Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the relationship between poststroke fatigue and depression and subsequent mortality in young ischaemic stroke patients in a population-based study.

Design

A prospective cohort study.

Setting

All surviving young ischaemic stroke patients living in Hordaland County.

Participants

Young ischaemic stroke patients aged 15–50 years at the time of the stroke were invited to a follow-up on an average 6 years after the index stroke. Psychosocial factors and risk factors were registered. Fatigue was self-assessed by the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS). Depression was measured by Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

Intervention

No intervention was performed.

Primary and secondary outcome measure

Mortality on follow-up.

Results

In total, 190 patients were included. The mean age on follow-up was 48 years and subsequent follow-up period was 12 years. Cox regression analysis showed that mortality was associated with FSS score (p=0.005) after adjusting for age (p=0.06) and sex (p=0.19). Cox regression analysis showed that mortality was associated with MADRS score (p=0.006) after adjusting for age (p=0.10) and sex (p=0.11).

Conclusions

Both fatigue and depression are associated with long-term mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke. Depression may be linked to higher mortality because of psychosocial factors and unhealthy lifestyles whereas the link between fatigue and mortality is broader including connection to diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction and psychosocial factors.

Keywords: Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

We hypothesised that fatigue and depression are associated with increased mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke irrespective of stroke severity.

Key messages

On Cox regression analyses both fatigue and depression are associated with long-term mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke after adjusting for age, sex and stroke severity. Depression may be linked to higher mortality because of psychosocial factors and unhealthy lifestyles whereas the link between fatigue and mortality is broader including a connection to diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction and psychosocial factors.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths include population-based approach and long follow-up period.

Limitations include retrospective case finding and no data on cause of death.

Outcome after ischaemic stroke is better among young adults than older patients. However, several studies have reported high long-term mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke as compared to matched controls.1 Factors such as hypertension, alcoholism, coronary heart disease, severe stroke and age have been linked to mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke.1–3

The study of stroke among young people is important for several reasons. The aetiology of stroke is much more diverse and risk factors for stroke differ between young and old patients and may indicate separate approaches as to treatment. Stroke in young adults provides an opportunity to study stroke in general because of less comorbidity than in old patients. Fatigue has been recognised as a disabling symptom in non-depressed stroke patients.4 Young stroke patients need information on prognosis, including factors related to fatigue or depression, to make informed choices about vocation and employment. Among old stroke patients it has been shown that both fatigue5 and depression6 are associated with mortality. However, little is known about the effect of fatigue or depression on survival in young adults with ischaemic stroke.

We present data on the effect of fatigue and depression measured on an average 6 years after the index stroke and subsequent mortality. We hypothesised that fatigue and depression are associated with increased mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke irrespective of stroke severity.

Method

All patients 15–49 years old with first-ever cerebral infarction from 1988 to 1997 living in Hordaland County were included in a database. An upper limit of 49 years was chosen because these patients have low comorbidity compared with that among older patients and because they still have many years left in the work force. Cerebral infarction was defined in accordance with the Baltimore-Washington Cooperative Young Stroke Study Criteria comprising neurological deficits lasting more than 24 h because of ischaemic lesions or transient ischaemic attacks where CT or MRI showed infarctions related to the clinical findings.7 We excluded patients with cerebral infarction associated with other intracranial diseases such as subarachnoidal haemorrhage, sinus venous thrombosis or severe head trauma. Case-finding was performed retrospectively as described previously.8

Surviving patients were invited to a follow-up investigation in person in our out-clinic department on an average 6 years after the index stroke. On follow-up, data on employment, level of education and marital status were obtained by the authors. Risk factors including alcoholism, smoking, diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction were registered. Stroke severity was determined by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), Barthel Index (BI) and Scandinavian Stroke Scale (SSS) on follow-up. Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Fatigue was measured by the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS).9 10 FSS is a nine-item questionnaire that assesses the effect of fatigue on daily living. Each item is a statement on fatigue that the subject rates from 1, ‘completely disagree’ to 7, ‘completely agree’. Examples of the items in the questionnaire are: ‘Fatigue is among my three most disabling symptoms’, ‘Exercise brings on my fatigue’ and ‘I am easily fatigued’. The average score of the nine items represents the FSS score (the minimum score being 1 and maximum 7). Fatigue was defined as FSS score ≥5.11

Depressive symptoms were quantified using Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) at the follow-up.12 Poststroke depression (PSD) was defined as MADRS score ≥7.13 14

Subsequent survival state was registered by examining the official population registry by 1 August 2011. The study was approved by the local Ethics committee.

Statistics

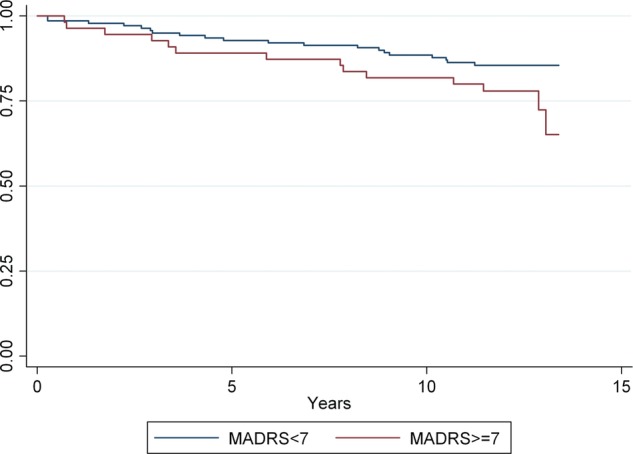

Fisher's exact test (categorical variables), Student t test (continuous variables) and pair-wise correlation test were used as appropriate. Cox regression analyses were used for disclosing variable associated with mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival curves grouped by dichotomised FSS (FSS<5 vs ≥5) and MADRS scores (MADRS<7 vs MADRS≥7) were obtained. All tests were two sided. Level of significance was set at p<0.05. STATA V.11.0 was used for analyses.

Results

A total of 232 patients had first-ever ischaemic stroke. At the time of invitation 209 patients were alive and the present study includes 190 patients: 81 (43%) female patients and 109 (57%) male patients. The mean age on follow-up was 48 years. During a subsequent mean follow-up time of 12.4 years 32 (16.8%) patients had died. (The mean total follow-up time since the index stroke was 18 years.)

Univariate analyses showed that mortality was associated with factors such as being unmarried, unemployed, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, myocardical infarction, age, mRS, SSS, BI, MMSE, FSS and MADRS scores (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of young ischaemic stroke patients according to survival or death

| Dead, n (%) | Alive, n (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 32 (17) | 158 (83) | |

| Male patients | 22 (20) | 87 (80) | 0.17 |

| Female patients | 10 (12) | 71 (88) | |

| Unmarried | 13 (27) | 36 (73) | 0.05 |

| Higher education | 8 (14) | 48 (86) | 0.67 |

| Unemployed | 22 (29) | 53 (71) | <0.001 |

| Alcoholism | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | 0.004 |

| Smoking | 17 (22) | 60 (78) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (35) | 13 (65) | 0.05 |

| Myocardial infarction | 10 (53) | 9 (47) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age on follow-up | 51.2 (6.6) | 47.2 (8.3) | 0.01 |

| mRS score | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.0) | 0.03 |

| SSS score | 54 (8.4) | 56 (4.5) | 0.08 |

| BI | 96 (13) | 99 (5) | 0.04 |

| FSS score | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.0 (1.6) | 0.003 |

| MADRS score | 7.8 (7.3) | 4.3 (5.9) | 0.004 |

| MMSE | 26.8 (3.6) | 28.2 (2.1) | 0.003 |

BI, Barthel Index; FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; SSS, Scandinavian Stroke Scale.

Cox regression analysis showed that mortality was associated with FSS (HR=1.4, CI 1.1 to 1.7, p=0.005) after adjusting for age (p=0.06) and sex (p=0.19). Including BI, mRS or SSS separately did not change these findings. Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves dichotomised for FSS<5 and ≥5.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves dichotomised for FSS<5 and FSS≥5. FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale.

Cox regression analysis showed that mortality was associated with the MADRS score (HR=1.06, CI 1.02 to 1.11, p=0.006) after adjusting for age (p=0.10) and sex (p=0.11). Including BI, mRS or SSS separately did not change these findings. Figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meier survival curves dichotomised for MADRS<7 and ≥7.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves dictotomised for MADRS<7 & MADRS≥7. MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Stepwise Cox regression analyses based on all variables in table 1 showed mortality to be associated with alcoholism (HR=5.3, p=0.001), myocardial infarction (HR=3.0, p= 0.011) and unemployment (HR=2.9, p=0.013) after adjusting for age (p=0.29) and sex (p=0.28).

Stepwise Cox regression analyses based on all variables in table 1 excluding alcoholics showed mortality to be associated with diabetes mellitus (HR=3.1, p=0.023), myocardial infarction (HR=4.1, p=0.001) and MADRS score (HR=1.08, p=0.002) after adjusting for age (p=0.32) and sex (p=0.36) (see table 2).

Table 2.

Cox regression survival analysis among non-alcoholic young adults with ischaemic stroke

| HR | CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.04 | 0.97 to 1.1 | 0.32 |

| Sex | 1.5 | 0.6 to 3.4 | 0.36 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.1 | 1.2 to 8.3 | 0.023 |

| Myocardial infarction | 4.1 | 1.8 to 9.4 | 0.001 |

| MADRS score | 1.08 | 1.03 to 1.13 | 0.002 |

MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Tables 3 and 4 show correlation analyses between MADRS and FSS scores and relevant factors. MADRS was correlated with smoking, alcoholism, being unmarried, unemployment and stroke severity (all p<0.05). FSS was correlated with diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, alcoholism, unemployment, depression and stroke severity (all p<0.05). Correlation was the highest between MADRS scores and FSS scores (r=0.60, p<0.001). There was moderately high correlation between FSS scores and unemployment (r=0.31, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and correlation analyses in young ischaemic stroke patients[colcnt=3]

| Correlation | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.05 | 0.49 |

| Female patients | 0.07 | 0.31 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.01 | 0.90 |

| Smoking | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| Alcoholism | −0.17 | 0.02 |

| Married | −0.20 | 0.007 |

| Employed | −0.31 | <0.001 |

| Higher education | −0.12 | 0.11 |

| FSS score | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| mRS score | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| MMSE | −0.08 | 0.25 |

FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Table 4.

Fatigue severity scale score and correlation analyses in young ischaemic stroke patients

| Correlation | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.05 | 0.47 |

| Female patients | 0.06 | 0.41 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.13 | 0.007 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.16 | 0.002 |

| Smoking | 0.07 | 0.36 |

| Alcoholism | −0.15 | 0.003 |

| Married | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Employed | −0.23 | 0.002 |

| Higher education | −0.11 | 0.13 |

| MADRS | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| mRS score | 0.24 | 0.001 |

| MMSE | −0.08 | 0.25 |

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Discussion

The main findings in the present study were that both fatigue and depression were associated with subsequent long-term mortality irrespective of stroke severity. Consistent with these findings other studies have disclosed that fatigue is associated with mortality in older stroke patients.15 16 Likewise others have reported depression to be associated with mortality in older stroke patients.6 17–19

It is unlikely that fatigue causes death. It is more probable that fatigue is linked to other factors that directly cause death. Consistent with this, fatigue disappeared in the stepwise Cox regression analyses including all variables associated with death on univariate analyses. We found a strong correlation between fatigue and depression. Weaker correlations were found between fatigue and mRS, unemployment, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction. Studies including older stroke patients reported poststroke fatigue to be associated with diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction.15 20 Both diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction are diseases associated with mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke.1 It seems likely that the link between fatigue and diseases such as diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction partially explains the association between fatigue and mortality in young ischaemic stroke patients. This probably also pertains to the link between fatigue and alcoholism.

As with fatigue, we found that depression was weakly linked to other factors including unemployment, being unmarried, alcoholism and mRS. However, unlike fatigue, depression was not associated with diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction. Consistent with our findings another study including older stroke patients disclosed depression on follow-up, which was found to be associated with being unmarried but not with diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction, whereas there was a correlation between fatigue and myocardial infarction and a trend towards correlation between fatigue and diabetes mellitus.6 15 It is possible that there is a more direct link between depression and mortality than between fatigue and mortality. Possible mechanisms include suicide, alcoholism and less focus on healthy lifestyle. The weak correlation between smoking and depression among our patients hints at the unhealthy lifestyle among depressed patients.

On univariate analyses, we found that depression was mostly linked to psychosocial factors whereas fatigue was linked to a wider set of factors including both psychosocial factors and specific diseases such as diabetes mellitus and myocardial infarction. Similar findings have been disclosed among older stroke patients.6 15 This shows that there is a multifactorial basis for poststroke fatigue. Careful investigations are needed to determine the cause of fatigue and target treatment both to improve general health and survival. Depression seems mostly confined to psychosocial factors. Alcoholic abuse should be considered as an unhealthy lifestyle which may need particular attention in depressed patients with ischaemic stroke.

We found age to be associated with increased mortality on univariate analysis, but this association disappeared on Cox regression analyses. Others have found increasing age to be associated with higher mortality among young ischaemic stroke patients.2 3

The strengths of this study are the population-based approach and the long-term follow-up period. A weakness is that patient finding was performed retrospectively which may have affected both case finding and case ascertainment. Another weakness is that we have no data on the cause of death or the use of antidepressive medication. Risk factor profile and stroke treatment have changed since 1988–1997, and this should be taken into account while interpreting the results.

In conclusion, both fatigue and depression are associated with long-term mortality in young adults with ischaemic stroke. Depression may be linked to higher mortality because of psychosocial factors and unhealthy lifestyles whereas the link between fatigue and mortality is broader including connection to diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction and psychosocial factors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HN and HN conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. HN was responsible for undertaking the study analyses and produced the table and the graphs. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by HN and then examined by HNy for critical revision. HN and HNy were responsible for the acquisition of the data and both contributed to the interpretation of the results. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the local ethics committee, REK Vest Norway.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Naess H, Waje-Andreassen U. Review of long-term mortality and vascular morbidity amongst young adults with cerebral infarction. Eur J Neurol 2009;17:17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varona JF, Bermejo F, Guerra JM, et al. Long-term prognosis of ischemic stroke in young adults. Study of 272 cases. J Neurol 2004;251:1507–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putaala J, Curtze S, Hiltunen S, et al. Causes of death and predictors of 5-year mortality in young adults after first-ever ischemic stroke: the Helsinki Young Stroke Registry. Stroke 2009;40:2698–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staub F, Bogousslavsky J. Fatigue after stroke: a major but neglected issue. Cerebrovasc Dis 2001;12:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naess H, Nyland HI, Thomassen L, et al. Fatigue at long-term follow-up in young adults with cerebral infarction. Cerebrovasc Dis 2005;20:245–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naess H, Lunde L, Brogger J, et al. Depression predicts unfavourable functional outcome and higher mortality in stroke patients: the Bergen stroke study. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2010;190:34–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson CJ, Kittner SJ, McCarter RJ, et al. Interrater reliability of an etiologic classification of ischemic stroke. Stroke 1995;26:46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naess H, Nyland HI, Thomassen L, et al. Incidence and short-term outcome of cerebral infarction in young adults in western Norway. Stroke 2002;33:2105–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz JE, Jandorf L, Krupp LB. The measurement of fatigue: a new instrument. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:753–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, et al. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989;46:1121–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tellez N, Rio J, Tintore M, et al. Does the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale offer a more comprehensive assessment of fatigue in MS? Mult Scler 2005;11:198–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry 1979;134:382–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pohjasvaara T, Leppavuori A, Siira I, et al. Frequency and clinical determinants of poststroke depression. Stroke 1998;29:2311–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrmann N, Black SE, Lawrence J, et al. The Sunnybrook stroke study: a prospective study of depressive symptoms and functional outcome. Stroke 1998;29:618–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naess H, Lunde L, Brogger J, et al. Fatigue among stroke patients on long-term follow-up. The Bergen stroke study. J Neurol Sci 2012;312:138–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glader EL, Stegmayr B, Asplund K. Poststroke fatigue: a 2-year follow-up study of stroke patients in Sweden. Stroke 2002;33:1327–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams LS, Ghose SS, Swindle RW. Depression and other mental health diagnoses increase mortality risk after ischemic stroke. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1090–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris PL, Robinson RG, Andrzejewski P, et al. Association of depression with 10-year poststroke mortality. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:124–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everson SA, Roberts RE, Goldberg DE, et al. Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke mortality over a 29-year period. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1133–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Surridge DH, Erdahl DL, Lawson JS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of diabetes mellitus. Br J Psychiatry 1984;145:269–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.