Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the performance of the National Health Service (NHS) Health Check in identifying people at high risk of having or developing type 2 diabetes.

Design

Retrospective evaluation of the performance of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter (based on ethnicity, body mass index and blood pressure) in identifying people at risk for type 2 diabetes (glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥42 mmol/mol recorded within 3 months of their NHS Health Check).

Setting

Heart of Birmingham Primary Care Trust (HoB PCT).

Subjects

34 022 patients with a Read code in the general practitioners’ (GP) clinical record indicating that they had attended an NHS Health Check over the period April 2009 – February 2012.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure: proportion (%) of patients at risk of diabetes or non-diabetes hyperglycaemia not identified by a simple application of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter. Secondary outcome measures included sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV) and specificity of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter.

Results

In HoB PCT, the simple application of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter led to a failure to identify 1990/5968 (33.3% (95% CI, 31.2% to 35.4%)) of patients of known ethnicity at risk of having or developing diabetes (HbA1c≥42 mmol/mol). The NHS Health Check diabetes filter has a sensitivity of 66.8% (95% CI 65.7% to 68.0%), and the PPV was 41.1% (95% CI 40.1% to 42.1%). Specificity was 34.7% (95%CI 33.9% to 35.6%). Sensitivity and PPV of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter in the HoB PCT population are significantly greater for patients of Asian ethnic origin than for those of other ethnic backgrounds.

Conclusions

This evaluation, which was based on a large population sample, demonstrates that the NHS Health Check programme diabetes filter failed to identify a third of people at high risk of having or developing diabetes.

Keywords: Screening, Audit, Diabetes Mellitus, Public Health, Primary Care, Prevention

Article summary.

Article focus

The National Health Service Health Check programme (NHSHCP) was introduced in 2009 to encourage people to consider positive lifestyle changes and to improve case finding for vascular disease such as coronary heart disease and chronic kidney disease in the general population, aged 40–74 years, without diagnosed existing vascular disease. The NHSHCP includes assessment of risk of diabetes using a diabetes screening test called a filter (based on ethnicity, body mass index and blood pressure).

In the UK, people from the Indian subcontinent experience a higher incidence and prevalence of premature coronary heart disease , in part as a consequence of diabetes. It is particularly important that those at highest risk in this population subgroup are identified early.

This study, to evaluate the NHSHCP diabetes filter, was conducted in a population where people of South Asian origin represent the largest group (over 60%). The study involved a retrospective review of patients already identified as at high risk for diabetes (from the measurement of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) at the time of their NHS Check), with the outcome had the check relied solely on the use of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter.

Key messages

This evaluation, which was based on a large, high-risk population sample, demonstrates that the NHS Health Check programme diabetes filter failed to identify a third of people at actual risk of having or developing diabetes (defined as HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol).

Use of the current NHS Health Check diabetes filter may lead to a failure to identify a group of patients with normal body weight but at high risk from diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Further policy development is required along with more research into effective risk identification approaches for populations at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is possibly the first study of its size to evaluate the effectiveness of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter in clinical practice. It offers a unique opportunity to evaluate the performance of the filter in a large population sample with actual risk for diabetes assessed from a direct measurement of HbA1c.

HbA1c was not measured in all patients attending the NHS Health Check and for some patients, data on ethnicity were incomplete and/or data were not available for blood pressure and body mass index (further analysis revealed that the data were available but may have been recorded prior to the date of the NHS Health Check).

The evaluation involved the simple application of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter and did not take into account additional aspects of risk assessment such as family history of diabetes or other relevant comorbidities.

Introduction

According to the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) for England, in 2010, cardiovascular disease (CVD) was responsible for around one in three premature deaths (under 75) in men and one in five premature deaths in women. Coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke are the main causes of CVD mortality.1

In the UK, people from the Indian subcontinent experience a higher incidence and prevalence of premature CHD, in part as a consequence of diabetes; people from South Asian backgrounds have a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and they develop it on average 5 years earlier than white people.2 3 The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends that all people with diabetes be considered to be at high premature cardiovascular risk for their age unless they: are not overweight, are normotensive, have no evidence of microalbuminuria, are non-smokers, do not have a high-risk lipid profile and have no history of CVD and no family history of CVD.4

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) recently published guidance on risk identification and interventions for people at high risk of type 2 diabetes.5 There is no single accepted way of identifying people who are at risk of diabetes or who have existing undiagnosed diabetes. NICE recommends a two-stage process starting with either validated, computer-based risk assessment tools applied to demographic and routine data in clinical information systems for example, the Cambridge risk score,6 or validated self-assessment questionnaires such as FINDRISC7 or the Diabetes Risk Score.8 NICE states that this guidance can be used alongside the NHS Health Check programme.

The NHS Health (formerly vascular) Check programme (http://www.healthcheck.nhs.uk) was introduced in 2009 with the combined aims of improving life expectancy and reducing health inequalities by engaging with individuals to consider their modifiable risk factors and improved case finding through assessment of vascular risk in the general population aged 40–74 years without diagnosed existing vascular disease (table 1).

Table 1 .

NHS Health Check Programme exclusions with diagnosed existing vascular disease

| Atrial fibrillation | Hypertension |

| Chronic kidney disease (stages 3–5) | Hypercholesterolaemia |

| Coronary heart disease | Peripheral arterial disease |

| Diabetes | Stroke |

| Heart failure | Transient ischaemic attack |

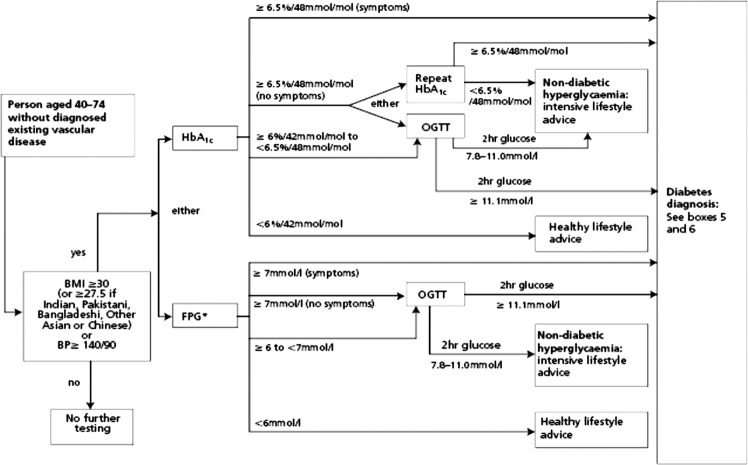

The NHS Health Check includes assessment of risk of diabetes using a diabetes screening tool called a filter (based on ethnicity, body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure) to identify those participants that should also receive a blood glucose test (either glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) or fasting plasma glucose). This is described diagrammatically in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic overview for identifying people at high risk of having or developing diabetes. Source: Putting Prevention First NHS Health Check: Vascular Risk Assessment and Management Best Practice Guidance (http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_098410.pdf).

Potentially, the diabetes filter will exclude people with diabetes with normal or low body weight. However, this two-stage screening procedure is considered pragmatic and is based largely on evidence from two population-based screening studies in the UK in Leicester, involving both the South Asian and White European populations in the city.9

Existing evidence regarding the relationship between weight and mortality in type 2 diabetes is conflicting. For example, in the WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes, there was no clear relationship between BMI and cardiovascular mortality.10 More recently, Carnethon et al11 found that, after adjustment, hazard ratios comparing normal weight participants with diabetes with overweight/obese participants for total, cardiovascular, and non-cardiovascular death rates were 2.08 (95% CI 1.52 to 2.85), 1.52 (95% CI 0.89 to 2.58), and 2.32 (95% CI 1.55 to 3.48), respectively.

Glycaemia, whether estimated by fasting glucose or HbA1c, has a continuous relationship with the risk of CVD.12

Recently, the WHO has stated that HbA1c alone can be used as a diagnostic test for diabetes provided that widely accepted criteria are met.13 An HbA1c of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) is recommended as the cut-off point for diagnosing diabetes (the SI unit for HbA1c is mmol/mol and is defined as mmol HbA1c/mol HbA0 + HbA1c). An HbA1c of 42–48 mmol/ml may indicate the presence of impaired glucose regulation (non-diabetes hyperglycaemia), and people with impaired glucose regulation are 5–15 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than those with normal glucose values.14 Diabetes prevention programmes have demonstrated that early intervention through lifestyle modification such as diet and increased physical activity can improve glucose tolerance and delay progression to diabetes in people with impaired glucose regulation.15

Heart of Birmingham Primary Care Trust (HoBPCT) is a high-risk population for type 2 diabetes, and a strategic clinical decision was made to request that general practitioner (GP) practices offered all those attending the NHS Health Check programme the measurement of HbA1c (without application of the filter), to establish directly an individual's risk of diabetes or non-diabetes hyperglycaemia. Utilising this unique set of population data, we conducted a study to evaluate retrospectively the effectiveness of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter in identifying people at known actual risk of developing diabetes (HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol).

Method

Heart of Birmingham Primary Care Trust (HoBPCT)

HoBPCT is a primary care trust area in inner city Birmingham covering a population of approximately 275 000. The main functions of primary care trusts are to understand and engage with their local population to improve health and well-being, and to commission a comprehensive and equitable range of high-quality and responsive health services. The HoBPCT area is characterised by a majority population from minority population groups (70% non-white). In HoBPCT, people from the Indian subcontinent represent the largest group (over 60%). Over the period 2008–2010, the average life expectancy for men in the HoBPCT area was 75 years compared with 78 years for England.

NHS Health Check programme

NHS Health Checks are largely carried out in primary care settings. Best practice guidance has been issued to guide local areas in the identification of appropriate patients and systems for call, recall and follow-up. Best practice guidance also describes standards for obtaining anthropometric measurements such as height and weight (from which to calculate BMI) and other measurements such as blood pressure and serum cholesterol for use in risk equations and risk assessment.16 Ethnicity is needed for diabetes risk assessment and should be recorded using the most recent Office for National Statistics categories that were first developed for the England and Wales Census in 1991. These categories have been expanded at each subsequent census (in 2001 and 2011).17

Study method

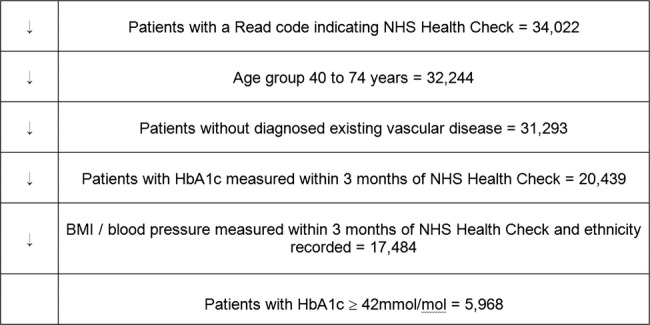

Data were obtained from GP records for 34 022 patients in HoBPCT that had received an NHS Health Check during the period from April 2009 to February 2012 (figure 2). Records were excluded if the patient was currently <40 or >74 years of age (n=1778) and therefore were outside the NHS Health Check age range, or if the patient at the time of their NHS Health Check had already been diagnosed with diabetes (n=951). Records were also excluded if data on HbA1c, blood pressure, BMI and ethnicity had not been recorded within 3 months of their health check (n=13 809).

Figure 2.

Study participants.

The remaining data were analysed to identify those patients who, at the time of their check, were found to be at high risk of diabetes (HbA1c of 42 mmol/ml or greater) (n=5968). Data on ethnicity, blood pressure measurement and BMI for these patients (from their NHS Health Check) were used to determine whether the diabetes filter would have correctly identified them as candidates for a blood glucose test. For the purpose of the NHS Health Check, patients whose ethnic origin puts them at a greater risk of diabetes include those of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, ‘Other’ Asian or Chinese origin. The diabetes filter is designed to detect patients at highest risk from within this group by targeting those with a BMI≥27.5. For all other ethnic groups, the filter operates at BMI≥30.

Ethical approval

Advice was obtained from the local NHS R&D Consortium. It was determined that this study represents an evaluation undertaken as part of an ongoing primary care trust (PCT) programme. For this reason, it was not necessary to have R&D approval from the consortium or a favourable ethical opinion from an NHS research ethics committee. In terms of the PCT data extraction facility, the PCT professional executive committee and GP locality leads previously provided approval for the vascular screening work programme, including evaluation and publication, and for AFB, as the PCT clinical lead, to view and utilise clinical data to improve patient management and population health.

Statistical methods

To assess the performance of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter, we calculated the proportion (%) of patients at risk of diabetes or non-diabetes hyperglycaemia (HbA1c of 42 mmol/mol or greater) for whom a simple application of the filter would not have led to blood glucose testing. We also calculated the sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV) and specificity of the NHS Health Check filter as a tool for identifying people at risk of diabetes or non-diabetes hyperglycaemia in the HoB population. All estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Application of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter

Combining blood pressure, BMI and ethnicity as filters, overall the NHS Health Check diabetes filter failed to identify the risk of diabetes in 33.3% (31.2% to 35.4%) of 5968 patients with HbA1c≥42 mmol/mol (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary performance of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter

| NHS Check patients (aged 40–74 years with HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol and BMI/BP recorded) | Total | BP normal (<140/90 mm Hg) BMI normal (<27.5 ‘Asian’, <30 ‘Other’) | Per cent at risk of diabetes not identified by application of the NHS Check diabetes filter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity ‘Asian’ | 3849 | 1207 | 31.3 (28.7 to 33.9) |

| Ethnicity ‘Other’ | 2119 | 783 | 36.9 (33.5 to 40.3) |

| All ethnicities | 5968 | 1990 | 33.3 (31.2 to 35.4) |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure.

Summary data on the sensitivity, PPV and specificity of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter in the HoB population are presented in table 3. It should be noted, however, that the NHS Health Check programme diabetes filter itself is not a formally accepted screening test for diabetes.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, positive predictive value and specificity of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter and risk for diabetes (HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol)

|

Sensitivity | |||

| Ethnicity | Test-positive and disease-positive patients (a) | Total disease-positive patients (b) | Sensitivity (a/b×100) |

| ‘Asian’ | 2649 | 3849 | 68.8% (67.2% to 70.3%) |

| ‘Other’ | 1341 | 2119 | 63.3% (60.5% to 64.6%) |

| All | 3990 | 5968 | 66.8% (65.7% to 68.0%) |

|

Positive predictive value | |||

| Ethnicity | Test-positive & disease- positive patients (a) | Total test-positive patients (c) | Positive Predictive Value (a/c×100) |

| ‘Asian’ | 2649 | 5324 | 49.7% (48.4% to 51.0%) |

| ‘Other’ | 1341 | 4376 | 30.6% (29.2% to 32.0%) |

| All | 3990 | 9700 | 41.1% (40.1% to 42.1%) |

|

Specificity | |||

| Ethnicity | Test-negative & disease- negative patients (d) | Total disease-negative patients (e) | Specificity (d/e×100) |

| ‘Asian’ | 1793 | 5221 | 34.3% (33.0% to 35.6%) |

| ‘Other’ | 2208 | 6295 | 35.1% (33.9% to 36.3%) |

| All | 4001 | 11516 | 34.7% (33.9% to 35.6%) |

(a) Patients with blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg and/or body mass index (BMI) ≥27.5/30.0 and HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol.

(b) Patients with HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol.

(c) Patients with blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg and/or BMI ≥27.5/30.0.

(d) Patients with blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg and/or BMI <27.5/30.0 and HbA1c <42 mmol/mol.

(e) Patients with HbA1c <42 mmol/mol.

In the Heart of Birmingham population, as a tool for identifying people at risk of diabetes, the NHS Health Check diabetes filter has a sensitivity of approximately 67%. PPV is 41%. This means that only two-thirds of those at risk for diabetes would have been identified as candidates for blood glucose testing and that, of all the patients identified as being at risk for diabetes, less than half would have been found to be at risk following blood glucose testing. Sensitivity and PPV of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter in the HoB population are significantly greater for patients of ‘Asian’ ethnic origin than those of other ethnicities (sensitivity 68.8% (67.2% to 70.3%) vs 63.3% (60.5% to 64.6%), PPV 49.7% (48.4% to 51.0%) vs 30.6% (29.2% to 32.0%)). The NHS Health Check diabetes filter has a specificity of approximately 35%, meaning that in the Heart of Birmingham population, two-thirds of people that were not at risk for diabetes would have been identified by the filter as requiring a blood glucose test.

Subgroup analysis

The performance of the diabetes filter was reviewed separately in men and women and the results are included in table 4. The diabetes filter failed to identify a greater proportion of men than women at risk for diabetes (37.8% (36.1% to 39.6%) vs 28.7% (27.1% to 30.3%)).

Table 4.

Performance of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter according to gender

| NHS Check patients aged 40–74 years with HbA1c ≥ 42 mmol/mol and BMI/BP recorded | Total | Blood pressure normal (<140/90 mm Hg) BMI normal (<27.5 ‘Asian’, <30 ‘Other’) | Per cent at risk of diabetes not identified by application of the NHS Check diabetes filter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||

| Ethnicity ‘Asian’ | 1894 | 692 | 36.5 (34.4 to 38.7) |

| Ethnicity ‘Other’ | 1071 | 439 | 41.0 (38.1 to 44.0) |

| All ethnicities | 2965 | 1121 | 37.8 (36.1 to 39.6) |

| Female | |||

| Ethnicity ‘Asian’ | 1955 | 517 | 26.4 (24.5 to 28.4) |

| Ethnicity ‘Other’ | 1047 | 344 | 32.8 (30.1 to 35.8) |

| All ethnicities | 3002 | 861 | 28.7 (27.1 to 30.3) |

Asian ethnicity

Owing to the increased risk for diabetes in the South Asian population, the NHS Health Check diabetes filter was tested at the lower threshold for BMI (23.0 kg/m2) in the ‘Asian’ subgroup. Results in terms of sensitivity, PPV and specificity of the diabetes filter at this BMI threshold are presented in table 5.

Table 5.

Sensitivity, positive predictive value and specificity of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter (Asian BMI ≥23.0) and risk for diabetes (HbA1c≥42 mmol/mol)

| Sensitivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Test-positive & disease- positive patients (a) | Total disease-positive patients (b) | Sensitivity (a/b×100) |

| ‘Asian’ | 3632 | 3849 | 94.4% (93.6% to 95.0%) |

|

Positive predictive value | |||

| Ethnicity | Test-positive & disease- positive patients (a) | Total test-positive patients (c) | Positive predictive value (a/c×100) |

| ‘Asian’ | 3632 | 8226 | 44.1% (43.1% to 45.2%) |

|

Specificity | |||

| Ethnicity | Test-negative & disease- negative patients (d) | Total disease-negative patients (e) | Specificity (d/e×100) |

| ‘Asian’ | 632 | 5221 | 12.1% (11.2% to 13.0%) |

(a) Patients with blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg and/or body mass index (BMI) ≥23.0 and HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol.

(b) Patients with HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol.

(c) Patients with blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg and/or BMI ≥23.0.

(d) Patients with blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg and/or BMI <23.0 and HbA1c <42 mmol/mol.

(e) Patients with HbA1c <42 mmol/mol.

Reducing the BMI threshold to ≥23 improves the performance of the filter in identifying Asian patients at risk for diabetes from approximately 70% to 95%. However, this improvement in the sensitivity of the filter is offset by a reduction in PPV and, more significantly, specificity. As a result, many more patients would be subjected unnecessarily to blood glucose testing.

Study limitations

Data were available only for those individuals that had responded positively to the invitation to attend an NHS Health Check. The study population was therefore, to a degree, self-selected; however, the fact that these probably represent the more motivated, health-seeking members of the population means that those with the greatest disease burden were potentially under-represented. Had the latter been included, it is likely that a greater proportion of people at risk for diabetes would have been identified initially, although the effectiveness of the diabetes filter is unlikely to have changed. Of the 31 293 eligible patients that received an NHS Health Check, ethnicity, HbA1c, BMI and blood pressure were not recorded contemporaneously in 44.1% (13 809/31 263) of patients who were thus excluded. The population in HoBPCT is relatively homogeneous, and unless this resulted in some significant selection bias, this is unlikely to have impacted on the outcome of the study and a relatively large population sample was retained.

Discussion

According to the charity Diabetes UK, by 2025, there will be more than 5 million people with diabetes in the UK and most of these will be type 2 diabetes.18 In 2002, the UK Department of Health estimated that 5% of total NHS expenditure is used for the care of people with diabetes. This figure is now believed to be closer to 10% of total NHS expenditure, which equates to £9 billion/year.19 Early diagnosis of diabetes, good glycaemic control and management of other cardiovascular risk factors have been shown to reduce the incidence of the macrovascular and microvascular disease complications that contribute the most to the disease burden.20 21 However, early identification of the risk of developing diabetes and intervention to reduce the incidence of diabetes are increasingly urgent and important strategies.

In 2002, in the USA, screening guidelines were proposed by the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus.22 Although testing is not recommended in the general population, screening is recommended for those 45 years of age and older; with repeated testing every 3 years if results are normal. Screening is also recommended at younger ages or at more frequent intervals for those who have one or more diabetes risk factors. Dallo and Weller23 identified that all the risk factors included in the screening guidelines had a strong association with diabetes; having hypertension or a positive family history of diabetes doubled the risk of having diabetes while age, obesity, a poor lipid profile, and gestational diabetes more than doubled the risk. Risk increased with an increase in BMI, and it was apparent that being ‘overweight’ was a significant risk factor without the presence of obesity. Although these guidelines have been widely endorsed, one-third of cases are undiagnosed and complications at the time of diagnosis indicate that disease may have been present for several years, suggesting that either screening is not effective or that the guidelines are not being followed.

In the UK, the National Screening Committee has determined against screening the general adult population for diabetes, while recognising the need for a vascular risk management programme that includes diabetes (http://www.screening.nhs.uk/diabetes). In 2009, in response to this policy and the increasing human and healthcare burden from diabetes, the Department of Health in England introduced the NHS Health Check programme, a vascular ‘check’ for people aged 40–74 years without diagnosed existing vascular disease. The NHS Health Check assesses 10-year risk of CVD, combining patient-level data (including physiological and biochemical tests and anthropometric measurements) in an approved risk calculator. It also employs a diabetes filter based on known risk factors (blood pressure, BMI and ethnicity) to identify patients at high risk for undiagnosed diabetes who should undergo blood glucose testing.

In our study, the NHS Health Check diabetes filter failed to identify a third of patients at high actual risk for diabetes (defined as HbA1c ≥42 mmol/mol). Conversely, two-thirds of those that were identified by the filter as being at high risk had HbA1c <42 mmol/mol. PPV for those patients identified by the filter as being at risk was 41%. Heart of Birmingham represents a high prevalence population for diabetes, and the PPV of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter may be reduced in lower prevalence populations.

The WHO International Classification of Overweight was developed in 1993 and is based on a BMI cut-off point of 25 kg/m2. In 2002, a WHO expert consultation was convened to consider the interpretation of recommended BMI cut-off points for determining overweight and obesity in Asian populations.24 It was suggested that Asian populations have different associations between BMI, percentage of body fat and health risks than do European populations; however, the cut-off point for observed risk varies for different Asian populations. The consultation agreed that the WHO BMI cut-off point for overweight (25 kg/m2) should be retained as an international classification, while agreeing to the existence of further potential public health action points (23.0, 27.5, 32.5 and 37.5 kg/m2) along the continuum of BMI.

We tested the BMI threshold for screening for diabetes in people of Asian ethnic origin in line with the WHO recommendations. Using a cut-off point of BMI ≥23.0 for Asian patients (rather than ≥27.5 as per the NHS Health Check) dramatically increased the sensitivity of the diabetes filter in detecting those at risk of diabetes (to approximately 95%). However, as a consequence, were this strategy to be adopted, the specificity of the filter would reduce to 12% and many more patients who were not at risk would be subjected to blood glucose testing.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines on risk identification and intervention for people at high risk of type 2 diabetes are recommended for implementation alongside the NHS Health Check Programme.5 However, in the guidelines, risk identification relies on the use of validated computer-based risk assessment tools or validated self-assessment questionnaires and extends to groups other than those aged 40–74 years, to include people of South Asian and Chinese descent aged 25–39 years (except for pregnant women) and other adults with conditions that increase the risk of type 2 diabetes such as CVD and gestational diabetes. NICE recommend considering a blood test for those aged 25 years or more of South Asian or Chinese descent whose BMI is greater than 23.

Several risk scores have been developed to predict diabetes risk. These are based on a core set of readily available non-invasive measures, for example, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure, family history and a measure of adiposity (either BMI or waist circumference) or on data from questionnaires.25 More sophisticated risk scoring methods include fasting plasma glucose; however, this reduces the practicality of the approach. Full prediction models have been shown to be more discriminatory than single risk factors for predicting the risk of diabetes; however, most of these risk equations have been developed in research populations and several authors have identified that recalibration is needed before these equations can be used to estimate the risk of diabetes for individual patients.25 26

Abbasi et al26 conducted a systematic review to identify existing risk prediction tools for diabetes including both basic and ‘extended’ tools, the latter including biomarkers such as blood glucose concentration. Twelve basic and 13 extended models were subsequently validated in a random sub cohort (n=2506) of a Dutch prospective cohort study (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC-NL). In the majority of cases, the prediction tools overestimated the absolute risk of diabetes in the validation population. After adjustment for population incident risk, the performance of the prediction tools improved; however, on the whole, significant deviations between estimated and observed risk remained. The authors concluded that prediction tools developed in study populations can be calibrated for use in external populations and are effective in identifying those at high risk but are less reliable for predicting absolute risk of diabetes.

Conclusion

This evaluation, which was based on a large population sample, demonstrates that the NHS Health Check programme diabetes filter failed to identify a third of people that are at high risk of having or developing diabetes. This is a unique set of data and possibly the first evaluation of the NHS Health Check diabetes filter in a clinical practice setting whereby the actual risk for diabetes had been obtained directly from measurement of HbA1c.

Given the availability of such a unique dataset, further work will be undertaken to demonstrate the impact on sensitivity and PPV by varying the current NHS Health Check thresholds for BMI and blood pressure. Given the depth of the available data, it would also be of value to assess whether or not the use of other patient parameters such as waist circumference might improve the performance of the filter. Further analysis will be undertaken to determine the overall cost effectiveness of direct measurement of HbA1c for all people in the NHS Health Check programme.

The NHS Health Check diabetes filter is intended to be both pragmatic and feasible in clinical practice. However, computer-based risk scoring tools for diabetes that have been validated for use in the UK population (as advocated by NICE) may be more effective in risk identification for diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JW and AFB conceived the idea of the study. SS, JW and AFB were responsible for the design of the study. SS was responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. SS, JW and AFB provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by SS and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. AFB was responsible for the acquisition of the data, and SS, AFB and JW contributed to the interpretation of the results.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: AFB has received payments from Graphnet Ltd for providing advice on patient views of their electronic records (Graphnet was the system used to provide the data on which this study is based) and from Heart of Birmingham PCT for presentations about the Health Check to general practitioners and practice nurses. He is a member of Diabetes UK, which argues in favour of systematic case finding for diabetes, and is also the clinical lead for reduction in cardiovascular deaths in Heart of Birmingham PCT.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.CMO annual report: volume 1, 2011 On the state of the public's health Department of Health http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/11/cmo-annual-report/ (accessed 1 Dec 2012).

- 2.Balarajan R. Ethnicity and variations in mortality from coronary heart disease. Health Trends 1996;28:45–51 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diabetes key facts, March 2006. Yorkshire and Humber Public Health Observatory. http://www.yhpho.org.uk/resource/item.aspx?RID=8872 (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 4.NICE Clinical Guideline: type 2 diabetes (CG66) The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=download&o=40803 (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 5.Preventing type 2 diabetes: risk identification and interventions for individuals at high risk (PH38) National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . July 2012.

- 6.Griffin SJ, Little PS, Hales CN, et al. Diabetes risk score: towards earlier detection of type 2 diabetes in general practice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000;16:164–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FINDRIC (Finnish Diabetes Risk Score) http://www.diabetes.fi/english/risktest (accessed 10 Sept 2012).

- 8.Diabetes Risk Score Diabetes UK. http://www.diabetes.fi/english/risktest/http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Riskscore/ (accessed 10 Sept 2012).

- 9.The Handbook for Vascular Risk Assessment, Risk Reduction and Risk Management UK National Screening Committee 2008. http://www.screening.nhs.uk/publications (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 10.Chaturvedi N, Fuller JH, WHO MSVDD Study Group Mortality risk by body weight and weight change in people with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1995;18:766–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnethon MR, De Chavez PJ, Biggs ML, et al. Association of weight status with mortality in adults with incident diabetes. JAMA 2012;308:581–90 (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coutinho M, Gerstein HC, Wang Y, et al. The relationship between glucose and incident cardiovascular events. A meta-regression analysis of published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals followed for 12.4 years. Diabetes Care 1999;22;233–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of Diabetes mellitus. World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/report-hba1c_2011.pdf (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 14.Chatterton H, Younger T, Fischer A, et al. Risk identification and interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes in adults at high risk: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2012;345:e4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007;334:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putting prevention first. NHS Health Check: vascular risk assessment and management best practice guidance. Department of Health 2009. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_097489 (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 17.2005. A practical guide to ethnic monitoring in the NHS and social care. DH/Health and Social Care Information Centre/NHS Employers.

- 18.Diabetes in the UK 2010: key statistics on diabetes Diabetes UK. (http://www.diabetes.org.uk) (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 19.National Diabetes Information Service NHS Diabetes/Yorkshire and Humber Public Health Observatory. http://www.yhpho.org.uk/resource/view.aspx?RID=102082 (accessed 13 Aug 2012).

- 20.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, et al. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. New Engl J Med 2003;348:383–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turnbull F, Abraira C, Anderson R, et al. Intensive glucose control and macro vascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:2288–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO expert consultation. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2002. 25:s5-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dallo FJ, Weller SC. Effectiveness of diabetes mellitus screening guidelines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:10574–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO expert consultation Appropriate body—mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004;363:157–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buijsse B, Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, et al. Risk assessment tools for identifying individuals at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Am J Epidemiol 2011;33:46–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbasi A, Peelen LM, Corpeleijn E, et al. Prediction models for risk of developing type 2 diabetes: systematic literature search and independent external validation study. BMJ 2012;345:e5900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.