Abstract

Objectives

To examine the feasibility and potential benefits of early peer support to improve the health and quality of life of individuals with early inflammatory arthritis (EIA).

Design

Feasibility study using the 2008 Medical Research Council framework as a theoretical basis. A literature review, environmental scan, and interviews with patients, families and healthcare providers guided the development of peer mentor training sessions and a peer-to-peer mentoring programme. Peer mentors were trained and paired with a mentee to receive (face-to-face or telephone) support over 12 weeks.

Setting

Two academic teaching hospitals in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Participants

Nine pairs consisting of one peer mentor and one mentee were matched based on factors such as age and work status.

Primary outcome measure

Mentee outcomes of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)/biological treatment use, self-efficacy, self-management, health-related quality of life, anxiety, coping efficacy, social support and disease activity were measured using validated tools. Descriptive statistics and effect sizes were calculated to determine clinically important (>0.3) changes. Peer mentor self-efficacy was assessed using a self-efficacy scale. Interviews conducted with participants examined acceptability and feasibility of procedures and outcome measures, as well as perspectives on the value of peer support for individuals with EIA. Themes were identified through constant comparison.

Results

Mentees experienced improvements in the overall arthritis impact on life, coping efficacy and social support (effect size >0.3). Mentees also perceived emotional, informational, appraisal and instrumental support. Mentors also reported benefits and learnt from mentees’ fortitude and self-management skills. The training was well received by mentors. Their self-efficacy increased significantly after training completion. Participants’ experience of peer support was informed by the unique relationship with their peer. All participants were unequivocal about the need for peer support for individuals with EIA.

Conclusions

The intervention was well received. Training, peer support programme and outcome measures were demonstrated to be feasible with modifications. Early peer support may augment current rheumatological care.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Arthritis, Early Inflammatory Arthritis, Health Services Research, Rheumatoid Arthritis

Article summary.

Article focus

Feasibility study for developing, implementing and evaluating a peer support intervention (peer mentor training peer mentoring programme consisting of 12 weeks of face-to-face or telephone meetings to support mentees newly diagnosed with early inflammatory arthritis (EIA)).

Key messages

Early peer support is feasible and well received by both mentors and mentees.

Individuals with EIA may benefit from peer support, and this may augment current rheumatological care.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study was guided by the 2008 Medical Research Council Framework for Complex Interventions.

The intervention was well received and had benefits for both mentors and mentees.

As rheumatoid arthritis was the diagnosis of all participants, further study is needed to assess the benefit of early peer support for other types of inflammatory arthritis.

Introduction

Inflammatory arthritis (IA) is a leading cause of functional disability, chronic pain and psychosocial distress.1 2 Patient self-management, education and social support networks are encouraged as part of a holistic approach to disease management.3 A peer-to-peer mentoring programme that aims to provide support based on the sharing of information and experiences4 may benefit individuals with early inflammatory arthritis (EIA).

Individuals with EIA often reveal a complex and frustrating journey preceding diagnosis. Symptom fluctuations, symptom normalisation and dismissal of their symptoms by healthcare providers (HCPs) are factors contributing to misdiagnosis, delays in referral to rheumatology and psychological distress and frustration.1 Patients’ initial reactions to being diagnosed with EIA range from relief and acceptance to anger, fear, denial and disbelief.1 Once diagnosed, patients face an overwhelming range of biological, psychological and social issues such as disease course and severity (both of which are often unpredictable), their ability to cope with pain, as well as uncertainties about social and work issues.5 Like other chronic diseases, responsibilities for daily management gradually shift from HCPs to patients.2 Adapting to EIA is complex,6 and patients require support and guidance early in the disease process so they may learn to live and self-manage their symptoms.2 Patient education and self-management is an arthritis ‘best practice’ and a key clinical practice guideline.7–9 Peer support is one strategy to increase patients’ knowledge and skills for self-management.

Peer support models have been successfully implemented in other chronic health issues such as cancer,10 HIV/AIDS11 and diabetes.12 A peer is someone who shares common characteristics (eg, age, sex and disease status) with the individual of interest, such that the peer can relate to and empathise with the individual on a level that a non-peer would be unable to.4 Dennis defines peer support as ‘… the provision of emotional, appraisal, and informational assistance by a created social network member who possesses experiential knowledge of a specific behaviour or stressor and has similar characteristics as the target population’.13 Emotional support includes expressions of caring, empathy, encouragement and reassurance, and is generally seen to enhance self-esteem. Appraisal support involves encouraging persistence and optimism for resolving problems, affirmation of a peer's feelings and behaviours and reassurance that frustrations can be handled. Informational support involves providing advice, suggestions, alternative actions, feedback and factual information.13 All three forms of support are based on experiential knowledge, rather than formal training.13 Peer support interventions fit within a social support model.14 Within this model, peer support could reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness, provide information about accessing available health services and promote behaviours that positively improve personal health, well-being and health practices.14

Currently, the major support programme that patients with EIA can access is the Arthritis Self-Management Program.15 While it provides emotional and appraisal support, the standardised outline is not personalisable and the group format limits one-on-one interactions.

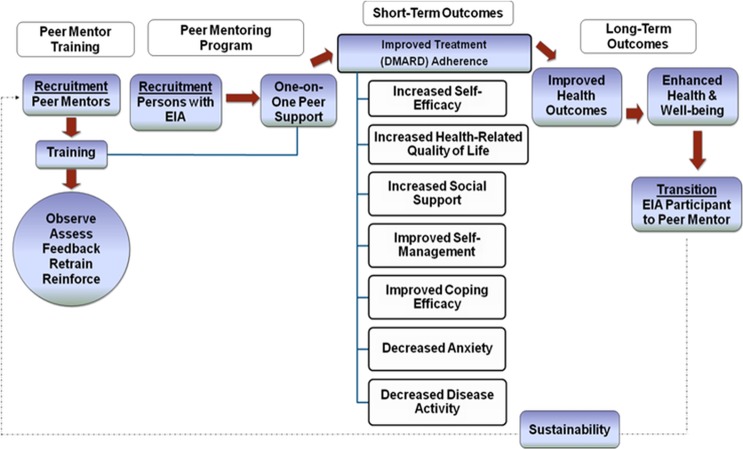

We propose that a peer support programme with trained mentors with established IA will assist those with EIA to navigate the diverse set of issues and challenges inherent in EIA, and help them self-manage their disease. An earlier study exploring the learning and support needs of patients with IA provides a rationale for using peer support,1 and previous studies have shown that individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) appear to benefit from relationships they can rely on for emotional support, information and tangible assistance.16 Whether a peer support programme may facilitate some of these benefits in patients with EIA has yet to be explored. This study examines the: (1) development and (2) feasibility and pilot phases of a peer support intervention using the 2008 Medical Research Council (MRC) Framework for the Development and Evaluation of Randomised Control Trials for Complex Interventions to Improve Health.17 The primary objective is to develop a peer mentor training process and establish the feasibility and acceptability of a peer support programme. Secondary objectives include measuring changes in various outcomes as a result of this intervention (figure 1). The development phase of the study has been described elsewhere.18 This paper reports on the feasibility and acceptability of the peer support programme and on the secondary outcome measures.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the peer support intervention programme design.

Methods

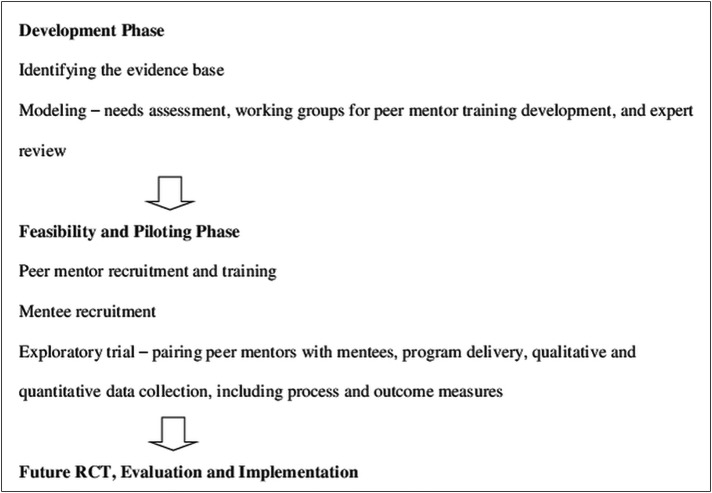

The four phases of the 2008 MRC framework guided this complex intervention:17 development phase—to establish theoretical underpinnings and modelling to achieve an understanding of the intervention and its possible effects; feasibility and piloting phase—an exploratory trial to test the feasibility of key intervention components; evaluation phase—to assess programme effectiveness and implementation phase—to examine long-term implementation and sustainability (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart outlining steps in the Medical Research Council framework.

Development phase

Identifying the evidence base

A qualitative literature search strategy was developed on peer support and chronic diseases using MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane Systematic Reviews. Reviewers independently evaluated papers using a quality assessment tool. Using metaethnography, a methodology to synthesise the qualitative literature,19 20 we determined how studies were related, translated studies into one another, synthesised translations and expressed the synthesised ethnography.18 Quantitative studies were reviewed, including a draft from a Cochrane Collaboration protocol.4 An environmental scan was performed and the grey literature summarised.

Modelling

Needs assessment

A qualitative needs assessment was performed to identify educational preferences and the informational, emotional and appraisal support needs of individuals with IA, and to determine the suitability of peer support.1 Semistructured, one-on-one interviews were performed with patients with IA, their family/friends and HCPs. Interview audio files, transcripts and field notes were uploaded to a qualitative software package, NVivo 8, for coding and analysis. Themes were identified through constant comparative analysis.21

Working groups for intervention development

Three working groups (peer mentor training, peer support programme, evaluation) of four to six research team and end users were convened to develop the pilot intervention.

Expert review

Using snowball recruiting, expert reviewers were nominated by the research team. They reviewed study information and completed a semistructured questionnaire by email about the proposed training.

Box 1. Inclusion criteria for peer mentors and mentees.

Peer mentors

Diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis (IA) from a physician

≥18 years of age

Disease duration ≥2 years

Currently using medications (DMARDS/biologics) for treatment

Completion of the Arthritis Self-Management Program (ASMP) provided by The Arthritis Society and/or similar programme

Able to attend scheduled training sessions

Able to take part in ongoing assessment/evaluation activities (self-reported questionnaires; interviews, observation; activity logs)

Able to commit for duration of study (9–12 months)

Willing to provide ongoing one-on-one support to an individual with newly diagnosed IA

Able to speak, understand, read and write English

Mentees

EIA disease duration 6–52 weeks

At least three swollen joints, assessed by the treating rheumatologist, OR

Positive compression test for metacarpophalangeal joints, OR

-

Positive compression test for metatarsophalangeal joints, OR

At least 30 min of morning stiffness

Prescribed a DMARD/biological by a rheumatologist

Able to speak, understand, read and write English without the aid of a support person

Able to provide informed consent

Peer mentors attended four training sessions (18 h total). Training provided information on EIA, educational/support resources and opportunities to learn and practice peer support techniques (informational, emotional, appraisal support) and skills (communication, decision-making, goal-setting). Mentors received two initial training sessions and an additional session based on feedback from researchers and participants. Peer mentors received a resource binder with information on arthritis and mentoring resources and ongoing support from the research team via email, telephone and in-person.

Peer mentor recruitment and training

Potential mentors were recruited from the Greater Toronto Area through the principal investigators clinic, word-of-mouth, peer mentors and e-mails from the Arthritis Society. Mentors were selected based on inclusion criteria (box 1). Eligibility screening occurred by telephone followed by face-to-face interviews.

Mentee recruitment

Patients with EIA were recruited from rheumatology clinics in two Toronto teaching hospitals, based on inclusion criteria (box 1).

Exploratory trial

Pairing and delivery

Mentees were paired with peer mentors based on age and work status. The initial meeting was face-to-face, with subsequent meetings taking place at the discretion of the pair (in-person or telephone). Dyads met weekly for approximately 12 weeks. Participants were brought together at the end for debriefing and celebrating.

Quantitative data collection

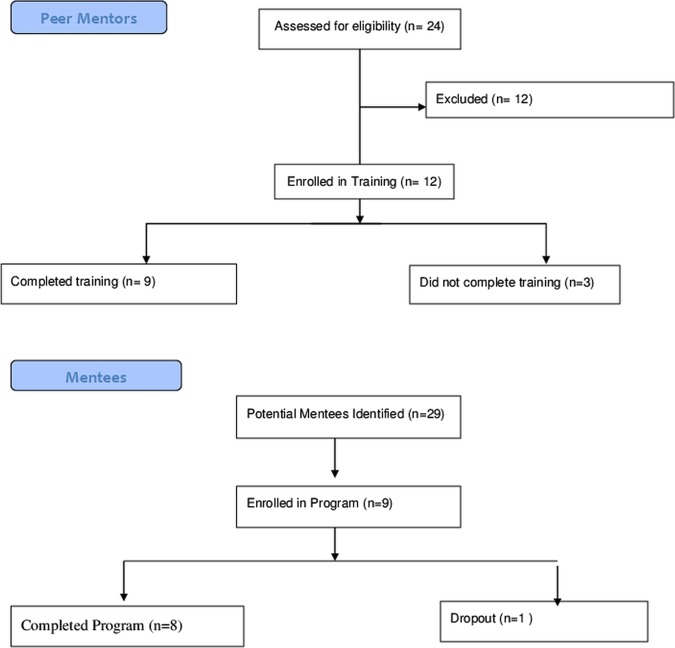

Twenty-four potential mentors were identified, of whom 12 were eligible and 9 completed the training.

Twenty-nine potential EIA participants were identified, of whom nine were enrolled and eight completed the programme (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flow diagram for peer mentor and mentee recruitment.

A before-and-after design was used to determine changes over time that can be attributed to the intervention. Peer mentors’ self-efficacy was assessed via a self-administered questionnaire at four time points—baseline (T1), post-training (T2), immediately after programme completion (T3) and 3 months postprogramme (T4). Mentee outcome data were collected by self-administered questionnaires and clinical assessment at baseline (T1), immediately after programme completion (T2) and 3 months postprogramme (T3). Outcomes are below:

Adherence to DMARD/biological treatment in EIA patients, determined indirectly through the Morisky scale.22

Self-efficacy measured by Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-Item Scale.23 24

Change in health-related quality of life and anxiety measured by Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales, second edition (AIMS2) and dimension subscore for anxiety, respectively.25

Coping-efficacy assessed by Gignac et al's method

Clinical disease activity assessed by a rheumatologist from the research team using Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score.27

Social support measured by Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOSSS).28

Self-management examined by Patient Activation Measure.29

Descriptive statistics and effect sizes were calculated to determine clinically important (>0.3) changes. Effect size, a unitless measurement of treatment effect, was used to measure the effects of the intervention. An effect size of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate and 0.8 large.30

Qualitative data and process measures

Peer mentors completed a training evaluation questionnaire. Implementation process data were collected to assess acceptability and feasibility. The number and nature of meetings, topics discussed and problems arising were recorded by peer mentors via activity log. Research staff called mentors weekly for updates. One-on-one interviews with participants were conducted to determine the acceptability and feasibility of procedures and outcome measures, and to gain perspectives on the value of peer support. Key themes were identified from transcribed data through constant comparison. Mentees’ experiences were explored using a participant diary at three time points.

Ethics approval was obtained from research ethics boards at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada. The study was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (Identification numbers: NCT01054963, NCT01054131).

Results

Development phase

Identifying the evidence base

In total, 21 489 abstracts across six chronic diseases were identified. Twenty-five articles were included in the metaethnography. Results are reported elsewhere.18

Key themes identified about peer mentor training were: setting boundaries around peer mentor roles, ensuring confidentiality, enhancing communication skills, providing continuing education and support for mentors and sharing personal experiences to aid in decision-making. Literature about the delivery of peer support programmes highlighted the importance of peer mentor recruitment, selection/assessment, outcome measures and mentee recruitment.

Modelling

Needs assessment

Peer support was a well-received approach for helping individuals with EIA to cope with concerns arising from their diagnosis. Participants perceived that peer mentoring, if context-driven (paying attention to specific disease phases and individual circumstances) and sensitive to their needs, could be valuable in managing their disease. Results are reported elsewhere.1

Working groups for intervention development

Each of the working groups met multiple times. Additional members with specific expertise were added as needed to finalise the intervention.

Expert review

Eighteen experts (individuals with IA, HCPs, peer support researchers, representatives of arthritis organisations and educators) provided input into the format/content of the peer mentor training.

Feasibility and piloting phase

Peer mentor recruitment and training

Twenty-four potential mentors were identified. Twelve were recruited. Nine completed the training and became peer mentors. Three withdrew due to personal illness and/or family issues. All mentors had RA (see table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics: peer mentors, mentees and peer mentors who withdrew

| Peer mentors (N=9) | N |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 31–40 | 1 |

| 41–50 | 2 |

| 51–60 | 3 |

| 61–70 | 3 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 9 |

| Male | 0 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 1 |

| <18 | |

| 18–30 | 3 |

| 31–40 | 3 |

| 41–50 | 0 |

| 51–60 | 1 |

| 61–70 | 1 |

| Work status | |

| Working for pay | 5 |

| Not working/homemaker | 2 |

| Retired | 2 |

| Mentees (N=9) | N |

| Age (years) | |

| 18–30 | 2 |

| 31–50 | 2 |

| 51–60 | 3 |

| 61–70 | 2 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 7 |

| Male | 2 |

| Marital status | |

| Single/never married | 1 |

| Married | 4 |

| Common law/living with someone | 3 |

| Widowed | 1 |

| Living arrangements | |

| Living alone in house or apartment | 2 |

| Living with family or friends in house or apartment | 7 |

| Work status | |

| Working for pay | 6 |

| Not working/homemaker | 2 |

| Retired | 1 |

| Highest level of education | |

| Some/completed high school | 1 |

| Some/completed college/university | 6 |

| Some/completed postgraduation | 2 |

| Peer mentors who withdrew (N=3) | N |

| Age (years) | |

| 41–50 | 2 |

| 51–60 | 1 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |

| <18 | 1 |

| 18–30 | 1 |

| 41–50 | 1 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 3 |

| Male | 0 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1 |

| Work | |

| Working for pay | 3 |

Mentee recruitment

Twenty-nine potential mentees were identified, nine of whom were eligible and enrolled. One mentee was lost to follow-up. All nine mentees had RA (see table 1).

Exploratory trial

Pairing and delivery

Nine mentor–mentee pairs participated. All mentors were women, resulting in two mixed-gender dyads.

Quantitative data collection

Mentors’ reported self-efficacy increased significantly after training completion. However, these measures dropped below baseline upon programme completion with recovery to basline levels at 3 months postprogramme (table 2).

Table 2.

Peer mentor and mentee results

| Peer mentor-reported self-efficacy | N | Mean | SD | p Value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer mentor self-efficacy scale ratings | |||||

| Baseline (T1) | 9 | 7.91 | 1.18 | ||

| Post-training (T2) | 9 | 9.14 | 0.56 | 0.01* | 1.04 |

| End of programme (T3) | 9 | 7.55 | 0.97 | 0.26 | −0.31 |

| 3 months after programme completion (T4) | 9 | 7.88 | 0.59 | 0.86 | −0.03 |

| Mentees’ mean outcome scores at baseline (T1) and programme completion (T2) | |||||

| Measurement | N | T1 | T2 | T1–T2 (SD) | Effect size T1–T2 (mean) |

| Medication adherence (Morisky scale) | 8 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0 |

| Self-efficacy scale | 8 | 7.59 | 7.75 | 1.01 | 0.04 |

| Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS2)—Short Form (SF) | |||||

| ▸ AIMS2-SF | 5 | 30.26 | 28.96 | 1.33 | 0.39 |

| ▸ AIMS2-Physical (/10) | 8 | 8.36 | 8.60 | 1.98 | 0.19 |

| ▸ AIMS2-Symptoms (/10) | 8 | 2.59 | 1.56 | 2.23 | 0.28 |

| ▸ AIMS2-Affect (/10) | 8 | 5.56 | 5.31 | 1.03 | 0.27 |

| ▸ AIMS2-Social (/10) | 8 | 5.76 | 5.47 | 0.93 | 0.47 |

| ▸ AIMS2-Work (/10) | 5 | 7.66 | 8.13 | 2.05 | 0.42 |

| Coping Efficacy (Gignac et al) | 8 | 4.08 | 4.41 | 0.46 | 0.35 |

| Clinical Disease Activity (CDAI) | 6 | 9.94 | 5.68 | 3.91 | 0.19 |

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOSSS) | 8 | 3.77 | 4.11 | 0.28 | 0.30 |

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM) | 8 | 75.80 | 73.11 | 11.75 | 0.22 |

Mentees experienced improvement in overall arthritis impact on health-related quality of life, coping and social support. Self-reported measures at programme completion (12 weeks, T2) showed significant improvements (effect size >0.3) in the overall AIMS2-SF and Social and Work subcomponents. Mentees reported improvements based on Social Support (MOSSS) and Coping Efficacy. There were no significiant effects in Disease Activity Measures Index (CDAI), Medication Adherence (Morisky) or Self-Efficacy Scale. None of these measures showed sustained improvement 3 months postprogramme (T3).

Qualitative data and process measures

The average number of meetings was 8.11 (range 6–12). The average length of meetings was 36.90 min (range 10–120 min). The mode of contact after an initial face-to-face meeting was telephone only for four dyads, with the remaining five dyads using a mix of telephone and face-to-face.

Key themes revealed from the 17 interviews are categorised below.

Mentor-specific experiences

Peer mentors largely appreciated their training; they valued the emotional support content of the training programme and being able to work through simulated scenarios. Mentors reported personally benefiting from the programme. They reported that it increased their knowledge, provided new self-management techniques and coping strategies (PM3, PM4, PM7, PM9, PM12), reinforced self-management strategies they were familiar with and made them realise how far they had come in their disease experience (PM12, PM8).

A few mentors experienced challenges (eg, mentee reluctant to stop consuming alcohol to take methotrexate (PM7); mentee with problems in returning to work after being on long-term disability (PM8)). These mentors (PM7, PM8) also experienced challenges in arranging sessions.

Mentee-specific experiences

Emotional and informational supports were most commonly reported. One mentee described his mentor as, ‘a book, as far as I'm concerned, she has more information than I can absorb, really’ (EIA8). Informational support was not confined to programme resources, but also included mentors’ experiential knowledge

‘I would ask her when she encountered bad weather, how were her joints? What did she do about that? … Can I do something prior to, when you know the weather is coming’. (EIA3)

Appraisal and instrumental support were also exchanged. One mentee said

‘It was great being able to sit down and have a normal conversation, but at the same time throw in, oh yeah, I'm thinking about switching to biologics so what's your opinion?’ (EIA1)

The inter-subjective dynamics of peer support

Participants’ experience of peer support was informed by the unique relationship they forged with their peer. Many participants spoke of having ‘a connection’ with his/her peer. This was facilitated by similarities in personality, age, gender, interests, life stage, position of responsibility at work, diagnosis, disease severity and similarity of affected joints. ‘My hands felt like her hands’, said one mentee (EIA4). Four participants faced challenges building rapport due to differences in gender, sexuality, political views and disease stage. Gender differences restricted the type of conversations in one mixed gender dyad. In another dyad, a mentee found herself disassociating from her wheelchair-bound mentor, as she was not able to cope with this

‘… I found myself looking at my mentor and going, that's not me, I don't have that, I'm not going there, I'm not going to be in a wheelchair…or be badly deformed’. (EIA6)

While such experiences complicated the work of providing and receiving peer support, all participants were unequivocal about the need for a peer support programme for individuals with EIA. Mentees spoke about the programme as ‘critical’ (EIA1), declaring, ‘It can't stop. It can't’ (EIA3). Mentors wished that similar peer support interventions had been available when they were first diagnosed.

Discussion

In this study, we piloted a peer support programme for patients with EIA using the 2008 MRC framework.17 Information from the development phase, with input from working groups and expert reviewers, and a qualitative needs assessment were used to develop a pilot peer support intervention. A complementary, inductive approach helped to make additional sense of learning and support needs, how and why the intervention met (or failed to meet) these needs and to generate information and hypotheses for testing with quantitative research methods.

A peer support programme could help patients with EIA to navigate the issues surrounding their disease. The potential advantage of peer support relates to its focus on impacts on daily activities and functioning rather than on medical information.4 Peer support encourages sharing of experiences between participants with personalised and flexible content. Our results suggested that both mentors and mentees perceived benefits from the programme. Mentors described largely positive benefits including role satisfaction, and increase in their own knowledge and self-management techniques.

Few qualitative studies to date have rigorously evaluated the effect of peer support on mentors themselves.31 Our study assessed the self-efficacy of peer mentors. Self-efficacy is the belief in one's own ability to perform well.32 While the self-efficacy scores of mentors increased after training, the scores decreased below baseline after 12 weeks of mentoring and 3 months postprogramme. This raises concerns that being a peer mentor could be a demanding and stressful experience,33 especially for mentors who expressed concerns with their mentees. The success of a peer support programme also relies on the skills and retention of peer mentors. Our preliminary results suggest that regular training and practice sessions may be necessary to maintain mentors’ self-efficacy.

Mentees showed improvements in a number of outcome measures including the Social and Work components of AIMS2-SF, Coping Efficacy and Social Support. There was a small improvement in the Affect and Symptom components of AIMS2-SF.Our study did not demonstrate a significant effect of the intervention on disease activity (CDAI), and this mirrors previous quantitative studies,34 which found no significant reduction in joint counts in RA patients who received patient–education interventions. However, the main thrust behind the study was to develop an individualised support programme that was responsive to the needs of each patient. Thus, improvements in the Coping Efficacy and Social Support scores are encouraging. The fact that improvements were not sustained 3 months postprogramme would suggest that 3 months may be insufficient for mentees to develop knowledge and skills to help them adapt to their disease. We know from the education literature that ‘booster sessions’ may be required to sustain knowledge and skill sets,35 although other studies have questioned their effectiveness.36

Our study did not demonstrate any effect on medication adherence. This reflects previous data that interventions to increase medication adherence in chronic conditions are complex, and that a large proportion of patient education interventions in this setting have been ineffective.37 A recent peer-support intervention for type 2 diabetes also yielded null results, but participants thought they would benefit from peer support early after diagnosis.33

A limitation is the small sample size. Also, there was no control group in this study. However, this study was designed as a feasibility and pilot study. The goal was to obtain initial data for planning and implementing a larger scale study. As such, results from this preliminary pilot study are not meant to be generalised. In addition, all trained mentors and mentees had RA, limiting the generalisability to other types of IA. Matching pairs based on personal and social characteristics were important, but unfortunately were unable to match all pairs by gender. The two mixed gender dyads reported that this may have limited the types of conversations they had.

In summary, this study showed that developing and delivering a peer support programme was acceptable, feasible with modifications and well received by peer mentors and mentees. Peers can be instrumental in promoting self-management and improving one's ability to cope with the diagnosis of a chronic disease. Peers also facilitate social support and may be a useful adjunct to standard rheumatological care. The information gleaned from this study has been incorporated into a randomised, wait-list controlled study comparing the ‘peer support programmes’ with a ‘standard care’ control group to further assess the benefits of peer support in EIA management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the research participants for their contribution to this study. We also recognise the important role of the other members of the research team for their contribution to this project (Emma Bell, Jennifer Boyle, Nicky Britten, Mary Cox-Dublanski, Kerry Knickle, Joyce Nyhof-Young, Laure Perrier, Susan Ross, Joan Sargeant, Ruth Tonon, Peter Tugwell, Fiona Webster).

Footnotes

Contributors: MB was the principal investigator and SS, SB and JS were the co-investigators. MB, PV, GE, SB and DR were involved in intervention development, implementation, evaluation, data analysis and manuscript writing. SS was involved in intervention development, implementation, data analysis and manuscript writing. JS was involved in intervention development, evaluation and manuscript writing. SH and AZ were involved in data analysis and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final version for publication.

Funding: This received funding from the Canadian Arthritis Network, Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Ontario Rehabilitation Research Advisory Network.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and Mount Sinai Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Tran CSJ, Nyhof-Young J, Embuldeniya G, et al. Exploring the learning and support needs of individuals with inflammatory arthritis. Univ Toronto Med J 2012;89:88–94 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakalys JA. Illness behavior in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1997;10:229–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branch VK, Lipsky K, Nieman T, et al. Positive impact of an intervention by arthritis patient educators on knowledge and satisfaction of patients in a rheumatology practice. Arthritis Care Res 1999;12:370–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doull M, O'Connor AM, Robinson V, et al. Peer support strategies for improving the health and well-being of individuals with chronic diseases (protocol). Cochrane Libr 2005;3:CD005352 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker JG, Jackson HJ, Littlejohn GO. Models of adjustment to chronic illness: using the example of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:461–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollock SE, Christian BJ, Sands D. Responses to chronic illness: analysis of psychological and physiological adaptation. Nurs Res 1990;39:300–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combe B, Landewe R, Lukas C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis: report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holbrook AM. Ontario treatment guidelines for osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and acute musculoskeletal injury. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer of Ontario, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1145–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckmann K, Strassnick K, Abell L, et al. Is a chronic disease self-management program beneficial to people affected by cancer? Aust J Prim Health 2007;13:36–44 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morisky DE, Ang A, Coly A, et al. A model HIV/AIDS risk reduction programme in the Philippines: a comprehensive community-based approach through participatory action research. Health Promot Int 2004;19:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keyserling TC, Samuel-Hodge CD, Ammerman AS, et al. A randomized trial of an intervention to improve self-care behaviors of African-American women with type 2 diabetes: impact on physical activity. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1576–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis CL. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:321–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen S, Gottlieb BH, Underwood LG. Social support measurement and intervention. In: Cohen S, Gottlieb BH, Underwood LG. eds Measuring and intervening in social support. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000:3–28 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Implementation Manual Stanford Self-Management Programs 2008 Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University, 2008. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/licensing/Implementation_Manual2008.pdf. (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Affleck G, Pfeiffer CA, Tennen H, et al. Social support and psychosocial adjustment to rheumatoid arthritis: quantitative and qualitative findings. Arthritis Rheum 1988;1:71–7 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, et al. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, et al. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986;24:67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, et al. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanford Patient Education Research Center Chronic disease self-management questionnaire codebook. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University, 2007. http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/research/cdCodeBook.pdf (accessed Aug 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, et al. AIMS2. The content and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health Status Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum 1992;35:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gignac MA, Cott C, Badley EM. Adaptation to chronic illness and disability and its relationship to perceptions of independence and dependence. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000;55:362–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aletaha D, Nell VPK, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score . Arth Res Ther 2005;7:R796–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res 2005;40:1918–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ebreo A, Feist-Price S, Siewe Y, et al. Effects of peer education on the peer educators in a school-based HIV prevention program: where should peer education research go from here? Health Educ Behav 2002;29:411–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SM, Paul G, Kelly A, et al. Peer support for patients with type 2 diabetes: cluster randomised control trial. BMJ 2011;342:d715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riemsma RP, Kirwan JR, Taal E, et al. Patient education for adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2:CD003688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taal E, Rasker JJ, Wiegman O. Group education for rheumatoid arthritis patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1997;26:805–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroese FM, Adriaanse MA, De Ridder DTD. Boosters, anyone? Exploring the added value of booster sessions in a self-management intervention. Health Educ Res 2012;27:825–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2:CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.