Abstract

Nucleotide hydrolysis is essential for many aspects of cellular function. In the case of 3′,5′-bisphosphorylated nucleotides, mammals possess two related 3′-nucleotidases, Golgi-resident 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) phosphatase (gPAPP) and Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase 1 (Bpnt1). gPAPP and Bpnt1 localize to distinct subcellular compartments and are members of a conserved family of metal-dependent lithium-sensitive enzymes. Although recent studies have demonstrated the importance of gPAPP for proper skeletal development in mice and humans, the role of Bpnt1 in mammals remains largely unknown. Here we report that mice deficient for Bpnt1 do not exhibit skeletal defects but instead develop severe liver pathologies, including hypoproteinemia, hepatocellular damage, and in severe cases, frank whole-body edema and death. Accompanying these phenotypes, we observed tissue-specific elevations of the substrate PAP, up to 50-fold in liver, repressed translation, and aberrant nucleolar architecture. Remarkably, the phenotypes of the Bpnt1 knockout are rescued by generating a double mutant mouse deficient for both PAP synthesis and hydrolysis, consistent with a mechanism in which PAP accumulation is toxic to tissue function independent of sulfation. Overall, our study defines a role for Bpnt1 in mammalian physiology and provides mechanistic insights into the importance of sulfur assimilation and cytoplasmic PAP hydrolysis to normal liver function.

Keywords: ribosome biogenesis, nucleolus, phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate, exoribonuclease

The liver is an important hub for a diverse array of processes, including metabolism, detoxification, and protein production. To meet these demands, hepatocytes, the fundamental units of the liver that account for 70% of its weight, perform hundreds of different biochemical reactions. One component of hepatocellular function that is essential for numerous downstream physiological processes is the synthesis and export of more than 100 plasma proteins (1, 2). Albumin, which accounts for greater than 60% of the hepatically produced plasma protein content, transports hormones, fatty acids, metals, and xenobiotics throughout the body and provides roughly 75% of the vascular osmotic pressure (2). Because of its importance, mammals have developed multiple safeguards to maintain consistent serum albumin concentrations, and as a result, significant reductions in its abundance are generally only seen in chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis. Indeed, loss of oncotic pressure and concurrent presentation of edema is often indicative of liver failure (1).

The liver also provides the first layer of defense against cytotoxic agents through a number of biotransformation pathways (3, 4), one of which is mediated by the sulfotransferase (SULT) superfamily of enzymes that catalyzes the transfer of activated sulfur from the universal donor 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to acceptor molecules. PAPS is synthesized from inorganic sulfate through the successive sulfurylase and kinase activities of PAPS synthases, such as mammalian Papss2 (5–8), and although PAPS in metazoans is consumed exclusively by SULTs, its uses diverge widely in other kingdoms of life (8). Regardless of the acceptor molecule, PAPS-using reactions generate the byproduct 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate (PAP) (5–7), which is degraded to 5′-AMP by a family of enzymes known as 3′-nucleotidases (8).

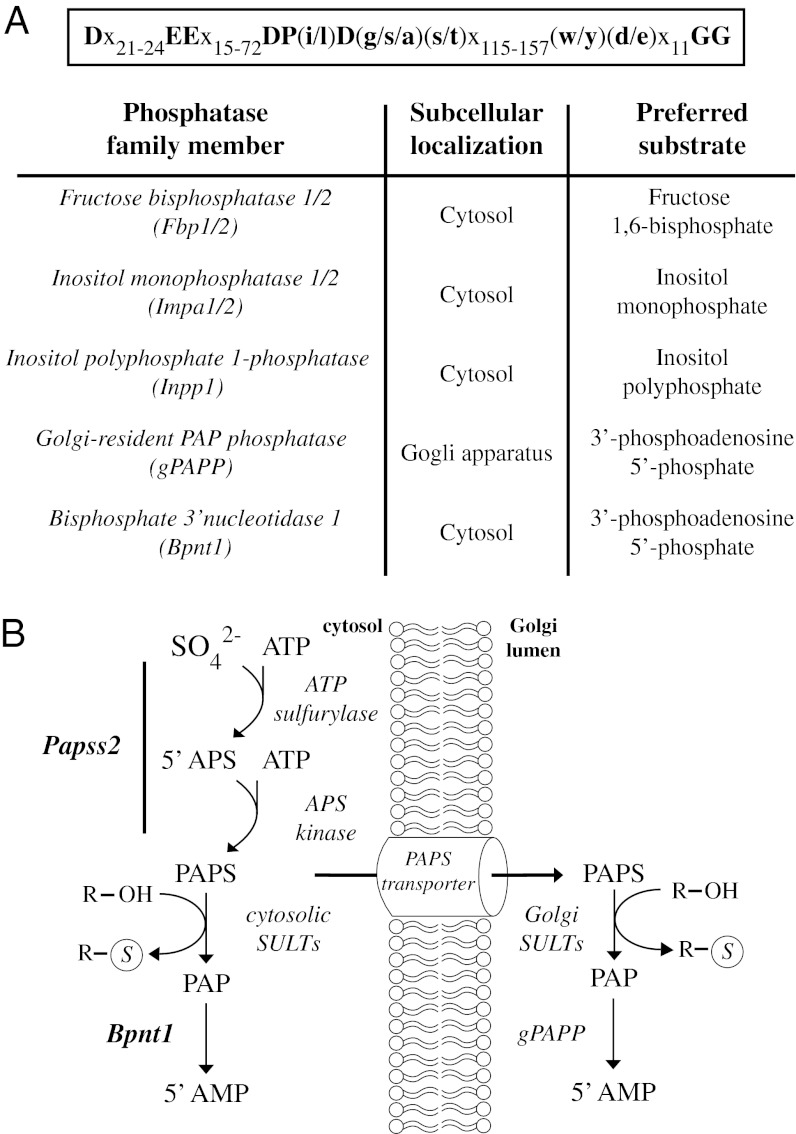

Mammalian genomes encode two 3′-nucleotidases, the recently characterized Golgi-resident PAP phosphatase (gPAPP) and Bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase 1 (Bpnt1), which localize to the Golgi lumen and cytoplasm, respectively (Fig. 1B) (8–11). gPAPP and Bpnt1 are members of a family of small-molecule phosphatases whose activities are both dependent on divalent cations and inhibited by lithium (8). The family comprises seven mammalian gene products: fructose bisphosphatase 1 and 2, inositol monophosphatase 1 and 2, inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase, gPAPP, and Bpnt1 (Fig. 1A). Although the members display limited overall sequence similarity, their shared properties are defined by a common structural core and the catalytic motif, D-Xn-EE-Xn-DP(i/l)D(s/g/a)T-Xn-WDXn-11GG (12).

Fig. 1.

A lithium-sensitive family of small-molecule phosphatases and the sulfate assimilation pathway. (A) The Mus Musculus family of metal-dependent/lithium-sensitive phosphomonoesterases and the consensus core motif that defines the family. (B) Schematic of the sulfate assimilation pathway intermediates. Bpnt1 and gPAPP hydrolyze the 3′ phosphate from the sulfation byproduct PAP in the cytoplasm and Golgi lumen, respectively. In mice, Papps2 encodes a dual functional enzyme with both ATP sulfurylase and APS kinase activities that synthesize PAPS from sulfate and ATP.

Although Bpnt1 and gPAPP share a common substrate, their localization to distinct cellular compartments suggests that they play unique roles in the cell. gPAPP, whose evolution parallels the appearance of metazoan-specific Golgi-localized sulfation, is essential for normal development. Its inactivation in mice results in pulmonary insufficiency, joint defects, and impaired skeletal development due to inadequate chondroitin and heparan sulfation (11, 13). In addition, the identification of a phenotypically related human skeletal disease resulting from mutations in gPAPP confirms that Golgi-resident 3′-nucleotidase activity is essential for sulfation-dependent processes such as cartilage formation and long bone growth (14). Conversely, functional studies in bacteria and yeast have implicated the more ancient cytosolic 3′-nucleotidase Bpnt1 in numerous sulfation-independent processes, including salt tolerance and methionine biosynthesis (15–23). Thus, although it is clear that gPAPP is essential for proper Golgi-mediated sulfation, the role of Bpnt1 in mammals and its potential connection to cytosolic sulfation remains unclear.

Here we report the generation and analysis of Bpnt1 global knockout mice. Loss of cytoplasmic 3′-nulceotidase function results in markedly distinct phenotypes compared with those observed in gPAPP- or SULT-deficient animals. Our data provide an unanticipated genetic basis for pathologies that in severe cases lead to liver failure, whole-body edema, and death and whose etiology seems to be independent of sulfation. Additionally, we demonstrate a genetic strategy to completely reverse the physiological defects in Bpnt1-deficient mice, which may inspire pharmacological approaches to overcoming 3′-nucleotidase deficiency. Our study provides insights into the role of Bpnt1 in mammalian physiology and illuminates the unique contributions of compartment-specific 3′-nucleotide hydrolysis.

Results

Bpnt1 Null Mice Develop Edema as a Result of Liver Dysfunction.

To further our understanding of Bpnt1’s role in mammals we used homologous recombination to generate global knockout mice (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Heterozygous and homozygous null animals were viable and developed according to expected Mendelian distributions. Analysis of tissues from homozygous null animals by Western blot revealed a complete absence of detectable Bpnt1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). At birth and through early development, homozygous null mice appear grossly identical to their wild-type and heterozygote littermates, and we have seen no evidence of haploinsufficiency in Bpnt1 heterozygote animals throughout adulthood. However, most prominently, by 45 d of age on average, homozygous null mice develop a 45% penetrant lethal full-body edema (Fig. 2A).

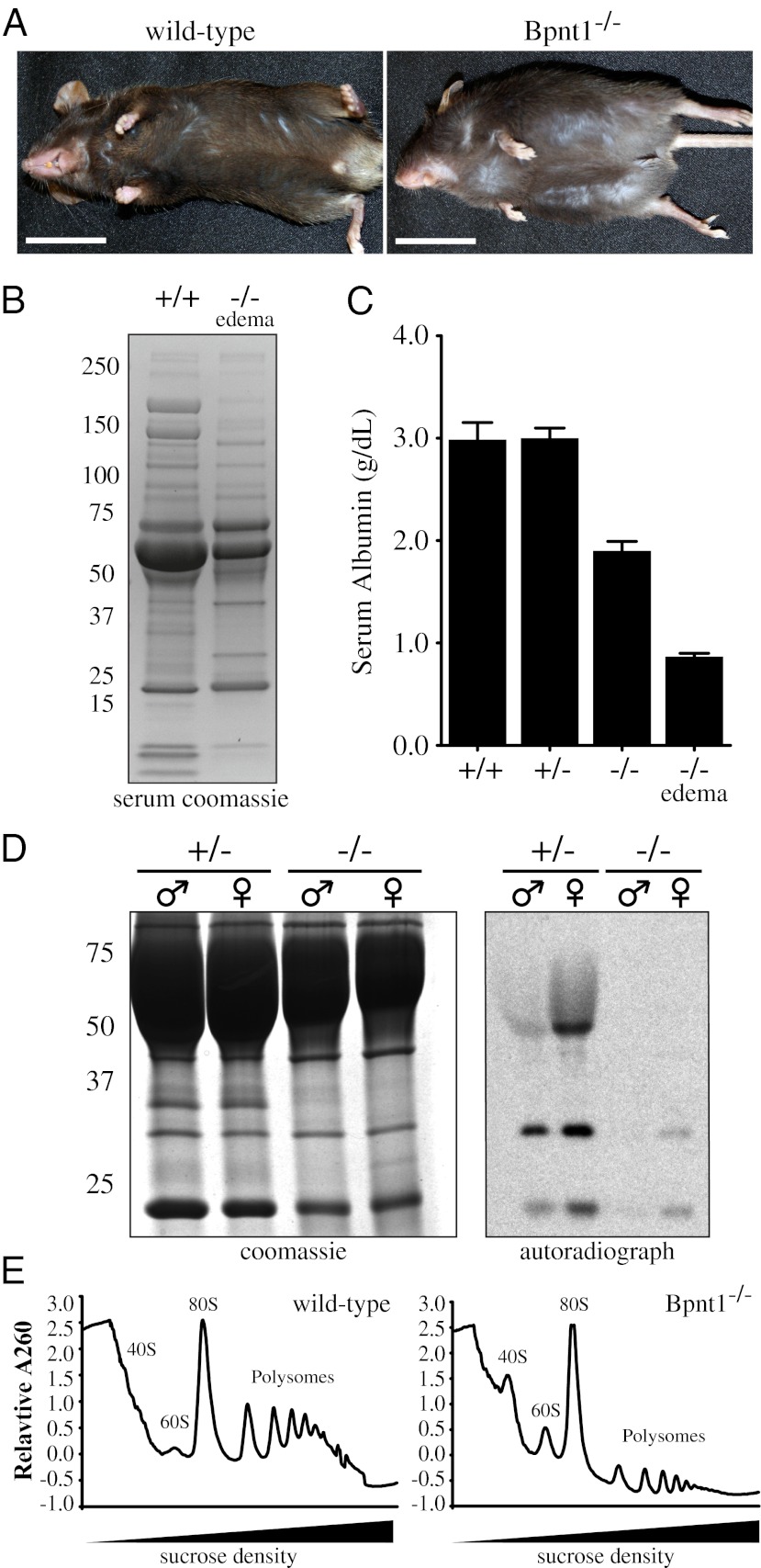

Fig. 2.

Hypoproteinemia and repressed translation in Bpnt1 null animals. (A) Photograph of Bpnt1 wild-type (Left) and homozygous null (Right) littermates illustrating the full-body edema. (Scale bar, 2 cm.) (B) Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE of Bpnt1 wild-type and knockout total serum protein. (C) Quantification of serum albumin in wild-type, heterozygote, and knockout mice. Values represent mean ± SEM. (D) (Right) SDS/PAGE of 2 μL of 3H-leucine-labeled serum, dried and visualized by fluorography. (Left) Identical gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (E) Polysome profiles from wild-type and knockout liver tissue. Note the significantly lower levels of polysomes in Bpnt1 null livers.

One cause of whole-body edema is hypoproteinemia as a result of inadequate hepatic protein export. To investigate this possibility, we analyzed serum from wild-type and Bpnt1 null mice by SDS/PAGE and clinical chemistries. Strikingly, Bpnt1 null mice showed significantly lower levels of many serum proteins compared with wild types (Fig. 2B). One protein we found to be markedly repressed, albumin, normally constitutes greater than 60% of the total serum protein content and provides the principle component of the osmotic pressure necessary to maintain fluid inside the vasculature. Because of its importance, the liver maintains tight control over its serum concentration, with normal values in mice ranging from 2.7 to 3.3 g/dL. Compared with wild-type animals, Bpnt1 null mice showed a 36% reduction (1.9 vs. 3.0 g/dL) in serum albumin, whereas mice presenting with edema had further repressed albumin concentrations of 0.9 g/dL (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Table S1). In addition, serum clinical chemistries revealed that total cholesterol in Bpnt1 null animals was significantly lower than in wild types (69.2 vs. 188.2 mg/dL) and that levels of the liver enzymes ALT, AST, and ALKP (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase) were elevated, indicative of substantial hepatocellular damage (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A and Table S1).

To investigate whether the hypoproteinemia and edema in Bpnt1 null mice might be a direct result of insufficient hepatic protein production, we used in vivo radioactive metabolic labeling to measure the rates of serum protein synthesis. After a pulse of i.p.-injected 3H-leucine in rats and mice, radiolabeled albumin begins to appear in the blood within 30 min (24). Indeed, we found that after 30 min, Bpnt1 null mice incorporated dramatically less radioactivity into newly synthesized albumin (Fig. 2D, top band). In addition to decreased incorporation of 3H-leucine into albumin, we detected two other bands that showed slower kinetics of production in knockout animals, which we identified by mass spectrometry as apolipoproteins E and A1, two of the major protein components of de novo hepatically synthesized lipoproteins, such as LDL (Fig. 2D, lower bands).

To address whether the slower serum protein production was due to a defect in hepatic translation, we examined polysome profiles of wild-type and Bpnt1 null livers. In general, mRNAs undergoing more active translation are populated by a greater number of ribosomes than less actively translated messages and therefore will occupy denser sucrose fractions after ultracentrifugation. Thus, comparing the relative quantities of ribosomes in light and dense fractions provides insight into the global translational status of the cell. Relative to wild type, ribosomes from Bpnt1 null livers were greatly enriched in the light sucrose fractions containing individual subunits and 80S monosomes and less abundant in the more dense polysome-containing fractions (Fig. 2E).

Bpnt1 Null Mice Have Aberrant Hepatocellular Morphology.

Given the striking deficiencies in liver function, we sought to understand what underlying hepatocellular defects were leading to hypoproteinemia, edema, and death. Grossly, Bpnt1 null livers appeared pale and enlarged (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), whereas H&E staining revealed striking alterations to hepatocellular morphology, including hypertrophied nuclei and large abnormal subnuclear structures (Fig. 3A). Importantly, the abnormalities were not localized to a particular liver lobule or zone but instead were evenly distributed throughout the entire liver. The homogenous pattern of expression was distinct from most models of liver injury, which tend to affect either periportal or perivenous zones disproportionately, and suggested that the primary defect was intrinsic to hepatocytes (25).

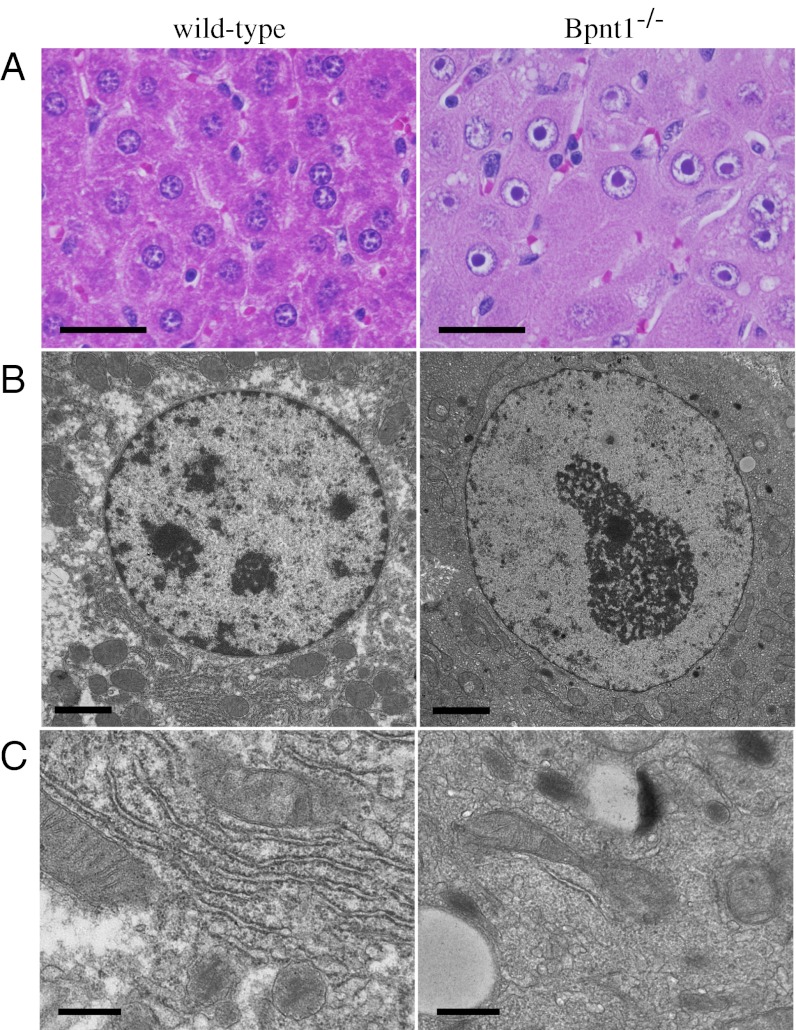

Fig. 3.

Aberrant hepatocellular morphology in Bpnt1 null animals. (A) Five-micrometer H&E-stained liver sections from wild-type and knockout mice demonstrating the hypertrophied nuclei and condensed nucleoli. (Scale bars, 20 μm.) (B and C) Transmission electron micrographs of wild-type and knockout hepatocytes. Note the absence of visible inner nuclear-membrane bound DNA and rough endoplasmic reticulum in knockouts. (Scale bars, 2 μm in B, 500 nm in C.)

Because mouse hepatocytes normally contain between three and five visible nucleoli within each nucleus, we wondered whether the structure might be a single condensed nucleolus. Indeed, indirect immunofluorescence for the nucleolar-resident proteins fibrillarin and B23 confirmed that the observed structures contained both dense fibrillar components and granular components, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Ultrastructural examination by transmission electron microscopy revealed that the nuclei contained dramatically less inner membrane-bound DNA and little detectable contiguous rough endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 3 B and C). In addition, we observed a number of changes to the cytoplasmic composition, including small irregular mitochondria, reduced glycogen, and abundant lipid droplets. Indeed, Oil Red O staining of frozen liver tissue demonstrated a striking quantity of accumulated neutral lipids distributed throughout the hepatocytes of Bpnt1 null mice that upon further analysis were found to contain cholesteryl esters and triglycerides, the lipids most abundant in hepatically produced lipoproteins such as LDL (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C).

Bpnt1 Null Livers Accumulate Bisphosphorylated Nucleotides.

Because Bpnt1 plays an important role in sulfur assimilation pathways, we next examined nucleotide levels in TCA/ethyl-ether extracts obtained from normal and mutant liver. An HPLC-based method resolved mono-, di-, and triphosphorylated nucleotides, and we observed that the levels of 5′ AMP, ADP, and ATP were not significantly altered in the wild-type compared with mutant samples (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the levels of bisphosphorylated nucleotides, PAP and PAPS, were dramatically elevated in the mutant liver (Fig. 4A). Although the levels of these molecules in normal samples were at or below the limit of detection for our assay, in knockout liver extracts we observed a clearly detectable significant peak of PAP and to a lesser extent PAPS (whose relative mass seemed to be 10-fold less than that of PAP) (Fig. 4A).

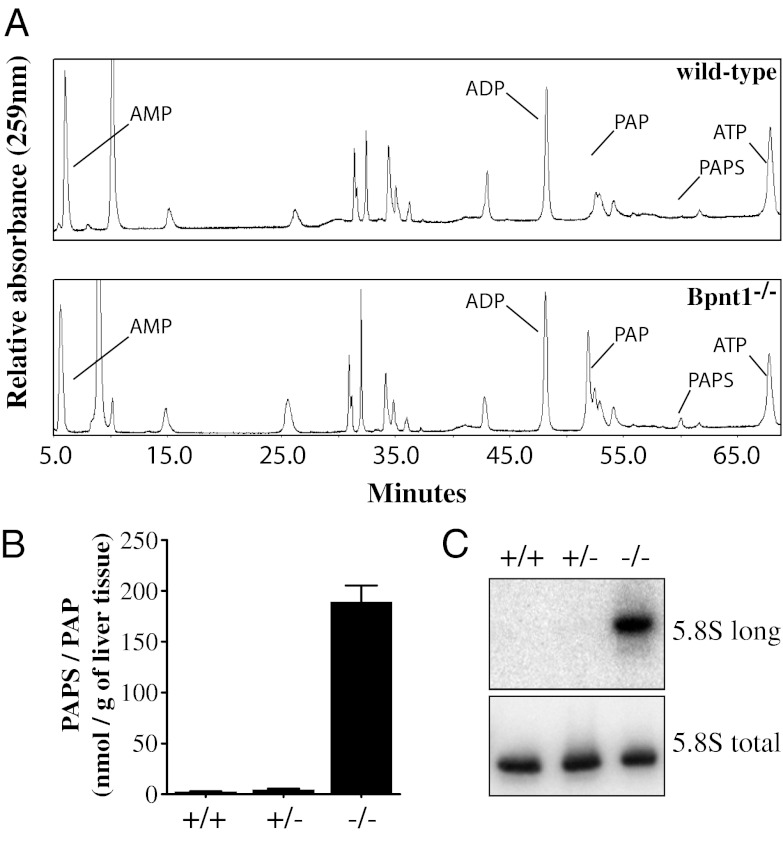

Fig. 4.

Accumulation of PAP and unprocessed ribosomal RNA. (A) Chromatogram of small-molecule extracts from wild-type and knockout liver tissue analyzed by SAX-HPLC-UV. Note the significant accumulation of PAP relative to PAPS. (B) Quantification of PAPS and PAP content in wild-type, heterozygote, and knockout livers as measured by enzymatic assay. Values represent mean ± SEM. (C) Accumulation of aberrant 5′-extended 5.8S rRNA subunits in knockout liver RNA as detected by Northern blot.

To further quantify changes in PAP, we used a simple colorimetric assay suitable for tissue analysis based in part on previously reported methodologies (26, 27). Briefly, small-molecule extracts from wild-type and knockout livers were isolated using boiling glycine. The extracts were then subjected to a PAP-dependent enzymatic assay in which the rate of color development is dependent on the combined concentration of PAPS. Strikingly, we found that Bpnt1 null livers contained roughly 30- to 50-fold as much PAP/PAPS as wild-type or heterozygote livers (Fig. 4B). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that aberrant accumulation of PAP, and not changes in 5′ AMP or other adenosine nucleotides, may account for the observed liver phenotypes.

Genetic Suppression of Physiological Defects in Bpnt1 Null Mice.

Given the known roles of both Golgi and cytoplasmically localized 3′-nucleotidases, we were interested in determining whether the liver failure was the result of defects in sulfation-dependent or -independent processes. In yeast deficient for Bpnt1, elevated PAP has been shown to inhibit the activity of Xrn2 (Rat1p), a conserved 5′-3′ exoribonuclease, and impair the enzyme’s ability to process the pre-5.8S ribosomal RNA subunit (28). Despite the significant evolutionary divergence between yeast and mammals, we wondered whether high levels of intracellular PAP might also inhibit murine ribosomal RNA processing. To examine this possibility, we isolated total RNA from wild-type, heterozygote, and Bpnt1 null livers and used Northern blotting to probe for both 5′-extended and total 5.8S rRNA subunits. Remarkably, only knockout livers had any detectable accumulation of 5′-extended 5.8S rRNA, confirming the presence of sulfation-independent PAP-sensitive pathways (Fig. 4C).

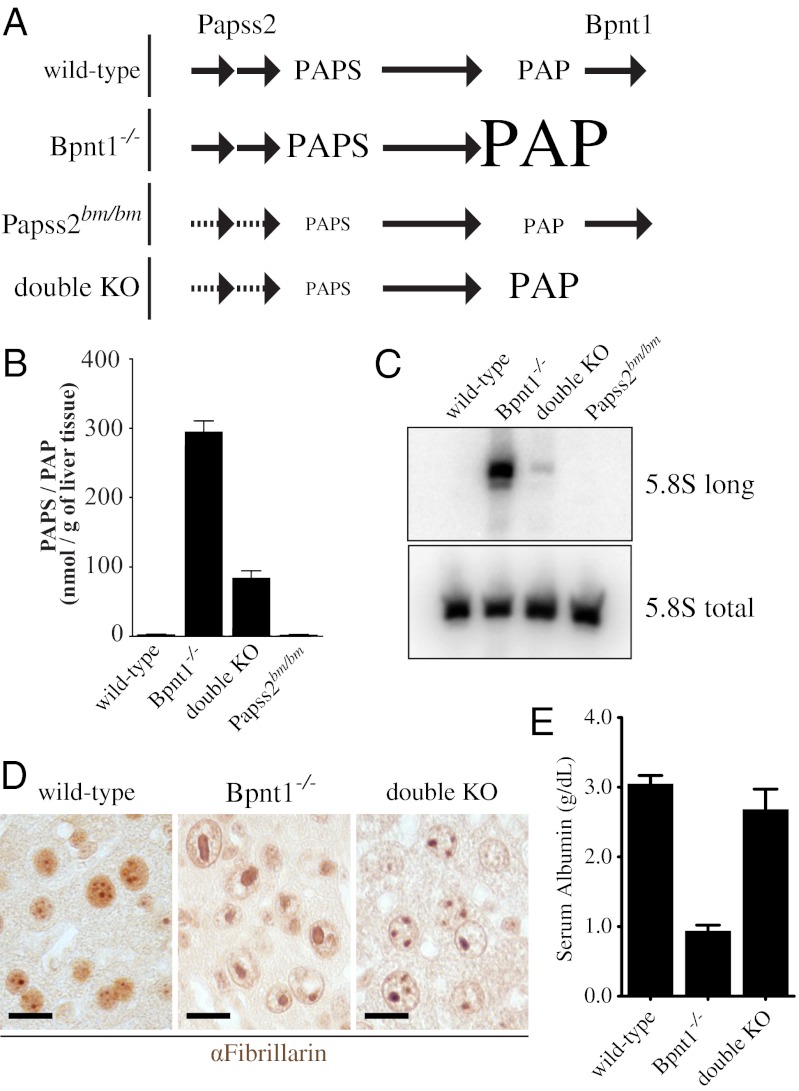

To further investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the observed hepatocellular toxicity, we used a genetic approach designed to distinguish between sulfation-dependent and -independent pathways. The Papss2bm/bm brachymorphic mouse mutant is compromised for PAPS synthesis (Fig. 1A) and as a result exhibits defects in sulfation-dependent processes (7, 29–31). We hypothesized that if the liver defects were the result of impaired sulfation then a double-knockout mouse (Papss2bm/bm Bpnt1−/−) may exacerbate the toxic phenotypes observed in Bpnt1−/− mutants. Conversely, if the accumulation of PAP results in the inhibition of targets outside of the sulfation axis, such as ribosomal RNA processing, then combining mutations may rescue the phenotypes because a loss of upstream bisphosphorylated nucleotide synthesis may neutralize the accumulation of PAP observed in the nucleotidase-deficient animal (modeled in Fig. 5A). To examine this, we crossed Bpnt1 mutant mice with the Papss2bm/bm brachymorphic animals. Compared with Bpnt1−/−Papss2+/+ littermates, double knockouts showed no signs of hepatocellular toxicity or whole-body edema. Further, we found that double-knockout livers had repressed levels of PAP and a corresponding suppression of unprocessed 5.8S rRNA (Fig. 5 B and C). Histologically, double-knockout hepatocytes appeared grossly normal, with fewer than 10% of nuclei containing visibly condensed nucleoli (Fig. 5D). In addition, double mutant mice exhibited rescued serum chemistries for liver damage markers and serum albumin, and no incidence of edema throughout adulthood (Fig. 5E and SI Appendix, Table S2). As a corollary, we performed identical experiments using gPAPP mice, whose phenotypes are the result of insufficient glycosaminoglycan sulfation (11). Significantly, we observed no rescue of the skeletal abnormalities or neonatal lethality by repressing global sulfation in gPAPP mutants (SI Appendix, Table S3). These experiments provide strong forward genetic evidence that gPAPP and Bpnt1 function through unique mechanisms and that loss of Bpnt1 induces toxicity through sulfation-independent pathways.

Fig. 5.

Rescue of hepatic insufficiencies by repressing bisphosphorylated nucleotide synthesis. (A) Schematic illustrating the production of PAPS, PAP, and 5′-AMP in wild-type, Bpnt1−/−, and double-knockout animals. Values represent mean ± SEM. (B) Quantification of combined PAPS and PAP levels in liver tissue as measured by enzymatic assay. Note the significant reduction in PAPS and PAP in double knockouts. (C) Northern blot of 5′-extended 5.8S rRNA subunits. Note that whereas double knockouts still contain detectable levels of unprocessed 5.8S, the quantity compared with Bpnt1−/− is greatly reduced. (D) Photographs of wild-type, Bpnt1−/−, and double-knockout liver tissue stained for nucleolar-resident fibrillarin by immunohistochemistry. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (E) Quantification of serum albumin levels in wild-type, Bpnt1−/−, and double-knockout animals. Values represent mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Our data illuminate an important role for the cytoplasmic 3′-nucleotidase Bpnt1 in normal liver function. Loss of Bpnt1 results in severe hepatic deficiencies and frequently leads to liver failure and death. These phenotypes are markedly distinct from the skeletal abnormalities we reported for Golgi 3′-nucleotidase gPAPP deficient mice and suggest that compartmentalization, or possibly differential tissue distribution, may account for the evolution of fundamentally unique roles for 3′-nucleotidases in cellular and organismal physiology. Overall, Bpnt1 null mice provide a unique model for studying cytoplasmic PAP metabolism, nucleolar dynamics, and liver disease and give insight into the biological roles of 3′-nucleotidases in mammals.

Mechanistically, the ability to rescue the defects of Bpnt1 null mice by concomitantly repressing bisphosphorylated nucleotide synthesis provides insight regarding how loss of cytoplasmic 3′-nucleotidase activity might lead to impaired hepatic function. Furthermore, the rescue of the effects of loss of 3′-nucleotidase activity by breeding to a Papss2 sulfation-deficient mouse provides strong genetic evidence arguing that the Bpnt1 mutant phenotypes observed are sulfation independent and occur as a result of the toxic accumulation of PAP and/or other potential substrates. In contrast to Bpnt1 null mice, the skeletal abnormalities and neonatal lethality that arise from inactivation of the Golgi-localized 3′-nucleotidase gPAPP are not rescued by repression of PAPS synthesis. The differential outcome bolsters our models in which the defects of gPAPP mutants are the direct result of impaired Golgi-mediated sulfation, whereas loss of Bpnt1 acts through a distinct sulfation-independent mechanism.

Although our genetic and biochemical data point to a model in which PAP accumulation leads to toxicity, we cannot formally rule out other possible Bpnt1 substrates. For example, Bpnt1 has been shown to hydrolyze other 3′-phosphorylated nucleotides in vitro, including 3′-phosphocytosine 5′-phosphate and 3′-phosphoguanosine 5′-phosphate, while also displaying activity against inositol phosphates, albeit with 1,000-fold reduced catalytic efficiency (10). Further, although Michaelis-Menten constants for PAPS hydrolysis have not been reported, competitive inhibition experiments have suggested that murine Bpnt1 can degrade PAP and PAPS with roughly equivalent catalytic efficiencies (10). Relative to wild type, Bpnt1 null livers contain elevated levels of PAP and PAPS; however, the 10-fold higher levels of PAP compared with PAPS leaves open the possibility that PAPS accumulation is a mass-action effect derived from PAP rather than a result of it being a bone fide substrate of Bpnt1. The failure to detect the accumulation of any other previously reported substrates is indicative that these molecules do not play a role in the phenotypes observed.

There are a number of potential cellular targets that may be influenced by the dramatic accumulation of PAP observed in hepatocytes. It is well established that PAP competes strongly with PAPS in vitro for binding to SULTs, leading to a nonproductive SULT/substrate/PAP complex (32, 33). However, because we are able to rescue the defects of Bpnt1 null mice by repressing PAPS synthesis, and thereby depleting the substrate of SULTs, it is unlikely that impaired sulfation is responsible for the liver failure. As mentioned previously, PAP has also been shown to directly inhibit the nuclear-resident 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn2. In yeast, high levels of PAP inhibit Xrn2 and lead to the accumulation of aberrant unprocessed RNA substrates, including the 5.8S rRNA subunit. Indeed, we were able to detect immature partially unprocessed 5.8S rRNA species exclusively in Bpnt1 null livers (Fig. 4C). In addition, its accumulation is repressed in double knockouts and correlates with the reduction in PAP (Fig. 5B). However, it is important to note that the relative levels of mature 5.8S rRNA seem normal in Bpnt1 null liver tissue. These data indicate that the rate of rRNA processing may be altered or that a specialized minor pool of substrates is failing to mature. Thus, although we suspect that impaired Xrn2 activity may contribute to the development of liver failure in Bpnt1 null mice, further study will be necessary to delineate its precise role.

The accumulation of immature ribosomal RNA and the defects in nucleolar architecture are intriguing in light of the importance of the nucleolus in ribosome biogenesis. Taken along with observed repression of translation and reduced levels of rough endoplasmic reticulum, our data are most consistent with a model in which PAP accumulation may alter ribosome biogenesis. Mammalian ribosomes, which contain nearly 7 kb of RNA and more than 100 core and accessory ribosomal proteins, represent an immensely complex assembly process and constitute a significant fraction of total energy expenditure, particularly in professional metabolic cells such as hepatocytes (34, 35). Notably, among the myriad steps, p53 stabilization and cell-cycle arrest have been reported as important markers of impaired ribosome biogenesis (36). Future studies will be aimed at determining precisely which steps along the complex pathway are influenced by the accumulation of PAP and loss of 3′-nucleotidase function.

Our data describe an unexpected role for the 3′-nucleotidase Bpnt1 in hepatic function. As a result of global translation repression in the liver, Bpnt1 null mice are unable to maintain sufficient serum protein levels, leading to whole-body edema and lethality. Through the use of biochemical analysis and forward genetics we were able to determine that the accumulation of Bpnt1’s substrate PAP is necessary for the development of liver failure. We also discovered a significant morphological alteration to Bpnt1 null hepatocytes that strongly correlated with the accumulation of PAP and suggested that condensed nucleoli might be useful as a histological biomarker for impaired cytoplasmic 3′-nucleotidase activity in future studies. Because of the unique presentation, our findings help to define a unique murine model of intrinsic hepatocellular disease, one that is due to a previously undescribed molecular defect and not the result of a dietary change or pharmacological insult. In addition, because the key components of the sulfate assimilation pathway are strongly conserved among mammals, we suspect that loss of function mutations in human Bpnt1 might recapitulate the hepatic defects seen in null mice and provide a genetic basis for a subset of idiopathic liver pathologies. The genetic strategy we report that reverses the physiological defects in Bpnt1 deficient mice is tantalizing and provides a precedent for designing pharmacological approaches aimed at overcoming 3′-nucleotidase deficiency.

Materials and Methods

Serum Analysis and in Vivo 3H-Leucine Protein Labeling.

After killing by CO2 exposure, whole blood was collected from the right ventricle. Serum was purified using serum separator tubes (BD), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Serum chemistries including albumin levels and liver/kidney panels were analyzed by the University of North Carolina Animal Clinical Chemistry and Gene Expression Laboratory. For in vivo serum protein labeling, two heterozygote and two homozygous null animals were each injected i.p. with 150 μCi of 3H-Leucine (Perkin-Elmer). Thirty minutes after injection animals were killed, and serum was isolated as above. Two microliters of each serum sample were run on duplicate 10% (wt/vol) SDS polyacrylamide gels. One gel was treated for fluorography using EN3HANCE (Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and exposed to BioMax MS film (Kodak) for 30 d at −80 °C. The other gel was stained with Coomassie Blue for reference, band isolation, and mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry was performed in collaboration with T. Haystead’s laboratory at Duke University.

Histology, Staining, and Electron Microscopy.

For tissue analysis, animals were killed by CO2 exposure, blood was collected by cardiac stick, and the body was perfused transcardially with 30 mL of PBS (pH 7.4). Tissues for histology were fixed in 10% (wt/vol) formalin (VWR) for 2 d then embedded in paraffin by the Duke University Medical Center Immunohistology Research Laboratory. Sections of 5 μm were stained for H&E by standard protocols. For immunohistochemistry, sections were blocked, stained, and visualized with DAB according to standard procedures. Primary antibodies recognizing fibrillarin (Abcam) and B23 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were incubated at 4 °C overnight. Tissues for Oil Red O staining were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde/1× PBS overnight, cryoprotected overnight in 30% (wt/vol) sucrose 0.1 M phosphate buffer at 4 °C, and sectioned at 10 μm using a Leica CM3050 S cryostat. Oil Red O staining was performed according to standard procedures. Slides were imaged on a Nikon TE2000 inverted fluorescent microscope. Tissues for electron microscopy were fixed, processed, and stained by the Duke Electron Microscopy Service in the Department of Pathology. Hepatic lipids were extracted by the Folch method, separated on silica gel TLC plates (GE Healthcare), and visualized by charring.

Liver PAPS and PAP Analysis.

Hepatic PAPS and PAP levels were measured using a combination of two previously published protocols (26, 27). Briefly, frozen liver slices (∼150 mg) were boiled for 3 min in 5 μL of PAP isolation buffer [50 mM glycine (pH 9.2)] per mg of tissue and disrupted using a PowerGen 700 homogenizer (Fisher Scientific, power “4”) and disposable hard tissue generators (Omni International). This process was repeated once more before transferring the samples to ice. Homogenates were clarified by centrifugation at 16,100 × g, 4 °C for 20 min. After addition of 0.2 volumes of CHCl3, mixtures were shaken vigorously and then centrifuged at 16,100 × g, 4 °C for 20 min. Finally, the upper aqueous phases were collected. The final extract was stable at −80 °C for at least 3 mo. To quantify PAP levels, we developed a simple colorimetric microplate absorbance assay in which recombinant mouse Sult1a1-GST is used to transfer a sulfate group from p-nitrophenyl sulfate to 2-naphthol, using PAPS or PAP as a catalytic cofactor. Briefly, 10 μL of the tissue lysate or PAP standard was incubated with 190 μL of PAP reaction mixture [100 mM bis·Tris propane (pH 7.0), 2.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2.5 mM p-nitrophenyl sulfate, 1 mM β-naphthol, and 1 μg of PAP-free recombinant mouse GST-Sult1a1]. Reactions velocities were determined by monitoring the production of 4-nitrophenol at 400 nm. Unknown concentrations of PAP in lysates were interpolated from Michaelis-Menten one-site binding curves of initial velocity vs. PAP concentration via Prism 5 software (GraphPad).

For HPLC analysis, extracts were isolated with 0.6 M TCA by homogenization. After TCA extraction with ethyl-ether, lysates were clarified by centrifugation. Nucleotides were then separated by HPLC (Waters) using a 5-μm partisphere SAX column (Whatman) on a 60-min linear gradient from 10 mM NH4H2PO4 (pH 3.7) to 500 mM KCl, 250 mM NH4H2PO4 (pH 4.5). Eluted nucleotides were detected by inline UV absorption at 259 nm (Waters).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Cole, B. Speer, M. Quarmyne, A. Krolik, and Drs. S. M. Wu and T. Tafari for technical assistance; members of T. Haystead’s laboratory for performing the mass spectrometry; and members of J.D.Y.’s laboratory and J. Hudson for helpful discussions, critical reading of the manuscript, and constructive comments. This work was supported by funds from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL-55672.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1205001110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kuntz E. Hepatology, Textbook and Atlas. 3rd Ed. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaller J. Human Blood Plasma Proteins: Structure and Function. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ionescu C, Caira MR. Drug Metabolism: Current Concepts. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ioannides C. Royal Society of Chemistry . Cytochromes P450: Role in the Metabolism and Toxicity of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamage N, et al. Human sulfotransferases and their role in chemical metabolism. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90(1):5–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaassen CD, Boles JW. Sulfation and sulfotransferases 5: The importance of 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) in the regulation of sulfation. FASEB J. 1997;11(6):404–418. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.6.9194521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alnouti Y, Klaassen CD. Tissue distribution and ontogeny of sulfotransferase enzymes in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2006;93(2):242–255. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson BH, York JD. Roles for nucleotide phosphatases in sulfate assimilation and skeletal disease. Adv Biol Regul. 2012;52(1):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López-Coronado JM, Bellés JM, Lesage F, Serrano R, Rodríguez PL. A novel mammalian lithium-sensitive enzyme with a dual enzymatic activity, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate phosphatase and inositol-polyphosphate 1-phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(23):16034–16039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiegelberg BD, Xiong JP, Smith JJ, Gu RF, York JD. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian lithium-sensitive bisphosphate 3′-nucleotidase inhibited by inositol 1,4-bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(19):13619–13628. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederick JP, et al. A role for a lithium-inhibited Golgi nucleotidase in skeletal development and sulfation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(33):11605–11612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801182105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.York JD, Ponder JW, Majerus PW. Definition of a metal-dependent/Li(+)-inhibited phosphomonoesterase protein family based upon a conserved three-dimensional core structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(11):5149–5153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sohaskey ML, Yu J, Diaz MA, Plaas AH, Harland RM. JAWS coordinates chondrogenesis and synovial joint positioning. Development. 2008;135(13):2215–2220. doi: 10.1242/dev.019950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vissers LELM, et al. Chondrodysplasia and abnormal joint development associated with mutations in IMPAD1, encoding the Golgi-resident nucleotide phosphatase, gPAPP. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(5):608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuwald AF, et al. cysQ, a gene needed for cysteine synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12 only during aerobic growth. J Bacteriol. 1992;174(2):415–425. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.415-425.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murguía JR, Bellés JM, Serrano R. A salt-sensitive 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase involved in sulfate activation. Science. 1995;267(5195):232–234. doi: 10.1126/science.7809627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng Z, Verma DP. A rice HAL2-like gene encodes a Ca(2+)-sensitive 3′(2′),5′-diphosphonucleoside 3′(2′)-phosphohydrolase and complements yeast met22 and Escherichia coli cysQ mutations. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(49):29105–29110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quintero FJ, Garciadeblás B, Rodríguez-Navarro A. The SAL1 gene of Arabidopsis, encoding an enzyme with 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase and inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase activities, increases salt tolerance in yeast. Plant Cell. 1996;8(3):529–537. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyamoto R, et al. Tol1, a fission yeast phosphomonoesterase, is an in vivo target of lithium, and its deletion leads to sulfite auxotrophy. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(13):3619–3625. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.13.3619-3625.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong L, et al. FIERY1 encoding an inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase is a negative regulator of abscisic acid and stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2001;15(15):1971–1984. doi: 10.1101/gad.891901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim BH, von Arnim AG. FIERY1 regulates light-mediated repression of cell elongation and flowering time via its 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase activity. Plant J. 2009;58(2):208–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson PB, et al. The nucleotidase/phosphatase SAL1 is a negative regulator of drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;58(2):299–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Biswas I. 3′-Phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphate phosphatase activity is required for superoxide stress tolerance in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(13):4330–4340. doi: 10.1128/JB.00184-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franz CP, Croze EM, Morré DJ, Schreiber G. Albumin secreted by rat liver bypasses Golgi apparatus cisternae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;678(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramachandran R, Kakar S. Histological patterns in drug-induced liver disease. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62(6):481–492. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.058248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazelton GA, Hjelle JJ, Dills RL, Klaassen CD. A radiometric method for the measurement of adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulfate in rat and mouse liver. Drug Metab Dispos. 1985;13(1):30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin ES, Yang YS. Colorimetric determination of the purity of 3′-phospho adenosine 5′-phosphosulfate and natural abundance of 3′-phospho adenosine 5′-phosphate at picomole quantities. Anal Biochem. 1998;264(1):111–117. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dichtl B, Stevens A, Tollervey D. Lithium toxicity in yeast is due to the inhibition of RNA processing enzymes. EMBO J. 1997;16(23):7184–7195. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurima K, et al. A member of a family of sulfate-activating enzymes causes murine brachymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(15):8681–8685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh B, Schwartz NB. Identification and functional characterization of the novel BM-motif in the murine phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate (PAPS) synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):71–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sugahara K, Schwartz NB. Defect in 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate formation in brachymorphic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76(12):6615–6618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rens-Domiano SS, Roth JA. Inhibition of M and P phenol sulfotransferase by analogues of 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate. J Neurochem. 1987;48(5):1411–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gamage NU, Tsvetanov S, Duggleby RG, McManus ME, Martin JL. The structure of human SULT1A1 crystallized with estradiol. An insight into active site plasticity and substrate inhibition with multi-ring substrates. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(50):41482–41486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fatica A, Tollervey D. Making ribosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Connolly K, Culver G. Deconstructing ribosome construction. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(5):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulon S, Westman BJ, Hutten S, Boisvert FM, Lamond AI. The nucleolus under stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.