Abstract

Recently, the concept of ligand-directed signaling—the ability of different ligands of an individual receptor to promote distinct patterns of cellular response—has gained much traction in the field of drug discovery, with the potential to sculpt biological response to favor therapeutically beneficial signaling pathways over those leading to harmful effects. However, there is limited understanding of the mechanistic basis underlying biased signaling. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is a major target for treatment of type-2 diabetes and is subject to ligand-directed signaling. Here, we demonstrate the importance of polar transmembrane residues conserved within family B G protein-coupled receptors, not only for protein folding and expression, but also in controlling activation transition, ligand-biased, and pathway-biased signaling. Distinct clusters of polar residues were important for receptor activation and signal preference, globally changing the profile of receptor response to distinct peptide ligands, including endogenous ligands glucagon-like peptide-1, oxyntomodulin, and the clinically used mimetic exendin-4.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest group of cell-surface proteins and mediate signal transduction across cell membranes by recognizing a wide range of extracellular stimuli (1). They signal through heterotrimeric G proteins, as well as various G protein-independent mechanisms (2). These receptors exist in a dynamic equilibrium between different conformational states and activation occurs through a number of intermediate conformations (3, 4). This equilibrium is not only controlled by the binding of specific receptor ligands and effector proteins but is also supplemented by clusters of residues within the receptor that act to stabilize subsets of receptor conformations (5).

Polar transmembrane (TM) residues are rarely found within the core of the membrane bilayer because their insertion in a hydrophobic environment is energetically unfavorable (6). Therefore, most polar residues in TM helices are buried within the interior of the protein, often lining internal water-filled cavities and forming hydrogen-bond interactions with buried water molecules and other polar residues (7, 8). Consequently, they play essential roles in the function of α-helical membrane proteins by mediating and stabilizing their helical interactions (9), in addition to playing key roles in transmission of signals across membranes through forming interactions with ligands and establishing interaction networks required for protein conformational changes (10).

A number of highly conserved polar residues are present in the family A subclass of GPCRs, and there is a wealth of information confirming their functional role. In these receptors, key conformational changes associated with activation occur through local changes in structural constraints that involve reorganization of hydrogen bonds between the polar residues and buried waters (11–14). Recent studies also revealed that distinct ligands interacting at the same receptor can stabilize different subsets of conformational states at the expense of others, which in turn can lead to the engagement of different intracellular effectors (15–17). It is these phenomena that can provide the mechanistic basis for biased agonism.

Family B GPCRs are an important class of physiological and therapeutic targets that are pleiotropically coupled, and there is evidence of ligand-directed stimulus bias for both natural and synthetic ligands of these receptors (18–20). The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) is a prototypical member of this family that is activated by a range of endogenous and exogenous peptides that are used for the treatment of type-2 diabetes, and these ligands can elicit stimulus bias (18). These attributes make the GLP-1R an ideal candidate to study the molecular basis of receptor activation that may lead to both pathway-biased and ligand-dependent signaling occurring in family B GPCRs.

Although family B GPCRs do not share the conserved polar residues that are essential for family A GPCR function, they possess their own unique set of highly conserved intramembranous polar residues that have the potential to serve an role analogous to those in family A. Using the GLP-1R as a model, we have combined mutagenesis with molecular modeling to assess the role of these conserved polar residues (Fig. S1). This study demonstrates the importance of these residues for protein folding and expression, peptide binding, and in controlling activation transition, ligand-biased and pathway-biased signaling.

Results

Universal Numbering System for Residues in Family B GPCRs.

Residues were numbered using a system similar to the nomenclature used for family A GPCRs (21). The most conserved residue in each family B GPCR TM domain (Fig. S1) was assigned the locant of .50, and this number is preceded by the TM number. Each residue is numbered according to its relative position to the residue at .50 in each helix and its absolute residue number is shown in superscript.

Conserved Polar Residues May Form Functionally Important Hydrogen Bonding Networks.

To aid in understanding of mutational data, a model was generated of the GLP-1R TM bundle (Fig. S1). Predicted interactions formed by conserved polar side chains are listed in Table S1. Inspection of the model revealed two extensive hydrogen-bond networks formed between polar residues in TMs 2, 3, 6, and 7 and buried waters (Fig. S1). Three small polar residues, S1.50155, S2.56186, and S7.47392, reside outside of these networks and are predicted to facilitate packing between individual TMs.

Experimental Analysis of GLP-1R Constructs.

WT and mutant GLP-1Rs were isogenically integrated into FlpIn-Chinese hamster ovary (FlpInCHO) cells by recombination. Antibody detection of the N-terminal c-myc epitope and whole-cell binding using [125I]exendin (9–39) were used to study cell-surface expression (Fig. S2 and Table 1). Ligand affinities were calculated by whole-cell competition equilibrium binding studies using [125I]exendin (9–39) with the agonists GLP-1(7–36)NH2 (GLP-1), oxyntomodulin, and exendin-4 and an antagonist exendin (9–39) (Fig. S2 and Table 1). To assess the role of chosen residues in strength of coupling to signaling pathways, all were assessed in three pathways, each of which has been physiologically linked to GLP-1R–mediated insulin release [cAMP, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), and intracellular calcium (iCa2+) mobilization]. Agonist concentration response curves were generated using the three peptide agonists (Figs. S3–S5) and pEC50 and the maximum response (Emax) values determined. Most mutants dramatically altered potencies and/or Emax in signaling through at least one pathway, and all mutations that altered cell-surface expression and/or binding affinity resulted in altered EC50 and/or Emax values. To delineate effects on affinity and efficacy, concentration response curves were analyzed by an operational model of agonism to determine relative signaling efficacy estimates (logτ values). To account for the potential confounding effect of different expression levels, these τ values were normalized to what they would be if the mutant receptor were expressed at the same level as WT (logτc values, Table S2). Therefore, where possible, all comparisons between WT and mutant receptors were performed on logτc values.

Table 1.

Ligand affinities and cell-surface expression of GLP-1R polar TM mutations

| Ligand binding affinity, pKi |

Cell-surface expression, % wt |

|||||

| Receptor | GLP-1(7–36)NH2 | Oxyntomodulin | Exendin-4 | Exendin (9–39) | ELISA | Bmax |

| WT | 8.67 ± 0.05 | 7.26 ± 0.04 | 8.97 ± 0.04 | 8.11 ± 0.04 | 100 ± 1 | 100 ± 2 |

| S1.50155A | 8.29 ± 0.10* | 7.28 ± 0.13 | 8.43 ± 0.14* | 8.08 ± 0.07 | 55 ± 2* | 48 ± 3* |

| H2.50180A | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18 ± 1* | ND* |

| S2.56186A | 8.60 ± 0.06 | 7.26 ± 0.05 | 9.02 ± 0.05 | 7.94 ± 0.07 | 100 ± 2 | 114 ± 4 |

| R2.60190A | 7.37 ± 0.09* | 7.60 ± 0.13 | 7.30 ± 0.08* | 7.58 ± 0.08* | 53 ± 3* | 44 ± 2* |

| N3.43240A | 8.19 ± 0.07* | 7.43 ± 0.05 | 8.64 ± 0.06 | 8.29 ± 0.08 | 87 ± 3 | 92 ± 2 |

| E3.50247A | ND | ND | ND | ND | 18 ± 4* | ND* |

| N5.50320A | 7.42 ± 0.11* | 6.36 ± 0.05* | 7.44 ± 0.07* | 8.38 ± 0.07 | 95 ± 4 | 114 ± 8 |

| T6.42353A | ND | ND | ND | ND | 30 ± 2* | ND* |

| H6.52363A | 7.31 ± 0.08* | 6.46 ± 0.11* | 7.54 ± 0.11* | 7.41 ± 0.09* | 59 ± 4* | 53 ± 2* |

| S7.47392A | 8.42 ± 0.06 | 7.09 ± 0.07 | 8.72 ± 0.07 | 8.45 ± 0.06* | 98 ± 3 | 92 ± 1 |

| Q7.49394A | 8.56 ± 0.08 | 7.26 ± 0.06 | 8.87 ± 0.07 | 8.18 ± 0.06 | 103 ± 3 | 111 ± 2 |

| Y7.57402A | ND | ND | ND | ND | 21 ± 6* | ND* |

| N7.61406A | 8.61 ± 0.06 | 7.29 ± 0.04 | 8.77 ± 0.21 | 8.08 ± 0.05 | 90 ± 3 | 119 ± 2 |

Ligand affinity (Ki) and Bmax estimates were derived from competition binding studies. Cell-surface expression was determined by antibody detection of the N-terminal c-Myc epitope tag. All values are expressed as means ± SEM of four to six independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. Data were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett’s posttest (*P < 0.05). ND, data not experimentally defined because no specific radioligand binding could be detected above background in either whole cells or crude membrane preparations.

Characterization of the Central Interaction Network.

R2.60190, N3.43240A, N5.50320, H6.52363, Q7.49394, and Y7.57402 were predicted to reside in a central interaction network (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). R2.60190A, H6.52363A, and Y7.57402A significantly impaired cell-surface expression compared with WT; however, expression of N3.43240A, N5.50320A, and Q7.49394A were similar to WT (Fig. S2 and Table 1).

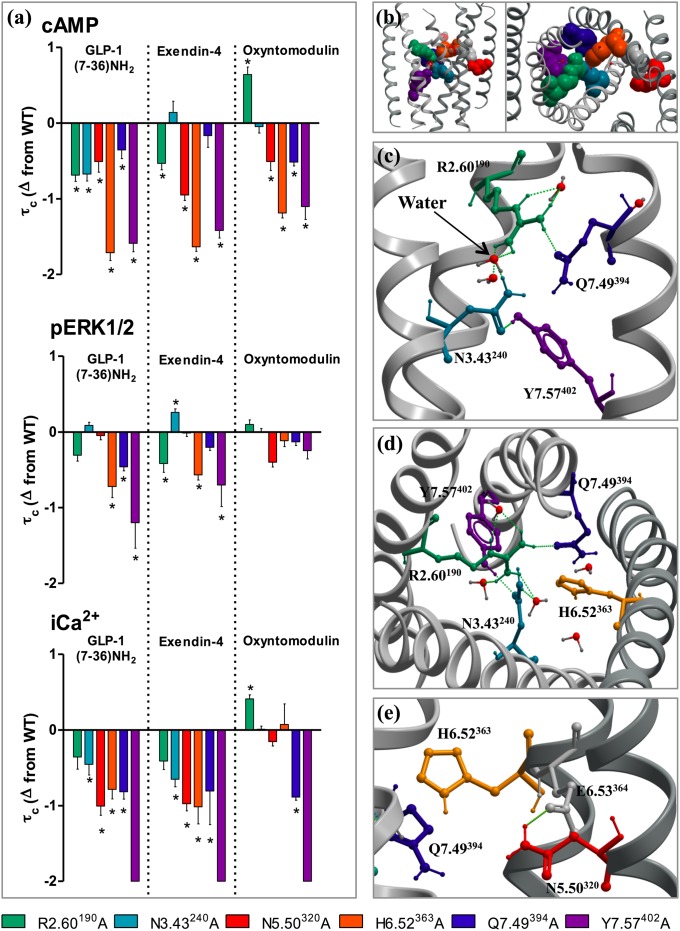

Fig. 1.

Ligand-dependent and pathway-dependent effects upon mutation of residues composing the predicted central interaction network. (A) Differences in the coupling efficiency (logτc) of GLP-1, exendin-4, and oxyntomodulin to three signaling pathways [cAMP (Top), pERK1/2 (Middle), and iCa2+ mobilization (Bottom)] at individual mutants compared with the WT receptor. Statistical significance of changes in coupling efficacy in comparison with WT was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's posttest, and values are indicated with an asterisk (*P < 0.05). All values are logτc ± SEM of four to six independent experiments, conducted in duplicate. (B) The model of the TM domain of the GLP-1R from the side (Left) and top (Right) highlighting the location of each of the six residues mutated. (C) Interactions in the model between R2.60190, N3.43240, Q7.49394, and Y7.57402. (D) View of the TM domain from the top showing the location of H6.523563 in relation to R2.60190, N3.43240, Q7.49394, and Y7.57402. (E) N5.50320 forms an interaction with E6.53364, located next to H6.523563 in the GLP-1R model.

R2.60190A displayed reduced affinity for GLP-1 and exendin-4, but not oxyntomodulin. The antagonist affinity was also significantly decreased; however, the loss in agonist affinity was much greater (20- to 47-fold compared with 3-fold) (Fig. S2 and Table 1). Both N3.43240A and Q7.49394A had similar affinity to WT for all ligands with the exception of GLP-1 at N3.43240A, which was significantly reduced (Table 1). H6.52353A and N5.50320A reduced the affinity for all three agonists and H6.52353A also reduced the affinity of antagonist, exendin (9–39), but to a lesser extent [23- to 26-fold (agonists) and 5-fold (antagonist)]. Interestingly, for N5.50320A, greater reductions were observed for the higher-affinity agonists GLP-1 and exendin-4 (38- to 59-fold) than for oxyntomodulin (9-fold). Due to very low expression of Y7.57402A, no radioligand binding could be detected (Fig. S2 and Table 1).

Mutation to any of these six centrally located residues resulted in impaired signaling, but the effect varied depending on the particular mutation, the activating ligand, and the assay being assessed (Fig. 1). When activated by GLP-1 all six mutations significantly reduced coupling to cAMP, but effects were greater for H6.52353A and Y7.57402A. A similar trend was observed for iCa2+ mobilization; however, R2.60190A did not reach statistical significance and the impact of H6.52363A was smaller. H6.52363A, Q7.49394A, and Y7.57402A also displayed impaired pERK1/2 responses. In contrast, no statistically significant effects on GLP-1-mediated pERK1/2 signaling were observed at R2.60190A, N2.43240A, or N5.50320A compared with WT (Fig. 1 and Table S2).

Exendin-4–mediated responses were reduced to an extent similar to GLP-1 in all three pathways for R2.60190A, N5.50320A, H6.52363A, and Y7.57402A. However, exendin-4 displayed a different signaling profile at N3.43240A and Q7.49394A (Fig. 1 and Table S2). N3.43240A did not affect cAMP signaling and showed a small significant increase in pERK1/2 coupling. Neither cAMP nor pERK1/2 reponses were significantly altered at Q7.49394A. However, in iCa2+ mobilization both mutations had reductions in efficacy equivalent to those mediated by GLP-1.

The signaling profiles of these six mutations were distinct when activated by oxyntomodulin (Fig. 1). Coupling to cAMP was impaired at N5.50320A, H6.52363A, Q7.49394A, and Y7.57402A and, like the other ligands, these effects were greater at H6.52363A and Y7.57402A. However, of these, only Q7.49394A and Y7.57402A showed heavily impaired iCa2+ mobilization. Additionally, N3.43240A had no effect on functional responses mediated by oxyntomodulin, and R2.60190A significantly enhanced coupling to cAMP and iCa2+. Interestingly, none of these mutations altered oxyntomodulin signaling to pERK1/2 (Fig. 1).

Because the model suggested that both N3.43240 and Q7.49394 interact with R2.60190, a double mutation (N3.43240A/Q7.49394A) was generated. This receptor displayed impaired coupling to all three pathways when activated by GLP-1. Unlike the single mutations, which had little impact on exendin-4–mediated cAMP and pERK1/2, this elicited impaired responses for both pathways, indicating that both these interactions are important for exendin-4–mediated signal transmission (Fig. S3). However, oxyntomodulin favors a different mechanism of activation because the double mutation had little effect in pERK1/2 signaling and no greater effect than Q7.49394A alone on coupling to cAMP and iCa2+.

Calculation of bias factors between signaling pathways showed that relative to WT, R2.60190A was significantly biased toward iCa2+ mobilization when activated by exendin-4, R2.60190 and N3.43240 are biased toward pERK1/2 when activated by GLP-1 (and N3.43240 for oxyntomodulin), and significant bias was observed for Q7.49394A toward cAMP and pERK1/2 relative to iCa2+ for all ligands (Fig. S6 and Table S3). At H6.52353A, GLP-1 was significantly biased toward iCa2+ mobilization and to some extent pERK1/2 over cAMP, whereas oxyntomodulin and exendin-4 were biased toward pERK1/2. All three ligands were heavily biased toward pERK1/2 at N5.50320A, but little bias was observed at Y7.57A402 (Fig. S6 and Table S3). Collectively, these data suggest that residues forming this central interaction network are crucial for fine-tuning ligand and pathway-specific receptor responses.

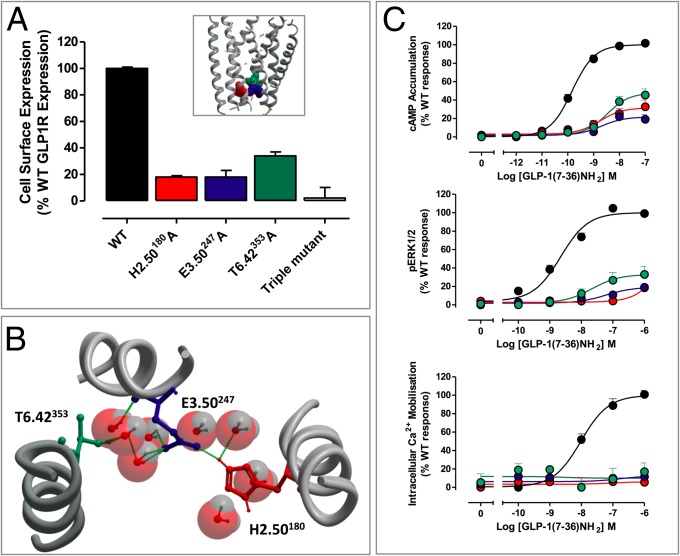

Characterization of Mutants in a Hydrogen Bonding Network Near the Cytoplasmic Face.

The predicted cytoplasmic-face hydrogen-bond network involved the amino acid side chains of H2.50180 (TM2), E3.50247 (TM3), and T6.42353 (TM6). Ala substitution resulted in receptors that were very poorly expressed (18 ± 1%, 18 ± 4%, and 30 ± 2% of WT for H2.50180A, E3.50247A, and T6.42353A, respectively) (Fig. 2, Fig. S2, and Table 1). [125I]exendin (9–39) binding at these mutants was not detectable, so agonist affinity could not be calculated. Weak or no signaling was detectable for these receptors in any measured pathway with any of the three agonists. Mutation of all three residues together resulted in a complete loss of receptor expression and no detectable function (Fig. 2 and Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Effects on mutation of residues located in the hydrogen-bonding network located at the cytoplasmic face. (A) Cell-surface expression relative to the WT receptor (by antibody detection of the N-terminal cMyc epitope tag) of H2.50180A, E3.50247A, T6.42353A, and the triple mutant (H2.50180A/E3.50247A/T6.42353A). (B) Interactions formed between H2.50180A, E3.50247A, T6.42353A, and waters in the GLP-1R model. (C) Dose–response curves generated in response to GLP-1 in cAMP accumulation (Top), pERK1/2 (Middle), and iCa2+ mobilization (Bottom) assays.

Because H2.50180 was protonated in the GLP-1R model, this side chain is predicted to form a hydrogen bond with N7.61406 in TM7 (Fig. S7). N7.61 is absolutely conserved in family B GPCRs; however, no dramatic alterations in signaling were observed for N7.61406A, although subtle changes to receptor bias occurred for all ligands, with a selective increase in iCa2+ signaling, no change in cAMP, and a small reduction in pERK1/2, albeit none of these changes reached statistical significance (Figs. S4 and S6 and Tables S2 and S3).

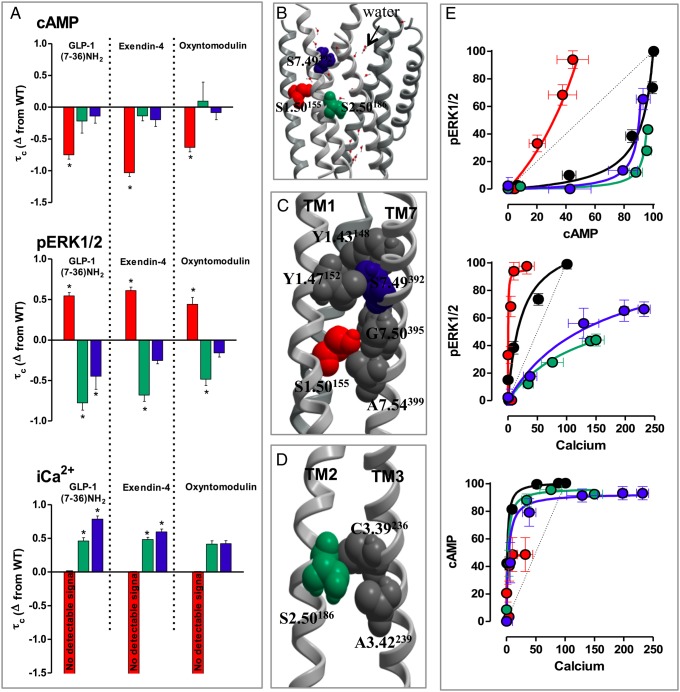

Conserved Small Polar Residues Fine-Tune Activation Transition, Resulting in Controlled Activation of Different Intracellular Signaling Pathways.

The three remaining conserved polar TM residues are all serines in the GLP-1R, two of which are small residues in all family B GPCRs (1.50 and 2.56) (Fig. S2). Mutation of S2.56186 and S7.47392 had no effect on the cell-surface expression but S1.50155A expression was significantly impaired (Fig. S2). S2.56186A and S7.47392A did not alter the affinity for any agonist, whereas S1.50155A displayed small reductions in affinity for GLP-1 and exendin-4 but not oxyntomodulin (Fig. S2 and Table 1).

Interestingly, all three mutants had global effects on stimulus bias regardless of the activating ligand. S1.50155A had reduced coupling efficiency for cAMP and iCa2+ mobilization (where no response was detectable) yet enhanced efficacy for pERK1/2. In contrast, S2.56186A and S7.47392A showed efficacy similar to WT for cAMP, reduced efficacy for pERK1/2, and an enhanced ability to mobilize iCa2+ (Fig. 3, Fig. S5, and Table S2). The changes in global bias induced by these mutations can be clearly seen in bias plots (Fig. 3) that provide a visual representation of relative pathway response. Calculation of bias factors confirmed S1.50155A was prejudiced toward pERK1/2 relative to cAMP and iCa2+, whereas S2.46186A and S7.47392A exhibited bias toward iCa2+ signaling relative to cAMP and pERK1/2, although these bias factors did not reach statistical significance for all ligands (Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Stimulus bias effects upon mutation of small polar residues in TMs 1, 2, and 7. (A) The coupling efficiency relative to WT (Δlogτc) of GLP-1, exendin-4, and oxyntomodulin to three signaling pathways [cAMP (Top), pERK1/2 (Middle), and iCa2+ mobilization (Bottom)] at S1.50155A, S2.56186A, and S7.47392A. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance and Dunnett's posttest (*P < 0.05). (B) The relative location of S1.50155, S2.56186, and S7.47392 in the GLP-1R model. (C) Predicted packing interactions between TMs 1 and 7 formed by S1.50155 and S7.47392. (D) Predicted packing interactions formed by S2.50186 between TMs 2 and 3. (E) Bias plots of WT, S1.50155A, S2.50186A, and S7.47392A for cAMP vs. pERK1/2 (Top), pERK1/2 vs. iCa2+ mobilization (Middle) and cAMP vs. iCa2+ mobilization (Bottom) for GLP-1. Data for each pathway are normalized to the maximal response elicited by peptide at the WT GLP-1R and analyzed with a three-parameter logistic equation as defined in Eq. S1, with 150 points defining the curve. A similar bias was observed when cells expressing receptors were stimulated with exendin-4 and oxyntomodulin as evidenced by bias factor calculations (Fig. S6 and Table S3).

Discussion

Polar residues in membrane proteins are under evolutionary pressure for conservation and hence maintain common functions with essential roles in stability, activation, and interhelical association through the formation of hydrogen bonds (8). Based on our GLP-1R model, two main hydrogen-bond networks involving conserved polar side chains located between TMs 2, 3, 6, and 7 and waters are evident. Six conserved residues lie within a centrally located network including R2.60190, N3.43240, N5.50320, H6.52363, Q7.49394, and Y7.57402. Mutations in this central core often [although not in all cases (e.g., N3.43240A)] had similar effects on cAMP and iCa2+ mobilization, but effects on pERK1/2 signaling were less pronounced. This suggests that fine control of GLP-1R signaling is linked to changes in interactions formed by these buried polar residues. In addition, although in the majority of cases activation by GLP-1 and exendin-4 was similar for the six different mutations across three signaling pathways, oxyntomodulin had a strikingly different pattern of behavior, and only the mutation of Y7.57402 (and to some extent Q7.49394) had a trend consistent with that of the other two peptides. Therefore, oxyntomodulin’s interaction with the GLP-1R and/or the precise mechanism by which it activates the receptor is different from that of the other peptides. This is in agreement with previous studies on bias at the WT receptor (18). In addition, Ala mutations to residues in extracellular loop 2 differentially altered ligand interactions and functional responses for oxyntomodulin compared with GLP-1 and exendin-4 (22).

R2.60190A significantly lowered the affinity and efficacy of GLP-1 and exendin-4. In other receptors belonging to the family B subclass [vasoactive intestinal polypeptide type-1 and type-2 receptors (VPAC1R and VPAC2R) and secretin receptor (SecR)] the equivalent residue has been argued to interact with an Asp at position 3 of the agonist ligand (23, 24). GLP-1 and exendin-4 both contain an equivalent Glu at position 3 and therefore R2.60190 could serve a similar role. Interestingly oxyntomodulin contains a Gln at position 3 and the affinity of this peptide was unaltered at R2.60190A, supporting a differential mode of binding. However, the antagonist exendin (9–39) does not contain the first eight amino acids, and yet its binding was also reduced, albeit to a lesser extent.

Although less common, there were also significant differences in effect of mutation between pathways activated by GLP-1 and exendin-4 (Fig. 1 and Fig. S6). This indicates there are differing mechanisms of receptor activation for these two ligands. Thus, all three of the related peptides activate the receptor via subtly different mechanisms, which is particularly relevant becaus GLP-1 and oxyntomodulin both act endogenously and exendin-4 is used clinically to mimic the physiological functions of GLP-1.

All GPCRs are able to activate common G proteins, suggesting a conserved mechanism for G protein activation. For transition from inactive to active conformations, family A GPCRs undergo a global rearrangement of the helix bundle that shifts the cytoplasmic end of TM6 (and to a smaller extent TM5) away from the receptor core by a rotation in TM6, aided by a bend in the helix caused by a highly conserved proline (P6.50) (25–27). Early studies performed using Zn2+ binding suggest similar helical movements of TM6 occur in the β2AR (a well characterized family A GPCR) and the parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor (a family B GPCR) and, like family A GPCRs, family B receptors contain a highly conserved proline in TM6 that is important for coupling to G proteins (28–30). These large global changes are nonetheless mediated by small conformational changes within or near the receptor binding pocket that are propagated through the receptor core (26, 31). From this study, we propose that binding of different peptides to the GLP-1R results in differential (perhaps even minor) changes around the binding pocket that are linked either directly through binding or indirectly via other interactions to a hydrogen-bond network involving the conserved residues R2.60190, N3.43240, Q7.49394, structural waters and other nonconserved residues. This is likely to be an early event in receptor activation because the different ligands had different effects between mutations and across signaling pathways and no mutant displayed the same profile in all pathways for the same ligand or for all ligands in the same pathway. A role for these three conserved residues (2.60, 3.43, and 7.49) was also proposed for the early stages of activation of the VPAC1R (32).

Although the magnitude of effect upon mutation varied, the effects on function observed upon mutation of N5.50320, H6.52363, and Y7.57402 were more consistent between pathways and ligands and thus may assist the formation of larger-scale conformational changes within TMs 5 and 6, transmitting conformational movements from the early stages of activation that lead to coupling of effectors at the cytoplasmic face. Potentially, these residues may play roles in activation analogous to W6.48 (H6.52363), Y5.58 (N5.50320), and Y7.53 (Y7.57402) in family A GPCRs (25).

H6.52363A resulted in a marked reduction in affinity of all ligands and all functional responses, independent of the decreased affinity (with the exception of oxyntomodulin-induced pERK1/2 and iCa2+). In water pockets, histidines can be readily protonated and deprotonated depending on the local environment (33). In the model, H6.52363 is only singly protonated, so it is uncharged, but changes in the protonation state owing to the exchange of bulk waters could arise owing to an opening up of the bundle upon peptide binding. If this does occur, TM6 would rotate away from TM2 and TM3 because of the proximity of the positively charged R2.60190, consistent with helical movements that occur in family A GPCRs (26, 34).

N5.50320A reduced affinity of GLP-1 and exendin-4 and their ability to activate both cAMP and iCa2+ mobilization; however, there was no change in coupling to pERK1/2. There was a similar effect on oxyntomodulin affinity and coupling to cAMP; however, in this case pERK1/2 and iCa2+ mobilization were unaltered. Our model suggests an interaction of N5.50320 with E6.53364, located next to H6.52363, that is also crucial in activation of the GLP-1R leading to cAMP signaling. Mechanistically this is interesting, because a rotation in TM6 upon activation would result in a movement of TM5 that would be aided by the proposed interaction between N5.50320 with E6.53364, opening up the helical bundle at the cytoplasmic face (Fig. S7). Mutation of N5.50320 seems to alter the ensemble of conformations that the GLP-1R can sample (or the frequency with which they sample subsets of populations) in response to agonists such that there is a greater propensity to form conformations linked to pERK1/2 than to cAMP and iCa2+. Therefore, N5.50320 may mediate receptor transitions thorough aiding movement of TM5 to open up the bundle allowing G-protein coupling but is less important for transitions enabling G-protein-independent signaling (pERK1/2).

Y7.57402A had a global impact on receptor function regardless of the activating ligand. Y7.57402 forms part of a conserved VXXXY motif that may be the family B equivalent of the NPXXY motif, playing a role similar to Y7.53 in family A GPCRs (27). Y7.57402 in the GLP-1R forms hydrophobic packing contacts through its bulky aromatic ring and a hydrogen bond interaction with N3.43240A and also waters through its polar moiety. These interactions are likely to be broken upon receptor activation and may aid transmission of signal from the hydrogen-bond network in the core of the protein to the cytoplasmic face, stabilizing conformations that allow effectors to bind.

In addition to a role in aiding conformational rearrangements R2.60190, H6.52363, and Y7.57402 are also required for efficient cell-surface expression. The reduction in cell-surface-expressed receptors for R2.60190A, H6.52363A, and Y7.57402A indicates that these mutations either disrupt trafficking/insertion of the receptor into the bilayer and/or disrupt the stability of the helical bundle. R2.60190 could perform both of these roles. In our model, His6.52363 resides in close proximity to R2.60190 and forms π stacking interactions with F6.56367 and F7.45390, polar interactions with T7.46391 in TM7, and hydrophobic packing with L6.49360 and L6.48359, whereas Y7.57402 packs between two phenylalanine residues in TM2. These packing interactions are likely to provide structural integrity (Fig. S7). Although we have proposed that effects on signaling following mutation of these residues may be due to their involvement in a central interaction network, these effects could also arise due to indirect effects on folding and structural integrity via other mechanisms.

The predicted bottom hydrogen-bond network involves H2.50180A, E3.50247, T6.42353, and multiple waters. Mutation of these residues individually resulted in heavily impaired cell-surface expression and subsequently impaired functional responses to all ligands in all pathways. One proposal is that H2.50180 and E3.50247 play a role in family B GPCRs similar to the highly conserved D(E)RY motif in family A GPCRs. Family A GPCRs also have a proposed lock between TMs 3 and 6 that stabilize these receptors in their inactive conformation (35, 36). The extended network in our model revealed water-connected hydrogen-bond interactions between E3.50247 and T6.42353 that may play a similar role, locking the receptor in an inactive conformation. Often in family A GPCRs, mutation of either the D(E)RY motif or the interacting residues in TM6 (E6.30 and T6.34) results in constitutive activity (36). However, sometimes this manifests as a reduction in cell-surface expression, due to a destabilization of the receptor structure and/or constitutive internalization (36). The inability to detect binding in crude membrane fractions and whole cells upon mutation of these residues supports a crucial role of this bottom network for receptor folding and stability. It is also interesting to note that mutation of both H2.50 and T6.42 in the PTH and SecR receptors and of H2.50 in the VPAC1R leads to constitutive activation, supporting the evolutionarily conserved role of these residues in ground-state stabilization (37–40).

In addition to large polar and charged amino acids, mutation to three small polar residues promotes receptor conformations that altered the equilibrium between the different signaling cascades; however, these mutants had global impacts on signaling regardless of the activating ligand. Relative to WT, S1.50155A displayed significant bias toward pERK1/2 over calcium and cAMP, whereas S2.50186A and S7.47392A were biased toward iCa2+ (Fig. 3). Small weakly polar residues (Ser, Thr, and Cys) within the TM domains of membrane proteins are key determinants in helix–helix interactions (41). In our model, S1.50155 packs up against two small residues in TM7 (G7.50395 and A7.54399), aiding close packing of TMs1 and 7, and S2.50186 in TM2 packs with C3.39236 in TM3, allowing tight packing of these helices. S2.50186 is also in close proximity to A3.42239, and an interaction with this residue may occur on conformational transition (Fig. 3). It is not clear whether Ala mutation results in more tightly packed helices or creates space in the structure, but clearly subtle changes in these regions have very selective effects on the conformational landscape that the receptor can explore. Interestingly, S7.47392 in TM7 does not cause tight packing but instead borders a solvated pocket, forming a direct interaction with Y1.48148 in TM1 and through water contact with D2.68198 (Table S1). This Asp has been highlighted as a potential contact for peptides and when mutated significantly alters GLP-1R function (42). Ala mutation of S7.47392 did not alter affinity of any ligand, but its ability to selectively enhance signaling to iCa2+ but not pERK1/2 or cAMP indicated that disruption of these interactions significantly lowers the energy barrier, allowing the receptor to mobilize iCa2+. In addition, N7.61406A also resulted in an increase in iCa2+ for all ligands, although the pathway selectivity was not as pronounced as those mentioned above. Nonetheless, these effects were similar to those of S2.56186 and S7.47392 (also located in TMs 2 and 7). Taken together, these residues seem to optimally pack TM helices to allow fine-tuning of receptor response to different intracellular effectors.

Collectively, this study indicates that conserved polar residues within the TM domain of the GLP-1R are essential for structural integrity and activation transition, including signaling preferences and ligand-directed stimulus bias. This likely involves reordering of interaction networks between polar side chains and buried waters, providing a mechanism through which receptors and ligands achieve conformational complexes associated with signaling bias. The high degree of conservation of these residues suggests that they may play a similar role in signaling of other family B GPCRs.

Materials and Methods

Receptor Mutagenesis and Cell Culture.

Thirteen conserved polar residues located in the TM domain that are predicted to be buried within the core of the GLP-1R were selected for mutagenesis (Fig. S1). This was achieved using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene), and stable cell lines were generated using gateway technology (Invitrogen).

Expression, Binding, and Functional Assays.

Cell-surface expression, radioligand binding (22), cAMP accumulation, pERK1/2, and iCa2+ mobilization assays (18) were performed as previously described.

Molecular Modeling.

All atom canonical alpha helices for each TM region of the GLP-1R were generated using TINKER (43, 44). Each helix was fitted to the equivalent helix in bovine rhodopsin (1GZM) using lipid facing residue information extracted from the Trans-Membrane helix-LIPid web server. For those helices containing proline residues helices were picked from the pool of helical turns to minimize polar residue exposure to the lipid environment. A coarse-grain representation of the helical bundle was generated according to the MARTINI force field before insertion into a palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayer (45). The system was simulated for 1 µs with snapshots taken every 10 ns, then transformed from coarse-grain to all-atom representation using PULCHRA and OPUS_ROTA and scored using OPUS_PSP. The best scoring bundle was subjected to 5e8 steps in a replica exchange Monte Carlo simulation as implemented in hippo using default values. Water positions were predicted using DOWSER.

Data Analysis.

All data were analyzed using Prism 5.04 (GraphPad Software Inc.) as previously described (46).

For more details on experimental methods and data analysis, see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant 1002180, NHMRC Program Grant 519461, Australian Research Council Discovery Project DP0985210, and a Victorian Life Sciences Computation Initiative (VLSCI) Grant (VR0024) on its Peak Computing Facility at the University of Melbourne, an initiative of the Victorian Government, Australia.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1221585110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(9):639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptor signaling through beta-arrestin. Sci STKE. 2005;2005(308):cm10. doi: 10.1126/stke.2005/308/cm10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann KP, et al. A G protein-coupled receptor at work: The rhodopsin model. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34(11):540–552. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swaminath G, et al. Sequential binding of agonists to the beta2 adrenoceptor. Kinetic evidence for intermediate conformational states. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(1):686–691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unal H, Karnik SS. Domain coupling in GPCRs: The engine for induced conformational changes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33(2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isom DG, Cannon BR, Castañeda CA, Robinson A, García-Moreno B. High tolerance for ionizable residues in the hydrophobic interior of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(46):17784–17788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805113105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Illergård K, Kauko A, Elofsson A. Why are polar residues within the membrane core evolutionary conserved? Proteins. 2011;79(1):79–91. doi: 10.1002/prot.22859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou FX, Cocco MJ, Russ WP, Brunger AT, Engelman DM. Interhelical hydrogen bonding drives strong interactions in membrane proteins. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(2):154–160. doi: 10.1038/72430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran AR, Engelman DM. Sequence motifs, polar interactions and conformational changes in helical membrane proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13(4):412–417. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angel TE, Chance MR, Palczewski K. Conserved waters mediate structural and functional activation of family A (rhodopsin-like) G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(21):8555–8560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903545106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angel TE, Gupta S, Jastrzebska B, Palczewski K, Chance MR. Structural waters define a functional channel mediating activation of the GPCR, rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(34):14367–14372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deupi X, et al. Stabilized G protein binding site in the structure of constitutively active metarhodopsin-II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(1):119–124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114089108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel AB, et al. Changes in interhelical hydrogen bonding upon rhodopsin activation. J Mol Biol. 2005;347(4):803–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mary S, et al. Ligands and signaling proteins govern the conformational landscape explored by a G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(21):8304–8309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119881109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahmeh R, et al. Structural insights into biased G protein-coupled receptor signaling revealed by fluorescence spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(17):6733–6738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K. Biased signaling pathways in β2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR. Science. 2012;335(6072):1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koole C, et al. Allosteric ligands of the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) differentially modulate endogenous and exogenous peptide responses in a pathway-selective manner: implications for drug screening. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78(3):456–465. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spengler D, et al. Differential signal transduction by five splice variants of the PACAP receptor. Nature. 1993;365(6442):170–175. doi: 10.1038/365170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gesty-Palmer D, et al. 2009. A beta-arrestin-biased agonist of the parathyroid hormone receptor (PTH1R) promotes bone formation independent of G protein activation. Sci Transl Med 1(1):1ra1.

- 21.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci Receptor Mol Biol. 1995;25:366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koole C, et al. Second extracellular loop of human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) differentially regulates orthosteric but not allosteric agonist binding and function. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):3659–3673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.309369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langer I, Robberecht P. Molecular mechanisms involved in vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor activation and regulation: Current knowledge, similarities to and differences from the A family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 4):724–728. doi: 10.1042/BST0350724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Paolo EDNP, et al. Contribution of the second transmembrane helix of the secretin receptor to the positioning of secretin. FEBS Lett. 1998;424(3):207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459(7245):356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasmussen SG, et al. Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011;477(7366):549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Standfuss J, et al. The structural basis of agonist-induced activation in constitutively active rhodopsin. Nature. 2011;471(7340):656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature09795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheikh SP, et al. Similar structures and shared switch mechanisms of the beta2-adrenoceptor and the parathyroid hormone receptor. Zn(II) bridges between helices III and VI block activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(24):17033–17041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conner AC, et al. A key role for transmembrane prolines in calcitonin receptor-like receptor agonist binding and signalling: Implications for family B G-protein-coupled receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(1):20–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey RJ, Hay DL. Agonist-dependent consequences of proline to alanine substitution in the transmembrane helices of the calcitonin receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151(5):678–687. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warne T, Edwards PC, Leslie AG, Tate CG. Crystal structures of a stabilized β1-adrenoceptor bound to the biased agonists bucindolol and carvedilol. Structure. 2012;20(5):841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chugunov AO, et al. Evidence that interaction between conserved residues in transmembrane helices 2, 3, and 7 are crucial for human VPAC1 receptor activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78(3):394–401. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.063578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S, Hong M. Protonation, tautomerization, and rotameric structure of histidine: a comprehensive study by magic-angle-spinning solid-state NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(5):1534–1544. doi: 10.1021/ja108943n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheerer P, et al. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature. 2008;455(7212):497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature07330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palczewski K, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: A G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289(5480):739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rovati GE, Capra V, Neubig RR. The highly conserved DRY motif of class A G protein-coupled receptors: Beyond the ground state. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(4):959–964. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schipani E, Kruse K, Jüppner H. A constitutively active mutant PTH-PTHrP receptor in Jansen-type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. Science. 1995;268(5207):98–100. doi: 10.1126/science.7701349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schipani E, et al. Constitutively activated receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide in Jansen’s metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(10):708–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609053351004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaudin P, Maoret JJ, Couvineau A, Rouyer-Fessard C, Laburthe M. Constitutive activation of the human vasoactive intestinal peptide 1 receptor, a member of the new class II family of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(9):4990–4996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ganguli SC, et al. Protean effects of a natural peptide agonist of the G protein-coupled secretin receptor demonstrated by receptor mutagenesis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286(2):593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu W, Eilers M, Patel AB, Smith SO. Helix packing moments reveal diversity and conservation in membrane protein structure. J Mol Biol. 2004;337(3):713–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.López de Maturana RDD, Donnelly D. The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor binding site for the N-terminus of GLP-1 requires polarity at Asp198 rather than negative charge. FEBS Lett. 2002;530(1–3):244–248. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03492-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulmschneider MB, Ulmschneider JP. Membrane adsorption, folding, insertion and translocation of synthetic trans-membrane peptides. Mol Membr Biol. 2008;25(3):245–257. doi: 10.1080/09687680802020313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ulmschneider JP, Jorgensen WL. Polypeptide folding using Monte Carlo sampling, concerted rotation, and continuum solvation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(6):1849–1857. doi: 10.1021/ja0378862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH. The MARTINI force field: Coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(27):7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koole C, et al. Second extracellular loop of human glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) has a critical role in GLP-1 peptide binding and receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):3642–3658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.309328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.