Abstract

Aim

To characterize quantitatively the relationship between ABT-102, a potent and selective TRPV1 antagonist, exposure and its effects on body temperature in humans using a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling approach.

Methods

Serial pharmacokinetic and body temperature (oral or core) measurements from three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies [single dose (2, 6, 18, 30 and 40 mg, solution formulation), multiple dose (2, 4 and 8 mg twice daily for 7 days, solution formulation) and multiple-dose (1, 2 and 4 mg twice daily for 7 days, solid dispersion formulation)] were analyzed. nonmem was used for model development and the model building steps were guided by pre-specified diagnostic and statistical criteria. The final model was qualified using non-parametric bootstrap and visual predictive check.

Results

The developed body temperature model included additive components of baseline, circadian rhythm (cosine function of time) and ABT-102 effect (Emax function of plasma concentration) with tolerance development (decrease in ABT-102 Emax over time). Type of body temperature measurement (oral vs. core) was included as a fixed effect on baseline, amplitude of circadian rhythm and residual error. The model estimates (95% bootstrap confidence interval) were: baseline oral body temperature, 36.3 (36.3, 36.4)°C; baseline core body temperature, 37.0 (37.0, 37.1)°C; oral circadian amplitude, 0.25 (0.22, 0.28)°C; core circadian amplitude, 0.31 (0.28, 0.34)°C; circadian phase shift, 7.6 (7.3, 7.9) h; ABT-102 Emax, 2.2 (1.9, 2.7)°C; ABT-102 EC50, 20 (15, 28) ng ml−1; tolerance T50, 28 (20, 43) h.

Conclusions

At exposures predicted to exert analgesic activity in humans, the effect of ABT-102 on body temperature is estimated to be 0.6 to 0.8°C. This effect attenuates within 2 to 3 days of dosing.

Keywords: ABT-102, body temperature, nonmem, population modeling, tolerance, TRPV1

What is Already Known about This Subject

ABT-102 is a selective TRPV1 antagonist with robust analgesic activity in preclinical models of pain.

Accumulating evidence indicates that the TRPV1 channel is involved in body temperature regulation.

TRPV1 antagonists elevate body temperature in primates and non-primates.

What this Study Adds

We present in this report a thorough population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of the effects of ABT-102 on body temperature in humans; comprising a relatively large dataset from three phase 1 trials where body temperature was extensively monitored during ABT-102 treatment and washout.

Introduction

The transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) has been the focus of extensive research targeting new treatments for management of pain [1] and more recently other diseases [1, 2]. The TRPV1 is a non-selective cation channel that can be activated by noxious heat (>42°C), extracellular protons (pH < 6) and endogenous and exogenous ligands (e.g. anandamide, N-arachidonoyl dopamine, capsaicin and resiniferatoxin) [3–7]. The TRPV1 channel is highly expressed in small and medium diameter sensory fibres of spinal and cranial nerves, as well as in several brain regions involved in perception of pain [8–10].

Accumulating evidence indicates that the TRPV1 channel is involved in body temperature regulation [11, 12]. TRPV1 agonists decrease body temperature in experimental animals [13–15], whereas such an effect is lacking in TRPV1 knockout mice [16]. Conversely, potent TRPV1 antagonists induce hyperthermia in experimental animals [11, 12, 17]. The TRPV1 channel is hypothesized to be tonically activated in vivo. This activation suppresses body temperature and maintains it at its normal level [11, 12]. Consequently, inhibition of the TRPV1 mediated tonic temperature suppression, through TRPV1 antagonism or desensitization, results in hyperthermia [12]. The hyperthermic effect of TRPV1 antagonism is postulated to be mediated via activation of thermogenesis and reduction of heat loss through constriction of the blood vessels in the skin [11, 12]. The hyperthermic effect of TRPV1 antagonism raised concerns regarding validity of this mechanism as a therapeutic target. This concern was alleviated with the observation that temperature elevation with TRPV1 antagonism attenuated with repeated administration in experimental animals [18, 19]. Several TRPV1 antagonists have been evaluated in humans [1, 20]. The reported effects of these antagonists ranged from mild temperature elevations that appeared to attenuate over time [2, 20, 21] to sustained pronounced temperature elevations that halted clinical development [22].

ABT-102, or (R)-(5-tert-butyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl)-3-(1H-indazol-4-yl)-urea, is a potent (IC50 1–16 nm) and selective TRPV1 antagonist which reversibly inhibits TRPV1 activation by a variety of stimuli (such as capsaicin, N-arachidonyl dopamine, anandamide, protons and heat) [23]. ABT-102 is efficacious in preclinical models of inflammatory, osteoarthritic, post-operative and bone cancer pain [18, 24]. With regard to its effects on body temperature, ABT-102 induced mild hyperthermia in rats which tolerated within 2 days of repeated dosing [18]. In humans, ABT-102 had a modest effect on body temperature and this effect appeared to tolerate by day 7 of dosing [25, 26].

We present in this report a thorough population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analysis of the effects of ABT-102 on body temperature in humans; comprising a relatively large dataset from three phase 1 trials where body temperature was extensively monitored during ABT-102 treatment (single and repeated administration) and washout in each subject. The analysis characterized the relationship between systemic exposure to ABT-102 and body temperature elevation including the time course of ABT-102 induced body temperature elevation and tolerance development to such an effect. By quantitatively integrating available information across many variables, this analysis is very powerful and key in evaluating the risks associated with ABT-102 body temperature effects in humans. Without such analysis, clinical decision making is left with separate and incomplete pieces of information represented by numerical estimates of low precision from small numbers of subjects evaluated at each dose level, in separate studies, and using different formulations that are associated with different systemic exposures.

As part of the analysis, we also quantitatively characterized the circadian rhythm in body temperature in humans including the impact of method of temperature measurement on interpretation of the data. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive quantitative PK/PD analysis of the effects of a TRPV1 antagonist on body temperature in humans published to date.

Methods

Study designs

The effects of ABT-102 on body temperature following single and multiple dosing were assessed in three double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group studies of the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of ABT-102 in healthy human volunteers. Study 1 evaluated five escalating single doses (2, 6, 18, 30 and 40 mg, oral solution formulation of ABT-102). Forty-five subjects (nine subjects per dose group) in general good health participated in this study. Study 2 evaluated three escalating multiple dose levels (2, 4 and 8 mg or matching placebo twice daily for 7 days, oral solution formulation of ABT-102). Twenty-seven subjects (nine subjects per dose group) in general good health participated in this study. Study 3 evaluated three multiple dose levels (1, 2 and 4 mg or matching placebo twice daily for 7 days, solid dispersion formulation of ABT-102). Thirty-six subjects (12 subjects per dose group) in general good health participated in this study. Subjects were randomized to ABT-102 or placebo with a 2:1 ratio in each dose group in all three studies.

All studies were conducted in accordance with all applicable regulatory and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and following the ethical principles originating in the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects provided written informed consent before enrolment and the study protocols were approved by independent ethics committees/review boards. Additional details regarding the study designs, inclusion and exclusion criteria for subject enrolment, study sites, ethics committees and drug administration procedures have been previously reported and the reader is referred to this report for such details 25.

Body temperature measurements

Serial measurements of oral or core body temperatures were obtained in the three phase 1 studies of ABT-102 as follows:

Study 1 (single dosing with solution formulation): oral body temperature was measured prior to dosing (0 h) and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 and 24 h following dosing on study day 1, every 8 h during ABT-102 washout (study days 2 and 3), and prior to discharge on study day 4.

Study 2 (multiple twice daily dosing with solution formulation for 7 days): oral body temperature was measured prior to each morning dose (0 h), following each morning dose at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 12 h (prior to the evening dose) and approximately at 2 and 4 h following each evening dose. Additionally, oral body temperature was measured every 8 h during ABT-102 washout (study days 8 and 9) and in the morning prior to subject discharge (study day 9) or upon subject discontinuation.

Study 3 (multiple twice daily dosing with solid dispersion formulation for 7 days): core body temperature was continuously recorded using VitalSense® Telemetric Physiological Monitoring System (Philips Healthcare, Andover, MA, USA) [26]. Subjects were required to swallow a temperature monitoring capsule. The capsule transmitted temperature readings to the small monitor worn by the subject. Each subject ingested one temperature capsule with approximately 60 ml of water 1 h prior to dosing on study day 1. Subsequently, subjects were required to ingest several temperature capsules during the study, and the number depended on the transit time (12 to 48 h, the temperature readings indicated when another temperature capsule needed to be ingested). Core body temperature values recorded for the following time points were extracted for analysis: every 30 min for the first 36 h after first dose, every 60 min from 36 to 72 h (study day 4) and every 4 h from study day 4 to study day 9.

Pharmacokinetic measurements

Serial blood samples for measurement of plasma ABT-102 concentrations were collected during ABT-102 treatment phase and washout in the three studies as has been previously described 25.

Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling

Sequential population PK/PD modelling [27] approach was used for analysis of the combined oral and core body temperature data from the three studies of ABT-102. The non-linear mixed effects modeling software nonmem (version VI; Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA) was used for the analysis. The empirical Bayesian individual PK parameter estimates from a previously reported population PK analysis of the three evaluated studies 25 were used as the PK component of ABT-102 body temperature PK/PD model. A user-defined subroutine (ADVAN6) was used to build the body temperature model with stepwise addition of parameters. The starting model consisted of three additive components: estimated baseline body temperature, circadian rhythm in body temperature and residual error. During model development, impact of the temperature measurement method (oral vs. core) on the baseline value, magnitude of circadian rhythm and residual error was evaluated and incorporated in the model. Most importantly, effect of ABT-102 exposure on body temperature and tolerance development to such an effect was characterized. Inter-subject variability in the model parameters was evaluated and the residual error model was optimized. The first order conditional estimation (FOCE) method with interaction between inter-subject variability and residual variability was used throughout the model building process.

Several criteria were used to evaluate the improvement in the model performance and to select the final model. The likelihood ratio test [27] was used for comparing rival hierarchical models where a decrease in nonmem objective function (–2 log likelihood) of 6.63 points was necessary to consider the improvement in model performance statistically significant at α = 0.01 and 1 degree of freedom. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used for comparing rival non-hierarchical models 28. Other selection criteria used included improved goodness of fit and residual plots, reduced variance of inter-subject and residual errors and increased precision in parameter estimation.

Model evaluation

The final model was evaluated using non-parametric bootstrap and visual predictive check. Non-parametric bootstrap was conducted to evaluate the robustness of the final model. One thousand datasets, each with the same number of subjects as the original dataset, were constructed by randomly sampling with replacement from the original dataset. The model was then fitted to the bootstrap datasets and all the model parameters were estimated. The median and 95th confidence interval (CI) (defined by the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles) for each parameter were then calculated from the successfully converging runs and compared to the point estimates from the original dataset.

Visual predictive check, stratified by study and dose level, was conducted to characterize whether the model replicates the features of the data from which it was built in simulations. The final model parameters were used to simulate 500 replicates of the observed data using nonmem. Additional simulation records were included in the dataset at intervals of sparse measurement to illustrate graphically the circadian rhythm pattern as characterized by the model. For calculation of summary statistics and graphing, time was rounded to the nearest hour and no additional binning of the data was performed.

For a dose level within a study, the median, 5th and 95th percentiles of simulated data within each replicate were calculated. Subsequently, the median value of these parameters across the 500 simulated replicates was determined and compared graphically to the median, 5th and 95th percentiles of observed data.

Results

A total of 7544 body temperature measurements [2696 oral measurements (studies 1 and 2) and 4848 core measurements (study 3)] were available from 108 subjects across the three studies. In study 3, a few core measurements recorded a sudden drop in temperature with quick recovery to the plausible human temperature range. These sudden fluctuations were believed to be artifacts that coincided with ingesting cold liquids, which impacted on the recording with the temperature monitoring capsules. Therefore, core temperature values below 34°C (approximately the minimum temperature observed with oral recordings from the two other studies) were excluded from the analysis dataset. Overall, 51 erroneous core measurements (approximately 1% of the total core temperature recordings) were excluded. The excluded core measurements ranged from 14.0 to 33.4°C with mean and median values of 25.3 and 24.1°C, respectively.

The final analysis dataset consisted of 7493 temperature (2696 oral and 4797 core) measurements. The oral temperature measurements ranged from 34.3 to 38.4°C with mean and median values of 36.5 and 36.4°C, respectively. The core temperature measurements ranged from 34.0 to 38.7°C, with mean and median value of 37.2°C in the final dataset.

The demographics and disposition of the 108 subjects who participated in the three analyzed studies have been previously reported 25.

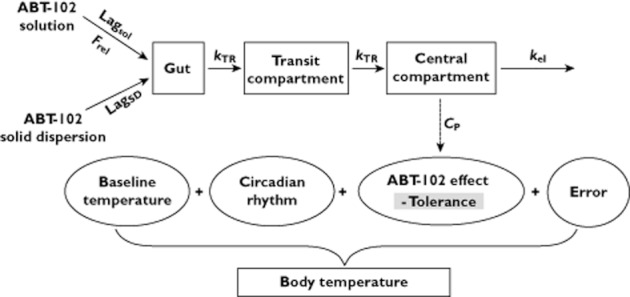

ABT-102 body temperature PK/PD model

The PK component of the model was a one compartment model with a transit compartment for absorption, first order elimination and formulation-dependent lag times and a bioavailability factor (Frel) for solution relative to solid dispersion formulation. The PK model was previously described in details 25. The population parameter estimates (95% bootstrap CIs) for the PK model were: oral clearance 16 (14, 18) l h−1, oral volume of distribution 215 (192, 237) l, transit rate constant 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) h−1, solid dispersion lag 0.6 (0.5, 0.8) h, solution lag 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) h and solution Frel 40 (35, 45) %. The inter-subject variability estimates were 33% for clearance, 24% for volume of distribution, 44% for absorption transit rate and 49% for the lag time. The PK model is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustrative diagram of ABT-102 body temperature PK/PD model. The PK component is a one-compartment model with a transit compartment for absorption, first-order elimination, and formulation-dependent lag-times and a bioavailability factor (Frel) for solution relative to solid-dispersion (SD) formulation. The PD model consists of additive components of baseline, circadian rhythm, ABT-102 effect [Emax function of plasma concentration (CP)] with tolerance development (decrease in ABT-102 Emax over time) and residual error. The baseline body temperature, circadian rhythm and residual error are measurement-type (core vs. oral) dependent

The key steps in the PD model building history and the associated improvement in the model performance as assessed by changes in nonmem objective function (ΔOF) is summarized in Table 1. The starting model consisted of three additive components: (i) estimated baseline body temperature (with inter-subject variability), (ii) circadian rhythm characterized by the amplitude and phase shift of a cosine function of time and (iii) additive residual error. This was based on prior analyses of individual studies of ABT-102. During model building, estimation of inter-subject variability for the amplitude then the phase shift of the circadian rhythm significantly improved the model fit (sequential ΔOF = −214 and −189, respectively). Estimation of a different baseline values for oral vs. core temperature measurement (with common inter-subject variance) further improved the model fit (ΔOF = −95). Estimation of measurement-type dependent inter-subject variance for baseline did not improve the fit any further. Effect of ABT-102 exposure (model-estimated plasma concentrations at time of temperature measurement) on body temperature was then included in the model as a fourth additive component using an Emax function of plasma exposure. As expected, inclusion of the Emax model resulted in a very significant improvement in the model fit (ΔOF = −677). Subsequently, tolerance development to ABT-102 effect was built into the model. Several tolerance models [29] were evaluated and in the final model tolerance to ABT-102 body temperature effect was driven by time such that ABT-102 Emax was allowed to decrease over time (mathematical coding described in the equations below). Inclusion of the tolerance component in the Emax model greatly improved the model fit (ΔOF = −1061). Inclusion of a link or biophase compartment to account for any possible delay in the initial temperature effect of ABT-102 was not significant, in agreement with visual inspection of the time course of ABT-102 exposure and its initial temperature effect. Estimation of inter-subject variability for tolerance half-time for ABT-102 EC50 improved the model fit (sequential ΔOF = −53 and −77, respectively). Subsequent inclusion of the type of temperature measurement (oral vs. core) as a covariate on the additive residual error was also significant (ΔOF = −60). The residual error model was further optimized by including an inverse proportional residual error component (higher error for lower observed temperatures; ΔOF = −1466). Finally, inclusion of the type of body temperature measurement as a covariate on the amplitude of the circadian rhythm slightly improved the model fit (ΔOF = −8). Other variables (such as baseline or gender) were examined as covariates for the different model parameters and were not found to be significant. The final body temperature model is depicted in Figure 1 and is summarized by the following four equations

Table 1.

The key steps of the PK/PD model building history and associated changes in nonmem objective function (OF)

| Model | Description | OF* | Δ OF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Estimated baseline body temperature with inter-subject variability (ISV); additive circadian rhythm (cosine function of time); additive residual error | −7 787 | – |

| Model 2 | Model 1 with ISV estimated on the amplitude of circadian rhythm | −8 001 | −214 |

| Model 3 | Model 2 with ISV estimated on the phase-shift of circadian rhythm | −8 190 | −189 |

| Model 4 | Model 3 with different baselines for core vs. oral body temperature; same ISV variance | −8 285 | −95 |

| Model 5 | Model 4 with additive ABT-102 effect (Emax function of plasma concentration) | −8 962 | −677 |

| Model 6 | Model 5 with tolerance to ABT-102 effect coded as decrease in ABT-102 Emax over time | −10 023 | −1061 |

| Model 7 | Model 6 with ISV on tolerance T50 | −10 076 | −53 |

| Model 8 | Model 7 with ISV on ABT-102 EC50 | −10 153 | −77 |

| Model 9 | Model 8 with different additive residual error variances for core vs. oral temperature measurements | −10 213 | −60 |

| Model 10 | Model 9 with combined additive and inverse-proportional residual error models for each type of temperature measurements | −11 679 | −1466 |

| Final model | Model 10 with different circadian rhythm amplitudes for oral vs. core temperature measurements; same ISV variance | −11 687 | −8 |

OF: nonmem objective function.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where Emax is the maximal effect of ABT-102 on body temperature (subject independent). For subject i, BTkij is the observed body temperatures at time j (Tj) with measurement type (i.e. core or oral) k; BLki is the baseline body temperature with measurement-type k; CRkij is the circadian rhythm effect at time j with measurement-type k; AMPki is the amplitude of circadian rhythm with measurement-type k; PSi is the phase shift for the circadian rhythm; DEij is ABT-102 effect on body temperature at time j; T50i is the time at which ABT-102 Emax decreases to half its initial value due to tolerance development; EC50i is ABT-102 plasma concentration at which half Emax is achieved; CPij is ABT-102 model-estimated plasma concentration at time j; Reskij is the residual random error at time j with measurement type k {combined additive and inverse proportional residual error models [ ; εn ∼ N(0,

; εn ∼ N(0, )]}, note that temperature values in the dataset were within the 34 to 39°C range.

)]}, note that temperature values in the dataset were within the 34 to 39°C range.

Inter-subject variability in the baseline and amplitude and phase shift of the circadian rhythm were estimated using additive error models [for parameter x, Px = TVPx + ηPxi, ηPxi ∼ N (0, )], while inter-subject variability in EC50 and T50 were estimated using exponential error models [for parameter y, Py = TVPy.exp(ηPyi), ηPyi ∼ N (0,

)], while inter-subject variability in EC50 and T50 were estimated using exponential error models [for parameter y, Py = TVPy.exp(ηPyi), ηPyi ∼ N (0, )]. nonmem code for the final model is presented in Appendix S1 online.

)]. nonmem code for the final model is presented in Appendix S1 online.

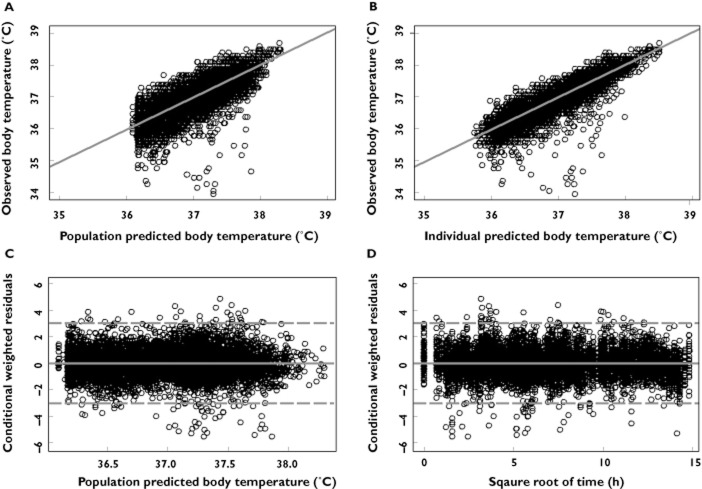

Parameter estimates from the final population PK/PD model along with their associated % relative standard errors (% RSE) are presented in Table 2. All parameters of the model were estimated with good precision (% relative standard error less ≤17% for fixed effects and ≤31% for random effects). Diagnostic plots for the final model are presented in Figure 2A–D. Scatter plots of population predicted vs. observed body temperature (Figure 2A) showed symmetric distribution around the line of identity. In addition, there was good agreement between observed and individual predicted body temperatures (Figure 2B), indicating that the model fitted the data well at the population and individual subjects levels. Scatter plots of the conditional weighted residuals [30] vs. population predicted body temperature or square root of time did not show any discernable pattern indicating lack of any systematic bias in the model fit across the body temperature range or duration of treatment.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates and results of the bootstrap evaluation of ABT-102 body temperature PK/PD model

| Parameter | Point estimate (%RSE)* | Bootstrap median [95% CI]† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Oral (°C) | 36.3 (0.1) | 36.3 (36.3–36.4) |

| Core (°C) | 37.0 (0.1) | 37.0 (37.0–37.1) | |

| Circadian rhythm amplitude | Oral (°C) | 0.25 (6) | 0.25 (0.22–0.28) |

| Core (°C) | 0.31 (5) | 0.31 (0.28–0.34) | |

| Circadian rhythm phase-shift (h) | 7.6 (2) | 7.6 (7.3–7.9) | |

| ABT-102 Emax (°C) | 2.2 (8) | 2.2 (1.9–2.7) | |

| ABT-102 EC50 (ng ml−1) | 20 (15) | 20 (15–28) | |

| Tolerance T50 (h) | 28 (17) | 28 (20–43) | |

| ω2Baseline | 0.05 (15) | 0.05 (0.03–0.06) | |

| ω2Amplitude | 0.008 (21) | 0.008 (0.005–0.011) | |

| ω2Phase-shift | 1.57 (18) | 1.55 (1.05–2.15) | |

| ω2EC50 | 0.34 (28) | 0.32 (0.18–0.53) | |

| ω2Tolerance-T50 | 0.69 (31) | 0.68 (0.32–1.35) | |

| Res Error σ21 | Oral | 0.22 (13) | 0.22 (0.16–0.28) |

| Core | 0.33 (11) | 0.33 (0.26–0.40) | |

| Res Error σ22 | Oral | 0.04 (15) | 0.04 (0.03–0.05) |

| Core | 0.02 (15) | 0.02 (0.01–0.02) | |

nonmem point estimate and the associated % relative standard error (% RSE).

The median and 95% confidence interval (2.5th and 97.5th percentiles) calculated from the parameter estimates of the successfully converging bootstrap datasets (1000 out of 1000).

Figure 2.

Diagnostic plots of the final body temperature PK/PD model of ABT-102. (A) observed vs. population predicted body temperature; (B) observed vs. individual predicted body temperature; (C) conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) vs. population predicted body temperature; (D) conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) vs. square root of time. Solid lines represent lines of identity in (A) and (B) and zero conditional residuals in (C) and (D). Dashed lines represent ± 3 SD in (c) and (d)

Model evaluation

The final model successfully converged for the 1000 bootstrap datasets. Results of the bootstrap evaluation of the population PK/PD model are presented in Table 2. The bootstrap evaluation indicates that the model was highly robust with almost perfect agreement between median values of the parameters estimates from 1000 bootstrap datasets and the point estimate from the original dataset. Additionally, the bootstrap confidence intervals for the parameter estimates, established with the 1000 bootstrap datasets, were fairly tight indicating high precision in the parameter estimates, in agreement with the small relative standard error estimated parametrically with nonmem.

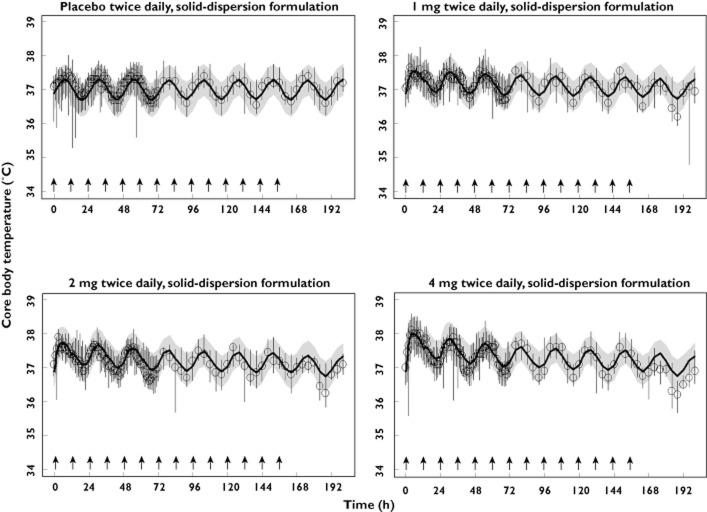

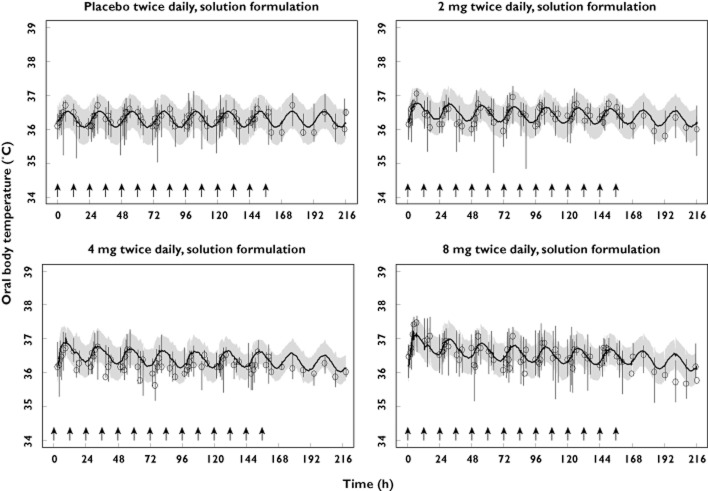

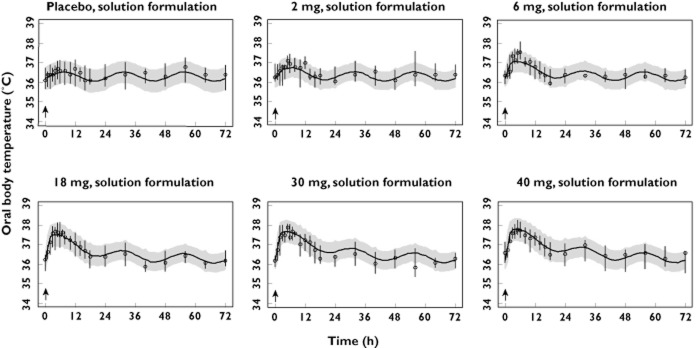

The results of the visual predictive check of the final model, stratified by study and dose level are presented in Figures 3–5, where the median, 5th and 95th percentiles of observed data are compared with the median, 5th and 95th percentiles of the simulated data (median parameters from 500 simulated replicates). Visual predictive check indicted that the model replicates the features of the data from which it was built in simulation and reveals adequacy of the model in capturing both the magnitude of effect across single and multiple dosing as well as the time course of the temperature effects (Figures 5) and tolerance development to such effects (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Visual predictive check, stratified by dose, of the observed and model-simulated oral body temperature for study 1. Circles represent observed medians. Error bars represent observed 5th to 95th percentiles. Solid lines represent the model-simulated medians. Shaded areas represent the model simulated 5th to 95th percentiles. Arrows indicate times of dosing

Figure 5.

Visual predictive check, stratified by dose, of the observed and model-simulated core body temperature for study 3. Circles represent observed medians. Error bars represent observed 5th to 95th percentiles. Solid lines represent the model-simulated medians. Shaded areas represent the model simulated 5th to 95th percentiles. Arrows indicate times of dosing

Figure 4.

Visual predictive check, stratified by dose, of the observed and final model-simulated oral body temperature for study 2. Circles represent observed medians. Error bars represent observed 5th to 95th percentiles. Solid lines represent the model-simulated medians. Shaded areas represent the model simulated 5th to 95th percentiles. Arrows indicate times of dosing

Safety summary

Details of ABT-102 safety in phase 1 studies has been reported elsewhere [26]. In general, ABT-102 was safe and adequately tolerated in healthy volunteers. Consistent with other TRPV-1 antagonists, the safety profile of ABT-102 was mainly characterized by fully reversible dose-dependent impairment of thermal sensation, and the most frequently reported adverse events were sensations of feeling hot or cold, hot flushes, altered taste sensation and oral hypoesthesias or dysesthesias.

The body temperature increases induced by ABT-102 did not exceed 39°C in any study and no subject was discontinued from the studies or required any medical intervention due to elevated body temperatures. No other relevant neurological, cardiovascular or general side effects were reported.

Discussion

We present in this report a non-linear mixed effects PK/PD analysis of the effects of ABT-102, a potent and selective TRPV1 antagonist, on body temperature in humans. The analysis was based on a combined dataset from three phase 1 trials where body temperature was extensively monitored during ABT-102 administration and washout. The analysis integrates available information on ABT-102 body temperature effect across studies, exposures (entire dose and concentration ranges evaluated in humans), time relative to administration (single and repeated dosing, tolerance development and drug washout) and method of temperature measurement (measurements using oral thermometers or telemetric monitoring through ingested capsules). To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive quantitative exposure–response analysis of the effects of a TRPV1 antagonist on body temperature in humans published to date.

The developed body temperature model consists of two sets of parameters: (i) system parameters characterizing the circadian rhythm and variability in body temperature in humans as well as impact of method of temperature measurement on such parameters and (ii) drug parameters characterizing the relationship between ABT-102 exposure and its body temperature effect as well as the time course of tolerance development to such an effect. Impact of ABT-102 formulation (solution vs. solid dispersion) was already accounted for in the PK model as previously described 25, where the solution formulation had lower bioavailability (∼40%) relative to the solid-dispersion formulation and a shorter lag time (0.3 h for the solution formulation and 0.6 h for the solid dispersion formulation). No differences between the two formulations in the body temperature effect were distinguishable once the differences in exposure were accounted for.

Results of the present analysis indicate a highly significant relationship between ABT-102 plasma concentrations and an initial transient increase in body temperature in humans as evidenced by the large drop in the objective function with inclusion of drug effect in the model (Table 1). The estimated maximum ABT-102 induced temperature increase was 2.2°C with plasma EC50 value of 20 ng ml−1 (Table 2). The between-subject variability in ABT-102 potency (EC50) was 58%. Since time is a covariate on ABT-102 Emax as discussed below, at pharmacokinetic tmax (∼4 h post-dose), the model estimated maximal initial effect is 1.9°C. At the highest evaluated exposure of ABT-102 in humans (40 mg single dose, mean Cmax 73 ng ml−1) 25, the model estimated mean increase in body temperature is 1.5°C at tmax.

The estimated EC50 value for ABT-102 temperature effect in humans (20 ng ml−1) is comparable with the plasma concentrations associated with chronic 50% efficacy in preclinical models of pain and is 5- to 13-fold below the plasma concentrations associated with acute 50% efficacy in these preclinical models [18]. In a recent experimental pain study in healthy human volunteers, 6 mg single dose of ABT-102 (Cmax, 15 ng ml−1, Caverage during experiment, 9 ng ml−1) demonstrated superior anti-nociceptive efficacy to etoricoxib and tramadol 31. Taken together, the model estimated transient body temperature increase is estimated to be 0.6 to 0.8°C at ABT-102 analgesic exposures in humans.

ABT-102 body temperature effect dissipated with time (Figures 4 and 5) despite continued twice daily dosing and two-fold accumulation in exposure 25, indicating tolerance development. In the PK/PD model, a tolerance component was included where ABT-102 Emax was allowed to decrease over time (tolerance driven by time). Inclusion of the tolerance component greatly improved the model fit (Table 1). The time for ABT-102 Emax to decrease to half its initial value (i.e. T50) was estimated to be 28 h since administration of the first ABT-102 dose (with between subject variability of 83%). Alternative empirical tolerance models, such as models where tolerance is driven by the drug concentration through delayed non-competitive antagonism 32, delayed partial agnosim [33] or delayed inverse agonism [29, 34] were evaluated. Relative to the selected time-driven tolerance model, alternative concentration-driven models either provided low precision in parameter estimates (non-competitive antagonist model), higher objective function (partial agonist model) or under-estimated the effect of the 30 and 40 mg single doses (reverse agonist model, data not shown). Visual inspection of the data suggested the possibility of a slight rebound effect (decrease in body temperature below baseline) after ABT-102 washout (Figures 4 and 5, note that observed medians were below the model predicted medians for washout measurements at highest doses). Alternative tolerance models that allow for rebound were not able to capture this small rebound effect (for example the delayed-inverse agonist model [29, 34] estimated comparable maximum drug effect and opposing tolerance effect and suffered other limitations, data not shown).

With regard to the system parameters, the model estimates that temperature recording is 0.7°C higher for measurement with ingested telemetric capsule than for measurement with oral thermometer (estimated baseline values of 37.0 vs. 36.3°C, respectively). This difference is physiologically plausible. Fluctuation in body temperature due to circadian rhythm (twice the estimated amplitude) is approximately 0.5 to 0.6°C (oral vs. core) with the highest temperature recorded at approximately 15:40 o'clock (7.6 h phase shift for cosine function relative to dosing; dosing typically performed 08:00 o'clock in these phase 1 trials). As expected for body temperature, the between subject variance is estimated to be very small (standard deviation for baseline and amplitude of circadian rhythm of approximately of 0.2 and 0.1°C, respectively).

The majority of the apparently erroneous temperature measurements appeared to be of low values in the present dataset (note sudden dips in observed 5th percentile in Figures 4 and 5). This is not surprising since erroneous measurements would be mostly due incomplete equilibrium of the temperature measuring device with the body (due to brief or inappropriate positioning of oral thermometer under the tongue or effect of ingested cold liquids on temperature recording capsule) leading to low measurement. Therefore, a combined additive and inverse proportional residual error was used in the final model. In this model, higher absolute error was assumed for low body temperature measurements than in high measurements. This error model significantly improved the fit to the data (Table 1). Core telemetric temperature measurements below 34°C, the lowest measurement with oral recording, were censored in the present analysis. Censoring both the oral and core measurements at a higher cut-off (for example at 35°C) could have been applied as an alternative to using the inverse proportional error model. This censoring approach was undesirable since there was no objective way of selecting the cut-off.

Diagnostic plots (Figure 2a–D), bootstrap evaluation (Table 2) and visual predictive check (Figures 5) of the model developed in the present analysis indicated that the model described the data well, was highly robust and replicated the features of the data from which it was developed in stochastic simulations across doses, regimens, body temperature range and duration of treatment.

It may be speculated whether the analgesic effects of ABT-102 dissipate with repeated dosing, similar to its effects on body temperature. Repeated administration of ABT-102 for 5–12 days enhanced its analgesic activity in preclinical models of osteoarthritic, post-operative and bone cancer pain without accumulation of ABT-102 in plasma or brain [18]. Similar effects were observed with a structurally distinct TRPV1 antagonist, A-993610. On the contrary, the body temperature elevations induced by ABT-102 tolerated following repeated dosing over 2 days [18]. Therefore, in preclinical animals, it has been shown that the body temperature effects of TRPV1 receptor antagonists are attenuated following repeated administration while the analgesic activity is enhanced. This yet remains to be demonstrated in humans in robust chronic efficacy trials. ABT-102 potently and reversibly increased heat pain threshold and reduced painfulness of suprathreshold oral/cutaneous heat in healthy human volunteers in an experimental setting [26]. Unlike the body temperature effects, these thermosensory effects did not appear to tolerate with repeated dosing [26]. Overall these data suggest divergent down-stream pharmacology and differential tolerance/possible sensitization for the distinctive effects of TRPV1 antagonists in animals and humans.

The magnitude of temperature elevation induced by ABT-102 at the predicted therapeutic exposures, as robustly characterized in the present analysis from data across studies, suggests a limited clinical concern, in particular considering the relatively rapid tolerance development to such effect. However, it still needs to be assessed if there is a potential additive effect when this compound is administered in subjects with an already pre-existing temperature elevation, for example, in febrile inflammatory conditions. In addition, it has not been established, at this stage, if TRPV1 induced temperature elevations can be attenuated by administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or paracetamol. While more clinical trials that establish the efficacy and safety profiles of ABT-102 in different clinical settings are needed for a proper characterization of the risk to benefit ratio, it would ultimately be preferential to develop a TRPV1 antagonist lacking any effect on body temperature in humans.

In conclusion, in the present analysis, we characterized quantitatively the relationship between ABT-102 exposure and its transient effect on body temperature in humans using a non-linear mixed-effects modelling approach. We also characterized the time course of tolerance development to the ABT-102 effect. At the projected ABT-102 analgesic levels in humans, the model estimated effect on body temperature is 0.6 to 0.8°C and this effect tolerates within 2–3 days of dosing. As part of the analysis, we also characterized quantitatively the circadian rhythm in body temperature in humans including the impact of the method of temperature measurement on interpretation of data.

Competing Interests

The studies presented in this manuscript were funded by Abbott Laboratories. All authors are employees and share holders of Abbott Laboratories and the authors declare no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Appendix S1

NONMEM code for ABT-102 body temperature PK/PD model

References

- 1.Moran MM, McAlexander MA, Biro T, Szallasi A. Transient receptor potential channels as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:601–620. doi: 10.1038/nrd3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Round P, Priestley A, Robinson J. An investigation of the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel TRPV1 antagonist XEN-D0501 in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:921–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Jerman JC, Nasir S, Gray J, Muir AI, Chambers JK, Randall AD, Davis JB. The endogenous lipid anandamide is a full agonist at the human vanilloid receptor (hVR1) Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:227–230. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SM, Bisogno T, Trevisani M, Al-Hayani A, De Petrocellis L, Fezza F, Tognetto M, Petros TJ, Krey JF, Chu CJ, Miller JD, Davies SN, Geppetti P, Walker JM, Di Marzo V. An endogenous capsaicin-like substance with high potency at recombinant and native vanilloid VR1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8400–8405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122196999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang H-H, Prescott ED, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt S-E, Basbaum AI, Chao MV, Julius D. Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature. 2001;411:957–962. doi: 10.1038/35082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caterina MJ. Vanilloid receptors take a TRP beyond the sensory afferent. Pain. 2003;105:5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tominaga M, Caterina MJ. Thermosensation and pain. J Neurobiol. 2004;61:3–12. doi: 10.1002/neu.20079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavva NR, Bannon AW, Surapaneni S, Hovland DN, Jr, Lehto SG, Gore A, Juan T, Deng H, Han B, Klionsky L, Kuang R, Le A, Tamir R, Wang J, Youngblood B, Zhu D, Norman MH, Magal E, Treanor JJ, Louis JC. The vanilloid receptor TRPV1 is tonically activated in vivo and involved in body temperature regulation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3366–3374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4833-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner AA, Turek VF, Almeida MC, Burmeister JJ, Oliveira DL, Roberts JL, Bannon AW, Norman MH, Louis JC, Treanor JJ, Gavva NR, Romanovsky AA. Nonthermal activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 channels in abdominal viscera tonically inhibits autonomic cold-defense effectors. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7459–7468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1483-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dogan MD, Patel S, Rudaya AY, Steiner AA, Szekely M, Romanovsky AA. Lipopolysaccharide fever is initiated via a capsaicin-sensitive mechanism independent of the subtype-1 vanilloid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:1023–1032. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almeida MC, Steiner AA, Branco LG, Romanovsky AA. Cold-seeking behavior as a thermoregulatory strategy in systemic inflammation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:3359–3367. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hori T. Capsaicin and central control of thermoregulation. Pharmacol Ther. 1984;26:389–416. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(84)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanson DM, Dubin AE, Shah C, Nasser N, Chang L, Dax SL, Jetter M, Breitenbucher JG, Liu C, Mazur C, Lord B, Gonzales L, Hoey K, Rizzolio M, Bogenstaetter M, Codd EE, Lee DH, Zhang SP, Chaplan SR, Carruthers NI. Identification and biological evaluation of 4-(3-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylic acid (5-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-yl)amide, a high affinity TRPV1 (VR1) vanilloid receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1857–1872. doi: 10.1021/jm0495071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honore P, Chandran P, Hernandez G, Gauvin DM, Mikusa JP, Zhong C, Joshi SK, Ghilardi JR, Sevcik MA, Fryer RM, Segreti JA, Banfor PN, Marsh K, Neelands T, Bayburt E, Daanen JF, Gomtsyan A, Lee CH, Kort ME, Reilly RM, Surowy CS, Kym PR, Mantyh PW, Sullivan JP, Jarvis MF, Faltynek CR. Repeated dosing of ABT-102, a potent and selective TRPV1 antagonist, enhances TRPV1-mediated analgesic activity in rodents, but attenuates antagonist-induced hyperthermia. Pain. 2009;142:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavva NR, Bannon AW, Hovland DN, Jr, Lehto SG, Klionsky L, Surapaneni S, Immke DC, Henley C, Arik L, Bak A, Davis J, Ernst N, Hever G, Kuang R, Shi L, Tamir R, Wang J, Wang W, Zajic G, Zhu D, Norman MH, Louis JC, Magal E, Treanor JJ. Repeated administration of vanilloid receptor TRPV1 antagonists attenuates hyperthermia elicited by TRPV1 blockade. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:128–137. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.125674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunthorpe MJ, Chizh BA. Clinical development of TRPV1 antagonists: targeting a pivotal point in the pain pathway. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krarup AL, Ny L, Astrand M, Bajor A, Hvid-Jensen F, Hansen MB, Simren M, Funch-Jensen P, Drewes AM. Randomised clinical trial: the efficacy of a transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonist AZD1386 in human oesophageal pain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1113–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gavva NR, Treanor JJ, Garami A, Fang L, Surapaneni S, Akrami A, Alvarez F, Bak A, Darling M, Gore A, Jang GR, Kesslak JP, Ni L, Norman MH, Palluconi G, Rose MJ, Salfi M, Tan E, Romanovsky AA, Banfield C, Davar G. Pharmacological blockade of the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 elicits marked hyperthermia in humans. Pain. 2008;136:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Surowy CS, Neelands TR, Bianchi BR, McGaraughty S, El Kouhen R, Han P, Chu KL, McDonald HA, Vos M, Niforatos W, Bayburt EK, Gomtsyan A, Lee CH, Honore P, Sullivan JP, Jarvis MF, Faltynek CR. (R)-(5-tert-butyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl)-3-(1H-indazol-4-yl)-urea (ABT-102) blocks polymodal activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptors in vitro and heat-evoked firing of spinal dorsal horn neurons in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:879–888. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.138511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomtsyan A, Bayburt EK, Schmidt RG, Surowy CS, Honore P, Marsh KC, Hannick SM, McDonald HA, Wetter JM, Sullivan JP, Jarvis MF, Faltynek CR, Lee C-H. Identification of (R)-1-(5-tert-Butyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-yl)-3-(1H-indazol-4-yl)urea (ABT-102) as a potent TRPV1 antagonist for pain management. J Med Chem. 2008;51:392–395. doi: 10.1021/jm701007g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Othman AA, Nothaft W, Awni WM, Dutta S. Pharmacokinetics of the TRPV1 antagonist ABT-102 in healthy human volunteers: population analysis of data from 3 phase 1 trials. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:1028–1041. doi: 10.1177/0091270011407497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowbotham MC, Nothaft W, Duan WR, Wang Y, Faltynek C, McGaraughty S, Chu KL, Svensson P. Oral and cutaneous thermosensory profile of selective TRPV1 inhibition by ABT-102 in a randomized healthy volunteer trial. Pain. 2011;152:1192–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheiner LB, Ludden TM. Population pharmacokinetics/dynamics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:185–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.001153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beal SL, Sheiner LB. NONMEM Users Guide. San Francisco, CA: Division of Clinical Pharmacology, University of California; 1979. Part V. –1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardmark M, Brynne L, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Karlsson MO. Interchangeability and predictive performance of empirical tolerance models. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:145–167. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hooker AC, Staatz CE, Karlsson MO. Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES): a model diagnostic for the FOCE method. Pharm Res. 2007;24:2187–2197. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaffler K, Reeh P, Duan WR, Best AE, Othman AA, Faltynek CR, Locke C, Nothaft W. An oral TRPV1 antagonist attenuates laser radiant-heat-evoked potentials and pain ratings from UVB-inflamed and normal skin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04377.x. Accepted Article doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04377.x, Epub: 2012 Jul 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porchet HC, Benowitz NL, Sheiner LB. Pharmacodynamic model of tolerance: application to nicotine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ouellet DM, Pollack GM. A pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic model of tolerance to morphine analgesia during infusion in rats. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1995;23:531–549. doi: 10.1007/BF02353460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardmark M, Ekblom M, Bouw R, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. Quantification of effect delay and acute tolerance development to morphine in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:1061–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.