Abstract

Objective

To examine the patterns of weight loss behaviour and the association between weight loss attempts with actual weight status and children's and parental perceptions of weight status.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

Karnataka, South India.

Participants

1874 girls and boys aged 8–14 years from seven schools in Karnataka, South India.

Main outcome measures

The association between weight loss attempts and sociodemographic factors, weight status and the child's or the parent's perception of weight status.

Results

Approximately 73% of overweight and obese, 35% of normal weight and 22% of underweight children attempted to lose weight. Children of lower socioeconomic groups studying in schools in the local vernacular and overweight/obese children were more likely to attempt to lose weight (adjusted OR ie, AOR=1.57, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.25; AOR=4.38, 95% CI 2.64 to 7.28, respectively). Perception of weight status was associated with weight loss attempts. Thus, children who were of normal weight but perceived themselves to be overweight/obese were three times more likely to attempt weight loss compared with those who accurately perceived themselves as being of normal weight, while the odds of attempting weight loss were the highest for those who were overweight and perceived themselves to be so (AOR∼18).

Conclusions

Children are likely to attempt weight loss in India irrespective of their weight status, age and gender. Children who were actually overweight as well as those who were perceived by themselves or by their parents to be overweight or obese were highly likely to try to lose weight. It is necessary to understand body weight perceptions in communities with a dual burden of being overweight and undernourished, if intervention programmes for either are to be successful.

Keywords: Public Health, Epidemiology, Cross Sectional Study, India

Article summary.

Article focus

To explore weight loss behaviour patterns and association between weight loss attempts with sociodemographic factors, actual as well as children's and parental perceptions of child's weight status.

Key messages

In India, where both overweight and underweight children coexist; there are no data on the associations of body weight perceptions of children in relation to weight loss attempts. It is essential to understand this association to tailor suitable intervention programmes that can work in communities with concurrent undernutrition and overnutrition.

Weight loss is attempted by children irrespective of weight status, age and gender. However, there are higher odds of attempting to lose weight among those who perceive themselves to be overweight, although their weight status may be normal.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to report perceptions of body weight in India in relation to weight loss attempts.

The cross-sectional study design used in this study allows only associations to be assessed.

Introduction

Body image is a psychosocial dimension of body size that encompasses both perceptual and attitudinal factors1 and has been associated with eating disorders.1 2 In recent years, its association with overweight and obesity has been described.3 It is recognised that individuals make decisions on lifestyle behaviours based on body weight perceptions (a dimension of body image).1 4 In India, there is a large burden of undernutrition alongside increasing overweight and obesity.4 For public health and clinical programmes to be more effective, body image of undernourished and overweight children should be understood in the context of the influence of culture on body weight perceptions and on weight management behaviours.

A large number of studies have indicated that children and adolescents misperceive their body weight status.5–10 Interventions that address sociocultural attitudes towards appearance should ideally reduce body image dissatisfaction as well as overweight and obesity since studies have indicated a relationship between body image, unhealthy eating practices and obesity.11 12 Perceptions of body weight are, in part, influenced by external factors including cultural norms and social preferences as it has been observed that Asian women have less body dissatisfaction than other ethnic groups.13 In India, it is often believed that an overweight person is wealthier and happier and reflects social mobility to a higher status compared to an underweight person, although there are no studies to corroborate this. The disconnect between actual weight and perception of body size could stem from the extent to which individuals identify with the majority cultural standards of beauty.14 There are also reports that individuals in less socioeconomically developed societies positively evaluate overweight and obese figures.6 Evidence also suggests associations of actual body weight, body weight perceptions and weight dissatisfaction with weight control practices; overweight children are more likely to try to lose weight compared to non-overweight children.7 15 Analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 16 and the Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System (YRBSS)14 17 indicate that those overweight children who perceived their weight status correctly were more likely to exercise or eat less for weight control. Results from an analysis from Europe, Israel and North America as part of the Health Behaviour in School aged Children (HBSC) 2001/2002 survey indicated that weight and age were significant factors associated with current attempts to lose weight.15

For healthy weight management it is necessary for a person to perceive his or her weight status accurately as well as be aware of healthy methods to lose or gain weight. Most literature on body weight perceptions and weight-control behaviours are related to studies carried out in developed countries5 7 14 16 with a few on ethnic minorities, including South Asians.3 10 The present analysis aims to examine the associations between the actual weight status, body weight perceptions of both children and their parents and body weight satisfaction with weight-loss intentions. The study sample included a wide range of body weights to reflect the dual burden of undernutrition and overweight/obesity that India currently faces.

Methods

Study population

A total of 2083 school children aged 8–14 years from seven schools of varying socioeconomic status (SES) located in rural areas, towns in Karnataka and urban Bangalore in South India, were contacted at baseline out of which 1907 (91.6%) children participated in a longitudinal study on body image perceptions and growth indices of school children, details of which have been published earlier.18 Convenience sampling of seven coeducational, non-residential schools was employed, such that children representing various SESs (based on school fees linked to the medium of instruction) were recruited. Of these schools, two were located in villages, three in small towns and two in Bangalore city. The schools in which Kannada, the regional state language, was the language of instruction, received government support and charged an annual tuition fees of  250–

250– 500 whereas English medium schools did not receive government support and charged an annual tuition fees of above

500 whereas English medium schools did not receive government support and charged an annual tuition fees of above  6000. Hence the medium of instruction in schools was used as an indicator of SES. Three schools (one each in a village, a small town and a city) had Kannada as the medium of instruction while four schools (one in a village, two in small towns and one in the city) had English as the medium of instruction.

6000. Hence the medium of instruction in schools was used as an indicator of SES. Three schools (one each in a village, a small town and a city) had Kannada as the medium of instruction while four schools (one in a village, two in small towns and one in the city) had English as the medium of instruction.

The sample recruited had adequate power (above 80%) to identify the significant sociodemographic predictors for perception of body image in the present study and to estimate a difference of at least 10% overestimation or underestimation of body weight at 5% level of significance. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board.

Principals of the schools were contacted for permission to conduct the study in their schools. A written parental consent and assent from the child was also obtained. A questionnaire to assess body image perception was administered by an investigator (MP) to all the consenting students in a class by reading aloud the questions in either English or Kannada (the local language). Responses were marked on the questionnaire by each child. A short questionnaire, in English or the local language to be filled by one of the parents, was sent home after the children completed their questionnaires in the school. Children whose parents were illiterate (6.7% mothers and 5.9% fathers), elicited the answers from either of their parents and filled up the questionnaire.

Measurements

Height was measured without foot wear using a fibreglass tape to 0.2 cm. Weight was measured in school uniforms but without shoes using a calibrated digital scale (Home Health, Model 8604, Dr Morepen Lab, Hong Kong) to the nearest 100 gm. All measurements were made using a standardised protocol. Body mass index (BMI) was computed and the BMI-for-age Z-score values were obtained using the WHO AnthroPlus software V.1.0.2 (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland). Children were then categorised by actual weight status as overweight (>+1 SD), normal (<−2 to +1 SD) and underweight (<−2 SD). These values at 19 years of age, at +1 SD correspond to the BMI values of 25.4 kg/m² for boys and 25 kg/m² for girls and is equivalent to the overweight cut-off for adults (>25 kg/m²), while the +2 SD value (29.7 kg/m² for both sexes) compares closely with the cut-off for obesity (>30 kg/m²).19

To assess current body weight perception, children were asked to mark whether they thought their body weight or appearance was ‘too thin’, ‘a little thin’, ‘normal’, ‘a little fat’ or ‘very fat’. Response to a similar identical question about their child's body weight or appearance with similar options was filled by parents in a questionnaire sent to their homes. For analysis, ‘very thin’ and ‘a little thin’ were combined as ‘too/little thin’ and ‘a little fat’ and ‘very fat’ were combined as ‘a little/too fat’ and ‘normal’ remained ‘normal’.

To assess perceptions on desired (ideal) body weight, children responded to the question ‘I want to be’ with options ‘a lot fatter’, ‘slightly fatter’, ‘as I am at present’, ‘slightly thinner’, ‘much thinner’. The first two options were clubbed as ‘a lot/slightly fatter’, ‘as I am at present’ as ‘same as at present’ and the last two options clubbed as ‘slightly/much thinner’. Parents responded to a similar question on ‘I want my child to be’ with an identical set of options. For analysis, clubbing of the options for parents’ desired body weight for their child was also performed in a similar manner.

The Stunkard's silhouettes20 were also used to assess body image perception in children and this was also administered in the classroom. To make comparisons with the body weight perception questions, the nine images were regrouped to reflect three categories of weight status: underweight, normal and overweight. The agreement between the perceived visual image and the body weight perception obtained by questions of current weight status, evaluated using κ statistics ranged from 0.23 to 0.53. A fair agreement between underweight/fat and normal and a moderate agreement between both the extremes of weight (underweight vs overweight) was seen. There were no gender differences in the agreement. Parental perceptions of the body weight were assessed using structured questions and since this was available for both parent and child; further analyses were carried out using only the questions.

In addition, children were asked whether they had ever tried to lose weight. If they replied in the affirmative (options: yes/no), the method used to try and lose weight was recorded as ‘skipping meals’, ‘stopped eating a certain kind of food’, ‘reduced quantity of food eaten’ and ‘exercise’ as a multiple response. Weight-loss methods recommended by parents were similarly recorded.

The present analysis is restricted to children on whom anthropometric measurements were available and who responded to the question on weight loss and this corresponds to 1874 participants (871 boys and 1003 girls). The response rate (of a total of 1907 children) was 98.3%; sociodemographic (age, gender and medium of instruction) characteristics between the responders and non-responders were comparable.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as number and percentages for all the categorical variables. For analysis, sociodemographic variables of age of children were categorised as 10 and below and above 10 years of age (the adolescent period),21 language of instruction as Kannada and English mediums (a surrogate of SES), location as city and non-city (village and small towns) and maternal and paternal education below seventh grade and above seventh grade.

Cross tabulations were created for actual weight status of the child with the child's perception and parent's perception of their child's current body weight. Using this, the following eight groups were formed. As there were no children who were underweight but were perceived by either themselves or their parents to be overweight, this category was not considered.

U/U—underweight by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be underweight.

U/N—underweight by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be normal.

N/U—normal by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be underweight.

N/N—normal by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be normal.

N/O—normal by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be overweight.

O/N—overweight by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be normal.

O/O—overweight by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be overweight.

O/U—overweight by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be underweight.

The referent group was the N/N group.

The association between the various sociodemographic factors as well as with the above eight groups and attempt to lose weight was evaluated using the χ2 test and the unadjusted OR are reported. Association between attempt to lose weight and child's actual weight status, child's and parent's perception of child's weight status and the aforementioned eight groups were performed using χ2 test stratified by age and gender. Binary logistic regression was performed to identify the factors associated with attempted weight loss adjusted for sociodemographic variables of age, gender, medium of instruction, parent's education and current actual body weight status, child's and parent's perceived and desired weight status of the child as model 1. In addition, a model (model 2) adjusted only for age, sex, medium of instruction, actual weight status and the child's weight perception was obtained. Binary logistic regression was also performed to identify the factors associated with attempting to lose weight (yes/no) based on the eight groups (detailed hereinbefore) created using the actual body weight status of the child and child's or parent's perception of child's weight, adjusted for age, gender and medium of instruction. A level of significance (two-sided) less than 5% was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 1907 study children, 1874 responded to the question on whether they had ever tried to lose weight. Of these, 65.5% of children were normal weight, 25% underweight and 9.5% overweight. A total of 32% of children perceived themselves to be underweight; this was 7% more than the actual prevalence of underweight. Similarly, 15.4% perceived themselves to be overweight (5.9% higher than the actual prevalence). In contrast, parents tended to underestimate underweight (5% lower than the actual prevalence of underweight).

A total of 35% of children had attempted to lose weight; this constituted 73% of overweight and obese, 35% of normal weight and 22% of underweight children. A total of 68% of those children who perceived themselves to be overweight, 32% of those who perceived themselves to be normal and 23% of those who perceived themselves to be underweight attempted to lose weight. Similarly, 54% of children whose parents perceived them to be overweight, 35% who perceived them to be normal and 21% of those who perceived them to be underweight attempted to lose weight. Correlations between the actual weight status of the child and the child's or parent's perception of the child's weight status, as well as the child's and the parent's perceptions of desired (ideal) body weight ranged from 0.12 to 0.31 (p<0.01) (see online supplementary table S1) indicating a low to moderate correlation between these variables.

Among the sociodemographic factors (table 1, model 1), children in schools with Kannada as the medium of instruction were more likely to attempt to lose weight than those studying in schools with English as the medium of instruction (adjusted OR, ie, AOR=1.57, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.25). Underweight children were less likely to try to lose weight (AOR=0.71, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.98), while overweight/obese children were more likely (AOR=4.38, 95% CI 2.64 to 7.28) to try and lose weight compared to normal weight children. Based on the child's perception of their weight status, those who perceived themselves to be overweight were about three times more likely (AOR=2.91, 95% CI 1.95 to 4.34) to try to lose weight. Parental perception of weight status, however, did not have a significant impact on children attempting to lose weight. Children's (AOR=1.56, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.15) and parent's desire (AOR=1.79, 95% CI 1.25 to 2.58) for the child to be thinner also increased the likelihood of attempting to lose weight. Based on a simpler model (model 2) the odds of attempting to lose weight was significantly higher among girls (AOR = 1.37, CI 1.11 to 1.70) compared to boys. Otherwise, the findings were similar to model 1.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic and anthropometric associations of weight loss behaviour

| Attempted weight loss | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value* | Adjusted OR† model 1 (95% CI) | p Value‡ | Adjusted OR§ model 2 (95% CI) | p Value‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Girls | 387 (39%) | 616 (61%) | 1.41 (1.16 to 1.72) | <0.001 | 1.16 (0.89 to 1.51) | 0.27 | 1.37 (1.11 to 1.70) | 0.01 |

| Boys | 268 (31%) | 603 (69%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Age category (years) | ||||||||

| ≤10 | 245 (34%) | 469 (66%) | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.17) | 0.65 | 1.04 (0.79 to 1.36) | 0.76 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.28) | 0.79 |

| >10 | 410 (35%) | 750 (65%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Location | ||||||||

| City | 408 (33%) | 812 (67%) | 0.83 (0.68 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.36) | 0.81 | ||

| Non-city | 247 (38%) | 407 (62%) | 1 | 1 | – | – | ||

| Education of mother (standard) | ||||||||

| Up to 7th | 146 (34%) | 278 (66%) | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.22) | 0.69 | 0.81 (0.58 to 1.14) | 0.22 | – | – |

| >7th | 400 (36%) | 727 (65%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Education of father (standard) | ||||||||

| Up to 7th | 161 (39%) | 256 (61%) | 1.21 (0.95 to 1.53) | 0.10 | 1.24 (0.87 to 1.78) | 0.22 | – | – |

| >7th | 437 (34%) | 838 (66%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medium of instruction | ||||||||

| Kannada | 198 (39%) | 308 (61%) | 1.28 (1.03 to 1.59) | 0.02 | 1.57 (1.11 to 2.25) | 0.01 | 1.52 (1.20 to 1.92) | <0.001 |

| English1 | 457 (33%) | 911 (67%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Actual weight status | ||||||||

| Underweight | 98 (22%) | 352 (78%) | 0.52 (0.40 to 0.67) | <0.001 | 0.71 (0.51 to 0.98) | 0.04 | 0.66 (0.50 to 0.86) | 0.002 |

| Overweight | 125 (73%) | 47 (27%) | 4.96 (3.43 to 7.20) | <0.001 | 4.38 (2.64 to 7.28) | <0.001 | 3.86 (2.63 to 5.64) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 412 (35%) | 769 (65%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Child's perception of body image | ||||||||

| Too/a little thin | 133 (23%) | 457 (77%) | 0.61 (0.48 to 0.77) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.93) | 0.01 | 0.64 (0.49 to 0.82) | <0.001 |

| A little /too fat | 195 (68%) | 91 (32%) | 4.48 (3.35 to 6.00 | <0.001 | 2.91 (1.95 to 4.34) | <0.001 | 3.48 (2.57 to 4.69) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 318 (32%) | 665 (68%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Child's desire to be | ||||||||

| A lot /slightly fatter | 114 (25%) | 347 (75%) | 0.76 (0.58 to 0.98) | 0.03 | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.20) | 0.35 | ||

| Slightly/much thinner | 260 (52%) | 237 (48%) | 2.53 (2.00 to 3.19) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.14 to 2.15) | 0.006 | – | – |

| Same as at present | 272 (30%) | 627 (70%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Parent's perception of child's body image | ||||||||

| Too/a little thin | 66 (22%) | 241 (79%) | 0.52 (0.38 to 0.71) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.12) | 0.15 | – | – |

| A little /too fat | 95 (54%) | 82 (46%) | 2.20 (1.58 to 3.08) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.51 to 1.37) | 0.51 | ||

| Normal | 364 (35%) | 690 (66%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Parent's desire for child to be | ||||||||

| A lot /slightly fatter | 87 (21%) | 331 (79%) | 0.54 (0.41 to 0.72) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.52 to 1.07) | 0.11 | – | – |

| Slightly /much thinner | 170 (56%) | 134 (44%) | 2.61 (1.98 to 3.46) | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.25 to 2.58) | 0.002 | ||

| Same as at present | 263 (33%) | 542 (67%) | 1 | 1 | ||||

Results are reported in terms of number (%).

*p value for unadjusted OR obtained using either Fisher's exact test or χ2 test.

†Adjusted for actual body mass index status, child's and parents perception of body weight and sociodemographic factors.

‡Obtained by fitting binary logistic regression model. Model 1: adjusted for sociodemographic variables and actual and perceived weight.

§Obtained by fitting binary logistic regression model. Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, medium of instruction, actual weight status and the child's perception of body weight.

A stratified analysis based on age and gender (see online supplementary table S2) was also performed. While the groups were largely similar in terms of attempting to lose weight, significant differences were observed only among those children who were actually underweight as well as those who perceived themselves to be underweight. In these children, the prevalence of attempting to lose weight was significantly higher in older boys compared to that in older girls. Similarly, there was a significantly higher prevalence of younger girls attempting to lose weight compared to older girls, but not between the younger boys and the older boys.

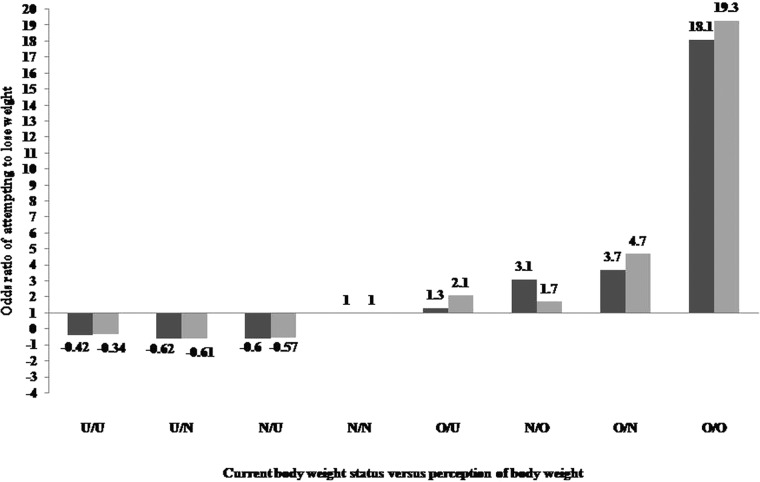

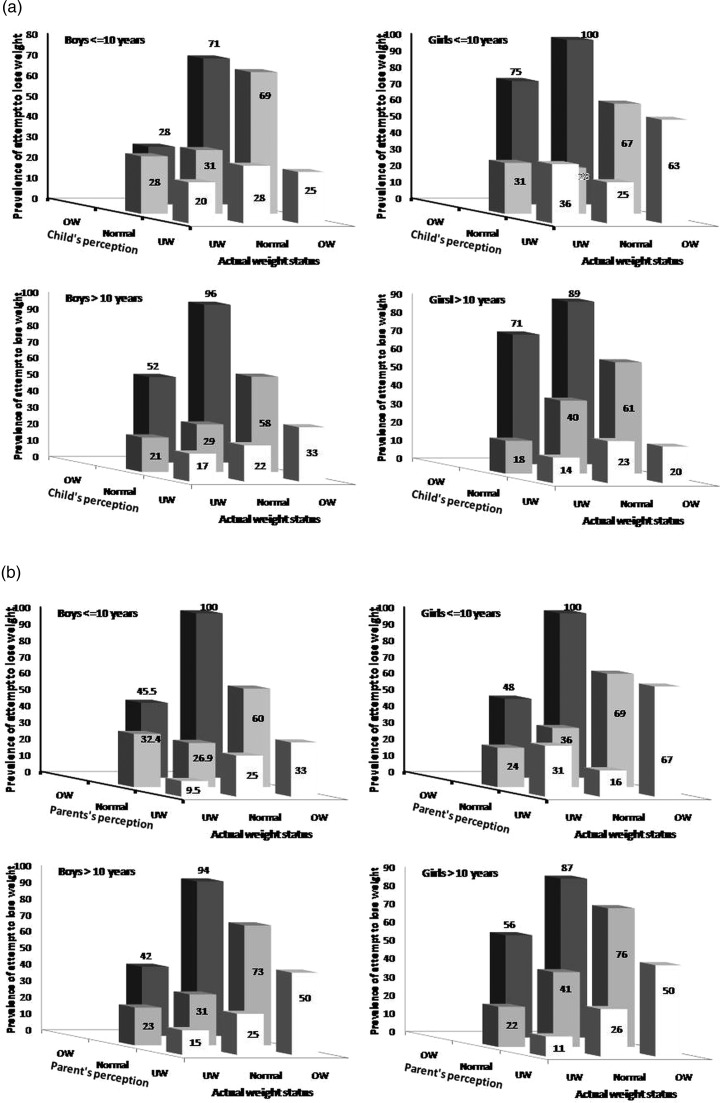

Figure 1 represents the odds of a child attempting to lose weight based on the child's actual weight status in combination with the child's/parent's perception of weight status. After adjusting for age, gender and medium of instruction, the odds of attempting to lose weight (figure 1, Supplementary table S3) increased from 3.1 (95% CI 2.2 to 4.4) for a normal weight child who perceive themselves to be overweight/obese, 3.7 (95% CI 2.2 to 6.2) for an overweight child who perceive themselves to be normal to 18.1 (95% CI 8.8 to 36.9) for an overweight child who perceive themselves to be overweight. A similar trend was observed when parental perceptions were replaced with child's perception (figure 1) with odds of attempting to lose weight increasing from 1.7 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.7) for normal weight child perceived by a parent to be overweight, 4.7 (95% CI 2.7 to 8) for an overweight child perceived by a parent to be normal to 19.3 (95% CI 6.8 to 54.8) for an overweight child perceived to be overweight by a parent. None of the underweight children were perceived by themselves or by their parents to be overweight. Among children who were underweight but perceived either by the child or the parent to be underweight or normal, the odds of attempting to lose weight was reduced by approximately 60–40%, respectively in relation to children of normal weight status perceived to be normal by both children and parents. The same analyses were performed using prevalence of attempting to lose weight based on actual weight status, child's perception and parent's perception of child's weight status stratified by age and gender (figure 2A,B).

Figure 1.

OR of having tried to lose body weight in children classified by current weight status and perception of body weight. ■ Comparison of child's actual weight status with child's perception of weight status.  Comparison of child's actual weight status with parental perception of weight status. U/U, underweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being underweight; U/N, underweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being normal; N/U, normal by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be underweight; N/N, normal by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being normal; N/O, normal by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being overweight; O/N, overweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being normal; O/O, overweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being overweight; O/U, overweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being underweight.

Comparison of child's actual weight status with parental perception of weight status. U/U, underweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being underweight; U/N, underweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being normal; N/U, normal by actual measurements/perceived by child/parent to be underweight; N/N, normal by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being normal; N/O, normal by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being overweight; O/N, overweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being normal; O/O, overweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being overweight; O/U, overweight by actual measurements/child's or parent's perception of being underweight.

Figure 2.

(A and B) Prevalence of attempting to lose weight by gender and age category based on actual weight status and children and parent's perception of child's body weight. UW, underweight; OW, overweight.

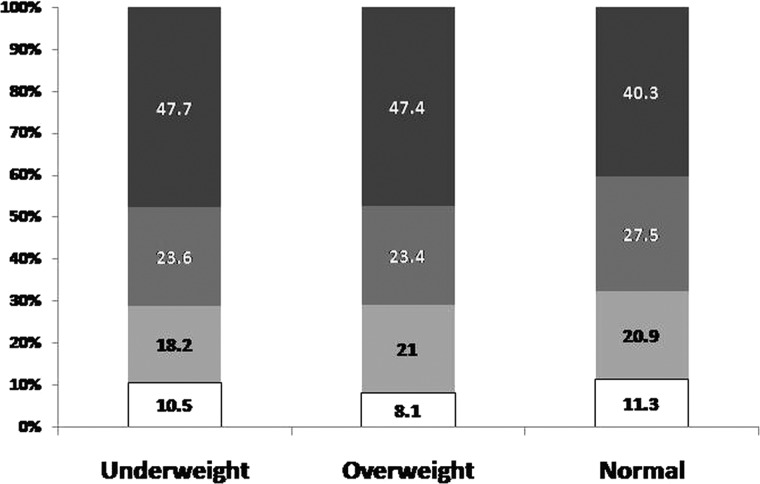

The most commonly adopted practice to lose weight regardless of whether children were underweight, overweight or normal was exercise (∼46%), followed by reducing the quantity of food intake, ceasing to eat certain kinds of foods and skipping meals (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Actual weight status and weight loss practices of children. ■ Exercise  Reduced quantity of food eaten;

Reduced quantity of food eaten;  Stopped eating certain kinds of foods □ Skipping meals.

Stopped eating certain kinds of foods □ Skipping meals.

Discussion

In concurrence with the findings of our study, misperception of weight status among children has been reported in other studies conducted in the USA, with perceptions differing between various ethnic groups. Among African-American adolescents, one-third perceived their weight status inaccurately.7 Racial or ethnic differences in weight perception have been reported,5 7 8 wherein Caucasians were found to be more likely than African-Americans to perceive themselves as overweight.5 7 9 However, this has not been a universal finding, as for instance in multiethnic adolescents in the UK.14 Perceptions, however, were also associated with their decision to attempt weight loss, notwithstanding their current weight status.

In general, children who were actually overweight as well as those who were perceived by themselves or by their parents to be overweight were likely to try to lose weight. This finding is similar to studies conducted in other countries.7 8 22 Unless individuals or their families perceive their weight status correctly, their acceptance of programmes designed to encourage healthy weight may be low.17

The child's or the parent's desire for the child to be thinner was also associated with their decision to attempt to lose weight. This desire was the highest among those who perceived themselves to be overweight, although about one-third of those who perceived themselves to be of normal weight and about one-fifth of those who perceived themselves to be underweight also attempted to lose weight. In contrast, among children who were underweight and those of normal weight, 32% and 23% desired to gain weight, respectively. This clearly indicates that in a country where both underweight and overweight coexist, care must be taken in developing programmes at a community level such that those who require to put on weight and those who need to lose weight are considered, as for example, in the school feeding programmes.

The fact that there were reported weight loss attempts even in the underweight group suggests that factors other than weight status and weight perception are operative. This is corroborated by the higher odds of children from Kannada medium schools who belong to a relatively lower SES compared to children from English medium schools (higher SES) trying to lose weight. Thus sociocultural factors may be associated with their decision to lose weight. This could be linked to the continuous exposure to images and unrealistic body shapes that encourage weight loss regardless of body weight.8 These factors must be further explored so that suitable programmes that encourage overweight children but not underweight or normal children to lose weight could be planned.

Children included in our sample were as young as 8 years of age. However, body dissatisfaction with increasing weight status was established even by the age of 5 in both boys and girls of South Asian origin in UK.3 Irrespective of whether they were below or above 10 years of age or whether they were boys or girls, children attempted to lose weight. In our study sample, there were no gender differences in weight loss attempts. This is contrary to the findings elsewhere, as for instance, the NHANES study16 indicated that girls were about 2.5 times more likely to attempt to lose weight. The absence of gender differences in our study may, in part, be because of the relatively low prevalence of overweight or obesity.

It is encouraging that 46% of children indicated exercise as their preferred choice of weight loss. Differences in the methods used to lose weight between overweight, normal and underweight children were not apparent unlike other studies where unhealthier weight loss methods like skipping meals have been reported more in overweight or obese children compared to normal weight children.23 However, an effect of social desirability cannot be discounted, given that exercise as a healthy lifestyle choice promoted early in the school curriculum.

Body image must be taken into account when designing programmes to improve both body image and reduce unhealthy behaviours like unhealthy eating and reduced or excessive exercise.1 Since public health programmes are generally targeted towards all, a general programme that caters to all children irrespective of their weight status is required.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to report perceptions of body weight in India in relation to weight loss attempts. A major strength of this study is that measured heights and weights rather than self-reported were used for assessment and the study sample encompassed children of diverse socioeconomic strata, from rural and urban areas and of a large body weight range. However, with the cross-sectional study design used in this study, the changes in perception as the children grow cannot be accounted for. Longitudinal evaluation of these children will allow us to establish causal links between weight perception and weight loss behaviours. Both the facts that the study was cross-sectional in nature, as well as the design of the questionnaire were limitations as information regarding the frequency, duration and intensity of weight loss efforts or time-sequence of events, that is, the time (recent/current or past) at which such behaviours occurred could not be obtained. Data on the reliability and validity of the questionnaire are not available for this population. With the question asked on attempt to lose weight being dichotomous, there is a possibility that a child who has currently normal weight may report weight loss behaviours because they were overweight in the past. The small numbers of children in each category in the analysis stratified by actual and perceived weight status necessitates further exploration with larger numbers of children in each category. A further limitation is that we have not collected data on attempt to gain weight.

Overall, perception of weight status was associated with the decision of children to lose weight. This needs to be further explored as a longitudinal study to establish causal links. However, regardless of weight status, many children did resort to weight loss. Public health campaigns should emphasise healthy weight management rather than weight loss.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Roopashree who helped in acquisition and entry of part of the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP, SS and MV were responsible for the concept and design of the study. SS drafted the manuscript. MP acquired the data. SRS (Sumithra Selvam) performed the statistical analysis and interpreted the data. MV conceived the study and interpreted the data. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SS is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Ethical Review Board, St. John’s Medical College and Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Raw data are available from the statistician, Sumithra Selvam on request at sumithrars@sjri.res.in.

References

- 1.Grogan S. Body image and health: contemporary perspectives. J Health Psychol 2006;11:523–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cortese S, Falissard B, Pigaiani Y, et al. The relationship between body mass index and body size dissatisfaction in young adolescents: spline function analysis. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:1098–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pallan MJ, Hiam LC, Duda JL, et al. Body image, body dissatisfaction and weight status in South Asian children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain V, Singhal A. Catch up growth in low birth weight infants: striking a healthy balance. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2012;13:141–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin MA, May AL, Frisco ML. Equal weights but different weight perceptions among US adolescents. J Health Psychol 2010;15:493–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swami V, Frederick DA, Aavik T, et al. The attractive female body weight and female body dissatisfaction in 26 countries across 10 world regions: results of the international body project I. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2010;36:309–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Liang H, Chen X. Measured body mass index, body weight perception, dissatisfaction and control practices in urban, low-income African American adolescents. BMC Public Health 2009;9:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan JS, Duncan EK, Schofield G. Associations between weight perceptions, weight control and body fatness in a multiethnic sample of adolescent girls. Public Health Nutr 2010;14:93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neff LJ, Sargent RG, McKeown RE, et al. Black-white differences in body size perceptions and weight management practices among adolescent females. J Adolesc Health 1997;20:459–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viner RM, Haines MM, Taylor SJ, et al. Body mass, weight control behaviours, weight perception and emotional well being in a multiethnic sample of early adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1514–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceballos N, Czyzewska M. Body image in Hispanic/Latino vs. European American adolescents: implications for treatment and prevention of obesity in underserved populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21:823–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayala GX, Mickens L, Galindo P, et al. Acculturation and body image perception among Latino youth. Ethn Health 2007;12:21–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cachelin FM, Rebeck RM, Chung GH, et al. Does ethnicity influence body-size preference? A comparison of body image and body size. Obes Res 2002;10:158–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haff HR. Racial/ethnic differences in weight perceptions and weight control behaviors among adolescent females. Youth Soc 2009;41:278–301 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ojala K, Vereecken C, Valimaa R, et al. Attempts to lose weight among overweight and non-overweight adolescents: a cross-national survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan AF, Zhang G, Wang MQ, et al. Weight perception and weight control practice in a multiethnic sample of US adolescents. South Med J 2009;102:354–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards NM, Pettingell S, Borowsky IW. Where perception meets reality: self-perception of weight in overweight adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;125:e452–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauline M, Selvam S, Swaminathan S, et al. Body weight perception is associated with socio-economic status and current body weight in selected urban and rural South Indian school-going children. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:2348–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:660–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stunkard AJ, Sorensen T, Schulsinger F. Use of the Danish adoption register for the study of obesity and thinness. In: Kety SS RL, Sidman RL, Matthysse SW, eds. Genetics of neurological and psychiatric disorders. New York: Raven Press, 1983:115–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization Nutrition in adolescence. Issues and challenges for the health sector. Discussion paper Geneva: WHO, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alwan H, Viswanathan B, Paccaud F, et al. Is accurate perception of body image associated with appropriate weight-control behavior among adolescents of the seychelles. J Obes 2011;2011:817242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boutelle K, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, et al. Weight control behaviors among obese, overweight, and nonoverweight adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 2002;27:531–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.