INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BP) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are among the most severe, persistent, and debilitating illnesses occurring in young people, with an estimated lifetime prevalence of approximately 1-1.5% for BP (Kessler et al., 2005; Kato, 2007; Merikangas et al. 2007; Braff and Freedman, 2008) and 9.2–19.6% for MDD (Kessler et al., 2005; Vicente et al. 2006; Kao et al. 2011). Although genetic testing for psychiatric disorders has been the goal of psychiatrists and geneticists for years (Braff and Freedman, 2008) this goal has been difficult to attain since the impact of individual genes on risk for psychiatric illness is small, often nonspecific and embedded in intricate causal pathways (Kendler, 2005). In contrast to Mendelian disorders, tests for complex conditions such as MDD and BP may yield only weak estimates of risk, as such conditions appear to be caused by a complicated interplay of multiple genetic and environmental factors, and the associated genetic variants may be common and confer only a small increment of increased or decreased risk (Wright and Kroese, 2010).

Major depressive disorder and BP clearly have an important genetic component (Trippitelli et al. 1998; Bienvenu et al., 2010), yet results from genetic testing research have been largely confusing and contradictory (Jordan and Tsai, 2010). However, recent progress in the identification of millions of genetic markers and in powerful detection technologies has made it feasible to perform large-scale association analyses that have enough statistical power to identify genes exerting a relatively minor effect on the likelihood of a particular ailment (Bienvenu et al., 2010; Jordan and Tsai, 2010). In the current DNA-centered mindset, genetic tests are often seen as the first step towards new therapies, and many patient groups are lobbying for their development in the belief that such testing can be helpful in selecting the best treatment (as may occasionally be the case) or in reassuring anxious parents (Jordan and Tsai, 2010). Companies involved in molecular diagnostics, a $20 billion market in the United States, strive to develop diagnostic kits and systems, (Jordan and Tsai, 2010). Tests claiming to indicate increased genetic risks for BP and antidepressant response are already available commercially from companies, such as 23andMe.

Great hopes are attached to psychiatric genetics with the goal of both better treatment and prevention and the anticipated de-stigmatizing effect of attributing mental illness to biological causes (Smits et al., 2007; Braff and Freedman, 2008; Couzin, 2008; Laegsgaard et al., 2009; Hoop et al., 2010; Facio et al., 2011). For carriers of variants that influence risk, genetic testing provides the potential to improve outcomes through prevention, early detection, tailored medication, and a better-quality basis for making reproductive decisions (Meiser et al., 2008). Studies have found positive attitudes towards predictive genetic testing for predisposition to psychiatric disorders among various stakeholders. These stakeholders have included: people with an unspecified psychiatric diagnosis (Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008), individuals affected by BP (Trippitelli et al., 1998; Laegsgaard et al., 2009) or MDD (Laegsgaard et al., 2009), people with multiple relatives affected by BP (Jones et al., 2002; Meiser et al., 2005, 2008), psychiatrists (Jones et al., 2002; Hoop et al., 2010), psychology students (Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008), and the general public (Wilde et al., 2010). This interest in psychiatric genetic testing seems to remain even without available preventative treatment options (Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008, 2009) and even if results offer only a probabilistic rather than definitive risk (Wilde et al., 2010).

In spite of the positive attitudes toward genetic testing for mood disorders demonstrated by these studies, key related topics have not been explored in depth. There is limited research examining: specific reasons why individuals are interested in genetic tests for mood disorders (Trippitelli et al., 1998; Mesier et al., 2008; Wilhelm et al., 2009), how the level of test predictability affects interest in genetic testing for mood disorders, and the preferred manner to receive genetic test results for mood disorders (Wilde et al., 2010; Borry et al., 2010).

This study explored these issues with individuals with a personal and/or family history of mood disorders as well as individuals with no personal or family history of mood disorders. The study examined potential reasons why stakeholders might be interested in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders, how predictive value affects level of interest in testing and preferences for the best manner to receive test results. It also hopes to add further insights to the ongoing debate about the potential impact of genetic attribution on the stigma associated with mental illness (Mechanic et al., 1994; Meiser et al., 2007; Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008; Meiser et al., 2008; Wilde et al., 2010).

METHODS

Study participants

Study participants consisted of attendees at Stanford University’s 7th annual Mood Disorders Education Day. The Mood Disorders Education Day (MDED) is a free educational event hosted by Stanford’s Bipolar Disorders Clinic for patients, caregivers, educators and community members interested in learning more about mood disorders. Surveys were distributed to MDED attendees and collected throughout the event.

Measure

The survey consisted of 14 questions designed to address MDED attendees’ opinions on a variety of topics related to genetic testing for risk of mood disorders (see Appendix 1). The survey included one demographic question, six questions assessing interest in genetic testing for mood disorders, two questions addressing reasons stakeholders might be interested in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders, and five questions evaluating stakeholders’ views about potential clinical applications of genetic testing for mood disorders. Nine questions utilized the Likert scale to measure degree of agreement or disagreement with provided statements.

The questionnaire was developed specifically for this study based on existing research on attitudes towards psychiatric genetic research and testing (Austin et al., 2006; Wilde et al., 2010, 2011) and input from a geneticist and a psychiatrist specializing in mood disorders research. Several questions for the survey were contributed from an unpublished study performed as part of Ms. Kuzmich’s graduate work (Kuzmich, 2011).

Analysis

Each collected survey received a unique identifying code and responses were entered into a spreadsheet. Responses to Likert scale questions were collapsed into three categories to capture positive, neutral or negative answers (e.g. “agree or strongly agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, and “disagree or strongly disagree”). Descriptive statistics were analyzed using the Predictive Analytics SoftWare Statistics SPSS program, version 18.0.

The Stanford University Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study and all participation was anonymous.

RESULTS

Participant demographics

Three hundred surveys were distributed throughout the course of the Stanford 7th annual MDED event. Approximately half (N= 147) of survey recipients completed and returned the surveys (see Table I). There were no significant differences in responses between respondents with a personal history of a mood disorder and respondents with only a family history of mood disorders; thus responses of these two groups were combined. Also, because few mental health professionals participated in the study (N= 10), this group was combined with those who selected the category “other,” to create a comparison group of respondents with no personal or family history of mood disorders. Respondents in the “other” category typically identified themselves as: academics interested in the topic, mental health advocates, or students at Stanford. The resulting two groups for comparison purposes were 1) people with a personal and/or family history of mood disorders (N= 116) and 2) people with no personal or family history of mood disorders (N= 31).

Table I.

Demographics

| N=147 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | N=116 | |

| Personal history of mood disorder | 29 | 20% |

| Family history of mood disorder | 70 | 48% |

| Personal & family history of mood disorder | 17 | 12% |

| Group 2 | N=31 | |

| Mental health care professional | 10 | 7% |

| Other | 21 | 14% |

Interest in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders(see Table II)

Table II.

Comparison of survey responses: Respondents with a personal history (PH) and/or family history (FH) of mood disorders (MD) versus respondents with no personal history or family history of mood disorders

| Survey question | PH &/or FH of MD |

No PH or FH of MD |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total per group | N=116 | 79% | N=31 | 21% | N=147 | 100% |

| MDs are caused by | ||||||

| Almost entirely by genes | 4 | 3% | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3% |

| More by genes but with some effects of life experience | 52 | 45% | 9 | 29% | 61 | 41% |

| By both genes and life experiences | 56 | 48% | 21 | 68% | 77 | 52% |

| Developing genetic tests for MDs is | ||||||

| Good | 92 | 79% | 21 | 68% | 113 | 77% |

| Neither good nor bad | 17 | 15% | 8 | 26% | 26 | 18% |

| Bad | 5 | 4% | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3% |

| Interest in testing with high certainty (90%) | ||||||

| Interested | 95 | 82% | 16 | 52% | 111 | 76% |

| Neutral | 7 | 6% | 8 | 26% | 15 | 10% |

| Not interested | 13 | 11% | 7 | 23% | 20 | 14% |

| Interest in testing with moderate certainty (20%) | ||||||

| Interested | 52 | 45% | 8 | 26% | 60 | 41% |

| Neutral | 22 | 19% | 10 | 32% | 32 | 22% |

| Not interested | 39 | 34% | 13 | 42% | 52 | 35% |

| Level or predictive value- factor in decision to test | ||||||

| Agree | 66 | 57% | 16 | 52% | 82 | 56% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 26 | 22% | 8 | 26% | 34 | 23% |

| Disagree | 19 | 16% | 7 | 23% | 26 | 18% |

| Increasing genetic knowledge will de-stigmatize MDs | ||||||

| Agree | 72 | 62% | 20 | 65% | 92 | 63% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 17 | 15% | 5 | 16% | 22 | 15% |

| Disagree | 23 | 20% | 8 | 26% | 29 | 20% |

|

Likelihood MD genetic test will effect pregnancy

decision |

||||||

| Likely | 37 | 32% | 9 | 29% | 46 | 31% |

| Neutral/Unsure | 54 | 47% | 11 | 35% | 65 | 44% |

| Unlikely | 15 | 13% | 10 | 32% | 25 | 17% |

|

Decisions to continue pregnancy based on MD genetic

test |

||||||

| Good | 29 | 25% | 4 | 13% | 33 | 22% |

| Neither good nor bad | 40 | 34% | 12 | 39% | 52 | 35% |

| Bad | 37 | 31% | 15 | 48% | 52 | 35% |

| MD test results- motivation to seek professional help | ||||||

| Agree | 92 | 79% | 21 | 68% | 113 | 77% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13 | 11% | 7 | 23% | 20 | 14% |

| Disagree | 9 | 8% | 3 | 10% | 12 | 8% |

| MD test results- motivation to change health behavior | ||||||

| Agree | 81 | 70% | 19 | 61% | 100 | 68% |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 25 | 22% | 10 | 32% | 35 | 24% |

| Disagree | 7 | 6% | 2 | 6% | 9 | 6% |

| Interest in genetic test for MDs vs. other conditions | ||||||

| More interested in tests for MDs | 28 | 24% | 1 | 3% | 29 | 20% |

| About the same | 74 | 64% | 22 | 71% | 96 | 65% |

| Less interested in tests for MDs | 10 | 9% | 8 | 26% | 18 | 12% |

| Best way to receive MD genetic test results | ||||||

| Directly to individual with no mediator | 18 | 16% | 4 | 13% | 22 | 15% |

| Through one’s primary physician | 25 | 22% | 10 | 32% | 35 | 24% |

| Through a genetic counselor | 36 | 31% | 10 | 32% | 46 | 31% |

| Through a psychiatrist or psychologist | 45 | 39% | 12 | 39% | 57 | 39% |

The large majority of respondents (97%) believed that genetics play a significant role in causing mood disorders and 77 percent were in favor of genetic testing for mood disorders. Fifty-six percent of respondents believed that a genetic test’s positive predictive value for a mood disorder would be a big factor in their decision whether or not to get tested. While 76 percent of respondents were interested in genetic tests with a high predictive value, only 41 percent of respondents were interested in testing using a genetic test with a moderate predictive value.

The majority of respondents (65%) were equally interested in genetic testing for mood disorders and genetic testing for other somatic illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes or cancer. However, respondents who believed mood disorders are caused “almost entirely by genes” or “more by genes but with some effects of life experiences” were more likely to be interested in genetic testing for mood disorders in comparison to other somatic illnesses than respondents that believed mood disorders are caused by “both genes and life experiences- around 50-50” or “almost entirely by life experiences” (p= 0.01).

In comparing the two groups, there were no significant differences in responses, except regarding two variables (see Table II). People with a personal and/or family history of mood disorders were significantly more interested in highly predictive genetic tests for risk of mood disorders than people with no personal or family experience (p<0.001). Additionally, people with a personal and/or family history of mood disorders were also significantly more interested in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders compared to other physical disorders than people with no personal or family history of mood disorders (p= 0.003).

Reasons for interest in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders

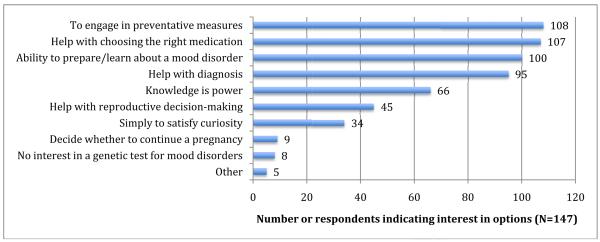

When asked to choose among a list of potential reasons participants would be interested in taking a genetic test for risk of a mood disorder either personally or for a patient, respondents checked off reasons from a list of 10 choices, including the options to offer a different unlisted reason or to select “no interest” (see Figure I). The most frequently selected reason was: “Potential to engage in preventative measures” (73%), and the option least chosen was: “To decide whether or not to continue a pregnancy” (6%).

Figure I.

Reasons for interest in a genetic test for risk of mood disorders

Respondents also expressed optimism that genetic testing for mood disorders would lessen the stigma surrounding these illnesses. The majority of respondents (63%) believed that increasing genetic knowledge about mood disorders would help to de-stigmatize these disorders.

Clinical applications of genetic testing for risk of mood disorders

Respondents believed that genetic testing for risk of mood disorders would yield significant clinical benefits. The majority of participants believed that genetic test results indicating an elevated risk for developing a mood disorder would make a person more willing to seek professional help (77%) and would motivate someone to change his/her health behavior (68%).

Thirty-one percent of respondents thought it likely that prenatal genetic test results for risk of mood disorders would affect an individual’s decision about whether or not to continue with a pregnancy. The majority of respondents was either unsure (44%), believed this to be unlikely (17%) or did not provide a response (7%). A small minority of respondents (22%) believed that making decisions about whether or not to continue with a pregnancy based on prenatal genetic test results for mood disorders was a “good” thing. The majority of respondents (78%) was “unsure”, believed this to be “bad”, or provided no response. The two items regarding how likely participants thought prenatal genetic testing for mood disorders would affect someone’s decision about whether or not to continue a pregnancy and whether making decisions about continuing a pregnancy based on tests results was a good or bad thing resulted in the greatest number of “unsure” responses or lack of responses compared to any other survey item.

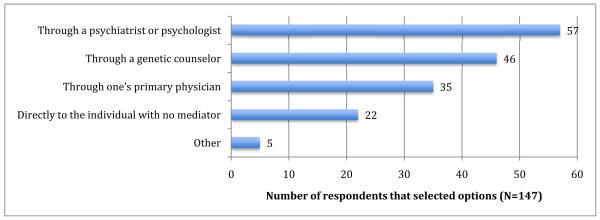

As for the best manner in which these genetic tests for mood disorders should be made accessible to people, the most widely selected response was through a psychiatrist or psychologist (57%) and the least selected option was directly to the individual with no mediator (22%) (see Figure II).

Figure II.

Best method to receive genetic test results

DISCUSSION

Most respondents believed that genetics play a significant role in causing a mood disorder, were optimistic that developing genetic tests for mood disorders is a good thing, would be interested in taking a genetic test for risk of mood disorders (although interest in testing significantly decreased if the test were only moderately predictive instead of highly predictive), and were equally interested in genetic testing for mood disorders and other somatic illnesses. Participants were most interested in testing if results allowed them to engage in preventative measures and least interested in testing for help deciding whether or not to continue a pregnancy. They were unsure whether or not prenatal genetic testing for risk of mood disorder would affect someone’s decision about whether or not to continue a pregnancy and if prenatal decisions based on testing would be a good or a bad thing. Most respondents were optimistic that genetic test results for risk for mood disorders would help de-stigmatize these disorders, make a person more willing to seek professional help and would motivate someone to change his/her health behavior. The preferred manner to receive test results, indicated by respondents, was through a psychiatrist or psychologist and the least preferred method was directly to the individual with no mediator.

Interest in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders

The majority of respondents believed that genetics play a significant role in causing a mood disorder. This finding is similar to results from a previous study that asked participants specifically about the role of genetics in causing depression (Wilhelm et al., 2009). The large majority of respondents was in favor of developing genetic tests for these illnesses, and was interested in personally taking a test if the test results revealed a high predictive value. These results are also congruent with previous studies that found high rates of interest in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders among patients with BP (Trippitelli et al., 1998; Laegsgaard et al., 2009), MDD (Laegsgaard et al., 2009), and mental health professionals (Jones et al., 2002; Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008; Hoop et al., 2010). However, in a previous study of psychiatric geneticists, we found that researchers were relatively less optimistic about the ability of genetic tests for mood disorders to achieve even moderate levels of clinical validity and utility (Erickson and Cho, 2011).

The expressed level of interest in genetic testing for level of risk for mood disorders dropped significantly as positive predictive value decreased, an expected and previously demonstrated trend (Meiser et al., 2008). This drop in interest based on lower positive predictive value is an important finding to note. Health care providers and direct to consumer testing companies must be sure to clearly explain how predictive and meaningful test results are to potential users since consumers may be significantly less likely to use current and future genetic tests for risk of mood disorder if they understand that these tests are not highly predictive and may not be clinically meaningful.

People with a personal and/or family history were significantly more interested in highly predictive genetic tests and genetic testing for mood disorders compared to other somatic disorders than people without a personal or family history of mood disorders. These differences are understandable since people with a personal experience of mood disorders may view testing for risk of mood disorders as more relevant or helpful to them.

Reasons for interest in a genetic test for risk of mood disorders

Participants were most interested in taking a genetic test for risk of a mood disorder when the results might permit them to: 1) engage in preventative measures, 2) help in selecting the most effective medication and, 3) prepare for and/or learn more about the disorder. Previous studies found similar results, with an emphasis on preventative or preparatory measures. A study that surveyed families with multiple cases of BP indicated that the primary reasons for interest in genetic testing for mood disorders were to: “provide a basis for tailoring medications” or to “help people proven to have a genetic variation avoid stressors” (Meiser et al., 2008). A recent study of attitudes toward genetic testing for depression demonstrated that most respondents anticipated benefits of earlier treatment and the potential to prevent the onset of depression (Wilhelm et al., 2009). Our results are consistent with previous findings demonstrating that the main interest in genetic testing for mood disorders may be pre-emptive or early diagnosis so patients have the ability to engage in preventative measures or at least to prepare for the illness more effectively.

The response selected least often as a reason of interest to test for genetic risk of mood disorders was to decide whether or not to continue a pregnancy. Psychiatric genetic researchers have expressed concern that there might be an increasing demand for prenatal tests for mood disorders before valid or reliable tests have been developed (Erickson and Cho, 2011). Given the low predictive power of psychiatric genetic tests, decisions not to have children based on the results of such a test would be unjustified (Wilde et al., 2011). In spite of these concerns, existing research supports this study’s findings that there is a high level of trepidation and uncertainty about prenatal testing for mood disorders among many potential consumers (Smith et al., 1996; Trippitelli et al., 1998; Jones et al. 2002; Meiser et al., 2008). Studies indicate that there is significantly less interest in prenatal genetic tests for risk of mood disorders than for other somatic illnesses (Smith et al., 1996; Laegsgaard et al., 2009), and testing prenatally for mood disorders does not seem to be one of potential users’ primary hopes for the advancement of genetic research (Jones et al., 2002; Meiser et al., 2008). The relatively high rate of uncertain responses regarding prenatal testing among stakeholders underscores that this potentially controversial issue is a concern for which stakeholders perceive a need for more and better information.

The majority of respondents believed that increasing genetic knowledge about mood disorders would help to de-stigmatize these disorders. In contrast with less stigmatized chronic physical conditions, individuals with psychiatric disorders are among the most highly stigmatized groups in society (Mechanic et al., 1994; Smith et al., 1996; Meiser et al., 2007). Existing literature presents contradicting points of view about the potential impact of genetic attribution on the stigma associated with mood disorders. On the one hand, some theories claim that evidence of a genetic component for mood disorders shifts responsibility away from the self to one’s biology, thus reducing feelings of blame or guilt, and consequently the stigma associated with these disorders. Conversely, an opposing perspective claims that a genetic model for mood disorders may increase the perceived seriousness of these disorders and may label people pre-symptomatically, thus increasing stigma (Spriggs et al., 2008). Stakeholder analyses have demonstrated that both perceptions can occur as a result of obtaining genetic information (Mesier et al., 2007; Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008; Wilde et al., 2010; Erickson and Cho, 2011). Further studies should examine stakeholder views about this debate in order to attain a better understanding of the underlying principles behind both perspectives and perhaps to reach a clearer consensus.

Clinical applications of genetic testing for risk of mood disorders

In addition to decreasing stigma, the majority of survey respondents believed that genetic test results indicating an elevated risk for developing a mood disorder would lead to significant clinical benefits such as making a person more willing to seek professional help and more willing to change his/her health behavior. These results are consistent with previous stakeholder studies. Anticipated favorable behavior changes have included: reducing life stress and drug or alcohol consumption, increasing exercise, (Wilde et al., 2009), learning positive coping skills (Wilde et al., 2011), modifying environmental risk factors (Senior et al., 2000), and willingness to undertake cognitive and behavioral interventions at a pre-symptomatic stage (Wilde et al., 2009). In the event that more clinically meaningful genetic tests for mood disorders become available, actual behavior changes should be examined and not merely intentions to change, given that it is often difficult to predict actions based on intentions (Lerman et al., 2002; Marteau et al., 2010).

The majority of respondents indicated a preference to receive genetic test results for risk of mood disorders from a psychiatrist or psychologist. Although mental health professionals may be the preferred personnel to explain mood disorders and diagnose patients, they may currently not be adequately trained to interpret genetic test results. Although various mental health professionals have indicated interest in the potential for psychiatric genetic tests (Braff and Freedman, 2008; Hoop et al., 2008; Laegsgaard and Mors, 2008; Hoop et al., 2010), they have also expressed feeling unqualified to interpret genetic test results accurately (Berg et al., 2008; McBride et al., 2010; Hoop et al., 2010). A recommendation would be for psychiatrists to receive more extensive genetics training on an ongoing basis. Alternatively, it might be better for consumers to receive genetic test results for risk of mood disorders from a genetic counselor while simultaneously having additional access and support available to them from a psychiatrist or psychologist.

Limitations

The sample selected for this study represents both a strength and a limitation. Although the purpose of the study was to explore opinions and beliefs of individuals with a high level of interest and involvement in the matter of genetic testing for mood disorders this fact can also be seen as a limitation. The nature of the sample, well informed about these illnesses and actively seeking the latest information about these disorders by attending a university-sponsored educational event, represent a highly motivated group of people, perhaps more open to new types of research and diagnostic methods than others. Thus, the findings may not be representative of the population at large. A second limitation pertains to the nature of the instrument utilized. The study was a survey, and as is the case with all surveys, it had certain intrinsic limitations. Participants could only answer the questions posed; they did not have the opportunity to add to or to expand upon issues they considered important, or to share more deeply the reasoning behind their answers. A third possible limitation is that hypothetical interest in genetic testing is a poor predictor of actual test uptake (Lerman et al., 2002); therefore the high numbers of participants in this study expressing intention to test may not reflect the actual future demand for psychiatric genetic testing. The uptake of such testing, once clinically available, could be lower than that predicted by intention to test (Lerman et al., 2002; Wilde et al., 2010).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that there is a high level of interest in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders, especially among people with a personal and/or family history of mood disorders. There is also significant optimism regarding societal and clinical benefits that can result from genetic testing. However, interest in genetic testing for risk of mood disorders is greatly affected by the predictive value of the test. Because of the significant decline in interest when the tests were perceived as moderately instead of highly predictive, a recommendation of this study is that providers clearly and accurately portray the predictiveness of these tests to consumers. This is especially true since genetic tests for mood disorders are not likely to attain even the moderate levels of predictive value presented in our survey. Interest to participate in testing for risk of mood disorders may (appropriately) decline if people understand how low predictive values currently are and will likely be for some time to come (Erickson and Cho, 2011).

Lastly, given the finding that people would rather receive genetic test results from psychiatrists or psychologists, this study recommends strengthening and increasing the area of genetics education for mental health professionals during their professional education as well as on a continuing education basis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Douglas Levinson, Ms. Kelly Ormond and Ms. Lili Kuzmich who contributed several questions from an unpublished study performed as part of Ms. Kuzmich’s graduate work, and to Ms. Ormond for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author disclosure: All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jessica A Erickson, Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics Center for Integration of Research on Genetics and Ethics 1215 Welch Rd Modular A Stanford CA, 94305.

Mildred K. Cho, Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics 1215 Welch Rd Modular A Stanford CA, 94305.

References

- Ainsley JN. Depression under stress: ethical issues in genetic testing. BJPsych. 2009;195:189–190. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin JC, Smith GN, Homer WG. The genomic era and perceptions of psychotic disorders: genetic risk estimation, associations with reproductive decisions and views about predictive testing. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141:926–928. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Davydow DS, Kendler KS. Psychiatric ‘diseases’ versusbehavioral disorders and degree of genetic influence. Psychol Med. 2010;41.1:33–40. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000084X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss CS, Schiabor KM, Schork NJ. Human behavioral informatics ingenetic studies of neuropsychiatric disease: multivariate profile-based analysis. Brain Res Bull. 2010;83:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borry P, Howard HC, Senecal K, Avard D. Health-related direct-toconsumergenetic testing: a review of companies’ policies with regard to genetic testing in minors. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:51–59. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C, Fryer-Edwards K. The ethical challenges of direct-to-consumer genetic testing. J Bus Ethics. 2008;77:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL, Freedman R. Clinically responsible genetic testing in neuropsychiatric patients: A bridge too far and too soon. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:952–955. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichon S, Craddock N, Daly M, Faraone SV, Gejman PV, Kelsoe J, Lehner T, Levinson DF, Moran A, Sklar P, Sullivan PF. Genomewide association studies: history, rationale, and prospects for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:540–556. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08091354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couzin J. Science and commerce: Gene tests for psychiatric risk polarize researchers. Science. 2008;319:274–277. doi: 10.1126/science.319.5861.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JA, Cho MK. Ethical considerations and risks in psychiatric genetics: preliminary findings of a study on psychiatric genetic researchers. AJOB Prim Res. 2011;2(4):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Facio FM, Brooks S, Loewenstein J, Green S, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Motivators for participation in a whole-genome sequencing study: imp ications for translational genomics research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011:1–5. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop JG, Roberts LW, Hammond KAG, Cox NJ. Psychiatrists’ attitudes regarding genetic testing and patient safeguards: A preliminary study. Genet Test. 2008;12:245–252. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop JG, Lapid MI, Paulson RM, Roberts LW. Clinical and ethical considerations in pharmacogenetic testing: Views of physicians in 3 “early adopting” departments of psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:745–753. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04695whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoop JG, Salva G, Roberts LW, Zisook S, Dunn LB. The current state of genetics training in psychiatric residency: views of 235 U.S. educators and trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(2):109–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.34.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson K, Javitt G, Burke W, Byers P. ASHG statement on direct-toconsumer genetic testing in the United States. American J Hum Genet. 2007;1:635–637. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000292086.98514.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I, Scourfield J, McCandless F, Craddock N. Attitudes towards future testing for bipolar disorder susceptibility genes: a preliminary investigation. J Affect Disord. 2002;71:189–193. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BR, Tsai DFC. Whole-genome association studies for multigenic diseases: ethical dilemmas arising from commercialization—the case of genetic testing for autism. J Med Ethics. 2010;36:440–444. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.031385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T. Molecular genetics of bipolar disorder and depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;61:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmich L. Attitudes toward genetic testing for mood disorders. 2011. unpublished study.

- Laegsgaard MM, Kristensen AS, Mors O. Potential consumers’ attitudes toward psychiatric genetic research and testing and factors influencing their intentions to test. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13(1):57–65. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laegsgaard MM, Mors O. Psychiatric genetic testing: Attitudes and intentions among future users and providers. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:375–384. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CM, Wade CH, Kaphingst KA. Consumers’ views of direct-toconsumer genetic information. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2010;11:427–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenfield S, Davis D. Effects of illness attribution and depression of the quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:155–164. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Kasparian NA, Mitchell PB, Strong K, Simpson JM, Tabassum L, Mireskandari S, Schofield PR. Attitudes to genetic testing in families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Genet Test. 2008;12(2):233–243. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Mitchell PB, Kasparian NA, Strong K, Simpson JM, Mireskandari S, Tabassum L, Schofield PR. Attitudes towards childbearing, causal attributions for bipolar disorder and psychological distress: a study of families with multiple cases of bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1601–1611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff D, Khoury M. Personal genomics: information can be harmful. Eur J Clinl Invest. 2010;40(1):64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LB, Sapers B, Reus VI, Freimer NB. Attitudes towards bipolar disorder and predictive genetic testing among patients and providers. J Med Genet. 1996;33:544–549. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.7.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits KM, Smits LJM, Schouten J, Peeters F, Prins MH. Does pretreatment testing for serotonin transporter polymorphisms lead to earlier effects of drug treatment in patients with major depression? A decision-analytic model. Clin Ther. 2007;29:691–702. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs M, Olsson CA, Hall W. How will information about the genetic risk of mental disorders impact on stigma? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:214–220. doi: 10.1080/00048670701827226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trippitelli CL, Jamison KR, Folstein MF, Bartko JJ, DePaulo JR. Pilot study on patients’ and spouses’ attitudes toward potential genetic testing for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):899–904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A, Meiser B, Mitchell PB, Schofield PR. Community attitudes towards mental health interventions for healthy people on the basis of genetic susceptibility. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43:1070–1076. doi: 10.3109/00048670903179152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A, Meiser B, Mitchell PB, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Schofield PR. Community interest in predictive genetic testing for susceptibility in major depressive disorder in large national sample. Psychol Med. 2010:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde A, Meiser B, Mitchel PB, Schofield PR. Public interest in predictive genetic testing, including direct-to-consumer testing, for susceptibility to major depression: preliminary findings. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:47–51. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Meiser B, Mitchell PB, Finch AW, Siegel JE, Parker G, Schofield PR. Issues concerning feedback about genetic testing and risk of depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:404–410. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CF, Kroese M. Evaluation of genetic tests for susceptibility to common complex diseases: why, when and how? Hum Genet. 2010;127:125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0767-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]