Abstract

Objective

To determine the incidence and impact of recurrent workplace injury and disease over the period 1995–2008.

Design

Population-based cohort study using data from the state workers’ compensation system database.

Setting

State of Victoria, Australia.

Participants

A total of 448 868 workers with an accepted workers’ compensation claim between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2008 were included into this study. Of them, 135 349 had at least one subsequent claim accepted for a recurrent injury or disease during this period.

Main outcome measures

Incidence of initial and recurrent injury and disease claims and time lost from work for initial and recurrent injury and disease.

Results

Over the study period, 448 868 workers lodged 972 281 claims for discrete occurrences of work-related injury or disease. 53.4% of these claims were for recurrent injury or disease. On average, the rates of initial claims dropped by 5.6%, 95% CI (−5.8% to −5.7%) per annum, while the rates of recurrent injuries decreased by 4.1%, 95% CI (−4.2% to −0.4%). In total, workplace injury and disease resulted in 188 978 years of loss in full-time work, with 104 556 of them being for the recurrent injury.

Conclusions

Recurrent work-related injury and disease is associated with a substantial social and economic impact. There is an opportunity to reduce the social, health and economic burden of workplace injury by enacting secondary prevention programmes targeted at workers who have incurred an initial occupational injury or disease.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health, Statistics & Research Methods

Article summary.

Article focus

To determine the incidence and impact of recurrent workplace injury and disease in Victoria, Australia over the period 1995–2008.

Key messages

A recurrent workplace injury and disease is frequent and associated with a substantial work disability. We established that over the 14-year study period in the state of Victoria, Australia, more than 50% of claims were filed for a recurrent injury or disease. In addition, we found that the majority (104 556 years) of time lost from work was from the recurrent claims.

There is an opportunity to reduce the social, health and economic burdens of workplace injury by enacting secondary prevention programmes targeted at workers who have incurred an initial occupational injury or disease.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The principal strength is that this is the first study to summarise the overall impact of work disability and annual trends of subsequent work-related injury and disease, as most of the past studies treated claims as single and discrete events.

The main weakness of this study is that it is a Victoria only specific study, and the database does not cover the entire population; certain injuries maybe underreported, and therefore, results published here may be underrepresented, that is, workers may not claim for mental health-related issues, they possibly have claimed in other institutions in the past or they are self-covered.

Introduction

Work is now generally acknowledged as being good for health.1 There is a growing trend internationally to encourage early return-to-work after injury or illness as a means of facilitating recovery, well-being and social inclusion. Conversely, periods of unemployment can lead to poor health or exacerbate existing health issues.1 Disability arising from workplace injury and illness is also now the subject of substantial public policy and academic interest.2

Workers’ compensation claims data have been an important source of information to describe the incidence and impact of work-related injury and disease within and across jurisdictions internationally.3–5 Studies in this area reveal the substantial health and economic costs of workplace injury and illness.6 7 For example, the total cost of healthcare of officially recognised injured workers in Mexico in 2005 was US$753 420 222.8 Similarly, workers’ compensation insurance for US workers in 2007 cost US$85 billion.9 Over the past two decades, the concept of ‘work disability’, usually measured as the number of days lost from work, has emerged as a means of estimating the burden of workplace injury and disease.2

More recently, we and others have utilised workers’ compensation system data to focus on recurrent workplace injury or disease.10–12 These studies in discrete populations or over discrete time periods have demonstrated that injury and disease recurrences contribute substantially to the overall burden of workplace injury and disease. There are numerous examples of population-based estimates of the overall burden of workplace injury and disease, including detailed epidemiological analysis of time series.13–15 However, these studies do not differentiate between initial and recurrent episodes of injury or disease. Examining annual trends of the initial and recurrent occupational injury may provide us a better understanding of the relative effectiveness of primary and secondary prevention initiatives.16 17

The current study sought to determine the incidence and impact of a recurrent workplace injury and disease in the state of Victoria, Australia over a 14-year period using the data from the state workers’ compensation system. This study has two aims: (1) to describe the annual incidence of initial and recurrent workplace injury and disease, and (2) to summarise the disability associated with initial and recurrent workplace injury and disease.

Methods

Setting

Victoria is a state of approximately 5.5 million people with an approximate full-time working population of 2.4 million (year 2010 data obtained from http://www.abs.gov.au). The Victorian WorkCover Authority (VWA) is the state government occupational health and safety and workers’ compensation authority. To be eligible for workers’ compensation benefits, the worker must be able to demonstrate a causal link between the injury or disease and their work. Employers are responsible for income replacement for the first 10 days away from work, beyond which the VWA provides income replacement benefits. Reasonable healthcare and rehabilitation benefits are also provided by the VWA. In total, 85–90% of workers in the state have their workers’ compensation insurance provided by the VWA. Exceptions are federal government employees, sole traders and employees of some large self-insured employers.

Compensation database

A deidentified workers’ compensation administrative database for the period from 1986 was obtained from the VWA for the purpose of this study. The database contains information regarding the claimant, injury or disease and benefits paid in relation to the claim. Records include information on the claimant and the benefits paid. The Australian Standard Type of Occurrence Classification System (V.3)18 was used to code the nature/mechanism of affliction. Occupation data were coded using Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupation.19 The Australian New Zealand Standard Industry Classification (2006) was used to code industry data.20 A detailed description of the compensation database can be found elsewhere.11

Data analysis

All accepted workers’ compensation claims occurring between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2008 were included in this study. Descriptive statistics were used to provide an overview of initial (first claim of a worker) and recurrent claims by gender, age, nature of affliction (injury or disease) and type of benefits paid (income replacement and medical expenses). A recurrent claim in this study was defined as a second or any subsequent claim of a worker during the study period, and it could have occurred for the same as an initial or a completely different reason. Two outcomes were considered in this study: the rates of initial and recurrent injury and disease over the 14-year period; and the number of compensated days away from work (extracted from the database), which was used as the indicator of ‘work disability’.21

The incidence of initial and recurrent claims per annum was calculated as a rate per 1000 workers, for men and women. Denominator data were drawn from the Australian Bureau of Statistics labour force survey for the state of Victoria (http://www.abs.gov.au). A fully adjusted for age and gender Poisson count regression model was used to determine annual changes in rates between initial and recurrent injury and disease. SPSS V.20.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

Initial and recurrent workplace injury and disease

Over the study period of 14 years, a total of 448 868 workers lodged compensation claims for 972 281 discrete occurrences of work-related injury or disease (table 1). Recurrent injury and disease accounted for 53.4% of all claims. These were attributable to only 26.2% of all claimants.

Table 1.

Profile of initial and recurrent workers’ compensation claims by category in Victoria, 1995–2008

| Category | Initial claims |

Recurrent claims |

Total claims |

p Value |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Rate, 95% CI | Row % | Col % | N | Rate, 95% CI | Row % | Col % | N | Rate, 95% CI | Row % | Col % | Row | Col | |

| Total claims | 448868 | 19.1 (15.2 to 20.1) | 46.2 | – | 523413 | 22.3 (21.2 to 23.4) | 53.4 | – | 972281 | 41.5 (39.4 to 43.5) | 100 | – | 0.000 | – |

| Total claimants | 448868 | 19.1 (15.2 to 20.1) | 76.8 | – | 135349 | 5.8 (5.5 to 6.1) | 26.2 | – | 584217 | 24.9 (23.7 to 26.2) | 100 | – | 0.000 | – |

| Claims per claimant | 1 | – | – | – | 3.86 | – | – | – | 1.66 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gender* | ||||||||||||||

| Males | 274915 | 17.7 (16.8 to 18.5) | 75.1 | 61.2 | 91072 | 5.9 (5.6 to 6.1) | 24.9 | 67.3 | 365987 | 23.5 (22.3 to 24.7) | 100 | 62.6 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Females | 163059 | 20.7 (19.6 to 21.7) | 79.8 | 36.3 | 41111 | 5.2 (5.0 to 5.5) | 20.2 | 30.4 | 204170 | 25.9 (24.6 to 27.2) | 100 | 34.9 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Missing | 10894 | 0.46 (0.44 to 0.49) | 77.5 | 2.4 | 3166 | 0.13 (0.13 to 0.14) | 22.5 | 2.3 | 14060 | 0.59 (0.57 to 0.63) | 100 | 2.5 | 0.003 | NS |

| Age category* | ||||||||||||||

| 15–19 | 33393 | 54.3 (51.6 to 57.0) | 76.0 | 7.4 | 10571 | 17.2 (16.3 to 18.0) | 24.0 | 7.8 | 43964 | 71.5 (67.9 to 75.1) | 100 | 7.5 | 0.000 | NS |

| 20–24 | 68421 | 27.6 (26.2 to 29.0) | 76.6 | 15.2 | 20858 | 8.4 (8.0 to 8.8) | 23.4 | 15.4 | 89279 | 36.0 (34.2 to 37.8) | 100 | 15.3 | 0.000 | NS |

| 25–34 | 117817 | 18.2 (17.3 to 19.1) | 76.5 | 26.2 | 36132 | 5.6 (5.3 to 5.9) | 23.5 | 26.7 | 153949 | 23.8 (22.6 to 25.0) | 100 | 26.4 | 0.000 | NS |

| 35–44 | 103799 | 17.2 (16.4 to 18.1) | 75.3 | 23.1 | 33963 | 5.6 (5.4 to 5.9) | 24.7 | 25.1 | 137762 | 22.9 (21.7 to 24.0) | 100 | 23.6 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 45–54 | 87619 | 16.5 (15.7 to 17.3) | 77.1 | 19.5 | 26057 | 4.9 (4.7 to 5.2) | 22.9 | 19.3 | 113676 | 21.4 (20.3 to 22.5) | 100 | 19.5 | 0.000 | NS |

| 55–59 | 24086 | 15.4 (14.6 to 16.2) | 81.0 | 5.4 | 5667 | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 19.0 | 4.2 | 29753 | 19.0 (18.1 to 20.0) | 100 | 5.1 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 60–64 | 10828 | 14.8 (14.1 to 15.6) | 85.6 | 2.4 | 1817 | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.6) | 14.4 | 1.3 | 12645 | 17.3 (16.5 to 18.2) | 100 | 2.2 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| 65+ | 2905 | 10.4 (9.9 to 11.0) | 91.1 | 0.6 | 284 | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 8.9 | 0.2 | 3189 | 11.5 (10.9 to 12.0) | 100 | 0.5 | 0.000 | NS |

| Nature of affliction | ||||||||||||||

| Injury | 340203 | 14.5 (13.8 to 15.2) | 47.4 | 75.8 | 376033 | 16.0 (15.2 to 16.8) | 52.6 | 71.8 | 716236 | 30.5 (29.0 to 32.1) | 100 | 73.6 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Disease | 108665 | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.9) | 42.4 | 24.2 | 147380 | 6.3 (6.0 to 6.6) | 57.6 | 28.2 | 256045 | 10.9 (10.4 to 11.5) | 100 | 26.4 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Compensation benefits paid | ||||||||||||||

| Income replacement ± medical expenses† | 257082 | 11.0 (10.4 to 11.5) | 46.8 | 57.3 | 292340 | 12.5 (11.8 to 13.1) | 53.2 | 55.8 | 549422 | 23.4 (22.3 to 24.6) | 100 | 56.5 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Medical expenses only | 191786 | 8.2 (7.8 to 8.6) | 45.4 | 42.7 | 231073 | 9.9 (9.4 to 10.3) | 54.6 | 44.2 | 422859 | 18.0 (17.1 to 18.9) | 100 | 43.5 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

*The rates are presented for claimants, not claims.

†‘Income replacement ± medical expenses’ group represents these claimants, who had time off work and/or required compensation for medical expenses.

Men were more likely to have a recurrent injury or disease than women. A majority of claims were for occupational injuries. The vast majority of claimants were 25–44years old; however, the incidence rates of the initial and recurrent injuries or diseases were highest in the youngest workers, 15–19 years of age.

Occupational diseases were more likely to result in subsequent workers’ compensation claims (24.2% vs 28.2%). The majority of claims were lodged for income replacement and/or medical expenses.

Incidence of initial and recurrent workplace injury and disease

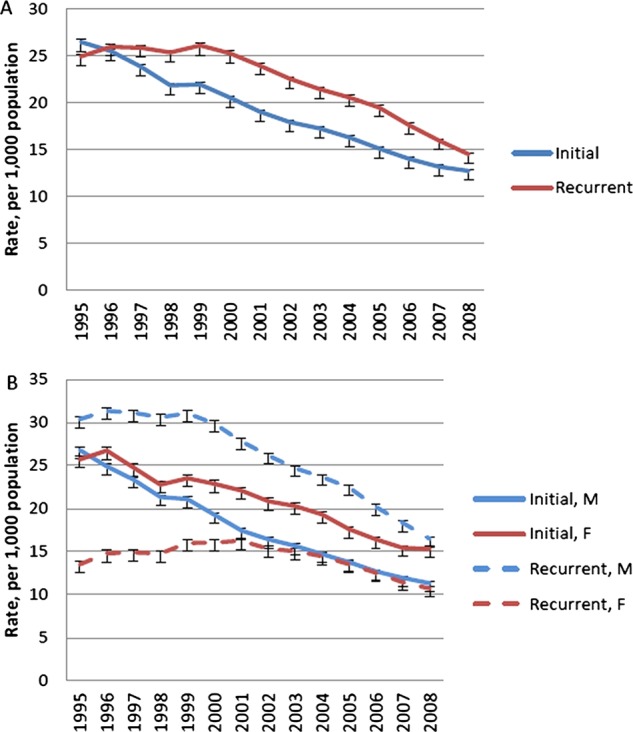

The rates of initial and recurrent workplace injury and disease per 1000 working population are displayed in Figure 1. Figure 1A illustrates the incidence per annum of initial and recurrent claims per 1000 working population. The rates of initial injury reduced from 26.4/1000 in 1995 to 12.7/1000 in 2008 (or by 6.1% per annum, p<0.0001, 95% CIs −6.3 to −5.8). The rates of recurrent injury decreased from 24.9/1000 in 1995 to 14.5/1000 in 2008 (or by 3.5% per annum, p<0.0001, 95% CIs −3.7 to −3).

Figure 1.

Incidence of initial (A) and recurrent (B) workplace injury and disease per 1000 workers in Victoria, 1995–2008.

Figure 1B illustrates the annual incidence rates per 1000 working population of initial and recurrent injury and disease, in men and women separately. The rates of initial injury and disease in men decreased by 6.7% (p<0.0001, 95% CIs −7.4 to −5.9) than in women. However, the rates of recurrent injury and disease in men every year increased by 3%, (p<0.0001, 95% CIs 2.4 to 3.7) when compared with women. The incidence rates of recurrent injuries and diseases were higher than in the initial claims by 4.5% (p<0.0001, 95% CIs 3.9% to 5.3%) in men, and by 7.4% (p<0.0001, 95% CIs 5.0 to 9.8) in women.

Work disability

Table 2 summarises work disability associated with the initial and recurrent injury and disease. In total, over the study period of 14 years, workplace injury and disease resulted in 188 978 years of full-time work loss. More than half (55.3%) of this burden was caused by recurrent injury and disease.

Table 2.

Total work disability arising from initial and recurrent workers’ compensation claims in Victoria, 1995–2008

| Category | Initial claims |

Recurrent claims |

Total claims |

p Value |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Row % | Col % | N | Row % | Col % | N | Row % | Col % | Row | Col | |

| Work-loss, years | |||||||||||

| All time-loss claims | 84422 | 44.7 | – | 104556 | 55.3 | – | 188978 | 100 | – | 0.000 | – |

| Males | 45570 | 38.7 | 53.4 | 72211 | 61.3 | 69.1 | 117781 | 100 | 62.3 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Females | 38130 | 54.8 | 45.2 | 31404 | 45.2 | 30.1 | 69534 | 100 | 36.8 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Injury | 53713 | 44.8 | 63.6 | 66026 | 55.2 | 63.1 | 119739 | 100 | 63.4 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Disease | 30709 | 44.4 | 36.4 | 38530 | 55.6 | 36.9 | 69239 | 100 | 36.6 | 0.000 | NS |

| Age category | |||||||||||

| 15–19 | 2170 | 84.6 | 2.6 | 396 | 15.4 | 0.4 | 2566 | 100 | 1.4 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| 20–24 | 6050 | 66.8 | 7.2 | 3010 | 33.2 | 2.9 | 9060 | 100 | 4.8 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 25–34 | 17350 | 50.5 | 20.6 | 16980 | 49.5 | 16.2 | 34330 | 100 | 18.2 | NS | 0.000 |

| 35–44 | 23606 | 44.0 | 28.0 | 30012 | 56.0 | 28.7 | 53618 | 100 | 28.4 | 0.000 | NS |

| 45–54 | 24943 | 40.6 | 29.5 | 36493 | 59.4 | 34.9 | 61436 | 100 | 32.5 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 55–59 | 7426 | 37.0 | 8.8 | 12650 | 63.0 | 12.1 | 20076 | 100 | 10.6 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 60–64 | 2468 | 35.8 | 2.9 | 4418 | 64.2 | 4.2 | 6886 | 100 | 3.6 | 0.000 | 0.006 |

| 65+ | 408 | 40.6 | 2.6 | 597 | 59.4 | 0.6 | 1005 | 100 | 0.5 | 0.000 | 0.008 |

Men incurred 45 570 (38.7%) years of full-time work loss due to the initial injury, and 72 211 (61.3%) years—due to the recurrent injury and disease. Women incurred 38 130 (54.8%) years of full-time work loss during their initial claims. This amount of time decreased to 31 404 (45.2%) years in recurrent injury and disease. Occupational injuries accounted for 53 713 (44.8%) years of work disability in all initial claims and 66 026 (55.2%) years in recurrent injury. Work disability incurred for a recurrent disease, relatively to the initial claims, was similar: 38 530 (55.6%) and 30 709 (44.4%) years, respectively, of full time work loss. Workers in the 45–54 years of age category incurred the highest amount of work loss–24 973 years in initial injuries and diseases and 36 493 years in recurrent injuries and diseases.

The average duration of time lost due to workplace injury and disease (table 3) was 85.6 (257.1) days; however, it was higher for recurrent claims (93.4(276.5) days). The average duration of time lost varied greatly across the age categories of injured workers, and it increased with workers’ age.

Table 3.

Average and median work disability arising from initial and recurrent workers compensation claims in Victoria, 1995–2008

| Category | Initial claims |

Recurrent claims |

Total claims |

p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), days | Median (IQR), days | Mean (SD), days | Median (IQR), days | Mean (SD), days | Median (IQR), days | Row | |

| All time-loss claims | 85.6 (257.1) | 10 (10–38) | 93.4 (276.5) | 10 (10–39) | 89.8 (267.6) | 10 (10–39) | 0.000 |

| Males | 76.2 (241.3) | 10 (10–34) | 86.4 (267.2) | 10 (10–34) | 82.2 (256.7) | 10 (10–34) | 0.000 |

| Females | 102.9 (284.2) | 10 (10–50) | 118.5 (309.6) | 10 (10–65) | 109.4 (295.1) | 10 (10–56) | 0.000 |

| Injury | 75.1 (244.0) | 10 (10–30) | 86.1 (275.9) | 10 (10–30) | 80.7 (261.2) | 10 (10–30) | 0.000 |

| Disease | 113.9 (286.5) | 14 9 (10–71) | 109.3 (277.1) | 11 (10–65) | 111.3 (281.3) | 13 (10–67) | 0.000 |

| Age category | |||||||

| 15–19 | 29.5 (91.6) | 10 (10–16) | 26.7 (91.6) | 10 (10–10) | 29.0 (91.6) | 10 (10–15) | NS |

| 20–24 | 40.1 (123.7) | 10 (10–21) | 40.3 (135.7) | 10 (10–15) | 40.2 (127.8) | 10 (10–20) | NS |

| 25–34 | 68.5 (207.6) | 10 (10–31) | 65.5 (205.9) | 10 (10–26) | 66.9 (206.7) | 10 (10–29) | NS |

| 35–44 | 102.7 (286.6) | 10 (10–48) | 92.6 (275.6) | 10 (10–39) | 96.8 (280.3) | 10 (10–42) | 0.000 |

| 45–54 | 127.2 (349.8) | 11 (10–63) | 120.7 (340.6) | 10 (10–55) | 123.2 (344.3) | 10 (10–58) | 0.034 |

| 55–59 | 139.3 (336.9) | 15 (10–70) | 136.1 (337.2) | 12 (10–67) | 137.5 (337.1) | 13 (10–68) | NS |

| 60–64 | 106.9 (213.5) | 16 (10–72) | 101.6 (204.7) | 15 (10–72) | 103.5 (207.8) | 16 (10–72) | NS |

| 65+ | 80.6 (122.5) | 25 (10–85.75) | 76.8 (127.4) | 20 (10–70) | 78.3 (125.5) | 22 (10–77) | NS |

Discussion

Principal findings

This large-scale administrative data study, designed to provide a population-based overview of workers’ compensation claims, showed that a recurrent workplace injury and disease is frequent and associated with a substantial work disability. We established that over the 14-year-study period, 448 868 workers in the state of Victoria, Australia lodged 972 281 compensation claims; 53.4% of them were filed for a recurrent injury or disease (table 1). The incidence rates were highest in the youngest workers, possibly due to the denominator accounting for the full-time employees. Younger workers usually choose temporary or part-time employment; they are less experienced and are less aware of hazardous working conditions; therefore, they are at a higher risk of occupational injuries.22 Different patterns for men and women for recurrent injuries and diseases (Figure 1B) are associated with the lower number of women returning to work after the initial injury, which might occur due to the mental stress, depressive symptoms and vulnerability at work.23 In agreement with the previously reported findings, we observed that rates of work-related injury and disease were declining, which is probably associated with legislative changes, unemployment rates or seasonal affects and, most importantly, with better strategies and increased effectiveness of injury prevention.14 15 24 25

In both initial and recurrent injuries/diseases, the work disability increased with claimants’ age, which possibly was related to claimants’ comorbidities, changes in physical and mental capacity or attitudes to return to work.26 27 In addition, we found that the majority (104 556 years) of time lost from work was from the recurrent claims (table 2). This is equivalent to ∼10.4 days for each working person in Victoria. Despite that, sickness absence as a proportion of working time is decreasing; these figures are still substantial and represent a significant cost to the economy.28

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The first strength of this study is the large and exclusive compensation research data source, containing detailed and objective information on workers, their injuries and diseases. The entries of the dataset are unique and no duplicate information is recorded. The second and principal strength is that, to our knowledge, this is the first study to summarise the overall impact of work disability and annual trends of subsequent work-related injury and disease, as most of the past studies treated claims as single and discrete events.14 15 29–31 The scientific papers published earlier focused on the first return-to-work and time lost on temporary disability benefits as outcomes of the workplace-related injury. These studies concluded that work-related injury and illness affects not only injured workers, but also employers, society and government.7 29 32–37 Alternatively, only a few recent studies emphasised the burden of subsequent workers’ compensation claims; however, these studies analysed only the initial and second claims, but did not consider any further work-related injuries or illnesses.10–12 38 Lack of understanding of the overall impact of a recurrent workplace injury and disease instigates a significant dilemma associated with the employment rates and earnings of injured workers, adverse effects on productivity and costs, including those associated with compensation.9 33 39

The first weakness of this study is that it is a Victoria only specific study, and the database does not cover the entire population; certain injuries may be underreported, and therefore, the results published here may be underrepresented, that is, workers may not claim for mental health-related issues, they possibly have claimed in other institutions in the past or they are self-covered.40 41 Second, we do not have information on claimants’ return to work as these dates are not recorded consistently by the compensation authority, particularly for periods before the year 2004/2005. The reliability of these data is improving as the VWA gains more experience with collecting return to work outcomes. It is difficult to estimate the magnitude of these impacts without undertaking a comprehensive data linkage between jurisdictional workers’ compensation and health datasets.11 42 Third, administrative data collection errors might have also occurred, which could have affected the nature and dates of subsequent injuries or diseases. In addition, legislative changes and organisational policies might have affected the claim rates reported here.43 It is also important to acknowledge that the present study does not report trends in claim costs or cost effectiveness analysis over the years; however, it is already known that repeat workers’ compensation claims are associated with increased costs of medical and like services and weekly compensation paid.11

Conclusions and policy implications

The most effective strategy for preventing work-related disability is a primary prevention approach, that is, preventing the initial work-related injury and disease.44 The findings of the current study highlight a steady decline in the number of initial work-related injury and disease (Figure 1), indicating that primary injury prevention strategies at the workplace are becoming more and more efficient over the years.14 An accelerating reduction of recurrent injuries and diseases suggests that secondary prevention initiatives were possibly reviewed and addressed more carefully after 1999. Despite the current return-to-work efforts and decreasing rates of the initial and recurrent injury and disease, there is probably still more room for improvement. Current injury prevention policies and procedures need to be regularly revised, focusing on more efficient secondary prevention.45–47 The key to a successful secondary prevention is not only appropriately trained staff, but also clearly identified risk factors at the workplace and a combination of early predictors for poor long-term outcomes in workers.16 17 Both the injured worker and their employer are known to the compensation authorities, and therefore can be targeted by OH&S regulators and policy makers. It is essential to consider other factors such as precarious working conditions, worker's age, gender and comorbidities.48–50 The type of recurrent injury and disease is also known to the compensation authorities; therefore, if a subsequent claim was lodged along with the initial claim, or under completely different circumstances, alternative prevention measures should be considered.

Secondary prevention examples may include activities that promote lifestyle changes and aim at improving the overall health of injured workers, restructuring the current workplace where the injury occurs, providing suitably modified work for injured workers, recommending them to undergo regular exams and screening tests or surveillance systems.5 51 Return-to-work coordinators, clinicians and care management support also play an important role in workers’ return-to-work and reinjury prevention. Their efforts may need to be revisited with incentives provided so that reduced costs for workers’ compensation healthcare and increased safety practices are implemented.39 Education of workers in order to enable them to be more aware of hazards associated with their job may be an important step forward. Introducing work wellness and rehabilitation programmes, and providing counselling and job training for returning-to-work staff members may also assist in a further reduction of reinjury.2 39 51 52

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan Tinsley and Catherine Smith for their support during the development of this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors were responsible for the design of the study, evolved analysis plans, interpreted data and critically revised successive drafts of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research and the involvement of Dr Ruseckaite and Dr Collie in the study was provided by a research grant from WorkSafe Victoria.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee, Melbourne, Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Workers’ compensation data used in this study were collected by WorkSafe Victoria and held by ISCRR, who regularly responded to data requests from the public.

References

- 1.Wadell G, Burton A. Is work good for your health and well-being? London: TSO, Department for Work and Pensions, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pransky G, Loisel P, Anema J. Work disability prevention research: currrent and future prospects. J Occup Rehabil 2011;21:287–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anema J, Schellart A, Cassidy J, et al. Can cross country differences in return-to-work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? An explanatory analysis on dissability policies in a six country cohort study. J Occup Rehabil 2009;19:419–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campolieti M. Multiple state hazard models and workers’ compensation claims: an examination of workers compensation data from Ontario. Acc Anal Prev 2000;33:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcy P, Mayer T, Gatchel R. Recurrent or new injury outcomes after return to work in chronic disabling spinal disorders: tertiary prevention efficacy and functional restoration treatment. Spine 1996;21:952–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shuford H, Restrepo T, Beaven B, et al. Trends in components of medical spending within workers compensation: results from 37 states combined. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:232–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith P, Chen C, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Trends in the health care use in expenditures associated with no-lost-time claims in Ontario: 1991 to 2006. JOEM 2011;53:211–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlos-Rivera F, Aguilar-Madrid G, Gómez-Montenegro P, et al. Estimation of health-care costs for work-related injuries in the Mexican Institute of Social Security. Am J Ind Med 2009;52:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utterback D, Schnorr T, Silverstein B, et al. Occupational health and safety surveillance and research using workers’ compensation data. JOEM 2012;54:1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherry N, Sithole F, Beach J, et al. Second WCB claims: who is at risk? Can J Public Health 2010;101(Suppl 1):S53–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruseckaite R, Collie A. Repeat workers’ compensation claims: risk factors, costs and work disability. BMC Public Health 2011;11:492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bena A, Mamo C, Marinacci C, et al. Risk of repeat accidents by economic activity in Italy. Safety Sc 2006;44:297–312 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yassi A, Gilbert M, Cvitkobvich Y. Trends in injuries, illnesses, and policies in Canadian healthcare workplaces. Can J Public Health 2005;96:333–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslin F, Smith P, Moore I. Examining the decline in lost-time claim rates across age groups in Ontario between 1991 and 2007. Occup Environ Med 2011;68:813–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore I, Tompa E. Understanding changes over time in workers’ compensation claim rates using time series analytical techniques. Occup Environ Med 2011;68:837–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arocena P, Nunez P, Villanueva M. The impact of prevention measures and organizational factors on occupational injuries. Saf Sci 2008;46:1369–84 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzman J, Yassi A, Baril R, et al. Decreasing occupational injury and disability: the convergence of systems theory, knowledge transfer and action research. Work 2008;30:229–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Government Australialia Type of occurence classification system. 3rd edn (revision 1). Canberra: Australian Safety and Compensation Council, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 19.ANZSCO—Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations In: Statistics ABo ed. Canberra, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Australian and New Zealand Standad Industrial Classification (ANZSIC) In: Zealand. ABoSaSN ed. Canberra, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berecki-Gisolf J, Clay F, Collie A, et al. Predictors of sustained return to work after work-related injury or disease:insights from workers’ compensation claims records. J Occup Rehabil 2011;22:283–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virtanen M, Kivimaki M, Joensuu M, et al. Temporary employment and health: review. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:610–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koopmans P, Bultmann U, Roelen C, et al. Recurrence of sickness abscence due to common mental disorders. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2011;84:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gatty C, Turner M, Buitendorp D, et al. The effectiveness of back pain and injury prevention programs in the workplace. Work 2003;20:257–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foley M, Fan Z, Rauser E, et al. The impact of regulatory enforcement and consultation visits on workers’ compensation claims incidence rates and costs, 1999–2008. Am J Ind Med 2012;55:976–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ilmarinen J. Aging workers. Occup Environ Med 2001;58:546–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny G, Yardley J, Martineau L, et al. Physical work capacity in older adults: implications for the aging workers. Am J Ind Med 2008;51:610–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London: Crown Copyright, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berecki-Gisolf J, Clay F, Collie A, et al. The impact of ageing on work disability and return to work: insights from workers’ compensation claim records. JOEM 2012;54:318–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson D, Fry T. Factors affecting return to work after injury: a study for the Victorian WorkCover authority Melbourne Institute Working Paper No. 28/02 2002.

- 31.Smith P, Hogg-Johnson S, Mustard C, et al. Comparing the risk factors associated with seriuos versus and less seriuos work-related injuries in Ontario between 1991 and 2006. Am J Ind Med 2012;55:84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boden L, Biddle E, Spieler E. Social and economic impacts of workplace illness and injury: current and future directions for research. Am J Ind Med 2001;40:398–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boden L, Galizz M. Economic consequences of workplace injuries and illnesses: lost earnings and benefit adequacy. Am J Ind Med 1999;36:487–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.John F, Kerr M, Brooker A, et al. Disability resulting from occupational low back pain: part II: what do we know about secondary prevention? A review of the scientific evidence on prevention after disability begins. Spine 1996;21:2918–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leigh J, Markowitz S, Fahs M, et al. Occupational illness and injury in the United States: estimates of costs, morbidity, and mortality. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1557–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller T, Galbraith M. The costs of occupational injury in the United States. Accid Anal Prev 1995;27:741–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reville R, Bhattacharya J, Sager L. Measuring the economic consequences of workplace injuries. Am J Ind Med 2001;40:452–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasiak R, Pransky G, Webster B. Methodological challenges in studying recurrence of low back pain. J Occup Rehabil 2003;13:21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wickizer T, Franklin G, Fulton-Kehoe D, et al. Improving quality, preventing disability and reducing costs in workers’ compensation healthcare. Med Care 2011;49:1105–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collie A, Pan Y, Britt H, et al. Coverage of work-related injuries by workers’ compensation in Australian general practice. Int J Work Comp 2011;3:1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Driscoll T, Mitchell R, Mandryk J, et al. Coverage of work related fatalities in Australia by compensation and occupational health and safety agencies. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruseckaite R, Clay F, Collie A. Second workers’ compensation claims: who is at risk? Analysis of WorkSafe Victoria, Australia compensation claims. Can J Public Health 2012;103:309–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cameron I, Rebbeck T, Sindhusake D. Legislative change is associated with improved health status in people with whiplash. Soine 2008;33:250–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feldstein A, Breen V, Dana N. Prevention of work-related disability. J Prev Med 1998;14:33–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Public Health Association Worker's compensation reform, adopted by APHA Governing Council, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ammendolia C, Cassidy D, Soklaridis S, et al. Designing a workplace return-to-work program for occupational low back pain: an intervention mapping approach. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:65. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-10-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sullivan M, Ward L, Tripp D, et al. Secondary prevention of work disability: community-based psychosocial intervention for musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:377–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Quinlan M, Mayhew C. Precariuos employment and workers’ compensation. Int J Law Psych 1999;22:491–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Restrepo T, Shuford H. Workers compensation and the aging workforce. In: (NCCI Research Brief). ed 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith C, Silverstein B, Bonauto D, et al. Temporary workers in Washington state. Am J Indust Med 2010;53:135–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feuerstein M. A multidisciplinary approach to the prevention, evaluation, and management of work disability. J Occup Rehabil 1991;1:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan M, Feuerstein M, Gatchel R, et al. Integrating psychosocial and behaviuoral interventions to achieve optimal rehabilitation outcomes. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:475–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.