagnoses of HIV infection—District of Columbia, 2004–2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:737–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zetola NM, Grijalva CG, Gertler S, et al. Simplifying consent for HIV testing is associated with an increase in HIV testing and case detection in highest risk groups, San Francisco January 2003–June 2007. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen RS. Implementing HIV screening. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S226–S231. doi: 10.1086/522542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: HIV testing and diagnosis among adults—United States, 2001–2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1550–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, et al. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:435–442. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wing C. Effects of written informed consent requirements on HIV testing rates: Evidence from a natural experiment. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1087–1092. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke RC, Sepkowitz KA, Bernstein KT, et al. Why don2019;t physicians test for HIV? A review of the US literature. AIDS. 2007;21:1617–1624. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32823f91ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Fichtenbaum CJ, et al. Interpreting and implementing the 2006 CDC recommendations for HIV testing in health-care settings. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:579–583. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtgrave DR. Costs and consequences of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendations for opt-out HIV testing. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanssens C. Legal and ethical implications of opt-out HIV testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S232–S239. doi: 10.1086/522543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheever LW, Lubinski C, Horberg M, et al. Ensuring access to treatment for HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S266–S274. doi: 10.1086/522549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munar DE. Funding and implementing routine testing for HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S244–S247. doi: 10.1086/522545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kates J, Levi J. Insurance coverage and access to HIV testing and treatment: Considerations for individuals at risk for infection and for those with undiagnosed infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S255–S260. doi: 10.1086/522547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein KT, Begier E, Burke R, et al. HIV screening among U.S. physicians, 1999–2000. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:649–656. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. HIV screening and access to care: Exploring barriers and facilitators to expanded HIV testing. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV testing—United States, 2001. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:540–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Persons tested for HIV—United States, 2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:845–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson JE, Carey JW, Taveras S. HIV testing among the general US population and persons at increased risk: Information from national surveys, 1987–1996. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1089–1095. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ehrenkranz PD, Pagan JA, Begier EM, et al. Written informed-consent statutes and HIV testing. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Expanded and integrated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing for populations disproportionately affected by HIV, primarily African Americans. 2007 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/od/pgo/funding/PS07–768.htm.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey data. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.2003 Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2004 Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/Rural UrbanContinuumCodes/

- 35.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley-IEEE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linas BP, Zheng H, Losina E, et al. Assessing the impact of federal HIV prevention spending on HIV testing and awareness. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1038–1043. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penner M, Leone PA. Integration of testing for, prevention of, and access to treatment for HIV infection: State and local perspectives. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(suppl 4):S281–S286. doi: 10.1086/522551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liddicoat RV, Losina E, Kang M, et al. Refusing HIV testing in an urgent care setting: Results from the “Think HIV” program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:84–92. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton M, Anthony MN, Vila C, et al. HIV testing and HIV/AIDS treatment services in rural counties in 10 southern states: Service provider perspectives. J Rural Health. 2010;26:240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, et al. Associations of rural residence with timing of HIV diagnosis and stage of disease at diagnosis, South Carolina 2001–2005. J Rural Health. 2010;26:105–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008 BRFSS summary data quality reports. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Byyny RL. Patient acceptance of rapid HIV testing practices in an urban emergency department: Assessment of the 2006 CDC recommendations for HIV screening in health care settings. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:303–309. 309e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandez MI, Bowen GS, Perrino T, et al. Promoting HIV testing among never-tested Hispanic men: A doctor’s recommendation may suffice. AIDS Behav. 2003;7:253–262. doi: 10.1023/a:1025491602652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coleman VH, Anderson JR, Schulkin J. A comparison of patient perceptions and physician practice patterns related to HIV testing. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:604–610. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e318181a4a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petroll AE, DiFranceisco W, McAuliffe TL, et al. HIV testing rates, testing locations, and healthcare utilization among urban African-American men. J Urban Health. 2009;86:119–131. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9339-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]