Abstract

Objective

The clustering of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors is a serious threat for increasing medical expenses. The age-specific proportion and distribution of medical expenditure attributable to CVD risk factors, especially focused on the elderly, is thus indispensable for formulating public health policy given the extent of the ageing population in developed countries.

Design

Cost analysis using individuals’ medical expenses and their corresponding health examination measures.

Setting

Shiga prefecture, Japan, from April 2000 to March 2006.

Participants

33 213 participants aged 40 years and over.

Main outcome measures

Mean medical expenditure per year.

Methods

Gamma regression models were applied to examine how the number of CVD risk factors affects mean medical expenditure. The four CVD risk factors analysed in this study were defined as follows: hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg), hypercholesterolaemia (serum total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dl), high blood glucose (casual blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl) and smoking (current smoker). Sex-specific and age-specific investigations were carried out on the elderly (aged 65 and over) and non-elderly (aged 40–64) populations.

Results

The mean medical expenditure (per year) for the no CVD risk-factor group was only 110 000 yen at age 50 (men, 110 708 yen; women, 107 109 yen), but this expenditure was 6–7 times higher for 80-year-olds who have three or four CVD risk factors (men, 603 351 yen; women, 765 673 yen). The total overspend (excess fraction) was larger for the non-elderly (men, 15.4%; women, 11.1%) than that for the elderly (men, 0.1%; women, 5.2%) and largely driven by people with one or two CVD risk factors, except for elderly men.

Conclusions

The age-specific proportion and distribution of medical expenditure attributable to CVD risk factors showed that a high-risk approach for the elderly and a population approach for the majority are both necessary to reduce total medical expenditure in Japan.

Keywords: Cost analysis, Cardiovascular disease risk factor, Medical expenditure, Japan, Elderly population

Article summary.

Article focus

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors are often clustered in an individual which seriously increases the likelihood of suffering from CVD and this clustering of risk factors also increases medical expenses.

The present study examined age-specific and sex-specific clustering of cardiovascular risk factors, and how it affected medical expenditure in the Japanese population.

Key messages

The total overspends attributable to cardiovascular risk factors is larger among the non-elderly population in Japan.

Larger medical overspends were driven by the groups with one or two risk factors rather than by those with three or four, except for men aged 65 and over.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The statistical modelling technique which we applied was suitable for analysing skewed medical expenditure data in contrast to a previous paper.

The use of large, comprehensive community-based database of health examination and medical expenditure brought us the stratified information by sex and age.

Our focus on the elderly, which is considered to be a vulnerable and sometimes frail group, is especially important in developed countries where the proportion of the elderly is increasing.

The medical expenditure was evaluated over a relatively short time period (6 years) despite investigating long-term effects, such as stroke and myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes and smoking are well-established risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the damage caused by these factors is widespread across the developed world.1 However, it is also well-recognised in the literature that a combination of these risk factors in an individual increases the risk of CVD.2 For example, several studies have shown that the clustering of metabolic risk factors more than doubles the likelihood of CVD mortality.3 4 Moreover, from a health economics perspective, these individual CVD risk factors5–7 and their combinations8–11 have also been reported to increase total medical expenditure in developed countries. Indeed, the public health sectors in many Western nations are now facing considerable challenges because of such spiralling medical expenses.

From a financial viewpoint, the elderly population (persons aged 65 and over) is the greatest consumer of medical resources. However, even though it is clear that individual medical bills differ by age group, few studies have investigated age-specific medical expenses because of methodological issues, such as insufficient sample sizes and inappropriate statistical models. To help bridge this gap in the body of knowledge on this topic, a comprehensive community-based database for medical expenditure, which includes approximately 60 000 individuals, has been developed in Shiga, Japan. This database consists of individuals’ health examinations and their medical expenses over a 3-year to 5-year period. Exploring this database allows us to perform an age-specific cost analysis using Gamma regression models, especially for the elderly population. The present study examined the age-specific and sex-specific proportion and distribution of medical expenditure attributable to the number of CVD risk factors in the Japanese population.

Methods

Medical expenditure system in Japan

The payment of medical expenses in Japan is based on a public medical insurance institution that comprises two systems. Since 1961, all Japanese residents have been required to enrol in one of these two insurance systems under the so-called health insurance for all scheme. First, the National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme covers self-employed workers (eg, farmers, fishermen and shopkeepers), retirees and their dependents. The elderly in Japan are thus most often covered by the NHI scheme. The other insurance system (eg, Health Insurance Society and Mutual Aid Association) covers company employees and their dependents. These two systems cover 65.3% and 34.7% of the Japanese population, respectively. All charges are strictly controlled by a service-specific fee schedule set by the national government that is constant regardless of insurance system or health institution.

Study population and data

The comprehensive dataset used in this study comprised 64 450 NHI beneficiaries in Shiga prefecture in central Japan. Data on medical expenses and annual health examinations are both key components of this database. Medical expenses data were collected from the database of the Shiga Health Insurance Organization, which is a local branch of the NHI. The original database provides data from April 2000 to March 2006. For the economic evaluation, we used a mean medical expenditure (per year), which was calculated by summing-up all medical expenditure throughout the observation periods and dividing it by the total observation periods of the number of months. This monthly measure is multiplied by 12 to transform a mean medical expenditure (per year). The data of an annual health examination were provided by every local municipality of Shiga prefecture. In Japan, an annual health examination is free of charge or is inexpensive for all Japanese, entitled by the law (Act on Assurance of Medical Care for Elderly People). These data were appropriately stored with security protections in every local municipality. Data on annual health examinations from April 2000, which included the baseline information for our study, were from all 26 local municipalities in the Shiga prefecture. Both medical expenses and health examination measures were merged into the database using individual identification information (ie, name, sex and date of birth) for the administrative use. This merging process was conducted by the Shiga Health Insurance Organization, the public agency for paying insurance in Shiga. The anonymous dataset were extracted from the database and then, participants who displayed signs of blood pressure, serum total cholesterol, casual blood glucose and smoking habits (see next subsection) were included in the analysis. The participants who had not been censored during the entire follow-up period were included in the analysis (n=33 213). Medical research ethics committee approval was granted by the Shiga University of Health Science Research Ethics Committee (17-20-1).

Statistical analysis

Specifically, the four CVD risk factors analysed in this study were defined as follows: hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg), hypercholesterolaemia (serum total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dl), high blood glucose (casual blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl) and smoking (current smoker). All participants were classified into four categories (ie, none, one, two and three or four) based on the four CVD risk factors. The unit of medical expenditure was set as Japanese yen (ie, 100 Japanese yen (JPY)=0.81 pounds (GBP), at the exchange rates published on 10 August 2012).

A gamma regression model, which is a member of generalised linear models,12 was used to estimate the mean medical expenditure of the a forementioned four categories after adjusting for confounding factors. As medical expenditure data usually involve a certain proportion of zeros and some extreme values, their distribution was skewed to the right.13–15 Gamma regression is the best modelling approach to deal with this skewness.

Statistical models were formulated by sex and age. Specifically, we estimated age-specific medical expenditure (per year) for the following four ages: 50, 60, 70 and 80 years. These estimated expenses were then plotted against the number of CVD risk factors. The regional variation of local municipalities in the Shiga prefecture was considered using the generalised estimating equation approach,12 which accounts for any correlation within each municipality.

To describe how the increasing number of CVD risk factors affects total medical expenditure in Japan, age-adjusted mean medical expenditure and the corresponding number of participants were also graphed, both for the elderly (aged 65 and over) and for the non-elderly (aged 40–64) populations. The cost ratios and overspend (excess fraction) were also calculated for each CVD risk factor group. The cost ratio represents the estimated mean medical expenditure of the corresponding group divided by the reference (ie, the no CVD risk factor group), while overspend was calculated as the proportion of a certain group's excess medical expenditure relative to the whole population. This overspend can be interpreted as the medical expenditure that would not have occurred if the participants had no CVD risk factors. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS release 9.20 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

OTable 1 compares the baseline characteristics of the four CVD risk factor groups. As the number of CVD risk factors increases, the means of systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and blood glucose and the proportion of current smokers grow in both men and women. The most prevalent CVD risk factors in the study participants are hypertension in both men and women followed by smoking in men and cholesterol in women.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants, Shiga prefectural follow-up study on health examination and medical expenditure, 2000–2006

| Number of cardiovascular risk factors* |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 or 4 |

|||||||||

| Men: 4187; women: 9924 | Men: 5947; women: 8953 | Men: 1945; women: 1964 | Men: 206; women: 87 |

|||||||||

| Mean | SD | Percentage† | Mean | SD | Percentage† | Mean | SD | Percentage† | Mean | SD | Percentage† | |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| Age | 70 | 10 | – | 68 | 11 | – | 67 | 10 | – | 65 | 10 | – |

| Systolic blood pressure | 124 | 11 | 0 | 138 | 19 | 55 | 148 | 17 | 87 | 151 | 15 | 96 |

| Total cholesterol | 188 | 27 | 0 | 191 | 31 | 5 | 202 | 41 | 23 | 234 | 39 | 68 |

| Blood glucose | 103 | 23 | 0 | 106 | 29 | 1 | 118 | 50 | 8 | 178 | 94 | 45 |

| Current smokers | – | – | 0 | – | – | 38 | – | – | 82 | – | – | 94 |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| Age | 66 | 11 | – | 69 | 10 | – | 68 | 9 | – | 66 | 9 | – |

| Systolic blood pressure | 122 | 12 | 0 | 143 | 18 | 70 | 150 | 15 | 93 | 156 | 15 | 100 |

| Total cholesterol | 200 | 24 | 0 | 214 | 34 | 23 | 249 | 32 | 82 | 261 | 23 | 94 |

| Blood glucose | 98 | 19 | 0 | 102 | 27 | 1 | 112 | 46 | 7 | 168 | 92 | 39 |

| Current smokers | – | – | 0 | – | – | 6 | – | – | 18 | – | – | 70 |

*The four cardiovascular disease risk factors analysed in this study were defined as follows: hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg), hypercholesterolaemia (total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dl), high blood glucose (casual blood glucose ≥200 mg/dl) and smoking (current smoker).

†For each cardiovascular disease risk factor, the proportions (%) of participants who possess this risk factor are shown in each category.

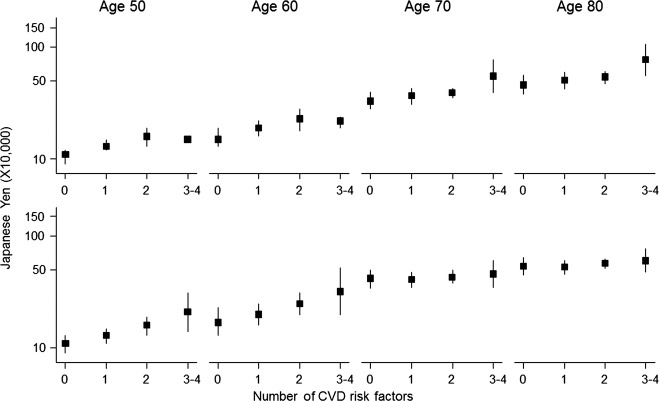

Figure 1 shows the age-specific estimated mean medical expenditure (per year) for each CVD risk factor group by sex and age. Most age group graphs indicate a gradual increase in medical expenditure as the number of CVD risk factors rises for both men and women. This figure shows that the mean medical expenditure (per year) for the no CVD risk factor group is just 110 000 yen at age 50 (men, 110 708 yen; women, 107 109 yen), but that this expenditure is 6–7 times higher for 80-year-olds who have three or four CVD risk factors (men, 603 351 yen; women, 765 673 yen).

Figure 1.

The age-specific and sex-specific estimated mean medical expenditure (per year) by cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factor group. The Gamma regression was used to estimate the mean medical expenditure in the model. The black rectangles show the mean medical expenditure (per year) of each CVD risk factor group and the corresponding solid lines show their 95% CI.

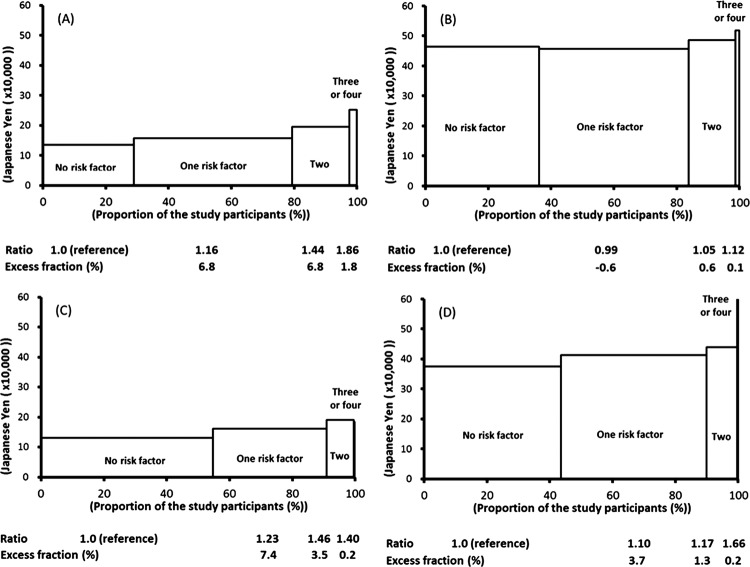

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the number of CVD risk factors and their corresponding mean medical expenditure (per year) for the four subgroups (ie, non-elderly men, elderly men, non-elderly women and elderly women) adjusted by age. The corresponding cost ratios and overspends (excess fractions) in each group are also shown by sex and age. The adjusted mean medical expenditure increases as the number of CVD risk factors rises, meaning that the cost ratio for the group with three or four CVD risk factors increases by more than 40% relative to the reference group. These trends were most obvious in non-elderly men (cost ratio 1.86). The total overspend was larger in the non-elderly population (men, 15.4%; women, 11.1%) than it was in the elderly (men, 0.1%; women, 5.2%). The total overspend was mostly driven by the groups with one (non-elderly men, 6.8%; non-elderly women, 7.4%; elderly women, 3.7%) or two risk factors (non-elderly men, 6.8%; non-elderly women, 3.5%; elderly women, 1.3%) compared with three or four risk factors (non-elderly men, 1.8%; non-elderly women, 0.2%; elderly women, 0.2%), with the exception of elderly men.

Figure 2.

The distribution of the number of cardiovascular disease risk factors, their estimated mean medical expenditure (per year) and overspending by the population: (A) men aged 40–64, (B) men aged 65 and over, (C) women aged 40–64 and (D) women aged 65 and over. Gamma regression was used to estimate the mean medical expenditure in the model. The overspend is the difference between the expenditure of each category and the reference (ie, the no cardiovascular disease risk factor group). This was defined as the proportion of excess expenditure relative to total medical expenditure.

Discussion

We performed a community-based cost analysis to investigate the sex-specific and age-specific effects of CVD risk-factor clustering on total medical expenditure in Japan. We measured the relative increase (cost ratios) and population impacts (overspends) and found that annual medical expenditure increases as the number of CVD risk factors rises in across age and sex groups. While the relative increase in the group with three or four CVD risk factors was highest, the population impacts on total medical expenditure were larger among the group with one or two CVD risk factors.

The findings from the Framingham study have already shown that Medicare costs increase with combinations of risk factors, such as hypertension, smoking and hypercholesterolaemia.8 Studies from the USA9 and Japan10 11 have also shown similar increasing patterns in the community setting. Our study showed that the cost ratios in the three or four CVD risk factor groups were between 1.44 and 1.74, which are similar to the values found in the Framingham study8 and another study in Japan.10 However, other studies have found relatively larger ratios, such as 1.84–2.45 in the USA9 and 1.91 in Japan,11 since medical expenditure is largely affected by the insurance system, study participants and the region. The different characteristics of these previous studies, such as the definition of risk factors, length of study periods and estimation procedures (statistical models), also affect their results.

The strength of our study is that the statistical modelling technique applied was suitable for analysing skewed medical expenditure data in contrast to a previous paper. The guideline from the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcome Research (ISPOR) recommended using this statistical model in the cost data analysis.13 The cost data often show a skewed distribution, which violated the equidispersion property of mean and variance. In a case with a certain proportion of zeros, a Gamma regression is the most suitable statistical model, which assumed the extra-variation (overdispersion) of the outcome. We applied a Gamma regression model12–15 for the cost analysis16 to investigate in-depth sex-specific and age-specific attributes, which is difficult in a stratified analysis. Our focus on the elderly is especially important in developed countries, where the ageing population is increasing the proportion of the elderly, which is considered to be a vulnerable and sometimes frail group.

It is important to note that individual medical expenses were highest in the three or four CVD risk factor groups for all subgroups. This population would thus be the main target for high-risk approaches to contain medical expenditure growth. High-risk strategies, such as comprehensive health guidance by public health nurses, dieticians or physicians, can be readily understood and they can strongly motivate people to change their lifestyles to manage CVD risk factors.

However, from the viewpoint of total medical expenditure, people with one or two CVD risk factors are not negligible. This population had a greater influence on total medical expenditure than did the high-CVD risk factor group, especially in the non-elderly, which accounted for more than 10% of total medical expenditure when the one or two CVD risk factor groups were combined compared with 5.0% for elderly women and 0.0% for elderly men. However, it is difficult to implement effective high-risk strategies because of the large population of people with one or two CVD risk factors. For this group, a population strategy may be useful for gradually lowering the distribution of CVD risk factors.17

The present study has several limitations. First, details of medical diagnoses, medical treatment status (eg, prescriptions), clinical conditions such as CVD history and cause of death were unavailable in this study. It is true that the medical treatment status and the clinical conditions are key elements of the increasing medical expenditure. Our reference group contained both the non-prescribed (healthy population) and the prescribed. This might overestimate the ‘referent’ mean medical expenditure. From this viewpoint, the relative measures (cost ratios) of CVD risk factors might be underestimated in this study. Second, medical expenditure was evaluated over a relatively short time period (6 years) despite investigating long-term effects. As severe health events such as stroke and myocardial infarction can occur after a long interval in high-risk individuals, excess medical expenditure might be underestimated. Third, data on fasting blood glucose, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were unavailable. Finally, because the public medical insurance system in Japan is different from those in other developed countries, we should be cautious when comparing the absolute values of medical expenses for participants in the present study.

In conclusion, this investigation into the sex-specific and age-specific effects of CVD risk factors on medical expenditure in Japan showed a large relative increase in people with three or four CVD risk factors. However, the population impacts on total medical expenditure were larger among people with one or two CVD risk factors, especially in non-elderly women. A high-risk approach for people with three or four CVD risk factors and a population approach for the majority are thus both necessary to reduce total medical expenditure in Japan.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YM, TO and KN conceived the idea of the study and were responsible for the design of the study. YM was responsible for undertaking the data analysis and produced the tables and graphs. YM, TO, KN, KM and HU provided their inputs for the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by YM and TO and then circulated among all authors for critical revisions. TO and YM were responsible for the acquisition of the data and YM, TO, KN, KM and HU contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (22590585) and Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants, Japan (Research on Health Services: H17-Kenkou-007; Comprehensive Research on Cardiovascular and Life-Style Related Diseases: H18-Junkankitou (Seishuu)-Ippan-012; Comprehensive Research on Cardiovascular and Life-Style Related Diseases: H20-Junkankitou (Seishuu)-Ippan-013; Comprehensive Research on Life-Style Related Diseases including Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus: H20-Junkankitou (Seishuu)-Ippan-013 and Comprehensive Research on Life-Style Related Diseases including Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus: H23-Junkankitou (Seishuu)-Ippan-005).

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Medical research ethics committee approval was granted by the Shiga University of Health Science Research Ethics Committee (17-20-1).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Hoorn SV, Rodgers A, et al. Estimates of global and regional potential health gains from reducing multiple major risk factors. Lancet 2003;362:271–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2003;290:891–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadota A, Hozawa A, Okamura T, et al. Relationship between metabolic risk factor clustering and cardiovascular mortality stratified by high blood glucose and obesity: NIPPON DATA90, 1990–2000. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1533–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNeill AM, Rosamond WD, Girman CJ, et al. The metabolic syndrome and 11-year risk of incident cardiovascular disease in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes Care 2005;28:385–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura K, Okamura T, Kanda H, et al. Medical costs of patients with hypertension and/or diabetes: a 10-year follow-up study of national health insurance in Shiga, Japan. J Hypertens 2006;24:2305–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izumi Y, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T, et al. Impact of smoking habit on medical care use and its costs: a prospective observation of National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30: 616–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Yan LL, et al. Relation of body mass index in young adulthood and middle age to Medicare expenditures in older age. JAMA 2004;292:2743–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schauffler HH, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB. Risk for cardiovascular disease in the elderly and associated medicare costs: the Framingham study. Am J Prev Med 1993;9:146–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Greenland P, et al. Benefit of a favorable cardiovascular risk-factor profile in middle age with respect to Medicare costs. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1122–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamura T, Nakamura K, Kanda H, et al. Effect of combined cardiovascular risk factors on individual and population medical expenditures—a 10-year cohort study of national health insurance in a Japanese population. Circ J 2007;71:807–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohmori-Matsuda K, Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, et al. The joint impact of cardiovascular risk factors upon medical costs. Prev Med 2007;44:349–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. 2nd edn NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, et al. Good research practices for cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials: the ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force report. Value Health 2005;8:521–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basu A, Manning WG. Issues for the next generation of health care cost analyses. Med Care 2009;7(Suppl 1):S109–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ 2005;24:465–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad SS, et al. Economic evaluation in clinical trials. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol 1985;14:32–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.