Abstract

Background

With growing interest in the CBPR approach to cancer health disparities research, mechanisms are needed to support adherence to its principles. The Carolina Community Network (CCN), 1 of 25 Community Network Programs funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), developed a model for providing funds to community-based organizations.

Objectives

This paper presents the rationale and structure of a Community Grants Program (CGP) model, describes the steps taken to implement the program, and discusses the lessons learned and recommendations for using the grants model for CBPR.

Methods

Three types of projects—cancer education, implementation of an evidence-based intervention, and the development of community–academic research partnerships—could be supported by a community grant. The CGP consists of four phases: Pre-award, peer-review process, post-award, and project implementation.

Results

The CGP serves as a catalyst for developing and maintaining community–academic partnerships through its incorporation of CBPR principles.

Conclusions

Providing small grants to community-based organizations can identify organizations to serve as community research partners, fostering the CBPR approach in the development of community–academic partnerships by sharing resources and building capacity.

Keywords: NCI’s Community Networks Program, cancer health disparities, community-based participatory research, community–academic research partnerships, microgrants

Since the late 1990s, much attention has been focused on ways of reducing the well-documented and disproportionate burden of disease among African Americans compared with white Americans, reflected in the increasing incidence and mortality rates across a number of disease categories.1 The reasons for racial/ethnic health disparities are complex and multifactoral. They include individual behaviors and preferences, cultural beliefs, biological factors, environmental factors, differential health interventions, bias among treating providers, public and private health policies, and differential access to healthcare services, in addition to socioeconomic factors.2

North Carolina is the 10th most populous state in the United States with about 9.5 million people.3 It is estimated that 4 in 10 North Carolinians will be diagnosed with cancer during their lives.4 Cancer is now the leading cause of death in the state, surpassing heart disease.5 In 2006, 17,267 North Carolinians died from cancer. Substantial disparities exist in incidence and outcomes across racial and ethnic groups, with African Americans experiencing the greatest cancer burden with regard to cancer incidence, survival, and mortality when compared with white Americans.6 African Americans bear the heaviest cancer burden, with prostate cancer incidence that is 66% higher than the Caucasian rate. Similarly, African Americans have higher colorectal cancer incidence rates (54.8/100,000) than Caucasians (44.8/100,000). For breast cancer, African-American women have an overall cancer mortality rate that is nearly 20% higher than Caucasian women.4,5

In 2004, the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities established the Community Networks Program (CNP), an outgrowth of several NCI cancer health disparities initiatives. The 25 CNP sites that operate across the country vary in size, scope, and priority populations, but are united by a common goal to increase cancer awareness in the community and to conduct community-based participatory cancer disparities research.7 The CCN to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities is one CNP whose mission is to reduce breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer disparities among adult African Americans in North Carolina through education, research, and training. The CCN is a regional cancer network encompassing 13 of the state’s 100 counties (Central and Eastern parts of the state), based at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. The two regions reflect the targeted areas of the UNC Centers for Community Research, a community-based research infrastructure. During the initial 2 years of the CNP grant, CCN worked closely with partners from two community organizations—a grassroots community organization and a community-based health agency. These organizations were invited to become CCN partners based on their shared interest in reducing cancer disparities and their previous experience in working with UNC faculty on research and/or educational activities.

Community partner activities focused on enhancing existing educational and outreach activities, such as trainings for faith-based organizations and dissemination of educational materials through community health fairs and community clinics. Initial partners received $10,000 to support the enhancement of their existing activities. With the charge to increase the number of community partners, CCN recognized the need for a mechanism that could aid in increasing the number of community partners. CCN developed the CGP in 2007 as a model for increasing the number of network partners from the community who could implement and promote cancer education, implement evidence-based cancer programs, and participate in research as an engaged partner to reduce cancer disparities in North Carolina.

The CGP model follows the microgrants concept designed from the microfinancing program originally developed to provide small business loans for economic stimulus in developing countries.8 In 2001, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, introduced the concept of microgrants in the United States in an attempt to explore new ways to expand the participation of community-based organizations to meet the Healthy People 2010 objectives.9,10 Microgrants are based on the same general principles as microfinancing, with the major difference being that community-based organizations receive funds based on qualified applications instead of on a loan/credit basis.11

To date, the literature that explores methods for leveraging community–academic partnerships through the microgrant concept is sparse. The goals of this paper are to present the rationale and structure of a CGP model and describe its implementation, along with lessons learned and recommendations for using the grants model for CBPR.

Methods

Award Types

Three types of grants are made available: (1) Cancer education grants, (2) implementation of evidence-based cancer programs, and (3) the development of community–academic research partnerships. Cancer education grants provide support to increase awareness of cancer screening benefits, the use of preventive health behaviors, or the awareness of treatment options, and range in funding from $500 to $5,000 for each proposal. Evidence-based cancer program grants ranging from $500 to $5,000 are available to support the implementation of Body & Soul: A Celebration of Healthy Eating and Living to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among African Americans through the church community. The development of community–academic research partnerships is the final type of grant offered and ranges in funding from $3,000 to $10,000. The scope of the research award entails any of the following: Establish a relationship between a community group and academic researcher, or conduct a baseline assessment of a research need, or develop a research question with the ultimate goal of informing larger, externally funded CBPR research projects.

CGP Infrastructure

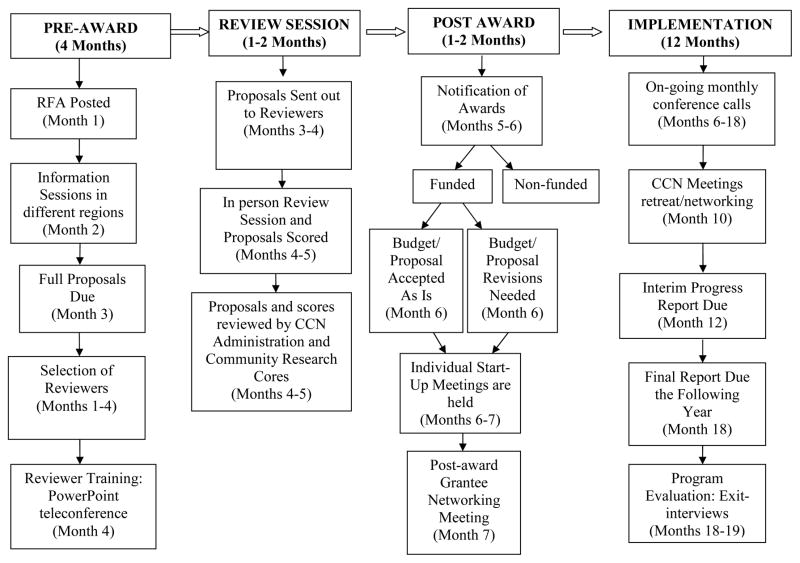

The CGP’s structure includes an annual request for applications (RFA), a peer-review process, and technical assistance provided during the pre-award and post-award periods. Figure 1 provides additional information on the sequence of events in an annual cycle of the program. The program is divided into four phases: Pre-award, review session, post-award, and implementation.

Figure 1. CCN’s Community Grant Program Awards Cycle*.

* The timeline is based on an 18-month planning and implementation schedule.

Pre-Award

The pre-award process begins with the issuance of a RFA. Eligible organizations include health care agencies, community-based, faith-based, and other community groups that serve 1 or more of the 13 CCN targeted counties. Applications must focus on any of the targeted CCN cancers—breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer—in the adult African-American population; conduct a cancer education, evidence-based program, or a cancer participatory research project; and include an evaluation plan. The CGP provides funding for 12 months and organizations have the opportunity to submit subsequent new applications after their funded project ends. There are specific budget guidelines that describe how the allocated funds can be used.

Although the development of a clear and concise RFA is crucial to the CGP model, the CCN has also established a comprehensive dissemination plan, including (1) information sessions in the community, (2) e-mail distribution lists, and (3) individual consultations with grant recipients. The information sessions are held between the release of the RFA and the application deadline. A CCN staff is present at each of these sessions to discuss the CGP in general and walk the community members through the application and review process. Among CCN staff are the Community Outreach Specialists (COS) who are positioned in the community as staff in each UNC Center for Community Research, a community research infrastructure. The COS has master’s degree training in public health and lives in or has ties to the targeted community region. The primary duties of the COS are to educate the community about research and cancer health disparities, and to facilitate research and education between the community and university. Resources like technical assistance and educational materials are provided by the Network’s COS to help strengthen the capacity of community-based organizations to successfully implement an activity. The COS also meets with community groups and identifies UNC researchers who can share their research expertise and cancer content knowledge with interested community organizations. Each COS is supported by a local Community Advisory Board that provides guidance and feedback on projects.

Peer Review Process

An in-person review session, generally lasting 2 to 3 hours, is held to review all applications. Each application is discussed and scored by two reviewers—an academic reviewer and a community reviewer. Reviewers are selected based on expertise, interest, availability, and community experience. The community reviewer is selected primarily based on their past affiliation with community–academic research projects. CCN Community Partners who did not submit an application were also eligible to review the proposals. Reviewer training is held before the review session to orient reviewers to the CGP model, to the NIH-style review process and the reviewer score sheet used to determine scores. Applications are evaluated based on their responsiveness to the review criteria. Reviewers provide a single score for each of the review criteria that are then averaged to get a composite score across all aspects of the proposal. Funding decisions are made by the CCN leadership using the proposal review scores, project type, geographic region, and potential impact on the priority community.

Post-Award

After the review session, applicants are notified of their funding status and provided with detailed feedback on all review criteria. The COS schedule individual start-up meetings with grant recipients to follow-up on any issues or questions raised by the review committee, discuss the process for obtaining and using the project funds, and address questions regarding budget revisions, adjustments to project plans, and potential areas for collaboration with other CCN members (community and academic members). Funds are made available to each community partner via service agreements with the University that include a signed Memorandum of Understanding, an agreement required by the NCI CNP to ensure clear, realistic expectations between each network initiative and the community organization.

Project Implementation

During the funding period, awardees are required to provide a 6-month progress report and a 12-month final report. Regular networking meetings are held to share CCN-related information and to provide a venue for cross-community sharing among the grantees. Monthly conference calls throughout the award period also serve as the foundation for on-going communications between grantees and the rest of the CCN.

Results

Over the 2-year period with the CGP, the network has increased the number of community partners from its initial 2 community partners to 13. Approximately, $79,000 have been provided to fund community partners through the CGP model. Some of the organizations are large, with multiple staff and sufficient resources. Smaller organizations are beginning to use CCN funding to leverage additional funding and staff.

In the first year of the CGP, CCN received 21 applications and funded eight organizations for a total of $38,965 in funding. Fifteen applications were received in year two and seven organizations were funded with a total of $40,000 in funding. Three of the CGP organizations initially funded via the grants program received meritorious application scores and were awarded another round of funding in year two. CCN has funded organizations that represent three distinct groups: 40% community-based, 33% faith-based, and 27% health agencies. Nearly 60% of projects have been focused on cancer education, 27% on dissemination of evidence-based programs, and 13% on participatory research.

Discussion

With an increased emphasis on the use of the community-based participatory research approach to actively involve the targeted community groups in addressing health disparities, the CGP model served as an important mechanism for ensuring that CBPR principles such as the equitable distribution of resources, capacity building, recognition of community strengths and resources, and the community as a unit of identity were adhered to.12 In implementing the CGP model, we were able to meet our goal to increase the number of community-based organizations as partners in the CNP. As a result of these partnerships, we were also able to expand our efforts in promoting cancer education and outreach activities and implementing evidence-based intervention programs and strategies. In achieving these successes, we also encountered challenges that have resulted in several lessons learned.

In trying to ensure an equitable distribution of resources whereby research dollars are provided directly to the community, we had to address the financial structure at an academic institution and the implicit imbalance of power created by the academic institution distributing grants to community organizations. Based on feedback from our initial community partners, we decided to allow organizations to choose the type of project (i.e., education, implementation of an intervention, research), use their own strategies, and to develop their own budgets. We also learned that it was important to provide the funded community-based organizations with information on how the academic financial structure works. This strategy reflected value in the community’s ideas on how best to approach their community to address cancer health disparities.

A second lesson learned was that, in addition to the provision of monetary resources through the grants mechanism, access to other resources within the CNP needed to be shared. For example, community partners were able to request technical assistance from the COS or other services in the network (e.g., access to expert speakers, development of materials). The COSs were accessible to the community by meeting individually with prospective community-based organizations to offer guidance in developing the proposal and suggesting resources that could be leveraged for the project. As a result, the scores received by year two applicants were higher than those given in the first year. Improvements in the methods/processes for project implementation and the inclusion of evaluation measures contributed to the improved scores.

A third lesson learned was experienced during the grant review process. To ensure a balanced review process, we paired reviewers—an academic reviewer and a community reviewer—to review each application. Although we initially felt this strategy would allow for an equal voice, the review criteria based on the five point National Institutes of Health process did not work for the community reviewers. We modified the review process so that each reviewer could review the proposal based on the criteria, but through their own lens. The two different perspectives enriched the review discussion by ensuring that the community viewpoint and proposed strategies were understood by the entire review committee.

A fourth lesson learned was the need to build an organization’s research capacity to become a community research partner. The community grants were available to all community organizations regardless of their level of organizational capacity. Hence, some of the community grantees were closer in readiness to becoming a research partner than those with limited to no experience in working with academia. It will be important to develop strategies for supporting the transition of organizations from education and outreach activities to research projects. For example, the transition may start by including community partners as advisors in research grants or training them to conduct aspects of the research process. In using the CGP as a platform for developing community research partners, the number of external CBPR grant applications will increase whereby needed resources to sustain efforts in the community can be leveraged. Another approach to building community research capacity may be to provide workshops tailored for the community on research topics such as human subjects, grant writing, evaluation, identifying and adopting an evidence-based intervention program, and so on.

We also learned that the time frame for completing the project needed to be lengthened from the required 12-month period. Many organizations were challenged to complete the project in time owing to delays in hiring staff, unexpected staff turnover, and the need for more upfront technical assistance around general project management issues. Extending the project period to 2 years would provide time needed for project implementation as well as the identification of subsequent funding to sustain the activity.

Last, we learned that building partnerships with a diverse group of organizations require diverse approaches to fostering partnerships and careful consideration should be given when deciding which groups are the best fit with the small grants structure. Health agencies are bound by their organization’s mission and objectives, and their agenda often is based on the structural and operational needs of the institution. In contrast, grassroots organizations are less restricted by existing guidelines and are more flexible in terms of tailoring programs to the needs of the community and goals of the grantor (CCN). Although health agencies are often able to meet the needs of the community to some degree by providing trainings and technical assistance to community-based organizations, the likelihood of melding to the mission of a research initiative can be challenging.

By adhering to the CBPR principles, the CGP approach to developing community research partners can naturally stand to build research capacity in the community, develop resources in the community, and provide communities with an awareness of the academic research culture. The CGP may be a useful mechanism for other CNPs or research initiatives that require the use of the CBPR approach and need a viable platform for engaging members of the community in various stages of organizational capacity in the research process. Based on 2 years of using the CGP, the model has served not only as a platform for developing partners in the community that did not exist before, but it also generated interest among the organizations to form partnerships among themselves and with academia, fostered the development of CBPR research projects and, last, increased the community’s understanding of the academic research enterprise.

Acknowledgments

The authors to thank Dr. Timothy Carey and Dr. Alice Ammerman for their editorial comments and direction as we prepared this paper.

The Carolina Community Network is supported by the National Cancer Institute’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities through its Community Networks Program (U01 CA 114629).

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. 2. Washington (DC): U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. Health people 2010. (2 vols) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vines A, Godley P. The challenges of eliminating racial and ethnic health disparities: Inescapable realities? Perplexing science? Ineffective policy? NC Med J. 2004;65:341–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. State and county quick facts. 2006 [cited 2010 Sep 17]. Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37000.html.

- 4.North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics. [cited 2010 Sep 17]. Available from: http://www.schs.state.nc.us/SCHS/CCR/

- 5.Carpenter WR, Beskow L, Blocker D, Forlenza M, Kim A, Pevzner E, et al. Towards a more comprehensive understanding of cancer burden in North Carolina: Priorities for intervention. NC Med J. 2008;4:275–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lisovicz N, Johnson R, Higginbotham J, Downey J, Hardy C, Fouad M, Hinton A, et al. The Deep South Network for Cancer Control: Building a community infrastructure to reduce cancer health disparities. Cancer. 2006;107(Suppl 8):1971–79. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman H, Vydelingum N. The role of the Special Populations Network Program in eliminating cancer health disparities. Cancer. 2006;107(Suppl 8):1933–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartwig K, Bobbitt-Cooke M, Zaharek M, Nappi S, Wykoff R, Katz D. The value of microgrants for community-based health promotion: Two models for practice and policy. J Public Health Management Practice. 2006;12:90–6. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200601000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobbitt-Cooke M. Energizing community health improvement: The promise of microgrants. Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2005;2(Suppl I):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson D, Smith L, Bruemmer B. Small-grant programs: Lessons from community-based approaches to changing nutrition environments. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2007;107:301–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caperchione C, Mummery K, Joyner K. WALK Community Grants Scheme: Lessons learned in developing and administering a health promotion microgrants program. doi: 10.1177/1524839908328996. [cited 2009 Mar 11]. Available from: http://hpp.sagepub.com/cgi/rapidpdf/1524839908328996v1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen A, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research for health. Sasn Francisco: Jossey-Bass; pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar]