Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy of Food and Drug Administration recommended dosing of nicardipine versus labetalol for the management of hypertensive patients with signs and/or symptoms (S/S) suggestive of end-organ damage (EOD).

Design

Secondary analysis of the multicentre prospective, randomised CLUE trial.

Setting

13 academic emergency departments in the USA.

Participants

Eligible patients had two systolic blood pressure (SBP) measures ≥180 mm Hg at least 10 min apart, no contraindications to nicardipine or labetalol and predefined S/S suggestive of EOD on arrival.

Interventions

Medications were administered by continuous infusion (nicardipine) or repeat intravenous bolus (labetalol) for a study period of 30 min or until a specified target SBP ±20 mm Hg was achieved.

Primary outcome measure

Percentage of participants achieving a predefined target SBP range (TR) defined as an SBP within ±20 mm Hg as established by the treating physician.

Results

Of the 141 eligible patients, 49.6% received nicardipine, 51.7% were women and 81.6% were black. Mean age was 52.2±13.9 years. Median initial SBP did not differ in the nicardipine (210.5 (IQR 197–226) mm Hg) and labetalol (210 (200–226) mm Hg) groups (p=0.862). Nicardipine patients were more likely to have a history of diabetes (41.4% vs 25.7%, p=0.05) but there were no other historical, demographic or laboratory differences between groups. Within 30 min, nicardipine patients more often reached the target SBP range than those receiving labetalol (91.4% vs 76.1%, difference=15.3% (95% CI 3.5% to 27.3%); p=0.01). On multivariable modelling with adjustment for gender and clinical site, nicardipine patients were more likely to be in TR by 30 min than patients receiving labetalol (OR 3.65, 95% CI 1.31 to 10.18, C statistic=0.72).

Conclusions

In the setting of hypertension with suspected EOD, patients treated with nicardipine are more likely to reach prespecified SBP targets within 30 min than patients receiving labetalol.

Clinical Trial Registration

NCT00765648, clinicaltrials.gov

Keywords: blood pressure, hypertension, hypertensive emergency, end organ damage, nicardipine, labetalol

Article summary.

Article focus

There has been a lack of clinical trial data specific to the management of patients with acute hypertension in the emergency department (ED) and clinicians have had little evidence-based guidance as to the optimal agent for blood pressure (BP) control.

Hypertensive individuals with suspected end-organ damage (EOD) may have different treatment responses than those without.

Our objective was to compare the efficacy of nicardipine versus labetalol for the management of hypertensive patients with signs and/or symptoms (S/S) suggestive of EOD.

Key messages

Hypertensive emergencies require immediate, controlled BP reduction to avoid or limit EOD.

Hypertensive ED patients with S/S of EOD treated with nicardipine more often reached the target systolic BP range (TR) than those receiving labetalol (91.4 vs 76.1%).

Patients treated with nicardipine were 3.7 times more likely to be in the TR within 30 min than those treated with labetalol.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The definition of EOD in this study was based on S/S of potential vascular emergencies, rather than confirmed organ injury. This approach replicates the realities of contemporary emergency medicine and suggests how these agents would work when applied to similar, undifferentiated patients in the ED.

Nicardipine infusion resulted in more rapid BP control. It is possible that observed differences simply resulted from comparison of an infusion versus bolus administration. However, most ED's do not use continuous labetalol infusions, which make our results generalisable to real-world management patterns.

The medication dosing was as per the treating physician's discretion, and BP response may be impacted by the aggressiveness of the use of either drug. Reporting on physician dosing reflects every day clinical use and suggests how patients will be treated outside of a research study.

Introduction

Systemic hypertension is a common medical condition affecting over 75 million Americans and over 1 billion people worldwide.1 2 Currently, it is estimated that 1–2% of patients with hypertension will have a hypertensive emergency during their life.3 4 Defined by the presence of acute end-organ dysfunction, hypertensive emergencies are high risk, associated with in-hospital and 30-day death rates of 2–3% and 11%, respectively, and a 90-day re-admission rate of nearly 40%.5 6 Rapid recognition, evaluation and treatment of hypertensive emergencies are necessary to prevent permanent or progressive end-organ damage (EOD). Until recently, however, there has been a lack of clinical trial data specific to the management of patients with acute hypertension and clinicians have had little evidence-based guidance as to the optimal agent for BP control.

Two medications commonly used for treatment of hypertensive emergencies are nicardipine and labetalol. Nicardipine is a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved titratable intravenous dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker with dosing that is independent of body weight. It is given as an infusion with an onset of action that ranges from 5 to 15 min and an approximate clinical offset (defined as a 10 mm Hg increase in systolic blood pressure (SBP) or diastolic blood pressure after stopping infusion) of 30 min (range 15–120 min).7 Nicardipine has high arterial vascular selectivity, with strong coronary and cerebral vasodilator effect that results in increased coronary and cerebral blood flow.8 Labetalol hydrochloride is an FDA-approved intravenous antihypertensive with both selective α and non-selective β-adrenergic receptor blocking actions. Labetalol is given as a bolus injection with recommended dose escalations every 10 min until the desired blood pressure (BP) is reached. Metabolised by the liver to form an inactive glucuronide conjugate, its onset of action is 2–5 min, reaches peak effects at 5–15 min, has an elimination half-life of 5.5 h and a duration of action that can last up to 4 h.

The recently completed Comparative effectiveness trial of nicardipine versus Labetalol Use in the Emergency department (CLUE) study was a phase IV, randomised, investigation which sought to compare the efficacy and safety of a premixed intravenous nicardipine infusion versus intravenous bolus labetalol for the management of acute hypertension. CLUE demonstrated that patients treated with nicardipine are more likely to reach a physician-specified target SBP range within 30 min than those treated with labetalol.9 Since CLUE's primary objective was to determine which agent was most effective at immediate BP control, broad enrolment of hypertensive patients was allowed. Hypertensive individuals with suspected EOD, however, may have different treatment responses from those without. To address this, we performed a post hoc analysis of CLUE patients limited to those with signs and/or symptoms suggestive of EOD at the time of emergency department (ED) presentation.

Methods

This was a prespecified secondary investigation of the original CLUE study (reported elsewhere9), designed before statistical analysis was performed, but after the database was complete and locked. Briefly, CLUE was a multicentre study involving 13 USA academic EDs, each with institutional review board approval. Eligible patients had to have an SBP≥180 mm Hg on two consecutive cuff measurements 10 min apart. Patients were ineligible if they had specific contraindications to receive either a β-blocker or a calcium channel blocker or if they presented with a condition associated with an evidence-based guideline indication for a certain agent (eg, β-blockade in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction). Patients were also excluded if they met any of the following criteria: use of any investigational drug within 30 days, pregnant or breastfeeding, allergy to β-blockers and calcium channel blockers (per FDA-approved labelling for nicardipine and labetalol), known advanced aortic stenosis, acute asthma, overt cardiac failure, greater than a first-degree heart block, cardiogenic shock, severe bradycardia, obstructive airway disease, decompensated heart failure or a known left ventricular ejection fraction <35%, cerebral vascular accident (CVA) within 30 days, known liver failure, suspected myocardial infarction, suspected aortic dissection, suspected cocaine use as the cause of ED presentation, or if they were concurrently receiving any intravenous antihypertensive medication.

After enrolment but before randomisation, the treating physician was required to define a target SBP ±20 mm Hg (defined as the target range (TR)). Subjects were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either an intravenous nicardipine or bolus intravenous labetalol and the active treatment period was 30 min. Randomised patients were required to receive the first dose of the study drug as soon as possible, ideally within 30 min of enrolment. BPs were monitored via automated brachial cuff every 5 min during the first 30 min. After the study drug initiation, the use of any additional antihypertensive was discouraged during the first 30 min. Thereafter, rescue medications could be administered to achieve further reductions in BP as deemed clinically necessary. Vital signs and potential adverse events were monitored for 6 h or to ED discharge, whichever came first, after the initiation of study drug. Patient disposition (eg, clinical decision unit, hospitalisation, etc) and mortality were determined at 48 h after enrolment.

Study drug dosing followed FDA-recommended schedules. Nicardipine was started at 5 mg/h and increased every 5 min by 2.5 mg/h, until the TR or a maximum of 15 mg/h was achieved. If TR was reached sooner than 30 min, the infusion rate was decreased to 3 mg/h with subsequent adjustment to maintain the desired BP range. Labetalol was given as an initial intravenous bolus of 20 mg over 2 min, with repeat dosing at 20, 40 or 80 mg every 10 min until the TR was reached or a maximum of 300 mg had been administered.

End-organ damage

For purposes of this subanalysis, we defined EOD as the presence of one or more of the following signs or symptoms consistent with a potential hypertensive vascular emergency at presentation, prior to randomisation: chest pain, shortness of breath, epigastric discomfort, syncope, dizziness, blurred vision, diplopia, diminished level of consciousness, confusion or haematuria.

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics were presented as percentages (%) for categorical variables, means±SD for normally distributed continuous variables and medians with IQR for non-normally distributed continuous variables. All normally distributed continuous data were compared by Student t test; otherwise Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. For categorical variables, the χ2 or Fisher's exact test was used. Missing values were not imputed and only observed values were used for analyses. The proportion of patients in each arm achieving the target SBP within 30 min was compared with χ2 analysis. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess factors associated with achievement of target SBP within 30 min with forced inclusion of enrolment site as a variable in all models. Other variables with no more than 10% missing data were considered for inclusion into an adjusted model. Beginning with those variables whose univariate Wald p value was <0.1, a stepwise elimination procedure from proc logistic was used to determine the final model, which included only those variables with p<0.05. Main effect was also tested in the multivariable model to assess the treatment difference. All possible interactions with treatment were also evaluated during this process. To evaluate variability of BP control, the mean area under the curve (AUC) for time and depth of measures outside the SBP TR were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Of the 226 patients in CLUE, 141 (62.4%) met the definition for EOD preceding treatment. Two patients withdrew consent and were not included in the analysis. Of the 141 patients with defined EOD, 51.8% were women, and 82.1% were black, with a mean age of 52.2±13.9 years. Randomisation resulted in 70 patients receiving nicardipine and 71 labetalol. There were no significant differences in demographics or medical history between the nicardipine and labetalol populations except nicardipine-treated patients were more likely to have a history of diabetes and labetalol-treated patients more likely to have a history of hepatitis (table 1). The most frequent symptoms consistent with EOD included shortness of breath, chest pain, syncope/dizziness and blurred vision/diplopia (table 2). Possible EOD at presentation was associated with a history of asthma, diabetes, myocardial infarction, renal failure, hepatitis, black race and a family history of hypertension.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of patients with end-organ damage receiving either nicardipine or labetalol

| Characteristic | Nicardipine (n=70) | Labetalol (n=71) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age years±SD | 53.3±15.2 | 51.0±12.51 |

| Female | 51 | 52 |

| White | 21 | 13 |

| Black | 79 | 85 |

| Smoking history | 59 | 62 |

| Current smoker | 33 | 41 |

| Stimulant use history (cocaine or amphetamines) | 21 | 20 |

| Current stimulant use | 10 | 6 |

| Median BMI (IQR) | 29.7 (25.4, 35.0) | 29.6 (26.0, 35.3) |

| Median initial SBP (IQR) | 210.5 (197, 226) | 210 (200, 226) |

| Median initial DBP (IQR) | 115.5 (102.5, 126) | 116 (105.5, 126) |

| Median heart rate (bpm (IQR)) | 88 (76, 99) | 86 (75, 98) |

| Median respiratory rate (IQR) | 18 (16, 20) | 18 (17, 20) |

| Median pulse oximetry (%, (IQR)) | 98 (97, 100) | 99 (97, 100) |

| HX of HTN | 99 | 94 |

| Prior admission for HTN | 47 | 48 |

| HX of hyperlipidaemia | 42 | 29 |

| HX of DM | 41 | 26 |

| HX of CAD disease | 17 | 14 |

| HX of asthma | 14 | 20 |

| HX of on dialysis | 11 | 14 |

| HX of CHF | 7 | 14 |

| HX of MI | 10 | 7 |

| HX of stroke | 10 | 6 |

| HX of hepatitis | 3 | 11 |

| Median creatinine clearance (mg/dl (IQR)) | 70.5 (37.4, 99.5) | 77.3 (39.2, 104.9) |

| Median BNP (pg/dl (IQR)) | 385 (136, 3056) | 273 (141.0, 2184) |

| Troponin I (ng/ml (IQR)) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.2) |

| Abnormal ECG | 35 | 30 |

BMI, body mass index; DBP, dystolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

Overall and comparative frequencies of the signs or symptoms defined to be suggestive of end-organ damage in patients receiving either nicardipine or labetalol

| Sign/symptom of EOD (n, (%)) | Overall (n=141) | Nicardipine (n=70) | Labetalol (n=71) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shortness of breath | 61 (43.3) | 34 (48.6) | 27 (38.0) |

| Chest pain | 59 (41.8) | 33 (47.1) | 26 (36.6) |

| Syncope/dizziness | 43 (30.5) | 16 (22.9) | 27 (38.0) |

| Blurred vision/diplopia | 38 (27.0) | 19 (27.1) | 19 (26.8) |

| Epigastric discomfort | 24 (17.0) | 11 (15.7) | 13 (18.3) |

| Confusion | 8 (5.6) | 4 (5.7) | 4 (5.6) |

| Diminished level of consciousness | 6 (4.3) | 1 (1.4) | 5 (7.0) |

| Haematuria | 3 (2.1) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) |

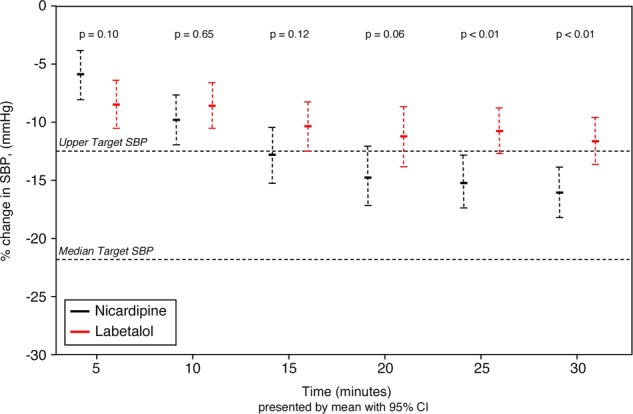

The overall initial median (IQR) SBP was 210 (199, 226) mm Hg, and did not differ between treatment groups (210.5 (IQR 197, 226) mm Hg in nicardipine patients vs 210 (IQR 200, 226) mm Hg in the labetalol group; p=0.862). The overall median (IQR) target SBP value was 170 (160, 175) mm Hg, 170 (160, 180) mm Hg for nicardipine versus 165 (155, 175) mm Hg for labetalol treated patients. Patients treated with either nicardipine or labetalol experienced relevant initial BP decreases during treatment, however, by 25 min the nicardipine and labetalol response curves had separated significantly (figure 1). Within 30 min, nicardipine patients more often reached TR than did patients treated with labetalol (91.4 vs 76.1%; difference=15.3% (95% CI 3.5 to 27.3)). To evaluate variability of BP control, the mean AUC for time and depth of measures outside the SBP TR were calculated. Although nicardipine patients had a lower median (IQR) AUC than those treated with labetalol (99.7 (8.8, 309.5) vs 143.6 (24.4, 440.1)) mm Hg/min, there were no differences in median AUC between treatment groups (p=0.320). At study completion, median (IQR) SBP for nicardipine was 163 (154, 177) vs 168 (156, 184) mm Hg in labetalol patients (difference=−5.0 mm Hg (95% CI −13.3 to 2.0)).

Figure 1.

SBP changes over time in EOD patients randomised to receive either nicardipine or labetalol. Percentage of change and 95% CI, evaluated by Student t test, relative to presenting blood pressure, during the initial 30 min, with upper level of target range and median target range indicated by horizontal dotted lines, in EOD patients who received either nicardipine or labetalol. SBP, systolic blood pressure; EOD, end-organ damage.

To further evaluate BP response, dosing patterns for nicardipine and labetalol were compared. Overall, the mean (±SD) number of titrations for nicardipine was 2.7±1.59 vs 1.4±1.0 (p<0.001) for labetalol. The median (IQR) dose of nicardipine was 3.2 (2.4, 4.8) mg, compared with 40 (40, 80) mg for labetalol (p<0.001). The dosing ranges were 1.1–6.7 mg for nicardipine, and 20–220 mg for labetalol.

Overall, the number of patients receiving rescue medications after the initial treatment period did not differ between cohorts (11.4% nicardipine vs 16.9% labetalol; difference=−5.5% (95% CI −6.0 to 16.9)). If nicardipine failed, the top three rescue antihypertensives included labetalol, hydralazine and metoprolol. If labetalol failed, the top three rescue antihypertensives included hydralazine, nicardipine and nitroglycerine.

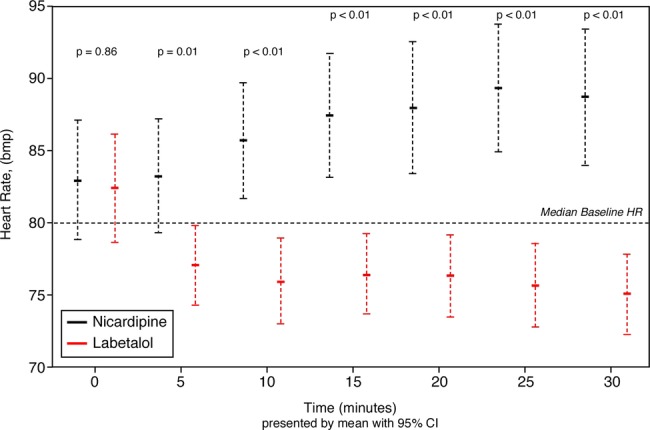

Adverse events attributed to the study drug were rare, occurring in only one nicardipine patient who developed elevated cardiac markers after admission (felt to be unlikely related to study drug) and in no labetalol patients. Labetalol patients had slower heart rates at all time points (figure 2) after treatment (p=0.012 at 5 min, p<0.01 thereafter), although none required treatment or cessation of the study drug as a consequence of bradycardia. Only two patients did not complete the study (1 labetalol and 1 nicardipine), both of which were owing to the withdrawal of consent.

Figure 2.

Heart rate changes over time in EOD patients randomised to receive either nicardipine or labetalol. EOD, end-organ damage; HR, heart rate (p value from Wilcoxon rank sum).

Lowering BP below TR (ie, overshoot) occurred in 10 (14.3%) nicardipine-treated and 7 (9.9%) labetalol-treated patients (difference=4.4% (95% CI −15.2 to 6.3)). The median (IQR) overshoot was 11.5 (9, 17) and 8 (6, 22) mm Hg for nicardipine and labetalol cohorts, respectively (difference=3.5 mm Hg (95% CI −22.2 to 11.2)). The minimum and maximum overshoot of the TR were 2 and 24 mm Hg for nicardipine and 1 and 69 mm Hg for labetalol. There were no reports of hypotension (SBP <90 mm Hg) in either group.

Multivariable modelling (table 3) showed the odds of being in the TR within 30 min for patients treated with nicardipine was more than three times than that of patients receiving labetalol (OR 3.65 (95% CI 1.31 to 10.18); p=0.02, c-statistic=0.72).

Table 3.

Final multivariable logistic model* for patients with end-organ damage

| Variable | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Nicardipine vs labetalol | 3.65 | 1.31 to 10.18 |

| Female | 3.00 | 1.12 to 8.06 |

*Outcome=met target systolic blood pressure within 30 min. Site is adjusted in the model.

To evaluate for a potential differential treatment effect in patients with versus those without EOD, interaction of treatment and EOD was also tested in the main CLUE model (adjusted for sites, gender and history of stroke). The interaction term had a p value of 0.12, which using a more relaxed threshold p value (<0.2), suggested there could be a weak treatment effect for EOD patients.

Discussion

In this analysis of patients presenting to the ED with hypertension and signs or symptoms of EOD, adjusted odds of having BP within the predefined TR within 30 min were 3.65 times greater for patients randomised to receive nicardipine. While the characteristics of nicardipine may have resulted in more rapid BP control, it is possible that observed differences simply result from comparison of an infusion with bolus administration. Method of delivery can undoubtedly lead to issues related to timing and consistency of drug administration. That labetalol doses were relatively low and titrations infrequent is thus noteworthy. There are however, many important considerations for agent selection and most institutions do not use continuous labetalol infusion routinely. Available guidelines for practice do suggest initial use of one or two bolus doses of labetalol rather than an infusion in this setting10 and our approach to study drug administration (bolus labetalol vs nicardipine infusion) likely reflects common ED practice. Accordingly, our results are generalisable to real world management patterns.

This post hoc analysis represents a unique population, separate from the overall CLUE study. CLUE allowed enrolment of all patients with elevated BP in whom the physician felt IV BP control was required. Patients with numerically high BPs, but who are otherwise asymptomatic were thus included. These patients may represent a cohort with different physiology than those with EOD. Patients with EOD would be expected to have an ongoing hypertensive stimulus, absent in the asymptomatic patient. Thus the population of patients with EOD could represent a cohort for whom obtaining BP control would be more difficult. Knowledge that rapid and sustained BP control was obtained by nicardipine in this setting suggests it would be efficacious in other cohorts requiring precise BP control.

Patients with a hypertensive emergency usually present for evaluation as a result of a new symptom related to their elevated BP4 and their initial management must proceed without a definitive diagnosis. It is only later, after the completion of a period of diagnostic testing, that EOD is confirmed. Treatment without a confirmed diagnosis is a challenge unique to emergency medicine, but critical to limit progressive end organ injury in the setting of a true hypertensive emergency. That the definition of EOD in this study was based on signs and symptoms of potential vascular emergencies, rather than confirmed organ injury may be criticised. However, this approach replicates the realities of contemporary emergency medicine and suggests how these agents would work when applied to similar, undifferentiated patients in the ED. While a symptom-based approach may result in the inclusion of some patients with ultimately negative diagnostic testing, this does allow the determination of therapeutic safety and efficacy in a cohort for whom emergency physicians are obligated to initiate antihypertensive treatment.

Of note, our definition of EOD is consistent with prior studies11–13 reporting symptoms on presentation for ED patients with hypertensive emergencies. According to Zampaglione and colleagues, the most frequent signs and symptoms associated with a hypertensive emergency are chest pain (27%), dyspnoea (22%) and neurological deficits (21%). Headache (22%), epistaxis (17%), faintness and psychomotor agitation (10%) may also be seen, though less likely to be a manifestation of acute EOD.11 As noted by Vaughan14 in a Lancet review, chest pain (myocardial ischaemia or infarction, aortic dissection), back pain (aortic dissection), dyspnoea (pulmonary oedema or congestive heart failure) and neurological symptoms (stroke), seizures, or altered consciousness (hypertensive encephalopathy) are important indicators of potential end-organ compromise and, in the setting of profoundly elevated BP, should prompt consideration of a true hypertensive emergency.

There are many parenteral agents available for treating hypertensive emergencies, yet most have specific limitations if applied to all conditions across the broad range of complex comorbidities seen in the ED patient population. An ideal agent would be readily available in the ED and easy to administer. Preferably, it should not require central venous access or invasive monitoring, and thus may differ from the ideal agent for the intensive care unit or surgical suite. Both labetalol and the nicardipine can be stored in the ED and neither typically requires invasive monitoring.

Unfortunately, there have been few ED-based comparative studies or clinical trials evaluating the optimal therapeutic agent. The only other prospective, randomised trial evaluating nicardipine versus labetalol focused on patients with acute stroke requiring BP management.15 All 25 patients who received nicardipine achieved goal BP by 24 h compared with only 15 (68%) in the labetalol group (p<0.001). Additionally, a significantly greater proportion of nicardipine-treated patients were within the goal BP by 1 h compared with those treated with labetalol (88% vs 32%; p<0.001).15 A similar retrospective, non-randomised study evaluated consecutive adults with acute stroke who received intravenous bolus labetalol or nicardipine infusion within 24 h of hospital admission.16 While no difference in overall BP response in the acute stroke patients was observed following treatment, there was significantly less variability in BP response among nicardipine-treated patients. In addition, patients who received nicardipine required lower dosage adjustments and fewer additional antihypertensive agents compared with labetalol-treated patients. As in our study, both treatments were well tolerated and no significant adverse effects were observed with either agent. Their results suggested that nicardipine was as effective and safe as labetalol for acute BP control immediately following a stroke but may be associated with easier administration.

There are several limitations of our study that need to be considered while interpreting the results. First and foremost, we note that statistical tests performed on demographic subgroups should not take priority over primary outcome measures in randomised controlled trials. Further, as discussed, the cohort for this analysis was patients with suspected but not confirmed EOD. Although this subanalysis was focused on patients with signs and symptoms consistent with EOD, we were unable to correlate these symptoms with actual EOD. Ancillary testing for EOD was carried out at the discretion of the treating physicians and, in the majority of patients, was not comprehensive. Even if such testing was completed on all patients, differentiating acute from chronic EOD would have been difficult and beyond the scope of the parent study. Additionally, the parent CLUE study excluded critically ill patients, biasing against enrolment of those with more severe manifestations of or unequivocal features caused by a true hypertensive emergency. Our data therefore, may not be representative of the BP response in patients with acute confirmed target-organ damage caused by hypertension. Of additional importance, over 80% of patients in this cohort were black. While this is comparable to the prevalence reported in the ED and ICU-based VELOCITY trial evaluating clevidipine in acute severe hypertension,17 it limits the generalisability of our findings. Importantly, however, blacks represent a population in whom hypertension is common and severe. Hypertension in blacks is often accompanied by EOD so our data are highly applicable to the population in which our results may ultimately be applied.18 Additionally, because of the comparison of an infusion to a bolus therapy, we utilised an open label design. To what extent this impacted therapeutic response cannot be determined. Another limitation relates to the actual dosing of labetalol and nicardipine. Medication dosing was per the physician's discretion, and BP response may be impacted by the aggressiveness of the use of either drug. However, reporting on physician dosing reflects real-world clinical use and suggests how patients will be treated outside of a research study. Finally, while the primary objective of the study was to determine which agent was most effective at BP control based on achieving a physician-defined target BP, it is unknown if this type of goal has a subsequent clinically important impact on morbidity, mortality or downstream healthcare resource consumption.

Conclusion

In the setting of hypertension with suspected EOD, patients treated with nicardipine are more likely to reach prespecified SBP targets within 30 min than patients receiving labetalol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A preliminary version of this paper was presented as an oral paper at the 2011 Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Annual Meeting, in Boston, MA. Its abstract appeared in the corresponding journal supplement.

Footnotes

Contributors: CMC, PL, BMB, PB, AC, DMC, DBD, BH, AH, PJ, BK, RMN, JWS and WFP were responsible for data collection and supervision of the conduct of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. AH performed the statistical analysis. CMC, PL, BMB and WFP drafted the manuscript. All authors with the exception of AH contributed to the performance of this study by enrolling patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was performed with a funding support from EKR Therapeutics, Inc. The authors retained access to data and were responsible for all decisions to publish this manuscript.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board at each of the 13 academic medical centres.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hajjar I, Kotchen T. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA 2003;290:199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez MA, Kumar SK, De Caro M. Hypertensive crisis. Cardiol Rev 2010;18:102–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggarwal M, Khan IA. Hypertensive crises: hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. Cardiol Clin 2006;24:135–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marik PE, Varon J. Hypertensive crises: challenges and management. Chest 2007;131:1949–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshmukh A, Kumar G, Kumar N, et al. Effect of Joint National Committee VII report on hospitalizations for hypertensive emergencies in the United States. Am J Card 2011;108:1277–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz JN, Gore JM, Amin A, et al. Practice patterns, outcomes, and end-organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: the studying the treatment of acute hypertension (STAT) registry. Am Heart J 2009;158:599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallin JD, Cook ME, Blanski L, et al. Intravenous nicardipine for the treatment of severe hypertension. Am J Med Sci 1988;85:331–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas CE, LeBlanc JM. Acute postoperative hypertension: a review of therapeutic options. Am J Health Syst Pharm AJHP 2004;61:1661–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peacock WF, Varon J, Baumann B, et al. CLUE: a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of IV nicardipine versus labetalol use in the emergency department. Crit Care 2011;15:R157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams H, del Zoppo G, Alberts M, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2007;38:1655–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zampaglione B, Pascale C, Marchisio M, et al. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies: prevalence and clinical presentation. Hypertension 1996;27:144–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karras DJ, Kruus LK, Cienki JJ, et al. Evaluation and treatment of patients with severely elevated blood pressure in academic emergency departments: a multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med 2006;47:230–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karras DJ, Ufberg JW, Harrigan RA, et al. Lack ofrelationship between hypertension-associated symptoms and blood pressure in hypertensive ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2005;23:106–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaughan CJ, Delanty N: Hypertensive emergencies. Lancet 2000;356:411–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu-DeRyke X, Parker D, Jr, Levy P, et al. A prospective evaluation of labetalol vs nicardipine for blood pressure management in patients with acute stroke. Crit Care Med 2009;37(Suppl):A161[Abstract No. 342]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu-Deryke X, Janisse J, Coplin WM, et al. A comparison of nicardipine and labetalol for acute hypertension management following stroke. Neurocrit Care 2008;9:167–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollack C, Varon J, Garrison N, et al. Clevidipine, an intravenous dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, is safe and effective for the treatment of patients with acute severe hypertension. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:329–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldstein C. Management of hypertensive crises. Am J Ther 2007;14:135–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.