Abstract

We recently reported a novel anticancer small molecule, designated FL118, which was discovered via high throughput screening (HTS), and followed by hit-lead in vitro and in vivo analysis. FL118 selectively inhibits the expression of four major cancer survival-associated gene products (survivin, Mcl-1, XIAP, and cIAP2) and shows promising antitumor activity in animal models of human cancers when administered using a weekly x 4 schedule (Ling et al., PLOS ONE. 2012, 7: e45571). Here, we compared the antitumor efficacy and therapeutic index (TI) of FL118 in a newly developed Tween 80-free formulation that can be delivered intravenously (i.v.) and intraperitoneally (i.p.) against the previous Tween 80-containing formulation that can only be delivered via an i.p. route. We found that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for FL118 in the i.v. formulation increases 3-7 fold in comparison with the MTD of FL118 in the i.p. formulation. FL118 in the i.v. recipe was able to eliminate human tumor xenografts in all three major schedules tested (daily x 5, q2 x 5 and weekly x 5). In contrast, FL118 was able to eliminate human tumor xenografts in the i.p. formulation only with the weekly x 4 schedule previously reported. The TI of FL118 in the i.v. formulation reached 5-6 in the most effective schedule, while the TI of FL118 in the i.p. formulation was only 1.3 - 2. These findings overcome several clinical challenges including FL118 formulation to realize clinically compatible drug administration routes, and expanding effective treatment schedules. The striking improvement of the TI makes FL118 a much safer drug for further development toward clinical trials.

Keywords: FL118, maximum tolerated doses (MTD), antitumor activity, human tumor animal model, intravenous (i.v.), intraperitoneal (i.p.)

Introduction

Resistance of cancer cells to treatment is the ultimate cause of cancer relapse due to the failure to eradicate cancer cells that possess multiple survival mechanisms upon treatment. Protein members in the inhibitor-of-apoptosis (IAP) and Bcl-2 families are major cancer-associated survival factors which play critical roles in treatment (drug and radiation) resistance. Specifically, survivin, an IAP member, is a pivotal molecule at the junction of cancer cell survival and division networks [1,2], and an inherent and induced drug/radiation resistance factor for various cancer types during treatment [3-21]. Mcl-1, a Bcl-2 family antiapoptotic protein, also plays important roles in cancer cell survival and resistance to drug/radiation treatment [22-35]. In addition, XIAP [36-45] and cIAP2 [27,46-50], both IAP family members, also play roles in cancer cell resistance and survival.

We have recently reported a novel antitumor small chemical molecule, FL118, which was discovered via high throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries, followed by hit-to-lead in vitro and in vivo analysis [51]. FL118 selectively inhibits the expression of four cancer-associated gene products (survivin, Mcl-1, XIAP, cIAP2) in the IAP and Bcl-2 families [51]. Consistent with its versatile feature to target multiple cancer survival/proliferation-associated factors, we have shown that in a weekly x 4 schedule using its maximum tolerated dose (MTD) by the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route, FL118 shows striking antitumor activity in both human colon and head-&-neck cancers in animal models [51]. However, the i.p. route is not a clinical conventional route and may only be used for ovarian cancer patients. Instead, the intravenous (i.v.) injection of anticancer drugs is a common route in clinical practice. In this regard, we have developed a new i.v.-compatible formulation for FL118 which is Tween 80 free. In this study, we compared the antitumor efficacy and therapeutic index (TI) of FL118 in the newly developed i.v. formulation with that of FL118 in the previously tested i.p.-compatible formulation containing 10 - 20% of Tween 80. We found that FL118 in the i.v. formulation shows a much lower toxicity, and the MTD of FL118 is strikingly increased (MTD: 1.5 to 10 mg/kg in different schedules) in comparison with that of FL118 in the i.p. formulation (0.2 to 1.5 mg/kg in different schedules). FL118 in the i.v. formulation is able to eliminate xenograft tumors in animal models in all schedules tested, while FL118 in the i.p. formulation is unable to eliminate tumors in most schedules except in the weekly x 4 schedule previously described [51]. Furthermore, FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation improved its TI more than 3 fold. These findings indicate that the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation makes FL118 a much safer antitumor drug. This new clinically-compatible i.v. formulation overcomes a big challenge for FL118 in regard to clinical development and now lays a strong foundation for FL118 to be moved into clinical trials in the near future.

Materials and methods

Athymic nude (nu/nu) mice and severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice

Six to 12-week-old female athymic nude mice (nu/nu, body weight 20 - 25 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories International, Inc. (Wilmington, MA) or Harlan Sprague Dawley Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Six to 12-week-old female SCID mice were purchased from Roswell Park Cancer Institute Division of Laboratory Animal Resources (DLAR). Mice were housed at 5 mice per cage with water and food ad libitum. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with our Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved animal protocols.

Formulation of the anticancer agent FL118 and its mock control solution (vehicle)

FL118 formulation for i.p. administration: FL118 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to reach a concentration of 1 mg/ml, and the FL118 was further diluted into a solvent containing Tween-80 (10 - 20%) and saline (75 - 85%) to constitute the final formulated solution consisting of 0.05 mg/ml FL118, 5% DMSO (V/V), 10 - 20% Tween-80 (V/V), and 75-85% saline (V/V). Control solution (placebo or vehicle) is 5% DMSO, 10 - 20% Tween-80, and 75 - 85% saline without FL118. The formulated solution with or without FL118 was administered via i.p. injection in animal experiments with different administration schedules.

FL118 formulation for i.v. administration: The Tween 80-free formulation for i.v. administration is described in detail in our pending patent [52]. The i.v. formulation for FL118 in this study used the basic formulation recipe which contains FL118 (0.1 - 0.5 mg/ml), DMSO (5%), and hydroxypropyl-b-cyclodextrin (0.05 - 0.25%, w/v) in saline. The corresponding vehicle solution in the basic formulation recipe contains DMSO (5%) and hydroxypropyl-b-cyclodextrin (0.05 - 0.25%, w/v) in saline without FL118.

FL118 doses, schedules, and routes

FL118 in the formulated solution was administered either by i.p. injection at a dose range of 0.2 - 0.75 mg/kg, or by i.v. injection at a dose range of 1.0 - 10.0 mg/kg in different drug administration schedules. In the i.p. injection, the following schedules were used: 1) once a day for 5 days (daily x 5); 2) every other day for 3 days on days 0, 2, and 4 (q2 x 3 or i.p. x 3); 3) every other day for 5 times (q2 x 5); 4) 2 times a week for 4 weeks (2day/wk x 4). Of note, the schedule of once a week for 4 weeks (weekly x 4) via i.p. routes was evaluated in detail in our previous study [51]. In the i.v. drug administration route, the following schedules were used: 1) only one injection on day 0 (i.v. x 1); 2) daily x 5; 3) q2 x 5; and 4) weekly x 4.

Determination of the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and toxicity for FL118 in different schedules and routes

The MTD was defined as the highest drug dose at the defined drug administration schedule and route causing no drug-related lethality in mice with a body weight loss ≤ 20% of original body weight with temporary and reversible toxicities. The kinetics of drug-induced toxicities (e.g. body weight loss, mouse behavior, movement, diarrhea, and lethality) were determined daily for the first two weeks upon treatment or during drug treatment if treatment was more than two weeks. Then, drug toxicity was evaluated every other day. For FL118 formulated in the Tween 80-containing recipe in the i.p. route, we determined the FL118 MTD by starting with 0.1 mg per kg (mg/kg); we escalated doses by 0.1 – 0.25 mg/kg each time, which was dependent on the FL118 schedule, until MTD was achieved. Each dose was tested on a cohort of 5 mice in individual independent experiments. For some doses, experiments were repeated once or twice. For FL118 formulated in the Tween 80-free recipe in the i.v. route, we determined the FL118 MTD by starting with 1.0 mg/kg; we escalated doses by 0.5 – 2.5 mg/kg each time depending on FL118 schedules, until the MTD was achieved. Experiments using 3 mice were further confirmed by repeating the experiment using 5 mice.

Tumor types used in the studies

All human tumor xenografts in mouse models were established from corresponding human cancer cell lines. Tumor xenografts were initially established from human cancer cell lines by subcutaneously injecting 1 - 3 x 106 cultured cancer cells in athymic nude or SCID mice. The xenografts were then passed several generations by transplanting 30 - 50 mg non-necrotic tumor tissues via a trocar from the passaged tumors. Human tumor xenografts used in this study include human head & neck tumors established from FaDu cells, and human colon cancer tumors established from HCT-8 and SW620 cell lines. Treatment was initiated 7 days after tumor transplantation (designated as day 0) at which time the xenografted tumor sizes were about 100 - 250 mm3, depending on the initial tumor mass used for implantation. Cancer cells used for tumor establishment were tested for mycoplasma before establishment of tumors.

Tumor measurement and calculation

During treatment, tumor size was monitored and documented daily or every other day dependent on the need during the first two weeks; then, three times a week for the following two weeks of post therapy, and twice a week thereafter. Two axes (mm) of a tumor (L, longest axis; W, shortest axis) were measured with a digital vernier caliper. Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated using a formula of tumor volume (mm3) = ½ (L x W2). If a tumor mass disappeared, we maintained the experimental mice for at least 30 days after the completion of drug treatment schedules for observation of tumor relapse.

Therapeutic index definition and calculation used in this study

The definition of therapeutic index (TI) varies in the literature. The standard TI calculation in animal models usually uses the lethal dose of a drug for 50% of the population (LD50) divided by the minimum effective dose for 50% of the population (ED50). From a conservative point of view, this standard method was not chosen to calculate the FL118 TI in this study (see further discussion in the Discussion section). Instead, we used a method that is much closer to the clinical situation which does not involve animal death. The common standard TI calculated in this conservative method was defined as the MTD dose divided by the minimal dose that requires a 100% inhibition of tumor growth during the treatment period (i.e. no tumor growing larger than the tumor size on the treatment day, which is defined as day 0). In this study, a more conservative method was used; the FL118 MTD dose divided by the minimal dose that requires a 100% inhibition of tumor growth (i.e. no tumor growing larger than the tumor size on day 0) during the treatment period, plus the same length period without FL118 treatment. That is, the FL118 TI was calculated as FL118 MTD divided by the FL118 minimal effective dose defined above.

Data analysis

Data analysis and figures were made using Sigma Plot or Microsoft Excel. The mean curves of tumor changes after treatment are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) from five mice. The body weight changes upon treatment in the Tables 2 and 4 are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Table 2.

Toxicity induced by FL118 in the Tween 80-containing formulation via i.p. routes in nude and/or SCID mice

| Drug | Dose (mg/kg) | Schedule (i.p.) | Mice No* | Weight loss (%) | Lethality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL118 | 0.30 | daily x 5 | 5 | 29.0 ± 5.6 | 80 |

| FL118 | 0.20 | daily x 5 | 10 | 13.0 ± 3.7 | 0 |

| FL118 | 0.60 | q2†x 3 | 5 | 27.6 ± 13.4 | 80 |

| FL118 | 0.50 | q2†x 3 | 15 | 8.7 ± 4.9 | 0 |

| FL118 | 0.60 | q2†x 5 | 5 | 13.8 ± 3.4 | 20 |

| FL118 | 0.40 | q2†x 5 | 5 | 4.9 ± 3.5 | 0 |

| FL118 | 0.30 | q2†x 5 | 5 | 5.8 ± 5.0 | 0 |

| FL118 | 0.75 | 2 days/weekly x 3 | 5 | 27.9 ± 7.6 | 60 |

| FL118 | 0.50 | 2 days/weekly x 3 | 5 | 13.3 ± 4.3 | 0 |

Five mice were used for individual experimental groups.

Experiments where 10 mice were used, experiment repeated once, experiments where 15 mice were used, experiment repeated twice.

q2: every other day from day 0.

Table 4.

Toxicity induced by FL118 in Tween 80-free formulation via i.v. routes in nude mice*

| Drug | Dose (mg/kg) | Schedule (i.v.) | Mice No* | Weight loss (%)¥ | Lethality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL118 | 7.5 | i.v. x 1 | 5 | NP | 0 |

| FL118 | 10.0 | i.v. x 1 | 5 | NP | 0 |

| FL118 | 1.0 | daily x 5 | 5 | NP | 0 |

| FL118 | 1.5 | daily x 5 | 8 | 8.6 ± 7.8 | 0 |

| FL118 | 2.5 | daily x 5 | 3 | 22.8 ± 9.7 | 34 |

| FL118 | 1.5 | q2†x 5 | 8 | 19.8 ± 9.8 | 0 |

| FL118 | 2.5 | q2†x 5 | 8 | 19.7 ± 8.3 | 0 |

| FL118 | 3.5 | weekly x 4 | 3 | 8.1 ± 5.2 | 0 |

| FL118 | 5.0 | weekly x 4 | 8 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 0 |

| FL118 | 7.5 | weekly x 4 | 5 | NP | 80 |

Either three and/or five mice were used for individual experimental groups.

Data derived from 3 mice, and the data from the five mice were not provided by Dr. Shousong Cao.

NP: Not provided by Dr. Shousong Cao then.

q2: every other day from day 0.

Results

The MTD of FL118 in the Tween 80-free formulation is significantly increased in comparison with its MTD in the Tween 80-containing formulation

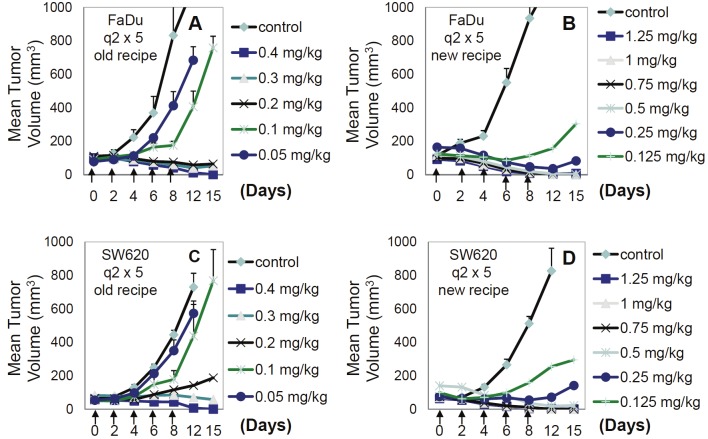

We recently reported the MTD (1.5 mg/kg) of FL118 in a Tween 80-containing formulation using a weekly x 4 schedule [51]. We now extend our studies of FL118 MTD using different drug administration schedules in animal models. Our results show that in the Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation, in contrast to 1.5 mg/kg FL118 MTD for the weekly x 4 schedule, the FL118 MTD in the daily x 5 schedule is only 0.2 mg/kg, and in the every other day for 3 doses (q2 x3) is 0.5 mg/kg. This result, together with other MTD information, is summarized in Table 1. The toxic lethal doses of FL118 in different dose comparisons are summarized in Table 2, and the lethal doses and MTD for the three schedules of daily x 5, q2 x 3, and weekly x 4 are diagramed in Figure 1.

Table 1.

The Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) of FL118 in the Tween 80-containing formulation

| Schedule | Route | Mice | MTD (mg/kg/dose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily x 5 (5 doses) | i.p. | Nude & SCID | ≤ 0.2 |

| q2† x 3 (3 doses) | i.p. | Nude | ≤ 0.5 |

| q2† x 5 (5 doses) | i.p. | SCID | ≤ 0.4 |

| 2 day/wk x 4 (8 doses) | i.p. | Nude | ≤ 0.5 |

| Weekly x 4 (4 doses)* | i.p. | Nude & SCID | ≤ 1.5 |

q2: every other day from day 0;

MTD for FL118 with the i.p. weekly x 4 schedule was previously reported (PLOS ONE. 2012, 7: e45571).

Figure 1.

Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) of FL118 in the Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation in three drug administration schedules: FL118 i.p. administration routes and schedules are indicated.

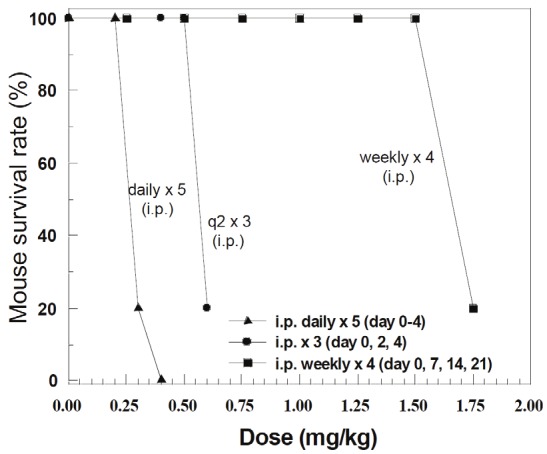

Our goal is to move FL118 into clinical trials. In this regard, the Tween 80-contraining formulation can only be used for i.p. injection, since this recipe appears to be highly toxic to animals via i.v. routes (not shown). We therefore developed a Tween 80-free formulation for FL118 i.v. administration. We then determined FL118 MTD in the Tween 80-free formulation via i.v. injection. We surprisingly found that FL118 in the new Tween 80-free formulation is much less toxic to animals and significantly increases the FL118 MTD. The MTD data from different drug administration schedules are summarized in Table 3. The lethal doses and MTD are also summarized in Table 4, and diagramed in Figure 2. As shown, the MTD for FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation increased 3-6 fold in comparison with its MTD in the Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation (Comparing data in Table 3 and Figure 2 with data in Table 1 and Figure 1). This finding suggests significant consequences in terms of potentially improving the FL118 therapeutic index (TI).

Table 3.

The Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) of FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v.-compatible new formulation

| Schedule | Route | Mice | MTD (mg/kg/dose) |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.v. x 1 (1 dose) | i.v. | SCID | ≥ 10 |

| Daily x 5 (5 doses) | i.v. | SCID | ≤ 1.5 |

| q2 x 5 (5 doses) | i.v. | SCID | ≤ 1.5 |

| Weekly x 4 (4 doses) | i.v. | SCID | ≤ 5.0 |

Figure 2.

Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) of FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation in four drug administration schedules: FL118 i.v. administration routes and schedules are indicated.

FL118 in the i.v. formulation improves antitumor efficacy and can eliminate tumors in all schedules tested

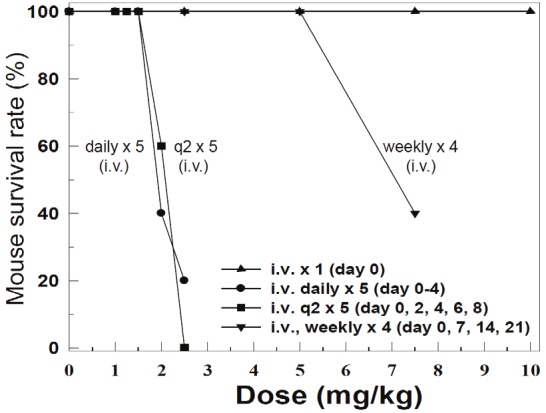

We expected that increased MTD for FL118 in the i.v. formulation should significantly improve its anticancer efficacy in comparison with the antitumor efficacy of FL118 in the Tween 80-containing formulation. Our studies indicate that FL118 in the new i.v. formulation effectively eliminates human tumor xenografts in animal models. Specifically, FL118 in the i.v. formulation was able to eliminate tumor mass in the daily x 5 schedule for both FaDu (head-&-neck) and SW620 (colon)-established tumor xenografts in animal models (Figure 3). Furthermore, FL118 in the i.v. formulation with the q2 x 5 schedule showed the best antitumor efficacy by eliminating human xenograft tumors with rare relapse in both FaDu and SW620 xenograft animal models (Figure 4). In contrast to the observation above, we found that FL118 in the i.p. formulation was unable to eliminate human FaDu and HCT-8-established tumor in the schedules of daily x 5, q2 x 3, and 2day/wk x 4 (Figure 6). Given our previous finding that FL118 in the i.p. formulation is able to eliminate xenograft tumors at its MTD (1.5 mg/kg) with weekly x 4 schedules [51], we proposed that the antitumor efficacy of FL118 in the Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation appeared to be highly schedule-dependent.

Figure 3.

Antitumor activity of FL118 in individual mice with daily x 5 schedules in human FaDu head-&-neck tumors (A-C) or SW620 colon (D-F) tumors in SCID mouse xenograft models: Tumor models were established as described in the Methods. Treatment was initiated 7 days after subcutaneous tumor implantation (designated day 0), on which tumor size was about 200 - 250 mm3. FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation was administrated via i.v. routes on day 0 at the doses and schedules shown. A and D. Control group was treated with the control solution without FL118 daily for 5 times (daily x 5). B and E. Antitumor activity of FL118 at the dose of 1.5 mg/kg with daily x 5 schedules. C and F. Antitumor activity of FL118 at the dose of 2.5 mg/kg with daily x 5 schedules.

Figure 4.

Antitumor efficacy of FL118 in individual mice with q2 x 5 schedules in human FaDu head-&-neck tumors(A, B) or SW620 colon (C, D) tumors in SCID mouse xenograft models: Tumor models are established as describedin the Methods. Treatment was initiated 7 days after subcutaneous tumor implantation (day 0), on which tumor sizewas about 200 - 250 mm3. FL118 in the Tween 80-free formulation was administrated using i.v. routes on day 0 atthe doses and schedules shown (arrowed). A and B. Anti-FaDu tumor activity of FL118 at the dose of 1.5 mg/kg and2.5 mg/kg with the schedule of every other day for five times (q2 x 5). C and D. Anti-SW620 tumor activity of FL118at the dose of 1.5 mg/kg and 2.5 mg/kg with q2 x 5 schedules.

Figure 6.

Antitumor activity and toxicity of FL118 inTween 80-containing formulation at three scheduleson FaDu (head-&-neck) and HCT-8 (colon)-derivedtumors in animal models: The tumor model is describedin the Methods. Treatment was initiated 7days (day 0) after xenograft tumor implantation atwhich tumor size was about 200 - 250 mm3. Treatmentwith different schedules is indicated within thefigures. Individual curves are the mean tumor sizeor body weight derived from five individual tumors(5 mice per group). A. The mean tumor curves derivedfrom five individual FaDu-derived tumors onfive nude mice in response to treatment with vehicle(control), or with FL118 at its corresponding MTD usingthree schedules as shown. B. The mean tumorcurves derived from five individual HCT-8-derived tumorsin response to treatment with vehicle (control),or with FL118 at its corresponding MTD using threeschedules. C. The mean mouse body weight curvesderived from five individual mice in response to treatmentwith vehicle (control), or with FL118 at its MTDusing different schedules as shown. wk: weekly. Ofnote, the standard error (SE) for tumor size and bodyweight was not provided by SC. However, based onthe data from Table 2 and our previous experiences,body weight variation is within 20% at its MTD and,tumor size variation is usually within 30%.

Together, it appears that the i.v.-compatible formulation of FL118 expanded its schedule scope, and improved antitumor efficacy, especially in the daily x 5 and q2 x 5 schedules (Figures 3, 4). Interestingly, the q2 x 5 became the best schedule for FL118 in the i.v. formulation among three major clinically compatible drug i.v. administration schedules (daily x 5, q2 x 5, weekly x 5). Importantly, FL118 in the Tween 80-free formulation is compatible with both i.v. (a common route in the clinic) and i.p. (a rare route in the clinic) administration of FL118. Thus, the i.v.-compatible formulation would facilitate the efforts to move FL118 into clinical trials.

FL118 in the i.v. formulation significantly increases its therapeutic index (TI) in comparison with those of FL118 in the i.p. formulation

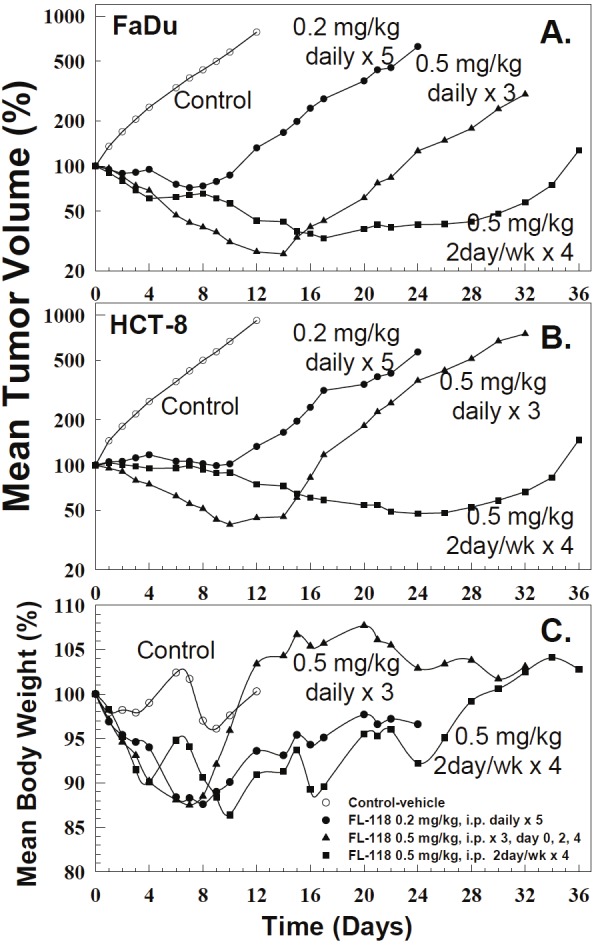

To alternatively confirm the findings shown in Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6, we expanded the dose range with 5 mice per group for individual dose points, and determined the TI for FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation against FL118 in the Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation. Here, we chose the q2 x 5 schedule because it is the most effective schedule among three major schedules tested in this study (Figures 3, 4 and 5). We determined FL118 antitumor efficacy in various sub-MTD doses from both formulations. Since FL118 in the Tween 80-containing formulation could only be injected via i.p. (too toxic for i.v. injection), we therefore chose to use the i.p. route for antitumor efficacy comparison in a series of defined FL118 doses in the experiment. Our studies revealed that for the human FaDu head-&-neck tumors, the minimal dose of FL118 that is required for a 100% inhibition of tumor growth (no growth in comparison with the tumor size on day 0) is 0.2 mg/kg in the i.p. formulation (Figure 7A) and is 0.25 mg/kg in the i.v. formulation (Figure 7B); for the human SW620 colon tumor, the minimal dose of FL118 is 0.3 mg/kg in the i.p. formulation (Figure 7C) and is between 0.25 mg/kg and 0.5 mg/kg in the i.v. formulation (Figure 7D). Based on the formula of TI = MTD/minimal effective dose, the FL118 TI in the i.p. formulation for the FaDu tumor will be 0.4/0.2 (TI = 2); and the FL118 TI in the i.v. formulation is 1.5/0.25 (TI = 6). Similarly, the TI of FL118 in the i.v. formulation is 0.4/0.3 (TI = 1.3) for the SW620 tumor; and the TI of FL118 in the i.v. formulation would be 1.5/0.3 (TI = 5) for the SW620 tumor. In short, the range of FL118 TI in the defined two types of tumor in the Tween 80 containing formulation is 1.3 – 2.0. In contrast, the range of FL118 TI in the same tumor types in the Tween 80-free formulation is 5.0 – 6.0. This would greatly improve the safety for FL118 administration in animal and/or humans.

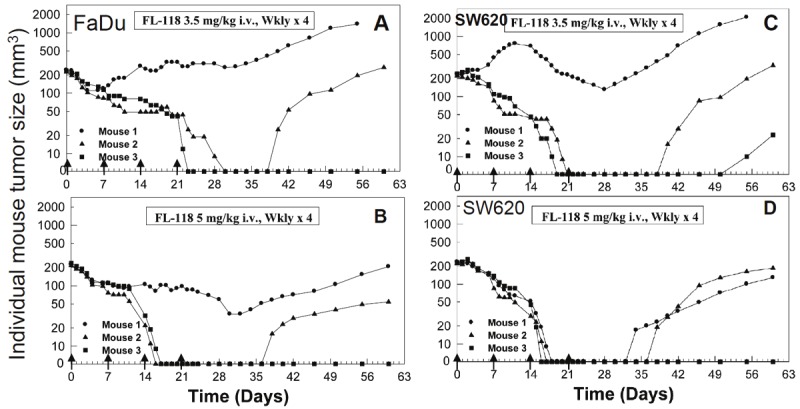

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of FL118 in individual mice with weekly x 4 schedules in human FaDu head-&-neck tumors (A, B) or SW620 colon (C, D) tumors in SCID mouse xenograft models: The tumor model is described in the Methods. Treatment was initiated 7 days after subcutaneous tumor implantation (day 0), on which tumor size was about 200 - 250 mm3. FL118 in Tween 80-free formulation was administrated using i.v. routes on day 0 at the doses and schedules shown (arrowed). A and B. Anti-FaDu tumor activity of FL118 at the dose of 3.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg with weekly x 4 schedules. C and D. Anti-SW620 tumor activity of FL118 at the dose of 3.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg with weekly x 4. wkly: weekly.

Figure 7.

Determination of therapeutic index (TI) of FL118 in both Tween 80-containing i.p. formulations and Tween80-free i.v. formulations: Tumor models were established as described in the Methods. Treatment was initiated 7days after subcutaneous tumor implantation (day 0), at which tumor size was about 100 - 200 mm3. FL118 eitherin the Tween 80-containing (A, C) or Tween 80-free (B, D) formulation was administrated through i.p. routes on day0 at a series of the corresponding sub-MTD doses and schedules as shown. Each curve is the mean ± SE derivedfrom five individual tumors (5 mice per group). Representative SE were shown.

Discussion

It has been shown that abrogation of one or more of these four gene products, survivin, Mcl-1, XIAP and cIAP2, inhibits tumor growth, sensitizes drug resistant cancer cells to treatment, and induces apoptosis in various in vitro and in vivo models [53-61], although which one or more of these gene products is playing critical roles in these events may be cancer cell type specific. A great deal of chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agents were reported to inhibit survivin expression as one of their mechanisms of action [62]. Among these agents, YM155 is very interesting and was shown to be a survivin expression suppressant that shows antitumor activity [63-65]. YM155 was also shown to sensitize cells to radiotherapy [66] or chemotherapy [67,68] in preclinical animal models. YM155 is currently in Phase I/II clinical trials [69-72]. However, based on the outcome from Phase II studies, only modest activity was observed [62,70,72-74]. Nevertheless, we have shown that YM155-mediated abrogation of Sp1 binding on the survivin promoter at -149 to -71 plays a role in its survivin transcription inhibition [75]. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that YM155 and its analog, NSC80467, appear to be DNA damaging antitumor agents, and suppression of survivin transcription could be a secondary event [76].

It is clear that development of additional small chemical molecule survivin inhibitors with high antitumor efficacy and low toxicity are still highly desirable for the treatment of cancer. However, survivin is a multifunctional molecule with unique multi-subcellular localizations in cancer cells. Survivin has been shown to associate with both mitotic spindles [77] and centromeres [78,79] during mitosis, [80] as well as on mitochondria [81]. Its expression is involved in inhibition of apoptosis, [77,81] and regulation of mitotic cell division, [78,79,82,83] as well as in promotion of the G1/S transition, [84-86] and regulation of gene transcription [86,87]. Thus, development of versatile survivin functional inhibitors may technically be more challenging than to develop survivin expression inhibitors. Our research group recently reported the discovery of a novel anticancer small chemical molecule, FL118, which was shown to selectively inhibit the expression of not only survivin, but also Mcl-1, XIAP, and cIAP2 with striking antitumor activity in the schedule of weekly x 4 in animal models [51]. While this is an important discovery, we still have challenges that need to be solved before we can move FL118 into clinical trials. One of our challenges is that although Tween 80 (polysorbate 80) is a FDA-acceptable solvent for drug formulation, 10 - 20% Tween 80 in the finally formulated solution is clearly too high a concentration for clinical application. Therefore, improvement of the current formulation for FL118 by decreasing the percentage of Tween 80 or replacing it with other more acceptable solvents might result in a favorable potential for FL118 to further decrease drug toxicity and increase drug MTD, and thus, improveFL118 antitumor efficacy and TI.

In this context, we have developed a Tween 80-free formulation for FL118 which is compatible with both i.v. and i.p. administration routes of the drug. Specifically, we had tried many solvent combinations in various concentrations and finally found that the cyclodextrin-based formulation, with or without a low percentage of other solvents (PG, PEG 300 or PEG 400), worked fine with FL118 [52]. In the present study, we used the basic Tween 80-free formulation containing hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin without other solvents (refer to Methods section), which is the simplest recipe that can be used for i.v. injection of FL118. As we showed in this study, we surprisingly found that FL118 in this Tween 80-free new formulation exhibited much lower toxicity, and thus, significantly increased FL118 MTD in various drug administration schedules (see the data shown in Figure 2 and Table 3 versus Figure 1 and Table 1). This is a breakthrough finding because FL118 in the i.v. formulation showed outstanding antitumor activity in various drug administration schedules (Figures 3, 4 and 5). This is in striking contrast to the antitumor outcome resulted from FL118 in the Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation (Figure 6). Nevertheless, we observed an interesting phenomenon that while FL118 in the Tween 80-free formulation shows very low toxicity to animals when delivered through i.v. routes, FL118 in this i.v. formulation showed a higher toxicity when injected through i.p. routes. In contrast, the i.p. route is the only route for FL118 in the Tween 80-containing formulation to be administrated, since the Tween 80 formulation solution itself was shown to be highly toxic when injected via the i.v. route. This phenomenon may not be significant in terms of FL118 in the Tween 80-free formulation which results in superior antitumor activity and low toxicity when injected via the i.v. route, since the i.v. route is the clinically compatible route for most anticancer drug delivery in hospitalized cancer patients with ovarian cancer patients the exception.

Previous studies have shown that mice-derived tumors with the exact same genetic background exhibit much different topotecan resistant behavior (i.e. some tumors show very sensitive, but others show very resistant responses to topotecan from the beginning), when the isolated tumors were sub-implanted on 20 individual mice and treated with topotecan [88]. Consistent with this phenomenon, we found that in some cases, the variation of tumor inhibition by FL118 could be significantly different among individual mice (i.e., Data in Figure 5). However, in most cases, the variation is within a reasonable range as shown in Figures 6 and 7. Of note, in Figures 6 and 7, we show some typical examples of the variation derived from five mice. Alternatively, the data from individual mice were shown for the readers to observe the real variation of tumor after FL118 treatment with various schedules (Figures 3, 4 and 5).

It is known that the antitumor efficacy of a drug at its sub-MTD level is a foundation and gold standard for predicting the potential of a drug for its further development toward clinical application. This gold standard decides TI levels, which reflect the anticancer drug potential. Therefore, in the present study, we have compared in detail the TI of FL118 in the i.v. formulation versus FL118 in the i.p. formulation (Figure 7). We found that the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation decreases FL118 toxicity, and increases its MTD and anticancer efficacy (compare Figures 3, 4 and 5 with Figure 6). Given the two types of human tumors used, the TI of FL118 in the Tween 80-free i.v. formulation is 5-6, but only 1.3-2 in the old Tween 80-containing i.p. formulation. We noted that the standard TI calculated in animal models usually uses the lethal dose of a drug for 50% of the population (LD50) divided by the minimum effective dose for 50% of the population (ED50) as mentioned in the Methods section. We did not choose this method to calculate TI for at least two reasons. First, different definitions of the minimum ED50 would derive much different TI. Second, using LD50 is less safe than using MTD in our view, since LD50 involves animal death, while using MTD, animal death would not be involved. In this regard, the FL118 TI derived in this study is a conservative number. It is possible that using other calculation methods may derive a much higher TI value. Furthermore, in clinical trials, toxicity in 50% of the population (TD50), rather than LD50, should be used. Therefore, the calculation method used in this study appears to be much closer to the situation used in clinical trials, since animal death was not involved for the calculation of FL118 TI in this study. We understand that since FL118 is highly effective to inhibit human tumor growth, we were able to get a very favorable TI number using our conservative calculation method. In the case of if a drug could only delay tumor growth rates during treatment period, the TI calculation method used in this study may not fit those types of drugs, since if using our defined method to calculate TI, the TI for such types of drugs will be smaller than 1, which would not lead to further development. In the case of such type of drugs, the LD50/ED50 may be a better choice for calculating the TI. Finally, we should mention that in order to have a comparison in the same condition during TI determination studies, and because i.p. formulation could not be used for i.v. administration, we chose i.p. routes to compare the antitumor efficacy of FL118 in i.v. formulation versus i.p. formulation (Figure 7). We expect that if FL118 in the i.v. formulation was delivered through i.v. administration, the TI could be even better. Nevertheless a TI at 5-6 is already high enough for safe delivery of the drug in vivo.

An additional interesting observation is that our previous studies demonstrated that FL118 at its MTD is able to eliminate human primary head-and-neck tumors in the schedule of weekly x 4 via the i.p. route [51]. However our present studies demonstrated that FL118 in the new formulation at either sub-MTD or MTD is unable to 100% eliminate FaDu-established head-&-neck tumors in the schedule of weekly x 5 (Figure 5). Whether this suggests that FL118 may be more effective for head-&-neck cancer directly from cancer patients than those from cancer cell line-derived tumors would be an intriguing question worthy of further investigation. If the future studies would derive positive results, the potential and the value of FL118 for clinical application to treat cancer patients would be further increased.

In summary, given the unique feature and new findings for FL118 shown in this study, plus the findings presented in our previous studies [51], it is clear that FL118 is a highly promising and potential anticancer agent. The findings described in this report overcome several challenges (e.g. FL118 formulation, clinically compatible route, expanded schedules and improved TI) on the way to moving FL118 toward clinical trials and beyond.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored in part by grants from the US Army Department of Defense (DOD, PC110408), Mesothelioma Applied Research Foundation (Alexandria, VA), and the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation to FL, and by shared resources supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant to Roswell Park Cancer Institute (CA016056). Of note, SC was partially paid by grants from FL during this work. We thank Dr. Shousong Cao (SC) for his help in some of animal experiments in this work. The authors would like to thank the Faculty Writing Group from the Pharmacology & Therapeutics Department of Roswell Park Cancer Institute for critically reading and commenting on this manuscript. These authors would also like to thank Dr. Suzanne M. Hess (Research Support Services, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo NY) for critically reading and revising this manuscript. Finally, we would like to thank the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, Developmental Therapeutics Program (DTP), Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute (NCI) for providing chemical libraries and relevant hit analogs in the public domain they collected and/or synthesized as major compound sources during the process of drug screening and characterization.

Conflict of interest

FL118 will be further developed in Canget BioTekpharma LLC (www.canget-biotek.com), a Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) spinoff company. FL is the founder of Canget BioTekpharma. Otherwise, there is no other conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Altieri DC. Survivin, cancer networks and pathway-directed drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altieri DC. Survivin and IAP proteins in cell-death mechanisms. Biochem J. 2010;430:199–205. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li F, Ling X. Survivin Study: An update of “What is the next wave?”. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:476–486. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodel F, Hoffmann J, Distel L, Herrmann M, Noisternig T, Papadopoulos T, Sauer R, Rodel C. Survivin as a radioresistance factor, and prognostic and therapeutic target for radiotherapy in rectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4881–4887. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter BZ, Mak D, Schober WD, Cabreira-Hansen M, Beran M, McQueen T, Chen W, Andreeff M. Regulation of survivin expression through Bcr-Abl/MAPK cascade: Targeting survivin overcomes Imatinib resistance and increases Imatinib sensitivity in Imatinib responsive CML cells. Blood. 2006;107:1555–1563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peng X, Karna P, Cao Z, Jiang B, Zhou M, Yang L. Cross-talk between epidermal growth factor receptor and HIF-1 signal pathways increases resistance to apoptosis by upregulating survivin gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25903–25914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603414200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J, Apontes P, Song L, Liang P, Yang L, Li F. Molecular mechanism of upregulation of survivin transcription by the AT-rich DNA-binding ligand, Hoechst33342: evidence for survivin involvement in drug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2390–2402. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh SH, Jin Q, Kim ES, Khuri FR, Lee HY. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling pathway induces resistance to the apoptotic activities of SCH66336 (lonafarnib) through Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated increases in survivin expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1581–1589. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Ling X, Pan D, Apontes P, Song L, Liang P, Altieri DC, Beerman T, Li F. Molecular mechanism of inhibition of survivin transcription by the GC-rich sequence selective DNA-binding antitumor agent, hedamycin: evidence of survivin downregulation associated with drug sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9745–9751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409350200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fetz V, Bier C, Habtemichael N, Schuon R, Schweitzer A, Kunkel M, Engels K, Kovacs AF, Schneider S, Mann W, Stauber RH, Knauer SK. Inducible NO synthase confers chemoresistance in head and neck cancer by modulating survivin. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2033–2041. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gritsko T, Williams A, Turkson J, Kaneko S, Bowman T, Huang M, Nam S, Eweis I, Diaz N, Sullivan D, Yoder S, Enkemann S, Eschrich S, Lee JH, Beam CA, Cheng J, Minton S, Muro-Cacho CA, Jove R. Persistent Activation of Stat3 Signaling Induces Survivin Gene Expression and Confers Resistance to Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:11–19. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moriai R, Tsuji N, Moriai M, Kobayashi D, Watanabe N. Survivin plays as a resistant factor against tamoxifen-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;117:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu J, Tan M, Huang WC, Li P, Guo H, Tseng LM, Su XH, Yang WT, Treekitkarnmongkol W, Andreeff M, Symmans F, Yu D. Mitotic deregulation by survivin in ErbB2-overexpressing breast cancer cells contributes to Taxol resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1326–1334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang M, Latham DE, Delaney MA, Chakravarti A. Survivin mediates resistance to antiandrogen therapy in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:2474–2482. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo J, Lee YJ. Aspirin enhances tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells through survivin downregulation. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1586–1592. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roca H, Varsos Z, Pienta KJ. CCL2 protects prostate cancer PC3 cells from autophagic death via PI3K/AKT-dependent survivin upregulation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25057–25073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801073200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman KM, Banerjee S, Ali S, Ahmad A, Wang Z, Kong D, Sakr WA. 3,3’-Diindolylmethane enhances taxotere-induced apoptosis in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells through survivin down-regulation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4468–4475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S, Huang X, Lee CK, Liu B. Elevated expression of erbB3 confers paclitaxel resistance in erbB2-overexpressing breast cancer cells via upregulation of Survivin. Oncogene. 2010;29:4225–4236. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park E, Gang EJ, Hsieh YT, Schaefer P, Chae S, Klemm L, Huantes S, Loh M, Conway EM, Kang ES, Koo HH, Hofmann WK, Heisterkamp N, Pelus L, Keerthivasan G, Crispino J, Kahn M, Muschen M, Kim YM. Targeting survivin overcomes drug resistance in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:2191–2199. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-351239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okamoto K, Okamoto I, Hatashita E, Kuwata K, Yamaguchi H, Kita A, Yamanaka K, Ono M, Nakagawa K. Overcoming Erlotinib Resistance in EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells by Targeting Survivin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:204–213. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon MJ, Park SS, Kang YJ, Kim IY, Lee JA, Lee JS, Kim EG, Lee CW, Choi KS. Aurora B confers cancer cell resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via phosphorylation of survivin. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:492–500. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taniai M, Grambihler A, Higuchi H, Werneburg N, Bronk SF, Farrugia DJ, Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ. Mcl-1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3517–3524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song L, Coppola D, Livingston S, Cress D, Haura EB. Mcl-1 regulates survival and sensitivity to diverse apoptotic stimuli in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:267–276. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.3.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wirth T, Kuhnel F, Fleischmann-Mundt B, Woller N, Djojosubroto M, Rudolph KL, Manns M, Zender L, Kubicka S. Telomerase-dependent virotherapy overcomes resistance of hepatocellular carcinomas against chemotherapy and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand by elimination of Mcl-1. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7393–7402. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin X, Morgan-Lappe S, Huang X, Li L, Zakula DM, Vernetti LA, Fesik SW, Shen Y. ‘Seed’ analysis of off-target siRNAs reveals an essential role of Mcl-1 in resistance to the small-molecule Bcl-2/Bcl-XL inhibitor ABT-737. Oncogene. 2007;26:3972–3979. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen M, Marcellus RC, Roulston A, Watson M, Serfass L, Murthy Madiraju SR, Goulet D, Viallet J, Belec L, Billot X, Acoca S, Purisima E, Wiegmans A, Cluse L, Johnstone RW, Beauparlant P, Shore GC. Small molecule obatoclax (GX15-070) antagonizes MCL-1 and overcomes MCL-1-mediated resistance to apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19512–19517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709443104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci MS, Kim SH, Ogi K, Plastaras JP, Ling J, Wang W, Jin Z, Liu YY, Dicker DT, Chiao PJ, Flaherty KT, Smith CD, El-Deiry WS. Reduction of TRAIL-induced Mcl-1 and cIAP2 by c-Myc or sorafenib sensitizes resistant human cancer cells to TRAIL-induced death. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chetoui N, Sylla K, Gagnon-Houde JV, Alcaide-Loridan C, Charron D, Al-Daccak R, Aoudjit F. Down-regulation of mcl-1 by small interfering RNA sensitizes resistant melanoma cells to fas-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:42–52. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boisvert-Adamo K, Longmate W, Abel EV, Aplin AE. Mcl-1 is required for melanoma cell resistance to anoikis. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:549–556. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hauck P, Chao BH, Litz J, Krystal GW. Alterations in the Noxa/Mcl-1 axis determine sensitivity of small cell lung cancer to the BH3 mimetic ABT-737. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:883–892. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin AP, Mitchell C, Rahmani M, Nephew KP, Grant S, Dent P. Inhibition of MCL-1 enhances lapatinib toxicity and overcomes lapatinib resistance via BAK-dependent autophagy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:2084–2096. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.21.9895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simonin K, Brotin E, Dufort S, Dutoit S, Goux D, N’Diaye M, Denoyelle C, Gauduchon P, Poulain L. Mcl-1 is an important determinant of the apoptotic response to the BH3-mimetic molecule HA14-1 in cisplatin-resistant ovarian carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:3162–3170. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stam RW, Den Boer ML, Schneider P, de Boer J, Hagelstein J, Valsecchi MG, de Lorenzo P, Sallan SE, Brady HJ, Armstrong SA, Pieters R. Association of high-level MCL-1 expression with in vitro and in vivo prednisone resistance in MLL-rearranged infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:1018–1025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li QF, Yan J, Zhang K, Yang YF, Xiao FJ, Wu CT, Wang H, Wang LS. Bortezomib and sphingosine kinase inhibitor interact synergistically to induces apoptosis in BCR/ABl+ cells sensitive and resistant to STI571 through down-regulation Mcl-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tromp JM, Geest CR, Breij EC, Elias JA, van Laar J, Luijks DM, Kater AP, Beaumont T, Van Oers MH, Eldering E. Tipping the Noxa/Mcl-1 balance overcomes ABT-737 resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;18:487–98. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holcik M, Yeh C, Korneluk RG, Chow T. Translational upregulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) increases resistance to radiation induced cell death. Oncogene. 2000;19:4174–4177. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Li Y, Shen B. Up-regulation of XIAP by M-CSF is associated with resistance of myeloid leukemia cells to apoptosis. Leukemia. 2002;16:2163–2165. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amantana A, London CA, Iversen PL, Devi GR. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein inhibition induces apoptosis and enhances chemotherapy sensitivity in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:699–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin MT, Chang CC, Chen ST, Chang HL, Su JL, Chau YP, Kuo ML. Cyr61 expression confers resistance to apoptosis in breast cancer MCF-7 cells by a mechanism of NF-kappaB-dependent XIAP up-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24015–24023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berezovskaya O, Schimmer AD, Glinskii AB, Pinilla C, Hoffman RM, Reed JC, Glinsky GV. Increased expression of apoptosis inhibitor protein XIAP contributes to anoikis resistance of circulating human prostate cancer metastasis precursor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2378–2386. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tong QS, Zheng LD, Wang L, Zeng FQ, Chen FM, Dong JH, Lu GC. Downregulation of XIAP expression induces apoptosis and enhances chemotherapeutic sensitivity in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12:509–514. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braeuer SJ, Buneker C, Mohr A, Zwacka RM. Constitutively activated nuclear factor-kappaB, but not induced NF-kappaB, leads to TRAIL resistance by up-regulation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein in human cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:715–728. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrader M, Pino MS, Lashinger L, Bar-Eli M, Adam L, Dinney CP, McConkey DJ. Gefitinib reverses TRAIL resistance in human bladder cancer cell lines via inhibition of AKT-mediated X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein expression. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1430–1435. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogler M, Walczak H, Stadel D, Haas TL, Genze F, Jovanovic M, Gschwend JE, Simmet T, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Targeting XIAP bypasses Bcl-2-mediated resistance to TRAIL and cooperates with TRAIL to suppress pancreatic cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7956–7965. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aird KM, Ghanayem RB, Peplinski S, Lyerly HK, Devi GR. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein inhibits apoptosis in inflammatory breast cancer cells with acquired resistance to an ErbB1/2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1432–1442. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan H, Fu F, Zhuo J, Wang W, Nishitani J, An DS, Chen IS, Liu X. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins upregulate cIAP2 gene expression and confer resistance to apoptosis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5069–5078. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karasawa H, Miura K, Fujibuchi W, Ishida K, Kaneko N, Kinouchi M, Okabe M, Ando T, Murata Y, Sasaki H, Takami K, Yamamura A, Shibata C, Sasaki I. Down-regulation of cIAP2 enhances 5-FU sensitivity through the apoptotic pathway in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:903–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersen SL, Peyton M, Minna JD, Wang X. Overcoming cancer cell resistance to Smac mimetic induced apoptosis by modulating cIAP-2 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11936–11941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005667107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu HH, Wu JY, Cheng YW, Chen CY, Lee MC, Goan YG, Lee H. cIAP2 upregulated by E6 oncoprotein via epidermal growth factor receptor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway confers resistance to cisplatin in human papillomavirus 16/18-infected lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:5200–5210. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagata M, Nakayama H, Tanaka T, Yoshida R, Yoshitake Y, Fukuma D, Kawahara K, Nakagawa Y, Ota K, Hiraki A, Shinohara M. Overexpression of cIAP2 contributes to 5-FU resistance and a poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1322–1330. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling X, Cao S, Cheng Q, Keefe JT, Rustum YM, Li F. A Novel Small Molecule FL118 That Selectively Inhibits Survivin, Mcl-1, XIAP and cIAP2 in a p53-Independent Manner, Shows Superior Antitumor Activity. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e45571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li F, Ling X, Cao S, inventors. Novel Formulations of Water-Insoluble Chemical Compounds and Methods of Using a Formulation of Compound FL118 for Cancer Therapy. Roswell Park Cancer Institute at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) 2011 non-provisional patent in pending, PCT/US11/58558.

- 53.Ruckert F, Samm N, Lehner AK, Saeger HD, Grutzmann R, Pilarsky C. Simultaneous gene silencing of Bcl-2, XIAP and Survivin resensitizes pancreatic cancer cells towards apoptosis. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:379. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Montazeri Aliabadi H, Landry B, Mahdipoor P, Uludag H. Induction of Apoptosis by Survivin Silencing through siRNA Delivery in a Human Breast Cancer Cell Line. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:1821–1830. doi: 10.1021/mp200176v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chu ZL, McKinsey TA, Liu L, Gentry JJ, Malim MH, Ballard DW. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death by inhibitor of apoptosis c-IAP2 is under NF-kappaB control. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Sep 16;94:10057–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhattacharya S, Ray RM, Johnson LR. STAT3-mediated transcription of Bcl-2, Mcl-1 and c-IAP2 prevents apoptosis in polyamine-depleted cells. Biochem J. 2005;392:335–344. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Friboulet L, Pioche-Durieu C, Rodriguez S, Valent A, Souquere S, Ripoche H, Khabir A, Tsao SW, Bosq J, Lo KW, Busson P. Recurrent overexpression of c-IAP2 in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinomas: critical role in resistance to Toll-like receptor 3-mediated apoptosis. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1183–1194. doi: 10.1593/neo.08590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jang BC, Paik JH, Jeong HY, Oh HJ, Park JW, Kwon TK, Song DK, Park JG, Kim SP, Bae JH, Mun KC, Suh MH, Yoshida M, Suh SI. Leptomycin B-induced apoptosis is mediated through caspase activation and down-regulation of Mcl-1 and XIAP expression, but not through the generation of ROS in U937 leukemia cells. Biochem pharmacol. 2004;68:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee TJ, Jung EM, Lee JT, Kim S, Park JW, Choi KS, Kwon TK. Mithramycin A sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis by down-regulation of XIAP gene promoter through Sp1 sites. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2737–2746. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hussain SR, Cheney CM, Johnson AJ, Lin TS, Grever MR, Caligiuri MA, Lucas DM, Byrd JC. Mcl-1 is a relevant therapeutic target in acute and chronic lymphoid malignancies: down-regulation enhances rituximab-mediated apoptosis and complement-dependent cytotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2007 Apr 1;13:2144–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chetoui N, Sylla K, Gagnon-Houde JV, Alcaide-Loridan C, Charron D, Al-Daccak R, Aoudjit F. Down-regulation of mcl-1 by small interfering RNA sensitizes resistant melanoma cells to fas-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2008 Jan;6:42–52. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li F. Discovery of Survivin Inhibitors and Beyond: FL118 as a Proof of Concept. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2013:305. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407695-2.00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakahara T, Takeuchi M, Kinoyama I, Minematsu T, Shirasuna K, Matsuhisa A, Kita A, Tominaga F, Yamanaka K, Kudoh M, Sasamata M. YM155, a novel small-molecule survivin suppressant, induces regression of established human hormone-refractory prostate tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8014–8021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakahara T, Kita A, Yamanaka K, Mori M, Amino N, Takeuchi M, Tominaga F, Kinoyama I, Matsuhisa A, Kudou M, Sasamata M. Broad spectrum and potent antitumor activities of YM155, a novel small-molecule survivin suppressant, in a wide variety of human cancer cell lines and xenograft models. Cancer Sci. 2010;102:614–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kita A, Nakahara T, Yamanaka K, Nakano K, Nakata M, Mori M, Kaneko N, Koutoku H, Izumisawa N, Sasamata M. Antitumor effects of YM155, a novel survivin suppressant, against human aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2011;35:787–792. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iwasa T, Okamoto I, Suzuki M, Nakahara T, Yamanaka K, Hatashita E, Yamada Y, Fukuoka M, Ono K, Nakagawa K. Radiosensitizing effect of YM155, a novel small-molecule survivin suppressant, in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6496–6504. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Iwasa T, Okamoto I, Takezawa K, Yamanaka K, Nakahara T, Kita A, Koutoku H, Sasamata M, Hatashita E, Yamada Y, Kuwata K, Fukuoka M, Nakagawa K. Marked anti-tumour activity of the combination of YM155, a novel survivin suppressant, and platinum-based drugs. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakahara T, Yamanaka K, Hatakeyama S, Kita A, Takeuchi M, Kinoyama I, Matsuhisa A, Nakano K, Shishido T, Koutoku H, Sasamata M. YM155, a novel survivin suppressant, enhances taxane-induced apoptosis and tumor regression in a human Calu 6 lung cancer xenograft model. Anticancer Drugs. 2011;22:454–462. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328344ac68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tolcher AW, Mita A, Lewis LD, Garrett CR, Till E, Daud AI, Patnaik A, Papadopoulos K, Takimoto C, Bartels P, Keating A, Antonia S. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of YM155, a Small-Molecule Inhibitor of Survivin. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5198–5203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lewis KD, Samlowski W, Ward J, Catlett J, Cranmer L, Kirkwood J, Lawson D, Whitman E, Gonzalez R. A multi-center phase II evaluation of the small molecule survivin suppressor YM155 in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:161–166. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Satoh T, Okamoto I, Miyazaki M, Morinaga R, Tsuya A, Hasegawa Y, Terashima M, Ueda S, Fukuoka M, Ariyoshi Y, Saito T, Masuda N, Watanabe H, Taguchi T, Kakihara T, Aoyama Y, Hashimoto Y, Nakagawa K. Phase I study of YM155, a novel survivin suppressant, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3872–3880. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tolcher AW, Quinn DI, Ferrari A, Ahmann F, Giaccone G, Drake T, Keating A, de Bono JS. A phase II study of YM155, a novel small-molecule suppressor of survivin, in castration-resistant taxane-pretreated prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;23:968–973. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giaccone G, Zatloukal P, Roubec J, Floor K, Musil J, Kuta M, van Klaveren RJ, Chaudhary S, Gunther A, Shamsili S. Multicenter phase II trial of YM155, a small-molecule suppressor of survivin, in patients with advanced, refractory, non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:4481–4486. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheson BD, Bartlett NL, Vose JM, Lopez-Hernandez A, Seiz AL, Keating AT, Shamsili S. A phase II study of the survivin suppressant YM155 in patients with refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3128–3134. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng Q, Ling X, Haller A, Nakahara T, Yamanaka K, Kita A, Koutoku H, Takeuchi M, Brattain MG, Li F. Suppression of survivin promoter activity by YM155 involves disruption of Sp1-DNA interaction in the survivin core promoter. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:179–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glaros TG, Stockwin LH, Mullendore ME, Smith B, Morrison BL, Newton DL. The “survivin suppressants” NSC 80467 and YM155 induce a DNA damage response. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012 Jul;70:207–12. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1868-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu EY, Plescia J, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Control of apoptosis and mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature. 1998;396:580–584. doi: 10.1038/25141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skoufias DA, Mollinari C, Lacroix FB, Margolis RL. Human survivin is a kinetochore-associated passenger protein. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1575–1582. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uren AG, Wong L, Pakusch M, Fowler KJ, Burrows FJ, Vaux DL, Choo KH. Survivin and the inner centromere protein INCENP show similar cell-cycle localization and gene knockout phenotype. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1319–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li F. Survivin Study: What is the next wave? J Cell Physiol. 2003;197:8–29. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dohi T, Beltrami E, Wall NR, Plescia J, Altieri DC. Mitochondrial survivin inhibits apoptosis and promotes tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1117–1127. doi: 10.1172/JCI22222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li F, Ackermann EJ, Bennett CF, Rothermel AL, Plescia J, Tognin S, Villa A, Marchisio PC, Altieri DC. Pleiotropic cell-division defects and apoptosis induced by interference with survivin function. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:461–466. doi: 10.1038/70242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reed JC, Reed SI. Survivin’ cell-separation anxiety. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E199–200. doi: 10.1038/70227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li F, Brattain MG. Role of the Survivin Gene in Pathophysiology. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1–11. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li F, Ling X, Huang H, Brattain L, Apontes P, Wu J, Binderup L, Brattain MG. Differential regulation of survivin expression and apoptosis by vitamin D(3) compounds in two isogenic MCF-7 breast cancer cell sublines. Oncogene. 2005;24:1385–1395. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tang L, Ling X, Liu W, Das GM, Li F. Transcriptional inhibition of p21(WAF1/CIP1) gene (CDKN1) expression by survivin is at least partially p53-dependent: Evidence for survivin acting as a transcription factor or co-factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 May 4;421:249–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang M, Yang J, Li F. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional controls of survivin in cancer cells: novel approaches for cancer treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2006;25:391–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zander SA, Kersbergen A, van der Burg E, de Water N, van Tellingen O, Gunnarsdottir S, Jaspers JE, Pajic M, Nygren AO, Jonkers J, Borst P, Rottenberg S. Sensitivity and acquired resistance of BRCA1; p53-deficient mouse mammary tumors to the topoisomerase I inhibitor topotecan. Cancer Res. 2010 Feb 15;70:1700–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]