Abstract

AIM: To identify severe adverse events (SAEs) leading to treatment discontinuation that occur during antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected cirrhotic patients.

METHODS: We identified all the articles published prior to December 2011 in the PubMed, Medline, Lilacs, Scopus, Ovid, EMBASE, Cochrane and Medscape databases that presented these data in cirrhotic patients. These studies evaluated the rate of SAEs leading to discontinuation of standard care treatment: Pegylated interferon (PegIFN) alpha 2a (135-180 μg/wk) or PegIFN alpha 2b (1 or 1.5 μg/kg per week) and ribavirin (800-1200 mg/d). Patients with genotype 1 + 4 underwent treatment for 48 wk, whereas those with genotypes 2 + 3 were treated for 24 wk.

RESULTS: We included 17 papers in this review, comprising of 1133 patients. Treatment was discontinued due to SAEs in 14.5% of the patients. The most common SAEs were: severe thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia (23.2%), psychiatric disorders (15.5%), decompensation of liver cirrhosis (12.1%) and severe anemia (11.2%). The proportion of patients who needed to discontinue their therapy due to SAEs was significantly higher in patients with Child-Pugh class B and C vs those with Child-Pugh class A: 22% vs 11.4% (P = 0.003). A similar discontinuation rate was found in cirrhotic patients treated with PegIFN alpha 2a and those treated with PegIFN alpha 2b, in combination with ribavirin: 14.2% vs 13.7% (P = 0.96). The overall sustained virological response rate in cirrhotic patients was 37% (95%CI: 33.5-43.1) but was significantly lower in patients with genotype 1 + 4 than in those with genotype 2 + 3: 20.5% (95%CI: 17.9-24.8) vs 56.5% (95%CI: 51.5-63.2), (P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION: Fourteen point five percent of HCV cirrhotic patients treated with PegIFN and ribavirin needed early discontinuation of therapy due to SAEs, the most common cause being hematological disorders.

Keywords: Liver cirrhosis, Hepatitis C virus, Adverse events, Sustained virological response

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a worldwide public health concern, affecting approximately 170 million people[1]. This condition is responsible for 25%-30% of global cases of cirrhosis and is the most common cause for liver transplantation[2]. Cirrhotic patients infected with HCV develop hepatic decompensation at a rate of 30% over 10 years and hepatocellular carcinoma at annual rates ranging from 3% to 8%[3,4].

In the last 10 years, pegylated interferon (PegIFN) and ribavirin became the standard of care (SOC) treatment in chronic HCV infection. The sustained virological response (SVR) rates range from 42% to 46% in patients with genotype 1 or 4 infection and from 76% to 82% in patients with genotype 2 or 3 infection[5-7]. In patients with liver cirrhosis, the SVR rate is even lower, at approximately 20% in genotype 1 or 4 infection and 55% in patients with genotype 2 or 3 infection[8]. Also, cirrhotic patients have a reduced tolerance to therapy[9,10] but the risk of further complications is smaller in patients who achieve SVR[11].

This systematic review aims to identify and analyze the severe adverse events (SAE) that lead to treatment discontinuation during treatment with PegIFN and ribavirin in cirrhotic patients infected with HCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility criteria

This review included all the studies published in English prior to December 2011 that evaluated SAEs in cirrhotic patients infected with HCV and treated with SOC therapy: PegIFN alpha 2a (dosage: 135-180 μg/wk) or PegIFN alpha 2b (dosage: 1 or 1.5 μg/kg per week) and ribavirin (dosage range: 800-1200 mg/d). Patients with genotype 1 + 4 underwent treatment for 48 wk, whereas those with genotypes 2 + 3 were treated for 24 wk. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was made either by liver biopsy or by clinical, ultrasonographic, endoscopic or laparoscopic signs of cirrhosis. Studies that included liver-transplanted patients or cases co-infected with hepatitis B virus or human immunodeficiency virus were excluded from the analysis.

Outcomes

The pre-specified primary outcome was the rate of SAEs (leading to treatment discontinuation) that occurred during treatment with PegIFN and ribavirin in cirrhotic patients infected with HCV.

The secondary outcomes were: description of SAEs; the possible relationships between SAE rates in cirrhotic patients and the following factors: decompensation of the disease (class Child-Pugh B or C), type of PegIFN (alpha 2a and alpha 2b) used in SOC therapy and HCV genotype; the proportion of patients in whom the medication dosage was reduced; and the SVR rate in cirrhotic patients, according to HCV genotype.

SVR was defined as undetectable HCV RNA in serum by real-time polymerase chain reaction 6 mo after discontinuation of therapy.

Data sources and searches

Relevant studies published prior to December 2011 were searched in PubMed, Medline, Lilacs, Scopus, Ovid, EMBASE, Cochrane and Medscape databases using the following keywords: liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis C, HCV, adverse events, sustained virological response, SVR.

Study selection and data collection

Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts for potential eligibility and the full texts for final eligibility. The following data were extracted: country of origin, year of publication, number of patients, age and weight of the patients, HCV genotype, the Child-Pugh class, the baseline treatment history (naive or previously treated), the treatment administered, the rate and description of SAEs that lead to treatment discontinuation, the proportion of patients in whom the doses of PegIFN and/or ribavirin were reduced, and the SVR rate according to HCV genotype.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis were carried out with the software package SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics (percentage, 95%CI) were calculated for each variable as appropriate. Standard binomial tests for differences in proportions were used to compare patient subgroups (“n” designates the total number of patients included in a particular subgroup). A P value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

RESULTS

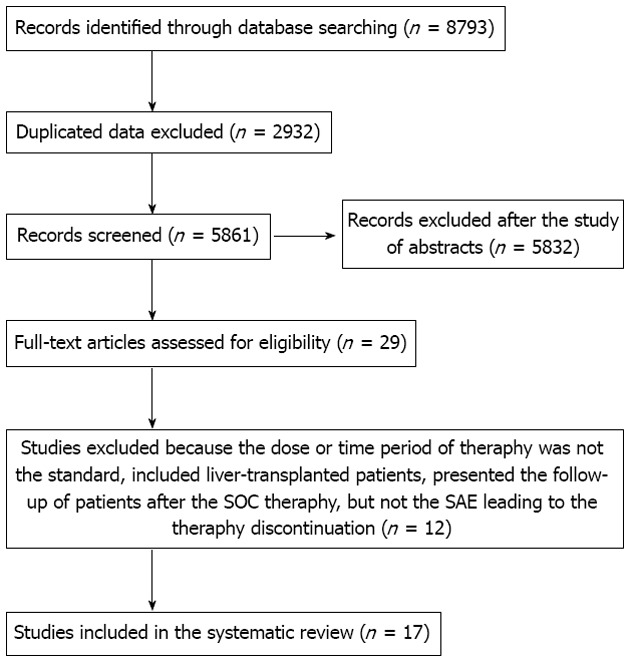

Of 8793 titles identified during the initial search, 8764 were excluded based on one of the following reasons: data published only in abstract, duplicated titles, data on cirrhotic patients not presented, the treatment regimen did not include PegIFN in combination with ribavirin or the same author had several similar articles, but with a different number of patients (we selected the article with the higher number of patients if we did not receive the information regarding the number of patients included in two or more studies from the author). Twelve articles which presented data on cirrhotic patients were excluded for the following reasons: the dosage or treatment duration with PegIFN and ribavirin were not standard; liver-transplanted patients were included; and the study presented the follow-up of patients after SOC therapy, but not the SAE leading to the therapy discontinuation. Finally, seventeen papers with 1133 patients with HCV liver cirrhosis were retrieved for analysis[12-28] (Figure 1). The main characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection of the studies. SOC: Standard of care; SAE: Severe adverse event.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic analysis

| Ref. | Study design | No. of patients | Age (yr) | Weight | HCV genotype | Baseline treatment history | Child-Pugh class | Treatment |

| Syed et al[12] | Retrospective cohort study | 104 | 52 ± 7.6 | 82 ± 15 kg (mean weight) | 1, 2, 3 | Naive and previously treated | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) or alpha 2b (1-1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (800-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Butt et al[13] | Prospective cohort study | 66 | 46.2 ± 10.1 | 22.3 ± 3.1 kg/m² (mean BMI) | 3 | Naive and previously treated | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) or alpha 2b (1 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (10-12 mg/kg per day) | ||||||||

| Giannini et al[14] | Retrospective cohort study | 85 | 56 ± 9 | Not specified | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Naive and previously treated | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) or alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (800-1200 mg/ d) | ||||||||

| Helbling et al[15] | Randomized controlled trial (standard doses vs low doses) | 64 | 47 (median age) | 74 kg (median weight) | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Naive | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) |

| Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/ d) | ||||||||

| Iacobellis et al[16] | Prospective cohort study | 94 | Not specified | Not specified | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Naive | B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (800-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Roffi et al[17] | Randomized controlled trial (pegylated interferon vs IFN standard) | 57 | 56 (median age) | 75 kg (median weight) | 1, 2, 3 | Naive | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (800-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Sood et al[18] | Retrospective cohort study | 28 | 48.3 ± 7 | 73.9 ± 11.2 kg (mean weight) | 3 (25/28 patients) and not specified for the other patients | Naive | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (10-12 mg/kg per day) | ||||||||

| Tekin et al[19] | Cohort study | 20 | 54.2 ± 5.9 | Not specified | 1 | Not specified | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (135 μg/wk) |

| Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Moreno Planas et al[20] | Cohort study | 12 | 52 ± 8 | Not specified | 1, 3 | Naive and previously treated | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (10.6 mg/kg per day) | ||||||||

| Di Marco et al[21] | Randomized controlled trial (pegylated interferon alpha 2B + ribavirin vs pegylated interferon alpha 2b) | 52 | 57 ± 6.6 | 71 ± 10.1 kg (mean weight) | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Naive and previously treated | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (800 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Höroldt et al[22] | Retrospective cohort study | 61 | Not specified | Not specified | 1, 2, 3 | Naive | A, B | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a or alpha 2b + ribavirin |

| Bruno et al[23] | Randomized study | 106 | Not specified | Not specified | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Naive | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) |

| Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Floreani et al[24] | Prospective cohort study | 87 | 55.7 ± 9.1 | 25.3 ± 3.1 kg/m² (mean BMI) | 1, 2, 3 | Naive | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (80-100 μg/wk) |

| Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Annicchiarico et al[25] | Prospective cohort study | 15 | 51.5 | Not specified | 1, 2, 3 | Naive and previously treated | B, C | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (800-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Aghemo et al[26] | Prospective cohort study | 106 | 57 ± 9.3 | 72.5 ± 11.8 kg (mean weight) | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Naive | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| Ribavirin (≥ 10.6 mg/kg per day) | ||||||||

| Kim et al[27] | Cohort study | 86 | 56.4 ± 9.6 | Not specified | 1 and non-1 | Not specified | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| or Pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) | ||||||||

| Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Reiberger et al[28] | Prospective cohort study | 90 | 51 ± 8 | 26.6 ± 5 kg/m² (mean BMI) | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Not specified | A | Pegylated interferon alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) |

| or pegylated interferon alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) | ||||||||

| Ribavirin (1000-1200 mg/d) |

HCV: Hepatitis C virus; BMI: Body mass index; IFN: Interferon.

In 165/1133 patients (14.5%), the antiviral treatment was stopped early due to SAEs. In 116/165 patients (70.3%), detailed information regarding the SAEs was presented. The most common SAEs leading to premature discontinuation of antiviral treatment in HCV cirrhotic patients were: severe thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia: n = 27 (23.2%); psychiatric disorders: n = 18 (15.5%); decompensation of liver cirrhosis: n = 14 (12.1%); and severe anemia: n = 13 (11.2%) (Table 2). The mortality rate in the cohort was 0.3% (4/1133 patients). The causes of death in the four patients were: severe sepsis, decompensation of heart disease, hepatocellular carcinoma and severe hepatic failure (this patient died 3 wk after stopping the treatment due to decompensation of liver cirrhosis).

Table 2.

Description of severe adverse event leading to premature discontinuation of antiviral treatment in hepatitis C virus cirrhotic patients (%)

| Name of severe adverse event | No. of patient discontinuities |

| Severe thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia | 27 (23.2) |

| Psychiatric disorders (depression, psychosis, confusion, lethargy) | 18 (15.5) |

| Decompensation of liver cirrhosis (ascites with or without spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; jaundice; hepatic encephalopathy) | 14 (12.1) |

| Severe anemia | 13 (11.2) |

| Occurrence of malignancies | 6 (5.1) - 4 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, 1 case of tongue carcinoma and 1 case of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma recurrence |

| Allergic reactions to medication | 5 (4.3) |

| Severe infections | 5 (4.3) |

| Severe fatigue | 5 (4.3) - in 2 cases accompanied also by “flu-like” syndrome |

| Neurological disorders (stroke, polyneuropathy, hemiparesthesia) | 5 (4.3) |

| Heart disease (heart failure or acute coronary syndrome) | 3 (2.5) |

| Endocrinology disorders | 3 (2.5) |

| Diabetes decompensation | 2 (1.7) |

| Persistent fever | 2 (1.7) |

| Severe denutrition | 2 (1.7) |

| Aminotransferases flare | 1 (0.8) |

| Severe decrease of vision | 1 (0.8) |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 (0.8) - the cause of bleeding was not specified |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 (0.8) |

| Severe flare of psoriasis | 1 (0.8) |

Fifteen studies[12-24,27,28], including 154 patients in whom the antiviral treatment was stopped because of SAEs, presented information regarding the incidence of hematological SAEs. In 49/154 patients (31.8%), the antiviral treatment with PegIFN and ribavirin was stopped as result of severe anemia, thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia.

From ten studies[12,15-17,23-28], we extracted data regarding the SAEs leading to antiviral treatment discontinuation according to the Child-Pugh class. The SAEs rate was significantly higher in patients with Child-Pugh class B and C (n = 109) vs those with Child-Pugh class A (n = 700): 22% vs 11.4%, P = 0.003.

From eleven studies[15-21,23-26], we extracted data regarding the SAEs rate according to the type of PegIFN used in combination with ribavirin for treatment. The SAEs rate was similar for PegIFN alpha 2a (n = 190) and PegIFN alpha 2b (n = 451): 14.2% vs 13.7%, P = 0.96.

We were able to extract data regarding the rate of SAEs leading to early treatment discontinuation according to the HCV genotype from only three studies[13,18,29]. The SAEs rate was significantly higher in patients with genotype 1 (n = 20) vs those with genotype 3 (n = 94): 30% vs 8.5%, P = 0.02.

Five studies[13,15,16,18,25] presented data regarding the number of patients in whom the doses of PegIFN and/or ribavirin were reduced. From a total of 267 patients, the dosage for either drug was reduced in 87 (32.5%).

Eight studies[14,17,19,20,22,26-28] presented separately the number of patients in which the doses of antiviral medication were reduced: in 107/517 patients (20.6%) for PegIFN and for ribavirin in 141/517 patients (27.2%).

The overall SVR rate in the seventeen studies included in this systematic review was 37% (95%CI: 33.5-43.1). SVR rates were significantly higher in patients with genotype 2 + 3 (n = 495) compared to those with genotype 1 + 4 (n = 570): 56.5% (95%CI: 51.1-63.2) vs 20.5% (95%CI: 17.9-24.8), P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Patients with HCV liver cirrhosis are a category of subjects difficult to treat due to the high risk of complications and the relatively low SVR rates. This systematic review summarizes and analyses the available data on the rates of SAEs leading to antiviral therapy discontinuation in cirrhotic patients infected with HCV. In 14.5% of the patients, treatment was discontinued due to SAEs, the most common of which were hematological disorders.

The proportion of cirrhotic patients presented in this systematic review in which the treatment was discontinued due to SAEs was higher than the proportion of patients with all stages of fibrosis in whom the treatment was discontinued due to SAEs presented in others studies. For example, in the study by Fried et al[29], only 32/453 patients (7%) discontinued their antiviral treatment due to SAEs. In the IDEAL study[7], 98/1016 patients (9.6%) treated with low doses of PegIFN alpha 2b (1 μg/kg per week) and ribavirin, 129/1019 patients (12.7%) treated with standard doses of PegIFN alpha 2b (1.5 μg/kg per week) and ribavirin and 135/1035 patients (13%) treated with standard doses of PegIFN alpha 2a (180 μg/wk) and ribavirin, had to discontinue their treatment as a result of SAEs developed during antiviral therapy.

In the present review, dose reduction of PegIFN was needed in 20.6% of patients and of ribavirin in 27.2%. These percentages were also higher than those presented in studies that included patients with all stages of fibrosis. In the study by Fried et al[29], the dose of PegIFN was reduced in 11% of patients and of ribavirin in 21%. In the IDEAL study[7], the dose of PegIFN was reduced in 6.9% of patients treated with low doses of PegIFN alpha 2b, in 10.1% of patients treated with standard doses of PegIFN alpha 2b and in 11.8% treated with standard doses of PegIFN alpha 2a. The dose of ribavirin was reduced in 16.7%, 18.4% and 17.4% of patients, respectively, included in the three arms of the IDEAL study.

In our review, the proportion of patients in whom the treatment had to be discontinued due to SAEs was significantly higher in patients with Child-Pugh class B and C vs those with Child-Pugh class A: 22% vs 11.4% (P = 0.003). The results are similar to those published in a review by Vezali et al[30], in which 20% of patients with decompensated liver disease and 12% with compensated cirrhosis needed to discontinue their therapy as result of SAEs. The proportion of drug discontinuation due to SAEs in cirrhotic patients with compensated liver disease vs those with less advanced liver disease was similar: 12% vs 13%. But the review by Vezali et al[30] also included decompensated cirrhotic patients treated with small doses of PegIFN[31], patients treated for a short period of time before or after liver transplantation[32,33], and patients with compensated liver cirrhosis treated only with PegIFN[34], while in our review, we included only cirrhotic patients in whom the dosage and the duration of therapy was standard.

The data analyzed in the present review showed a similar discontinuation rate due to SAEs in cirrhotic patients treated with PegIFN alpha 2a vs those treated with PegIFN alpha 2b (both in combination with ribavirin), similar to those obtained in the IDEAL study[7] (which included patients with all stages of fibrosis).

The discontinuation rate was significantly higher in patients with genotype 1 vs those with genotype 3, but this data could only be extracted from 3 studies. Also, in the only study which included genotype 1 patients[19], the majority of them were Child-Pugh class B (70%), while in one of the two studies which included only genotype 3 patients[15], most were Child-Pugh class A (92.4%). In the other study which includes only genotype 3 patients[18], data regarding the distribution of patients according to the Child-Pugh class is not presented. However, the discontinuation rate due to SAEs is probably higher in patients with genotype 1 + 4 than in those with genotype 2 + 3, in relationship to the longer period of time in which the patients could maintain the full dosing of antiviral medication. For example, in the study of Bruno et al[23], 86% of patients with genotype 2 + 3 maintained the full dosing and duration of therapy for PegIFN and 85% for ribavirin, while only 65% of patients with genotype 1 + 4 could maintain the full dosing of PegIFN and 56% for ribavirin. Another explanation is the longer duration of therapy for patients with genotype 1 + 4 (48 wk vs 24 wk).

Despite the low rate of SVR (especially in genotype 1 + 4), as well as the higher percentage of patients in whom the treatment is discontinued or the medication doses are reduced, Saab et al[35] demonstrated (using a Markov model) that treatment of patients with HCV genotype 1 liver cirrhosis (especially compensated) is cost effective. The study included approximately 4000 subjects followed over 17 years. Compared to the no-antiviral treatment strategy, treatment during compensated cirrhosis increased quality-adjusted life years by 0.950 and saved 55 314 dollars, while treatment during decompensated cirrhosis increased quality-adjusted life years by 0.044 and saved 5511 dollars. Also, treatment of patients with compensated cirrhosis resulted in 119 fewer deaths, 54 fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and 66 fewer transplants compared to the no-treatment strategy.

In recent years, several studies have used triple therapy (SOC therapy + direct antiviral agents) in patients with HCV genotype 1 infection; the most utilized direct antiviral agents are Telaprevir and Boceprevir[36-39]. This therapy could become the SOC in a short time.

There are few data regarding discontinuation rates of triple therapy as result of SAEs in cirrhotic patients. Only the RESPOND-2 trial[36] presented this kind of data. The percentage of patients in whom the antiviral therapy was discontinued due to SAEs was similar in SOC therapy vs triple therapy: 10% vs 15.3% (P = 0.93). Also, the proportion of patients in whom the doses had to be reduced was similar: 30% vs 33.3% (P = 0.85). But it should be noted that the number of cirrhotic patients was quite small: 10 patients treated with SOC therapy and 39 patients treated with triple therapy. If we consider all patients included in the RESPOND-2 trial[36], the percentage of patients in whom the treatment was stopped because of SAEs was much higher in patients treated with triple therapy than in those treated with SOC therapy: 8% and 12% (in the two arms which included patients treated with Boceprevir) vs 2%. Also, the proportion of patients in whom medication doses were reduced was higher in patients treated with triple therapy: 29% and 33% (in the two arms which included patients treated with Boceprevir) vs 14% (SOC therapy).

It is a known fact that one of the most common adverse events of Boceprevir treatment is anemia. In the SPRINT-2 trial[37], the proportion of patients in whom medication doses were reduced was much higher in patients treated with triple therapy vs those treated with SOC therapy: 21% vs 13%. It will be interesting to see the effect of triple therapy using Boceprevir as a direct antiviral agent in a large cohort of cirrhotic patients, knowing that SOC therapy needed to be discontinued due to severe hematological adverse events in 31.8% of patients in the present review. It should also be noted that erythropoietin was administered to correct anemia in the Boceprevir trials, while it was specified that the use of erythropoietin was allowed in only 5/17 of the studies included in the present review[12-14,16,18].

Also, the discontinuation rate as a result of SAEs was much higher in patients treated with triple therapy in the studies in which Telaprevir was used as a direct antiviral agent. In the REALIZE trial[38], the discontinuation rate due to SAEs was 3% for SOC therapy and 11% and 15%, respectively, in the two arms which used Telaprevir. In the PROVE 3 trial[39], 4% of patients treated by SOC therapy discontinued treatment as a result of SAEs, compared to 9%-26% of patients in whom Telaprevir was used as a direct antiviral agent.

In conclusion, 14.5% of cirrhotic patients treated with PegIFN and ribavirin needed early discontinuation of therapy because of SAEs, the most common cause being hematological disorders, while in approximately 30% of patients, the medication doses were reduced. Most likely these percentages will increase in the future with the use of direct antiviral agents. The overall SVR rate in cirrhotic patients included in this review was 37%; however, it was much lower in cases infected with HCV genotype 1 + 4 (20.5%).

COMMENTS

Background

Patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) liver cirrhosis are difficult to treat. One of the reasons for this is the rate of severe adverse events (SAEs).

Research frontiers

In the last 10 years, pegylated interferon (PegIFN) and ribavirin have become the standard of care treatment in chronic HCV infection. In patients with liver cirrhosis, the sustained virological response (SVR) rate is even lower, at approximately 20% in genotype 1 or 4 infection and 55% in patients with genotype 2 or 3 infection. Also, cirrhotic patients have a reduced tolerance to therapy but the risk of further complications is smaller in patients who achieve SVR.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This systematic review aims to identify and analyze the SAEs that lead to treatment discontinuation during treatment with PegIFN and ribavirin in cirrhotic patients infected with HCV.

Peer review

The manuscript is very well written and makes clear conclusions about the risks of anti-viral treatment in patients with HCV related cirrhosis.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer Balaban YH S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C. Report of a WHO Consultation organized in collaboration with the Viral Hepatitis Prevention Board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:35–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2436–2441. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fattovich G, Giustina G, Degos F, Tremolada F, Diodati G, Almasio P, Nevens F, Solinas A, Mura D, Brouwer JT, et al. Morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type C: a retrospective follow-up study of 384 patients. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:463–472. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Natural history of hepatitis C. Clin Liver Dis. 2005;9:383–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, Muir AJ, Galler GW, McCone J, Nyberg LM, Lee WM, Ghalib RH, Schiff ER, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580–593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bota S, Sporea I, Popescu A, Sirli R, Neghina AM, Danila M, Strain M. Response to standard of care antiviral treatment in patients with HCV liver cirrhosis - a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1147–1171. doi: 10.1002/hep.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright TL. Treatment of patients with hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;36:S185–S194. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veldt BJ, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, Reichen J, Hofmann WP, Zeuzem S, Manns MP, Hansen BE, Schalm SW, Janssen HL. Sustained virologic response and clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:677–684. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syed E, Rahbin N, Weiland O, Carlsson T, Oksanen A, Birk M, Davidsdottir L, Hagen K, Hultcrantz R, Aleman S. Pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in patients with Child-Pugh Class A liver cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1378–1386. doi: 10.1080/00365520802245395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butt AS, Mumtaz K, Aqeel I, Shah HA, Hamid S, Jafri W. Sustained virological response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin in patients with genotype 3 HCV cirrhosis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009;30:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannini EG, Basso M, Savarino V, Picciotto A. Predictive value of on-treatment response during full-dose antiviral therapy of patients with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis and portal hypertension. J Intern Med. 2009;266:537–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helbling B, Jochum W, Stamenic I, Knöpfli M, Cerny A, Borovicka J, Gonvers JJ, Wilhelmi M, Dinges S, Müllhaupt B, et al. HCV-related advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis: randomized controlled trial of pegylated interferon alpha-2a and ribavirin. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:762–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iacobellis A, Siciliano M, Annicchiarico BE, Valvano MR, Niro GA, Accadia L, Caruso N, Bombardieri G, Andriulli A. Sustained virological responses following standard anti-viral therapy in decompensated HCV-infected cirrhotic patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:146–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roffi L, Colloredo G, Pioltelli P, Bellati G, Pozzpi M, Parravicini P, Bellia V, Del Poggio P, Fornaciari G, Ceriani R, et al. Pegylated interferon-alpha2b plus ribavirin: an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment regimen for patients with hepatitis C virus related histologically proven cirrhosis. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:663–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood A, Midha V, Sood N, Bansal M. Pegylated interferon alfa 2b and oral ribavirin in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tekin F, Gunsar F, Karasu Z, Akarca U, Ersoz G. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pegylated-interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin in HCV-related decompensated cirrhotics. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1081–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno Planas JM, Rubio González E, Boullosa Graña E, Fernández Ruiz M, Jiménez Garrido M, Lucena de la Poza JL, Martínez Arrieta F, Molina Miliani C, Sánchez Turrión V, Cuervas-Mons Martínez V. Effectiveness of pegylated interferon and ribavirin in patients with liver HCV cirrhosis. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1482–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Marco V, Almasio PL, Ferraro D, Calvaruso V, Alaimo G, Peralta S, Di Stefano R, Craxì A. Peg-interferon alone or combined with ribavirin in HCV cirrhosis with portal hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2007;47:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Höroldt B, Haydon G, O’Donnell K, Dudley T, Nightingale P, Mutimer D. Results of combination treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C infection. Liver Int. 2006;26:650–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruno S, Shiffman ML, Roberts SK, Gane EJ, Messinger D, Hadziyannis SJ, Marcellin P. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD) plus ribavirin in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:388–397. doi: 10.1002/hep.23340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floreani A, Baldo V, Rizzotto ER, Carderi I, Baldovin T, Minola E. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin for naive patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:734–737. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318046ea75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annicchiarico BE, Siciliano M, Avolio AW, Caracciolo G, Gasbarrini A, Agnes S, Castagneto M. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1918–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aghemo A, Rumi MG, Monico S, Prati GM, D’Ambrosio R, Donato MF, Colombo M. The pattern of pegylated interferon-alpha2b and ribavirin treatment failure in cirrhotic patients depends on hepatitis C virus genotype. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim KH, Jang BK, Chung WJ, Hwang JS, Kweon YO, Tak WY, Lee HJ, Lee CH, Suh JI. Peginterferon alpha and ribavirin combination therapy in patients with hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17:220–225. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2011.17.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiberger T, Rutter K, Ferlitsch A, Payer BA, Hofer H, Beinhardt S, Kundi M, Ferenci P, Gangl A, Trauner M, et al. Portal pressure predicts outcome and safety of antiviral therapy in cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:602–608.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vezali E, Aghemo A, Colombo M. A review of the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in cirrhosis. Clin Ther. 2010;32:2117–2138. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(11)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crippin JS, McCashland T, Terrault N, Sheiner P, Charlton MR. A pilot study of the tolerability and efficacy of antiviral therapy in hepatitis C virus-infected patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:350–355. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.31748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrión JA, Martínez-Bauer E, Crespo G, Ramírez S, Pérez-del-Pulgar S, García-Valdecasas JC, Navasa M, Forns X. Antiviral therapy increases the risk of bacterial infections in HCV-infected cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation: A retrospective study. J Hepatol. 2009;50:719–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forns X, García-Retortillo M, Serrano T, Feliu A, Suarez F, de la Mata M, García-Valdecasas JC, Navasa M, Rimola A, Rodés J. Antiviral therapy of patients with decompensated cirrhosis to prevent recurrence of hepatitis C after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2003;39:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heathcote EJ, Shiffman ML, Cooksley WG, Dusheiko GM, Lee SS, Balart L, Reindollar R, Reddy RK, Wright TL, Lin A, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1673–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saab S, Hunt DR, Stone MA, McClune A, Tong MJ. Timing of hepatitis C antiviral therapy in patients with advanced liver disease: a decision analysis model. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:748–759. doi: 10.1002/lt.22072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Goodman ZD, Sings HL, Boparai N, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, Focaccia R, Younossi Z, Foster GR, Horban A, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, Afdhal NH, Heathcote EJ, Zeuzem S, Reesink HW, Garg J, et al. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1292–1303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]