Abstract

Background

The work incapacity of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) ranges between 3% and 50% in Europe. In many countries, work incapacity is difficult to quantify. The work ability index (WAI) is applied to measure the work ability in workers, but it is not well investigated in patients.

Aims

To investigate the work incapacity in terms of absence days in patients with AS and to evaluate whether the WAI reflects the absence from work.

Hypothesis

Absence days can be estimated based on the WAI and other variables.

Design

Cross-sectional design.

Setting

In a secondary care centre in Switzerland, the WAI and a questionnaire about work absence were administered in AS patients prior to cardiovascular training. The number of absence days was collected retrospectively. The absence days were estimated using a two-part regression model.

Participants

92 AS patients (58 men (63%)). Inclusion criteria: AS diagnosis, ability to cycle, age between 18 and 65 years. Exclusion criteria: severe heart disease.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Absence days.

Results

Of the 92 patients, 14 received a disability pension and 78 were in the working process. The median absence days per year of the 78 patients due to AS alone and including other reasons was 0 days (IQR 0–12.3) and 2.5 days (IQR 0–19), respectively. The WAI score (regression coefficient=−4.66 (p<0.001, CI −6.1 to −3.2), ‘getting a disability pension’ (regression coefficient=−106.8 (p<0.001, 95% CI −141.6 to −72.0) and other not significant variables explained 70% of the variance in absence days (p<0.001), and therefore may estimate the number of absence days.

Conclusions

Absences in our sample of AS patients were equal to pan-European countries. In groups of AS patients, the WAI and other variables are valid to estimate absence days with the help of a two-part regression model.

Keywords: Rehabilitation Medicine, Rheumatology, Occupational & Industrial Medicine, Pain Management, questionnaire

Article summary.

Article focus

To measure the incapacity for work in terms of absence days in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in Switzerland.

To evaluate whether the work ability index (WAI) reflects the absence from work.

Key messages

Incapacity for work in a Swiss cohort of AS patients is similar to the results from other European studies.

This study shows that the WAI score, together with specific variables, can be used in AS patients to calculate their absence days.

Measuring absence days with the help of the WAI is feasible and cost saving.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study showed that the WAI is feasible not only in prevention but also in a clinical setting for patients with AS.

We took into account that the data are skewed and checked the goodness of fit of the regression model by splitting half the group.

Perhaps patients with a high motivation to influence their health were over-represented in this study. This could lead to an underestimation of the absence days.

Introduction

People affected with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are impaired in their daily living activities. This is a problem for both the patients and the society in terms of the high costs associated with the loss of productivity. The magnitude of the disability should be determined in order to manage AS patients with restrictions in the work status effectively. The range of employment in different countries varies widely from 34% to 96%, and the incapacity for work ranges from 3% to 50% depending on the disease duration. Prevalence of AS in western Europe is estimated at 0.86%1 2 to 1.4%.3 Incapacity to work is higher in patients affected with AS than in the general population. Mean national sick leave per working individual annually has been measured to be between 7 and 16 days in the Netherlands, France and Belgium,4 in comparison to 12–46 days of sick leave per patient with AS per year5 in the same countries. In Switzerland, two studies about the work status of AS patients show different numbers regarding the incapacity for work. In one study, 42.5% of patients reported an occasional incapacity for work due to AS, whereas 13.5% were permanently disabled and received a partial (10.2%) or full disability pension (3.3%). Days of sick leave were not reported.6 In an earlier study, the point estimate of the work ability was measured at 97.3% and disability at 2.7%.7 This may reflect that the evaluation of the work status is rather complicated because of the different possible endpoints or definitions of the work ability.5 In Switzerland and in most of the other countries, reliable data about absence days do not exist.8 But in musculoskeletal rehabilitation, there is a growing demand for evaluating relevant outcome parameters.

In various studies, information about sickness absence is gathered from the registered data of companies9 or from the civil service register.10 But these measurements are not validated. Nevertheless, there is no direct access to absence data in many countries, and moreover, to gather such information in daily practice is too costly and hardly feasible. Absence days are a composite of full-time or part-time work, full or partial work disability, full or partial performance because of illness. Questionnaire-based evaluations of absence days are complicated, time-consuming and possibly not valid. Additionally, it remains unclear whether absences are due to the disease or due to comorbidities. An alternative is a comprehensive person-to-person assessment. In Switzerland, the loss of one working day costs about 600 euro on average,11 and therefore work loss is a significant cost factor in back and musculoskeletal disorders. To our knowledge, only one validated questionnaire for patients with AS12 exists, however, that takes into account only to a small part the aforementioned complicated construct of the incapacity for work. The time span of this questionnaire covers the past 7 days. However, such a short period may not reflect adequately the course of a disease such as AS. There is another assessment for working ability, the so-called ‘work ability index’ (WAI),13–15 which is well investigated in the work environment and in occupational healthcare, where it has been shown to be predictive15 in terms of future incapacity for work and disability pension. In a big study with 40 000 nurses, its internal reliability with a Cronbach's α of 0.72 has been proved to be satisfactory and the concurrent validity expressed by correlations to other questionnaires showed consistent and expected correlation coefficients r of around ±0.5.16 The test–retest reliability revealed acceptable values with a percentage of observed agreement of 66% between the baseline measurement and the second measurement which was 4 weeks later. At the group level, the WAI is stable and did not show any significant difference in the mean between the points of time.17 Recently, the WAI has also been used as an outcome measurement in some intervention and cross-sectional studies with groups of patients (instead of workers) with different diseases, for example, musculoskeletal disorders,18 heart disease, hypertension,19 psychiatric disorders,20 rheumatoid arthritis21 or osteoarthritis.22 In all these studies, the WAI has been shown to be feasible and validly assesses the ability to work. So far, the WAI has not been applied to patients with AS.

The aim of this study was to investigate how big the problem of incapacity to work is in a subgroup of people with AS in Switzerland. A secondary aim was to develop a simple method to measure absence days to avoid the use of complicated and time-consuming assessments or inaccurate registers. Therefore, the hypothesis was that the WAI, in combination with other variables, could potentially serve as a simple instrument for measuring absence days in AS patients.

Study population and methods

Participants

The participants for this study were all AS patients taking part in a cardiovascular training study for which the sample size was computed to detect the effect of the training. The patients were recruited from the national Ankylosing Spondylitis Association and from the rheumatology outpatient facilities in our country in 2008/2009. The last follow-up of the intervention was in 2010. Inclusion criteria for the cardiovascular training intervention and thus this study were: AS diagnosis following the modified New York criteria, the ability to cycle, sufficient German language ability (for questionnaires), age between 18 and 65 years, willingness to follow the study protocol and an informed consent. Chronic heart failure and functional NYHA Classes III and IV were criteria for exclusion. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and the patients provided written informed consent. All patients were randomised to either the cardiovascular training or an attention control.

Design

We investigated retrospectively the dimension of incapacity for work with questions about the work status (QW) and evaluated the feasibility of an estimation of absence days by the WAI and other variables. For the latter, a two-part regression model was built. In the second part of this model, the absence days which were computed by the QW were included as dependent variable, and the WAI with other variables were introduced as independent variables.

Measurements of the WAI-study

A comprehensive assessment was conducted before the cardiovascular training. The measurements included the WAI and additional questions about the work status (QW) which were gathered retrospectively.

The WAI is a 13-item questionnaire about (1) the work conditions, (2) the perception of the present health condition and (3) the perceived prognosis for work. The WAI is an assessment of the general health, and measures the work ability in terms of all health conditions. A part of the WAI deals with a recall period for the last 12 months. One item of the WAI collects the number of current diseases or comorbidities. The WAI is easy to use and takes about 10 min to fill in.13 15 The scores range from 7 to 49 points, with 49 points describing the best ability to work. The rules to compute the scores are described in detail.13 The scores of the WAI can be divided into four categories: 7–27 = poor, 28–36=moderate, 37–43=good, 44–49 = excellent ability to work.

A second questionnaire about the work status (QW) with the aim to calculate absence days was created with different substantial questions about the work ability. In contrast to the brief WAI, the comprehensive QW ought to reveal more accurate information on the complex construct of the incapacity for work. We selected the questions of the QW by means of another study,23 addressing the disability to work, and on the basis of the clinical experience on determining the work ability. The items of the QW include working tasks (mental, physical or mixed), full-time or part-time work, full or partial work disability during the last year, sick days during the last year, duration of the work disability, reasons for the incapacity for work (AS vs other health reasons) and disability leading to financial support.

Procedure

The absence days were computed by means of the QW: the work disability for the previous year is expressed in ‘days off work due to health reasons’. The QW measures absence days due to the following reasons: AS alone, not AS-related health conditions or AS together with other health problems. Only working days are counted, whereas weekends and holidays are not included. The work disability is composed of the number of complete sick days and of the partial presence at work due to health reasons. For instance, 30% incapacity for work in a full-time job during a distinct period is converted into the corresponding number of sick days. The numbers are adjusted for part-time work, for example, if someone is employed for 50%, then the days of sick leave consist of only half of the absence days of those on full-time employment. The work disability, days off work and early retirement due to AS, in contrast to other health problems, were considered separately from each other as was also done in a review.5 One could argue that the WAI contains an item that assesses self-reported sick leave over the previous 12 months; therefore, it would not be necessary to measure the absence days with the more complicated QW. But Radkiewicz and Widerszal-Bazyl16 pointed out that the aforementioned item of the WAI should be excluded from the WAI, because there is no substantial relationship between this item and the overall score. Furthermore, this item diminishes the internal validity, and thus the QW was introduced to measure absence days.

Statistics

The data were checked for normal distribution. Appropriate parametric and non-parametric statistics, depending on the distribution, were applied. Non-parametric statistics were used to compare the distributions for the demographic variables and the absence days across the groups. The level of significance was set at α = 0.05. With regard to the main aim of the study, descriptive statistics were used to depict demographic data, the absence days (on the basis of the QW) and the WAI score. The WAI score and the absence days in the QW were correlated to evaluate the relation and the concurrent validity between the two questionnaires. Pertaining to the second aim of the study, namely to get a simple way to measure absence days, a two-part regression model was conducted. If the dependent variable has many zero-values, like in our study the cases without absence days, two-part models are suitable to get unbiased estimators and therefore unbiased prediction for the values of the dependent variable. First, we performed a logistic regression analysis to assess the logarithmic odds for the predicting variables which can be used to compute the probability for a patient to have absence days. The logistic regression model is: Logit = b0 + b1x1+b2x2+…+b5x5. The logit of one observation ‘i’ for the absence days can be transformed in the logarithmic odds (exp(Logit)), and in the second step, the probability for absence days is computed by dividing the ‘odds’ through (odds +1). In the second step of the two-part model we estimated with a multiple-linear regression analysis the number of absence days in patients with absences. By multiplying the probability of the logistic regression with the result of the linear regression, an estimation of the absence days is obtained. These regression models allow the estimation of the absence days as a constructed value in prospective studies. The number of absence days calculated by the QW represents the dependent variable in the multiple-regression model. Age and gender were assessed as confounding variables. The statistical software PASW statistics (V.18) was used for the analysis.

Results

Of the 185 eligible patients, 77 refused to participate and 16 were excluded due to the exclusion criteria. Table 1 shows the demographic variables and AS-specific functional health indices like the Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI; perceived disease activity),24 BASFI (physical function),25 Bath AS Metrology Index (spinal mobility)26 and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score(CRP) (calculated by using parameters from BASDAI and C reactive protein values).27 Further, table 1 shows the work status and the mental or physical job demands of the 92 patients in the working age who were included. Four of these received a full pension (3 patients because of AS, 1 because of other reasons) and 10 a partial disability pension. The remaining 78 individuals (84.7%) were still in the working process and worked 88.9% of a full-time job per year. There were 34 (37%) people without any absence days. Table 2 shows the WAI scores and the absence days computed on the basis of the QW. Where the data are skewed, median values are presented in table 2. A patient may have absence days due to (1) AS alone, (2) other health problems (eg, depression) or (3) both. Therefore, the median is zero for (1) and (2), but bigger than zero for (3). There were no missing values in the main variables.

Table 1.

Baseline variables (n=92)

| Overall, n=92 | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 46.34 (11.15) |

| Gender | |

| Men (%) | 58 (63.0) |

| Women (%) | 34 (37.0) |

| Duration in years since AS diagnosis Mean (SD) | 14.55 (12.74) |

| BASDAI (0–10), mean (SD) | 3.45 (2.0) |

| BASFI (0–10), mean (SD) | 2.4 (2.0) |

| BASMI (0–10), mean (SD) | 2.85 (2.0) |

| ASDAS(CRP), mean (SD) | 6.95 (9.25) |

| Number of current diseases | |

| AS alone | 22 |

| +1–2 | 45 |

| +>2 | 25 |

| Education, n (%) | |

| ≤12 years | 60 (65.2) |

| >12 years | 26 (28.3) |

| Not known | 6 (6.5) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Paid work | 68 (73.9) |

| Unpaid work | 6 (6.5) |

| Unemployed | 4 (4.4) |

| Partial disability pension | 10 (10.9) |

| Full disability pension | 4 (4.3) |

| Job demands (n=78, no disability pension) | |

| Physical | 11% |

| Mental | 41% |

| Both | 48% |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASDAS(CRP), Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (calculated with C reactive protein values); BASDAI, Bath AS Disease Activity Index; BASFI, The Bath AS Functional Index; BASMI, Bath AS Metrology Index.

Table 2.

Absence days (AD) and WAI-scores for the patients in the working age

| People with >0 absence days, n=58 (63%) | Due to | All patients in the working age (n=92) | Patients without disability pension (n=78) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absence days during the last year, median (IQR) | 24 (6.5–127.7) | AS alone | 0 (0–37.8) | 0 (0–12.3) |

| Other health problems | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | ||

| AS and other health problems | 4.5 (0–61.1) | 2.5 (0–19) | ||

| WAI, mean (SD) | – | – | 34.18 (9.77) | 35.93 (9.29) |

Absence days measured by the QW.

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; WAI, work ability index.

Although the data were skewed, we also calculated the mean values for absence days, expressed as the percentage of the working time per year. This will allow a comparison of the absence days to those of other studies. The 78 patients had a mean of 17.9 absence days (SD±43.7) due to AS only, which is equivalent to 8.1% incapacity for work. Owing to other health reasons, an incapacity for work of 2.5% was calculated. When the 14 patients receiving a disability pension were included (n=92), the mean absence days due to all reasons was 47.9 days (SD±79.1). These correspond to a disability of 21.6%. The 10 patients with a partial disability pension were still partially in the working process and had a mean working time of 41% (SD±31).

Sensitivity analysis: It is unknown whether patients with a full or a partial disability pension would work 88.9% of the annual working time, if they would not receive any disability pension. Hence, the percentage of the disability for this group (n=92), presuming that the patients would work 100% or 80% of a full-time job, was calculated. Under this presumption, the disability due to all health problems would be 19.2% and 24%, respectively.

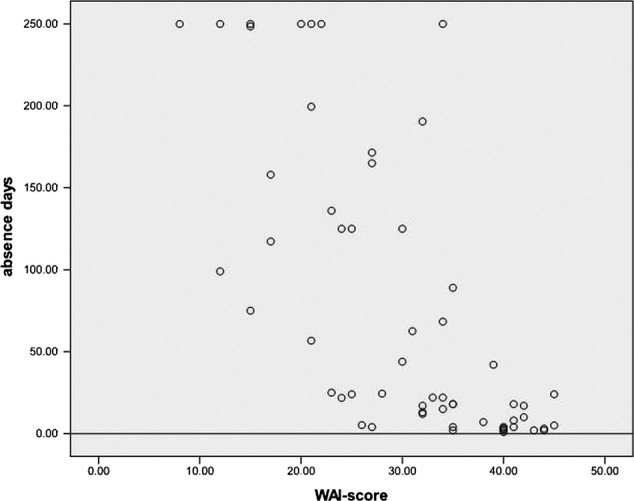

The Spearman correlation between the WAI and the absence days on the basis of the QW, which expresses the concurrent validity, was −0.736 (p<0.001) for all of the 92 patients. The scatter plot revealed an overrepresentation of cases without absence days. However, a range correlation should not be analysed, if there are tied ranks such as the multiple cases with zero absence days. Therefore, the correlation was calculated for the subgroup of AS patients which had at least one absence day per year due to all health problems (n=58), irrespective of getting a disability pension. The correlation reveals an r=−0.755 with a significant p value of p<0.001 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of the work ability index and absence days for the subgroup with absence days (n=58).

Secondary study aim

The results of the logistic regression analysis to estimate the logarithmic odds for a person with AS to have absence days are shown in table 3. The variables ‘age’ and ‘WAI’ were found to be significant predictors in this multiple-logistic regression model. The assumption of linearity of the logits has been met and the residual statistics showed acceptable values. A multiple-linear regression analysis with the QW as a dependent variable was performed. All significant baseline variables, namely the WAI score, the ‘number of additional co-morbidities’ that were collected by the WAI (split into values up to 2/>2), age and disability pension (yes/no) as well as gender, were included in the model. The multiple-regression analysis revealed that 70% of the variance in the dependent variable absence days (measured by the complex QW) can be explained by the independent variables of age, gender, WAI, the number of diagnoses and a disability pension (table 3). However, only WAI and ‘getting a disability pension’ significantly contributed to the model. Thus, the absence days of an AS patient can be estimated by multiple regression with the unstandardised regression coefficients: y=b1*x1+b2*x2+…+bn*xn+a, where y is the estimated value of the absence days, n is the number of independent variables, x1 to xn are the independent variables (age, gender, WAI, the number of diagnoses and getting a disability pension), and a is a constant (table 3). Owing to the skewed distribution of the absence days and the WAI, we verified our presented regression model by splitting the sample into two halves. We estimated each with the shown regression model. We then correlated the estimates and the true values of each group. The result of this was squared and compared with the R2 of the same group (results not shown). The squared correlation and the R2 should be similar in order to confirm that the regression model is capable of predicting the absence days of another sample quite accurately (eg, the other half of the group). The differences were 0.18 for the first half and 0.05 for the second half, indicating a good fit of the model.

Table 3.

Two-part model: multiple logistic and multiple-linear regression analysis

| Model | Independent variables | B coefficients | Standardised regression coefficients (β) | Significant p value | 95% CI for B lower/upper |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple logistic regression Predicted variable: absence days | Constant | 11.039 | 0.000 | 6.14 | 15.93 | |

| Age | −0.065 | 0.013 | −0.116 | −0.014 | ||

| WAI | −0.203 | 0.000 | −0.293 | −0.113 | ||

| Multiple linear regression Predicted variable: number of absence days | Constant | 427.2* | – | 0.000 | 317.32 | 537.08 |

| Disability pension† | −106.81* | −0.52 | 0.000 | −141.60 | −72.02 | |

| WAI | −4.66* | −0.51 | 0.000 | −6.13 | −3.18 | |

| Age | −0.498* | −0.07 | 0.429 | −1.75 | 0.76 | |

| Gender | −10.71* | −0.06 | 0.414 | −36.82 | 15.40 | |

| N° of diagnoses‡ | 10.24* | 0.06 | 0.461 | −17.45 | 37.93 | |

The logistic regression has a Nagelkerke R=0.458, the Hosmer and Lemeshow test was not significant (p=0.09), the Omnibus test was very small (p=0.000).

For the multiple regression, the R2 was 0.724, R2 adjusted 0.7, the model is significant with p<0.001.

*Unstandardised regression coefficients (B).

†Disability pension (yes/no).

‡Number of diagnoses (up to 2/>2).

Discussion

Key results

Individuals without a disability pension had an 8.1% incapacity for work, if it was solely due to AS. The absence days increased by 2.5% when AS patients, who have had incapacity for work due to other health reasons, were included. The percentage of absences due to AS and other health reasons, including the individuals receiving a disability pension, was 21% as evaluated by the QW. Multiple-regression analysis explained 70% of the variance of the absence days. The two variables ‘WAI’ and ‘disability pension’ made a significant contribution to this model. Thus, the WAI, in combination with other variables, can serve as a simple instrument for measuring absence days in the various groups of AS patients.

Discussing important differences to other studies

The results regarding the absences of a group of AS patients who underwent cardiovascular training are comparable to the findings of another Swiss cohort.6 But the number of absence days in our study is slightly lower than in the review by Boonen et al.5 Higher rates of disability pension are found in other studies.28–31 The differences in the ability to work in different studies are dependent on several factors such as disease duration and activity, the perceived self-efficacy to perform a job, the general health condition and the kind of job (physical/mental demands).32 However, influences from different structures of the social insurance system, the job market situation and cultural differences in absence behaviour may also be relevant. This has also been observed in other musculoskeletal disorders.33

Our study showed much higher incapacity for work measured in absence days than in another Swiss study.7 However, in this other study the working ability of 97.3% was a point measurement, and the number of patients only working part-time due to their health condition had not been identified. These distinctions in the methods and the low return rate of questionnaires in this other study could explain the difference in the results of these studies. The correlation coefficient of r=−0.755 reveals a good correlation between the WAI and the QW. This supports the concurrent validity of the QW. The negative relationship means that having a low score in the WAI leads to more absence days.

Implications of this study

The WAI reflected the absence days in a group of AS patients with the help of a two-part regression model. In the future, absence days may be estimated by multiplying the probability of the logistic regression with the results of the linear regression. This may be useful for some aspects of economic evaluations to quantify the productivity loss.34 Age and gender did not confound the results. Usually, absence days are very time-consuming and difficult to measure because of part-time work, partial incapacity for work, partial or full invalidity pension and the potential incapability of the patients to recall all the subtle differences in their absences. Therefore, the WAI offers some advantages in contrast to questionnaires with a huge set of questions: it takes only 10 min to be completed; it reflects the subjective view of the patients and the scoring is clearly understandable.

Strengths of this study

The study showed that the use of the WAI is feasible not only in a prevention setting such as occupational healthcare but also in a clinical setting for patients with AS. We took into account that the data are skewed and checked the goodness of fit of the regression model by splitting the group into two halves, estimating the values of the other half and by correlating the true values with the estimated values. The procedure confirmed the stability of the regression model.

Weaknesses of the study

The absence days were gathered retrospectively. The precision of people's memory to report the number of absence days of the previous year is questionable,35 and therefore the absence days computed by the QW may not be accurate. Severens et al postulated that a 64% agreement between self-reported and register gathered absence days results, if a 3 day discrepancy in absence days is regarded as acceptable. The results of this study are not generalisable for other subjects than people with AS. Perhaps patients with a high motivation to influence their health were overrepresented in this study, since they were readily willing to undergo cardiovascular training. Such patients may also have been more willing to maintain their ability to work. This could lead to an underestimation of the absence days.

Since a questionnaire encompassing the complicated nature of the construct of the incapacity for work does only exist to report absence days over a very short time span, we made use of the new not validated QW. The substantial correlation between the WAI and the QW implicates an acceptable concurrent validity. The sample size is not very big to conduct a multiple-regression analysis. However, we had 11 patients per variable and this lies above the recommended number of patients (5–10 times the number of included variables).

In summary, statistical models using the WAI for estimating absence days offer an innovative and time-saving approach for studies where incapacity for work has to be measured.

Conclusions

Incapacity for work in a sample of AS patients was equal to that in pan-European countries. The WAI was feasible for use in AS patients. It validly assesses incapacity for work evaluating groups of participants suffering from AS. In the future, absence days may be calculated by computing the absence days through a regression analysis including the WAI score as a variable. Further research may evaluate whether these results are replicable in patients with other health conditions than AS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Professor Beat A. Michel for supporting the study and the publication. We also thank to Professor Heike A. Bischoff-Ferrari and Barbara Gubler-Gut from the Division of Rheumatology and Institute of Physical Medicine for providing the infrastructure within our Research Unit to carry out this study. Further thanks go to the Swiss Ankylosing Spondylitis Association for their support and to all the patients who took part in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: KM, KN and AK conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. KM and AT were responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. KN and AK provided input into the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by KM and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. KN and KM were responsible for the acquisition of the data and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Kantonale Ethikkommission, SPUK Zurich, EK 746.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Braun J, Bollow M, Remlinger G, et al. Prevalence of spondylarthropathies in HLA-B27 positive and negative blood donors. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:58–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Linden SM, Valkenburg HA, De Jong BM, et al. The risk of developing ankylosing spondylitis in HLA-B27 positive individuals. A comparison of relatives of spondylitis patients with the general population. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:241–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gran JT, Husby G, Hordvik M. Prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in males and females in a young middle-aged population of Tromsø, northern Norway. Ann Rheum Dis 1985;44:359–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boonen A, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. Work status and productivity costs due to ankylosing spondylitis: comparison of three European countries. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:429–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boonen A, de Vet H, van der Heijde D, et al. Work status and its determinants among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. A systematic literature review. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1056–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner R, Kissling RO, Auckenthaler C, et al. Clinical evaluation of ankylosing spondylitis in Switzerland. Pain Physician 2002;5:49–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellmann J, Kissling R, Baumberger H. [Socio-professional aspects of ankylosing spondylitis in Switzerland]. Z Rheumatol 1996;55:105–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quadrello T, Bevan S, McGee R. Fit for work? Erkrankungen des Bewegungsapparats und der Schweizer Arbeitsmarkt. London: The Work foundation, 2009:16 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niedhammer I, Bugel I, Goldberg M, et al. Psychosocial factors at work and sickness absence in the Gazel cohort: a prospective study. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:735–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North F, Syme SL, Feeney A, et al. Explaining socioeconomic differences in sickness absence: the Whitehall II Study. BMJ 1993;306:361–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Läubli T, Müller C. Arbeitsbedingungen und Erkrankungen des Bewegungsapparates—geschätzte Fallzahlen und Kosten für die Schweiz. Die Volkswirtschaft 2009;82:22–5 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:812–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, et al. Work ability index. Helsinki: Finnish Institute of Occupational Health ICOH, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin Why WAI?- Der Work Ability Index im Einsatz für Arbeitsfähigkeit und Prävention. Erfahrungsberichte aus der Praxis. Dortmund: Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin, 2011:8–13

- 15.Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Seitsamo J, et al. Summary of the Finnish research project (1981–1992) to promote the health and work ability of aging workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 1997;23(Suppl 1):66–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radkiewicz P, Widerszal-Bazyl M. Psychometric properties of work ability index in the light of comparative survey study. Int Congress Ser 2005;1280:304–9 [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Zwart BCH, Frings-Dresen MHW, van Duivenbooden JC. Test-retest reliability of the work ability index questionnaire. Occup Med (Lond) 2002;52:177–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh IA, Corral S, Franco RN, et al. Work ability of subjects with chronic musculoskeletal disorders. Rev Saude Publica 2004;38:149–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jedryka-Góral A, Bugajska J, Lastowiecka E, et al. Work activity and ability in aging patients suffering from chronic cardiovascular diseases. Int Congress Ser 2005;1280:190–5 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knekt P, Lindfors O, Laaksonen MA, et al. Effectiveness of short-term and long-term psychotherapy on work ability and functional capacity-a randomized clinical trial on depressive and anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord 2008;107:95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoving JL, Bartelds GM, Sluiter JK, et al. Perceived work ability, quality of life, and fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after a 6-month course of TNF inhibitors: prospective intervention study and partial economic evaluation. Scand J Rheumatol 2009;38:246–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lastowiecka E, Bugajska J, Najmiec A, et al. Occupational work and quality of life in osteoarthritis patients. Rheumatol Int 2006;27:131–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labriola M, Lund T, Burr H. Prospective study of physical and psychosocial risk factors for sickness absence. Occup Med (Lond) 2006;56:469–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, et al. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2286–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2281–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkinson TR, Mallorie PA, Whitelock HC, et al. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The bath AS metrology index. J Rheumatol 1994;21:1694–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukas C, Landewe R, Sieper J, et al. Development of an ASAS-endorsed disease activity score (ASDAS) in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:18–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schramm AB, Jastal AM, Pastuszko T. Permanent disablement for work in patients with spondylitis ankylopoetica and arthritis rheumatoidea. Scand J Rheumatol 1975;(Suppl 8): Abstract 12–02 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wordsworth BP, Mowat AG. A review of 100 patients with ankylosing spondylitis with particular reference to socio-economic effects. Br J Rheumatol 1986;25:175–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillemin F, Briancon S, Pourel J, et al. Long-term disability and prolonged sick leaves as outcome measurements in ankylosing-spondylitis—possible predictive factors. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1001–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward MM, Kuzis S. Risk factors for work disability in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol 2001;28:315–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barlow JH, Wright CC, Williams B, et al. Work disability among people with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:424–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waddell G. The biopsychosocial model. In: Waddell G. The back pain revolution. London: Churchill Livingston, 2004:265–82 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W, Bansback N, Anis AH. Measuring and valuing productivity loss due to poor health: a critical review. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:185–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Severens JL, Mulder J, Laheij RJF, et al. Precision and accuracy in measuring absence from work as a basis for calculating productivity costs in The Netherlands. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:243–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.